Socio-Demographic Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Mediating Role of Perceived Gender Discrimination Among Female Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

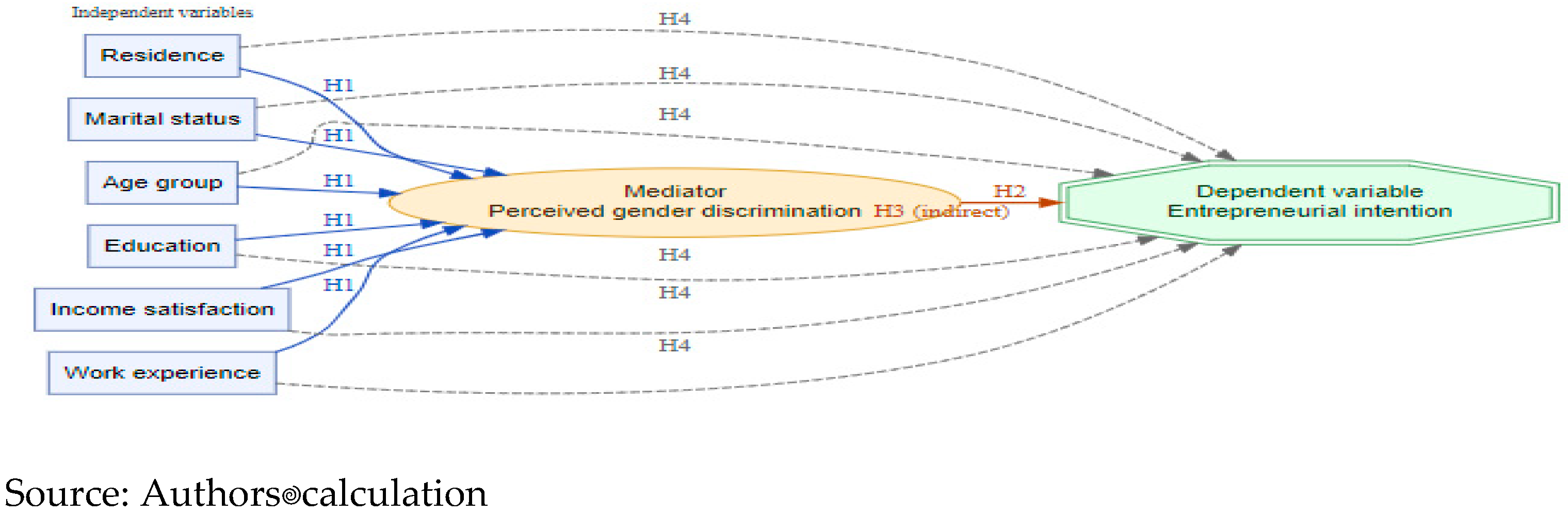

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks (TPB and Entrepreneurial Event Theory)

