Abstract

Persistent regional imbalances and widening urban–rural income gaps hinder progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 10 (Reduced Inequalities). In response, China has implemented a typical regional cooperation program—East–West Cooperation (EWC). Using a balanced panel of 642 western counties from 2013 to 2020 and the staggered difference-in-differences (DIDs) model, we assess the impact of EWC on the urban–rural income gap. We show that EWC narrows the urban–rural income gap, primarily by increasing rural incomes rather than changing urban incomes. Mechanism analyses indicate that expanded rural employment and higher agricultural production efficiency are the principal channels. The greater the economic disparity and the shorter the distance between paired counties, the stronger the effect of EWC. This effect is particularly pronounced in southwestern assisted counties and in agriculture-intensive assisted counties. The above evidence suggests that horizontal regional cooperation can deliver equity-enhancing growth. Policy should prioritize rural-first resource allocation, employment-oriented labor cooperation, and agricultural upgrading, while refining pairing rules to account for the magnitude of economic gaps and geographic proximity.

1. Introduction

Regional development imbalances and widening urban–rural income gaps remain a first-order challenge to inclusive growth and speak directly to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10 (Reduced Inequalities). These challenges are particularly acute in developing economies such as sub-Saharan Africa. In sub-Saharan Africa, recent studies document that a larger urban–rural income gap is associated with slower poverty reduction and persistent poverty trap, which underscores the policy relevance of distributionally inclusive growth in developing regions [1,2]. Among policy responses, horizontal regional cooperation has been widely adopted to mitigate spatial inequality. China’s East–West Cooperation (EWC) is a prominent, long-running program within horizontal regional cooperation. Yet it remains unclear whether such regional cooperation translates into narrowing of the urban–rural income gap, and through which channels. This evidence gap not only constrains efforts to narrow the urban–rural income gap but also results in an incomplete assessment of the distributive consequences of regional cooperation policies. Against this backdrop, it is necessary to examine the impact of regional cooperation on the urban–rural income gap.

For a long time, regional cooperation has served as a crucial policy tool for alleviating regional imbalances and regulating income distribution, becoming a focal point in global development economics and policy practice. Countries have employed diverse regional cooperation policies to reduce interregional and intra-regional income inequalities (particularly urban–rural income disparities). Existing studies coalesce around three main strands. First, the literature has established a well-developed understanding of the theoretical underpinnings and practical effects of regional cooperation. In the prior literature, regional cooperation is situated within the collaborative governance tradition as a horizontal intergovernmental arrangement that coordinates public tasks across jurisdictions and enables joint action [3,4]. The practice-oriented literature shows that cooperation pools resources and delivers shared services through intermunicipal instruments, for example, joint authorities, shared-service contracts, and pooled budgeting [5]. By contrast, market-driven integration aligns individual production factors through privatization or contracting out and is therefore analytically distinct from cooperation among public jurisdictions, because coordination occurs through markets rather than through intergovernmental institutions [6]. Similarly, municipal amalgamations are top-down boundary consolidations that restructure jurisdictions to pursue scale or administrative efficiency, but they do not cultivate voluntary horizontal cooperation [7]. Empirical studies report that cooperative regional arrangements are associated with higher economic growth, which may arise from agglomeration, specialization, and cost sharing [8], and with regional convergence in per capita outcomes across space [9,10]. However, the distributional consequences of regional cooperation—especially how cooperation relates to the income gap between urban and rural residents—remain underexamined. This study addresses that gap by asking whether, and through which channels, horizontal cooperation affects the distribution of income between urban and rural areas.

On the other hand, extensive literature examines the determinants of the urban–rural income gap from multiple perspectives. Institutional reforms such as fiscal decentralization [11], social security integration [12], hukou rules [13], and property-rights changes [14] are shown to shape the urban–rural income gap. Infrastructure investments also matter: road construction is often associated with a narrower urban–rural income gap [15,16]; digital and network infrastructure effects vary with development stage and complementary policies [17]. Programmatic interventions—such as conditional cash transfers (CCTs) [18], China’s targeted poverty alleviation (TPA) [19], and seasonal migration subsidies [20]—further illustrate that policy design can narrow the urban–rural income gap when targeting is precise and complementary services are in place. While these studies extensively analyze the impact of single factors or policies on urban–rural income gaps, none have incorporated regional cooperation into their analytical frameworks.

Finally, research on the relationship between regional cooperation and the urban–rural income gap remains preliminary, and systematic conclusions are lacking. Some studies examine the effects of regional cooperation policies on interregional disparities. Crucitti et al. [21] evaluated European Union Cohesion Policy investments (2014–2020) and found that they significantly narrowed regional socioeconomic gaps. Using the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area as a case, Zhang et al. [22] found that regional cooperation reduced regional inequality. Other work investigates regional policies and urban–rural development. Zhang et al. [23] found that the Yangtze River Delta integration policy effectively promoted integrated urban–rural development. Li et al. [24] observed that integrated regional expansion significantly narrowed the urban–rural income gap. Existing research has yet to directly analyze the impact of regional cooperation on urban–rural income disparities, with most studies focusing on related areas of analysis.

The extant literature offers a useful foundation, but three gaps remain. First, there is no integrated theoretical framework that explicitly links the design of regional cooperation mechanisms to the urban–rural income distribution. Existing studies either emphasize regional growth while abstracting from inequality or analyze income disparities without incorporating cooperation as a structural determinant. Second, credible causal evidence on the effects of regional cooperation on the urban–rural income gaps is limited, especially large-sample analyses from developing-country contexts. Third, mechanism evidence is thin: the specific transmission channels through which cooperation shapes distributional outcomes are rarely unpacked, leaving the “black box” largely closed.

Motivated by these gaps, this study investigates the impact of regional cooperation on the urban–rural income gap, using China’s EWC as a representative policy setting. It aims to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and to offer theoretical and empirical guidance for developing economies seeking distributionally inclusive regional policies. Three questions are addressed: (i) does regional cooperation materially affect the urban–rural income gap; (ii) through which pathways does any effect operate; and (iii) does the impact exhibit heterogeneity across contexts? To answer these, a staggered difference-in-differences (DIDs) design is utilized on a balanced panel of 642 western counties from 2013 to 2020. The estimates show that EWC significantly narrows the urban–rural income gap by increasing rural incomes rather than altering urban incomes. Mechanism evidence indicates two principal channels: improved employment outcomes for farmers and higher agricultural production efficiency. The policy effect is stronger where initial inter-county economic disparities are larger, geographic distance between paired counties is shorter, agriculture accounts for a higher local share, and in the Southwest region. These findings provide actionable evidence for designing regional cooperation that promotes more equitable income distributions in developing countries.

This paper makes three contributions. First, it develops a testable framework linking horizontal cooperation to equity-enhancing growth, defined as raising rural incomes without depressing urban incomes. Second, it provides credible large-sample evidence from a developing-country context that regional cooperation narrows the urban–rural income gap. Third, it offers mechanism evidence that employment expansion and improvements in agricultural productivity are operative channels, informing the design of cooperation mechanisms aligned with SDG 10.

