Models of Post-Mining Land Reuse in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Models of Mine Closure and Post-Mining Land Use

2.2. Legal Regulations Concerning the Redevelopment of Post-Mining Areas

- Mining Zone (SG)—designated for lands associated with extractive activities;

- Green and Recreation Zone (SN)—applicable for reclamation through the creation of green spaces and recreational areas;

- Economic Zone (SP)—enabling the development of economic activities on post-mining land;

- Service Zone (SU)—intended for public and commercial services to support local communities.

2.3. Barriers and Challenges in Post-Mining Land Management

2.4. International Experiences and Lessons for Poland

3. Materials and Methods

- To identify the key stages and procedural models used in the mine closure process;

- To recognise barriers encountered at various stages of post-mining land redevelopment;

- To assess the extent to which the current model facilitates the integration of post-mining areas into spatial planning systems and local development strategies.

3.1. Research Question and Hypothesis

- To what extent does the current Polish model of mine closure—implemented through the operations of SRK S.A.—enable the sustainable, multifunctional, and spatially integrated reuse of post-mining land in urbanised regions such as the Upper Silesian–Zagłębie Metropolis?

- While the Polish mine closure model is procedurally effective in technical and environmental terms, it lacks institutional integration, spatial planning coordination, and stakeholder engagement, which significantly limits its capacity to support sustainable and multifunctional redevelopment of post-mining land.

3.2. Research Methods

- Archival research:A comprehensive search and analysis of archival and library materials were conducted at the Archive of Surveying and Geological Documentation of the Higher Mining Office in Katowice. The study focused on 20 decommissioned mining facilities, with an emphasis on

- Mine closure operation plans—examining both general and detailed components, along with updates to identify procedural trends;

- Mine decommissioning programmes and environmental impact assessments—assessing post-mining transformations and mitigation measures;

- Situation and land use maps—tracing spatial changes in mining sites over time.

