1. Introduction

In the 21st century, humanity faces serious social (e.g., widening inequalities, armed conflicts, migration, social anxiety), environmental (e.g., climate change, resource depletion, degradation), and economic challenges (e.g., unemployment, unequal wealth distribution). These problems, resulting from complex interactions between people and the environment, generate uncertainty and require competencies enabling effective, responsible action [

1]. One such key competence is creativity, essential for implementing sustainable development (SD) principles and fostering large-scale transformations toward more sustainable societies [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Creativity supports coping with uncertainty, encourages innovative solutions, and facilitates social change. Also, creativity is seen as an aspiration to re-create and discover new paths to accelerate the transitions towards sustainability [

8].

Recent literature reviews emphasize that creativity not only supports individuals in coping with uncertainty, but is also treated as an integrative leverage point for the transition to sustainable development [

8]. This means that innovative thinking, generating alternative solutions, and combining different perspectives are key mechanisms for achieving the SDGs. A lot of evidence from more recent empirical and policy studies further clarifies how creativity links with sustainable development. Kanzola & Petrakis [

9] in

The Sustainability of Creativity show that creativity is deeply rooted in social identity and that factors such as health, maturity, a positive attitude towards cultural change, social stability, environmental care, and material and non-material incentives shape the creative dynamism of individuals and communities. This suggests that creativity not only generates solutions, but that social and cultural conditions themselves must be favourable for a creative approach to materialize in pro-sustainability actions. The report ‘The Green Deal Ambition: Technology, Creativity and the Arts for Environmental Sustainability’ [

10] emphasizes that initiatives such as the New European Bauhaus aim to transcend sectoral barriers through collaboration between the arts, technology, science, institutions, and citizens, creating a more beautiful, inclusive, and socially sustainable space. Creativity in this context acts as a link between aesthetics, technology, and environmental action, creating space for translational innovations that combine social and ecological values. Authors of the study

Creative and Happy Individuals Concerned about Climate Change [

11] analyzed data from the European Social Survey and showed that people who declare higher creativity also report stronger concern about climate change and a sense of personal responsibility for mitigating it. This indicates that creativity can be not only a tool for generating new ideas, but also an element that motivates social awareness and readiness to take pro-environmental action.

In education, creativity is a priority both in Polish regulations and European frameworks. The Regulation of the Minister of Science and Higher Education [

12], the European Framework of Key Competences [

13], and the Integrated Skills Strategy 2030 [

14] emphasize that teachers should possess and develop this competence to stimulate students’ creative competence, problem-solving, and openness to innovation. EU strategic documents, such as the Council Conclusions on Promoting Creativity and Innovation [

15] and the Creative Europe Programme 2021–2027 [

16], underline creativity as vital for Europe’s cultural, social, and economic growth.

Within the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Goal 4 highlights the need to ensure equal access to education and to develop competencies for the future—including creativity—to address dynamic social, technological, and environmental changes. Creativity enables innovative problem-solving, cross-cultural collaboration, and adaptability, which are essential for building sustainable societies.

The aim of this study is to determine the declared level of creative competence among students of Kraków universities preparing for the teaching profession. The research question was as follows: What is the declared level of creativity competence among candidates for the teaching profession studying at Kraków universities? In this context, creativity is understood as a key competence for sustainable development, enabling individuals to solve complex problems and adapt to changing social, environmental, and economic conditions.

Although creativity is widely foregrounded in EU/UNESCO policy and the ESD literature, empirical evidence profiling the multi-component creative competence of Polish pre-service teachers—measured with SD-aligned indicators and reported with baseline distributions and simple sociodemographic correlates—remains scarce. Prior work tends to examine general student populations or in-service teachers, or treats creativity as a global trait rather than an operational competence. To address this gap, we surveyed 406 teaching candidates from Kraków universities with a 49-item instrument capturing, among others, reflexivity, openness to novelty, independence, and perseverance; we report level distributions (high/medium/low) and item-level profiles, and test associations with gender, age, and place of origin.

2. Creativity Competence—An Attempt of Conceptualization

Creativity is a concept used in many scientific and practical contexts, yet its importance becomes particularly visible in education. It is creativity that enables learners and teachers to cope with situations for which there are no ready solutions, to address complex challenges, and to design novel approaches to problems that cannot be solved by routine procedures [

17]. In this sense, creative competence can be regarded as one of the essential competencies of the 21st century, supporting not only individual growth but also broader social, cultural, and environmental transformation.

