Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Water Reuse via Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation of Trypan Blue Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: XGBoost-Based Performance Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

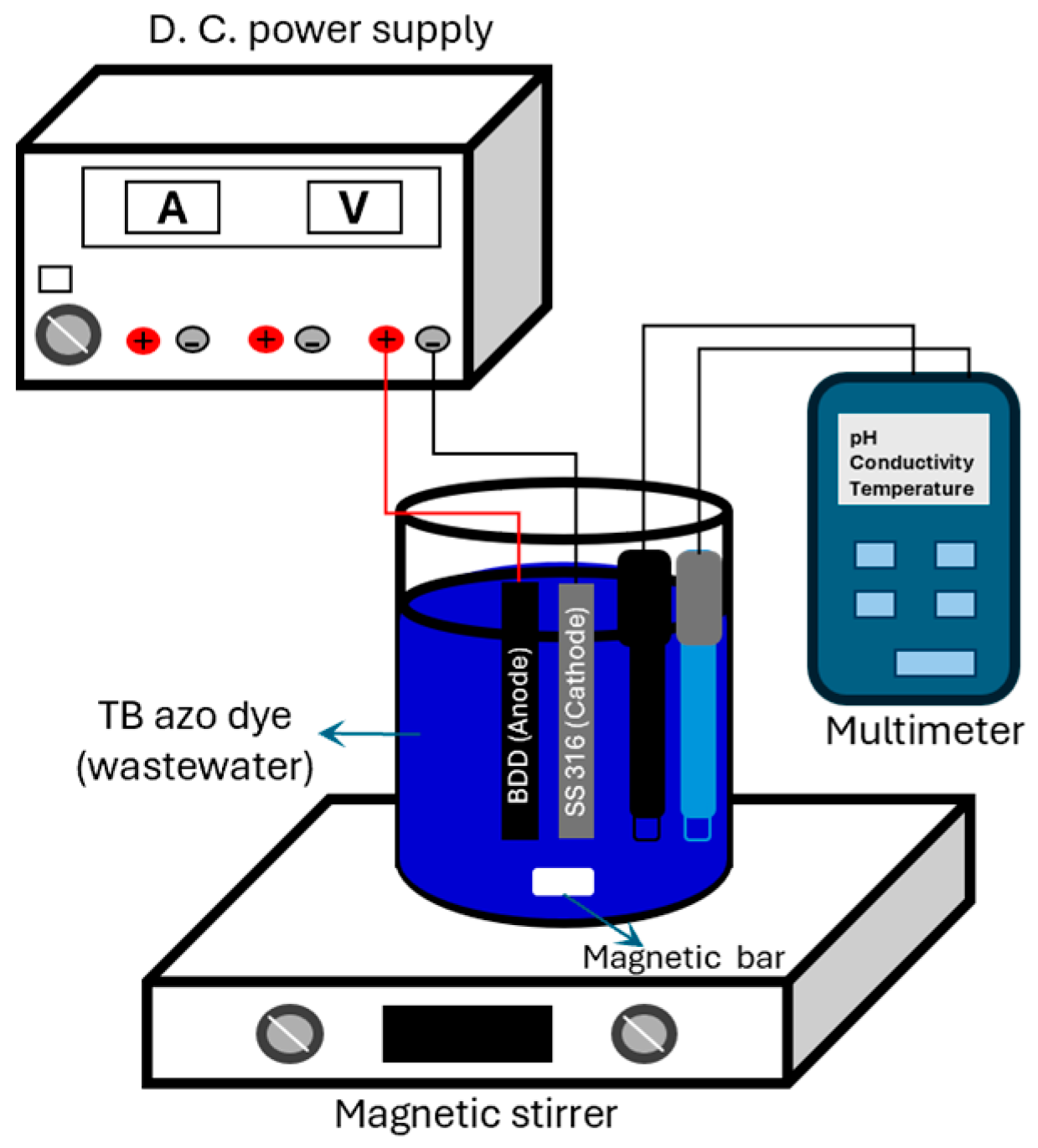

2.1. Experimental Equipment and Materials

2.2. Data Analysis Methods

eXtreme Gradient Boosting Algorithm (XGBoost)

- -

- Learning Rate (eta): It determines the learning rate that the model can perform in each iteration. Smaller values (e.g., 0.01–0.3) allow the model to learn more consistently but at a slower pace [35].

- -

- Max Depth: It refers to the maximum depth of decision trees. As the depth of the tree increases, the model’s capacity to learn complex relationships increases, while the risk of overfitting also increases [35].

- -

- Subsample: It helps prevent overfitting by determining the proportion of training data to be used in each iteration [42].

- -

- Colsample_bytree: It defines the ratio of features to be used for each tree. In addition, this parameter increases the generalization ability by increasing the diversity of the model.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of the Operational Parameters