2.2. Gender Differences in Entrepreneurial Intention

2.3. Perceived Gender Discrimination

2.4. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intention

2.5. Research Gaps

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Approach

3.2. Population and Sampling

3.3. Mediation Model Design

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

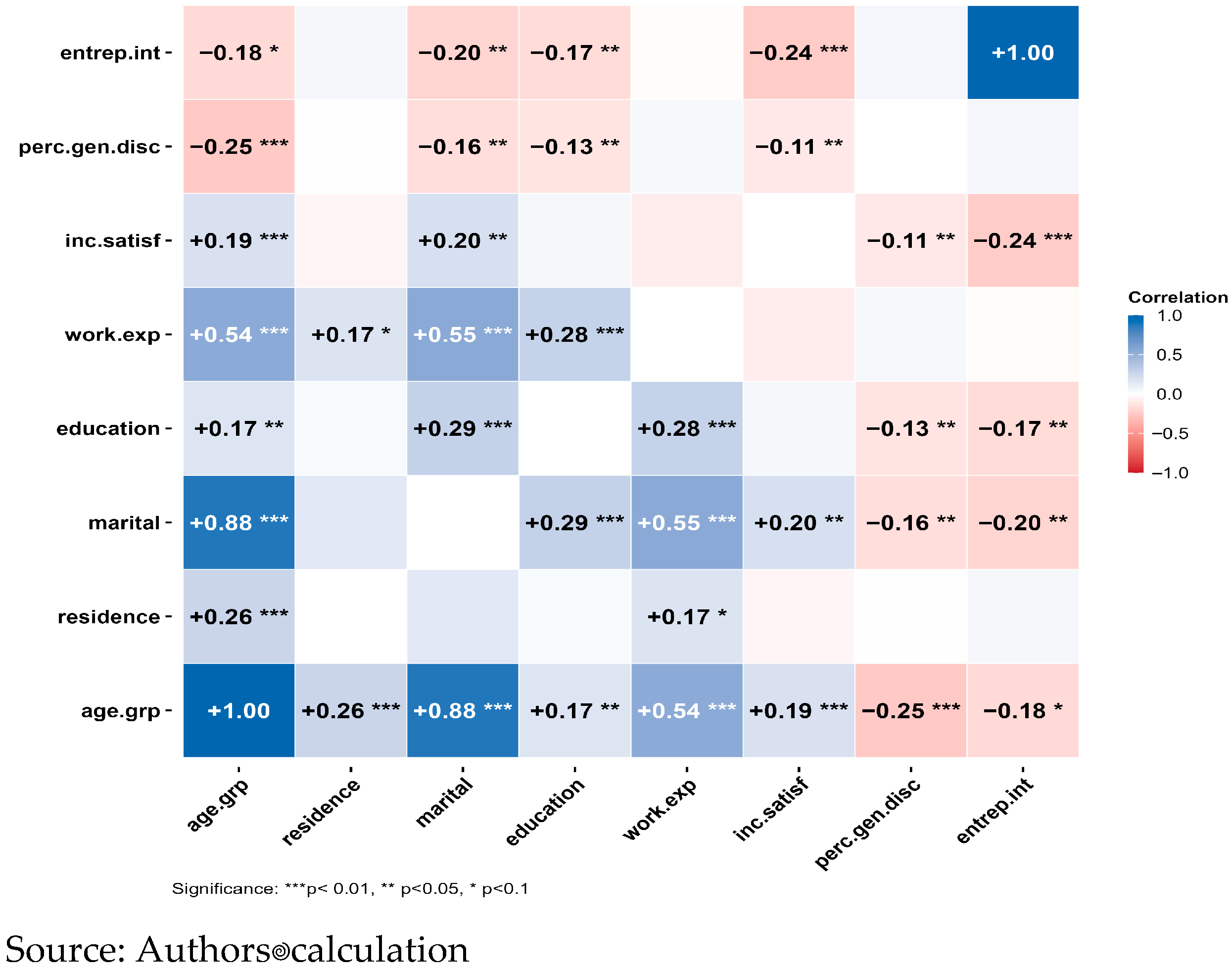

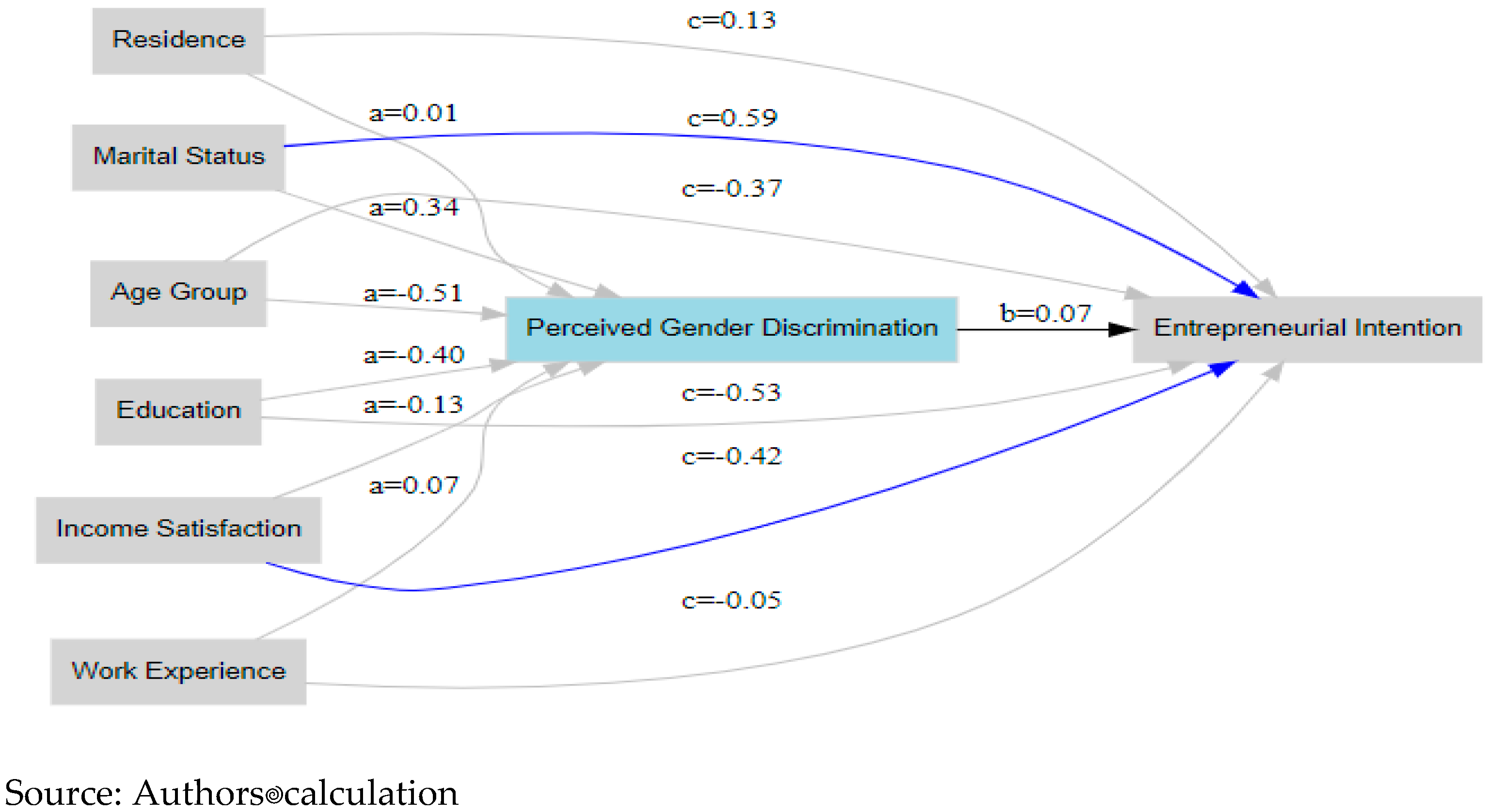

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, C.; Monfort, A.; Fornes, G.; Cardoza, G. Promoting Female Entrepreneurship: The Impact of Gender Gap Beliefs and Perceptions. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211018468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.H.B.; Kaciak, E.; Minialai, C. The influence of perceived management skills and perceived gender discrimination in launch decisions by women entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Suárez, M.; Arilla, R.; Delbello, L. The perception of effort as a driver of gender inequality: Institutional and social insights for female entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; Brush, C.G. Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 663–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguerra, N. An Investigation of Women Entrepreneurship: Motives and Barriers to Business Start Up in the Arab World. J. Women’s Entrep. Educ. 2015, 1–2, 86–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kautonen, T.; Tornikoski, E.T.; Kibler, E. Entrepreneurial intentions in the third age: The impact of perceived age norms. Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 37, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, M.; Minniti, M. The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Storey, D.J. Entrepreneurship in a regional context: Historical roots, recent developments and future challenges. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pato, M.L.; Teixeira, A.A. Twenty years of rural entrepreneurship: A bibliometric survey. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.K.; Wong, P.K. Entrepreneurial interest of university students in Singapore. Technovation 2004, 24, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaridis, I.; Kitsios, F. Gendered personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions: Insights from information technology education. Educ. Train. 2022, 64, 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, H.; Villanueva, K.; Eidelman, L.; Szwykowski, O. Educational level as a protective factor against perceived discrimination in Europe: Evidence from the European Social Survey (Round 10). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sinha, E.; Shalender, K. Espoused model of women entrepreneurship: Antecedents to women entrepreneurial intention and moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. J. Enterp. Commun. 2023, 18, 881–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023/24 Women’s Entrepreneurship Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=51601 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; Kent, C., Sexton, D., Vesper, K., Eds.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr. The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2000, 24, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Xie, R.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Subramaniam, N.; Nair, V.K.; Shivdas, A.; Achuthan, K.; Nedungadi, P. Women Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development: Bibliometric Analysis and Emerging Research Trends. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A.; Boghean, C.; Boghean, F. The role of entrepreneurship in enhancing economic development: The mediating role of gender and motivations. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2025, 26, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Marques, C.S.; Ferreira, J.J. The Impact of Gender on Entrepreneurial Intention in a Peripheral Region of Europe: A Multigroup Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Giacomin, O.; Janssen, F. Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions: The role of gender and culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, A.B.; Brush, C.G.; Greene, P.G.; Baumer, B.; Dean, M.; Heavlow, R. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Women’s Entrepreneurship Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.babson.edu/media/babson/assets/global-entrepreneurship-monitor/GEM-2018-2019-Womens-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mahfud, T.; Triyono, M.B.; Sudira, P.; Mulyani, Y. Structural Equation Modeling-Based Multi-Group Analysis: Examining the Role of Gender in the Link between Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurial Intention. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández Sánchez, B.R.; de Miranda Justo, J.M.R.; Sánchez García, J.C. Understanding social entrepreneurial intention in higher education: Does gender and type of study matter? Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 49, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.D.; Bui, L.P.; Vu, P.A.; Dang-Van, T.; Le, B.N.; Nguyen, N. Understanding female students’ entrepreneurial intentions: Gender inequality perception as a barrier and perceived family support as a moderator. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 17, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.W.; Mustafa, M.J.; Nungsari, M. Subjective norms towards entrepreneurship and Malaysian students’ entrepreneurial intentions: Does gender matter? Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 18, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.P.; Arena, D.F.; Nittrouer, C.L.; Alonso, N.M.; Lindsey, A.P. Subtle Discrimination in the Workplace: A Vicious Cycle. Ind. Org. Psych. 2017, 10, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S.; Swail, J. Gender, risk and finance: Why can’t a woman be more like a man? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.Y.; Yeasmin, A.; Ahmed, Z. Perception of women entrepreneurs to accessing bank credit. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; McDougald, M.S. Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M.J. Perceived barriers influencing the formation of entrepreneurial intention. J. Cont. Manag. 2015, 12, 881–905. [Google Scholar]

- Antohi, I.; Ghiță-Mitrescu, S. NEET’s Attitude Towards Entrepreneurship. “Ovidius” Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2022, 22, 498–506. [Google Scholar]

