1. Introduction

In today’s globalized economy, export competitiveness remains a critical driver of national economic development and prosperity. As global merchandise exports reached

$22 trillion in 2023 and environmental standards have become increasingly stringent across markets, the relationship between green practices and trade performance has gained unprecedented relevance. As international trade patterns evolve, countries and firms continually seek sustainable sources of competitive advantage in global markets. Concurrently, mounting environmental concerns have transformed the international trade landscape, with green practices increasingly serving as both regulatory requirements and strategic differentiators [

1,

2]. This intersection between environmental sustainability and export performance represents a vital yet complex domain meriting thorough investigation, particularly as economies worldwide navigate the transition toward more sustainable development models.

Green practices, ranging from environmental management systems to technological innovations addressing ecological challenges, have emerged as potentially powerful drivers of export competitiveness. These practices enable firms and countries to meet increasingly stringent environmental standards in destination markets, reduce operational costs through resource efficiency, and differentiate products based on environmental attributes [

3,

4]. Environmental management systems, exemplified by ISO14001 [

5] certification, provide formalized frameworks for identifying, monitoring, and mitigating environmental impacts throughout the value chain. Complementarily, green innovations (as reflected in environmental patents) represent technological solutions that can simultaneously address environmental challenges while enhancing productivity [

6,

7]. These dynamics can be understood through the lens of both institutional theory, which emphasizes the importance of legitimacy in international markets, and the resource-based view, which conceptualizes environmental capabilities as potential sources of competitive advantage [

8,

9].

Although a growing body of research has documented positive associations between various green practices and export outcomes, understanding the conditions that enhance or constrain these relationships remains underdeveloped. The effectiveness of green practices in boosting export performance likely depends on broader institutional and innovation ecosystem factors that shape how environmental practices are implemented, recognized, and valued in international markets. The institutional environment, particularly regulatory quality, may influence the credibility of environmental certifications and the enforcement of environmental standards [

10]. Similarly, innovation ecosystem characteristics, such as research and development intensity and financial market development, may affect firms’ capacity to successfully develop, implement, and commercialize environmental innovations [

11,

12].

Two critical gaps characterize the current literature. First, most existing studies employ firm-level data and conventional regression methods, limiting our understanding of macro-level dynamics and heterogeneous effects across different segments of the export distribution. Second, few studies systematically investigate the moderating role of both institutional and innovation ecosystem factors in an integrated framework, despite theoretical indications of their importance in shaping the relationship between environmental practices and international competitiveness.

Understanding these moderating influences holds substantial implications for both policy and practice. For policymakers, identifying institutional and innovation ecosystem factors that amplify the export benefits of green practices can inform the design of more integrated policy frameworks that simultaneously advance environmental and trade objectives. Such knowledge enables more targeted interventions that maximize returns on public investments in environmental governance and innovation support. For firms and industry associations, insights into how contextual factors shape the relationship between environmental practices and export success can guide strategic decisions regarding environmental certifications, innovation activities, and market entry strategies. Moreover, these insights contribute to addressing the ongoing debate regarding potential trade-offs between environmental sustainability and economic competitiveness, offering evidence on the conditions under which environmental practices can become sources of competitive advantage rather than regulatory burdens.

This study addresses two specific research questions: First, how do green practices (specifically ISO14001 certification and environmental patents) affect export performance across different quantiles of the export distribution? Second, to what extent do institutional factors (regulatory quality) and innovation ecosystem characteristics (R&D expenditure and financial market development) moderate these relationships?

To address these questions, we employ a comprehensive empirical approach using panel data from 30 European countries for the period 2012–2022. Our methodology combines conventional panel regression techniques with panel quantile regression, enabling examination of potential heterogeneity across different segments of the export distribution. This approach provides novel insights into the conditions under which green practices become sources of competitive advantage in international markets.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Panel Unit Root Test Results

Prior to conducting panel regression analysis, we verified the stationarity properties of our variables through complementary panel unit root tests that accommodate different assumptions regarding cross-sectional heterogeneity.

Table 3 presents results from both the Levin-Lin-Chu (LLC) test, which assumes homogeneous autoregressive parameters across countries, and the Im, Pesaran, and Shin (IPS) test, which permits heterogeneous parameters across panels.

Both testing procedures yield consistent evidence of stationarity across all variables. The test statistics uniformly reject the null hypothesis of nonstationarity at the 1% significance level. The concordance between these two approaches, one assuming parameter homogeneity and the other allowing for heterogeneity, provides robust confirmation that our variables exhibit stationary behavior throughout the panel.

This dual confirmation proves particularly valuable given the substantial economic and institutional diversity characterizing the 30 European countries in our sample. Countries at different stages of economic development and with varying structural characteristics may reasonably be expected to exhibit distinct persistence dynamics. The agreement between LLC and IPS results indicates that our stationarity conclusions hold regardless of whether we impose common or country-specific persistence structures. This robust foundation validates our subsequent application of standard panel regression techniques, eliminating concerns about spurious relationships that could arise from nonstationary data.

4.2. Panel Regression Results

To analyze the impact of green innovations and environmental management systems on export performance, we employed a baseline panel regression approach. Four distinct model specifications were estimated: a simplified model excluding control variables, pooled ordinary least squares (OLS), fixed effects, and random effects models, with results presented in

Table 4.