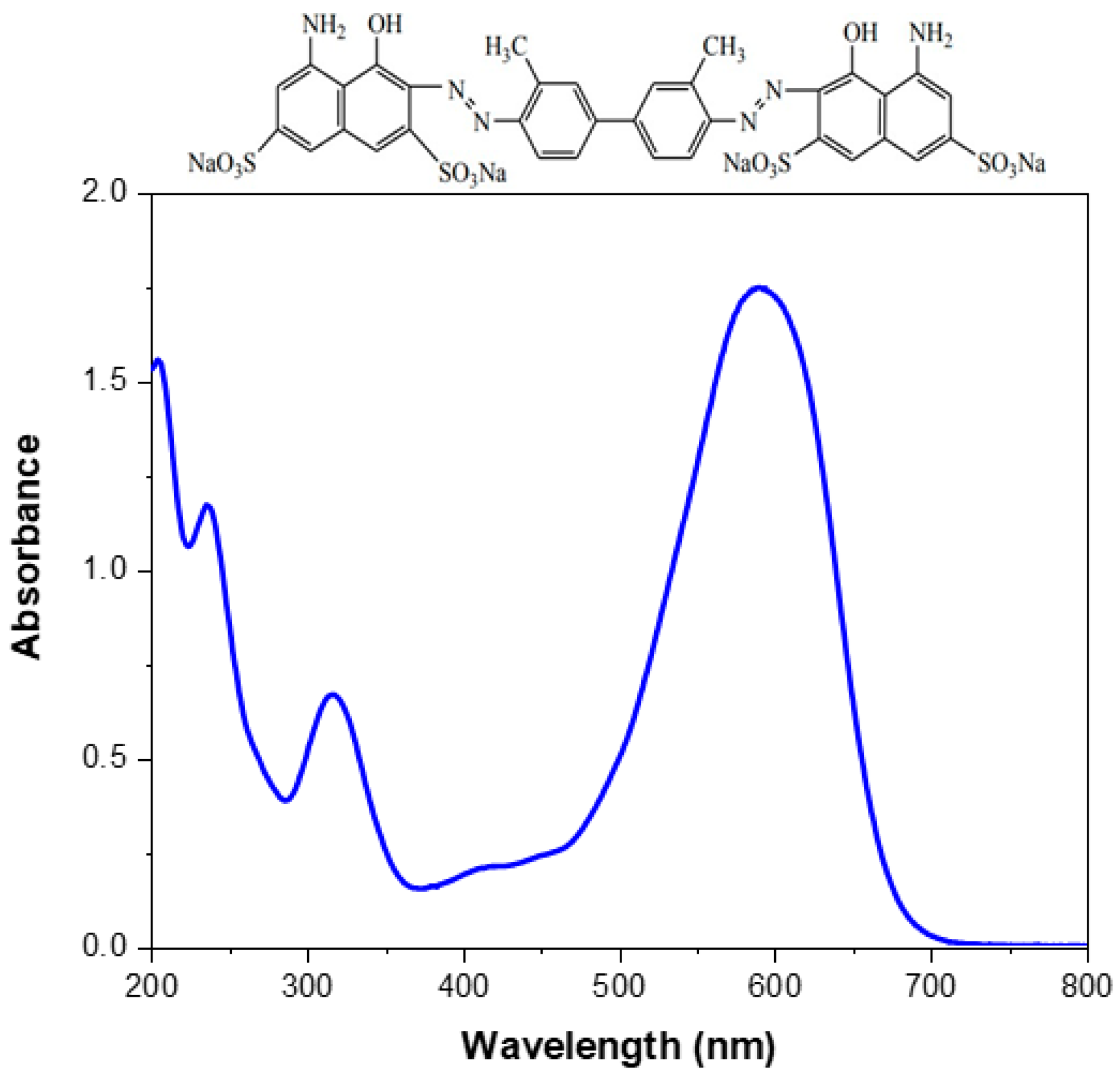

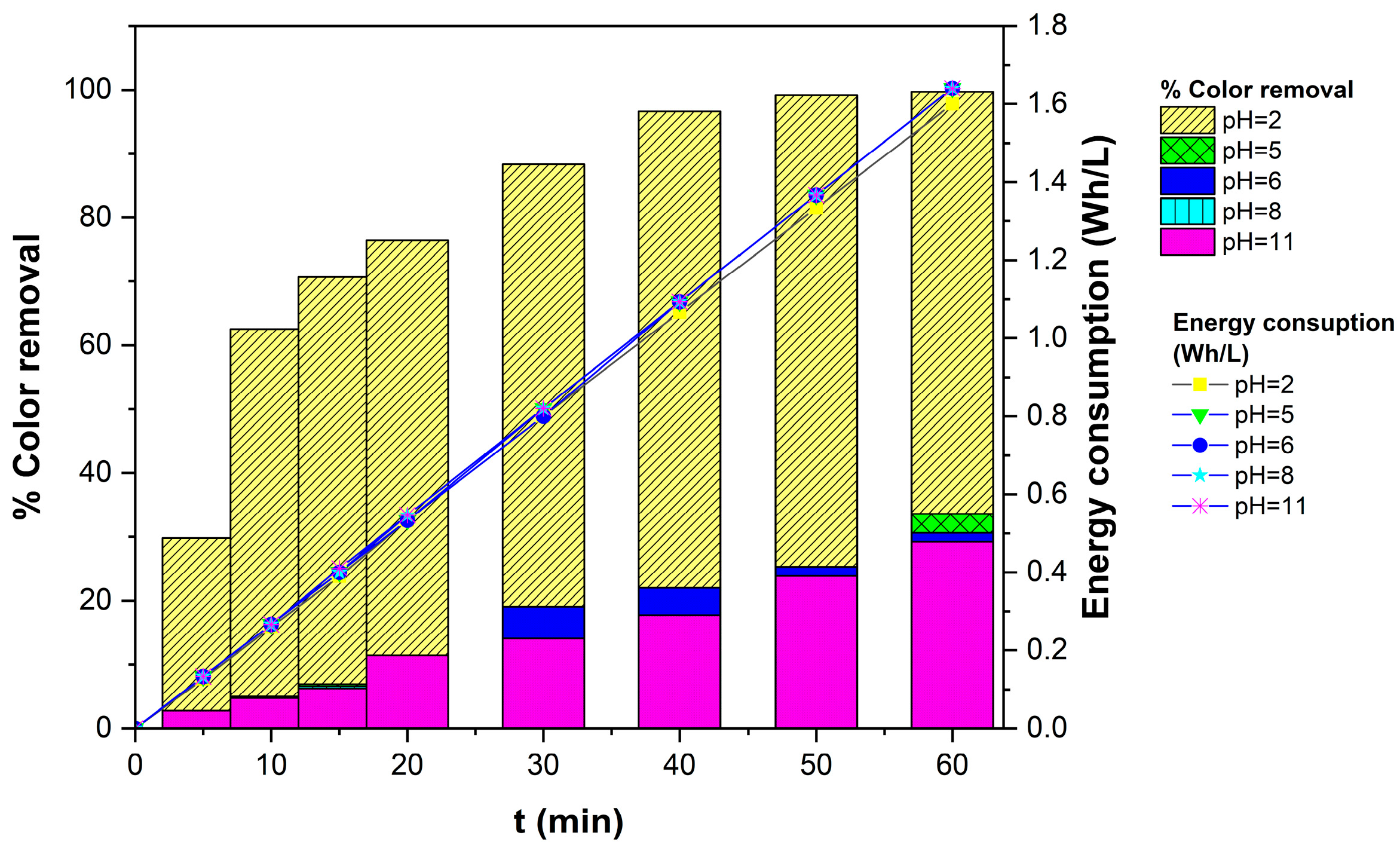

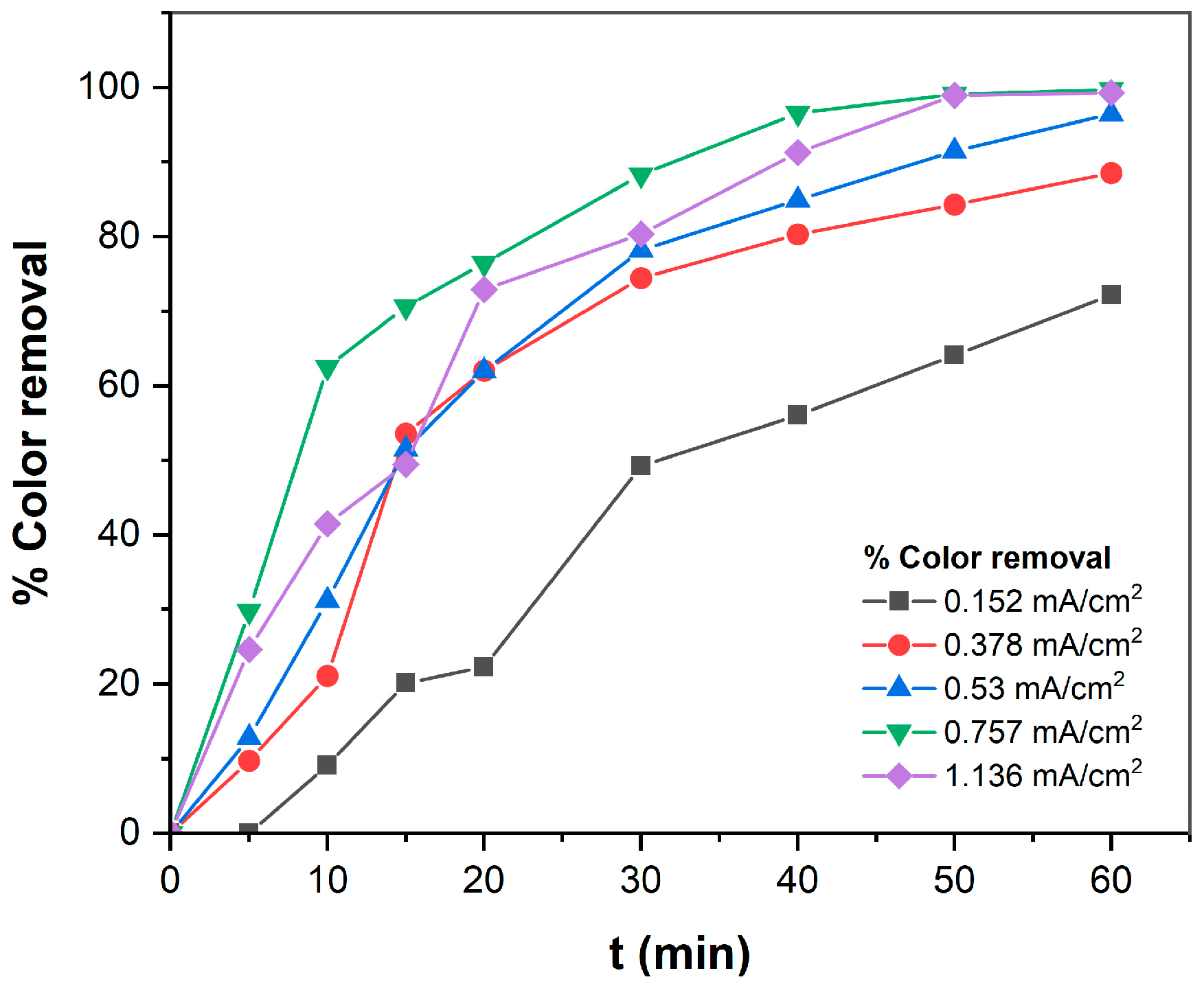

3.1.1. Effect of pH on TB Removal

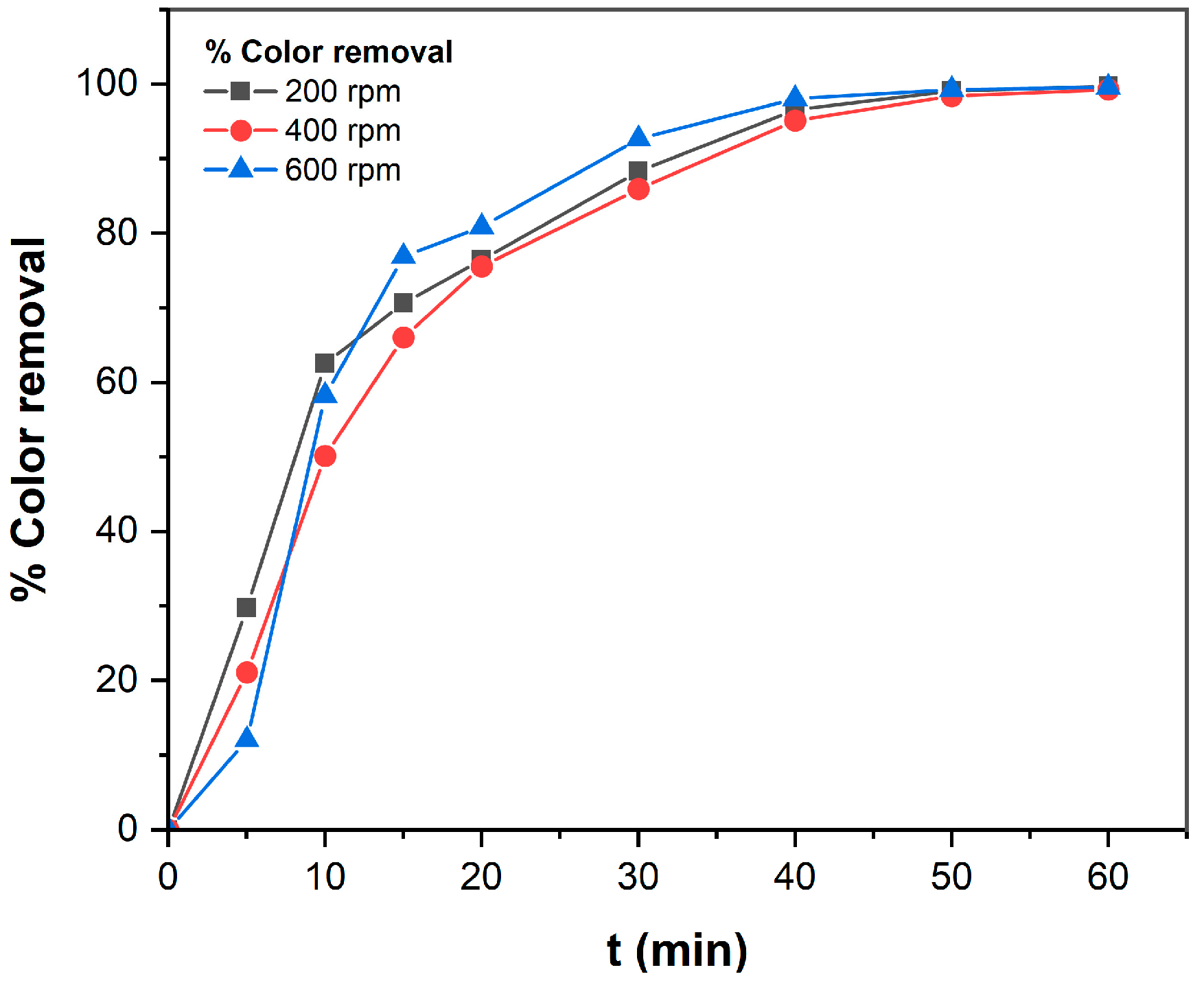

3.1.2. Effect of Mixing Speed on TB Removal

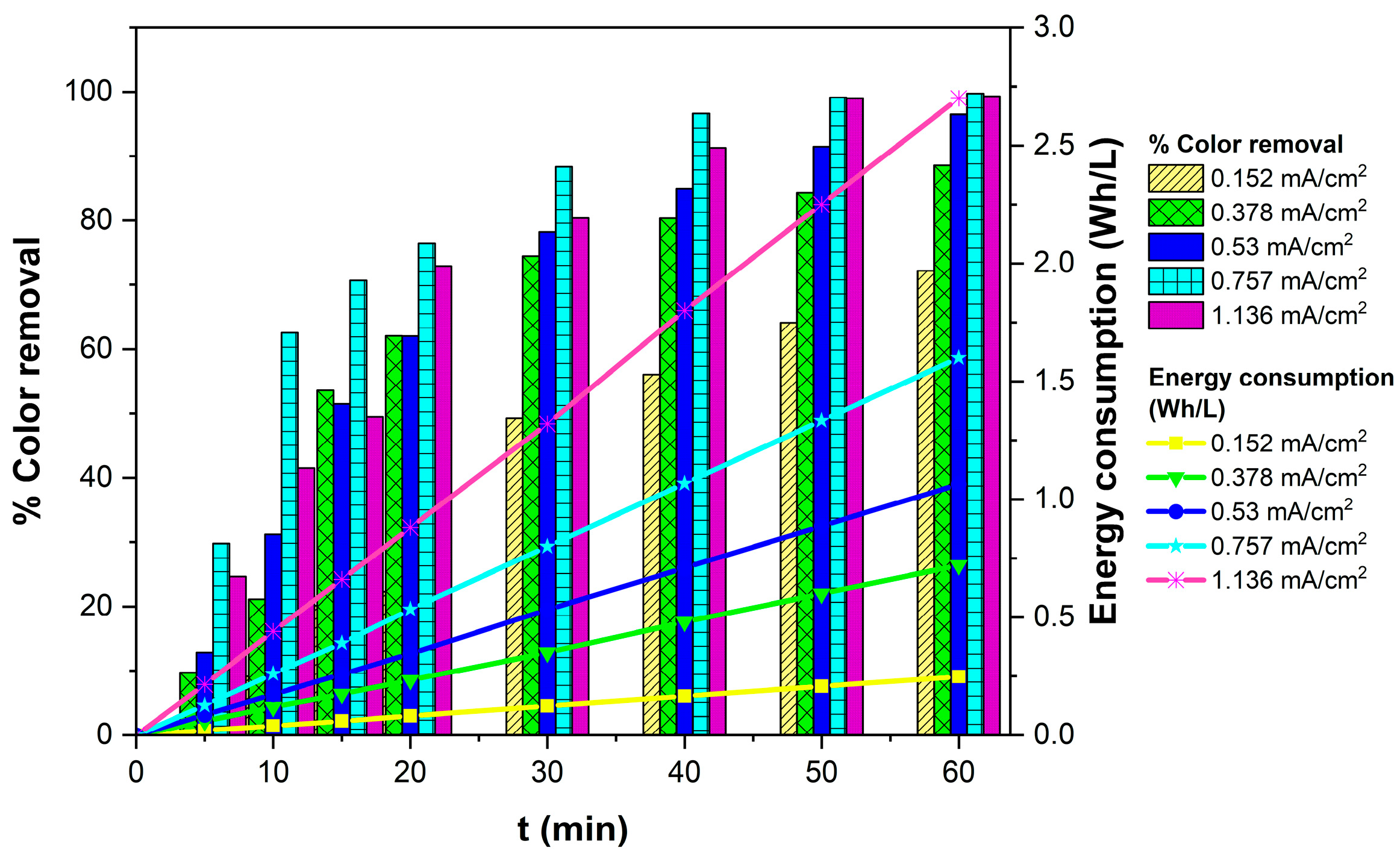

3.1.3. Effect of Current Density on TB Removal Efficiency and Energy Consumption

