1. Introduction

The recent global health crisis has exposed the vulnerabilities of development models heavily reliant on tourism. In Croatia, particularly on its islands, tourism serves not only as a primary economic activity but also as a major source of public revenues and local development funding. This dependence on tourism has made these areas particularly vulnerable to external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Across the European Union, the tourism sector plays a key role in the economy and employment. For example, tourism accounts for 4.5% of the EU’s total gross value added (GVA), though the contribution varies significantly by country. In Croatia, tourism’s share reached 11.3% of GVA in 2019, one of the highest in the EU. Similarly, the sector supports a significant portion of employment, with approximately 2.4 million tourism-related enterprises across the EU employing over 12 million people [

1,

2]. However, this heavy dependence was starkly revealed during the pandemic, when tourism turnover and value added dropped by over 40%, and employment in the sector also declined. In Croatia, tourism is economically vital, but highly vulnerable to disruptions.

The paper aims to answer two research questions. First, what factors influence residents’ support for tourism activities on islands, and second, how do factors such as risk perception, economic development, and capacity influence the segmentation of residents in terms of their support for tourism?

This research aims to explore the vulnerability and sustainability of tourism development by investigating citizens’ attitudes toward tourism development in Croatia, with a particular focus on island tourism. It examines and categorizes local citizens’ attitudes toward tourism development to identify vulnerabilities and analyze what is necessary to support sustainable tourism development and enhance community well-being. While this research primarily focuses on residents’ perceptions, it is framed within a broader topic of vulnerability in tourism, which encompasses a complex set of factors, including seasonality [

3,

4] climate change [

5] and complex supply chain [

6,

7,

8]. By analyzing citizens’ attitudes, this paper highlights the extent of community support for tourism while also uncovering weaknesses that could increase vulnerabilities. Compared to other studies that explore tourism from the residents’ perspective, the focus and novelty of this research lie in its investigation of residents’ attitudes and their segmentation regarding tourism development. This approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of the vulnerabilities and risks associated with tourism-based development. Additionally, this research incorporates the recent health crisis into the analysis, thereby addressing contemporary threats to sustainable tourism development and highlighting community vulnerabilities during times of crisis. Furthermore, this research incorporates recent health crises into the analysis, providing insight into how external shocks and disruptions intensify vulnerabilities of tourism-based development and reshape residents’ attitudes towards tourism development.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Following the Introduction,

Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature on vulnerability, resilience, and sustainability within the tourism sector.

Section 3 outlines the survey methodology and presents key characteristics of the sample.

Section 4 reports the main findings derived from the exploratory factor analysis and cluster analysis. The results are further interpreted and discussed in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 offers the main conclusions and implications for sustainable tourism development.

2. Literature Review

Tourism plays a vital role in the economic development of many regions, particularly in island and tourism-dependent destinations. However, its growth is often accompanied by complex socio-cultural and environmental challenges that threaten the long-term sustainability of host communities. In the case of Croatia, where many coastal and island communities heavily rely on tourism, the need to manage tourism to ensure sustainability, equity, and resilience has become increasingly urgent. This literature review explores the interrelated concepts of vulnerability, resilience, and sustainability in the context of tourism development, with a particular focus on residents’ attitudes. It also emphasizes the importance of context-sensitive policy responses, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The review supports the rationale for this study, which investigates and segments the attitudes of local citizens toward tourism development in Croatian island communities.

Sustainable tourism is broadly defined as tourism that meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunities for the future [

9]. It is grounded in a triple-bottom-line approach, emphasizing economic viability, environmental stewardship, and social equity. In small and environmentally fragile contexts like Croatian islands, sustainable tourism requires more than just environmental regulation; it demands participatory planning, inclusive governance, and a focus on long-term community well-being [

10].

The concept of overtourism has emerged in response to the growing recognition that unchecked tourism growth can lead to negative impacts that compromise the social, environmental, and economic sustainability of destinations. Capocchi et al. [

11] define overtourism as a condition in which tourism growth leads to a significant deterioration in the quality of life for residents and the visitor experience, often due to overcrowding, pressure on infrastructure, and a loss of local identity. Mihalič [

12] extends this understanding by situating overtourism within a broader sustainability framework, emphasizing the need to balance tourism development with the destination’s ecological, socio-political, and socio-psychological capacities. In this context, sustainability is not only about managing environmental impacts but also about ensuring that tourism does not exceed the social carrying capacity of a place. This is further illustrated by González et al. [

13], who argue that residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts serve as a key indicator of social carrying capacity, reflecting tensions between local communities and tourism pressures in heritage destinations. Together, these perspectives highlight that sustainable tourism management must consider both measurable impacts and subjective local experiences to address overtourism effectively.

Vulnerability in tourism refers to the degree to which a destination or community is exposed to and unable to cope with adverse impacts, such as environmental degradation, economic shocks, or social displacement [

14,

15]. Island destinations exhibit heightened vulnerability due to physical isolation, limited economic diversification, and environmental fragility [

16]. Climate change impacts, such as sea-level rise, extreme heat, and water scarcity, exacerbate these vulnerabilities. Meanwhile, socio-economic pressures, including seasonal dependency, aging populations, and youth outmigration, further constrain adaptive capacity [

17,

18]. In Croatia, critics have highlighted how tourism pressures contribute to overexploitation of resources, rising living costs, and gentrification, particularly in destinations like Hvar, Vis, and Dubrovnik [

19].