2. Policy Background and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Policy Background

As the world’s largest developing economy, China has long faced unbalanced development across regions. Since the reform and opening-up, eastern coastal areas have rapidly developed through their location and policy advantages, while the less-developed western regions have developed slowly because of geographical constraints and insufficient endowments. Consequently, interregional income disparities in China have intensified [25]. In the 1990s, a sharp contrast emerged between the prosperity of the eastern coastal regions and the poverty in western regions [26]. To alleviate poverty in western China and mitigate the income inequality among regions, the developed regions in eastern China have initiated intergovernmental assistance programs aimed at supporting the underdeveloped regions in the west since 1996. Under the administrative impetus of the central government, developed eastern regions and less-developed western regions in China have transcended regional administrative boundaries to implement cooperation measures that encompass fiscal assistance, industrial cooperation, and labor cooperation [27].

In 2016, China’s antipoverty campaign underwent an institutional transformation: the State Council issued the 13th Five-Year Poverty Alleviation Plan [28], set binding 2020 targets to lift all rural residents below the national poverty line out of absolute poverty, strengthened monitoring and evaluation, clarified responsibilities across all levels of government, and established a strict accountability and oversight system [29]. National inputs of human, material, and financial resources increased substantially, and EWC was upgraded to support the goals of winning the battle against poverty [30]. The issuance of Guiding Opinions on Further Strengthening the East–West Cooperation in Poverty Alleviation in 2016 marked a comprehensive enhancement of EWC along four dimensions [31]. First, the scope expanded beyond economic development to encompass infrastructure construction, basic public services, science and technology, cultural exchange, and social governance. Second, the policy toolkit diversified to include industrial cooperation, labor-service cooperation, talent programs, fiscal transfers, social participation, and consumption-based assistance, enabling more precise support to underdeveloped regions. Third, the intensity of assistance increased markedly: during 2016–2020, eastern provinces and municipalities transferred CNY 76.536 billion to their paired western counterparts (annual mean CNY 15.307 billion), nearly 30 times the 1996–2015 annual average; over the same period, eastern enterprises invested CNY 865.45 billion in partner regions (annual mean CNY 173.09 billion), a 1.5-fold increase relative to 1996–2015. Fourth, pairing arrangements were refined: under the 2016 “Join Hands to Build a Moderately Prosperous Society” initiative, developed eastern counties established direct partnerships with underdeveloped western counties, enabling more targeted interventions. The county-to-county partnerships under the EWC were initiated in two phases, in 2016 and 2017. From the establishment of these pairings, assisted counties in the western region have been continuously supported by their more developed eastern counterparts.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

2.2.1. Regional Cooperation and Income of Farmers

Since the reform era, China’s urban–centered development strategy and the hukou institution have jointly amplified urban–rural income disparities via segmented factor markets and unequal access to public services [32,33]. Against this backdrop, diversifying rural income sources and accelerating farmers’ income growth are regarded as pivotal levers for narrowing the urban–rural divide. However, agricultural production has remained inefficient [34]. Moreover, the human capital of rural residents has been limited. Consequently, rural incomes have significantly lagged behind urban incomes [35].

The EWC has been designed as a rural-oriented policy initiative. Targeting has been focused on rural populations in western China to alleviate poverty and raise incomes among impoverished residents [36]. In rural communities, two primary income sources have been identified [37]. Wage earnings arise from non-agricultural sectors. Productive income is generated by agricultural production. Through the implementation of EWC, dual objectives have been pursued. First, employment opportunities and self-development capabilities have been enhanced via targeted job transfers, reduced labor-mobility costs, human capital development, and improved public services. Wage income of farmers in assisted regions has thus been increased [38,39]. Second, resource allocations to assisted counties have been expanded. The distribution of agricultural production factors has been optimized. Efficiency has been improved. Ultimately, greater income from farming activities has been enabled [40].

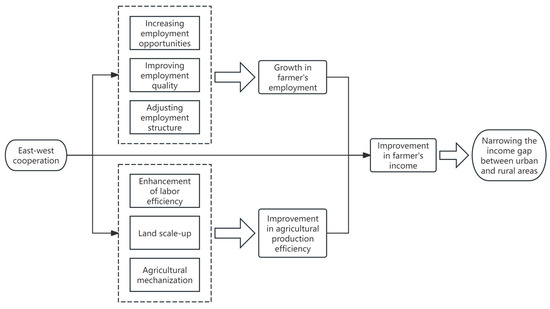

Taken together, employment and income channels for farmers in assisted regions have been broadened. Concurrently, factor flows between farm and nonfarm activities have been rebalanced toward greater efficiency. Because this reallocation has prioritized rural development and farmers’ income growth, rural earnings have increased. Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework linking EWC to the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties. Based on these considerations, the research hypotheses are proposed.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

Hypothesis 1.

The EWC can narrow the urban–rural income gap.

Hypothesis 2.

The EWC can narrow the urban–rural income gap by increasing the income of rural residents.

2.2.2. Regional Cooperation and Employment of Farmers

EWC can narrow the gap by transforming rural labor-market outcomes along three margins. First, industrial relocation and labor cooperation have broken spatial constraints in rural labor markets under the urban–rural dual structure. A dual track of “local employment + cross-regional placement” expands job availability for western rural workers. Locally, labor-intensive manufacturing and agri-processing transferred from the East create suitable positions aligned with prevailing skills [41,42]; cross-regionally, standardized “demand–supply–matching” mechanisms reduce information frictions and facilitate entry into higher-productivity sectors [43].

Second, human capital has been strengthened through educational support and vocational training. Using microdata from the China Labor-force Dynamics Survey, recent evidence for rural China shows that graduates of upper-secondary vocational schools experience higher income and greater employment stability than their peers from the academic track [44]. Complementary randomized evaluations of sector-focused, employer-aligned training document persistent earnings gains when occupation-specific training is paired with job placement and post-placement support, largely by moving participants into higher-wage occupations rather than merely increasing employment rates [45]. Consistent Chinese evidence indicates positive and time-varying wage returns to vocational education from 2010 to 2017, which aligns with a labor market that increasingly rewards employer-relevant skills [46]. In light of this literature, the order-based training partnerships under EWC, which align curricula with eastern firms and connect trainees to specific vacancies, are expected to raise the quality of rural employment and to facilitate movement from low to higher value-added roles.

Third, industrial cooperation between eastern and western regions has promoted industrial integration and supply-chain extension in underdeveloped western areas, thereby driving industrial-structure upgrading. On one hand, western rural areas have leveraged value-chain linkages with eastern regions to develop an integrated employment system spanning agricultural production, processing, and services. Farmers’ income sources have been diversified from single-crop cultivation to a multi-tiered model combining land-lease rent, labor wages, and profit-sharing [47,48]. On the other hand, returnee entrepreneurship has generated an employment multiplier. This effect is supported by policy packages that integrate entrepreneurship subsidies, technical assistance, and expanded market access. Migrant workers with experience in eastern cities have been encouraged to start businesses at home, thereby drawing more farmers toward non-agricultural employment or part-time work [49].

Established research shows that expanding rural employment and facilitating labor reallocation raise rural household incomes and can narrow the urban–rural income gap. Comprehensive reviews of the rural nonfarm economy document its role in boosting growth, employment, and spatial equity in developing countries [50]. For China, migration and off-farm work have been shown to increase rural household incomes in ways consistent with a narrowing of the rural–urban divide [51]. Importantly, when migrants are incorporated into the income distribution, the measured urban–rural income gap shrinks—by about 10% in benchmark comparisons for the early 2000s—underscoring the equalizing contribution of employment-driven labor mobility [52]. Cross-country evidence further indicates that reallocating labor from low- to higher-productivity sectors is a central mechanism through which developing economies raise average earnings and reduce dispersion, a pattern especially pronounced in Asia [53]. Taken together, the existing literature has sufficiently demonstrated that expanding rural employment will translate into higher rural incomes, thereby narrowing the urban–rural income gap.