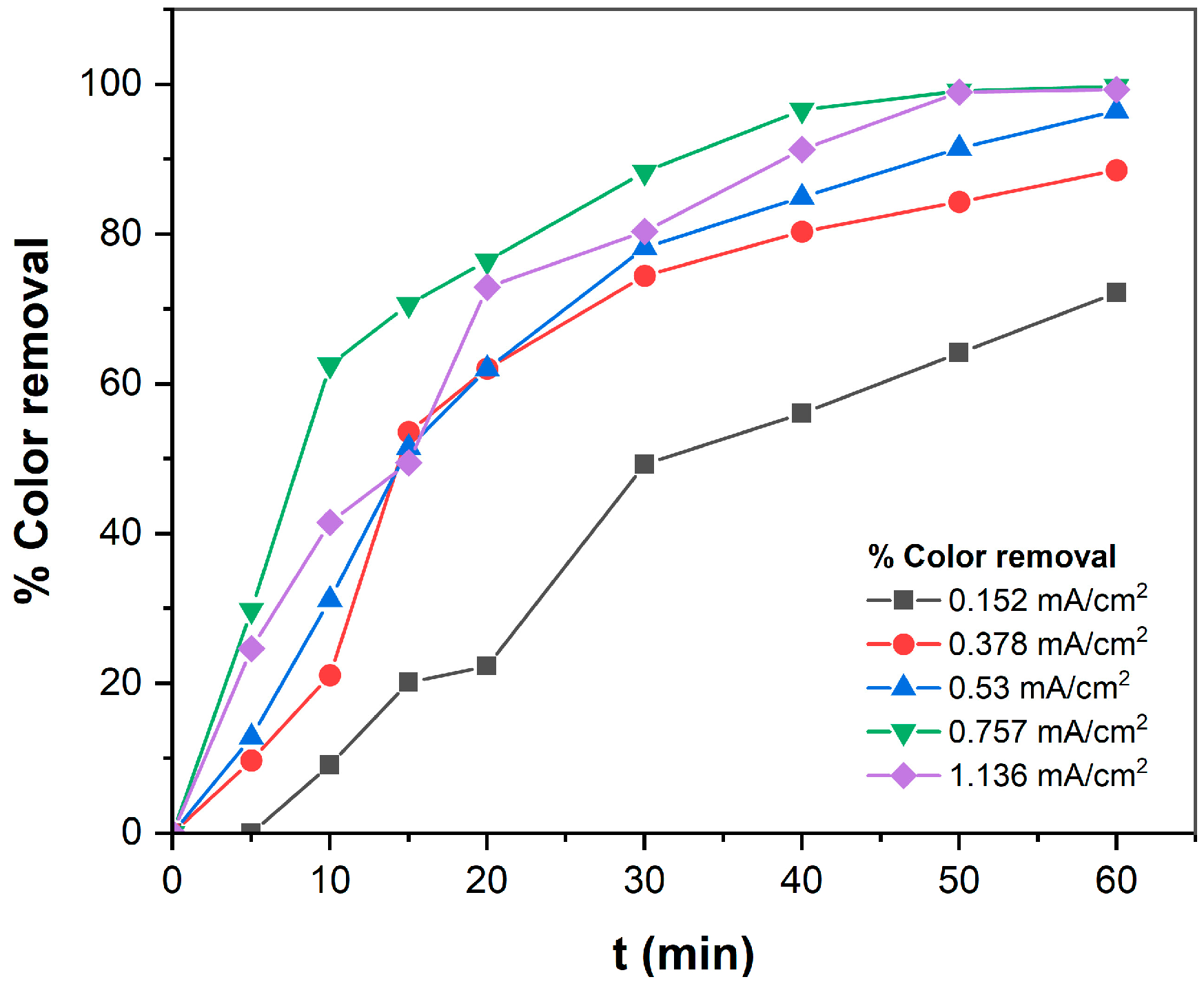

3.1.4. Effect of Initial Dye Concentration on TB Removal

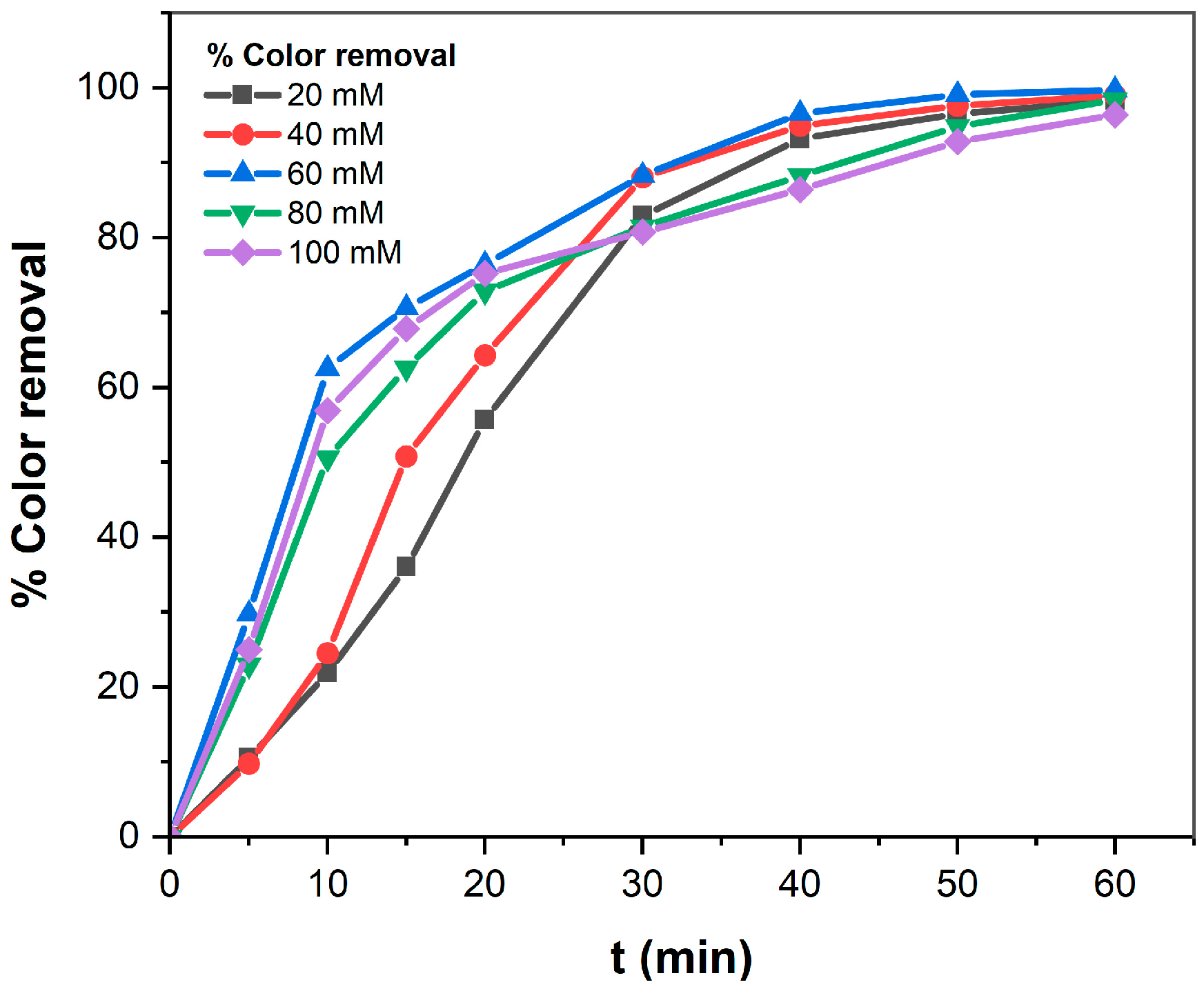

3.1.5. Effect of Support Electrolyte Concentration on TB Removal Efficiency

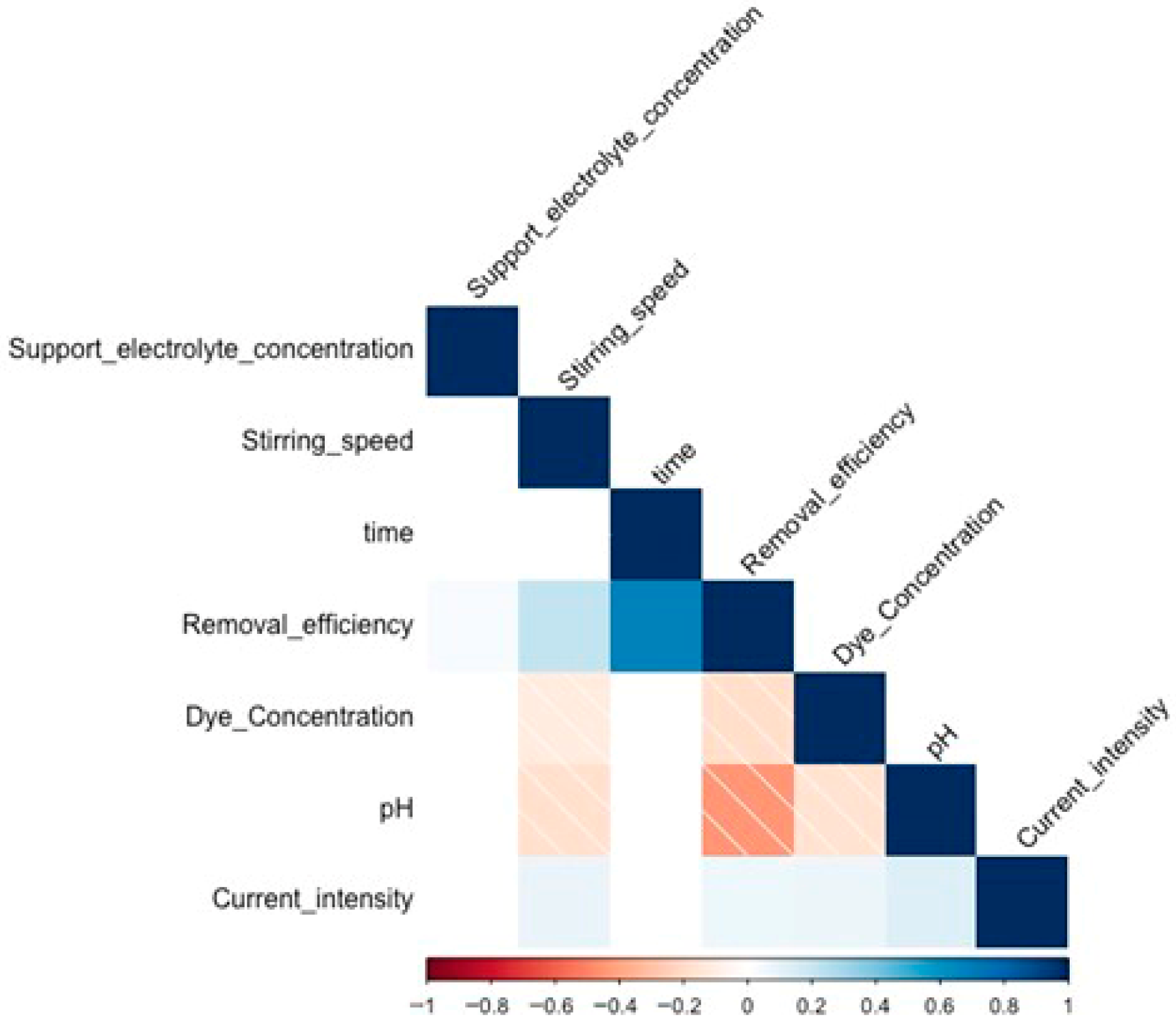

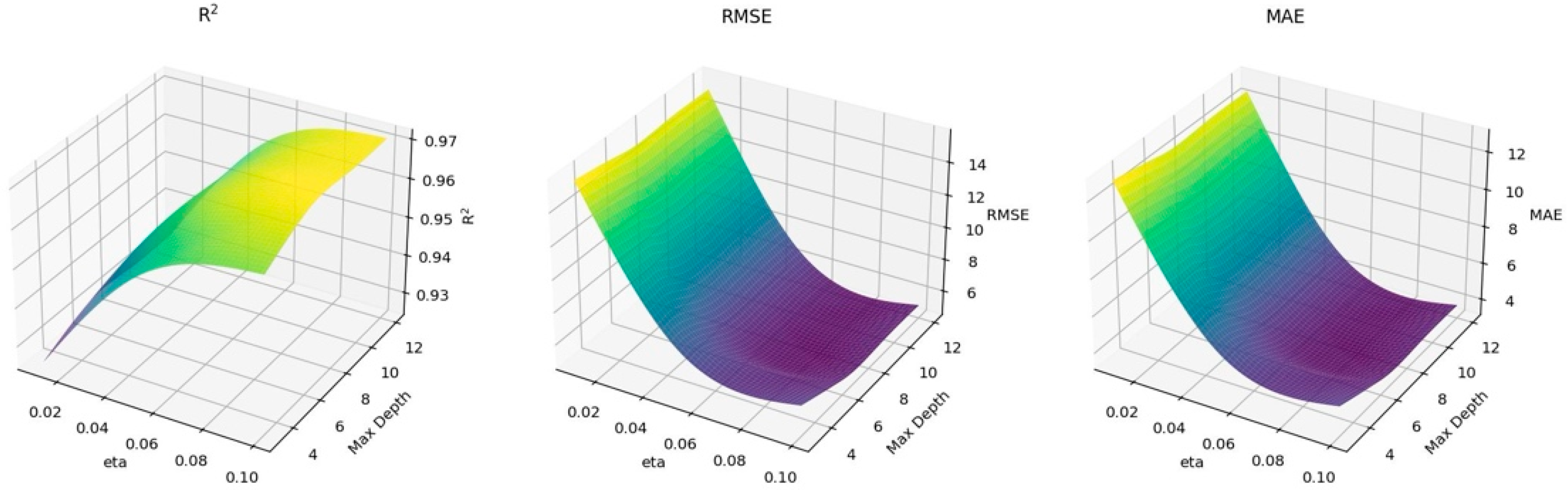