In contrast to vulnerability, resilience refers to a system’s ability to absorb disturbance and reorganize, while changing [

20]. In tourism, resilience emphasizes the capacity of communities to adapt to crises, such as natural disasters, pandemics, or economic downturns, while maintaining their core identity and functionality. Building resilience requires understanding community-specific vulnerabilities and integrating local knowledge into planning [

21]. In the Croatian context, efforts to promote resilience often face tension between short-term economic needs and long-term community integrity [

22].

Sustainability and resilience, though conceptually distinct, are increasingly viewed as mutually reinforcing [

23]. Sustainability emphasizes the long-term balance of ecological, economic, and social dimensions of development [

24], while resilience emphasizes adaptability and the capacity to manage change. In fragile island systems, pursuing sustainable tourism requires resilience as a prerequisite, given the increasing frequency of global shocks such as pandemics, climate change, and geopolitical instability [

25]. Conversely, sustainability principles must guide resilience strategies to avoid short-term, reactive policies that undermine long-term well-being [

26].

Understanding residents’ perceptions of tourism is critical for assessing community support for development policies. The Social Exchange Theory (SET) posits that residents weigh the perceived benefits (e.g., job creation, infrastructure) against perceived costs (e.g., crowding, cultural erosion) when forming attitudes toward tourism [

27,

28]. The Knowledge–Attitude–Practice (KAP) model further suggests that awareness and understanding of tourism’s impacts can influence behavior and support [

29]. Additionally, the Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF) explains how perceptions of risk, especially during crises, can shape public sentiment, sometimes disproportionately to actual threats [

30].

Community support is essential for successful and sustainable tourism development [

31]. When residents feel excluded or exploited by tourism development, resistance and conflict often follow, leading to social friction and policy failure. On the other hand, when residents perceive that tourism aligns with their interests and values, they are more likely to support and participate in its development [

32,

33].

Tourism attitudes are not uniform across communities. Research increasingly shows that resident perceptions vary based on demographic, socio-economic, and geographic factors. In Croatian coastal and island communities, segmentation studies have revealed significant attitude differences based on employment status, age, education, and proximity to tourist zones. For instance, a survey of Lošinj and Rab found that residents employed in the tourism sector were significantly more supportive of tourism development than retirees, unemployed residents, or students [

34]. Similarly, research in Dubrovnik identified clusters of residents with distinct perceptions: long-term residents and lower-income groups were more critical of tourism’s cultural impacts, while younger and economically engaged residents viewed tourism more favorably [

35,

36].

The segmentation of residents is critical because it highlights the limitations of treating local communities as homogeneous groups. It also enables policymakers to design more nuanced and inclusive tourism strategies that address the needs of different sub-groups within the same community. Such segmentation aligns with broader findings in the literature, which emphasize that residents’ attitudes toward tourism are shaped by multiple factors, including perceived economic gains, cultural and environmental costs, trust in governance, and opportunities for participation [

37].

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly disrupted the global tourism industry, and island communities were among the most severely affected. In Croatia, where tourism directly and indirectly accounts for approximately 25% of GDP, the economic impact was severe [

38]. Beyond economic losses, the pandemic also reshaped residents’ perceptions of tourism. A study conducted on Croatian islands during the pandemic revealed that nearly one-third of respondents had already viewed their islands as overcrowded before the crisis, and many became increasingly concerned about health risks associated with reopening to tourists [

39].

These findings illustrate how crises can function as turning points, amplifying existing concerns about sustainability and exposing underlying vulnerabilities. At the same time, they can open space for rethinking tourism models and embedding resilience into development planning [

40]. This highlights the need to incorporate crisis experiences and adaptive capacities into theoretical and practical approaches to sustainable tourism.

While broad frameworks for sustainable tourism exist, their effectiveness depends on how well they are adapted to local realities. National tourism policies often adopt a one-size-fits-all approach, which fails to account for the heterogeneous nature of Croatia’s islands. While national strategies prioritize economic growth, they may not adequately address the environmental or cultural sensitivities of small island communities [

41]. Such top–down models may accelerate unsustainable practices, particularly when local actors are excluded from decision-making. Adaptive governance, characterized by flexibility, inclusivity, and multi-level coordination, is increasingly advocated as a suitable model for managing tourism in dynamic and vulnerable contexts [

42]. In the Croatian context, participatory planning processes have shown promise in aligning tourism development with community values and ecological limits. For example, some island municipalities have introduced seasonal visitor caps, promoted ecotourism cooperatives, and established marine protected areas with local fishers and tour operators [

43].

Context-sensitive policies are essential in destinations like the Croatian islands, where vulnerabilities are spatially concentrated, and residents’ attitudes vary significantly. Policies must be informed by data on residents’ perceptions and segmentation, prioritizing participatory governance, equitable benefit-sharing, and long-term planning [

44].

The “good island” concept, developed through qualitative research on Brač, proposes a model that values rural, socio-cultural, and economic capitals as interconnected pillars of sustainable development [

42]. Such models encourage integrated, context-sensitive responses that aim to reduce risk and foster collective well-being.