Therefore,

Hypothesis 3.

The EWC can increase rural employment and earnings, thereby contributing to a narrower urban–rural income gap.

2.2.3. Regional Cooperation and Agricultural Production Efficiency

Institutional foundations for agricultural efficiency enhancement have been established through rural land-system innovation [54,55]. With support from eastern regions, standardized land-transfer service platforms have been created in underdeveloped western areas. Land transaction costs have been reduced. Land resources have been concentrated among large-scale growers, family farms, and agricultural enterprises [56]. Scale economies lower unit costs and improve machinery utilization [57]. Moreover, a shift from decentralized smallholder farming to specialized, standardized models has been driven, thereby significantly boosting land productivity [56].

The EWC effectively optimizes labor allocation. Consistent with dual-economy logic, targeted agricultural technology extension improves the skills of those who remain in farming [58,59], while off-farm migration of surplus labor raises marginal productivity in agriculture [60]. The combination of skill upgrading for stayers and reallocation of surplus labor transforms production from “excess low-skill labor” to skill-aligned workforces, thereby increasing labor productivity per unit [61].

Technological diffusion is accelerated through the alignment of the eastern region’s technological advantages with the western region’s agricultural development needs. Technological progress is the primary driver of total factor productivity (TFP) improvement [62]. Modern agricultural technologies have been introduced in less-developed western regions. Farming has shifted from “experience-based” to “precision-oriented” practices. Resource consumption and production costs have been reduced. On the other hand, jointly building agricultural technology demonstration zones as technology transfer carriers accelerates the implementation of scientific and technological achievements through the “core area–radiation area” model, generating regional technology spillover effects [63]. The integration of technological factors with other production factors has directly enhanced individual factor productivity. Moreover, overall TFP growth has been driven by optimized factor combinations.

According to the Lewis dual-economy model, improvements in agricultural productivity increase the marginal product of rural labor, raise rural wages, and facilitate labor reallocation to higher-productivity sectors, thereby reducing the income gap between urban and rural areas [64]. Similarly, the agriculture–industry linkage theory proposed by Johnston and Mellor emphasizes that rising agricultural efficiency generates surplus, lowers food prices, and stimulates nonfarm rural activities through forward and backward linkages, leading to broader income sources and convergence in rural and urban incomes [65]. These classical insights are supported by recent empirical findings showing that higher agricultural total factor productivity in developing countries—and in China in particular—correlates with higher rural earnings and a measurable decline in the urban–rural income gap [66,67]. Based on these considerations, the research hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 4.

The EWC can improve agricultural production efficiency, thereby increasing rural incomes and narrowing the urban–rural income gap.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The empirical analysis focuses on counties located within China’s western provinces. Counties in the western region that received EWC assistance are treated as the treatment group. Counties without such support are treated as the control group. Owing to substantial missing data in key variables for counties within the Xizang Autonomous Region and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, these samples are excluded from the analysis. Municipal districts are also excluded, as their administrative functions and management systems differ from those of ordinary counties. The final balanced panel comprises 642 counties observed from 2013 to 2020. Of these, 400 are assisted counties and 242 are non-assisted counties.

We focus on a homogeneous institutional window from 2013 to 2020. China launched targeted poverty alleviation in 2013. Some EWC-assisted counties were then designated as national-level impoverished counties and received coordinated policy support. Restricting the analysis to the period after 2013 reduces confounding from concurrent national programs and helps identify the net effect of EWC. The window ends in 2020, which marks the completion of the national poverty-elimination campaign. After 2020, the EWC framework was redesigned with updated objectives and revised pairing rules. Adding post-2020 data would combine different institutional regimes and weaken causal identification. Limiting the sample to 2013–2020 preserves a single, comparable treatment environment and consistent county-level measurement.

County-level economic data are drawn primarily from successive issues of the China Statistical Yearbook (county-level), provincial and prefecture-level statistical yearbooks, and individual county statistical yearbooks. The geographical distance between each pair of partnered counties is computed from administrative division data for 2020. The number of patents granted is obtained from the State Intellectual Property Office patent database. All nominal variables are converted to 2013 constant prices using the province-level Consumer Price Index (CPI), following Li et al. [68]. To mitigate the influence of extreme observations, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The urban–rural income gap (Incomegap) at the county level serves as the dependent variable. It is measured as the ratio of urban residents’ per capita disposable income to rural residents’ per capita disposable income within a county–year. This ratio is widely used to capture the urban–rural income gap in the Chinese context [52,69]. Conceptual definitions of “per capita disposable income” follow the National Bureau of Statistics: disposable income includes wages, net business income, net property income, and net transfer income. Hence, the ratio offers a transparent and policy-relevant indicator of the urban–rural income differential.

3.2.2. Core Independent Variable

The core independent variable is the EWC treatment indicator did. It is defined as the product of two binary terms: (i) a post-adoption indicator that equals 1 from the year county i formally enters the EWC program onward, and (ii) an assistance-status indicator that equals 1 for counties designated as assisted units. Two cohorts of assisted counties were admitted in 2016 and 2017. Accordingly, did = 1 for assisted counties in the year their partnership is established and all subsequent years, and did = 0 otherwise. With this approach, this study is more rigorous in the empirical treatment than are previous studies. Some studies [30,70] consider only the sample of the assisted counties in 2016 and ignore the sample of the assisted counties in 2017, and even the sample of the assisted counties in 2017 were wrongly included in the control group of some studies for policy effect identification. The omission and misunderstanding in sample selection affect the accuracy of the empirical results. Building on prior scholarship, we introduce methodological refinements to sharpen the identification of the EWC policy’s impact.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Industrial Structure (Secondgdp). Structural transformation and the dual-economy theory have linked the sectoral composition of output and employment to urban–rural income inequality [64,71]. A higher non-agricultural or secondary-industry share may widen the urban–rural income ratio when new jobs are urban-biased, while diffusion of nonfarm activities toward rural areas can compress the gap [25]. In this study, industrial structure is captured by the share of secondary-industry value added in county GDP, a conventional proxy in the structural-transformation literature [72,73].

Level of Financial Development (Finance). Theory and evidence suggest a non-linear, inverted U pattern between financial development and overall inequality: in early deepening, gains are often urban-biased and the gap may widen, while broader access later helps narrow disparities [74]. Consistent with spatial credit allocation mechanisms, rural branch expansion can mitigate rural disadvantages [75]. In this study, the level of financial development is reflected in the ratio of the year-end financial institutions’ loans to county GDP, which has been linked to investment, firm expansion, and household income formation [76,77].

Fiscal Expenditure Scale (Fiscal). Studies have shown that the scale and composition of public finance shape distribution through local public goods, infrastructure, and redistributive programs [78]. Rural-biased expenditure tends to raise farm incomes and mitigate urban–rural inequality, whereas urban-tilted outlays may not [79]. The scale of fiscal expenditure is gauged by the ratio of local general public budget expenditure to county GDP, following the public-spending and growth tradition [80,81].

Innovation Intensity (Innovation). Endogenous growth theory has shown that local innovation and knowledge diffusion are key determinants of productivity and earnings [82]. While inventive activity often concentrates in cities, spillovers and adoption can raise rural productivity and narrow gaps when technologies diffuse effectively [83]. Referring to common measurement in the innovation literature, innovation intensity enters through the number of patent grants per 10,000 residents, as patent counts provide an internationally comparable indicator of inventive output [84,85].

