From Productivity to Sustainability?: Formal Institutional Changes and Perceptual Shifts in Japanese Corporate HRM

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Aim

- RQ1: How has the overall perception of HRM in Japanese companies evolved in response to a series of top-down institutional reforms between 2008 and 2024?

- RQ2: How has the use of the terms WLB, WS, and HC changed in frequency and meaning over time?

1.2. Context of Japan

2. Literature Review

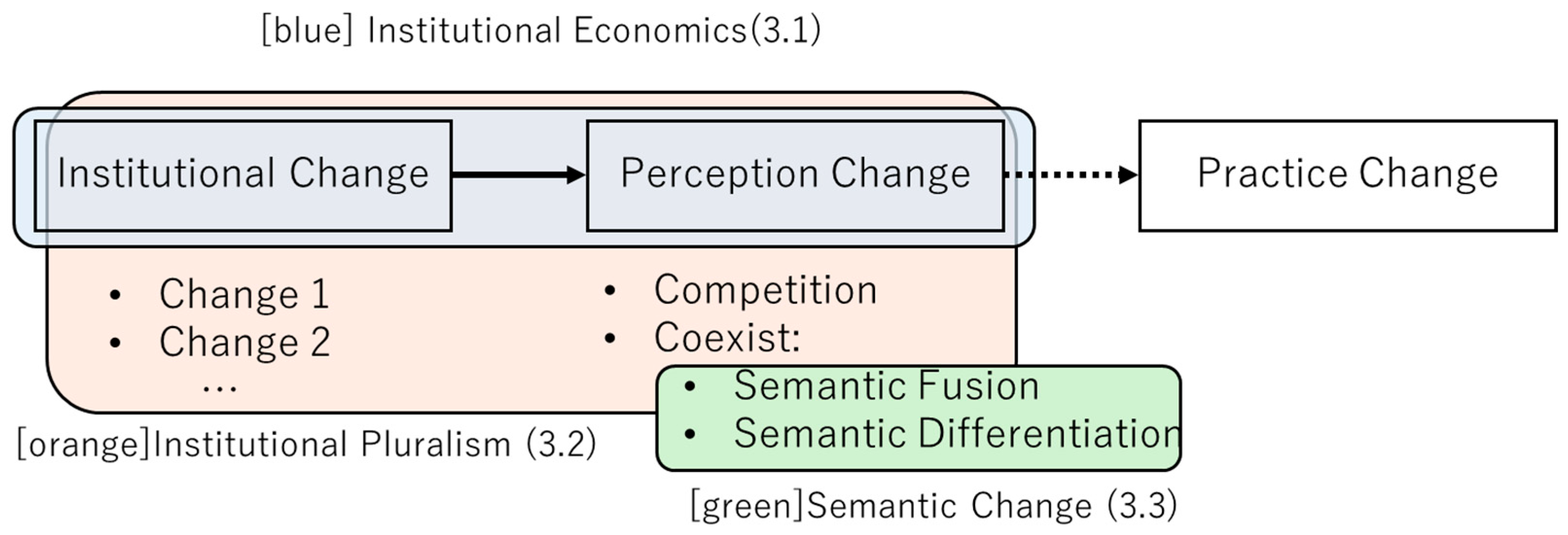

2.1. Institutional Change and Perception (Institutional Economics)

2.2. Institutional Pluralism

2.3. Coexistence, Competition, and Semantic Change

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Procedures

3.3. Analysis

3.3.1. RQ1: Overall HRM Trends

- (1)

- current snapshot of perceptions.

- (2)

- centrality of specific industries.

- (3)

- temporal changes over time.

- 2008–2017: From the charter of WLB announcement to the implementation of the WS Reform.

- 2018–2019: From the implementation of the WS Reform to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 2020–2022: From the COVID-19 pandemic to the introduction of the HC disclosure.

- 2023–2024: After the HC disclosure mandate.