One of the first systematic attempts to conceptualize creativity in psychology was offered by Joy Paul Guilford. In his pioneering research, conducted in the mid-20th century, he emphasized the role of divergent thinking, understood as the capacity to produce multiple possible answers to a problem, and to generate ideas that are both new and valuable [

18]. This perspective laid the foundation for subsequent approaches, many of which continue to highlight creativity as a resource for innovation and adaptation. Thus, it is a highly valued and desirable competency in the sustainable development model, as it allows individuals, in their daily choices, as well as policy makers, politicians, and other people who decide the shape of modern social, economic, and environmental life, to seek sustainable solutions to complex problems.

Donald McKinnon [

19] extended this view by stressing that creativity is not just problem solving, but problem solving in a new and original way. Similarly, Frank E. Williams [

20] regarded creativity as the ability to combine seemingly unrelated pieces of information, integrate them into new structures, and link them with previous experiences to form unique solutions. Such approaches underline that creativity is more than inspiration—it is a skill, a set of competences that can be nurtured, trained, and applied across domains. Understood in this way, creativity is the foundation for core competencies in the context of sustainability. In the context of sustainable development, these definitions acquire special significance. The pressing challenges of climate change, the depletion of natural resources, or the widening gap of social inequality demand solutions that transcend conventional patterns of thought. Creativity becomes here not an optional attribute, but a key condition for responsible action. International policy documents such as Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives [

21] explicitly identify creativity as one of the core competencies that support transformative learning and the ability to co-create more sustainable societies. Creative competence, in this light, empowers not only individuals in their everyday decisions but also policy makers, educators, and institutions to design responses that integrate environmental, social, and economic concerns.

The dynamic perspective on creativity was further advanced by Ellis Paul Torrance [

22], who described it as a process of problem sensitivity: recognizing deficiencies, formulating hypotheses, and testing and revising them. In this view, creativity is crucial already at the stage of noticing problems, long before solutions are proposed. Such a perspective resonates strongly with the objectives of education for sustainable development (ESD), which is not about delivering a fixed body of knowledge but about equipping learners with competencies to navigate uncertainty and change.

In the context of sustainable education, creativity in this view supports the following:

Systems thinking, needed to understand interconnectedness in ecosystems and societies;

Decision-making under conditions of incomplete information—which is the norm in climate, social, or economic issues;

Innovative solutions to problems that do not have ready answers (e.g., how to reconcile economic development with environmental protection?);

Reflexivity and learning from mistakes, which promotes the development of responsible and adaptive attitudes.

The systemic perspective developed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi [

23] adds yet another dimension to this discussion. He argued that creativity is not solely an individual trait but rather the outcome of interaction between three elements: the person (with their cognitive and emotional capacities, motivation, and skills), the field (a domain of knowledge and practice, such as mathematics, art, or pedagogy), and the social environment (communities that evaluate and validate innovation). From this standpoint, creativity becomes a systemic competence. It requires both the ability to generate new ideas and the recognition by a given social context that these ideas are valuable. This approach fits particularly well with the logic of sustainable development, which depends not only on technological or pedagogical innovation but also on social acceptance, ethical legitimacy, and cultural embedding. A sustainable innovation is meaningful only when it is acknowledged and supported by relevant communities—schools, local governments, or global organizations.

Seen in this way, creativity contributes directly to several competencies that are vital for sustainability. First, it supports systems thinking, enabling learners to perceive interconnections between ecological, social, and economic processes. Second, it strengthens decision-making under uncertainty, a competence indispensable when acting in contexts of incomplete knowledge, as is the case with climate or social issues. Third, it fosters the capacity to design innovative solutions that reconcile seemingly contradictory goals; for example, economic growth and environmental protection. Finally, creativity develops reflexivity, understood as the ability to learn from one’s own and others’ mistakes, which in turn cultivates adaptive and responsible attitudes.

For these reasons, creativity should not be seen as a mere supplement to education but rather as a fundamental condition for preparing citizens capable of co-shaping a sustainable future. Teachers, therefore, are not only responsible for showing students “how to solve a problem” but also—and perhaps more importantly—“how to recognize that a problem exists,” which is the indispensable starting point in addressing global challenges. In Csikszentmihalyi’s systemic view, creativity is not just a characteristic of an individual, but results from the interaction of three elements:

The person—with their cognitive abilities, emotional abilities, and creative motivation;

The field—the system of knowledge and symbols (e.g., mathematics, art) within which the innovation arises;

The social environment—which evaluates whether an innovation is valuable and deserves recognition.

This approach resonates with the idea of education for sustainable development, as it captures creativity as a systemic competence, while sustainable development requires systems thinking—understanding the complex relationships between humans, society, and the environment. Creativity in this context is not just about generating ideas but about creating innovations that are embedded in social and cultural contexts, while responding to global challenges. In addition, Csikszentmihaly emphasizes the social value of innovation, and sustainable activities only make sense when they are recognized and supported by communities (e.g., schools, cities, governments). Csikszentmihalyi’s approach also takes into account that change must be socially acceptable and meaningful—and this approach corresponds with the tenets of sustainable development and the principles of education for sustainable development. In addition, personal motivation and its systemic relevance are important in this concept of creativity—and it needs to be stressed that the pursuit of sustainability requires both individual commitment (attitudes, values, competencies) and action in institutional and cultural structures—which the systemic approach reflects perfectly.