Model selection proceeded through rigorous specification tests, the results of which appear in

Table 5. The Hausman test yields a Chi-squared statistic of 44.767, significant at the 1% level, providing strong evidence against the null hypothesis that random effects estimates are both consistent and efficient. This result indicates systematic correlation between the country-specific effects and the regressors, establishing the fixed effects model as more appropriate than the random effects specification. The F-test similarly confirms that the fixed effects model is preferable to pooled OLS, with a test statistic of 240.95 rejecting the null hypothesis of zero fixed effects. These statistical diagnostics, considered alongside model fit criteria, establish the fixed effects specification as the most suitable for our analysis.

The fixed effects estimation reveals that ISO14001 certification exerts a statistically significant positive effect on export performance, with a coefficient of 0.07914, significant at the 1% level. This indicates that a 1% increase in ISO14001 certification corresponds to approximately a 0.08% increase in export value. This finding aligns with Zhou et al. [

3], who established that environmental certification functions as a “green passport” facilitating market access and product differentiation, and with Bellesi et al. [

17], who demonstrated that standardized environmental management systems confer competitive advantages, particularly in European markets where environmental standards are stringent and stakeholder scrutiny is pronounced.

In contrast to the panel regression results without control variables and pooled OLS, green patents lose statistical significance in the fixed effects specification once we account for country-specific heterogeneity and control variables. This suggests that the apparent patent-export relationship in simpler specifications may reflect omitted country-specific characteristics (such as overall technological sophistication, industrial structure, or innovation culture) rather than a direct causal pathway from environmental patents to exports. This finding underscores the importance of controlling for unobserved country heterogeneity when examining macro-level relationships, as failure to do so can lead to misleading inferences about the drivers of export performance.

The control variables reveal several notable patterns. GDP growth of trade partners demonstrates a strong positive association with exports, with a coefficient of 1.95789 significant at the 1% level. This substantial effect confirms that demand conditions in destination markets serve as a fundamental driver of export performance, consistent with standard trade theory. A one percentage point increase in trading partners’ GDP growth is associated with approximately a 2% increase in exports, highlighting the critical importance of external demand dynamics for export success.

The exchange rate variable proves statistically insignificant in the fixed effects specification, suggesting that within-country variation in exchange rates over our study period does not systematically affect export performance once we control for country and time fixed effects. This result may reflect several factors specific to the European context. First, many countries in our sample share the euro as their common currency, eliminating exchange rate variation in intra-EU trade, which constitutes a substantial proportion of total trade for most European nations. Second, even for non-euro countries, exchange rate pass-through to export competitiveness may be attenuated by global value chain integration, where imported intermediate inputs reduce the net competitive advantage from currency depreciation.

Foreign direct investment displays a positive coefficient of 0.00046, significant at the 10% level, indicating a modest complementarity between international capital flows and export expansion. This weak but positive relationship suggests that FDI may facilitate exports through mechanisms such as technology transfer, access to multinational production networks, or improvements in productive efficiency, though the economic magnitude of this effect appears relatively small in our sample.

Contrary to theoretical expectations, trade barriers exhibit a negative coefficient, though the effect is statistically insignificant. This counterintuitive sign may reflect reverse causality concerns or the complex nature of modern trade barriers, which increasingly take the form of nontariff measures that our simple tariff rate variable fails to capture adequately.

The relatively modest adjusted R-squared of 0.179 in the fixed effects model merits brief discussion. This value, while lower than those in pooled OLS or random effects specifications, reflects the stringent requirements imposed by fixed effects estimation, which explains only within-country variation after removing all between-country variation through country-specific intercepts. The lower R-squared in fixed effects models is typical and does not indicate poor model fit, but rather demonstrates that much of the variation in exports across countries stems from time-invariant country characteristics captured by the fixed effects themselves. The model’s primary purpose (identifying the within-country effects of our key variables while controlling for unobserved heterogeneity) is well-served by this specification.

4.3. Panel Quantile Regression Analysis

Building upon our baseline findings, we employed panel quantile regression techniques to investigate whether the effects of green innovations and ISO14001 certification vary systematically across different segments of the export performance distribution. This approach permits examination of heterogeneous treatment effects that conventional mean regression obscures, revealing whether countries at different export performance levels derive differential benefits from environmental practices. We estimated the model at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th quantiles of the export distribution.