3.3.2. RQ2: Relationships Between the Three Terms

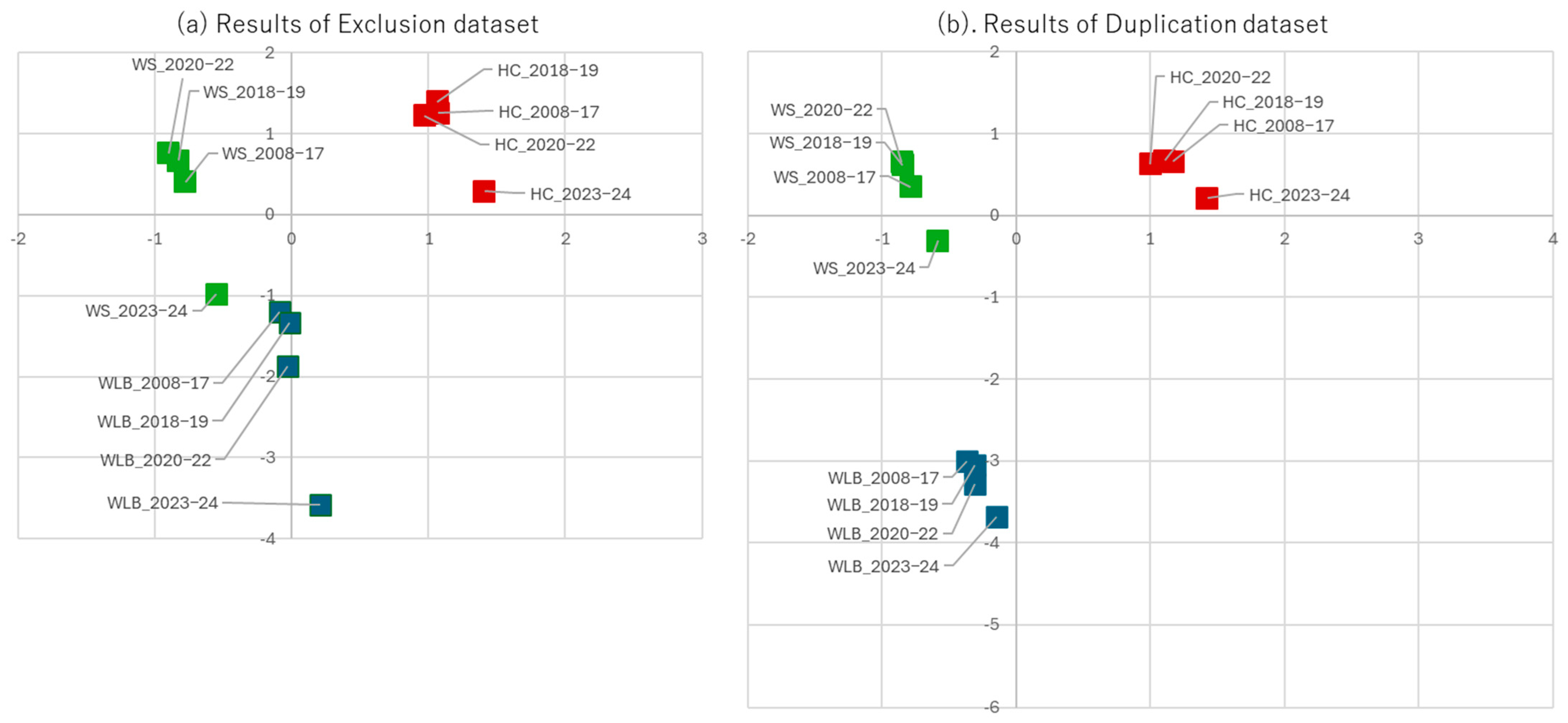

- Exclusion dataset: documents containing overlapping concepts were removed.

- Duplication dataset: documents containing multiple keywords were duplicated.

4. Results

4.1. Overall HRM Trends (RQ1)

4.2. Relationships Between the Three Terms (RQ2)

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

5.2. Political, Economic, and Cultural Background of Semantic Shifts

5.3. Sectoral Structure and Interpretation

6. Conclusions, Implications and Future Works

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

6.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HC | Human Capital |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| MD&A | Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations |

| METI | Ministry Of Economy, Trade and Industry |

| ND | Narrative Disclosures |

| OECD | Organization For Economic Co-Operation and Development |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| T&IC | Transportation and Information and Communications Industry |

| TSE | Tokyo Stock Exchange |

| WS | Work Style |

Appendix A. Parameters Used in Text Analysis

| Before | After | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| (株) | 株式会社 | Ltd. Or |