Human Capital (Education). Human capital earnings theory shows that schooling raises individual productivity and wages; rural schooling deficits therefore widen the urban–rural income gap, while convergence in years of schooling narrows it [86]. In this study, human capital is represented by average years of schooling, a stock measure widely used in development research [87,88,89].

Taken together, these variables account for contemporaneous differences in industrial structure, level of financial development, fiscal capacity, innovation intensity, and educational attainment, thereby mitigating omitted-variable bias.

3.2.4. Mechanism Variables

The theoretical analysis in Section 2.2 indicates that the impact of EWC on the urban–rural income gap is primarily achieved by raising rural incomes rather than altering urban incomes. Our theoretical analysis further suggests that EWC policies contribute to narrowing the income gap by promoting employment among farmers and enhancing agricultural productivity. To empirically validate this theoretical analysis, we introduce four mechanism variables: rural per capita income, urban per capita income, farmers’ employment level, and agricultural production efficiency.

With respect to income measures, rural per capita disposable income (Ruralincome) and urban per capita disposable income (Urbanincome) are adopted, and their logarithms are used in the regressions. Regarding employment, the number of rural employees (Employees) serves as a proxy, and its logarithm is used in the regressions. For agricultural production efficiency, the change in total factor productivity of agriculture (TFPCH) serves as the proxy variable [90,91]. TFPCH is calculated using the DEA–Malmquist index approach, with output measured by primary-industry value added and inputs comprising land (sown crop area), labor (number of primary-industry employees), and capital (total power of agricultural machinery) [90]. Table 1 reports the descriptive statistical characteristics of the variables.

Table 1.

Definitions and descriptions of the variables.

3.3. Model

The EWC program was assigned to county cohorts in 2016 and 2017 according to central matching rules and then remained in place. This creates a plausibly exogenous, staggered policy environment at the county level over 2013–2020. A difference-in-differences design with county and year fixed effects is therefore well suited to estimate the average treatment effect while absorbing time-invariant county characteristics and common shocks. Therefore, based on balanced panel data from 2013 to 2020, we employ the staggered DIDs model to identify the impact of EWC on the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties.

The baseline regression model is specified in Equation (1):

where represents the urban–rural income gap of county i in year t. is the core independent variable defined above. Cohort-specific intervention years are 2016 and 2017; for each treated county, equals 1 in and after the year its pairing begins, and 0 otherwise. To ensure unbiased estimation, we include year fixed effects and county fixed effects . is the random error term.

Based on the theoretical analysis in Section 2.2, we hypothesize that EWC will narrow the urban–rural income gap by increasing rural employment and enhancing agricultural production efficiency. The narrowing effect of rural employment expansion [50,51,52,53] and agricultural production efficiency growth [64,65,66,67] on urban–rural income gap has been thoroughly explained and demonstrated by numerous theories and literature, and we have already analyzed this in the theoretical analysis section. Therefore, we will adopt the methodology of Jiang [92] and Chen et al. [93], focusing on verifying the impact of the EWC on rural employment and agricultural production efficiency. This aims to validate the theoretical analysis that EWC influences the urban–rural income gap through these two channels. Based on this, we establish the following regression model:

where represents the mechanism variables. First, the direct impacts of EWC on the income levels of rural and urban residents are analyzed. Second, two transmission channels through which the policy may raise rural income—expanding farmers’ employment and improving agricultural production efficiency—are examined. Accordingly, the mechanism variables comprise rural income, urban income, the level of rural employment, and agricultural production efficiency. The remaining control variables are kept identical to those in Equation (1).

Prior empirical studies [30,70] on the policy effects of EWC rely on the DIDs model, and model the intervention as having a single common onset by treating only 2016 assisted counties as exposed. By leaving the 2017 assisted counties in the control group for the post period, this approach can conflate later-treated units with never-treated units, creating a cohort-selection omission and a design–estimator mismatch that may distort the average treatment effect. In this study, we accurately identify both the 2016 and 2017 assisted counties and employ staggered DIDs with county and year fixed effects, aligning the estimator with the EWC program’s rollout and yielding a more precise assessment of EWC’s impact on the urban–rural income gap.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

Building upon the theoretical framework outlined in Section 2.2, the following empirical analysis is conducted to test the proposed hypotheses, with particular attention to Hypothesis 1 concerning the impact of the EWC on the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties.

Table 2 presents the baseline regression results for the effect of EWC on the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties. In Column (1), only county and year fixed effects are controlled for, whereas in Column (2), the control variables are additionally incorporated into the regression. In both Columns (1) and (2), the coefficient of did is statistically significant, carries a negative sign, and exhibits a relatively stable magnitude. The estimates from Column (2) are adopted as the baseline regression results for subsequent analysis. Specifically, the results in Column (2) show that the coefficient of did is −0.1118 and significant at the 1% level, indicating that EWC reduces the urban–rural income ratio by 0.1118 points. Relative to the pre-treatment mean of 3.23 for recipient counties, this corresponds to a 3.46% decline, indicating an economically meaningful effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is empirically supported.

Table 2.

Results of baseline regression.

4.2. Robustness Checks

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

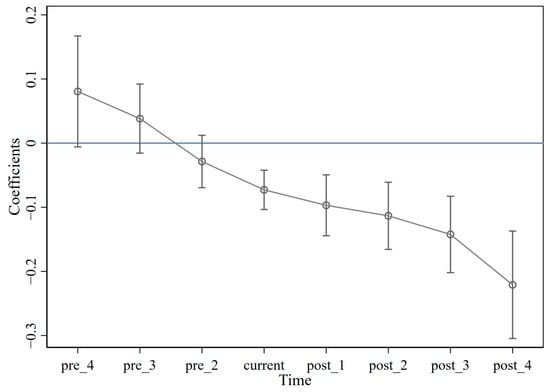

For causal identification using a staggered DIDs model, it is required that the treatment and control groups display the same trend in relevant variables before policy implementation. Based on this requirement, the event-study approach was employed to assess the identifying assumption of parallel trends. Event time is indexed to the year in which each assisted county established its East–West pairing. Nine event-time indicators—pre_4, pre_3, pre_2, pre_1, current, post_1, post_2, post_3, and post_4—are constructed to span the implementation year and the four leads and four lags. These dummy variables were sequentially interacted with did and re-estimated in the baseline regression model.

The year immediately preceding policy implementation (pre_1) was designated as the reference group. As shown in Figure 2, before the formation of the pairing relationship, the coefficients of the interaction terms were statistically insignificant, indicating no significant difference in the pre-policy trend of the urban–rural income gap between treatment and control counties. In contrast, after the implementation of the policy, the coefficients on the interaction terms became statistically significant, exhibited negative signs, and demonstrated a clear downward trend as the duration of cooperation increased. This pattern implies that, as the duration of EWC continues to extend, its impact on narrowing the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties is increasingly evident. These findings further reinforce the credibility of the baseline regression results presented in this study.

Figure 2.

Parallel trend test.

4.2.2. PSM-DIDs

Because the selection of assisted counties in the western region comprehensively considered indicators such as the level of economic development, the income level of farmers, and the proportion of the population living in poverty—and given that many of these counties were formerly designated as deeply impoverished areas to accelerate the eradication of absolute poverty—there is a potential concern regarding sample self-selection. To further mitigate the influence of this issue on the regression results, the propensity score matching difference-in-differences method (PSM-DIDs) was employed to examine the urban–rural income distribution effects of the EWC.

