Multi-Species Probiotics as Sustainable Strategy to Alleviate Polyamide Microplastic-Induced Stress in Nile Tilapia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Sources of Polyamide Microplastics

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Hemato-Biochemical Parameters and Intestinal Histopathology

2.5. RNA Extraction, cDNA Preparation, and Real Time PCR Assays

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth, Survivability, and Feed Conversion Ratio

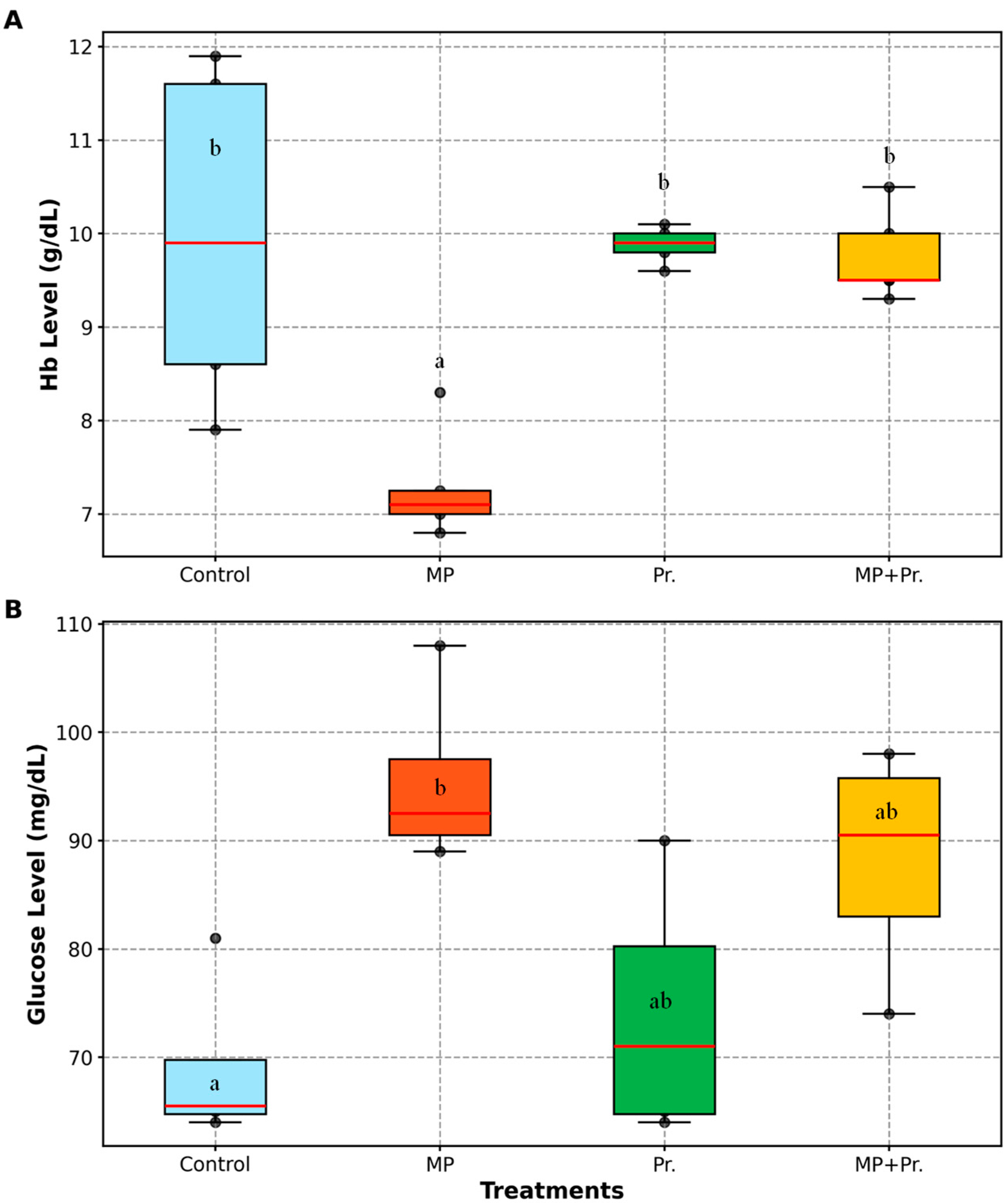

3.2. Alterations in Blood Glucose and Hemoglobin

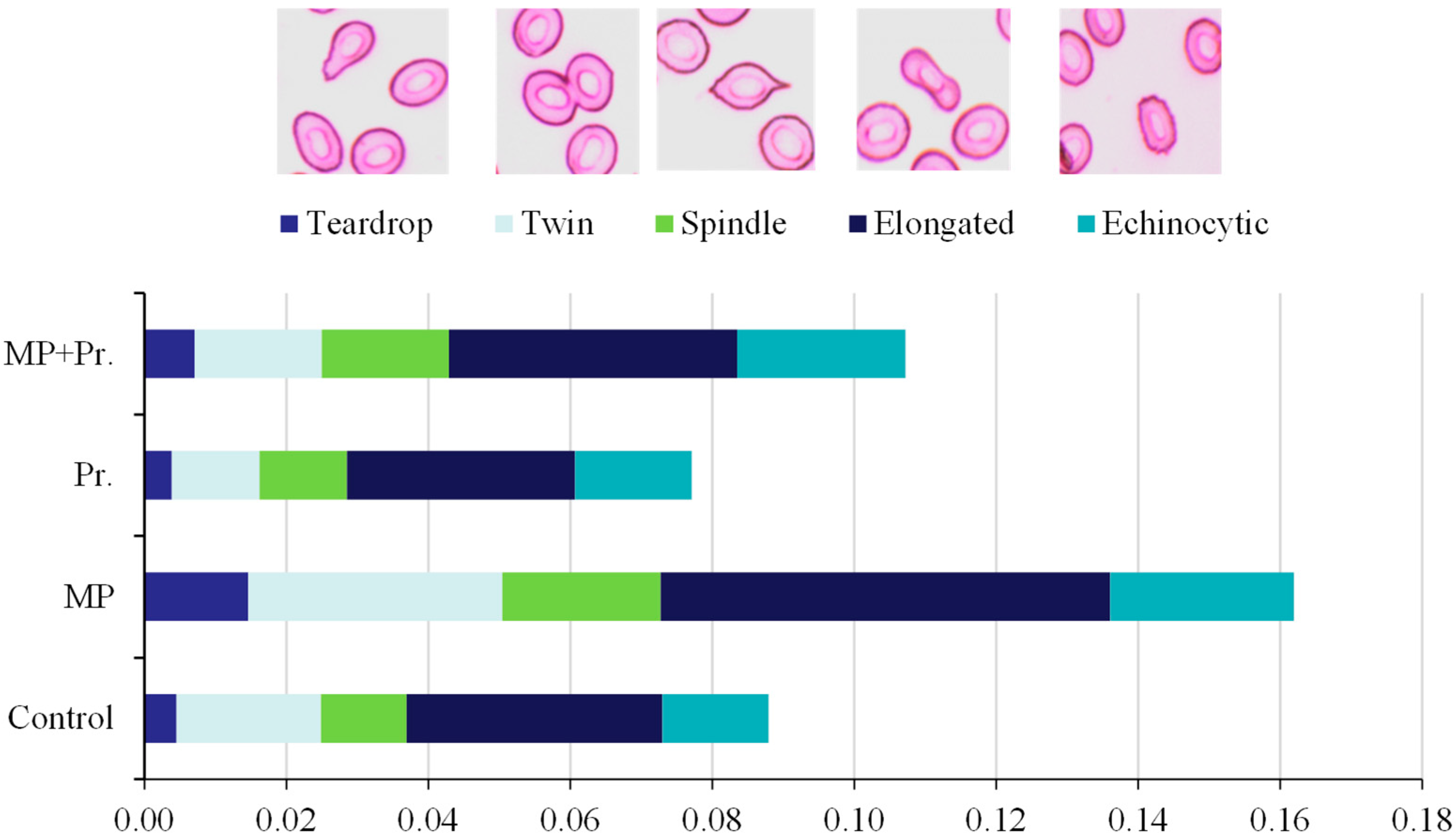

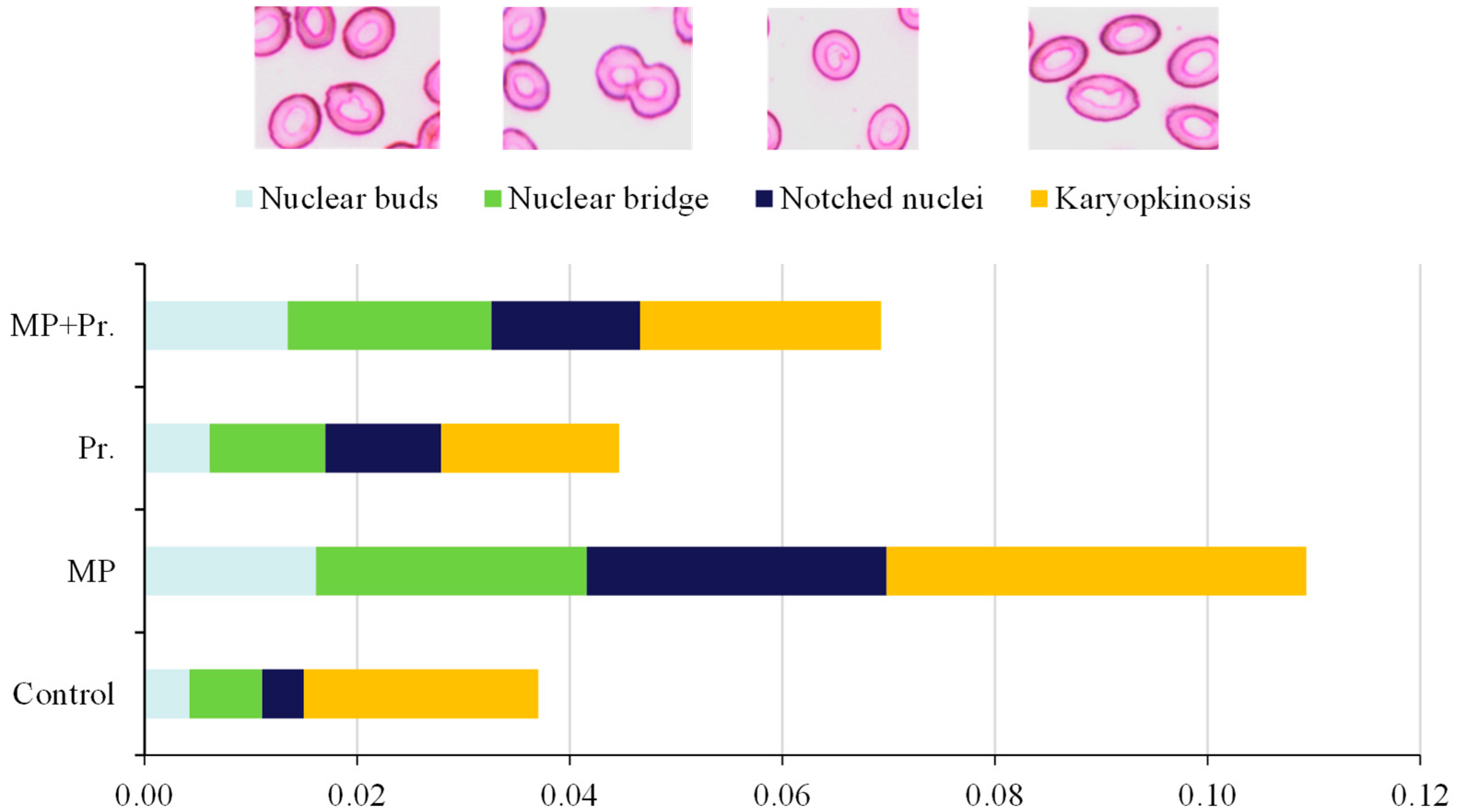

3.3. Abnormalities in Erythrocytic Cells and Nuclei

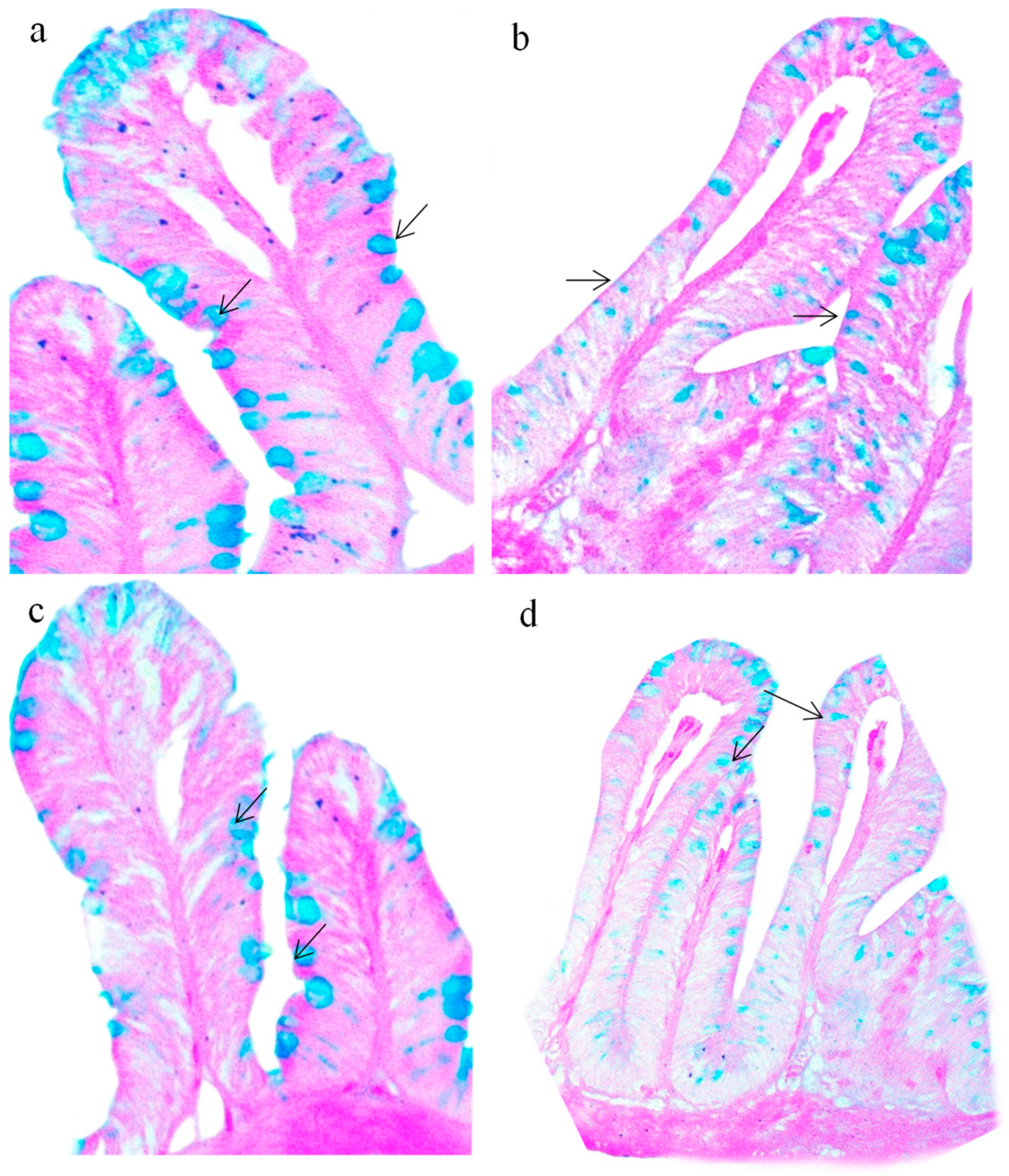

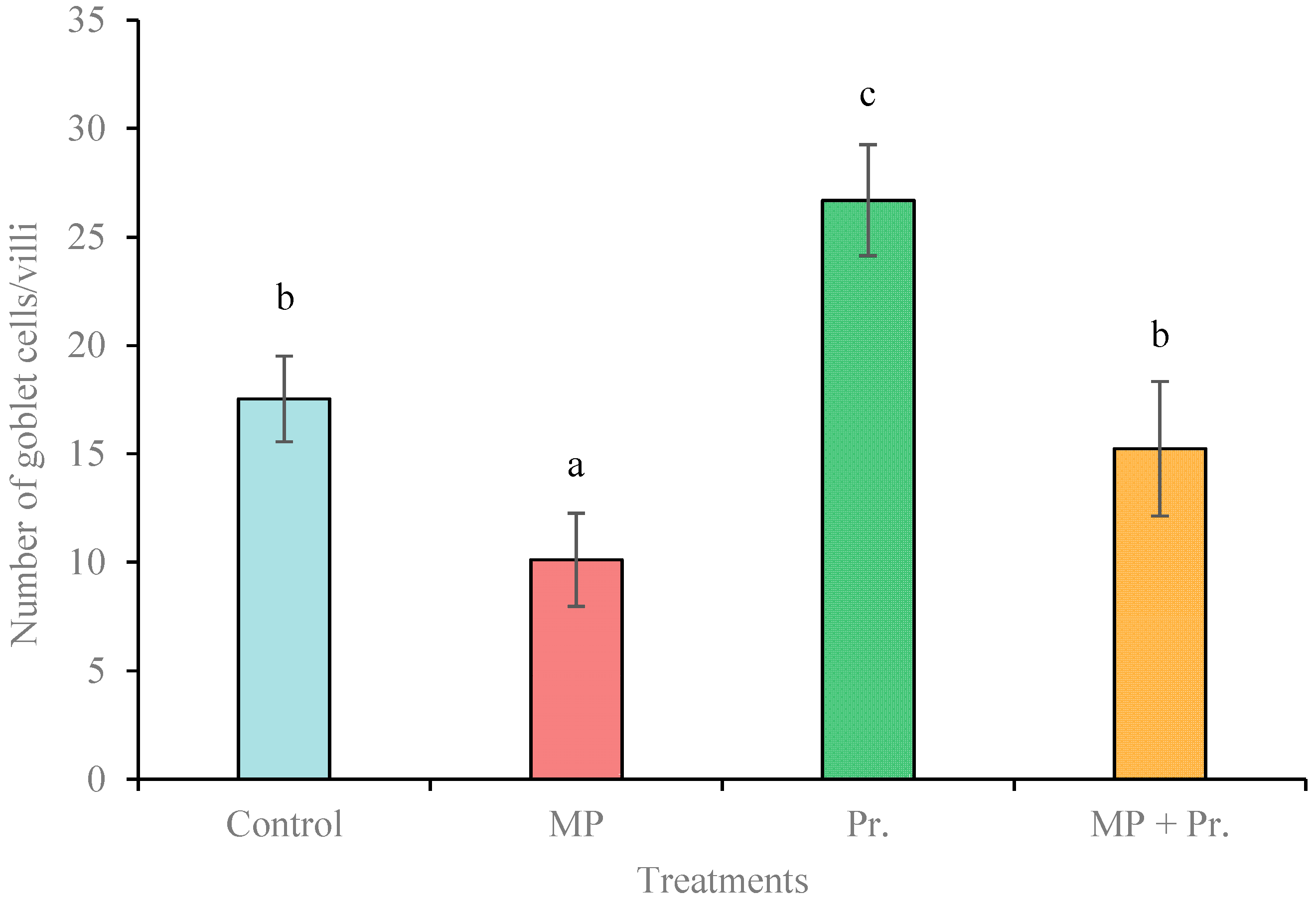

3.4. Histopathological Alterations in the Gut

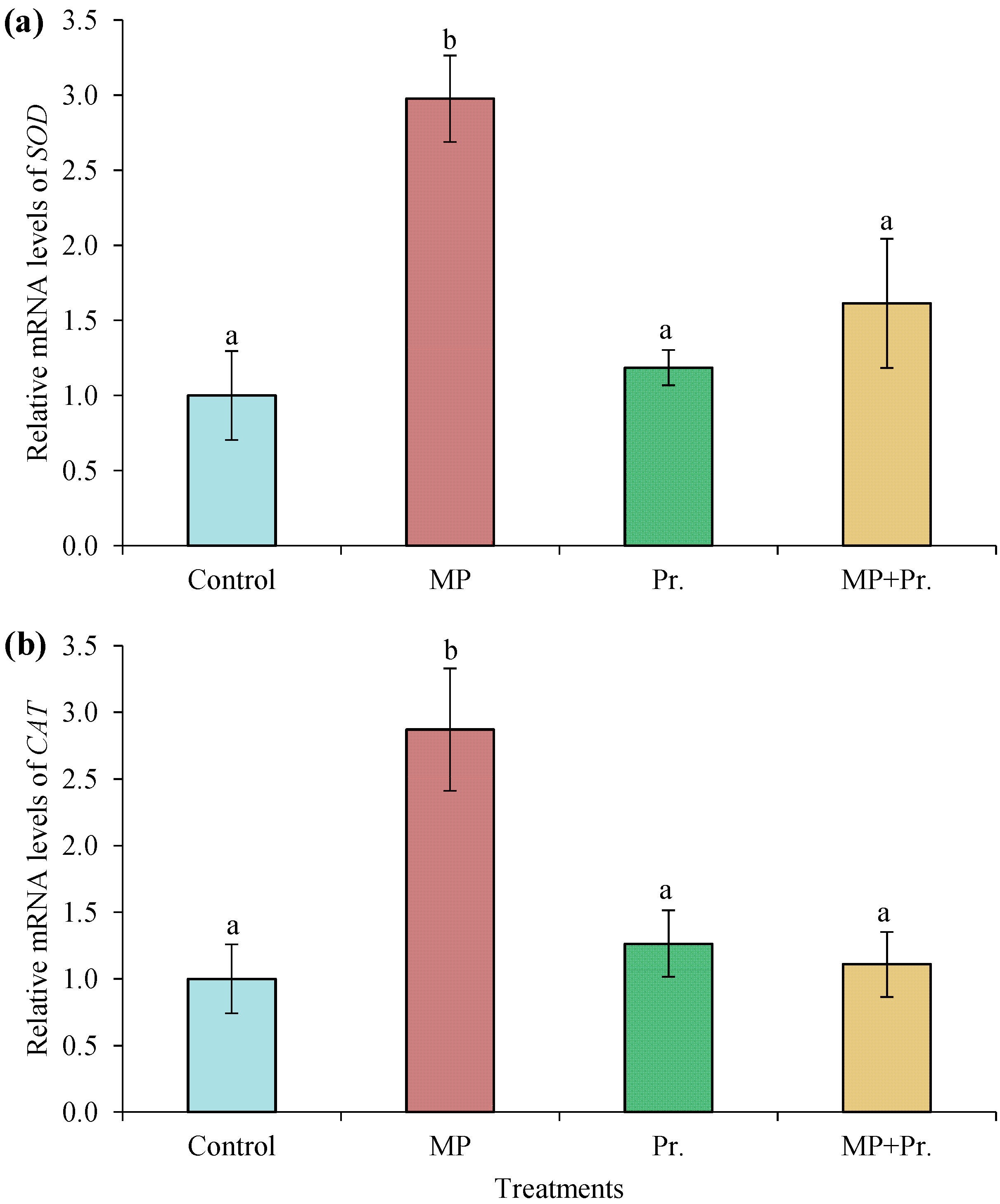

3.5. Expression of SOD and CAT Genes in Liver

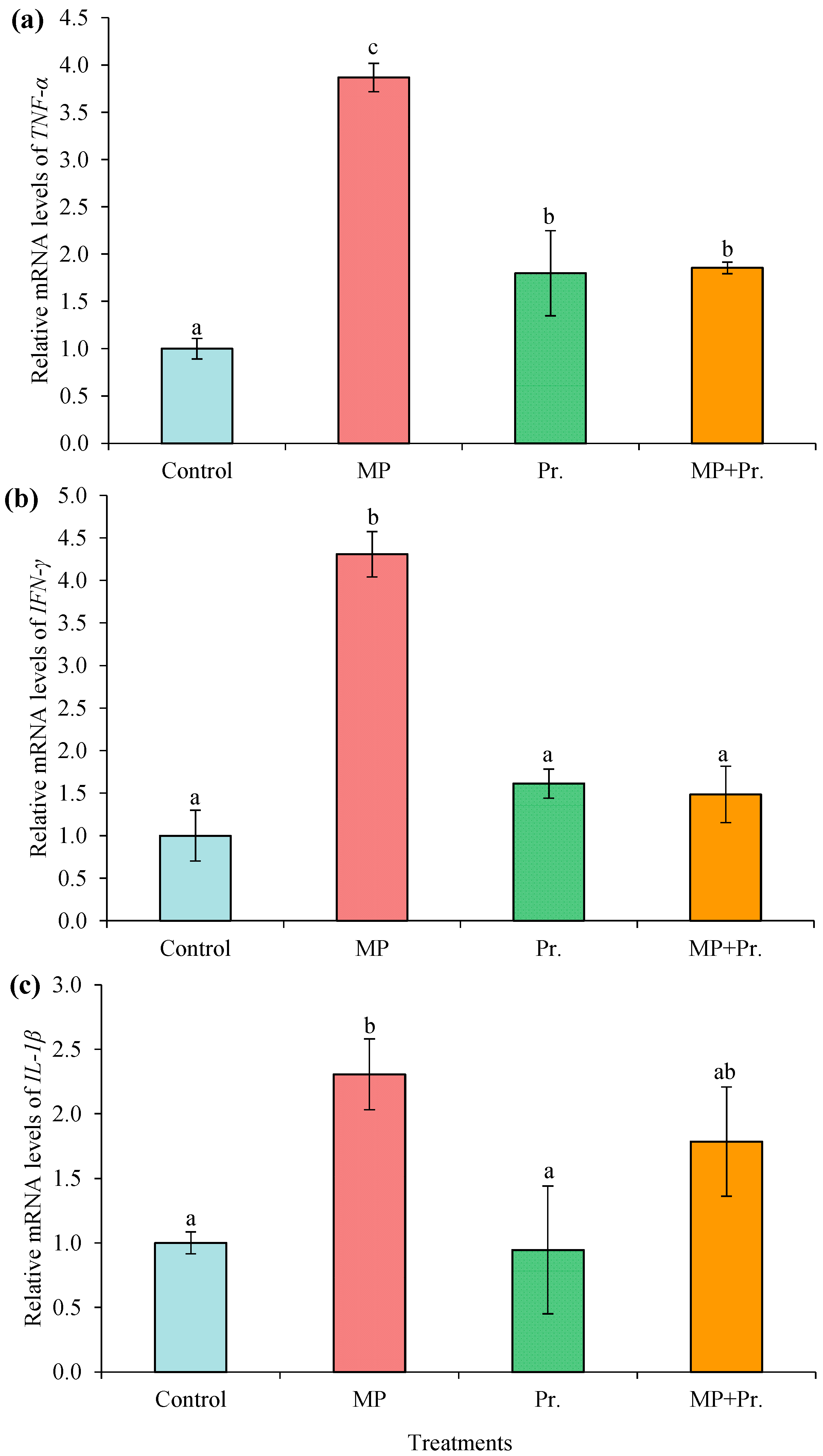

3.6. Expressions of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β in Liver

3.7. Water Quality Parameters

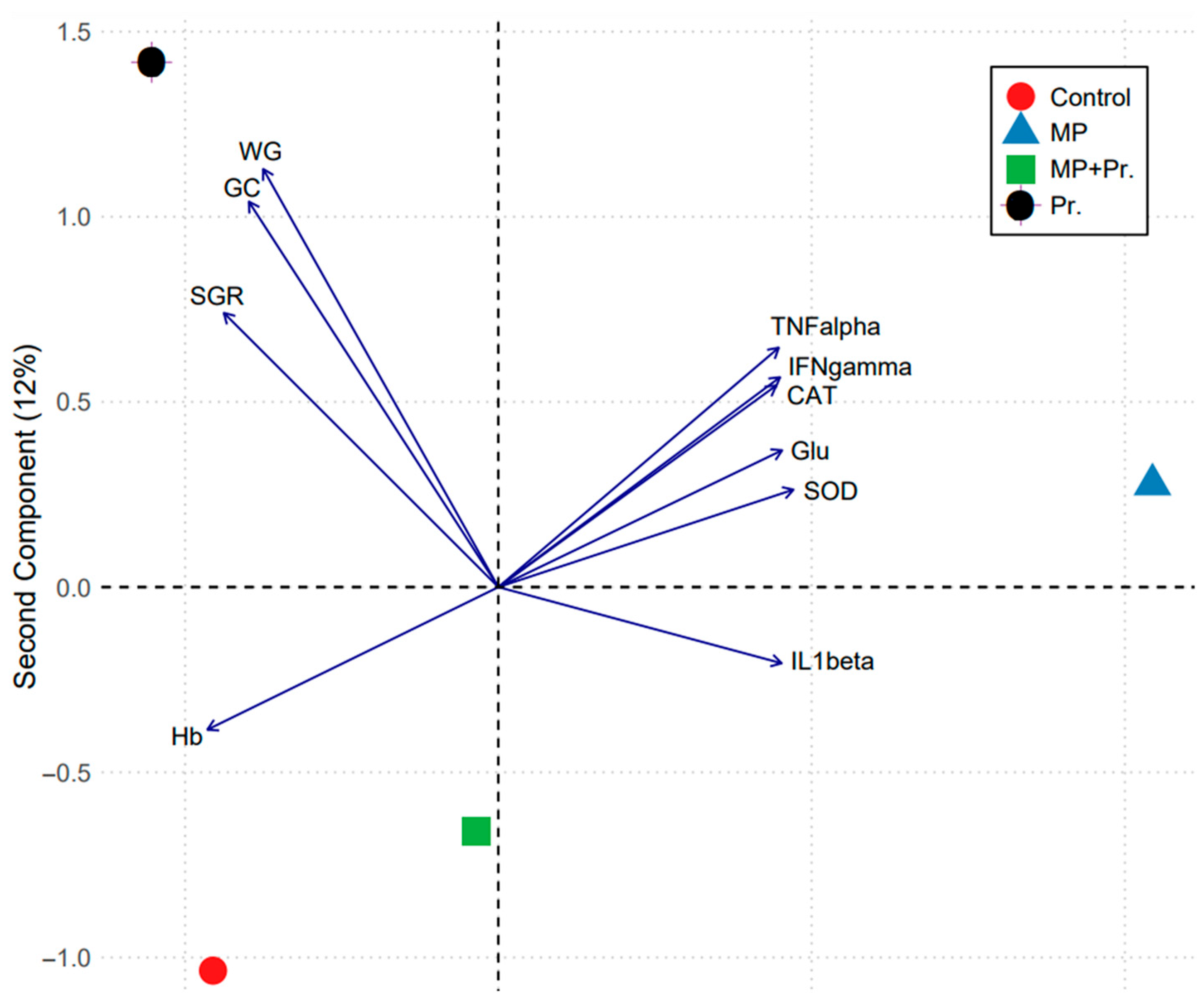

3.8. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasan, J.; Shahriar, S.I.M.; Shahjahan, M. Release of Microfibers from Surgical Face Masks: An Undesirable Contributor to Aquatic Pollution. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2023, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Sinha, J.K.; Ghosh, S.; Vashisth, K.; Han, S.; Bhaskar, R. Microplastics as an Emerging Threat to the Global Environment and Human Health. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.R.; Olden, J.D. Global Meta-Analysis Reveals Diverse Effects of Microplastics on Freshwater and Marine Fishes. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 1439–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, F.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Ai, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Microplastic on Fish: Insights into Growth, Survival, Reproduction, Oxidative Stress, and Gut Microbiota Diversity. Water Res. 2024, 267, 122493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A.; Mekonnen, B.A. Distribution and Impact of Microplastics in the Aquatic Systems: A Review of Ecotoxicological Effects on Biota. In Microplastic Pollution; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 65–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Tang, J.; Lyu, H.; Wang, L.; Gillmore, A.B.; Schaeffer, S.M. Activities of Microplastics (MPs) in Agricultural Soil: A Review of MPs Pollution from the Perspective of Agricultural Ecosystems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 4182–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, N.; Reis-Santos, P.; Gillanders, B.M. Microplastic in Fish—A Global Synthesis. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2021, 31, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, S.; Abidin, A.S.; Hikmaturrohmi, H.; Ilhami, B.T.K.; Kurniawan, N.S.H.; Jupri, A.; Candri, D.A.; Frediansyah, A.; Prasedya, E.S. Microplastic Contamination in Different Marine Species of Bintaro Fish Market, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbery, M.; O’Connor, W.; Palanisami, T. Trophic Transfer of Microplastics and Mixed Contaminants in the Marine Food Web and Implications for Human Health. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühn, S.; Van Franeker, J.A. Quantitative Overview of Marine Debris Ingested by Marine Megafauna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrovyan, A.; Gabrielyan, B.; Kahru, A. Ingestion and Effects of Virgin Polyamide Microplastics on Chironomus riparius Adult Larvae and Adult Zebrafish Danio rerio. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xia, M.; Zhao, J.; Cao, Z.; Zou, W.; Zhou, Q. Photoaging Enhanced the Adverse Effects of Polyamide Microplastics on the Growth, Intestinal Health, and Lipid Absorption in Developing Zebrafish. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klangnurak, W.; Chunniyom, S. Screening for Microplastics in Marine Fish of Thailand: The Accumulation of Microplastics in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Different Foraging Preferences. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 27161–27168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, J.; Siddik, M.A.; Ghosh, A.K.; Mesbah, S.B.; Sadat, M.A.; Shahjahan, M. Increase in Temperature Increases Ingestion and Toxicity of Polyamide Microplastics in Nile Tilapia. Chemosphere 2023, 327, 138502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahriar, S.I.M.; Islam, N.; Emon, F.J.; Ashaf-Ud-Doulah, M.; Khan, S.; Shahjahan, M. Size Dependent Ingestion and Effects of Microplastics on Survivability, Hematology and Intestinal Histopathology of Juvenile Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Chemosphere 2024, 356, 141827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, M.; Berlino, M.; Mangano, M.C.; Sarà, G. Microplastics and the Functional Traits of Fishes: A Global Meta-Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2645–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.J.; Feiner, Z.S.; Malinich, T.D.; Höök, T.O. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Exposure to Microplastics on Fish and Aquatic Invertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales-Ribeiro, D.; Brito-Casillas, Y.; Fernandez, A.; Caballero, M.J. An End to the Controversy over the Microscopic Detection and Effects of Pristine Microplastics in Fish Organs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 69062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaee, M.; Multisanti, C.R.; Impellitteri, F.; Piccione, G.; Faggio, C. Environmental Toxicology of Microplastic Particles on Fish: A Review. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 287, 110042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Kang, K. Overview of Microplastic Pollution and Its Influence on the Health of Organisms. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2023, 58, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katare, Y.; Singh, P.; Sankhla, M.S. Microplastics in Aquatic Environments: Sources, Ecotoxicity, Detection & Remediation. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 12, 3407–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchell, K.; Hoogenboom, M.O. Effects of Microplastic Exposure on the Body Condition and Behaviour of Planktivorous Reef Fish (Acanthochromis polyacanthus). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atamanalp, M.; Kokturk, M.; Kırıcı, M.; Ucar, A.; Kırıcı, M.; Parlak, V.; Aydın, A.; Alak, G. Interaction of Microplastic Presence and Oxidative Stress in Freshwater Fish: A Regional Scale Research, East Anatolia of Türkiye (Erzurum & Erzincan & Bingöl). Sustainability 2022, 14, 12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Yousefi, S.; Van Doan, H.; Ashouri, G.; Gioacchini, G.; Maradonna, F.; Carnevali, O. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense in Fish: The Implications of Probiotic, Prebiotic, and Synbiotics. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 29, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Leem, E.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, S.R. Control of Reactive Oxygen Species for the Prevention of Parkinson’s Disease: The Possible Application of Flavonoids. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiry, N.; Darvishi, P.; Gholamhossieni, A.; Pastorino, P.; Faggio, C. Exploring the Combined Interplays: Effects of Cypermethrin and Microplastic Exposure on the Survival and Antioxidant Physiology of Astacus leptodactylus. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2023, 259, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, H.; Karim, S.N.; Yahaya, N.; Syed Abd Halim, S.A.S.; Zanuari, F.I.; Yahya, H.N. Occurrence and Pathways of Microplastics, Quantification Protocol and Adverse Effects of Microplastics towards Freshwater and Seawater Biota. Food Res. 2023, 7, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Y.; Nie, L.; Zhu, G.; Xiang, L.X.; Shao, J.Z. Advances in Research of Fish Immune-Relevant Genes: A Comparative Overview of Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Teleosts. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2013, 39, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakharuthai, C.; Areechon, N.; Srisapoome, P. Molecular Characterization, Functional Analysis, and Defense Mechanisms of Two CC Chemokines in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Response to Severely Pathogenic Bacteria. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 59, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Zha, J.; Wang, G. Probiotic Potential of Bacillus velezensis JW: Antimicrobial Activity against Fish Pathogenic Bacteria and Immune Enhancement Effects on Carassius auratus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 78, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.K.; Naziat, A.; Atikullah, M.; Hasan, M.T.; Ferdous, Z.; Paray, B.A.; Zahangir, M.M.; Shahjahan, M. Probiotics Relieve Growth Retardation and Stress by Upgrading Immunity in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) during High Temperature Events. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 316, 116054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Ibáñez, A.L.; Monroy Hermosillo, O.A.; Ramírez Saad, H.C. Use of Probiotics in Aquaculture. ISRN Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 916845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Sharma, J.G.; Singh, R. Biotherapeutic Microbial Supplementation for Ameliorating Fish Health: Developing Trends in Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics Use in Finfish Aquaculture. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2022, 23, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Hossain, M.M.; Mim, Z.T.; Khatun, H.; Hossain, M.T.; Shahjahan, M. Multi-Species Probiotics Improve Growth, Intestinal Microbiota and Morphology of Indian Major Carp Mrigal Cirrhinus cirrhosus. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, M.F.; Islam, S.M.; Hossain, M.K.; Ferdous, Z.; Siddik, M.A.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Padeniya, U.; Brown, C.; Shahjahan, M. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics Improved the Functionality of Aquafeed: Upgrading Growth, Reproduction, Immunity and Disease Resistance in Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 120, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvanou, M.V.; Feidantsis, K.; Staikou, A.; Apostolidis, A.P.; Michaelidis, B.; Giantsis, I.A. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics Utilization in Crayfish Aquaculture and Factors Affecting Gut Microbiota. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdous, Z.; Rafiquzzaman, S.M.; Shahjahan, M. Probiotics Ameliorate Chromium-Induced Growth Retardation and Stress in Indian Major Carp Rohu, Labeo rohita. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannat, M.M.; Islam, N.; Rayhan, M.A.; Al Imran, A.; Nibir, S.S.; Satter, A.; Taslima, K.; Shahjahan, M. Bioremediation of Chromium-Induced Toxic Effects in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Using Probiotics. Environ. Pollut. Manag. 2024, 1, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannat, M.M.; Rohani, M.F.; Jeba, R.O.Z.; Shahjahan, M. Multi-Species Probiotics Ameliorate Salinity-Induced Growth Retardation in Striped Catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbekpornu, P.; Kevudo, I. The Risks of Microplastic Pollution in the Aquatic Ecosystem. In Advances and Challenges in Microplastics; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bao, N.; Ren, T.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Bai, Z.; Hu, Y.; Ding, J. The Effect of a Multi-Strain Probiotic on Growth Performance, Non-Specific Immune Response, and Intestinal Health of Juvenile Turbot, Scophthalmus maximus L. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 45, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqua Culture Asia Pacific. The Global Tilapia; Aqua Culture Asia Pacific: Singapore, 2025; Available online: https://aquaasiapac.com/2025/02/04/the-global-tilapia/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Quarterly Tilapia Analysis; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7e605894-bca8-42fa-abbc-d7d5890cff9b/content (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Fitzsimmons, K. From Africa to the World—The Journey of Nile Tilapia. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciravolo, D. Tilapia: Numbers, Challenges and Opportunities in World Trade. Blue Life Hub. 2025. Available online: https://www.bluelifehub.com/2025/05/06/tilapia-numbers-challenges-and-opportunities-in-world-trade/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- IMARC Group. Tilapia Market Scope & Price Insights|Forecast Report 2033; IMARC Group: Noida, India, 2025; Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/tilapia-market (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Global Growth Insights. Tilapia Market Size, Growth|Global Report [2025–2034]; Global Growth Insights: Pune, India, 2025; Available online: https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/market-reports/tilapia-market-108952 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Prabu, E.; Rajagopalsamy, C.B.T.; Ahilan, B.; Jeevagan, I.J.M.A.; Renuhadevi, M.J.A.R. Tilapia—An Excellent Candidate Species for World Aquaculture: A Review. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2019, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.L.; Shahjahan, M.; Ahmed, N. Tilapia Farming in Bangladesh: Adaptation to Climate Change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Lin, L.; Xu, P.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, C.; Ding, D.; Suo, A. Effects of Microplastic Fibers on Lates calcarifer Juveniles: Accumulation, Oxidative Stress, Intestine Microbiome Dysbiosis and Histological Damage. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emon, F.J.; Hasan, J.; Shahriar, S.I.M.; Islam, N.; Islam, M.S.; Shahjahan, M. Increased Ingestion and Toxicity of Polyamide Microplastics in Nile Tilapia with Increase of Salinity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 282, 116730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Islam, S.M.; Rafiquzzaman, S.M.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.T.; Shahjahan, M. Multi-Species Probiotics Enhance Growth of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) through Upgrading Gut, Liver and Muscle Health. Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 5710–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.A.; Batista, S.; Pires, M.A.; Silva, A.P.; Pereira, L.F.; Saavedra, M.J.; Ozório, R.O.A.; Rema, P. Dietary Probiotic Supplementation Improves Growth and the Intestinal Morphology of Nile Tilapia. Animal 2017, 11, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, S. Effects of dietary caffeic acid supplement on antioxidant, immunological and liver gene expression responses, and resistance of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus to Aeromonas veronii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 86, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahjahan, M.; Rahman, M.S.; Islam, S.M.; Uddin, M.H.; Al-Emran, M. Increase in Water Temperature Increases Acute Toxicity of Sumithion Causing Nuclear and Cellular Abnormalities in Peripheral Erythrocytes of Zebrafish Danio rerio. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 36903–36912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahjahan, M.; Uddin, M.H.; Bain, V.; Haque, M.M. Increased Water Temperature Altered Hemato-Biochemical Parameters and Structure of Peripheral Erythrocytes in Striped Catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 44, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, B. Ingestion of Microplastics by Fish and Its Potential Consequences from a Physical Perspective. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2017, 13, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.S. Effects of Microplastics on Fish and in Human Health. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 827289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Peng, R. Toxic Effects of Microplastic and Nanoplastic on the Reproduction of Teleost Fish in Aquatic Environments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 62530–62548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyea, M.M.; Benfey, T.J.; Kieffer, J.D. Hematology and Stress Physiology of Juvenile Diploid and Triploid Shortnose Sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2005, 31, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.; Osman, A.G.M.; Badrey, A.E.A.; Soliman, H.A.M.; Sayed, A.E.-D.H. Microplastics-Induced Eryptosis and Poikilocytosis in Early-Juvenile Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 742922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.; Soliman, H.A.M.; Osman, A.G.M.; Sayed, A.E.-D.H. Assessment the Effect of Exposure to Microplastics in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Early Juvenile: I. Blood Biomarkers. Chemosphere 2019, 228, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahjahan, M.; Islam, M.J.; Hossain, M.T.; Mishu, M.A.; Hasan, J.; Brown, C. Blood Biomarkers as Diagnostic Tools: An Overview of Climate-Driven Stress Responses in Fish. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 843, 156910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Ma, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Bian, X.; Zhang, N. The Role and Mechanism of Probiotics Supplementation in Blood Glucose Regulation: A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Marazzato, M.; Pensa, M.; Loverro, M.T.; Quercia, M.; Lombardi, F.; Schettini, F.; Laforgia, N. SLAB51 Multi-Strain Probiotic Formula Increases Oxygenation in Oxygen-Treated Preterm Infants. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.; Zahangir, M.M.; Jannat, R.; Hasan, M.N.; Suchana, S.A.; Rohani, M.F.; Shahjahan, M. Hypoxia Reduced Upper Thermal Limits Causing Cellular and Nuclear Abnormalities of Erythrocytes in Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 90, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, F.A.; Porcino, C.; Cerezuela, R.; Cuesta, A.; Faggio, C.; Esteban, M.A. Impact of Date Palm Fruits Extracts and Probiotic Enriched Diet on Antioxidant Status, Innate Immune Response and Immune-Related Gene Expression of European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 52, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ge, J.; Yu, X. Bioavailability and Toxicity of Microplastics to Fish Species: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancke, B.; Gaskins, H.R. Microbial Modulation of Innate Defense: Goblet Cells and the Intestinal Mucus Layer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 1131S–1141S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuckin, M.A.; Lindén, S.K.; Sutton, P.; Florin, T.H. Mucin Dynamics and Enteric Pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasco, M.; Gavaia, P.J.; Bensimon-Brito, A.; Cordelières, F.P.; Santos, T.; Martins, G.; De Castro, D.T.; Silva, N.; Cabrita, E.; Bebianno, M.J.; et al. Effects of Pristine or Contaminated Polyethylene Microplastics on Zebrafish Development. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, T.; Monjezi, N.; Peyghan, R.; Mohammadian, B. Effects of Dietary Probiotic Supplements on Growth, Digestive Enzymes Activity, Intestinal Histomorphology and Innate Immunity of Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio): A Field Study. Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standen, B.T.; Peggs, D.L.; Rawling, M.D.; Foey, A.; Davies, S.J.; Santos, G.A.; Merrifield, D.L. Dietary Administration of a Commercial Mixed-Species Probiotic Improves Growth Performance and Modulates the Intestinal Immunity of Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 49, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsaheb, M.; Hossini, H.; Makhdoumi, P. Review of Microplastic Occurrence and Toxicological Effects in Marine Environment: Experimental Evidence of Inflammation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 142, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yu, Y.B.; Choi, J.H. Toxic Effects on Bioaccumulation, Hematological Parameters, Oxidative Stress, Immune Responses and Neurotoxicity in Fish Exposed to Microplastics: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zhou, C.; Wang, S.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, Q. Probiotics Ameliorate Polyethylene Microplastics-Induced Liver Injury by Inhibition of Oxidative Stress in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 130, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, M.A.P.; Dantas, M.D.S.; Rios, C.T.; Borges, L.P.; Serafini, M.R.; Guimarães, A.G.; Walker, C.I.B. Zebrafish as a Tool for Studying Inflammation: A Systematic Review. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2022, 30, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugwanya, M.; Dawood, M.A.O.; Kimera, F.; Sewilam, H. Updating the Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics for Tilapia Aquaculture as Leading Candidates for Food Sustainability: A Review. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 130–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhulika; Ngasotter, S.; Meitei, M.M.; Kara, T.; Meinam, M.; Sharma, S.; Rathod, S.K.; Singh, S.B.; Singh, S.K.; Bhat, R.A.H. Multifaceted Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Health and Growth of Aquatic Animals: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Sustainable Aquaculture—A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Aquac. Nutr. 2025, 2025, 5746972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringø, E. Probiotics in Shellfish Aquaculture. Aquac. Fish. 2020, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, K.M.; Reda, R.M. Improvement of Immunity and Disease Resistance in the Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, by Dietary Supplementation with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 44, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, A.H.; Gouda, M.Y.; Al-Sokary, E.T.; Elseify, M.M. Lactobacillus plantarum Enhances Immunity of Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus Challenged with Edwardsiella tarda. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MP | Pr. | MP + Pr. | |