| employee | 従業員 | employee |

| human capital | 人的資本 | human capital |

| human resouce | 人的資源 | human resource |

| management | 経営 | management |

| officer | 取締役 | officer |

| WLB | ワークライフバランス | WLB |

| worklife | ワークライフ | worklife |

| 企業 | 会社 | company |

| サステナビリティ | 持続可能性 | sustainability |

| 事業 | ビジネス | business |

| 仕事と生活 | ワークライフ | work life |

| 社員 | 従業員 | employee |

| 人財 | 人材 | workforce |

| ダイバーシティ | 多様性 | diversity |

| 取組 | 取り組 | working on |

| ヒューマンキャピタル | 人的資本 | human capital |

| ヒューマンリソース | 人的資源 | human resource |

| マテリアリティ | 重要課題 | materiality |

| マネジメント | 経営 | management |

| 役員 | 取締役 | director |

| ワークスタイル | 働き方 | work style |

| Category | Japanese Words | English Words |

|---|---|---|

| Forced Extraction | 従業員 | employee |

| 働き方 | work style | |

| 持続可能性 | sustanability | |

| 持続可能 | sustanable | |

| 人的資本 | human capital | |

| 人的資源 | human resource | |

| ワークライフ | work life | |

| 可能性 | possibiity | |

| 生産性 | productivity | |

| 多様性 | diversity | |

| 重要課題 | materiality | |

| 福利厚生 | welfare | |

| Stop-words | 年度 | fiscal year |

| 平成 | Heisei | |

| 月 | month | |

| 昭和 | Sho-wa |

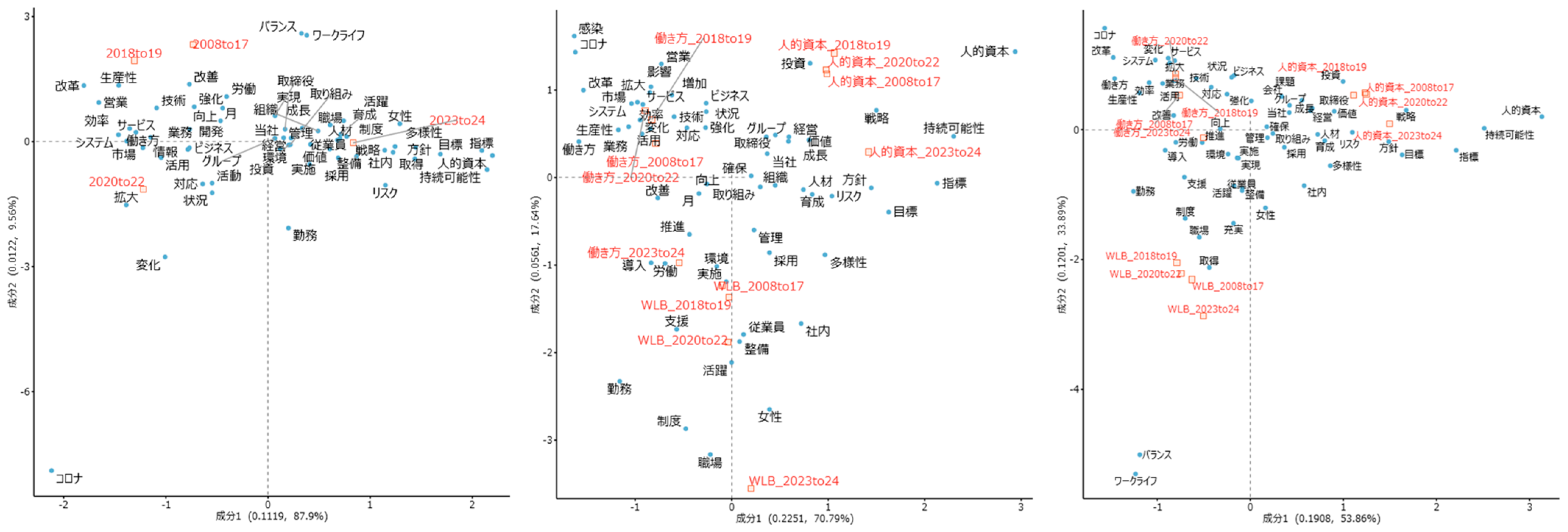

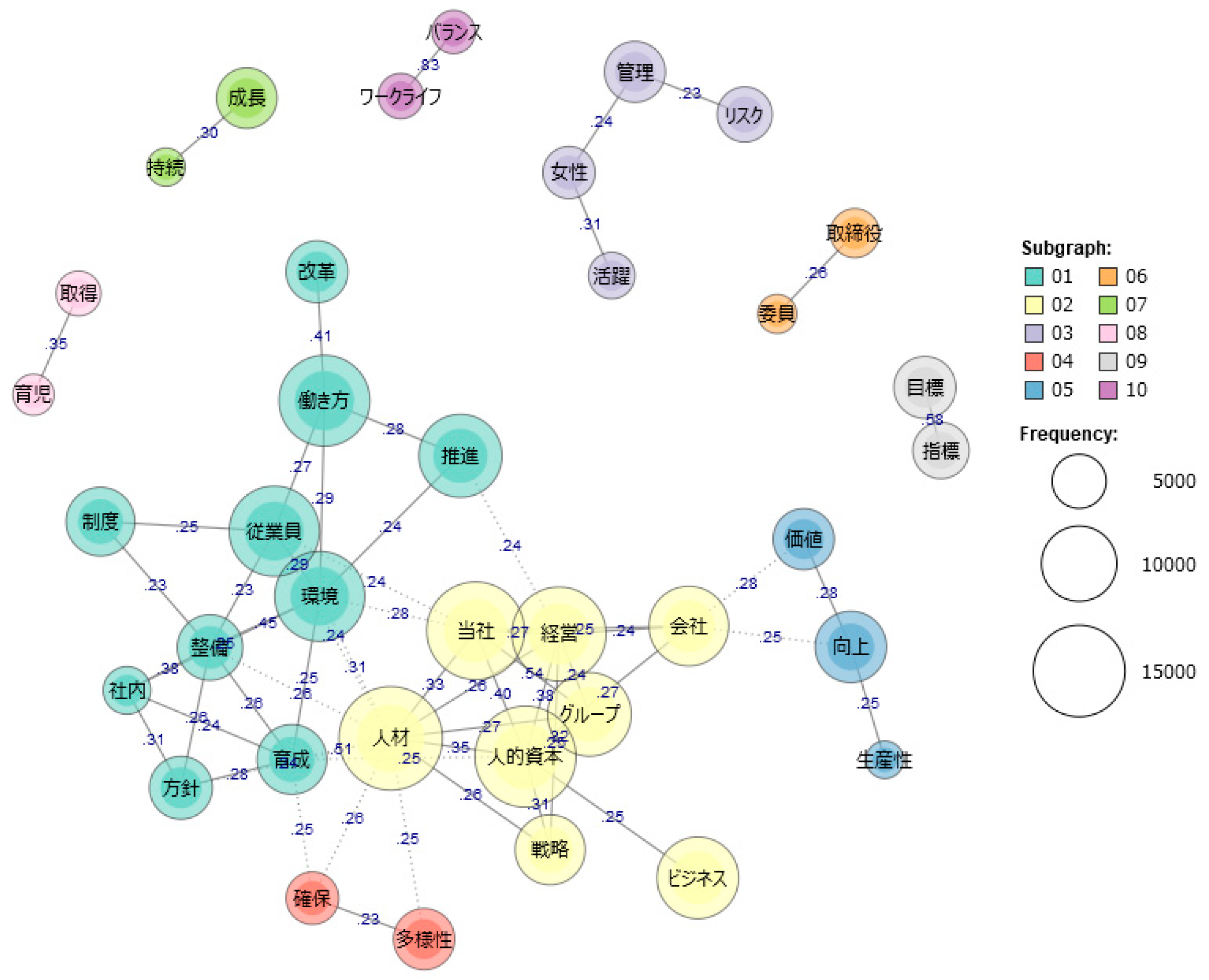

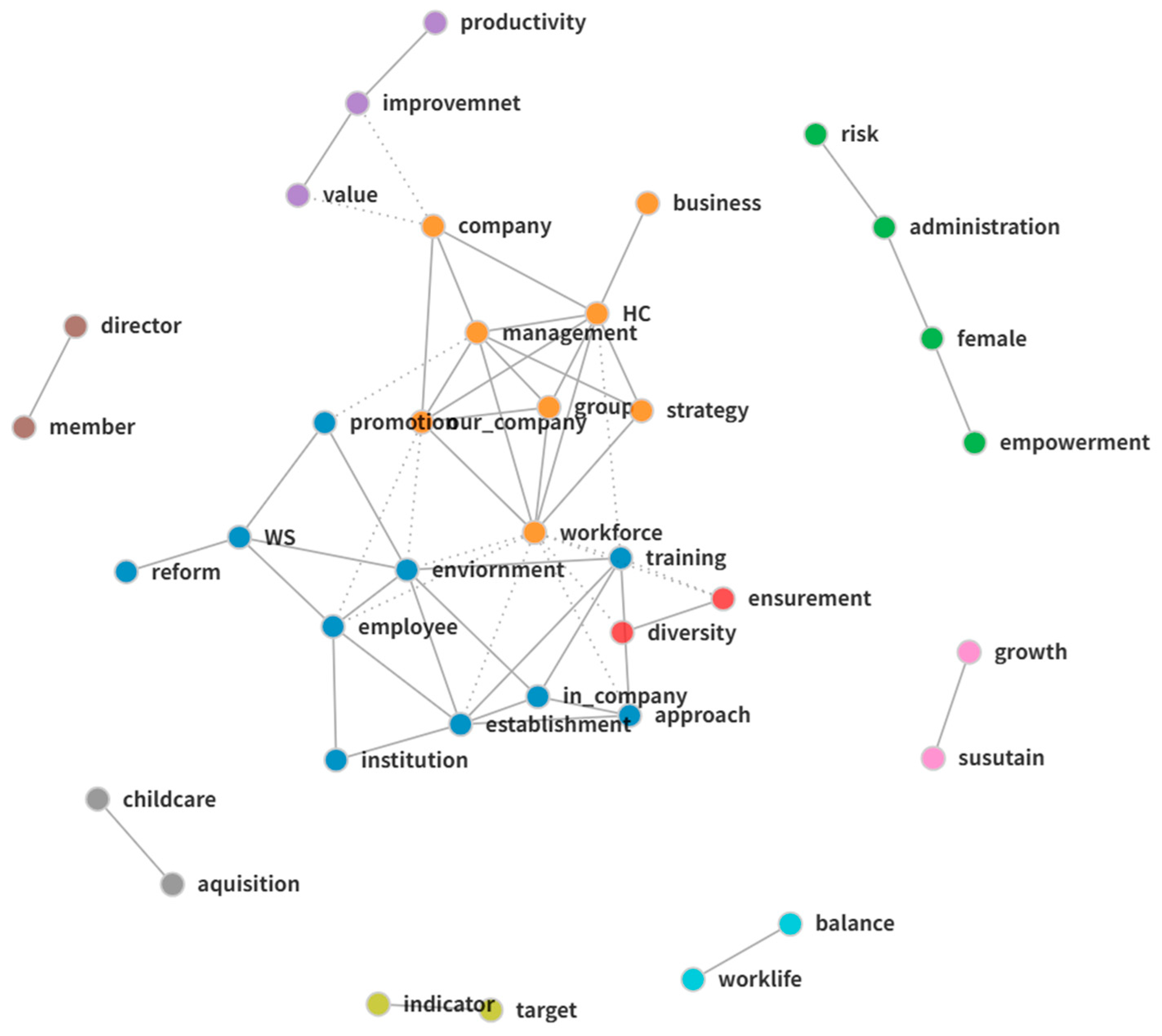

| Figure 2 | Figure 4 | Figure 6a | Figure 6b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| method | Co-occurrence | Correspondene | Correspondene | Correspondene |

| period | 2023−2024 | 2008−2024 | 2008−2024 | 2008−2024 |

| Duplicate Handling | remove | dupulicate | ||

| Number of Words Used | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Number of Candidate Words | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| Frequency Bar | 2200 | 4200 | 3800 | 4200 |

| Horizontal Axis (in the case of correspondence analysis) | 84.11% | 70.56% | 56.19% | |

| Vertical Axis (in the case of correspondence analysis) | 13.48% | 17.87% | 31.02% |