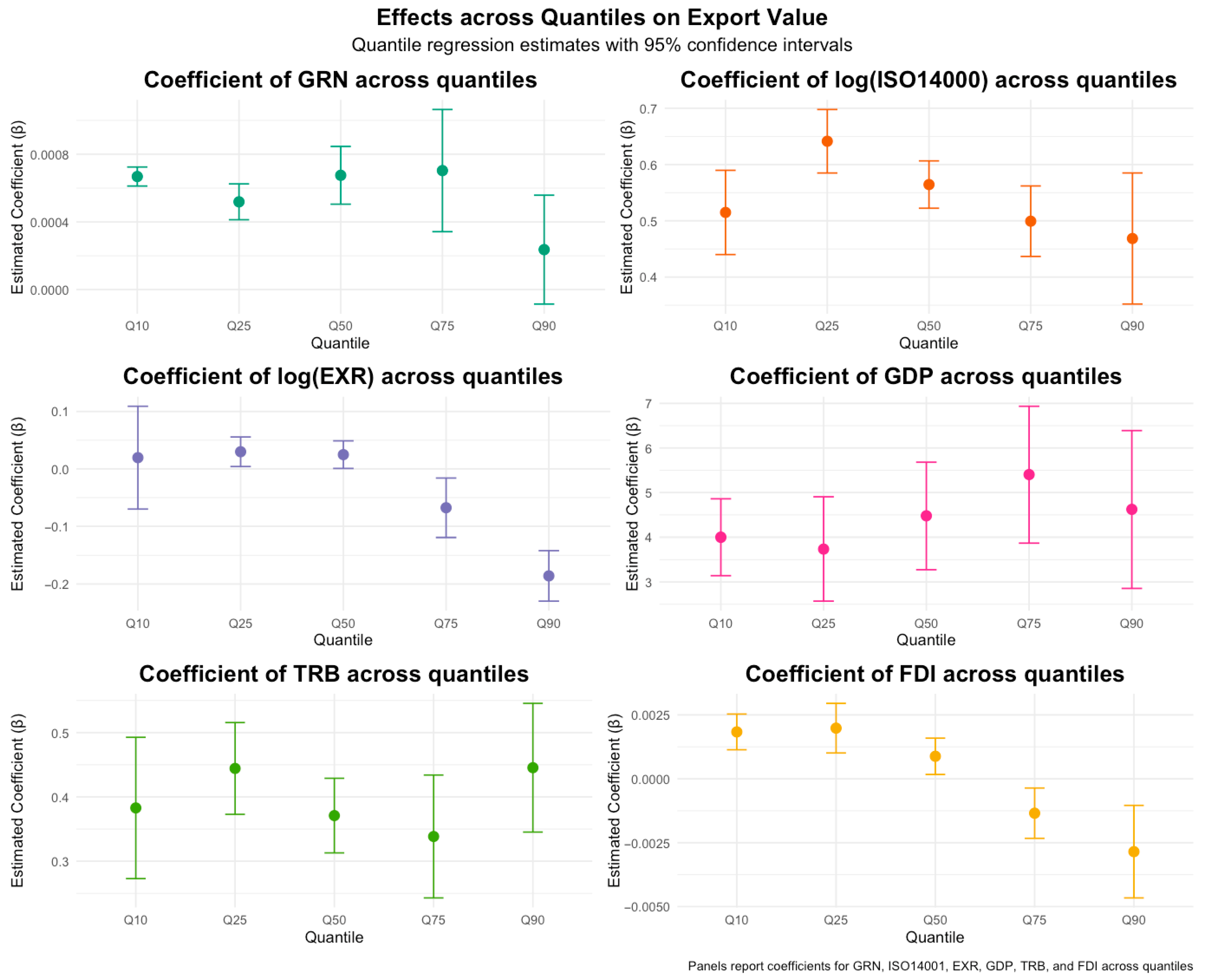

Figure 1 illustrates the estimated coefficients for our main variables across export performance quantiles, revealing substantial heterogeneity in how environmental practices influence exports at different performance levels.

The results presented in

Table 6 demonstrate striking patterns of heterogeneity, particularly for ISO14001 certification. The certification coefficient remains positive and statistically significant across all quantiles, ranging from 0.51487 at the 10th quantile to 0.46853 at the 90th quantile. While this might initially suggest relatively uniform effects, closer inspection reveals important nuances. The point estimates indicate somewhat stronger effects at the lower and middle quantiles compared to the upper quantiles, though the differences are not as pronounced as one might expect. This pattern suggests that environmental management system certification provides substantial export benefits across the entire performance distribution, with marginally stronger effects for countries not yet at the highest export levels. For countries at lower export quantiles, ISO14001 certification may serve as a critical signal of environmental commitment that helps overcome information asymmetries and facilitates market entry, particularly in environmentally conscious European markets. Even at higher quantiles, however, the persistent positive effects indicate that certification continues to provide value, possibly through enhanced reputation, regulatory compliance, or access to supply chains with stringent environmental requirements.

Green patents exhibit a more complex pattern across quantiles. The coefficients are positive and statistically significant at the 10th (0.00067), 25th (0.00052), 50th (0.00068), and 75th (0.00070) quantiles, all significant at conventional levels. However, at the 90th quantile, the coefficient diminishes to 0.00024 and loses statistical significance. This suggests that technological environmental innovations provide relatively consistent export benefits across most of the performance distribution but may offer diminishing returns at the very highest export levels. This pattern could reflect several mechanisms. Countries at lower-to-middle export performance levels may derive substantial competitive advantages from environmental innovations that help differentiate their products and meet increasingly stringent environmental standards in destination markets. At the highest export levels, where countries already possess sophisticated technological capabilities and established market positions, marginal additions to the environmental patent portfolio may provide less incremental value. Alternatively, this pattern might reflect a threshold effect whereby countries must reach a critical mass of environmental innovation before benefits materialize, but beyond very high levels, additional patents face diminishing returns.

The control variables display noteworthy variation across quantiles. GDP growth of trade partners demonstrates consistently positive and significant effects across all quantiles, with coefficients ranging from 3.73741 (25th quantile) to 5.40316 (75th quantile), all significant at the 1% level. The somewhat larger coefficients at the extremes suggest that both countries with lower export volumes and those with very high volumes exhibit particular sensitivity to demand conditions in partner markets. For lower-export countries, partner GDP growth may be especially critical because they lack the market diversification and established customer relationships that buffer more established exporters. For the highest exporters, the large coefficient may reflect their deeper integration into global markets and greater exposure to international business cycles.

Exchange rate effects exhibit an interesting progression across quantiles. The variable remains insignificant at lower quantiles but becomes negative and highly significant at the 90th quantile. This quantile-dependent pattern suggests that the relationship between exchange rates and exports varies substantially with export performance levels. The insignificance at lower quantiles may reflect the limited currency sensitivity of countries with smaller export volumes or the predominance of intra-EU trade conducted in euros. At the highest export levels, however, the significant negative coefficient requires careful interpretation. This counterintuitive sign may indicate that countries with the largest export volumes often experience currency appreciation as a consequence of their export success (reverse causality), or it may reflect the fact that highly export-oriented economies have substantial import content in their exports, reducing the net competitive benefit from depreciation. The euro-area context further complicates interpretation, as many high-export countries in our sample share a common currency.