Although literature offers valuable insights into sustainable tourism, vulnerability, and residents’ attitudes, several gaps remain. First, segmentation studies that explore residents’ attitudes in highly tourism-dependent island communities are scarce. While general frameworks for sustainable tourism exist, they are often applied in top–down or one-size-fits-all ways, overlooking the heterogeneity of small island contexts [

41]. Second, few studies explicitly link residents’ perceptions of tourism to broader concepts of community resilience and vulnerability, especially during crises. Third, although theoretical models such as SET, KAP, and SARF are frequently referenced, they are rarely applied comparatively or integrated into mixed-methods approaches. Lastly, the role of health crises and their influence on attitude shifts remains insufficiently addressed in empirical tourism research.

To address these gaps, this study investigates residents’ attitudes toward tourism development in Croatia’s island communities by employing factor and cluster analysis to segment respondents based on their perceptions. Unlike many previous studies, it incorporates recent crisis experiences (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic) into the analysis of local vulnerabilities. While it does not directly apply a single theoretical model such as SET or SARF, the study draws conceptually from these frameworks to interpret how perceptions of benefits, risks, and resilience influence attitudinal positions. In doing so, it contributes to both the empirical understanding of tourism vulnerability in island settings and the theoretical discourse on residents’ roles in shaping sustainable tourism pathways.

3. Methodology

The islands were selected as the focus of this research due to the significant role tourism plays in their development, with the Croatian islands being the second largest archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea, after the Greek islands. The survey was conducted among residents of the Croatian islands following the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, during the lockdown in Croatia, and just before the start of the tourist season to capture the immediate impact of the health crisis on the tourism vulnerability. The snowball sampling procedure developed by Coleman [

45] and Goodman [

46] was used for data collection. Island residents represent a hard-to-reach population, especially on smaller and more remote islands. The lack of publicly available population data about citizens living on islands, implementation challenges, and low response rates to traditional surveys are additional barriers to conducting the survey on islands and creating a representative sample. Snowball sampling has been a frequently used method to gain insight into community-specific attitudes and perceptions, and is a particularly useful methodology for collecting data on geographically or socially bounded populations [

47,

48]. The survey encompassed 45 Croatian islands which have permanent inhabitants: Brač, Cres, Čiovo, Drvenik Mali, Drvenik Veli, Dugi otok, Hvar, Ilovik, Ist, Iž, Kaprije, Koločep, Korčula, Kornati, Krapanj, Krk, Lastovo, Lopud, Lošinj, Mljet, Molat, Murter, Olib, Ošljak, Pag, Pašman, Pelješac, Premuda, Prvić, Rab, Rava, Rivanj, Sestrunj, Silba, Susak, Šipan, Šolta, Ugljan, Unije, Vir, Vis, Vrgada, Zlarin, Zverinac, and Žirje. The questionnaires were distributed electronically following a preliminary search for publicly available contact information online. This search included email addresses of municipal and local government offices on the islands, tourist boards, local media, educational institutions, health centers, civil society organizations, and private accommodation providers. The questionnaire was sent with a request to forward it to individuals potentially interested in participating in the research. Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary and anonymous.