The procedure was as follows: first, a logit model was estimated with the inclusion of covariates, namely the control variables described above, to calculate the propensity scores. Based on these scores, the control group was matched to the treatment group, ensuring that the two groups exhibited no statistically significant differences before the implementation of the pairing assistance policy, thereby reducing bias caused by sample selection. Both nearest-neighbor matching and kernel matching techniques were applied. After matching, the mean values of the covariates for the treatment and control groups were found to be statistically indistinguishable at the 10% significance level, satisfying both the balance and common support assumptions, which indicates a satisfactory matching quality.

Subsequently, observations outside the common support domain were excluded, and the staggered DIDs model was re-estimated. The results, reported in Table 3, indicate that the coefficient of did remains significantly negative, thereby confirming that the narrowing effect of the EWC policy on the urban–rural income gap is robust.

Table 3.

Results of PSM-DIDs.

4.2.3. Placebo Test

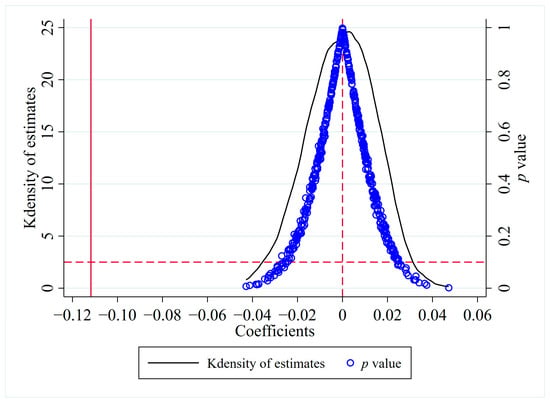

Given that unobserved factors not accounted for in the model may still influence the effectiveness of the EWC during its implementation, a placebo test is conducted to further verify the robustness of the findings. In a conventional single-period DIDs setting—where the policy implementation year is uniform—a placebo test can be performed by randomly selecting, from all sample counties, the same number of counties as in the actual treatment group and designating them as the placebo treatment group. However, because the implementation of EWC in assisted counties occurred in different years, both treatment-group dummy variables and policy-timing dummy variables needed to be generated. Specifically, a random policy implementation year is assigned to each sample county, and a corresponding placebo treatment indicator was created.

Based on this approach, 500 random policy shocks are simulated, each time selecting 400 counties at random as the placebo treatment group and randomly assigning their policy implementation year. This procedure produces 500 sets of placebo interaction terms—didrandom. The kernel density distribution of the 500 estimated coefficients and the distribution of their p-values are presented in Figure 3. The results show that the randomly generated coefficients are concentrated around zero, with most p-values exceeding 0.1, and the actual policy coefficient is −0.1118, clearly distinct from the placebo distribution.

Figure 3.

Placebo test.

These results indicate that the estimated narrowing effect of EWC on the urban–rural income gap is unlikely to be attributable to unobserved confounders, thereby strengthening the credibility and robustness of the findings.

4.2.4. Bacon Decomposition Test

Based on Goodman-Bacon [94], because the treated units receive treatment at different points in time, the staggered DIDs may involve issues arising from heterogeneous treatment effects. Therefore, a Goodman-Bacon decomposition is conducted, which breaks the overall DIDs estimator into three groups and calculates the weight and coefficient for each. The results are presented in Table 4. It can be seen that the weight of the 2 × 2 DIDs estimator comparing later-paired assisted counties (treatment group) with earlier-paired assisted counties (control group) is only 8.7%. This indicates that the bias in the regression results obtained from the two-way fixed-effects model is small, further confirming the robustness of the baseline estimates.

Table 4.

Results of Bacon decomposition test.

4.2.5. Excluding the Potential Influence of Other Assistance Policies

Qinghai Province has long been a key assisted of targeted assistance in China. Since 2010, a series of pairing assistance policies directed toward Qinghai have been implemented, potentially creating overlapping policy effects with the EWC and thereby confounding the identification of its net effect on urban–rural income distribution. To eliminate possible interference of such assistance-to-Qinghai policies and obtain more reliable estimates, the sample was re-estimated after excluding all counties from Qinghai Province.

The regression results, reported in Table 5, indicate that the estimated coefficient of did remains highly consistent with that from the baseline regression. This finding suggests that, even after removing the potential influence of other policies, the baseline results remain robust.

Table 5.

Results of excluding the potential influence of other assistance policies.

4.2.6. Specifying Control Variables with One-Period Lags

As the baseline control variables could respond to EWC, reverse causality may induce endogeneity in the estimates. To address this concern and obtain more reliable estimates, the baseline regression is re-estimated using the one-period lagged values of the control variables.

Table 6 reports a did coefficient statistically indistinguishable from the benchmark estimate, lending further support to the stability of the findings.

Table 6.

Results of specifying control variables with one-period lags.

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

Baseline estimates point to a statistically meaningful contraction of the urban–rural income differential in beneficiary counties under EWC. Conceptually, the program operates through two complementary routes. The direct route raises rural residents’ disposable income, thereby compressing the gap. The indirect route works by promoting farmers’ employment and enhancing agricultural production efficiency. To further explore these mechanisms, we conducted empirical analysis and discussion using the staggered DIDs model in Equation (2).

4.3.1. The Impact of EWC on Urban–Rural Household Income

Table 7 reports the impact of the EWC policy on the income of urban and rural residents. Columns (1) and (2) present the effects of EWC on rural residents’ incomes, while Columns (3) and (4) present its effects on urban residents’ incomes. Columns (2) and (4) incorporate the full set of control variables. The regression results in Table 7 show that the direct impact of EWC on the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties is manifested through a significant increase in rural per capita income, while no statistically significant effect is observed for urban per capita income. According to the results in Column (2), compared with non-assisted counties, rural per capita income in assisted counties is significantly higher by 2.52%. This finding reveals the rural-oriented and inclusive nature of EWC policy. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is empirically supported.

Table 7.

Results of the impact of EWC on urban–rural household income.

4.3.2. The Impact of EWC on Farmers’ Employment

Employment is the most fundamental aspect of people’s livelihoods and represents the primary source of income for farmers [95,96,97]. The estimation results, reported in Table 8, indicate that the regression coefficient of the core independent variable did is significantly positive, suggesting that EWC has markedly promoted farmers’ employment in assisted counties. Furthermore, compared with non-assisted counties, the implementation of EWC led to a 1.61% increase in the amount of employed rural residents in assisted regions. This evidence clearly demonstrates that fostering stable employment among farmers constitutes an important pathway through which EWC facilitates sustained farmers’ income growth in assisted counties. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is empirically supported.

Table 8.

Results of the impact of EWC on farmers’ employment.

4.3.3. The Impact of EWC on Agricultural Production Efficiency

Enhancing agricultural production efficiency is essential for sustaining farmers’ income growth, as productivity gains translate directly into higher earnings [98]. Table 9 reports the impact of EWC on agricultural production efficiency in assisted counties. The results show that the regression coefficient of the core independent variable did is 0.0230 and is statistically significant. This indicates that the EWC has significantly improved agricultural production efficiency in assisted counties. This finding further demonstrates that improving agricultural production efficiency constitutes an important pathway through which EWC promotes sustained income growth among farmers in assisted counties. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is empirically supported.

Table 9.