- Minniti, M.; Naudé, W. What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2010, 22, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.; Vorley, T. Institutional asymmetry: How formal and informal institutions affect entrepreneurship in Bulgaria. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 33, 840–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.; Dragusin, M. Women-entrepreneurs: A dynamic force of small business sector. Amfiteatru Econ. 2006, 20, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiță-Mitrescu, S.; Antohi, I. NEETs’ Perception on Financing an Entrepreneurial Endeavour. “Ovidius” Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2023, 23, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, A.D.; Duhnea, C. Customer orientation in the marketing activity of Romanian companies. Manag. Strat. J. 2014, 26, 698–703. [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen, M. Exploring alternative approaches in high-level entrepreneurship education: Creating micro-mechanisms for endogenous regional growth. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2000, 12, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Walmsley, A.; Liñán, F.; Akhtar, I.; Neame, C. Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, J. The effect of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of different college students: Gender, household registration, school type, and poverty status. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.; Cliff, J. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, I.; Thurik, R.; Grilo, I.; Van der Zwan, P. Explaining preferences and actual involvement in self-employment: Gender and the entrepreneurial personality. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.C.; Gimeno-Gascon, F.J.; Woo, C.Y. Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Grilli, L. Founders’ human capital and the growth of new technology-based firms: A competence-based view. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M.M.; Zacher, H.; Wang, M. Age in the entrepreneurial process: The role of future time perspective and prior entrepreneurial experience. J. Appl. Psych. 2018, 103, 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, B.; Boudreaux, C.J.; Palich, L. Cross-country determinants of early-stage necessity and opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship: Accounting for model uncertainty. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 243–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 155–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. Disadvantage and discrimination in self-employment and entrepreneurship. In Handbook on Economics of Discrimination and Affirmative Action; Deshpande, A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 267–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 156–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 178–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 45–78. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.D.; Bosma, N.; Autio, E.; Hunt, S.; De Bono, N.; Servais, I.; Lopez-Garcia, P.; Chin, N. Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Turban, D.B.; Wasti, S.A.; Sikdar, A. The Role of Gender Stereotypes in Perceptions of Entrepreneurs and Intentions to Become an Entrepreneur. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.M.; Shahzad, M.F.; Xu, S. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention to initiate new ventures: Evidence from university students. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gibb, L.C.; Nielsen, K. Entrepreneurship Within Urban and Rural Areas: Creative People and Social Networks. Reg. Std. 2013, 48, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Ploj, G. Job Stability, Earnings Dynamics, and Life-Cycle Savings; IZA DP No. 13887; Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamvada, J.P.; Shrivastava, M.; Mishra, T.K. Education, social identity and self-employment over time: Evidence from a developing country. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 59, 1449–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Fisch, C.O.; van Praag, M. The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: A review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Ind. Innov. 2016, 24, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, A.M.; Omair, K. Males’ Attitudes towards Working Females in Saudi Arabia. Pers. Rev. 2010, 39, 746–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücetas, H.; Carol, S. The influence of education on gender attitudes among ethno-religious majority and minority youth in Germany from a longitudinal perspective. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Kimmitt, J.; Kibler, E.; Farny, S. Living on the slopes: Entrepreneurial preparedness in a context under continuous threat. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 31, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, D.; Cockalo, D.; Bogetic, S.; Bakator, M. Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions among the Youth in Serbia with a Classification Decision Tree Model with the QUEST Algorithm. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virasa, T.; Sukavejworakit, K.; Promsiri, T. Predicting Entrepreneurial Intention and Economic Development: A Cross-National Study of its Policy Implications for Six ASEAN Economies. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniyi, A.O. The mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, T.S.T.; Hashim, N.; Zakaria, N. Entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial success: The mediating role of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition and innovation capability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarría, D.M.; Ingram, A.E. Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions and gendered national-level entrepreneurial activity: A 14-year panel study of GEM. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.J.; Roomi, M.A.; Liñán, F. About gender differences and the social environment in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S.A.; Lloyd, A. The 2015 Female Entrepreneurship Index. Kelley School of Business Research Paper No. 15-51. 2015. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2625254 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Esteves, J.; de Haro Rodríguez, G.; Ballestar, M.T.; Sainz, J. Gender and generational cohort impact on entrepreneurs’ emotional intelligence and transformational leadership. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 20, 1295–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifle, A.M.; Jamaludin, N.; Md Zulkifli, N.F.; Yunus, N.M.; Idris, K.; Ahmad, N. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurship Intention: A Longitudinal Study among Youth in Higher Learning Institutions. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Kautonen, T.; Fink, M. From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self-control and action-related doubt, fear, and aversion. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G.; Tsukanova, T.; Morris, M.H. The Moderating Role of National Culture in the Relationship Between University Entrepreneurship Offerings and Student Start-Up Activity: An Embeddedness Perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criaco, G.; Sieger, P.; Wennberg, K.; Chirico, F.; Minola, T. Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword” for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, S.; Deakins, D.; Whittam, G. The measurement of social capital in the entrepreneurial context. J. Enterp. Commun. 2009, 3, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tekreeti, T.; Al Khasawneh, M.; Dandis, A.O. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions among students in higher education institutions. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2024, 38, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, T.; Alvarez, C.; Urbano, D. Understanding institutional dimensions in high-impact female entrepreneurship. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gorgievski, M.J.; Qi, J.; Paas, F. Perceived university support and entrepreneurial intentions: Do different students benefit differently? Stud Edu. Eval. 2022, 73, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, D.; Chinta, R. Unveiling the Power of Race and Education in Shaping Entrepreneurial Dreams: An Empirical Study in Florida. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, A.; Muhammad, A.N.; Muhammad, A.R. Exploring the intersectionality of ethnicity, gender and entrepreneurship: A case study of Nepali women in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Gen. Entrep. 2025, 17, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owalla, B.; Nyanzu, E.; Vorley, T. Intersections of gender, ethnicity, place and innovation: Mapping the diversity of women-led SMEs in the United Kingdom. Int. Small Bus. J. 2021, 39, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Javed, H.; Sun, L.; Abbas, M. Influence of entrepreneurship support programs on nascent entrepreneurial intention among university students in China. Front. Psych. 2022, 13, 955591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozward, D.; Rogers-Draycott, M.; Angba, C.; Zhang, C.; Ma, H.; An, F.; Topolansky, F.; Sabia, L.; Bell, R.; Beaumont, E. How can entrepreneurial interventions in a university context impact the entrepreneurial intention of their students? Entrep. Educ. 2023, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Count | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age.grp | 360 | 18–25 years | 294 | 81.67 |