Appendix B. Analytical Procedures

Appendix B.1

| for Figure 4 | ||||||

| axis | direction | distinctive words | ||||

| Holizontal | right | infection | COVID | reform | sales | system |

| left | direction | target | indicator | sustainability | HC | |

| Vertical | upper | improvement | productivity | reform | work-life | balance |

| lower | infection | COVID | work(katakana) | change | work | |

| for Figure 6a | ||||||

| axis | direction | distinctive words | ||||

| Holizontal | right | HC | sustainability | indicator | target | strategy |

| left | efficiency | work | productivity | reform | WS | |

| Vertical | upper | expansion | reform | effect | sales | investment |

| lower | workplace | institusion | female | work | contribution | |

| for Figure 6b | ||||||

| axis | direction | distinctive words | ||||

| Holizontal | right | HC | strategy | direction | risk | diversity |

| left | WS | reform | work | productivity | efficiency | |

| Vertical | upper | reform | WS | investment | change | system |

| lower | work-life | balance | acquisition | workplace | female | |

Appendix B.2

Appendix C. Additional Analysis (Labels in Japanese)

| Japanese | English | Japanese | English | Japanese | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| グループ | group | 環境 | environment | 状況 | situation |

| コロナ | COVID | 管理 | administration | 職場 | workplace |

| サービス | service | 技術 | technology | 人材 | workforce |

| システム | system | 強化 | reinforcement | 人的資本 | HC |

| バランス | balance | 業務 | operation | 推進 | advancement |

| ビジネス | business | 勤務 | work | 制度 | institution |

| リスク | risk | 経営 | management | 成長 | growth |

| ワーク | work(katakana) | 月 | month | 整備 | establishment |

| ワークライフ | work-life | 効率 | efficiency | 生産性 | productivity |

| 委員 | member | 向上 | enhancement | 戦略 | strategy |

| 育児 | childcare | 採用 | recruitment | 組織 | organization |

| 育成 | training | 市場 | market | 増加 | increase |

| 営業 | sales | 指標 | indicator | 多様性 | diversity |

| 影響 | effect | 支援 | support | 対応 | handle |

| 価値 | value | 持続 | sustain | 投資 | investment |

| 課題 | challenge | 持続可能性 | sustainability | 当社 | our_company |

| 会社 | company | 実現 | realization | 働き方 | WS |

| 改革 | reform | 実施 | implementation | 導入 | introduction |

| 改善 | improvement | 社内 | in_company | 年度 | fiscal year |

| 開発 | development | 取り組み | action | 平成 | Heisei |

| 拡大 | expansion | 取締役 | director | 変化 | change |

| 確保 | ensurement | 取得 | acquisition | 方針 | direction |

| 活動 | activity | 従業員 | employee | 目標 | target |

| 活躍 | contribution | 女性 | female | 労働 | labor |

| 活用 | utilization | 昭和 | Sho-wa | ||

| 感染 | infection | 情報 | information |

References

- Healy, T.; Cote, S. The Well-Being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital. Education and Skills; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Political Econ. 1962, 70 Pt 2, 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marrewijk, M.; Timmers, J. Human Capital Management: New Possibilities in People Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzina, Y.; Firsova, I.; Strielkowski, W. Dynamics of Human Capital Development in Economic Development Cycles. Economies 2021, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharčíková, A.; Mičiak, M.; Tokarčíková, E.; Štaffenová, N. The Investments in Human Capital within the Human Capital Management and the Impact on the Enterprise’s Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozza, C.; Divella, M. Human Capital and Firms’ Innovation: Evidence from Emerging Economies. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2019, 28, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovbetov, I. Does Employee Happiness Create Value for Firm Performance? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 30414:2018; Human Resource Management—Guidelines for Internal and External Human Capital Reporting. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:30414:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Georgiev, G.S. The Human Capital Management Movement in U.S. Corporate Law. Tul. L Rev. 2020, 95, 639. [Google Scholar]