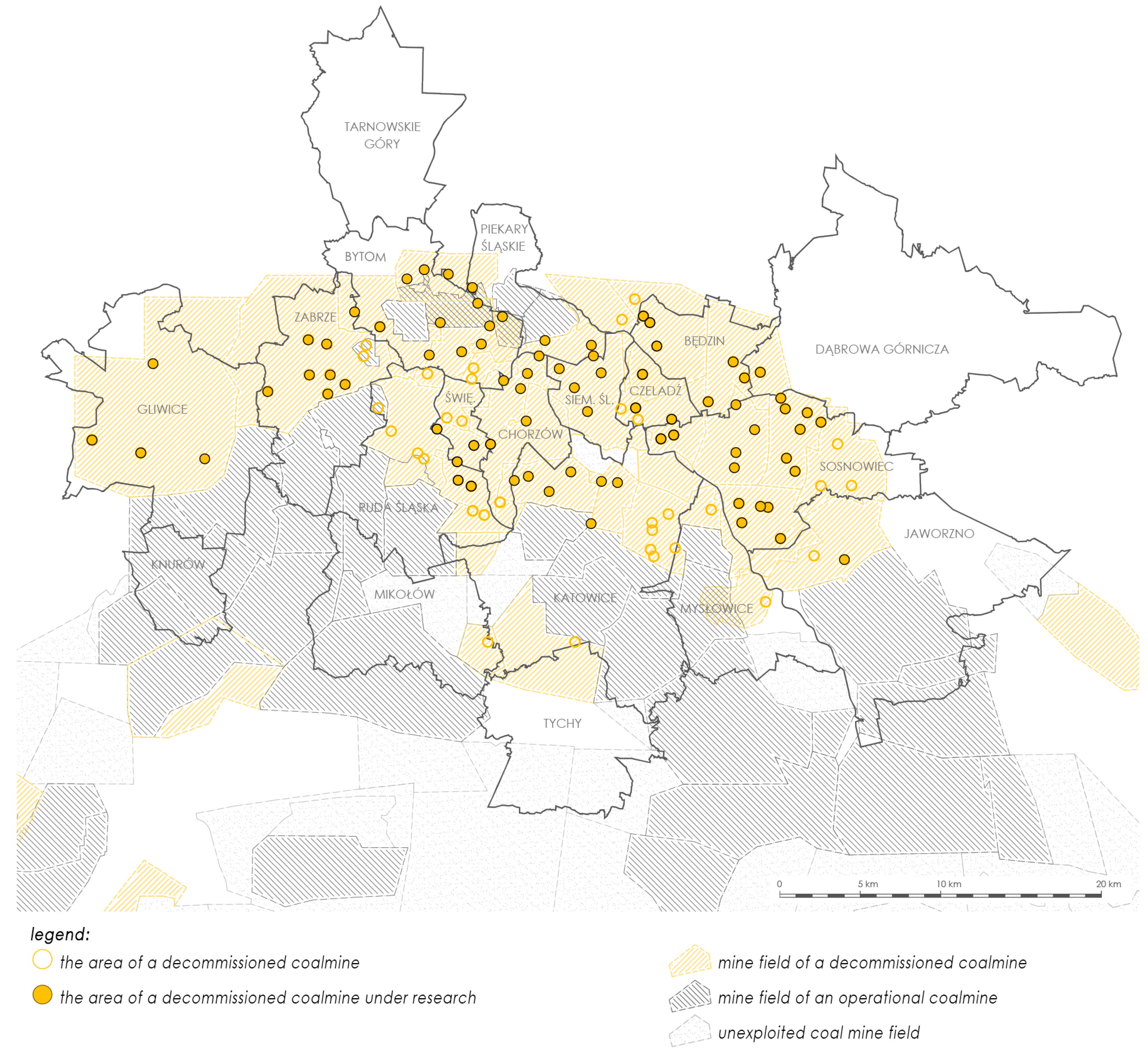

- Geodetic and cartographic data collection:To supplement the archival research, geodetic and cartographic data were collected from district offices in multiple cities across the Upper Silesian and Zagłębie Metropolis (GZM), including Bytom, Będzin, Chorzów, Czeladź, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Gliwice, Jaworzno, Katowice, Mysłowice, Piekary Śląskie, Radzionków, Ruda Śląska, Siemianowice Śląskie, Sosnowiec, Świętochłowice, and Zabrze.

- Identification and delimitation of decommissioned mining areas (1990–2019):The study was conducted on the basis of situation and elevation maps, the development of mining sites, and data collected from district geodetic and cartographic resources (Figure 1).

- Field research and visual documentation:Two phases of site visits (2020–2021 and 2024–2025) allowed for

- Identifying decommissioned mining areas through on-site verification of archival and geodetic data;

- Conducting a photographic inventory to document the current condition of post-mining landscapes and infrastructure;

- Assessing land use and the technical condition of remaining structures;

- Monitoring spatial, ownership, and usage changes in study areas over time.

- Typological classification of reuse models:Based on criteria derived from the literature on adaptive reuse and regeneration policy [3,29] and field research, the authors identified two types of transformation models:

- Model 1: Planned and coordinated redevelopment;

- Model 2: Spontaneous and market-driven adaptation.

Classification thresholds included the presence of planning instruments, stakeholder involvement, financing sources, and implementation scale. - Comparative legal and planning framework analysis:To contextualise the Polish case, a comparative analysis was conducted using selected international models: Germany, the United Kingdom, and the Czech Republic. The selection was based on

- The historical significance of hard coal mining in each country;

- Institutional diversity in managing mine closure and land reuse (e.g., state-led models vs. market-based or mixed approaches);

The comparative analysis included a review of national policies, legal frameworks, financing mechanisms, and strategic programmes (e.g., IBA Emscher Park in Germany, Coalfields Regeneration Trust in the UK, and DIAMO in the Czech Republic).