Results of the impact of EWC on agricultural production efficiency.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on the Economic Disparity Between Paired Counties

For regions with weaker initial economic conditions, external stimuli are critical to breaking low-level equilibria and achieving high-level equilibrium transitions. Consistent with the principle of diminishing marginal effects, wider pre-collaboration disparities are followed by faster post-collaboration convergence, with gaps in farmers’ incomes narrowing at a correspondingly higher rate. To further investigate whether the effect of EWC on the urban–rural income gap in assisted counties is influenced by the economic disparity between paired counties, an indicator of absolute interregional economic disparity was constructed by matching the per capita GDP of assisted and supporting counties. Logarithmic value of this indicator (lnGap_PGDP) is then interacted with the policy variable did to form the interaction term lnGap_PGDP×did. A triple-differences estimation strategy was subsequently employed.

Table 10, Column (1), reports a negative loading on the interaction term (lnGap_PGDP × did), significant at conventional (5%) levels. Accordingly, EWC compresses the urban–rural income differential among assisted counties, and this equalizing influence is stronger where the initial inter-county economic gap is wider.

Table 10.

Results of heterogeneity analysis based on the economic disparity and geographical distance between paired counties.

4.4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on the Geographical Distance Between Paired Counties

The core of the EWC lies in optimizing the allocation of production factors between paired counties through the cross-regional integration of resource endowments. However, an increase in geographical distance between paired counties may lead to higher interregional transaction costs for goods and production factors, increased costs of labor transfer and employment, and more severe information asymmetries. Consequently, the policy effect of EWC is likely to weaken as the geographical distance between paired counties increases.

To assess whether spatial proximity conditions EWC’s equalizing impact on urban–rural incomes, great-circle distances were computed between each assisted county and its supporting counterpart using their latitude–longitude centroids. The natural logarithm of this measure (lndis) was then interacted with the policy variable (did) to construct the term (lndis × did). A triple-differences approach was subsequently employed for the empirical analysis.

As shown in Table 10, Column (2), the interaction (lndis × did) enters with a positive sign and is statistically significant at 1% threshold. Hence, greater spatial separation between paired counties attenuates the equalizing impact of EWC on urban–rural incomes.

4.4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on the Development Endowment and Model of Assisted Counties

Regional asymmetries in resource endowments and stages of development imply that the distributional impact of EWC is not uniform. Within the western program area, the Northwest and the Southwest differ markedly in ecological assets and developmental bases, and these contrasts shape both the mode and direction of cooperation. The Northwest—rich in energy and mineral reserves—typically orients collaboration toward energy-based infrastructure, resource-processing industries, and the upgrading of traditional agricultural activities. By comparison, the Southwest exhibits a more diversified and flexible industrial profile and benefits from favorable agro-climatic conditions; this setting supports modern agriculture and encourages cross-sector integration. Consequently, the region has prioritized diversified industrial cooperation, vigorously advancing jointly developed industrial-park schemes, through which EWC has fostered green agriculture, manufacturing, and a range of emerging industries.

To further verify whether EWC’s effect on narrowing the urban–rural income gap differs under the distinct development endowments of the Northwest and Southwest, a grouped regression analysis was conducted. Following the geographical classification standards of the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the sample counties were divided into two groups: Northwest counties—including those from Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, and Ningxia—and Southwest counties—including those from Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi. Separate regressions were run for each group, and Table 11 reports the estimated results along with the tests for differences in coefficients between groups.

Table 11.

Results of heterogeneity analysis based on the development endowment and model of assisted counties.

Analyses run separately for the Northwest and the Southwest yield negative and statistically precise treatment effects of EWC, implying compression of the urban–rural income ratio in both macro-areas. Concordant signs and patterns reinforce the credibility of the baseline findings. Table 11 shows that the estimated coefficient equals −0.1414 for the Southwest and −0.0905 for the Northwest. The absolute value of the coefficient for the Southwest is larger, and the inter-group difference test result is statistically significant. This suggests that the narrowing effect of EWC on the urban–rural income gap is greater in the Southwest than in the Northwest. A plausible interpretation is that the Southwest’s cooperation model, centered on diversified industrial linkages and intensive upgrading in green agriculture, manufacturing, and emerging sectors, provides especially favorable conditions for income convergence.

4.4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on the Industrial Foundation of Assisted Counties

Heterogeneous effects may be generated by the implementation of the EWC across counties with different industrial foundations. Since agriculture is the key sector influencing urban–rural income disparities in assisted counties, the share of primary-industry value added (primary) in 2015 is employed as a proxy for each county’s industrial foundation. This variable was interacted with the EWC policy variable did and incorporated into the model for a triple-differences analysis to investigate whether the effect of EWC on the urban–rural income gap varies across counties with different industrial foundations. The estimates reported in Table 12 show a negative and statistically significant coefficient on the interaction term (primary × did). The evidence indicates that EWC achieves greater gap-narrowing where agriculture constitutes a larger share of local output.

Table 12.

Results of heterogeneity analysis based on the industrial foundation of assisted counties.

The underlying mechanism is that the rural-oriented and farmer-inclusive design of EWC is closely aligned with the industrial structural characteristics of counties where agriculture represents a substantial share of economic output. As a result, the intended policy objectives are achieved more effectively. In such counties, EWC assistance funds and projects are more likely to be directed toward towns and villages, with a strong focus on agricultural industrial cooperation, consumption-based cooperation, and labor cooperation. The resulting benefits tend to “settle” locally in rural areas rather than being diverted to urban sectors. Beyond generic support, the EWC targets binding constraints along the production–processing–marketing chain, alleviates price-premium frictions, and facilitates intersectoral labor mobility. These interventions jointly raise rural households’ self-employment revenues and wage earnings, thereby accelerating convergence in urban–rural incomes. In contrast, in counties where agriculture accounts for a smaller share of output, income disparities are more heavily driven by urban-sector wage premiums and returns on assets. In such contexts, EWC projects and capital are more readily absorbed by industrial parks and urban industries, resulting in lower participation rates and weaker transmission elasticity on the rural side. Consequently, the policy dividends tend to accrue disproportionately to urban sectors and enterprises, thereby diluting the gap-narrowing effect.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions and Discussions

Addressing income disparities lies at the heart of the UN’s SDGs. Against this backdrop, China has implemented the EWC program—a regional cooperation program shaped by the country’s institutional and developmental conditions. This study assesses the impact of the EWC on the urban–rural income inequality in China, employing the staggered DIDs model with a balanced panel of 642 counties for 2013–2020. The estimates indicate a substantive contraction of the urban–rural income divide among assisted counties, and this conclusion remains robust across a series of robustness checks. Mechanism analyses reveal that the convergence in income levels is primarily attributable to increases in rural income, achieved through expanded rural employment and higher agricultural production efficiency.

Furthermore, the heterogeneity assessment indicates that cooperation’s impact is contingent upon local conditions across regions. The policy exerts stronger effects when the economic gap between paired counties is wider and the geographical distance smaller, underscoring the importance of economic and spatial matching in cooperation design. In addition, the impact is more pronounced in the Southwest than in the Northwest. Moreover, the evidence indicates that, in counties with a larger agricultural share, the policy is especially effective at reducing the urban–rural income gap. These results underscore the rural orientation and farmer inclusiveness of the policy and provide empirical guidance for refining regional cooperation policies to foster sustainable income convergence.