Trade barriers display positive and significant coefficients across all quantiles, with values ranging from 0.33846 to 0.44546. This counterintuitive positive relationship between tariffs and exports likely reflects measurement issues or complex causal pathways rather than suggesting that higher barriers promote exports. The tariff variable may capture reverse causality if countries facing high export volumes subsequently raise tariffs on imports, or it may inadequately measure the complex array of nontariff barriers that increasingly characterize modern trade policy.

Foreign direct investment exhibits positive coefficients at lower quantiles but becomes insignificant or negative at higher quantiles. This pattern suggests that FDI plays a more important complementary role for countries at earlier stages of export development, possibly by facilitating technology transfer, management expertise, or access to global production networks. For countries already achieving high export volumes, additional FDI inflows may have neutral or even slightly negative associations with exports, perhaps reflecting competition for domestic resources or shifts toward more domestically oriented foreign investments.

Overall, the quantile regression results reveal that while both environmental certifications and green patents generally promote exports, their effects exhibit meaningful heterogeneity across the export performance distribution. ISO14001 certification demonstrates relatively robust effects throughout, while green patents show diminishing returns at the highest performance levels. These patterns underscore the importance of moving beyond average treatment effects to understand how environmental practices differentially influence countries at varying stages of export development.

4.4. Moderating Effects Results

Our investigation extends beyond direct effects to examine how institutional and innovation ecosystem factors moderate the relationship between environmental practices and export performance. We focus on three potential moderators: regulatory quality, research and development expenditure, and financial market development.

Table 7 presents the parameter estimates for interaction terms between these moderators and our environmental practice variables.

The results reveal differentiated moderating patterns across environmental practices and institutional factors. Regulatory quality demonstrates a positive and statistically significant moderating effect on the ISO14001-export relationship, indicating that higher regulatory quality amplifies the export benefits derived from environmental management system certification. This interaction effect proves economically meaningful: in countries with superior regulatory quality, ISO14001 certification yields substantially larger export gains than in countries with weaker regulatory institutions. Green patents, conversely, exhibit no significant moderation by regulatory quality, suggesting that the export benefits of technological environmental innovations operate independently of general regulatory quality.

Financial market development similarly exhibits a significant positive moderating effect on ISO14001 certification. This finding indicates that well-functioning financial markets enhance the extent to which environmental management certifications translate into export performance. As with regulatory quality, financial market development does not significantly moderate the green patents-export relationship.

Research and development expenditure fails to demonstrate significant moderating effects for either environmental practice. The interaction terms for both green patents and ISO14001 certification prove statistically insignificant, with the ISO14001 interaction even exhibiting a negative point estimate.