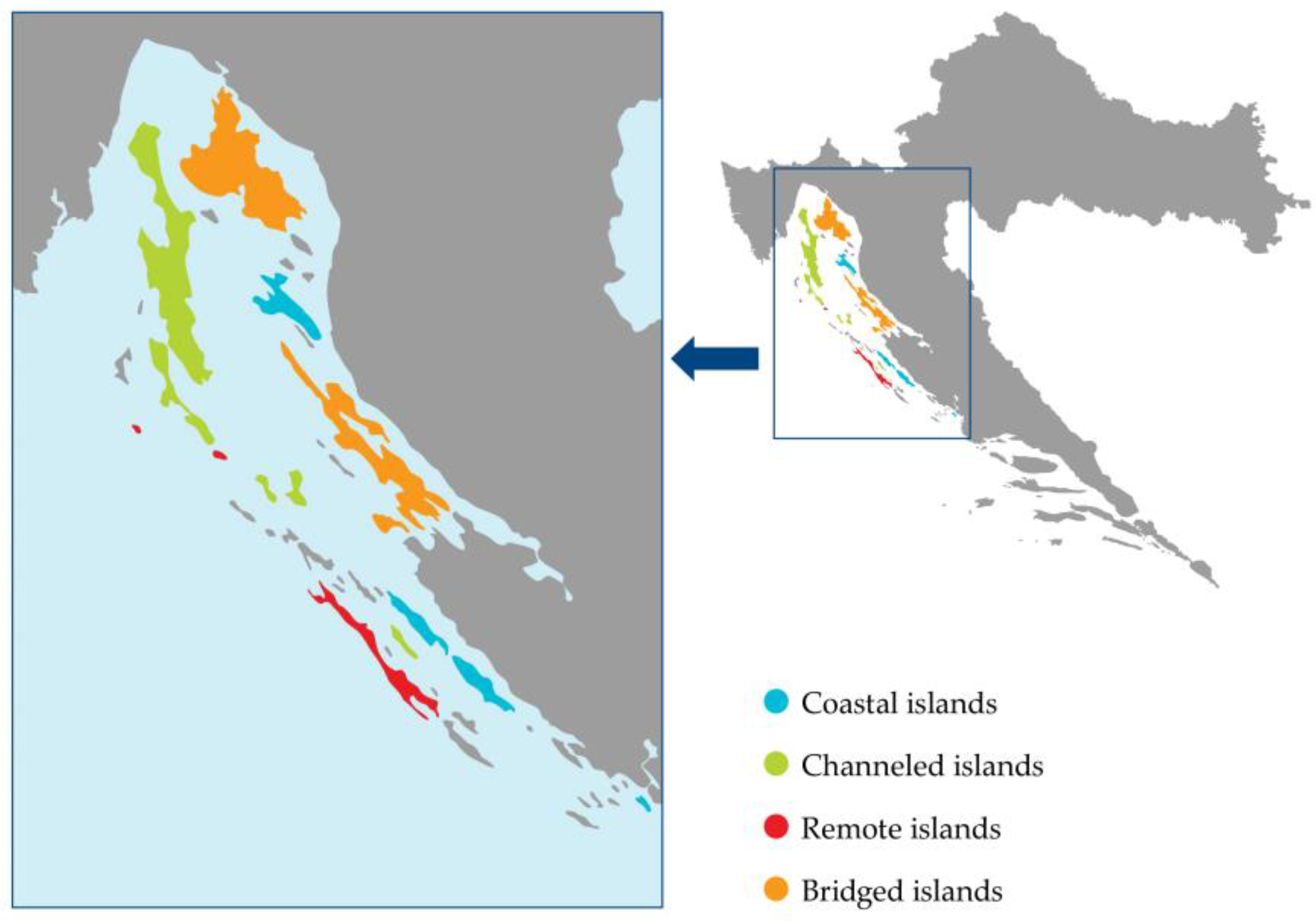

Although detailed residence information for all respondents is missing, data show that the answers were collected from respondents from a broad range of islands, specifically: Cres, Dugi otok, Ilovik, Iž, Krk, Mali Lošinj, Olib, Pag, Pašman, Rab, Silba, Susak, Ugljan, Vir, and Zlarin. These islands represent distinct geographic typologies and cover coastal islands (Rab, Pašman, Ugljan, and Zlarin), channeled islands (Cres, Iž, Olib, Silba, and Lošinj), remote islands (Dugi Otok, Susak, and Ilovik) and bridged islands (Pag, Krk, and Vir) as shown in

Figure 1. These islands differ significantly in terms of geographic size and local characteristics, suggesting that the sample captures a diverse range of island-specific contexts. While caution is warranted in generalizing the findings to the entire island population, the diversity of the sampled islands enhances the relevance and potential transferability of the results.

The sample size consists of 205 citizens, and their characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The sample consists of 41.7 percent males and 58.3 percent females. Among respondents, 35.8 percent have completed secondary school, while a majority of 64.2 percent have attained university or higher education. The age distribution shows that 17.8 percent of participants are between 18 and 34, 68.2 percent are between 35 and 59, and 14.0 percent are 60 or older. Most respondents (87.0 percent) are permanent island inhabitants, whereas 13.0 percent live there for more than three months per year.

The survey consisted of 17 questions (

Appendix A) aimed at assessing citizens’ attitudes toward tourism in their area, measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), and additional variables, age, gender, and place of residence. These questions reflect the public opinion on tourism, perceptions of the essential infrastructure required for a tourist destination, and specific inquiries concerning the impact of the pandemic on their views regarding tourism and tourist arrivals in their locality. After data collection, factor and cluster analysis were performed. Seventeen survey questions served as initial inputs for the factor analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis, a widely used method in the social sciences [

49], was employed to identify the main groups of island residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Before factor extraction, the suitability of the data was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. As indicated by “alpha-if-deleted” criteria, variables that demonstrated low sampling adequacy were identified and removed to improve the overall KMO value (

Table 2).

Principal Component Analysis served as the factor extraction method to reduce dimensionality and extract initial factors. A varimax rotation [

50] was applied to enhance interpretability. During the analysis, variables with significant cross-loadings and/or low factor loadings were excluded to improve factor clarity and interpretability. Using this methodology, 10 questions remained, covering all issues necessary to achieve the research’s purpose. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23, and factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 were retained according to the Kaiser criterion [

51]. The total variance explained with eigenvalues larger than one suggested that further analysis should proceed with three factors, which explain 60.2 percent of the variance (

Table 3).

In the next step of the analysis, we used the obtained factor scores to conduct a K-means cluster analysis, grouping citizens according to their attitudes. The validity of the cluster results was confirmed through an ANOVA, which revealed significant differences among all three clusters.

4. Results

As a result of factor analysis, local citizens’ attitudes toward tourism development, with a particular emphasis on the impact of health risk and sustainable development, can be grouped into three main factors (

Table 4).