| 26–30 years | 16 | 4.44 | ||

| 31–35 years | 10 | 2.78 | ||

| 36–40 years | 24 | 6.67 | ||

| Over 40 years | 16 | 4.44 | ||

| residence | 360 | rural | 111 | 30.83 |

| urban | 249 | 69.17 | ||

| marital | 360 | not married | 304 | 84.44 |

| married | 56 | 15.56 | ||

| education | 360 | 1st year bachelor | 62 | 17.22 |

| 2nd year bachelor | 95 | 26.39 | ||

| 3rd year bachelor | 142 | 39.44 | ||

| 1st year master | 28 | 7.78 | ||

| 2nd year master | 33 | 9.17 | ||

| wrk.exp | 360 | no | 85 | 23.61 |

| yes | 275 | 76.69 | ||

| entrep.int | 360 | I haven’t decided | 113 | 31.39 |

| I want to do it | 247 | 68.69 |

| Variable | Count | Min | Max | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inc.satisf | 360 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| perc.gen.disc | 360 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Variable | Df | GVIF | GVIF_adj | VIF_like | Tolerance_like | Flag_VIFgt5 | Flag_VIFgt10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age.grp | 4 | 2.570454533 | 1.12525575 | 1.266200503 | 0.789764337 | FALSE | FALSE |

| residence | 1 | 1.044459585 | 1.021988055 | 1.044459585 | 0.957432929 | FALSE | FALSE |