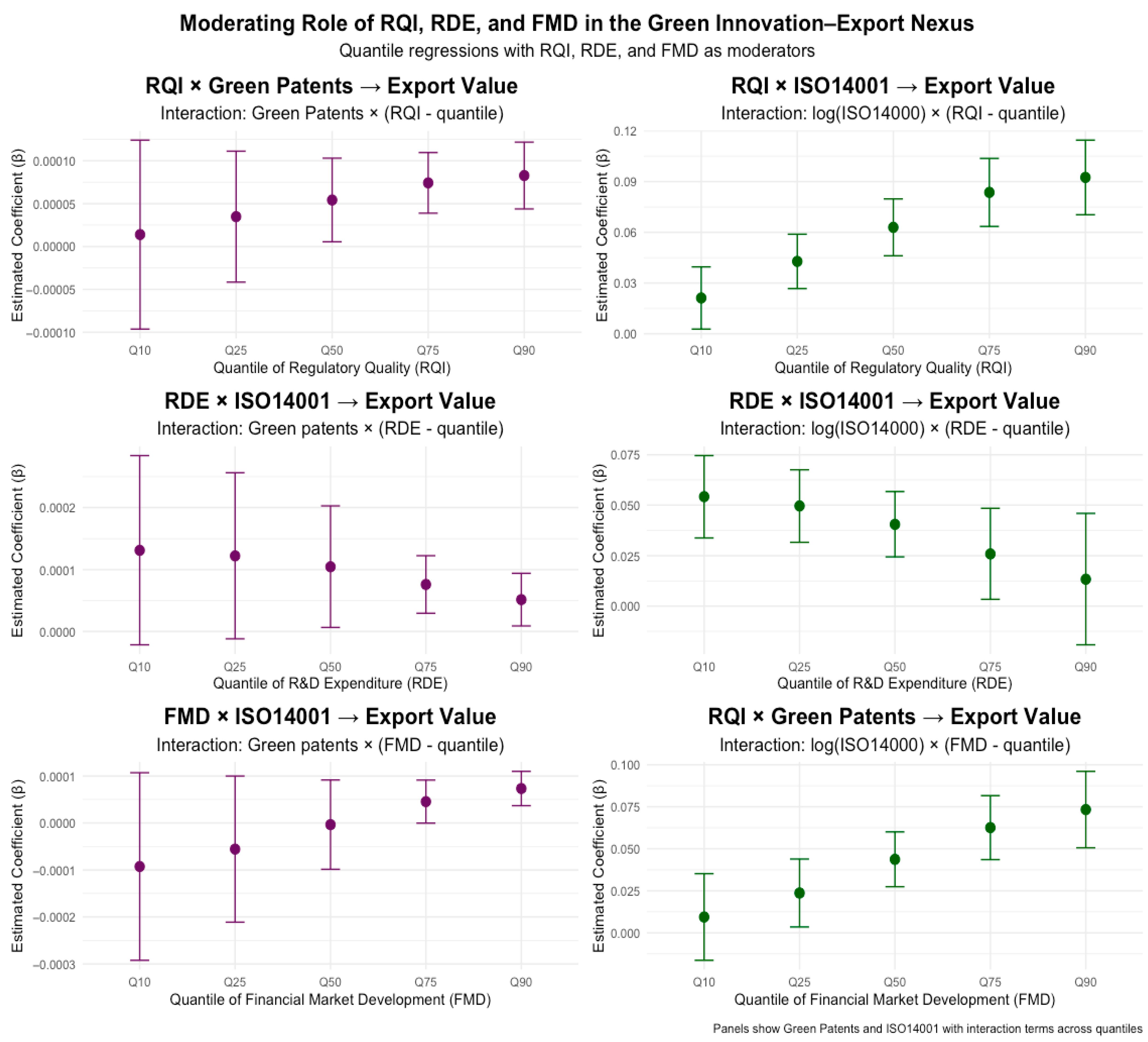

Figure 2 illustrates these moderating relationships across different quantiles of the moderator variables, revealing the conditional nature of institutional influences on environment-export linkages.

4.4.1. Regulatory Quality as Moderator

Table 8 presents marginal effects of environmental practices on exports evaluated at different quantiles of regulatory quality. The results demonstrate that ISO14001 certification’s export effect strengthens progressively as regulatory quality improves. At the 10th quantile of regulatory quality, ISO14001’s marginal effect stands at 0.02116, while at the 90th quantile, the effect reaches 0.09244. This progression reveals that environmental management certifications generate substantial export benefits primarily in institutional environments characterized by high regulatory quality.

This pattern aligns with theoretical predictions from institutional economics. High-quality regulatory institutions enhance the credibility and signaling value of voluntary environmental certifications through several mechanisms. First, robust regulatory oversight reduces the likelihood of certification “greenwashing,” ensuring that certified firms genuinely implement effective environmental management systems. This credibility enhancement proves particularly valuable in international markets, where information asymmetries between exporters and foreign buyers would otherwise create skepticism about environmental claims. Second, countries with superior regulatory quality typically possess well-functioning legal systems, transparent governance structures, and reliable contract enforcement mechanisms: complementary institutional assets that enable certified firms to fully leverage their environmental credentials in commercial relationships. Third, strong regulatory institutions may foster broader environmental consciousness among domestic stakeholders, creating ecosystem conditions that support and reinforce the commercial value of environmental practices.

The absence of significant moderation for green patents warrants explanation. Unlike certification-based environmental practices, which depend heavily on institutional credibility for their market value, technological innovations possess inherent technical characteristics that international buyers can evaluate more directly. Environmental patents embody tangible technological solutions whose commercial value derives primarily from their functional performance rather than from institutional validation. Moreover, intellectual property protection for patents operates through specialized legal frameworks (international patent agreements, technology licensing regulations, and innovation-specific enforcement mechanisms) that may function somewhat independently of general regulatory quality. This suggests that while regulatory institutions strongly influence the effectiveness of certification-based environmental signals, they prove less critical for technology-based environmental advantages.

4.4.2. Research and Development Expenditure as Moderator

Table 9 presents marginal effects evaluated at different R&D expenditure quantiles. Contrary to innovation systems theory predictions, R&D expenditure demonstrates no significant moderating influence on either environmental practice. ISO14001’s marginal effects range from 0.01333 (90th quantile) to 0.05420 (10th quantile), with most estimates failing to achieve statistical significance except at lower R&D quantiles. Green patents similarly exhibit no systematic variation in their export effects across R&D expenditure levels.

This null finding, while initially unexpected, aligns with several theoretical perspectives and empirical observations from the innovation literature, revealing important insights about the specificity required for institutional moderators to be effective. The theoretical framework of absorptive capacity developed by Cohen and Levinthal [

45] posits that organizations benefit from external knowledge only when they possess complementary internal capabilities to recognize, assimilate, and apply new information. Extending this logic to the national level, aggregate R&D expenditure may represent too diffuse a measure to capture the specific absorptive capacities required for environmental practices to generate export advantages. Countries may invest heavily in R&D while lacking the particular institutional configurations (environmental expertise, green technology commercialization pathways, or sustainability-oriented innovation networks) that would enable environmental practices to translate into competitive benefits.

Furthermore, Keller’s [

46] seminal work on international technology diffusion demonstrates that R&D investments generate substantial cross-border spillovers, with domestic investments often producing greater benefits for foreign countries than for the investing nation itself. This spillover dynamic proves particularly pronounced for environmental technologies, which exhibit strong public good characteristics that promote rapid international dissemination. Environmental innovations address global challenges (climate change, pollution, resource depletion) whose benefits transcend national boundaries, creating incentives for knowledge sharing and technology transfer. Consequently, a country’s R&D expenditure may enhance environmental innovation globally without necessarily strengthening the relationship between its own environmental practices and export performance. The knowledge generated through domestic R&D diffuses internationally, benefiting competitors and reducing the proprietary advantages that might otherwise accrue to domestic firms from environmental practices.

Rennings [

47] provides additional theoretical insight by distinguishing environmental innovation from conventional innovation, arguing that green technologies require specialized knowledge networks, regulatory frameworks, and institutional capabilities distinct from those supporting general innovation. Environmental innovations must simultaneously address technical performance criteria and environmental impact reduction: a dual objective requiring expertise that spans engineering, environmental science, regulatory compliance, and market development. Aggregate R&D expenditure, which encompasses diverse research domains from biotechnology to information technology to materials science, fails to capture whether a country possesses the specific green technology capabilities relevant for environmental practice effectiveness. A country might rank highly in overall R&D intensity while lacking the particular environmental innovation competencies needed to amplify the export benefits of ISO14001 certification or environmental patents.