3.3. Study Area and Case Selection

- Areas which, according to valid closure plans, were fully operated as mining plants and whose documentation was owned by restructuring companies (Coal Mine “Śląsk”, Coal Mine “Wieczorek”, Coal Mine “Boże Dary”, Coal Mine “Mysłowice”, Coal Mine “Pokój”);

- Areas of active mining plants, which are private enterprises using the sites of closed mines for their operations (Mine “Siltech”);

- Landfills, dumps, slag heaps, subsidence areas, reservoirs, peripheral shafts, and other facilities typically located outside the main plant area, which were not technically and organisationally separated according to the adopted definition of a mining plant area.

4. Results

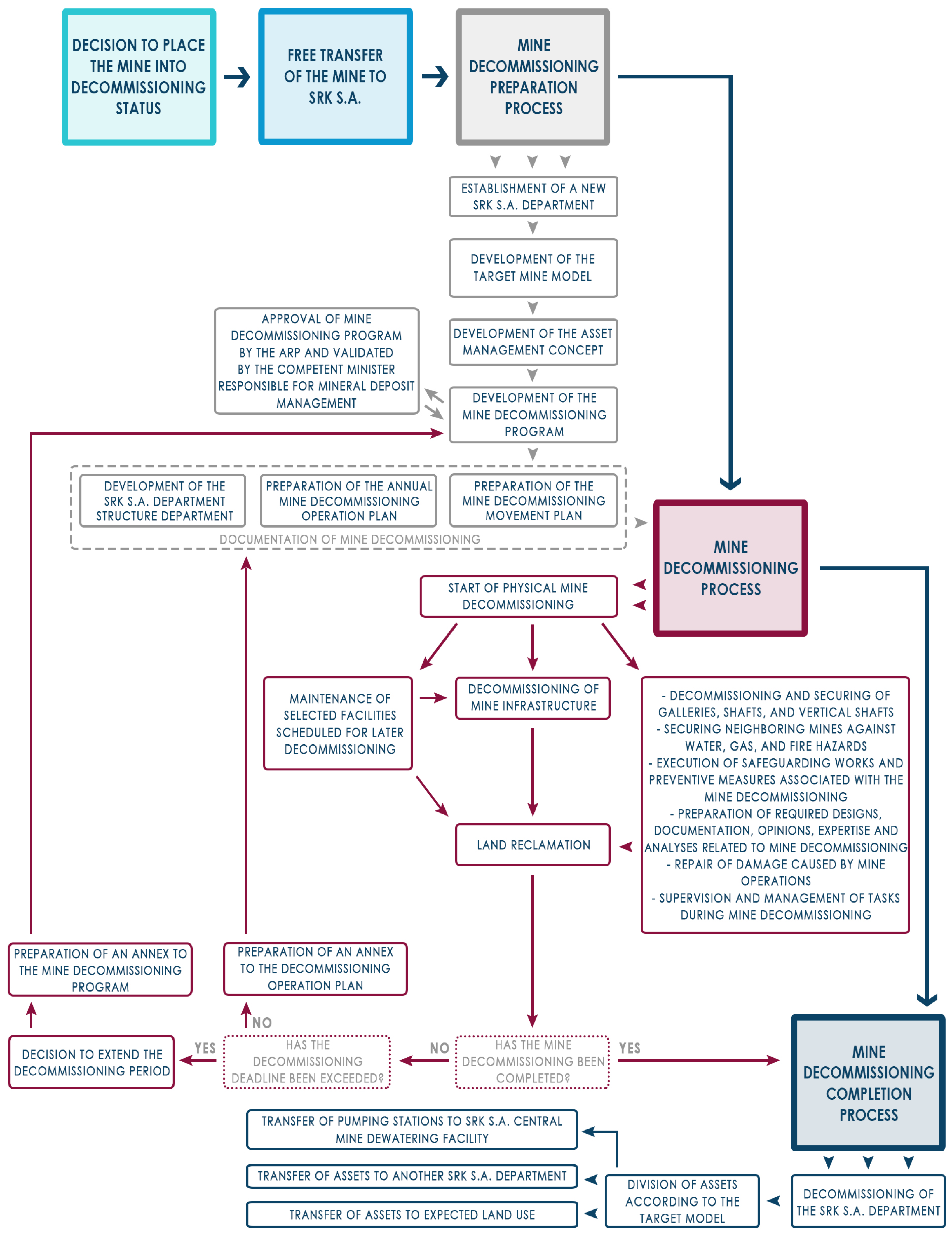

4.1. Mine Decommission Management Model—Formal Conditions

- Stage I—decision to place the mine into decommissioning status;

- Stage II—free transfer of the mine to the Mine Restructuring Company (SRK S.A.);

- Stage III—preparatory process for mine decommissioning;

- Stage IV—execution of mine decommissioning;

- Stage V—completion of mine decommissioning and initiation of land reuse (Figure 3).

- Conducting mine closure operations and securing adjacent mining facilities against water, gas, and fire hazards;

- Remediating mining damage and reclaiming post-mining areas;

- Managing assets, selling real estate from liquidated mining facilities, and supporting the creation of new jobs, particularly for employees of closed mines.

- Retaining certain buildings and infrastructure based on the future operational model;

- Transferring selected buildings or land for sale;

- Dismantling structures and infrastructure that lack potential for future reuse [83].

- The preparation of required projects, documentation, opinions, expert reports, and analyses related to mine closure;

- The closure and securing of underground workings, shafts, and boreholes;

- The protection of adjacent mines from water, gas, and fire hazards;

- The execution of protective measures and preventive actions associated with the closed mining facility;

- The repair of damages caused by mining operations;

- The management and supervision of all activities throughout the mine closure process [83].

- Normal transfer of the closed mine’s assets to another SRK SA branch or the Central Mine Dewatering Plant (CZOK) of SRK SA, ensuring protection of adjacent mines from water, gas, and fire hazards;

- Sale or transfer of the land to a new owner;

- Management and supervision of all activities throughout the mine closure process [83].