To summarize, creativity is widely recognized as a key competence for sustainability [

24,

25]. Competencies for sustainability are defined as distinctive, multifunctional, and interrelated sets of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable effective action in complex contexts [

26]. In contemporary societies facing globalization, rapid technological change, and ecological threats, these competencies are gaining unprecedented significance [

27,

28]. Within this framework, creativity, understood in line with Csikszentmihalyi’s systemic approach, becomes indispensable: it is the ability to generate and implement innovative solutions that are both socially relevant and embedded in cultural and institutional structures. Developing such competence allows individuals and societies to respond flexibly to uncertainty, to integrate diverse forms of knowledge, and to act responsibly toward both present and future generations.

Thus, nurturing creativity is not only a contribution to individual growth but also a key prerequisite for building more just, resilient, and sustainable societies.

4. Results of the Research

Creativity is described as a key competence for the transformation of the modern development model towards sustainable development [

34,

35]. The level of creative competence of teachers can significantly affect the development of this competence among students [

26]. Therefore, it is very important what level of creativity is represented by teachers, as well as those who have taken up teacher education and will work with children and young people in the future and develop their creative competencies.

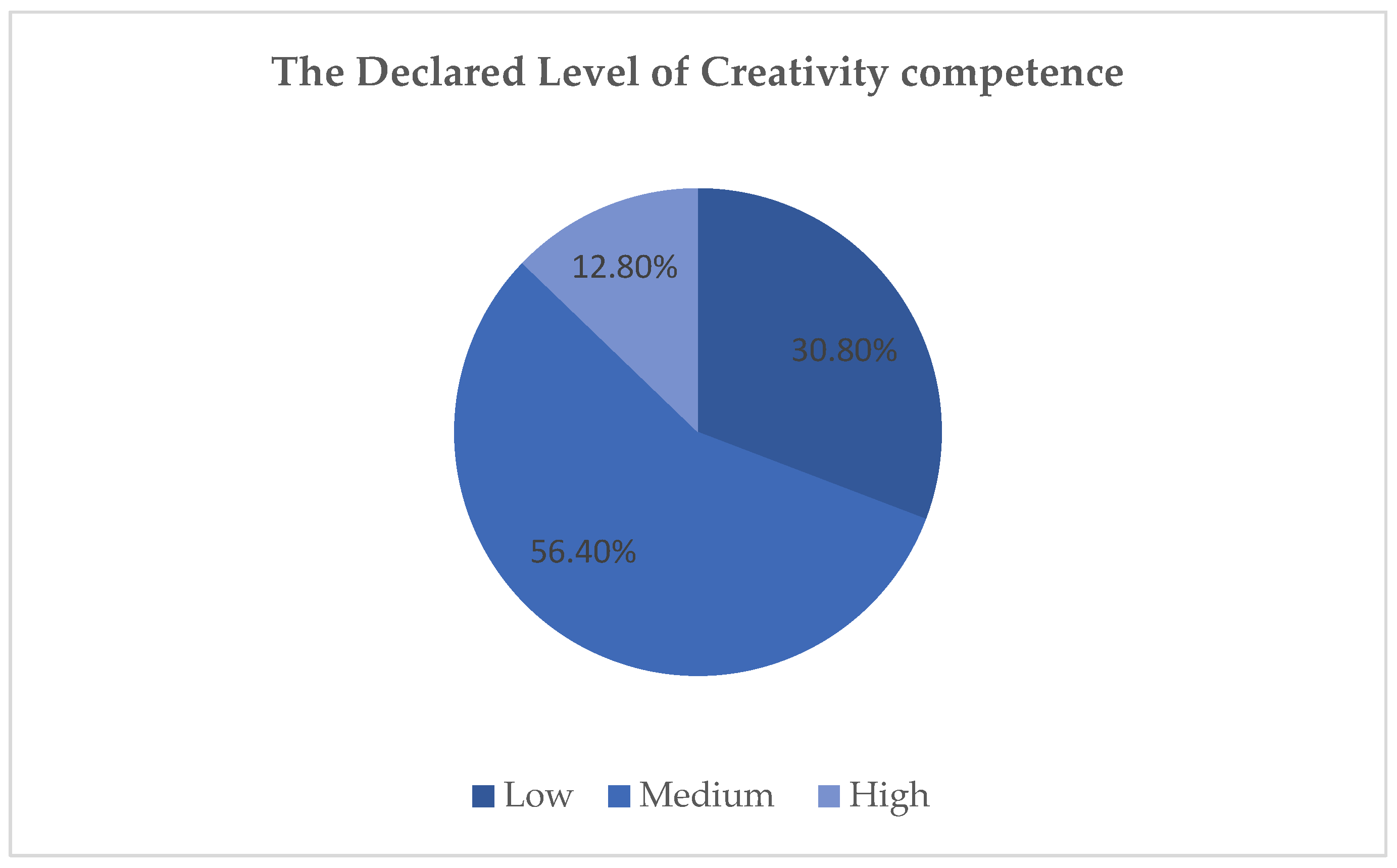

The analysis of the survey results showed that among the respondents, a high level was reached by 52 people, accounting for 12.8% of the respondents. A medium level was reached by 229 people—56.4% of respondents. In turn, a low level characterized 125 people (30.8% of respondents) (see

Figure 1).

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for the seven creativity dimensions. The highest score was obtained in metacognition and perspective-taking (M = 4.40, SD = 0.76), followed by openness and learning drive (M = 4.58, SD = 0.60). The lowest results appeared in creative production (M = 3.73, SD = 1.01) and aesthetic sensitivity (M = 3.70, SD = 0.74).

The relationships between the highlighted independent variables and the declared level of creativity competence (treated as the dependent variable) were examined (see

Table 3 and

Table 4).

As the analysis of the study shows, gender and age are practically unrelated to the declared level of creativity. Place of origin has a minimally positive correlation—people from larger towns and cities may be slightly more likely to score higher, but the relationship is very weak.

It is worth analyzing how the respondents’ answers to the various questions in the questionnaire are distributed.

Analysis of the results shows that only one in five (19.9%) of the respondents is definitely confident that they can predict the effect of the tasks/activities they undertake (M = 4.191; SD = 0.543). At the same time, almost all respondents consider themselves to be reflective (36.4% of “rather yes” and 51.7% of “definitely yes” responses; M = 4.402; SD = 0.758). These results reveal an interesting dichotomy between perceived reflexivity and a sense of confidence in predicting the effects of one’s own actions. On the one hand, the vast majority of future teachers perceive themselves as reflective, which is a positive sign in the context of creativity competence. This is because reflexivity promotes critical analysis of situations, seeing alternative possibilities and learning from experience—important elements of creative thinking [