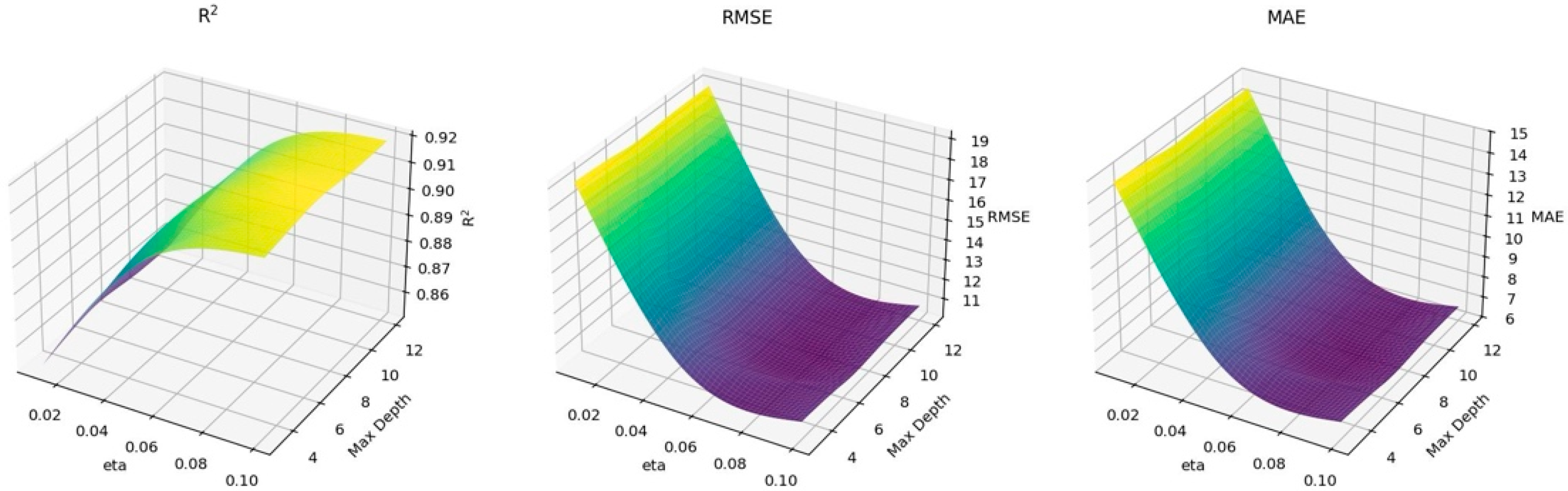

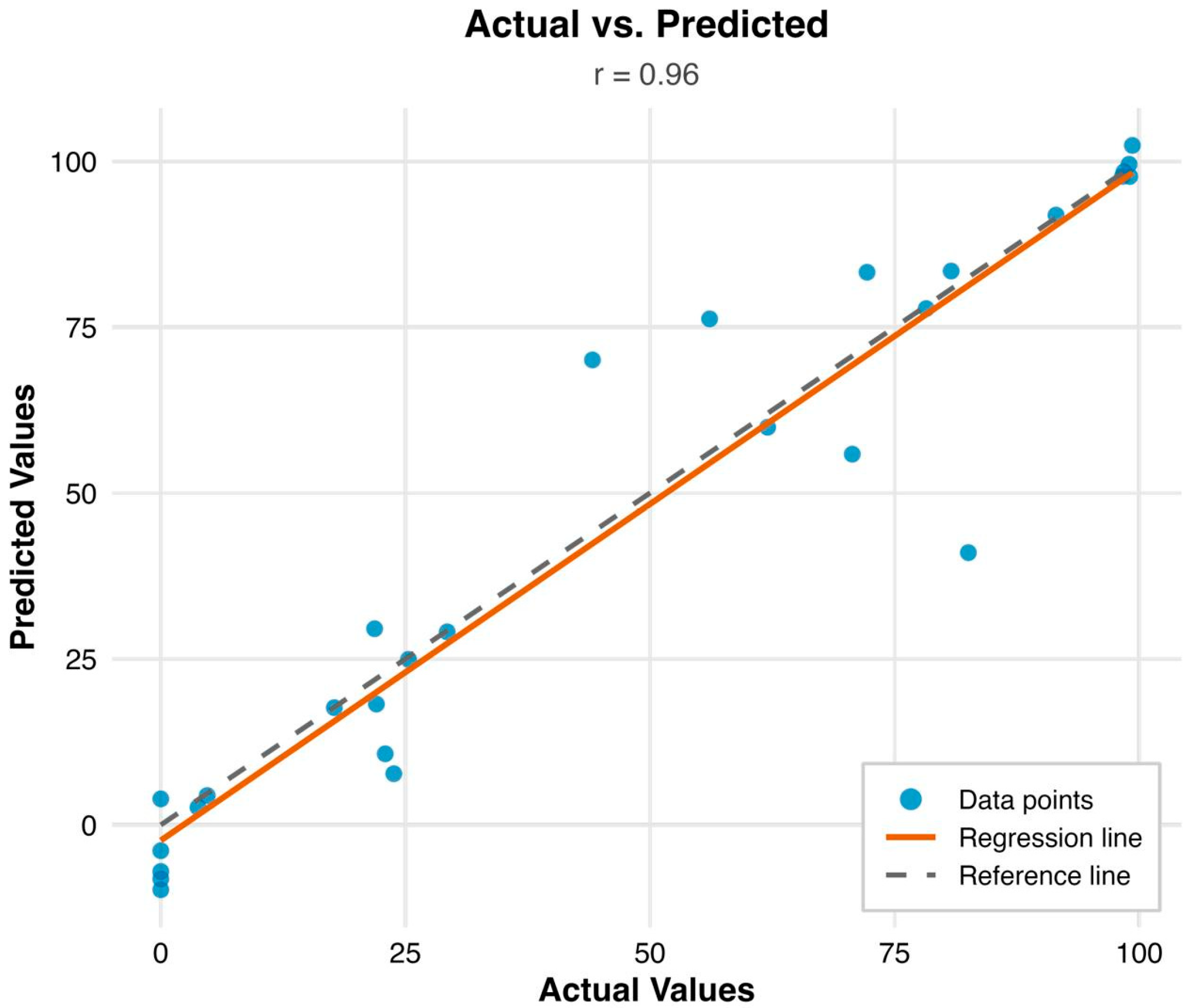

3.2. XGBoost Model Results

- -

- nrounds (Boosting Rounds): We tested this hyperparameter between 100 and 500, in increments of 100.

- -

- eta (Learning Rate): 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 values were used.

- -

- max_depth (Maximum Tree Depth): It tested between 3 and 12, in increments of 3.

- -

- gamma (Minimum Loss Reduction): Values of 0, 0.1 and 0.2 were used.

- -

- colsample_bytree (Variable Subsampling Rate per Tree): It tested between 0.5 and 0.9, in increments of 0.1.

- -

- min_child_weight (Minimum Leaf Node Weight): It tested between 1 and 10, in increments of 3.