- Vithana, K.; Jayasekera, R.; Choudhry, T.; Baruch, Y. Human Capital Resource as Cost or Investment: A Market-Based Analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 1213–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFRAG Sustainability Reporting|EFRAG. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/en/sustainability-reporting (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Brewster, C. Comparative HRM: European Views and Perspectives. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Malina, D.; Yuan, L. How Culture-Sensitive Is HRM? A Comparative Analysis of Practice in Chinese and UK Companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1995, 6, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONRAD, H. From Seniority to Performance Principle: The Evolution of Pay Practices in Japanese Firms since the 1990s. Soc. Sci. Jpn. J. 2010, 13, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-K.; Shivdasani, A. Corporate Restructuring during Performance Declines in Japan. J. Financ. Econ. 1997, 46, 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Kodama, N.; Arita, K.; Kazama, H.; Sakai, S.; Takeuchi, M.; Owan, H. Has Japan’s Work Style Reform Had the Intended Effect? Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 2757–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegglen, J.G. The Japanese Factory: Aspects of Its Social Organization; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1958; p. xiii142. [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi, C. Japanese-Style Human Resource Management and Its Historical Origins. Jpn. Labor Rev. 2014, 11, 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Iyoda, M. Postwar Japanese Economy: Lessons of Economic Growth and the Bubble Economy; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4419-6332-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmberg, D. From Advantage to Handicap: Traditional Japanese HRM and the Case for Change. Organ. Dyn. 2014, 43, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office Website Promoting Work-Life Balance. Available online: https://wwwa.cao.go.jp/wlb/government/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Hirokawa, S. The Psychological Impact of Job Loss in Japan after the “Lehman Shock”. Jpn. Labor Rev. 2012, 9, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.L.; Ogawa, N.; Kondo, M.; Matsukura, R. Population Decline, Labor Force Stability, and the Future of the Japanese Economy. Eur. J. Popul. 2010, 26, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venne, R.A. Population Aging in Canada and Japan: Implications for Labour Force and Career Patterns. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. L’adm. 2001, 18, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; North, S.; Weathers, C. Abe Shinzō’s Campaign to Reform the Japanese Way of Work. Asia-Pac. J. 2017, 15, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, G.; Kambayashi, R.; Kato, T. The Impact of Overtime Limits on Firms and Workers: Evidence from Japan? S Work Style Reform; IZA-Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- RIETI-Outlook on the 2024 Problem: Seizing the Chance to Change the Low-Pricing Model. Available online: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/papers/contribution/kuroda-sachiko/03.html (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Study Group on Sustainable Corporate Value Enhancement and Human Capital. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/economy/improving_corporate_value/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Study Group for Realizing Human Capital Management. Available online: https://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/14455765/www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/economy/jinteki_shihon/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Cabinet Office New Capitalism Realization Headquarters/New Capitalism Realization Conference. Available online: https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/atarashii_sihonsyugi/wgkaisai/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Japan Exchange Group, Inc. Enhancing Corporate Governance. Available online: https://www.jpx.co.jp/english/equities/listing/cg/index.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0-521-39734-6. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Understanding the Process of Economic Change; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4008-2948-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kraatz, M.S.; Block, E.S. Organizational Implications of Institutional Pluralism. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2008; pp. 243–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Raynard, M.; Kodeih, F.; Micelotta, E.R.; Lounsbury, M. Institutional Complexity and Organizational Responses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 317–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-19-960193-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ullmann, S. Semantics: An Introduction to the Science of Meaning; Oxford B. Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, A.; Koch, P. Historical Semantics and Cognition; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1999; ISBN 978-3-11-016614-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7432-5823-4. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson, E. Management Fashion. AMR 1996, 21, 254–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, J.; Nijholt, J.; Heusinkveld, S. Using Print Media Indicators in Management Fashion Research. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røvik, K.A. From Fashion to Virus: An Alternative Theory of Organizations’ Handling of Management Ideas. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.-B.; Shen, Y.K.; Aiden, A.P.; Veres, A.; Gray, M.K.; The Google Books Team; Pickett, J.P.; Hoiberg, D.; Clancy, D.; Norvig, P.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science 2011, 331, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Potter, G.; Srinivasan, D. An Empirical Investigation of an Incentive Plan That Includes Nonfinancial Performance Measures. Account. Rev. 2000, 75, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Pham, V.T. COVID-19 Disclosures and Market Uncertainty: Evidence from 10-Q Filings. Aust. Account. Rev. 2022, 32, 238–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Rudžionienė, K. Corporate COVID-19-Related Risk Disclosure in the Electricity Sector: Evidence of Public Companies from Central and Eastern Europe. Energies 2022, 15, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macanovic, A. Text Mining for Social Science—The State and the Future of Computational Text Analysis in Sociology. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 108, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I-N Information Systems, Ltd. Company Information. Available online: https://www.indb.co.jp/corporate/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Higuchi, K. KH Coder 3 Reference Manual; Ritsumeikan University: Kyoto, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yano, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Ishitsuka, S.; Maruyama, A. Consumer Attitudes toward Vertically Farmed Produce in Russia: A Study Using Ordered Logit and Co-Occurrence Network Analysis. Foods 2021, 10, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M. Correspondence Analysis in Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, H. Why Do the Japanese Work Long Hours? Jpn. Labor Issues 2018, 2, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, R.; Piontek, T.; Metrick, A. The Lehman Brothers Bankruptcy A: Overview. J. Financ. Cris. 2019, 1, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.; Chai, D.H.; Deakin, S. Unexpected Corporate Outcomes from Hedge Fund Activism in Japan. Socioecon. Rev. 2020, 18, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, L.S.; Henry, M. Integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into Corporate Governance: A Cross-Sectoral Analysis of Japanese Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry White Paper on Manufacturing 2025 (Annual Report Based on Article 8 of the Basic Act on the Promotion of Core Manufacturing Technology). Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/report/whitepaper/mono/2025/index.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Elamer, A.A.; Kato, M. Governance Dynamics and the Human Capital Disclosure-Engagement Paradox: A Japanese Perspective. Compet. Rev. 2024, 35, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitani, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Nakai, T. Text Mining Analysis of Human Capital Information Disclosure in a Corporate Governance Report. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of JSAI, Hamamatsu, Japan, 28–31 May 2024; Volume JSAI2024, p. 2I6GS1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, A.; Fiori, S. Ideologies and Beliefs in Douglass North’s Theory. Eur. J. Hist. Econ. Thought 2018, 25, 1342–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, E.; Fairchild, G. Management Fashion: Lifecycles, Triggers, and Collective Learning Processes. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 708–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D.Ø.; Slåtten, K.; Berg, T. From Industry 4.0 to Industry 6.0: Tracing the Evolution of Industrial Paradigms Through the Lens of Management Fashion Theory. Systems 2025, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, P. UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES: A TYPOLOGY AND EXAMPLES. Int. Sociol. 1991, 6, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, A.; Pontrelli, V.; Oliva, L. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Environmental Social and Governance Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis of Governance Determinants. In Diversity and Equity in Accounting: Emerging Issues, Challenges and Opportunities; Agostini, M., Beretta, V., Demartini, M.C., Ghio, A., Trucco, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-3-031-78247-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jelodar, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and Topic Modeling: Models, Applications, a Survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 15169–15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of documents | ||