35]. On the other hand, the relatively low level of confidence in predicting the consequences of one’s own actions may indicate a lack of confidence in one’s own competence or a fear of risk, which often accompanies the creative process. Creativity, especially in the context of education, requires not only reflection, but also a willingness to act under uncertainty, experiment, and accept potential failures [

36]. These results may therefore suggest the need to develop not only reflective abilities in future teachers, but also greater confidence in creative initiatives and acceptance of the unpredictability that often accompanies innovative activities.

Encouragingly, respondents most often declare that they like solving problems independently (46% “Rather yes” and 39.9% “Definitely yes”; M = 4.216; SD = 0.887). Self-reliance in problem solving is an important characteristic that fosters the development and use of creativity competence, especially in the teaching profession. The willingness of the majority of respondents to face challenges independently, as declared by the majority of respondents, may indicate an openness to finding one’s own solutions, experimenting and making decisions in ambiguous situations. Self-reliance is closely related to cognitive autonomy and flexibility of thinking—key components of a creative approach to problems [

35]. In the context of a teacher’s work, independence in problem-solving can translate into a greater willingness to create innovative methods of working with students, adapt activities to changing conditions, and make decisions based on one’s own thoughts rather than simply reproducing ready-made schemes. Moreover, independent problem-solving is often associated with greater satisfaction and commitment, which in turn foster creativity in action.

A total of almost three-quarters of the students who took part in the survey (48.5% “Rather yes” and 23.3% “Definitely yes”) are able to quickly find their way in a surprise situation (M = 3.778; SD = 1.013). Almost all future teachers declare that they like to learn new things (51.8% strongly agree, 36.6% rather agree; M = 4.578; SD = 0.604). These results allow a positive assessment of the creative potential of future teachers. The ability to quickly find themselves in situations of surprise and openness to new information are key elements that foster creativity and innovative approaches to teaching. The ability to adapt to unexpected circumstances, collectively declared by almost three-quarters of respondents, indicates cognitive flexibility, which is essential in a dynamic and unpredictable educational environment [

36,

37,

38]. At the same time, the almost universal declaration of a love of acquiring new information suggests a high level of cognitive curiosity—a trait considered one of the foundations of creativity. People who are curious about the world are more likely to explore new ideas, take on intellectual challenges, and are more likely to solve problems creatively [

39]. In the context of teacher education, this means that there is a solid foundation for developing creativity competence, which are based on flexibility and the constant pursuit of expanding knowledge. However, it is worth emphasizing that this potential should be consciously supported and developed in the process of education for the teaching profession, so that the declared attitudes are translated into real actions in professional practice.