Our estimates show that EWC narrows the urban–rural income ratio chiefly by raising rural earnings through employment expansion and agricultural productivity gains, with results robust to matching, placebo, and decomposition checks. This conclusion is consistent with evidence on intermunicipal cooperation: Bel and Warner [5], using a comparative review of shared-service arrangements, show that pooling resources and organizing joint service delivery create capabilities and cost sharing that privatization or contracting out do not achieve. In our context, this joint capacity takes the form of employer-linked training and job placement and of agricultural service platforms, which together raise rural earnings. Relative to existing EWC evaluations that emphasize aggregate performance, our findings speak to the distributional margin. Using city-level data on pairing assistance, Qiu et al. [30] analyzed the economic growth effects of EWC, documenting macrolevel gains rather than distributional changes. A county-level study on “high-quality development” by Zou and Zhou found positive macro effects associated with EWC, focusing on county development outcomes at large [70]. Building on these contributions, our paper adds the distributional dimension by showing that average gains materialize on the rural income side, which translates into a smaller urban–rural income ratio in treated counties. In addition, our heterogeneity patterns match the program logic of targeted support and capacity building summarized in national assessments. World Bank emphasizes targeted antipoverty interventions, local capabilities, and context-sensitive delivery as key ingredients of recent poverty reduction in China [27]. In line with this perspective, we find larger EWC effects where baseline urban–rural gaps are greater, partner distances are shorter, and agriculture is more prominent, indicating that design margins related to need, proximity, and sectoral structure condition the distributional payoffs of cooperation.

5.2. Policy Implications

Regional cooperation should be further strengthened by deepening its rural orientation and farmer inclusiveness. Future policy design should reinforce a “rural-first” principle by prioritizing the allocation of key resources—including fiscal transfers, industrial projects, and vocational training programs—toward rural areas.

The labor cooperation mechanism should be improved with an explicit employment-oriented focus. As the expansion and upgrading of rural employment constitute a primary driver of urban–rural income convergence, practical emphasis should be placed on standardized matching mechanisms between labor supply and demand and demand-driven vocational training.

Industrial cooperation and technical cooperation should be leveraged to enhance agricultural productivity and thereby support farmer income growth. Agricultural productivity is now central to narrowing the urban–rural income gap. Regional cooperation should scale up cooperation activities that demonstrably raise agricultural productivity, notably technology extension and demonstration platforms embedded in local value chains.

Regional cooperation models should be tailored to local conditions to improve policy targeting and effectiveness. Given the substantial heterogeneity in regional development endowments and industrial structures, differentiated support strategies are warranted. In addition, a refined pairing mechanism for regional cooperation should be established. Matching rules should ensure that “relatively most developed” areas assist their “relatively least developed” counterparts, while simultaneously adhering to a “proximity principle” to maximize policy efficacy and minimize coordination costs.

5.3. Limitations

While our analysis is rigorous and carefully executed, a few limitations remain. First, while our 2013–2020 window secures a homogeneous treatment regime and consistent county-level measurement, future work can evaluate the redesigned post-2021 EWC phase using a split-regime or multi-treatment-intensity framework once fully comparable county data become available. Second, we work with county-level aggregates, which are appropriate for a policy implemented and administered at the county level. Aggregation can, however, blur within-county variation by gender, ethnicity, employment quality, or technology adoption. Linking the county panel to household, worker, or firm microdata would sharpen incidence analysis for vulnerable groups and recover more welfare-relevant outcomes—an extension we plan to pursue as micro sources become accessible. Third, a comprehensive accounting of administrative and logistical costs lies beyond the scope of this article. A future cost-effectiveness assessment that distinguishes fiscal outlays from leveraged private inputs and scales effects to policy-relevant units would complement our findings. Fourth, external validity is bounded. The estimated effects arise in China’s institutional setting, with substantial intergovernmental coordination capacity and rural-oriented targeting. Transfer to other countries likely requires similar administrative capabilities, moderate interregional distances, and supportive training and extension systems. Fifth, this study primarily analyzes the impact of the EWC on the urban–rural income gap in recipient counties. In future research, we will further explore the impact of the EWC on specific vulnerable groups, such as women or ethnic minorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S.; methodology, Z.S.; software, Z.S.; validation, Z.S.; formal analysis, Z.S.; investigation, Z.S.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.S. and S.Z.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China Major Research Program, grant number 22ZDA091.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EWC | East–West Cooperation |

| DIDs | Difference-in-differences |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| CNY | Chinese Yuan |