| IBW (g) | 3.50 ± 0.25 a | 3.96 ± 0.19 a | 3.96 ± 0.40 a | 3.06 ± 0.24 a |

| FBW (g) | 20.57 ± 4.76 ab | 17.90 ± 3.53 a | 27.06 ± 6.27 b | 21.20 ± 5.14 ab |

| WG (g) | 17.06 ± 4.76 b | 13.94 ± 3.53 a | 23.16 ± 6.27 c | 17.56 ± 5.14 b |

| SGR (%/day) | 2.04 ± 0.30 ab | 1.75 ± 0.24 a | 2.25 ± 0.26 b | 1.97 ± 0.27 ab |

| FCR | 0.99 ± 0.34 ab | 1.13 ± 0.33 b | 0.68 ± 0.17 a | 0.91 ± 0.26 ab |

| Survival (%) | 100 | 96 | 100 | 98 |

| Parameters | Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MP | Pr. | MP + Pr. | |

| Temperature (°C) | 31.40 ± 0.90 | 31.27 ± 0.86 | 31.23 ±0.94 | 31.68 ± 0.78 |

| pH | 8.60 ± 0.19 | 8.78 ± 0.04 | 8.54 ± 0.43 | 8.65 ± 0.17 |

| NH3 (mg/L) | 0.28 ± 0.44 | 0.39 ± 0.34 | 0.38 ± 0.14 | 0.24 ± 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amin, M.; Islam, M.S.; Sweety, M.M.A.; Islam, M.; Naziat, A.; Zahangir, M.M.; Ahmed, N.; Shahjahan, M. Multi-Species Probiotics as Sustainable Strategy to Alleviate Polyamide Microplastic-Induced Stress in Nile Tilapia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209085

Amin M, Islam MS, Sweety MMA, Islam M, Naziat A, Zahangir MM, Ahmed N, Shahjahan M. Multi-Species Probiotics as Sustainable Strategy to Alleviate Polyamide Microplastic-Induced Stress in Nile Tilapia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209085

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmin, Mahadi, Md Sameul Islam, Mst Mahfuja Akhter Sweety, Muallimul Islam, Azmaien Naziat, Md. Mahiuddin Zahangir, Nesar Ahmed, and Md Shahjahan. 2025. "Multi-Species Probiotics as Sustainable Strategy to Alleviate Polyamide Microplastic-Induced Stress in Nile Tilapia" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209085

APA StyleAmin, M., Islam, M. S., Sweety, M. M. A., Islam, M., Naziat, A., Zahangir, M. M., Ahmed, N., & Shahjahan, M. (2025). Multi-Species Probiotics as Sustainable Strategy to Alleviate Polyamide Microplastic-Induced Stress in Nile Tilapia. Sustainability, 17(20), 9085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209085