The first factor highlights the need for a strategy to protect and control tourism in situations of increased risk. This factor combines the following variables: the island should be specially protected from tourist arrivals, the arrival of people on the island should be strictly monitored, island tourism should be distinguished from mainland tourism, and accommodation capacity for tourism on the island should be limited during periods of coronavirus risk. This factor highlights the vulnerability of tourism development to external shocks. On one hand, situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic reduced demand for tourism services [

52,

53,

54]. Conversely, these perspectives suggest that even when tourism demand remains stable, heightened vulnerability persists among populations economically reliant on the tourism sector. Crisis events compel communities to critically reassess their dependence on tourism-generated income, thereby underscoring the imperative for enhanced governmental intervention and the formulation of more robust tourism policies to bolster resilience and sustainability. This need is particularly acute in regions where tourism constitutes a principal economic activity. Furthermore, sustainable tourism development necessitates a paradigm shift that exceeds mere quantitative growth in visitor numbers, emphasizing the importance of balancing environmental stewardship with social well-being instead. Although the present study focuses primarily on the impacts of health crises on public perceptions of tourism, the findings are equally pertinent to other external shocks, including climate change, which similarly threaten the stability and sustainability of tourism-dependent economies [

23,

55].

The second factor relates to a generally positive attitude toward tourism development, reflecting perceptions of tourism as a catalyst for economic growth and local development. This dimension encompasses several key variables: the belief that tourism significantly contributes to the socio-economic advancement of the island; the view that the arrival of both domestic and international tourists should continue even amid health-related risks; and the perception that the island possesses adequate basic infrastructure to support ongoing tourism activities. Such attitudes are indicative of a development-oriented perspective, in which the benefits of tourism, such as employment generation, increased income, and improved public services, are perceived to outweigh the potential risks, including those posed by crises like pandemics [

52]. This perspective aligns with the pro-tourism attitude, often observed in regions with high tourism dependency, where residents may prioritize economic stability over health and environmental concerns [

56]. Furthermore, the belief that infrastructural conditions are sufficient reflects a foundational readiness for further tourism development, which is often linked to local perceptions of destination competitiveness [

57]. However, while such optimism may support policy initiatives aimed at sustaining or expanding tourism flows, it also raises questions about the long-term sustainability of prioritizing growth over resilience. Especially in post-crisis contexts, this growth-focused mindset must be carefully balanced against broader sustainability goals, including public health, environmental protection, and community well-being [

54].

The third factor reflects growing concerns regarding the sustainability of the island’s tourism development, particularly its spatial and ecological carrying capacity. This factor embodies the perception that the scale of tourism has become disproportionate to the island’s physical size, environmental sensitivity, and socio-cultural context. Such concerns highlight the view that tourism has reached or exceeded acceptable limits, creating pressure on local resources, ecosystems, infrastructure, and the quality of life for residents. In this context, respondents express the belief that imposing limitations on accommodation capacity is essential, signaling the need for a strategic reorientation of tourism development policies toward more balanced and sustainable models.

This viewpoint aligns with the broader discourse on overtourism, which emphasizes the negative consequences of unmanaged tourism growth in small or ecologically fragile destinations [

58]. Islands are especially vulnerable due to their limited land area, high reliance on imported resources, and fragile ecosystems [

59]. Limiting accommodation capacity is often seen as a key instrument of carrying capacity-based planning, aimed at reducing pressure on the natural environment and the socio-cultural fabric of local communities [

60]. Moreover, this factor implies dissatisfaction with existing development paradigms that prioritize economic growth over sustainability and equity. It advocates for adopting alternative tourism models, such as slow tourism, eco-tourism, or community-based tourism, emphasizing environmental responsibility, social inclusion, and long-term viability [

41]. A shift toward such models would require coordinated governance, inclusive planning processes, and adaptive policy mechanisms integrating sustainability into every phase of tourism development.

The results highlight a certain fragility in the current model of tourism development, particularly evident in Factors 1 and 3, which emphasize the urgent need to reconsider and enhance existing tourism strategies. These findings suggest that development efforts should not focus solely on increasing tourist arrivals but rather prioritize adopting alternative models that promote the sustainable development of island destinations. This includes achieving a delicate balance between the economic benefits of tourism, environmental preservation, and the overall quality of life for the local population. Existing tourism development strategies appear to be insufficiently implemented, particularly in less developed regions of Europe, thereby reinforcing the need for more coherent and balanced policy frameworks and targeted actions to effectively support the transition toward sustainable tourism destinations [

61].