Students’ answers to the question about repetitive behaviour and patterns, something that contradicts creativity, are disturbing. Only 13.7% of respondents strongly agree, while 37.4% tend to agree that replicating the same patterns and behaviours is something which does not characterize them (M = 2.926; SD = 1.234). This is worrisome, since one of the foundations of creativity is precisely the ability to go beyond the usual patterns and see alternative ways of doing things [

39]. In preparing for the teaching profession at university, it is crucial to develop flexibility of thinking and readiness to break patterns, as these are the competencies that allow teachers to respond effectively to the diverse needs of students and dynamic changes in the school environment. Schematic thinking, while often providing a sense of security and predictability, can limit the ability to be innovative in teaching and problem-solving. For this reason, it is worth fostering attitudes in future teachers that promote openness to new solutions and experimentation [

40].

Only about one in five respondents (17.9%) strongly disagree that during a discussion they ultimately agree with the interlocutor, even though they are not convinced by their arguments (41.1% rather disagree with this statement; M = 2.435; SD = 1.19). Among prospective teachers, about one in three (35.2%) strongly consider themselves persistent (M = 4.081; SD = 1.006). Nearly half declare that they are rather persistent. One in five respondents are convinced that they rarely succeed in achieving their goals (19.9% of the “definitely not” responses in the statement: “I rarely succeed in achieving my goals”; M = 2.262; SD = 1.109).

The relatively low willingness to conform uncritically to the opinions of others may indicate a certain level of independent thinking—one of the foundations of creativity. At the same time, however, the moderate self-assessment of persistence and the belief of some of the respondents that it is difficult to achieve goals may suggest limitations in the competencies associated with bringing one’s own ideas and initiatives to completion—an equally important element of the creative process. In the context of developing key competencies for sustainable development, creativity should not only be seen as the ability to generate new ideas, but also as the ability to consistently strive to implement innovative solutions for a better, more sustainable world [

22,

24]. Resilience to social pressure, perseverance, and the ability to achieve goals are qualities necessary in the process of creatively solving complex environmental and social problems. Accordingly, developing creativity in future teachers, understood as a core competence for sustainable development, should include not only shaping the ability to generate new ideas, but also building an attitude of commitment, perseverance, and critical thinking that enable effective positive change in various educational and social contexts.

Student-candidates for the teaching profession most often declare that they like meeting new people and making new friends (rather yes—32.8% rather yes and 27.6% definitely yes; M = 3.791; SD = 1.255). It is worth noting that openness to other people is associated with a willingness to explore new perspectives, accept different points of view, and participate in a variety of social experiences. This, in turn, can stimulate creativity competence, fostering the generation of original ideas and solutions. The literature on creativity often emphasizes that the ability to establish relationships and collaborate is an important component of creative performance, especially in educational environments where teamwork, exchange of ideas, and flexibility of thinking are key [

41,

42]. Surprisingly, only 6.4% of the participating teacher candidates strongly disagree with the statement that they prefer to follow a pattern (reversed question; M = 2.926; SD = 1.234). Only about a third of persons surveyed (33%) tend not to follow a scheme (M = 3.521; SD = 1.306). This result may raise some concerns in the context of shaping and using creativity competence in teachers’ work. A relatively small percentage of respondents strongly rejects following blueprints, which may indicate a tendency to follow established, safe solutions and a preference for familiar and predictable ways of doing things. Although about a third of the survey participants declare that they are unlikely to follow ready-made solutions, this result still suggests a fairly moderate openness to thinking outside the box and experimenting. The literature addressing creativity emphasizes that moving away from schematic patterns of thinking and a willingness to explore alternative paths and solutions are key elements of a creative approach to reality, especially in education. A creative teacher should not only be open to new ideas, but also capable of implementing them and modifying existing patterns [

43]. In light of these results, it is worth considering strengthening elements in teacher education that develop cognitive flexibility and courage to make creative decisions.

4.1. Gender of Respondents and Creativity Competence

Statistical analysis showed that there are some significant differences between the responses of men and women (see

Table 5). For example, “I often watch TV in my free time, I have favourite series, entertainment programs” (

p = 0.006; mean score for women: 3.43; mean score for men: 2.77). Women are more likely than men to declare that they watch TV in their free time. The difference is noticeable at the level of average scores (women rate themselves higher). Another statement, which is an element of creativity competence, against which responses differed in relation to the gender of respondents, is “I think it is important to check information about the world and compare it, using different sources”—men and women have different levels of agreement with this reflexive attitude (

p = 0.008). Men are more likely than women to agree with this statement—their average score is higher (women’s average score: 4.32; men’s average score: 4.64).