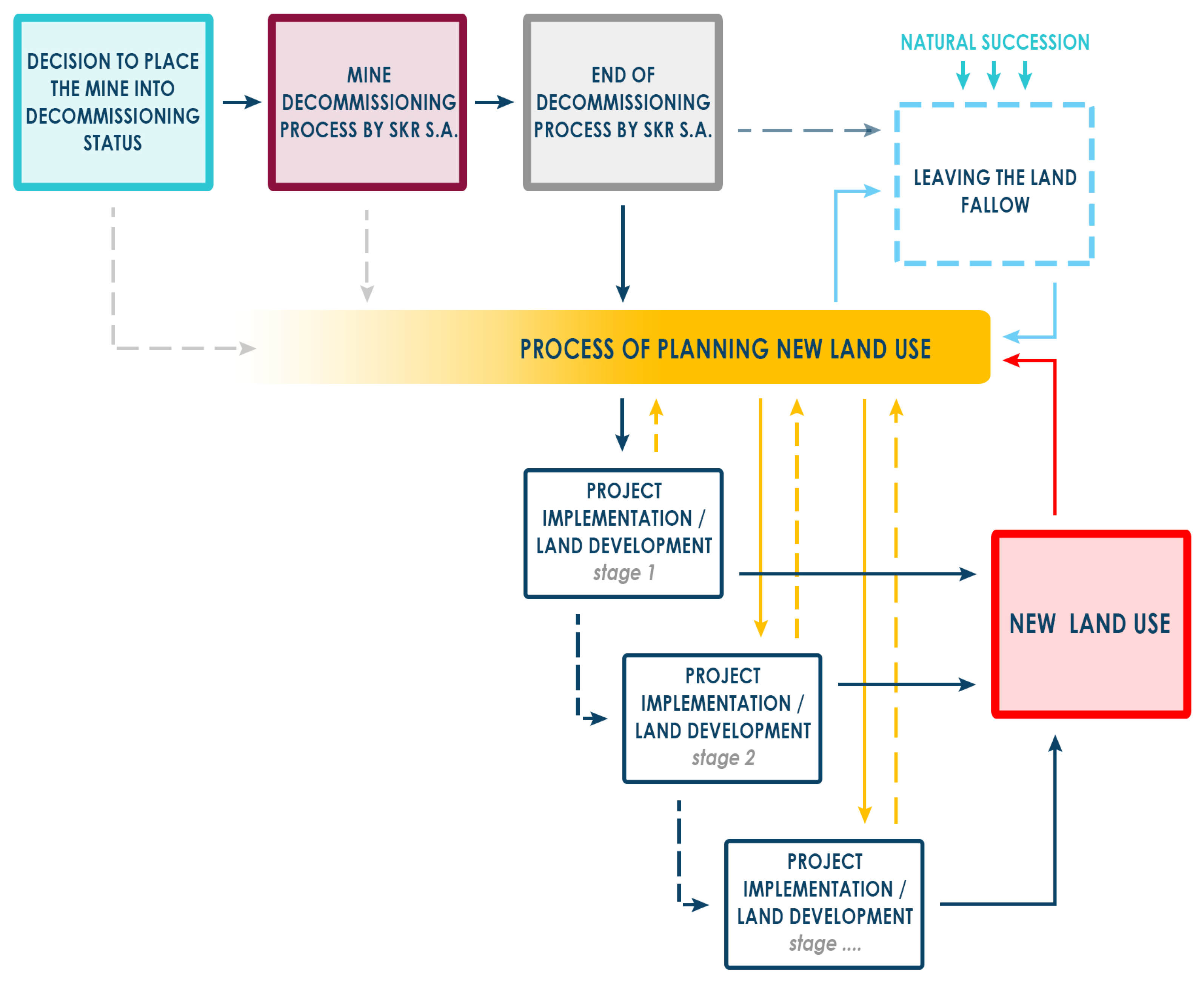

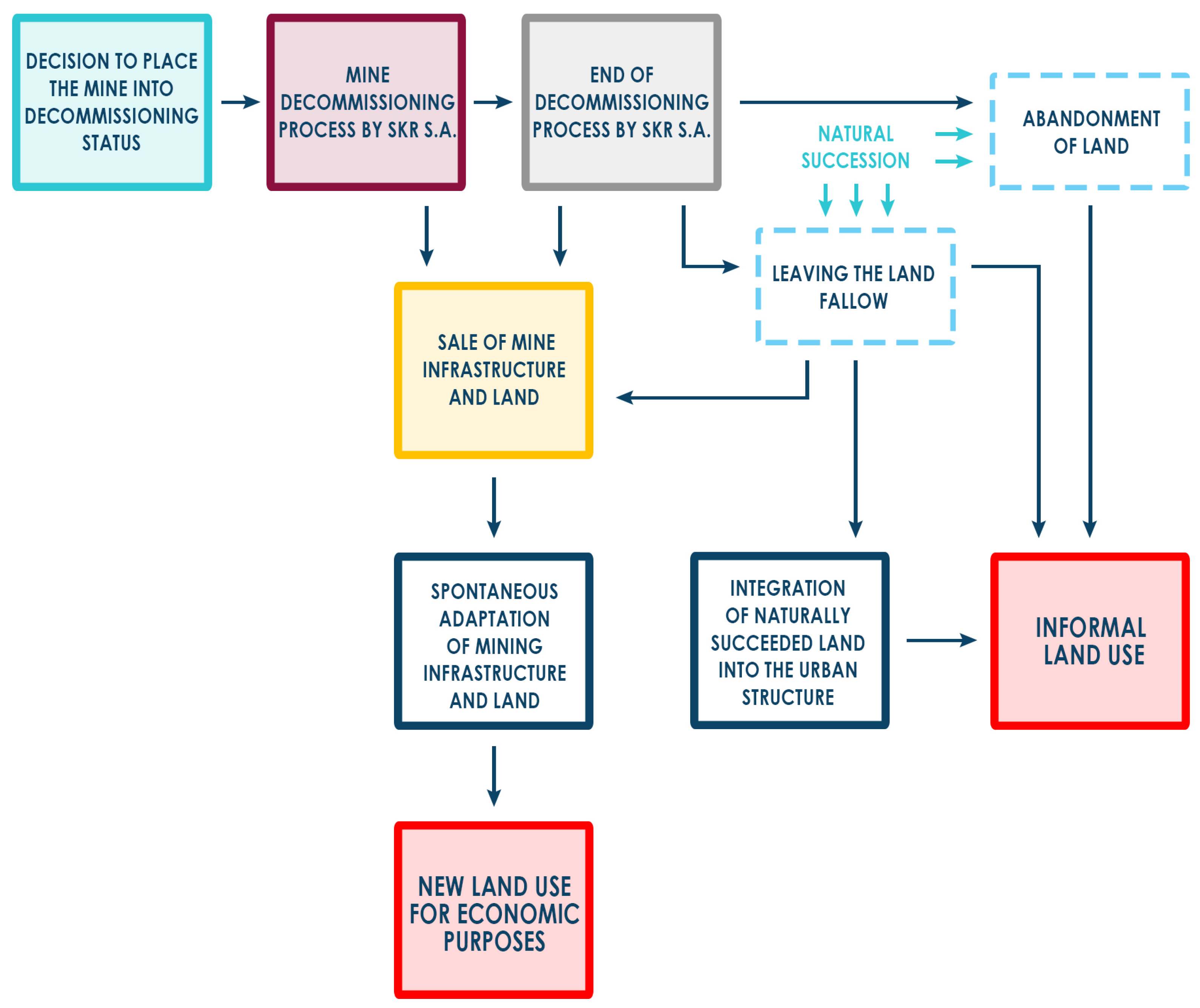

4.2. Models for the Reuse of Post-Mining Land

- Stage I—decommissioning of the mining facility and basic land reclamation;

- Stage II—planning the transformation;

- Stage III—implementation of the planned transformation;

- Stage IV—reuse of the land.

- The method of managing the facility’s closure (as previously described);

- The sale or transfer of the mining facility’s assets to a new owner (private or public);

- The investment goals of the new owner;

- The size and location of the area;

- Applicable legal regulations and available funding sources (public funds, EU funding, private investment).

- Model 1—Planned and coordinated redevelopment: In this model, the transformation process is meticulously planned, based on detailed analyses and spatial development strategies.

- Model 2—Spontaneous and market-driven adaptation: Within the framework of this model, post-mining areas transform spontaneously, driven by the immediate needs of investors and local stakeholders or due to a lack of intervention. This model allows quicker investment realisation but carries the risk of leaving land unmanaged and underutilised.

4.2.1. Model 1—Planned Land Reuse and Coordinated Redevelopment

4.2.2. Model 2—Unplanned (Spontaneous) Land Reuse and Market-Driven Adaptation

4.2.3. Strengths and Weaknesses of Management and Reuse Strategies for Post-Mining Land in Poland

5. Discussion

5.1. Evaluation of Existing Hard Coal Mine Closure Models

| Country/Phases | Poland | Germany | United Kingdom | Czech Republic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision to close | Based on unprofitability, resource depletion, or environmental reasons. | Strategic government and industry decision, supported by energy transition policy. | Government decisions supported by economic and environmental analyses. | Decisions made by state-owned companies, often linked to resource depletion and EU requirements. |

| Entity responsible for closure | Hard Coal Restructuring Company (SRK) until 2023; thereafter, mining companies. | RAG AG—company responsible for closure and reclamation. | Coal Authority—government agency. | DIAMO—state-owned company managing closure and reclamation of post-mining areas. |