Most fundamentally, the nonsignificant moderating effect reflects what Jaffe et al. [

48] term the “double externality problem” in environmental innovation. Green technologies face two distinct market failures: the traditional knowledge spillover problem that affects all innovations (reducing private appropriability of R&D investments) and the environmental externality problem specific to pollution control (limiting market rewards for environmental improvements). This dual externality structure means that environmental innovations systematically underperform commercially relative to their social value, and generic innovation capabilities (as proxied by aggregate R&D expenditure) prove insufficient to overcome these combined market failures. Rather, environmental innovations require targeted policy interventions specifically designed to address both externalities: intellectual property protections or subsidies to enhance appropriability, and environmental regulations or green procurement programs to create market demand for environmental improvements.

Our empirical findings thus reveal a critical insight about institutional complementarities in environmental policy. The effectiveness of environmental practices in generating export advantages depends not on general innovation capacity but on specific institutional conditions directly relevant to environmental management and green technology commercialization.

Regulatory quality matters because it enhances the credibility of environmental certifications and ensures enforcement of environmental standards. Financial market development matters because it facilitates capital-intensive environmental investments and enables firms to undertake complementary capability development. However, R&D expenditure, despite its obvious relevance to innovation broadly construed, operates at too aggregate a level and generates too many spillovers to effectively moderate the environment-export relationship. This finding carries important implications for policy design: countries cannot rely on increasing overall R&D expenditure to amplify the export benefits of environmental practices, but must instead develop targeted institutional capabilities (environmental technology commercialization programs, green finance instruments, sustainability expertise development) that directly support environmental practice effectiveness.

4.4.3. Financial Market Development as Moderator

Table 10 reveals that financial market development exerts a substantial positive moderating influence on ISO14001 certification, with marginal effects increasing from 0.00942 (10th quantile) to 0.07333 (90th quantile). This progression demonstrates that environmental management certifications generate their largest export benefits in countries with well-developed financial markets.

Well-developed financial markets facilitate the commercial exploitation of environmental certifications through several mechanisms. First, they reduce capital constraints that might otherwise prevent firms from making the substantial upfront investments required to implement and maintain ISO14001-compliant environmental management systems. Certification necessitates investments in monitoring equipment, training programs, process redesigns, and ongoing compliance verification: expenditures that generate returns only over extended periods. In countries with shallow financial markets, credit-constrained firms may forego certification despite its potential export benefits. Conversely, in countries with deep, liquid financial markets offering diverse financing instruments, firms can access capital for these investments at reasonable costs, enabling broader certification adoption and more effective implementation.

Second, sophisticated financial institutions possess superior capabilities for evaluating the commercial value of environmental management systems and incorporating environmental performance into credit assessments and investment decisions. Banks and investors in well-developed financial markets can better recognize certification as a signal of managerial quality, operational efficiency, and reduced regulatory risk, leading them to offer more favorable financing terms to certified firms. This creates stronger incentives for firms to pursue genuine environmental improvements rather than superficial compliance, enhancing the market value of certification.

Third, financial market development facilitates complementary investments that enable certified firms to fully leverage their environmental credentials in export markets. Access to diverse financing sources allows firms to simultaneously invest in environmental management systems, production technology upgrades, marketing capabilities, and international market development: complementary assets that amplify the export returns from certification. In less developed financial markets, firms may obtain certification but lack the capital for these complementary investments, limiting their ability to translate environmental credentials into export success.

As with regulatory quality, financial market development demonstrates no significant moderating effect on green patents. This consistent pattern across both institutional moderators reinforces the distinction between certification-based and technology-based environmental practices in their dependence on institutional context. While environmental management certifications require supportive institutional infrastructure to generate commercial value, technological innovations embody inherent capabilities that operate more independently of institutional conditions.

Overall, the moderating effects analysis reveals critical heterogeneity in how different environmental practices interact with institutional contexts. ISO14001 certification proves highly contingent on institutional quality, particularly financial market development and regulatory quality, with its export benefits materializing primarily in countries possessing well-developed supporting institutions. Green patents, conversely, generate export advantages through more direct, institution-independent pathways. These findings underscore the importance of coordinated policy approaches that align environmental practice promotion with institutional development, rather than treating environmental and institutional policies as independent domains.

4.5. Robustness Checks: Addressing Endogeneity Concerns

To address potential endogeneity from reverse causality and omitted variable bias, we employ instrumental variable (IV) estimation and System Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) alongside our baseline specification.

Table 11 presents comparative results across these estimation strategies.

The baseline two-way fixed effects model with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors accounts for cross-sectional dependence and serial correlation. Country fixed effects control for time-invariant characteristics including institutional quality and technological capabilities, while time fixed effects capture common temporal shocks. Both green patents and ISO14001 certification demonstrate significant positive associations with export performance.

The instrumental variable (IV) approach addresses reverse causality (whereby successful exporters may possess greater resources to invest in environmental practices) using lags 2–3 of green patents and ISO14001 as instruments. First-stage F-statistics (417.84 for green patents; 189.24 for ISO14001) substantially exceed the conventional threshold of 10, confirming strong instruments. However, the instrumental variable estimates show both variables losing statistical significance, though point estimates remain positive. Standard errors increase dramatically, with ISO14001 rising from 0.020 to 0.534, reflecting substantially greater uncertainty when accounting for endogeneity. The sample reduces from 330 to 240 observations due to lag construction.