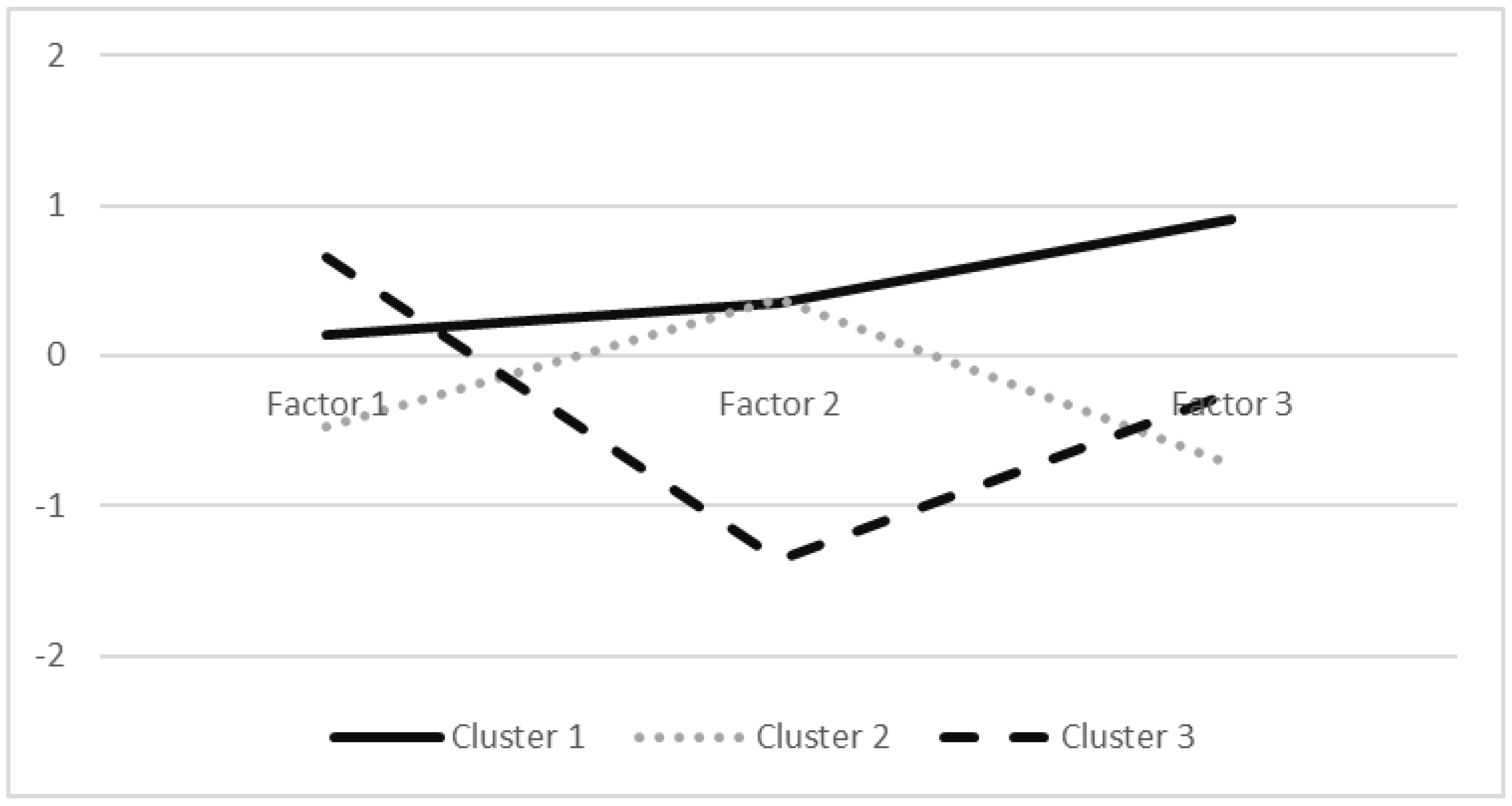

Data clustering enables citizens to be grouped according to their attitudes into three clusters. The difference is confirmed by ANOVA (

Table 5). The first cluster comprises 38.1 percent of citizens, the second 40.7 percent, and the third 21.2 percent.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between each cluster and the factors identified through factor analysis.

The first cluster comprises moderate tourism supporters. These residents exhibit a particularly strong association with Factor 3, indicating pronounced concerns regarding the sustainability of tourism development on the island. As shown in

Table 6, this group reports the highest mean values for the variables comprising Factor 3, reflecting a heightened sensitivity to issues of over-tourism, such as the perception that tourism is too large for the island’s size (mean value 3.7) and the opinion that accommodation capacity should be limited (mean value 4.4). While they moderately agree with protective measures during periods of elevated risk (Factor 1, mean values across items 3.1–3.3), their support is less pronounced than that of the risk-sensitive cluster. They recognize the developmental value of tourism for their locality (mean value 4.0) but advocate for a balanced, sustainable approach that emphasizes regulation and environmental protection alongside economic growth. Similar mixed attitudes have been documented in other small island destinations such as Cape Verde, where residents simultaneously acknowledged tourism’s economic benefits and raised concerns over social and environmental pressures [

62].

The second cluster includes tourism-oriented residents, characterized by a positive association with Factor 2 and negative associations with Factors 1 and 3. This pattern suggests strong support for tourism development, even in the face of potential external shocks such as health crises. For example, they report high agreement that tourism contributes to local development (mean value 4.6) and that both foreign (mean value 4.2) and domestic tourists (mean value 4.39) should be allowed to arrive regardless of coronavirus risk. In contrast, they express relatively low concern for restrictions (Factor 1, means between 2.0 and 2.6) or over-capacity issues (Factor 3, the mean for tourism is too large relative to the island’s size, at 2.0). Despite acknowledging that key infrastructure (e.g., water supply, healthcare) is only moderately adequate for increased tourism (mean value 2.7), these individuals maintain a favorable view of continued tourism growth and its contribution to local development (mean value 4.6). Their stance reflects a predominantly economically driven orientation, prioritizing tourism’s benefits over associated risks or sustainability concerns.