| Planning and preparation | Development of a technical–economic closure plan, reclamation, and repurposing of assets. | Integrated planning encompassing environmental, social, and technical aspects. | Detailed technical and environmental audits. | Closure documentation approved by the Ministry of Industry and Environment. |

| Key closure stages |

|

|

|

|

| Financing | Mine closure fund; previously SRK with public assistance. | Industry funds + government grants (multi-year agreements) and state-level funds. | Public funds + environmental funds. | State budget and EU funds (e.g., Just Transition Fund). |

| Post-closure land management | Transfer of land to new owner and designation of new functions. | Long-term monitoring, transformation to new functions (e.g., recreation, industry). | Oversight of risks (landslides, contamination), transformation. | Utilisation for industrial, agricultural, or recreational purposes. |

5.2. Analysis of Barriers and Challenges in Mine Closure and Post-Mining Land Reclamation in Poland

- Legal Barriers—The absence of unified regulations comprehensively governing the mine closure process and post-mining land reclamation, considering spatial planning, social, and environmental aspects; existing legal acts primarily focus on technical closure aspects, neglecting integrated revitalisation planning or protection of industrial heritage; interpretative ambiguities regarding regulations on post-mining land ownership, the possibility of transferring them to municipalities, and liability for mining damages significantly delay investment processes [98,99].

- Administrative Barriers—Complexity of administrative procedures, limited coordination, and fragmentation of competences among authorities (e.g., SRK, local government units, environmental protection agencies, mining supervision, ministries); lengthy waiting times for environmental and planning decisions; lack of a dedicated institution responsible for managing the process of post-mining land reclamation, leading to dispersed responsibility and inefficient actions [57]; insufficient staffing and expert resources with adequate knowledge and experience to manage complex post-mining transformations and coordinate inter-institutional actions [29].

- Financial Barriers—Insufficient financial resources allocated for mine closure and land transformation, as obtaining them depends on SRK’s budgetary capabilities and access to EU funds (e.g., Just Transition Fund); after 2023, the responsibility for financing the process lies with mining companies, leading to slowed closures, especially for less profitable mines [100]; lack of long-term financial instruments and effective mechanisms for attracting investors supporting the transformation of post-mining areas tailored to local needs [101,102].

- Social Barriers—In many mining regions, the transformation process is perceived as a threat to local identity and economic stability; high unemployment rates, lack of qualifications for work in other sectors, and social resistance to change; low trust in authorities and a deficit of public participation mechanisms (social consultations are often formal and limited) in spatial planning hinder building social acceptance for revitalisation projects [103]; failure to recognise the historical, scientific, and cultural value of mining heritage sites and the investment potential of post-mining areas [29,104].

- Economic Barriers—High competitiveness of similar sites within the same region, stemming from their location, resource accessibility, or infrastructure availability [3,105,106]; limited investor interest results in prolonged economic stagnation [4,107]; insufficient capacity to secure external financial support, such as from regional operational programmes or funding for heritage protection and cultural development, due to concerns about hidden infrastructure (e.g., foundations, pipelines, tunnels, tanks) and site contamination, which may substantially increase the cost of redevelopment [29].

- Environmental Barriers—The closure of mines is often associated with a range of negative environmental impacts, including land subsidence, contamination of groundwater, and the presence of heavy metals and toxic gases. The absence of funding for long-term environmental monitoring significantly affects the ability to safely repurpose post-mining land [108]. Without ongoing assessment, these areas may pose enduring risks to public health and environmental quality.

- Spatial Barriers—Many post-mining sites are characterised by a lack of functional and spatial coherence with surrounding urbanised areas. This includes proximity to heavily urbanised residential–industrial complexes or isolation from dynamically developing urban centres, as well as positioning along major railway lines. These spatial discontinuities present major challenges for effective spatial planning [29], particularly in the absence of up-to-date local land use plans and due to discrepancies between strategic documents and actual socio-economic needs [106]. Additional challenges include limited land availability and conflicts between public and private interests, as well as difficulties in adapting degraded areas for new urban functions [109].