Indications towards the statement “I believe that I am creative/a” also differed by the gender of the respondents—differences in self-assessment of creativity were gender-dependent (p = 0.010) (mean score of women: 3.78; mean score of men: 3.80). Surprisingly, men consider themselves more creative than women (although the difference is minimal). Considering the statement “I like to surround myself with unique, original objects,” the difference is p = 0.013. Thus, the study confirms that aesthetic preferences and sense of originality differ between the sexes. Aesthetic preferences, as expected, stack up in favour of women (mean score for women: 3.76; mean score for men: 3.62). This means that women are slightly more likely than men to declare that they like to surround themselves with unique, original objects. For the statement “I don’t like to conform to others” (p = 0.021) there are also differences. Women have an average score of 4.15, while men have an average score of 4.11. So, slightly more often, men participating in the survey are willing to submit to others.

Also, the style of self-expression through clothing differs between men and women (p = 0.029). For the statement “I like to emphasize my uniqueness with my clothes,” the average score for women is 3.06, and for men is 2.80. Women are more likely than men to declare that they like to emphasize their uniqueness with their clothes. The difference is moderate. In addition, men are slightly more likely than women to declare that they try to look at a problem from different perspectives (p = 0.037; mean score for women: 4.30; mean score for men: 4.44). The survey also revealed differences in thinking styles and approaches to problems. Men are slightly more likely than women to report that they are able to quickly find themselves in a surprise situation (p = 0.042; mean score for women: 3.72; mean score for men: 3.95). So, men and women rate their flexibility in new situations differently.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that women are more likely than men to declare that they watch TV in their free time, and are slightly more likely to emphasize their aesthetic preferences and originality through objects or clothing. A high sense of aesthetics and the need for expression through appearance can be interpreted as elements of a creative personality, related to the search for originality and individuality—qualities essential for creativity. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to report a reflective attitude toward information (they are more likely to check and compare sources), a slightly higher self-esteem of creativity, and a greater tendency to look at problems from different perspectives and to cope better with surprise situations. These traits can also be seen as manifestations of creative competence, especially in the context of cognitive flexibility and critical thinking. In the context of developing creativity as a key competence for sustainable development, the observed differences suggest that both women and men have different but equally important resources to support the creative process. Indeed, contemporary challenges—such as climate change, social crises, and digital transformation—require not only creative generation of innovative ideas, but also critical thinking, reflection, adaptability, and perseverance. It is crucial, therefore, that teacher education reinforces all these elements, regardless of gender, developing diverse forms of creativity and related competencies. Sustainability is based on a diversity of approaches and perspectives, which is why it is so important that both women and men feel competent, supported, and inspired to act creatively for the common good. Taking gender differences into account in the design of teacher education programs can foster a fuller realization of the potential of both groups and a more effective formation of pro-sustainability attitudes in future generations. The cited results correspond with those obtained by Baer and Kaufman [

44].

4.2. Residence of Respondents vs. Creativity Competence

Table 6 shows the declared level of the creativity competence according to the place where respondents live. Although the survey did not observe statistically significant differences in the distribution of the level of creativity according to place of origin (

p = 0.272), considering individual statements, statistically significant differences were observed for some of the 49 statements included in the questionnaire, taking into account the respondents’ place of origin. For example, for the phrase:

“I devote time to creating (e.g., blog, crafts, music, poetry…)” p = 0.0067, an analysis of the mean responses shows that people from large cities are significantly more likely to declare creative activities than those from rural areas. For the statement “I prefer to follow a pattern” (reversed question),

p = 0.0120. Averages indicate that people from large cities are more likely to follow a pattern than people from rural areas. Analyzing the statement “I like to surround myself with unique, original objects,” it was noted that

p = 0.0081, so there is a statistically significant difference between the indications in this question and place of origin. The survey also revealed that students/future teachers residing in small towns declare that they are more sensitive to art (

p = 0.0089; mean scores: small town-3.15, large town-2.96, rural-2.71). Also, the ability to interpret art, a key skill for creativity, is dependent on the place of origin (

p = 0.0150). Residents of large cities fared best in this regard, with a mean of 2.90 (residents of small towns-2.74; rural areas-2.54). People from large cities are clearly more likely to declare that clothing is a way for them to emphasize uniqueness, compared to residents of rural areas and small cities (for this statement,

p = 0.0165; mean large city-2.29; small city-1.98; rural area-1.82).