| Total | 51,666 | |

| Work Life | 5134 | |

| Work Style | 33,073 | |

| Human capital | 16,179 | |

| Union | Union of three words | 42 |

| Union of two words | 2636 | |

| Work Life & Work Style | 1737 | |

| Work Life & Human capital | 153 | |

| Work Style & Human capital | 746 |

| 2008–2017 | 2018–2019 | 2020–2022 | 2023–2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Life | WLB–2008–17 | WLB–2018–19 | WLB–2020–22 | WLB–2023–24 |

| Work Style | WS–2008–17 | WS–2018–19 | WS–2020–22 | WS–2023–24 |

| Human Capital | HC–2008–17 | HC–2018–19 | HC–2020–22 | HC–2023–24 |

| Exclusion Dataset | Dupulication Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| WLB | 3202 | 5134 |

| WS | 30,548 | 33,073 |

| HC | 15,238 | 16,179 |

| Total | 48,988 | 54,386 |

| Color | Description |

|---|---|

| Blue | promoting WS reform for employees |

| Brown | appointment of directors |

| Orange | our company focuses on HC to improve corporate value |

| Gray | childcare leave rate |

| Yellow | setting target indicators |

| Green | risk management for female employees’ empowerment |

| Purple | improvement of corporate value through productivity |

| Red | ensuring diversity |

| Light blue | work life balance |

| Pink | sustainable growth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoshino, Y.; Ikeda, Y. From Productivity to Sustainability?: Formal Institutional Changes and Perceptual Shifts in Japanese Corporate HRM. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209149

Hoshino Y, Ikeda Y. From Productivity to Sustainability?: Formal Institutional Changes and Perceptual Shifts in Japanese Corporate HRM. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209149

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoshino, Yusuke, and Yasuo Ikeda. 2025. "From Productivity to Sustainability?: Formal Institutional Changes and Perceptual Shifts in Japanese Corporate HRM" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209149

APA StyleHoshino, Y., & Ikeda, Y. (2025). From Productivity to Sustainability?: Formal Institutional Changes and Perceptual Shifts in Japanese Corporate HRM. Sustainability, 17(20), 9149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209149