System GMM estimation addresses both endogeneity and dynamic panel bias. The lagged export coefficient of 0.967 reveals extreme persistence, with 96.7% of current exports explained by previous export levels. This extraordinary persistence reflects path-dependence from established trade relationships, sunk costs, and accumulated market knowledge documented in trade literature. Conditional on this lagged structure, both environmental variables lose significance, as high persistence leaves minimal variation for other factors to explain. Diagnostic tests show mixed validity: the Sargan test supports instrument exogeneity and the AR(2) test confirms no second-order autocorrelation, though the AR(1) test could not be computed due to numerical instability from extreme persistence.

These robustness checks reveal important qualifications to our baseline findings. The consistent loss of significance across IV and GMM specifications suggests that baseline estimates likely represent upper bounds, potentially incorporating reverse causality. The maintained positive point estimates combined with inflated standard errors indicate considerable uncertainty rather than definitive rejection of positive effects. Alternatively, null results in dynamic specifications may reflect temporal mismatch between annual data and actual lag structures: environmental management implementation and green technology commercialization require multi-year horizons poorly captured by single-year lags. The extreme export persistence also indicates that structural factors and historical trajectories dominate short-run export determinants, limiting measurable impacts of any contemporaneous intervention. While direct effects weaken when addressing endogeneity, our primary contribution regarding institutional moderators examines conditional relationships potentially less susceptible to these concerns. These findings underscore the distinction between robust empirical associations and definitive causal effects, warranting cautious interpretation while suggesting directions for future quasi-experimental research employing stronger identification strategies.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Comparison with Existing Literature

Our findings advance understanding of environmental practices and export performance through three principal contributions that complement and extend existing research. First, we demonstrate that environmental management systems (ISO14001) and green technological innovations (environmental patents) operate through fundamentally different mechanisms in their associations with export performance. ISO14001 certification exhibits strong institutional contingency, showing stronger correlations with exports in countries with high regulatory quality and well-developed financial markets. This finding aligns with institutional theory’s legitimacy mechanisms while extending firm-level studies that documented positive effects without systematically examining institutional moderators. Our macro-level analysis reveals that this variation reflects systematic institutional differences rather than random firm heterogeneity. Countries with superior regulatory institutions provide the credibility infrastructure that makes certifications meaningful to international buyers, while weak institutions cannot effectively leverage voluntary environmental practices. Conversely, green patents demonstrate institution-independent associations, showing consistent relationships with exports across varying regulatory and financial contexts. This pattern supports the resource-based view’s emphasis on technological capabilities as intrinsic competitive advantages but challenges simplistic Porter hypothesis interpretations, treating all environmental practices as equivalent innovation drivers. Our evidence suggests technological innovations embody capabilities that international markets evaluate directly, rendering them less dependent on institutional validation than certifications.

Second, our panel quantile regression reveals that environment-export relationships vary systematically across performance distributions. ISO14001 demonstrates relatively consistent positive associations across quantiles with slightly stronger point estimates at lower-to-middle levels, suggesting that environmental management systems correlate with export performance throughout export development stages. Green patents exhibit significant associations across most quantiles but lose significance at the highest levels, indicating potential saturation effects. These patterns extend existing literature by revealing continuous heterogeneity: environmental practices show different association patterns depending on performance position, with relationships shifting as countries advance through export development stages.

Third, our finding that regulatory quality and financial market development significantly moderate ISO14001’s correlation with exports while R&D expenditure does not reveal critical institutional specificity. This challenges assumptions that general innovation capacity uniformly enhances all innovation-related advantages. As the environmental innovation literature articulates, green technologies face double externality problems: knowledge spillovers reduce appropriability while environmental externalities limit market demand. Our macro-level evidence confirms that aggregate R&D capacity proves insufficient without targeted institutional interventions addressing both externalities.

However, our robustness checks employing instrumental variable estimation and System GMM reveal important qualifications to these contributions. When explicitly addressing potential endogeneity through IV approaches using lagged instruments, both green patents and ISO14001 lose statistical significance, though point estimates remain consistently positive. Similarly, System GMM estimation accounting for dynamic panel bias shows negligible effects once we control for the extreme persistence in export performance (lagged coefficient = 0.967). These findings suggest that our baseline results likely represent upper bounds on causal effects, potentially incorporating reverse causality whereby successful exporters subsequently invest more in environmental practices. Alternatively, the null results in dynamic specifications may reflect temporal mismatch between our annual data frequency and the multi-year horizons over which environmental management implementation and green technology commercialization actually generate trade benefits.

Importantly, while direct effects weaken substantially when addressing endogeneity, our theoretical framework regarding institutional moderators (which examines how contextual factors shape environment-export linkages) may prove more robust. Moderating relationships depend less on identifying precise causal magnitudes than on understanding conditional associations and how institutional configurations alter the translation of environmental practices into competitive advantages. The finding that regulatory quality and financial market development strengthen ISO14001’s association with exports, while R&D expenditure does not, suggests that environmental practice effectiveness requires specific rather than generic institutional support. This theoretical insight remains valid whether the underlying direct effects represent causal impacts or complex bidirectional relationships.

5.2. Practical Implications and Policy Recommendations

Our quantile heterogeneity findings and differential institutional moderators yield policy implications that warrant careful interpretation given endogeneity concerns. Countries at lower export performance levels, where ISO14001 demonstrates stronger associations, may benefit from certification promotion through cost-sharing programs that reduce financial barriers to adoption. However, the significant regulatory quality moderation indicates that certification effectiveness depends on credible institutional frameworks. Countries should consider establishing independent oversight bodies with sufficient resources and technical expertise to conduct systematic auditing of certified firms, ensuring that results are publicly disclosed through accessible platforms that reduce information asymmetries for international buyers.