Analysis of the results revealed that the respondents’ place of origin significantly differentiates some attitudes, preferences, and statements related to creativity. People living in large cities are significantly more likely to engage in creative activities such as blogging, handicrafts, music, or poetry, which may be due to greater access to cultural stimuli, resources, and opportunities to develop interests. At the same time, residents of large cities are more likely to report schematic activity, which may reflect the fast pace of life, greater social pressures, or the need to function according to certain rules and schedules. This peculiar paradox underscores the complexity of the relationship between living environment and creative attitudes. In contrast, people from small cities show higher sensitivity to art, which may suggest greater attentiveness to aesthetics and deeper reflection on symbolic values. Residents of large cities, on the other hand, fare better in their ability to interpret art, which may be the result of more extensive contact with diverse forms of culture. Significant differences also relate to the expression of individuality through clothing—people from large cities are much more likely to view it as a way of emphasizing their uniqueness, which may be related to greater acceptance of difference and the greater importance of visual identity in urban environments.

These results confirm that creativity—as a key competence for sustainable development—is a complex and multidimensional skill that is also shaped by the socio-cultural environment. The place of origin influences not only the frequency of creative activities, but also aesthetic sensitivity, reflexivity, and ways of expressing oneself. Thus, developing creativity in education—especially teacher education—should take these differences into account and strive to create equal opportunities for all, regardless of their background and cultural context.

Sustainable development requires diverse perspectives and creative solutions adapted to local conditions and challenges. The formation of creativity competence in teachers—understood as the ability to approach the world innovatively, critically, and aesthetically—is therefore fundamental to building informed, active, and open-to-change local communities.

5. Discussion of Results and Conclusions

The great challenge for today’s school as an institution is to prepare today’s students for the future; it seems an even greater challenge to realize the tenets of education for sustainable development (ESD). According to the ESD paradigm, the goal of education is to support students—who will soon be deciding what social life, the economy, and the environment will look like—in acquiring knowledge, skills, and attitudes conducive to the realization of sustainable development principles. To be active in a world whose shape is unknown today, students should possess competencies known as key competencies/core competencies for sustainability. These competencies should be developed within the framework of formal education at each stage of education, adequate to the psychophysical development of students, to the fullest extent possible in every school around the world. According to ESD, the task of teachers—who are change agents [

26]—is to support students in acquiring and developing (shaping) key competencies for sustainable development.

The results confirm that demographic variables, such as gender and age, have no significant relationship with the level of declared creativity of future teachers. This is because creativity is a competence that can develop independently of these characteristics, and its key components—such as openness, reflectiveness, cognitive curiosity, and flexibility—are largely the result of the educational environment, experiences, and individual attitudes [

45]. In turn, the weak, though noticeable, positive correlation between place of origin and creativity suggests that access to cultural and educational resources, which tends to be greater in large cities, may be somewhat conducive to creative endeavours. As Amabile [

45] emphasizes, creativity is shaped not only by individual abilities but also by the social and environmental context in which learning occurs. That is why it was so important in our study to determine whether place of origin determines the declared level of creativity competence.

Importantly, the results show high levels of declared reflexivity among prospective teachers. Reflexivity—understood as the ability to analyze one’s own actions and their consequences—plays a key role in the creative process, as it enables a critical approach to routine patterns and opens the way to finding innovative solutions [

34]. At the same time, a low level of confidence in predicting the effects of one’s own actions reveals a barrier that can limit the implementation of creative ideas. As Kember and coworkers note [

36], creativity is not only about generating ideas, but also about having the courage to implement them despite uncertainty and the risk of error. Therefore, teacher education should emphasize building not only reflexivity, but also the confidence and resilience to failure inherent in innovation. There is optimism in the fact that the majority of respondents report self-reliance in problem solving. This self-reliance, which is strongly linked to autonomy and intrinsic motivation [

39], is an important foundation for developing creativity competence. It has been repeatedly emphasized in the literature that people with high levels of cognitive autonomy are more likely to take on non-standard challenges and generate original ideas [

45]. In the context of education for sustainable development, such autonomy acquires an even broader significance: it enables individuals not only to propose innovative solutions but also to critically evaluate them in terms of their social, cultural, and environmental implications. As recent studies highlight, self-directed and autonomous learners are better prepared to co-create sustainable futures, since sustainability challenges require both independence in thought and the ability to collaborate across disciplines and perspectives

One of the key findings of the analysis also confirms the high level of openness to new information and cognitive flexibility in the participating future teachers. The ability to find surprise quickly and the willingness to learn new things are qualities that strongly support creativity and allow them to cope effectively in a dynamic educational environment.

However, the results regarding the preference for schematic behaviour and replication of patterns may raise some concerns. The relatively low percentage of respondents strongly rejecting schemas indicates the need to strengthen elements in the teacher education process that promote flexibility of thinking. As Runco and Jaeger [

46] point out, creativity is based on the ability to see alternative paths and modify established patterns, which is essential in an educational environment that requires rapid adaptation of methods and approaches to individual student needs.