| marital | 1 | 2.329887593 | 1.526396932 | 2.329887593 | 0.429205256 | FALSE | FALSE |

| education | 4 | 1.158048617 | 1.018511294 | 1.037365255 | 0.963980618 | FALSE | FALSE |

| work.exp | 1 | 1.139615487 | 1.067527745 | 1.139615487 | 0.877488952 | FALSE | FALSE |

| inc.satisf | 1 | 1.072311457 | 1.035524726 | 1.072311457 | 0.932564875 | FALSE | FALSE |

| perc.gen.disc | 1 | 1.082273448 | 1.040323723 | 1.082273448 | 0.923980905 | FALSE | FALSE |

| Independent Variable (IV) | Direct Effect | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age.grp | −0.3692 | −1.4413 | 0.8503 | 0.2299 | |

| residence | 0.1294 | −0.3540 | 0.6040 | 0.5966 | |

| marital | 0.5943 | 0.0030 | 1.1760 | 0.0489 | * |

| education | −0.5260 | −1.3790 | 0.3155 | 0.0837 | . |

| work.exp | −0.0489 | −0.5871 | 0.4698 | 0.8554 | |

| inc.satisf | −0.4209 | −0.6709 | −0.1806 | 0.0005 | *** |

| Independent Variable (IV) | a-Path | b-Path | Indirect Effect | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age.grp | −0.5112 | 0.0405 | −0.0041 | −0.0327 | 0.0175 | 0.680 | |

| residence | 0.0111 | 0.0726 | 0.0002 | −0.0069 | 0.0085 | 0.986 | |

| marital | 0.3369 | 0.0542 | 0.0045 | −0.0122 | 0.0229 | 0.562 | |

| education | −0.4045 | 0.0450 | −0.0026 | −0.0215 | 0.0104 | 0.690 | |

| work.exp | 0.0680 | 0.0733 | 0.0011 | −0.0064 | 0.0101 | 0.806 | |

| inc.satisf | −0.1319 | 0.0374 | −0.0005 | −0.0041 | 0.0025 | 0.672 |

| Independent Variable (IV) | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age.grp | −0.3692 | −0.0372 | −0.4064 | −1.5842 | 0.9188 | 0.2299 | |

| residence | 0.1294 | 0.0008 | 0.1302 | −0.3726 | 0.6242 | 0.5966 | |

| marital | 0.5943 | 0.0245 | 0.6189 | −0.0404 | 1.2685 | 0.0489 | * |

| education | −0.5260 | −0.0295 | −0.5554 | −1.4910 | 0.3686 | 0.0837 | . |

| work.exp | −0.0489 | 0.0050 | −0.0440 | −0.6067 | 0.4993 | 0.8554 | |

| inc.satisf | −0.4209 | −0.0096 | −0.4305 | −0.7070 | −0.1637 | 0.0005 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antohi, I.; Ghita-Mitrescu, S.; Moraru, A.-D.; Duhnea, C.; Ilie, M.; Schipor, G.-L. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Mediating Role of Perceived Gender Discrimination Among Female Students. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209181

Antohi I, Ghita-Mitrescu S, Moraru A-D, Duhnea C, Ilie M, Schipor G-L. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Mediating Role of Perceived Gender Discrimination Among Female Students. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209181

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntohi, Ionut, Silvia Ghita-Mitrescu, Andreea-Daniela Moraru, Cristina Duhnea, Margareta Ilie, and Georgiana-Loredana Schipor. 2025. "Socio-Demographic Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Mediating Role of Perceived Gender Discrimination Among Female Students" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209181

APA StyleAntohi, I., Ghita-Mitrescu, S., Moraru, A.-D., Duhnea, C., Ilie, M., & Schipor, G.-L. (2025). Socio-Demographic Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Mediating Role of Perceived Gender Discrimination Among Female Students. Sustainability, 17(20), 9181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209181