The third cluster comprises risk-sensitive residents with a strong positive association with Factor 1, a marked negative association with Factor 2, and a slight negative relationship with Factor 3. This cluster clearly prefers public health and community well-being over economic gains from tourism. They strongly agree with restrictive measures, such as monitoring arrivals (mean value 3.9), distinguishing between island and mainland tourism under pandemic conditions (mean value 3.6), and limiting accommodation capacity during high-risk periods (mean value 3.6). In contrast, they show low support for foreign arrivals (mean value 2.1) or domestic arrivals (mean value 2.5) during the period of increased risk. They advocate for restrictive measures, particularly during periods of elevated risk, and strongly agree with limiting tourist arrivals and enforcing stricter protective policies. These residents do not consider tourism a key development priority. Similar attitudes have been documented in other contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Tilaki et al. [

63] explored vendors’ attitudes in Malaysia and found a generally negative perception of international tourists during the pandemic. Likewise, this group is skeptical about the benefits of tourism and views over-tourism as a threat to the community, underscoring their belief that public health and the quality of life take precedence over the potential economic advantages of tourism expansion. Such an attitude highlights the need for more inclusive tourism planning that integrates local risk perceptions and tourism sustainability.

5. Discussion

The present research contributes to the literature on residents’ attitudes toward tourism by identifying three distinct factors and associated clusters of local citizens that capture divergent perspectives on the development of island tourism under conditions of risk and sustainability pressures. These findings resonate with, but also extend, prior research on the heterogeneity of residents’ perceptions, particularly in destinations where tourism constitutes a dominant economic sector.

The first factor and its corresponding “risk-sensitive” cluster highlight residents’ heightened concern with controlling and limiting tourism activities during health crises. This aligns with recent studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which reported a decline in tolerance towards international visitors and an increase in support for restrictive measures among local communities [

63]. Unlike earlier studies where resident attitudes were primarily structured around cost–benefit evaluations of tourism [

27], our findings reveal that health risks constitute a distinct dimension shaping tourism acceptance. However, beyond pandemics, a broader range of external shocks can also influence the attitudes of risk-sensitive residents. In addition to health-related threats, events such as natural disasters, political instability, and security concerns shape how individuals with heightened risk perception and a tendency toward protective behaviors respond to tourism. For example, Leoni and Boto-Garcia [

64] analyzed the impact of the La Palma volcano eruption on the tourism industry in the Canary Islands and found that natural disasters affect both the supply and demand sides of tourism, particularly in regions where economies are heavily dependent on the tourism sector. Farmaki [

65] examined resident perceptions in Cyprus and highlighted that geopolitical tensions and security concerns significantly influence social attitudes toward tourists within host communities, often resulting in varying degrees of acceptance or animosity depending on the political context. This suggests that residents’ attitudes cannot be explained solely through economic or environmental trade-offs but also by the perceived vulnerability of community health and safety in times of crisis.

The second factor represents a development-oriented orientation, in which residents strongly support tourism’s role in generating socio-economic benefits. This pattern has been widely documented in highly tourism-dependent destinations, where employment opportunities and improved services are often prioritized over potential negative externalities [

31,

66]. Like findings from Mediterranean islands such as Crete [

67,

68,

69], these residents exhibit a pragmatic orientation that favors the continuity of tourism, even during crisis situations [

67]. However, the relatively uncritical stance of this cluster toward infrastructural limitations raises concerns about the sustainability of growth-oriented policies, echoing prior warnings about the risks of over-dependence on tourism for local development [

52].

The third factor, emphasizing concerns about ecological carrying capacity and the disproportionate scale of tourism relative to the island’s size, aligns with the growing discourse on overtourism [

58].

This sustainability-oriented cluster shares similarities with findings from other small island contexts, such as the Azores and Cape Verde, where residents expressed dissatisfaction with unmanaged growth and called for greater regulation of visitor numbers [

62]. Our research reinforces these concerns by illustrating that, even in destinations highly dependent on tourism, a substantial proportion of residents are prepared to advocate for restrictions in pursuit of environmental protection and long-term community well-being.

The co-existence of these three clusters underscores the complexity of resident attitudes and the need to move beyond dichotomous categorizations of “supportive” versus “oppositional” communities. Our findings demonstrate that attitudes are shaped not only by economic calculations but also by risk perceptions and sustainability values. This has important implications for theoretical frameworks such as SET, which often emphasize transactional benefits. Integrating concepts of vulnerability and resilience into SET could provide a more holistic explanation of why residents support or oppose tourism under different circumstances. Practically, the findings suggest that tourism policy in small island destinations must navigate competing priorities. Development-oriented residents advocate for growth and economic stability, while risk-sensitive and sustainability-oriented groups emphasize health protection and ecological balance. Policymakers must therefore adopt participatory and adaptive approaches that recognize this heterogeneity. Failing to engage with all three perspectives risks undermining social cohesion and long-term community support for tourism development.

Participatory democracy plays a crucial role in shaping island development policy in Croatia, where local populations are increasingly recognized as key stakeholders in the sustainable management of their territories. The Croatian Islands Act (2018) marked a significant step toward decentralization and citizen involvement, mandating the inclusion of local communities in the development and implementation of island-specific strategies. Through mechanisms such as public consultations, participatory planning workshops, and local development councils, islanders are given formal channels to articulate their needs, priorities, and visions for the future. These processes aim to counteract historical top-down governance models that often overlooked the unique socio-economic and environmental realities of island life [

70]. In practice, however, the level of engagement varies significantly between islands, depending on local leadership, civil society capacity, and institutional support. While some islands, such as Vis, Hvar, and Cres, have seen successful examples of bottom-up initiatives influencing energy transitions, tourism planning, and infrastructure development, others face challenges, including administrative fragmentation and limited civic participation. Nevertheless, the growing emphasis on participatory governance reflects a broader shift towards empowering island communities as active agents in their own development, aligning with EU principles of territorial cohesion and smart island strategies.