Persistence and independent thinking, which are revealed in respondents’ moderate self-assessment, are also key to creativity, especially in the context of competencies for sustainable development. Brundiers and colleagues [

26] emphasize that creativity in sustainability efforts requires not only innovation, but also consistency and resilience to social pressures. What is needed, therefore, is not only the development of the ability to generate ideas, but also the competencies needed to implement them effectively. Another interesting and positive aspect of the results is the respondents’ high openness to social interaction. Creativity often develops as a result of social interaction, exchange of ideas, and cooperation. The ability to establish relationships and the willingness to explore new perspectives foster creative approaches to problem solving and build innovative solutions in education.

In contrast, the relatively low willingness to move away from schematic patterns of action suggests that there is a need to foster a greater cognitive courage and acceptance of the uncertainty inherent in creativity competence in future teachers. Cropley [

43] emphasizes that creativity requires not only the ability to generate new ideas, but above all the openness to implement and experiment.

The analysis presented in the article clearly indicates the creative potential of future teachers, which, however, requires conscious and systematic support in the educational process. Developing reflexivity, flexibility, courage to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty, and readiness to experiment should become one of the key goals of teacher education—not only from the perspective of innovation in teaching work, but also in the context of the challenges of sustainable development.

It is worth adding that the results of our study indicate a trend: positive attitudes toward creativity co-occur with greater creative activity, which is also confirmed in another context—the development of entrepreneurship. In a study by Angelova et al. [

47], it was observed that positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship significantly increase students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, it should be emphasized that positive attitudes, intrinsic motivation, and inspiration are key factors that translate into undertaking creative and innovative activities, including in the academic environment, which plays an important role in supporting such activity.

To summarize, although no formal hypotheses were formulated due to the exploratory nature of this study, the analysis was guided by a general research question: What is the declared level of creativity competence among pre-service teachers, and how is it differentiated by selected socio-demographic variables? The results provide a clear answer to this question. The majority of participants demonstrated an average level of creativity competence, with a smaller proportion showing high scores and a substantial minority obtaining low scores. These findings confirm that the creative potential of future teachers is present, yet only partly activated. Furthermore, the analysis indicated that socio-demographic variables such as gender and age did not significantly differentiate the results, while the place of origin showed only weak tendencies. In this sense, the study fulfils the main aim of exploratory research: to map tendencies and provide an empirical basis for further hypothesis-driven investigations. Future studies, building on these results, may formulate and test specific hypotheses concerning the factors that support or inhibit the development of creativity in teacher education students.

Creativity is a key competence for sustainable development and holds a pivotal role in Education for Sustainable Development—not just as an auxiliary skill, but as a core facilitator of transformative learning. In the face of wicked, interconnected global challenges—climate change, biodiversity loss, inequity—education systems must move beyond transmitting knowledge to cultivating the capacity for imaginative, flexible, and ethically grounded action.

Creativity enables learners and educators to imagine possibilities that deviate from the status quo. Sandri [

48] argues that innovation and divergent thinking are essential in envisioning and implementing alternative practices in higher education that align with sustainable pathways, enabling societies to adopt novel, context-sensitive responses. Teaching creative problem solving can deepen students’ awareness of sustainable development and lead to more engaged behaviour. For example, in a recent intervention, creative problem solving was incorporated into a master’s programme in educational management, which contributed to strengthening participants’ awareness of sustainable development [

48,

49]. A systematic review conducted by López, Vázquez-Vílchez, and Salmerón-Vílchez [

34] shows that creativity is a ubiquitous element of teaching strategies within sustainable and eco-social educational approaches. It contributes to the phases of idea generation, design, and implementation of pedagogical methods, emphasizing collaboration, reflection, and interdisciplinary learning environments.

Through creative tasks, students develop autonomy, adaptability, and reflective skills—key competences for sustainable development. The Creativity in Action project [

50] engaged students in art- or creation-based tasks to explore how creativity or art can change the way they think about sustainable development in their personal lives or communities. This project highlights how creative learning environments can support key sustainable development competencies such as systems thinking, ethical awareness, and agency.

For those reasons, the importance of creativity competence among teachers and candidates for the teaching profession is major. As transferors of competences, teachers can teach pupils attitudes and ways of dealing with uncertainty, solving complex problems, and seeking sustainable solutions in everyday life. If embraced more fully, creativity in education can help bridge theory and practice in sustainable development. It supports learners not only in having knowledge of SDGs and environmental issues but in being prepared to respond to uncertainty, to innovate, and to act locally with global awareness. The role of creativity competence of teachers and learners is crucial in this process [

51].