- -

- subsample (Sampling Rate): It tested between 0.5 and 0.9, in increments of 0.1.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tırınk, S. Optimization of Coagulation Process Parameters for Reactive Red 120 Dye Using Ferric Chloride via Response Surface Methodology. BSJ Eng. Sci. 2025, 8, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tırınk, S.; Kulakcı, A.S. Engineering Sciences: Issues, Opportunities and Researches: Natural and Biosorbent Adsorbents for Decolorization of Azo Dyes: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends; Özgür Publications: Gaziantep, Türkiye, 2025; pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, L.; Marzona, M. Factors Affecting the Complete Mineralization of Azo Dyes. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argun, Y.A.; Tırınk, S.; Çakmakcı, Ö. Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Leachate Characteristics and Treatment Options. In Engineering Sciences and Technologies Researches; Kurt, H.I., Ergul, E., Eds.; Livre de Lyon: Lyon, France, 2023; pp. 35–89. Available online: https://bookchapter.org/kitaplar/Engineering_Sciences_and_Technologies_Researches.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Alzain, H.; Kalimugogo, V.; Hussein, K. A review of environmental impact of azo dyes. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2023, 10, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoulih, M.; Tigani, S.; Byoud, F.; El Rharib, M.; Saadane, R.; Pierre, S.; El Ghachtouli, S. Electrocoagulation-based AZO DYE (P4R) removal rate prediction model using deep learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 236, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Takkar, S.; Joshi, N.C.; Shukla, S.; Shukla, K.; Singh, A.; Varma, A. An integrative approach to study bacterial enzymatic degradation of toxic dyes. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 802544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faldu, P.; Kothari, V.; Kothari, C.; Rank, J.; Hinsu, A.; Kothari, R.K. Toxicity assessment of biologically degraded product of textile dye acid red g. Def. Life Sci. J. 2019, 4, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villabona-Ortíz, A.; Tejada-Tovar, C.; Navarro-Romero, D. Evaluation of parameters in the removal of azo Red 40 dye using electrocoagulation. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 50, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, T.J.; Dalbosco, V.; Bassin, J.P.; Lunelli, K.; da Costa, R.E.; Lapolli, F.R. Treatment of azo dye-containing wastewater in a combined UASB-EMBR system: Performance evaluation and membrane fouling study. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Radhakrishnan, R.C.; Johnson, J.K.; Joy, S.P.; Thomas, J. Ion-exchange mediated removal of cationic dye-stuffs from water using ammonium phosphomolybdate. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 242, 122488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, M.; Bujnowicz, S.; Bilińska, L. Fenton and electro-Fenton treatment for industrial textile wastewater recycling: Comparison of by-products removal, biodegradability, toxicity, and re-dyeing. Water Resour. Ind. 2024, 31, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, M.; Flores-Hidalgo, M.A.; Reynoso-Cuevas, L. Electrocoagulation Process: An Approach to Continuous Processes, Reactors Design, Pharmaceuticals Removal, and Hybrid Systems—A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Liu, J.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Leng, Y.; Yi, J.; Jiang, K.; Xing, W.; Yin, D.; Tang, W. Ni-EDTA Decomplexation and Ni Removal from Wastewater by Electrooxidation Coupled with Electrocoagulation: Optimization, Mechanism and Biotoxicity Assessment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tong, H.; Sun, B.; Liu, Y.; Ren, N.; You, S. Machine learning models for inverse design of the electrochemical oxidation process for water purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 17990–18000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, M.; Yildirim, R.; Isik, Z.; Karagunduz, A.; Keskinler, B.; Dizge, N. Optimization of the electrochemical oxidation of textile wastewater by graphite electrodes by response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.F.; Huang, C.P.; Hu, C.C.; Juang, Y.; Huang, C. Photoelectrochemical degradation of dye wastewater on TiO2-coated titanium electrode prepared by electrophoretic deposition. Sep. Purif. 2016, 165, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, M.; Stanković, D.; Manojlović, D.; Anđelković, I.; Milić, A.; Dojčinović, B.; Roglić, G. Study of the electrochemical oxidation of reactive textile dyes using platinum electrode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhay, A.; Jum’h, I.; Albsoul, A.; Abu Arideh, D.; Qatanani, B. Performance of electrochemical oxidation over BDD anode for the treatment of different industrial dye-containing wastewater effluents. Water Reuse 2021, 11, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.O.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Nature, Mechanisms and Reactivity of Electrogenerated Reactive Species at Thin-Film Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrodes during Electrochemical Wastewater Treatment. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 2379–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Niu, T.; Shi, P.; Zhao, G. Boron-Doped Diamond for Hydroxyl Radical and Sulfate Radical Anion Electrogeneration, Transformation, and Voltage-Free Sustainable Oxida-Tion. Small 2019, 15, 1900153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, C.N.; Ferreira, M.B.; Suzana, M.D.O.; de Moura Santos, E.C.M.; Leon, J.J.L.; Ganiyu, S.O.; Martinez-Huitle, C.A. Electrochemical oxidation of acid violet 7 dye by using Si/BDD and Nb/BDD electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, E250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Divyapriya, G.; Oturan, N.; Trellu, C.; Oturan, M.A. Environmental Applications of Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes: 1. Applications in Water and Wastewater Treatment. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 2124–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosler, P.; Girão, A.V.; Silva, R.F.; Tedim, J.; Oliveira, F.J. Electrochemical Advanced Oxi-Dation Processes Using Diamond Technology: A Critical Review. Environments 2023, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirés, I.; Brillas, E. Remediation of water pollution caused by pharmaceutical residues based on electrochemical separation and degradation technologies: A review. Environ. Int. 2012, 40, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Wahab, F.; Hussain, S.; Khan, S.; Rashid, M. Multi-object optimization of Navy-blue anodic oxidation via response surface models assisted with statistical and machine learning techniques. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Electrochemical Degradation of Methyl Red Using BDD and PbO2 Anodes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 6816–6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettlaff, A.; Tully, J.J.; Wood, G.; Chauhan, D.; Breeze, B.G.; Song, L.; Macpherson, J.V. A Closed Bipolar Electrochemical Cell for the Interrogation of BDD Single Particles: Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 485, 144035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, T.; Luu, T. Electrooxidation of Tannery Wastewater with Continuous Flow System: Role of Electrode Materials. Environ. Eng. Res. 2019, 25, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S. Electrochemical Wastewater Treatment Technologies through Life Cycle Assessment: A Review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2024, 11, e202400016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermentzis, K.; Karakosta, K.; Kokkinos, N.; Mitkidou, S.; Stylianou, M.; Agapiou, A. Photovoltaic-Driven Electrochemical Remediation of Drilling Fluid Wastewater with Simultaneous Hydrogen Production. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 41, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessie, T.; Seifu, L.; Dilebo, W. Waste to Wealth: Electrochemical Innovations in Hydrogen Production from Industrial Wastewater. Glob. Chall. 2025, 9, 2500043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, J.; Bastani, D.; Abdi, J.; Mahmoodi, N.M.; Shokrollahi, A.; Mohammadi, A.H. Assessment of Competitive Dye Removal Using a Reliable Method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1672–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Yang, J.; Lu, Y.; Hao, F.; Xu, D.; Pan, H.; Wang, J. BP–ANN Model Coupled with Particle Swarm Optimization for the Efficient Prediction of 2-Chlorophenol Removal in an Electro-Oxidation System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; Wu, M.; Steyskal, F.; Meng, J.; Xu, X.; Hou, P.; Tang, J. Henna Plant Biomass Enhanced Azo Dye Removal: Operating Performance, Microbial Community and Machine Learning Modeling. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Gören, N. Investigation of Electrocoagulation and Electrooxidation Methods of Real Textile Wastewater Treatment. AUJST-A 2019, 20, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañizares, P.; Gadri, A.; Lobato, J. Electrochemical Oxidation of Azoic Dyes with Conductive-Diamond Anodes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 3468–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Pollutants Using a Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: A Review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166, 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.S.; Kapoor, D.; Kalia, R.K.; Reddy, A.S.; Thukral, A.K. RSM and ANN Modeling for Electrocoagulation of Copper from Simulated Wastewater: Multi Objective Optimization Using Genetic Algorithm Approach. Desalination 2011, 274, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çanga Boğa, D.; Boğa, M.; Tırınk, C. Comparison of Nonlinear Functions to Define the Growth in Intensive Feedlot System with XGBoost Algorithm. Turkish JAF Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, version 2025.09.0+387; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Chen, T.; He, T.; Benesty, M.; Khotilovich, V.; Tang, Y.; Cho, H.; Chen, K.; Mitchell, R.; Cano, I.; Zhou, T.; et al. XGBoost: Extreme Gradient Boosting, R Package Version 1.7.8.1; Grin Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=xgboost (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Kuhn, M. caret: Classification and Regression Training, R Package Version 6.0-94; Scientific Research Publishing Inc.: Irvine, CA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, R Package Version 1.1.3; Grin Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamner, B. Metrics: Evaluation Metrics for Machine Learning, R Package Version 0.1.4; Grin Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Metrics (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Olvera-Vargas, H.; Wee, V.Y.H.; García-Rodríguez, O.; Lefebvre, O. Near-Neutral Electro-Fenton Treatment of Pharmaceutical Pollutants: Effect of Using a Triphosphate Ligand and BDD Electrode. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolotneva, E.; Trellu, C.; Crétin, M.; Mareev, S.A. A 2D Convection-Diffusion Model of Anodic Oxidation of Organic Compounds Mediated by Hydroxyl Radicals Using Porous Reactive Electrochemical Membrane. Membranes 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Cada, C.A.; Dalida, M.L.P.; Lu, M. Effect of Electrochemical Oxidation Processes on Acetaminophen Degradation in Various Electro-Fenton Reactors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, H207–H212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.P.; Rauf, M.A.; Hisaindee, S.; Nawaz, M. Experimental and Theoretical Study of the Spectral Behavior of Trypan Blue in Various Solvents. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1040, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, A.S.; Patil, S.; Sekar, N. Solvatochromism, Halochromism, and Azo–Hydrazone Tautomerism in Novel V-shaped Azo-azine Colorants–Consolidated Experi-Mental and Computational Approach. Color. Technol. 2016, 132, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, G.; Cañamares, M.; Prati, S.; Sánchez-Cortés, S. Study of the Azo-hydrazone Tautomerism of Acid Orange 20 by Spectroscopic Techniques: Uv–Visible, Raman, and Sur-Face-enhanced Raman Scattering. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2020, 51, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, C.M.; Schneider, P.M.; Song, K.T.; Yu, H.; Götz, R.; Haimerl, F.; Gubanova, E.; Zhou, J.; Schmidt, T.O.; Zhang, Q.; et al. How to assess and predict electrical double layer properties. Implications for electrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 12391–12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenova, T.A.; Kornienko, G.V.; Golubtsova, O.A.; Kornienko, V.L.; Maksimov, N.G. Electrochemical Degradation of Mordant Blue 13 Azo Dye Using Boron-Doped Diamond and Dimensionally Stable Anodes: Influence of Experimental Parameters and Water Matrix. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 30425–30440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, V.M.; León, C.P.D.; Nava, J.L.; Lanza, M.R. Electrochemical Degradation of RB-5 Dye by Anodic Oxidation, Electro-Fenton and by Combining Anodic Oxidation–Electro-Fenton in a Filter-Press Flow Cell. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 765, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, C.; Sousa, C.; Farinon, D.; Lopes, A.; Fernandes, A. Electrochemical Oxidation of Pollutants in Textile Wastewaters Using BDD and Ti-Based Anode Materials. Textiles 2024, 4, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.; Rodríguez, F.; Rivero, E.; Cruz-Díaz, M. Parametric Mathematical Modelling of Cristal Violet Dye Electrochemical Oxidation Using a Flow Electrochemical Reactor with Bdd and Dsa Anodes in Sulfate Media. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2018, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, C.; Waite, T. Hydroxyl Radicals in Anodic Oxidation Systems: Generation, Identification and Quantification. Water Res. 2022, 217, 118425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ren, H.; Luo, L. Gas Bubbles in Electrochemical Gas Evolution Reactions. Langmuir 2019, 35, 5392–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arts, A.; de Groot, M.T.; van der Schaaf, J. Current Efficiency and Mass Transfer Effects in Electrochemical Oxidation of C1 and C2 Carboxylic Acids on Boron Doped Diamond Electrodes. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert-Vilas, M.; Pechaud, Y.; Kherbeche, A.; Oturan, N.; Gautron, L.; Oturan, M.A.; Trellu, C. Hydrodynamics and Mass Transport in Anodic Oxidation Reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.-Z.; Gregory, J.; Campos, L.; Li, G. The Role of Mixing Conditions on Floc Growth, Breakage and Re-Growth. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirés, I.; Brillas, E.; Oturan, M.A. Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes: Today and Tomorrow. A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8336–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Sirés, I.; Oturan, M.A. Electro-Fenton Process and Related Electrochemical Technologies Based on Fenton’s Reaction Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6570–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Direct and Mediated Anodic Oxidation of Organic Pollutants. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6541–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Hernández, J.M.; Méndez-Tovar, M.; Guerra-Sánchez, R.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Nava, J.L. A brief review on environmental application of boron doped diamond electrodes as a new way for electrochemical incineration of synthetic dyes. Int. J. Electrochem. 2012, 2012, 154316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Brillas, E. Decontamination of Wastewaters Containing Synthetic Organic Dyes by Electrochemical Methods: A General Review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 87, 105–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, C.; Saldaña, A.; Hernández, B.; Acero, R.; Guerra, R.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Peralta-Hernandez, J.M. Electrochemical oxidation of methyl orange azo dye at pilot flow plant using BDD technology. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Srivastava, V.C. Electro-oxidation of nitrophenol by ruthenium oxide coated titanium electrode: Parametric, kinetic and mechanistic study. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 263, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo da Silva, L.D.; Gozzi, F.; Sirés, I.; Brillas, E.; De Oliveira, S.C.; Junior, A.M. Degradation of 4-aminoantipyrine by electro-oxidation with a boron-doped diamond anode: Optimization by central composite design, oxidation products and toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, I.J.; Silva, B.F.; Aquino, J.M. On the performance of a hybrid process to mineralize the herbicide tebuthiuron using a DSA® anode and UVC light: A mechanistic study. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 200, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Ibrahimi, S.; Elboughdiri, N.; Tekaya, M.A.; Ghernaout, D.; Hannachi, A.; Kolsi, L. Comparative Study of Chemical Coagulation and Electrocoagulation for the Treatment of Real Textile Wastewater: Optimization and Operating Cost Estimation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 22456–22476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, R.; Shukla, S.P.; Singh, R. Electrochemical Degradation of Reactive Dyes Using Stainless Steel and Graphite Electrodes: Evaluation of Electrode Dissolution and Deg-Radation Kinetics. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 246, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellouze, M.; Guesmi, A.; Kallel, M.; Ksibi, M.; Abdel-Wahab, A. Electrochemical Degradation of Anthraquinone Dye Alizarin Red S Using Boron-Doped Diamond and Lead Dioxide Anodes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenfoud, M.; Gadri, A.; Brillas, E. Electrochemical Oxidation of Acid Orange 7 Azo Dye on BDD Anode: Effect of Operating Parameters and Degradation Kinetics. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2014, 44, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, I.; Gadri, A.; Guenfoud, M. Electrochemical Oxidation of Textile Wastewater on BDD Anode: Kinetics, Degradation Pathway, and Energy Consumption. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 19792–19804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mojica, F.; Li, G.; Chuang, P. Experimental Study and Analytical Modeling of an Alkaline Water Electrolysis Cell. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 2365–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.; Haussener, S.; Brinkert, K. Impact of Gas Bubble Evolution Dynamics on Electrochemical Reaction Overpotentials in Water Electrolyser Systems. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2025, 129, 4383–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, Z.; Cui, J. Research on the Mechanism and Reaction Conditions of Electrochemical Preparation of Persulfate in a Split-Cell Reactor Using BDD Anode. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 33928–33936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrout, H.; Bousselmi, L. Chloride ions as an agent promoting the oxidation of synthetic dyestuff on BDD electrode. Desalin. Water Treat. 2012, 46, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clematis, D.; Cerisola, G.; Panizza, M. Electrochemical Oxidation of a Synthetic Dye Using a BDD Anode with a Solid Polymer Electrolyte. Electrochem. Commun. 2017, 75, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tırınk, S.; Böke Özkoç, H.; Arıman, S.; Alsaadawi, S.F.T. Unlocking Complex Water Quality Dynamics: Principal Component Analysis and Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines Integration for Predicting Water Quality Index in the Kızılırmak River. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidaleo, M.; Lavecchia, R.; Petrucci, E.; Zuorro, A. Application of a Novel Definitive Screening Design to Decolorization of an Azo Dye on Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbin, S.; Seyyedi, K. Removal of Acid Red 1 Dye Pollutant from Contaminated Waters by Electrocoagulation Method Using a Recirculating Tubular Reactor. LAAR 2017, 47, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, M.; Ghalwa, N.; Khedr, A.; Salem, M. Electrochemical Degradation of Reactive Yellow 160 Dye in Real Wastewater Using c/PbO2−, Pb + Sn/PbO2 + SnO2−, and Pb/PbO2 Modified Electrodes. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 691763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayeh, H. Reclamation and Reuse of Textile Dyehouse Wastewater by Elctrocoagulation Process. J. Eng. 2009, 15, 3985–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.L.; Couto, A.B.; Alves, S.A.; Lanza, M.R.; Ferreira, N. Influence of Supporting Electrolytes on Ro 16 Dye Electrochemical Oxidation Using Boron Doped Diamond Electrodes. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, H.; Can, O.T.; Guvenc, S.Y.; Can-Güven, E.; Varank, G. A Comparative Study on Decolorization of AB172 and BR46 Textile Dyes by Electrochemical Processes: Multivariate Experimental Design. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2025, 100, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tırınk, S.; Öztürk, B. Evaluation of PM10 Concentration by Using Mars and XGBOOST Algorithms in Iğdır Province of Türkiye. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 5349–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tırınk, S. Machine Learning-Based Forecasting of Air Quality Index under Long-Term Environmental Patterns: A Comparative Approach with XGBoost, LightGBM, and SVM. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0334252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gono, D.; Napitupulu, H.; Firdaniza, F. Silver Price Forecasting Using Extreme Gradi-Ent Boosting (Xgboost) Method. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Wang, J.; Zeng, C. An Optimized Machine Learning Framework for Predicting and Interpreting Corporate Esg Greenwashing Behavior. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Shahin, H.; Sabab, S.; Ashiq, H. Predicting the Shear Strength Parameter of Cohesionless Soil Using Machine Learning Techniques. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Cao, M.; Wang, C.; Yu, N.; Qing, H. Research on Mining Maximum Subsidence Prediction Based on Genetic Algorithm Combined with Xgboost Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, V.; Darvishsefat, A.; Arefi, H.; Griess, V.; Sadeghi, S.; Borz, S. Mode-Ling Forest Canopy Cover: A Synergistic Use of Sentinel-2, Aerial Photogrammetry Data, and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.; Ahmad, I.; Ahmad, M.; Wróblewski, P.; Kamiński, P.; Amjad, U. Prediction of Pile Bearing Capacity Using XGBoost Algorithm: Modeling and Performance Evaluation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, X.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, H.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X. Prediction of Influenza Outbreaks in Fuzhou, China: Comparative Analysis of Forecasting Models. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Jiang, K.; Yan, T.; Chen, G. XGBoost: An Optimal Machine Learning Model with Just Structural Features to Discover MOF Adsorbents of Xe/Kr. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9066–9076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Dreolin, N.; Canellas, E.; Goshawk, J.; Nerín, C. Prediction of Collision Cross-Section Values for Extractables and Leachables from Plastic Products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9463–9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Önder, H.; Tirink, C.; Yakubets, T.; Getya, A.; Matvieiev, M.; Kononenko, R.; Şen, U.; Özkan, Ç.Ö.; Tolun, T.; Kaya, F. Predicting Live Weight for Female Rabbits of Meat Crosses From Body Measurements Using LightGBM, XGBoost and Support Vector Machine Algorithms. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 11, e70149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Camacho, J.; Tırınk, C.; Parra-Cortés, R.I.; Bayyurt, L.; Uskenov, R.; Omarova, K.; Makhanbetova, A.; Chekirov, K.; Chay-Canul, A.J. Body Weight Estimation in Holstein × Zebu Crossbred Heifers: Comparative Analysis of XGBoost and LightGBM Algorithms. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 11, e70422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Current Density (mA/cm2) | 0.152, 0.378, 0.530, 0.757, 1.136 |