6. Conclusions

This study provides critical insights into residents’ attitudes toward island tourism development, particularly regarding health-related crises and the imperative for sustainable development. Through factor analysis, three core dimensions of these attitudes were identified: (1) the need for protective and regulatory measures during periods of elevated health risk, (2) strong support for tourism as a driver of economic development, and (3) growing concern about the environmental and spatial limits of tourism growth. These factors reflect island communities’ complex and often conflicting views, shaped by their economic dependence on tourism and the ecological constraints inherent to insular environments.

Factor 1 reveals a risk-sensitive approach, where residents support limiting tourism during health or safety risks to protect public welfare. This dimension highlights the vulnerability of tourism-dependent economies to external shocks and disruptions. It emphasizes the need for robust tourism governance, including crisis management plans and more resilient development strategies. Even in contexts where tourism demand remains stable, this vulnerability persists, underscoring the importance of diversification and a shift toward resilience-based development models.

Factor 2 reflects a development-oriented perspective, characterized by strong support for continued growth in tourism. Residents who align with this view perceive tourism as a key driver of job creation, infrastructure improvements, and overall economic vitality. Their optimism reflects a strong confidence in the island’s capacity to accommodate future growth and aligns with pro-tourism sentiments commonly found in highly tourism-dependent regions. However, such growth-focused attitudes raise concerns about long-term sustainability, particularly in the aftermath of crises, when rebuilding efforts should consider economic recovery, public health, environmental conservation, and community well-being.

Factor 3 articulates an emerging awareness of overtourism and the limits of local carrying capacity, with residents expressing concern that tourism has exceeded acceptable thresholds relative to the island’s physical, ecological, and social dimensions. The perception that tourism must be scaled back to protect local resources, infrastructure, and quality of life reflects broader debates about the need for alternative tourism models, such as eco-tourism, slow tourism, and community-based tourism. These models prioritize environmental responsibility, social inclusion, and long-term viability, requiring strategic planning, inclusive governance, and sustainability-based policy reforms.

The findings of this study further reveal the existence of three distinct resident typologies concerning tourism development and crisis resilience: tourist-oriented, risk-sensitive, and moderate residents. This segmentation was confirmed through cluster analysis, with statistically significant differences observed among the groups.

Areas with a predominance of tourist-oriented residents demonstrate greater resilience to external shocks. These individuals view tourism as a vital economic engine and support its continued expansion, even during periods of elevated risk. Their economic optimism suggests that tourism can remain a key development pillar, provided infrastructural needs are adequately addressed.

In contrast, the risk-sensitive group exhibits high vulnerability, particularly during health-related crises. These residents advocate for strict protective measures, are skeptical of tourism’s long-term benefits, and strongly oppose relying exclusively on tourism for local development. Their preferences for regulation and diversification underscore the unsuitability of tourism as a singular development strategy and highlight the need for resilience planning and alternative economic pathways. It is essential to establish protective measures that provide risk-sensitive communities with security during crises, while simultaneously preserving the livelihoods dependent on tourism. Coordination between the government, the local business sector, and the local community is essential to ensure that these measures enhance the resilience of the tourism sector while protecting the well-being of the local community.

The moderate recognizes both tourism’s benefits and uncontrolled growth challenges. These residents support tourism development, but conditionally call for strategic regulation, sustainability, and the preservation of community well-being. Their view underscores the need for balanced tourism policies that are neither growth-centric nor overly restrictive but inclusive and adaptive to evolving challenges.

In conclusion, segmenting residents into these three clusters provides valuable guidance for policymakers and planners. This finding highlights the need to modify tourism policy to achieve a balance between short-term economic benefits derived from tourism and long-term sustainability. Tourism development strategies must move away from a one-size-fits-all approach and instead adopt context-sensitive policies that reflect local populations’ diverse levels of support, vulnerability, and expectations. Special attention must be given to building adaptive capacity in risk-sensitive communities while promoting sustainable tourism models that align with the values of both moderate and tourism-oriented residents.

Ultimately, this study underscores the fragility of current tourism development paradigms, especially in small, tourism-dependent island regions, and calls for a paradigm shift toward sustainable, resilient, and inclusive tourism frameworks. This includes limiting the overexpansion of tourism infrastructure and integrating environmental stewardship, social equity, and public health into all levels of tourism planning and policy. Such an approach is essential to ensuring the long-term viability of tourism destinations in the face of future global uncertainties. Given the divergent perspectives identified, the implementation of participatory governance, characterized by more inclusive and transparent decision-making processes, ensures that the interests of diverse stakeholders are adequately addressed and that priorities in tourism development are effectively identified and aligned.

A key limitation of this research is its focus on island communities and a restricted set of variables. Future studies would benefit from employing methodologies such as structural equation modeling on a larger and more diverse sample of residents across multiple tourism-oriented regions. It would also be valuable to examine whether, and in what ways, residents’ attitudes change over time. Furthermore, combining quantitative and qualitative methods could provide a richer understanding of the specific concerns, expectations, and values that characterize each of the identified clusters, offering deeper insights into this topic.

_Li.png)