| TFP | Total factor productivity |

| CPI | Consumer Price Index |

| TFPCH | Change in total factor productivity |

| PSM-DIDs | Propensity score matching difference-in-differences method |

| UN | United Nations |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Sulemana, I.; Nketiah-Amponsah, E.; Codjoe, E.A.; Andoh, J.A.N. Urbanization and Income Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, T.; Augsburg, B.; Gassmann, F.; Nimeh, Z. Leaving No One behind: Urban Poverty Traps in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2023, 172, 106388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M.E. Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Costs: Expectations and Evidence. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Gradus, R. Privatisation, Contracting-out and Inter-Municipal Cooperation: New Developments in Local Public Service Delivery. Local Gov. Stud. 2018, 44, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.F. Municipal Amalgamations and Their Effects: A Literature Review. Misc. Geographica. Reg. Stud. Dev. 2018, 22, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Caro, P.; Fratesi, U. One Policy, Different Effects: Estimating the Region-Specific Impacts of EU Cohesion Policy. J. Reg. Sci. 2022, 62, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, E. Place-Based Policies and Geographical Inequalities. Oxf. Open Econ. 2024, 3, i625–i633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Spolaore, E.; Wacziarg, R. Economic Integration and Political Disintegration. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1276–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, A. Fiscal Decentralization and Urban-Rural Inequality of Income Acquisition Opportunities: Micro Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 107859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, T. The Effect of Public Pension Insurance Integration on Income Disparities between Urban-Rural Households: Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Iwasaki, I. The Hukou System and Wage Gap between Urban and Rural Migrant Workers in China: A Meta-Analysis. Econ. Transit. Institutional Change 2024, 32, 1105–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Shi, X.; Fang, S. Property Rights and Misallocation: Evidence from Land Certification in China. World Dev. 2021, 147, 105632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Zeng, L.; Wu, K.S.; Lv, D. Transport Infrastructure and Urban-Rural Income Disparity: A Municipal-Level Analysis in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 99, 103292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Luo, N. Has Highway Construction Narrowed the Urban–Rural Income Gap? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2020, 99, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, P.; Liao, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, L. Does Network Infrastructure Construction Reduce Urban–Rural Income Inequality? Based on the “Broadband China” Policy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 205, 123486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S. The Impact of Bolsa Família on Poverty: Does Brazil’s Conditional Cash Transfer Program Have a Rural Bias? J. Politics Soc. 2012, 23, 88–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Cheng, G. Targeted Poverty Alleviation Narrowed China’s Urban-Rural Income Gap: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 157, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagakos, D.; Mobarak, A.M.; Waugh, M.E. The Welfare Effects of Encouraging Rural–Urban Migration. Econometrica 2023, 91, 803–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucitti, F.; Lazarou, N.-J.; Monfort, P.; Salotti, S. The Impact of the 2014–2020 European Structural Funds on Territorial Cohesion. Reg. Stud. 2024, 58, 1568–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zou, Y. Governing Regional Inequality through Regional Cooperation? A Case Study of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 162, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhu, D. Do Regional Integration Policies Promote Integrated Urban–Rural Development? Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Land 2024, 13, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wen, W.; Ma, W.; Jin, Y. Research on the Common Prosperity Effect of Integrated Regional Expansion: An Empirical Study Based on the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2025, 14, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R.; Zhang, X. Fifty Years of Regional Inequality in China: A Journey Through Central Planning, Reform, and Openness. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2005, 9, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C.; Sun, M. Regional Inequality in China, 1978-2006. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2008, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Four Decades of Poverty Reduction in China: Drivers, Insights for the World, and the Way Ahead; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4648-1877-6. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-12/02/content_5142197.htm (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Li, Y.; Su, B.; Liu, Y. Realizing Targeted Poverty Alleviation in China: People’s Voices, Implementation Challenges and Policy Implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2016, 8, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; Li, Y. Economic Performance of the Pairing-off Poverty Alleviation between China’ Cities. Cities 2024, 152, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-12/07/content_5144678.htm (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Zhao, X.; Liu, L. The Impact of Urbanization Level on Urban–Rural Income Gap in China Based on Spatial Econometric Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Sun, W.; Li, P.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Effects of Economic Growth Target on the Urban–Rural Income Gap in China: An Empirical Study Based on the Urban Bias Theory. Cities 2025, 156, 105518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, A.; Liu, E.M.; Wang, S.-Y.; Wang, Y. Property Rights, Land Misallocation, and Agricultural Efficiency in China. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2021, 88, 1831–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A Survey on Income Inequality in China. J. Econ. Lit. 2021, 59, 1191–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, S. Paired Assistance and Poverty Alleviation: Experience and Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la O Campos, A.P.; Admasu, Y.; Covarrubias, K.A.; Davis, B.K.; Díaz Gonzalez, A.M. Reassessing Transformation Pathways: Global Trends in Rural Household Farm and Non-Farm Livelihood Strategies with a Spotlight on Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2025, 190, 106952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Song, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. The Effects of a Multifaceted Poverty Alleviation Program on Rural Income and Household Behavior in China. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2025, 17, 319–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. Training the Disadvantaged Youth and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Bangladesh. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 149, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ma, S.; Yin, L.; Zhu, J. Land Titling, Human Capital Misallocation, and Agricultural Productivity in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2023, 165, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yang, Y. Analysis of Spatial Effects and Influencing Factors of Rural Industrial Integration in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozelle, S.; Boswell, M. Complicating China’s Rise: Rural Underemployment. Wash. Q. 2021, 44, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Li, P. Regional Poverty Alleviation Partnership and E-Commerce Trade. Mark. Sci. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, R. Does Vocational Education Matter in Rural China? A Comparison of the Effects of Upper-Secondary Vocational and Academic Education: Evidence from CLDS Survey. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.F.; Roth, J.; Hendra, R.; Schaberg, K. Why Do Sectoral Employment Programs Work? Lessons from Work Advance. J. Labor. Econ. 2022, 40, S249–S291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pastore, F. Dynamics of Returns to Vocational Education in China: 2010–2017. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, L.; Chen, J.; Deng, X. Impact of Rural Industrial Integration on Farmers’ Income: Evidence from Agricultural Counties in China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 93, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Guo, Y.; Dang, H.; Zhu, J.; Abula, K. The Second-Round Effects of the Agriculture Value Chain on Farmers’ Land Transfer-In: Evidence from the 2019 Land Economy Survey Data of Eleven Provinces in China. Land 2024, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Juan, Z. Policy Evaluation of Place-Based Strategies on Upgrading County Industrial Structures amid Economic Structural Transformation: Insights from Pilot Counties of China’s Returning Entrepreneurs. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjouw, J.O.; Lanjouw, P. The Rural Non-Farm Sector: Issues and Evidence from Developing Countries. Agric. Econ. 2001, 26, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.E.; Rozelle, S.; de Brauw, A. Migration and Incomes in Source Communities: A New Economics of Migration Perspective from China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2003, 52, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicular, T.; Ximing, Y.; Gustafsson, B.; Shi, L. The Urban–Rural Income Gap and Inequality in China. Rev. Income Wealth 2007, 53, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, M.; Rodrik, D.; Verduzco-Gallo, Í. Globalization, Structural Change, and Productivity Growth, with an Update on Africa. World Dev. 2014, 63, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Chen, L. The Impact of Land Transfer Policy on Sustainable Agricultural Development in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Huo, X. Impacts of Tenure Security and Market-Oriented Allocation of Farmland on Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from China’s Apple Growers. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z. The Impact of Farm Structure on Agricultural Growth in China. Land 2024, 13, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, F.; Razzaq, A.; Feng, Z.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Land Consolidation on Rapeseed Cost Efficiency in China: Policy Implications for Sustainable Land Use and Food Security. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1390914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.T.; Bernard, T.; Makhija, S.; Spielman, D.J. Accelerating Technical Change through ICT: Evidence from a Video-Mediated Extension Experiment in Ethiopia. World Dev. 2023, 161, 106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasehinde, T.S.; Jin, Y.; Qiao, F.; Mao, S. Marginal Returns on Chinese Agricultural Technology Transfer in Nigeria: Who Benefits More? China Econ. Rev. 2023, 78, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Huan, H. Does the Transfer of Agricultural Labor Reduce China’s Grain Output? A Substitution Perspective of Chemical Fertilizer and Agricultural Machinery. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 961648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Are There Too Many Farms in the World? Labor Market Transaction Costs, Machine Capacities, and Optimal Farm Size. J. Political Econ. 2022, 130, 636–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, S.; Dakpo, K.H. Components of Agricultural Productivity Change: Replication of US Evidence and Extension to the EU. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2023, 45, 1332–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, T. Diffusion of Agricultural Technology Innovation: Research Progress of Innovation Diffusion in Chinese Agricultural Science and Technology Parks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. Manch. Sch. Econ. Soc. Stud. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.F.; Mellor, J.W. The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 566–593. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Luo, C.; Hu, Z. Can Agricultural Industry Integration Reduce the Rural–Urban Income Gap? Evidence from County-Level Data in China. Land 2024, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Rahman, S.; Sriboonchitta, S. Addressing Rural–Urban Income Gap in China through Farmers’ Education and Agricultural Productivity Growth via Mediation and Interaction Effects. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Does Flattening Government Improve Economic Performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X. Urban Expansion and the Urban–Rural Income Gap: Empirical Evidence from China. Cities 2022, 129, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Zhou, L. The Role of East and West Cooperation in Promoting County Economy’s High-Quality Development from the Perspective of Balance: A Case Study of Pairing Assistance During the Poverty Alleviation Period. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrendorf, B.; Rogerson, R.; Valentinyi, Á. Chapter 6—Growth and Structural Transformation. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Aghion, P., Durlauf, S.N., Eds, Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 855–941. [Google Scholar]

- Comin, D.; Lashkari, D.; Mestieri, M. Structural Change with Long-Run Income and Price Effects. Econometrica 2021, 89, 311–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.; de Vries, G.J. The Structural Transformation of Transition Economies. World Dev. 2025, 191, 106977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J.; Jovanovic, B. Financial Development, Growth, and the Distribution of Income. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, 1076–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.; Pande, R. Do Rural Banks Matter? Evidence from the Indian Social Banking Experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-H.; Saadaoui, J. Bank Credit and Economic Growth: A Dynamic Threshold Panel Model for ASEAN Countries. Int. Econ. 2022, 170, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ji, Y. Finance and Local Economic Growth: New Evidence from China. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 4630–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Reforms, Investment, and Poverty in Rural China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2004, 52, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. China’s (Uneven) Progress against Poverty. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 82, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Qin, C.; Qiu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Yao, L. Digital Financial Inclusion and Comprehensive Multilevel Medical Insurance System in China. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1586780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]