The significant moderation by financial market development indicates that well-developed financial systems enhance the extent to which environmental management certifications correlate with export performance. This suggests that countries with sophisticated financial infrastructure (including deep credit markets, developed bond markets, and efficient capital allocation mechanisms) create conditions enabling firms to access capital for the substantial investments certification requires. Policy could focus on developing broader financial system capacity that facilitates environmental investments, including credit facilities through development banks offering preferential financing terms and credit guarantee schemes providing coverage for financing to certified firms.

Countries at middle performance levels, where both ISO14001 and green patents show significant baseline associations, could create synergies through integrated support mechanisms that incentivize simultaneous pursuit of certification and technological innovation. Specialized financing vehicles targeting environmental patent commercialization, combined with investment criteria requiring certified environmental management systems, might exploit complementarities between certification signaling and patent technological capabilities. Financial system development priorities should include establishing diverse capital sources for environmental investments, with both debt and equity instruments supporting firms at different stages of environmental practice adoption and innovation.

However, these policy recommendations require substantial qualification given our robustness check findings. The loss of statistical significance in IV and GMM specifications suggests that simple promotion of environmental practices may not generate the export benefits our baseline results suggest. Rather, environmental practices appear embedded in complex causal webs involving bidirectional relationships with export performance and long-term institutional development. Effective policy likely requires patient, sustained institutional building in regulatory quality and financial market development rather than short-term interventions promoting specific practices. The extreme export persistence documented in our GMM results (0.967) further indicates that any policy intervention faces significant barriers to generating measurable short-run impacts on aggregate export performance.

Implementation should therefore proceed cautiously, recognizing uncertainty about causal mechanisms while leveraging insights about institutional complementarities. Initial phases might focus on establishing credible regulatory oversight and developing financial system capacity rather than aggressively promoting certification adoption. Intermediate phases could target measurable improvements in regulatory quality indices and financial system sophistication while carefully evaluating whether firms adopting environmental practices actually experience export gains. Longer-term objectives should aim for institutional quality levels supporting genuine competitive advantages from environmental practices, with realistic expectations about timeline and effect magnitudes based on our robustness check findings rather than baseline correlations.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated how institutional and innovation ecosystem factors moderate the relationship between green practices and export performance using panel data from 30 European countries for the period 2012–2022. Employing panel quantile regression alongside instrumental variable estimation and System GMM to address endogeneity, we identified critical institutional contingencies and performance-dependent heterogeneity in environment-export associations.

Our findings establish three principal contributions. First, ISO14001 certification and environmental patents demonstrate fundamentally different patterns: certifications exhibit strong institutional contingency, showing stronger correlations in countries with high regulatory quality and well-developed financial markets, while patents demonstrate institution-independent associations. Second, environmental practice benefits vary systematically across export performance distributions, with ISO14001 showing consistent positive associations throughout while green patents exhibit diminishing associations at the highest performance levels. Third, regulatory quality and financial market development significantly moderate certification’s association with exports, while R&D expenditure shows no moderation, indicating that environmental practices require targeted institutional support rather than generic innovation infrastructure.

However, robustness checks reveal important qualifications. When explicitly addressing reverse causality through instrumental variable approaches, both green patents and ISO14001 lose statistical significance, though point estimates remain consistently positive. System GMM estimation reveals extreme export persistence (lagged coefficient = 0.967), leaving minimal variation for contemporaneous variables to explain. These findings suggest that baseline results likely represent upper bounds, potentially incorporating bidirectional dynamics whereby successful exporters subsequently invest more in environmental practices. The relationships may also operate through longer-term mechanisms poorly captured by annual data, as environmental management implementation requires multi-year horizons to generate measurable benefits.

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment and suggest directions for future research. First, while our approaches address time-invariant heterogeneity, we cannot definitively establish causality despite robustness checks. The extremely high export persistence suggests that structural factors dominate short-run determinants. Future quasi-experimental research employing difference-in-differences around policy reforms or regression discontinuity designs would strengthen causal inference. Second, our measurement of green innovation through environmental patents does not encompass eco-efficient processes, green digitalization, or circular economy practices. Future research employing comprehensive eco-innovation indicators would provide a more complete understanding. Third, our focus on European countries limits external validity, as these nations generally possess more developed institutions than emerging economies. Cross-regional comparative research would illuminate alternative pathways in different institutional contexts.

Methodologically, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) [

49,

50] could investigate how different combinations of environmental practices, institutional factors, and country characteristics jointly produce export success, revealing equifinal pathways and configurational relationships our regression approach cannot capture. This approach, which has proven particularly valuable for analyzing complex causality in organizational and international business research [

51], would illuminate whether multiple distinct configurations generate success, whether institutional conditions substitute for one another, and whether factors promoting high performance differ from those preventing low performance.

Despite limitations, our findings contribute robust evidence that environmental practices show consistent positive associations with export competitiveness across multiple specifications. Our primary contribution (documenting how regulatory quality and financial market development moderate environment-export relationships) provides insights into institutional complementarities potentially less sensitive to endogeneity concerns, as moderating relationships examine conditional associations rather than requiring precise causal identification. These findings underscore the distinction between robust empirical associations and definitive causal effects. The baseline correlations we document appear economically meaningful, yet establishing causality requires stronger identification than observational panel data can provide. The challenge lies not in whether environmental practices and export performance relate positively but in understanding the causal mechanisms, temporal dynamics, and institutional conditions through which these relationships operate.