| Stirring Speed (rpm) | 200, 400, 600 |

| Initial Dye Concentration (mg/L) | 100, 200, 400 |

| pH | 2, 5, 6, 8, 11 |

| Supporting electrolyte concentration (Na2SO4, mM) | 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 |

| Na2SO4 Concentration (mM) | Conductivity (µS/cm) |

|---|---|

| 20 | 10,950 |

| 40 | 19,160 |

| 60 | 26,800 |

| 80 | 31,800 |

| 100 | 38,700 |

| Hyperparameters | ||||||

| Nrounds | Eta | Max_depth | Gamma | Colsample_bytree | Min_child_weight | Subsample |

| 500 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Model evaluation criteria | ||||||

| Train | Test | |||||

| RMSE | 2.101 | 8.204 | ||||

| MAE | 1.528 | 4.089 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9966 | 0.954 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tırınk, S. Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Water Reuse via Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation of Trypan Blue Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: XGBoost-Based Performance Prediction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209134

Tırınk S. Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Water Reuse via Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation of Trypan Blue Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: XGBoost-Based Performance Prediction. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209134

Chicago/Turabian StyleTırınk, Sevtap. 2025. "Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Water Reuse via Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation of Trypan Blue Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: XGBoost-Based Performance Prediction" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209134

APA StyleTırınk, S. (2025). Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Water Reuse via Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation of Trypan Blue Using Boron-Doped Diamond Anode: XGBoost-Based Performance Prediction. Sustainability, 17(20), 9134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209134