- Temporal Barrier—Unutilised post-mining areas are subject to natural degradation over time. This gradual decline in the technical condition of mining infrastructure, coupled with spontaneous ecological succession, contributes to rising redevelopment costs for potential investors [106]. Consequently, such areas are often categorised as problematic legacy sites rather than assets with spatial reuse potential [29], further exacerbating their marginalisation in regional development strategies.

5.3. Recommendations and Proposed Directions for Reform in Mine Closure and Post-Mining Land Management

- Legal Barriers—Recommendations

- Develop a coherent legislative framework for post-mining areas. There is currently no dedicated law regulating the transition and reuse of post-mining land. It is recommended that Poland consider enacting legislation analogous to the Revitalisation Act, specifically tailored to post-mining transformation.

- Clarify obligations of mining companies. Establish clear transitional and implementing regulations to define the responsibilities of mining enterprises under the new financing principles related to mine closure, particularly with respect to the use of closure funds.

- Administrative Barriers—Recommendations

- Appoint a regional post-mining transformation coordinator. Effective integration of the efforts of local governments, the Mine Restructuring Company (SRK), the State Mining Authority (WUG), investors, and civil society organisations requires institutional coordination at the regional level.

- Create a national post-mining land registry. Establish a comprehensive database integrating information on land status, ownership structure, environmental burdens, and development potential to support informed planning and investment decisions.

- Financial Barriers—Recommendations

- Ensure long-term funding for post-mining transformation. Sustainable transformation requires stable financing, including continued access to the Just Transition Fund and complementary national instruments such as the National Fund for the Revitalisation of Post-Industrial Areas.

- Support local governments in investment preparation. Develop pre-financing mechanisms for feasibility studies, environmental assessments, and spatial planning documentation to overcome entry barriers for public and private investment.

- Social Barriers—Recommendations

- Strengthen public participation in the transition process. Establish local transformation councils, organise inclusive public consultations, and create dialogue platforms to co-design new land uses and identify local needs.

- Provide psychosocial and vocational support for mining communities. Invest in reskilling and coaching programmes, career development services, and initiatives aimed at preventing social exclusion in deindustrialising regions.

- Economic Barriers—Recommendations

- Introduce investment incentives for post-mining sites. Offer tax relief for investors operating in reclaimed areas, particularly those aligned with green economy sectors and knowledge-based industries.

- Support local SMEs in post-mining regions. Expand support programmes to include components specifically targeting green transformation and diversification in local economies.

- Environmental Barriers—Recommendations

- Standardise environmental assessments for post-mining lands. Require mandatory environmental impact assessments for sites intended for redevelopment and integrate them into planning frameworks.

- Implement long-term post-closure environmental monitoring. Establish a system to monitor groundwater quality, land subsidence, methane emissions, and secondary contamination, financed through dedicated mine closure funds.

- Include blue–green infrastructure functions and urban climate adaptation objectives in post-mining land redevelopment plans.

- Prioritise nature-based solutions and investments in renewable and low-emission infrastructure within former mining areas.

- Integrate EU climate and adaptation policy goals into local and regional post-mining land revitalisation strategies.

- Spatial Barriers—Recommendations

- Enhance spatial planning flexibility. Adapt spatial policies to dynamic social, economic, and environmental conditions by allowing for interim or phased land uses in transition zones.

- Spatial—the extent and quality of reclaimed and reused land;

- Economic—the increase in jobs and revenue generated by new uses;

- Social—preservation of local identity and protection of industrial heritage;

- Environmental—restoration of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

- Success Factors:

- Long-term planning based on a thorough assessment of local community needs;

- Strong political and financial backing;

- An interdisciplinary approach integrating spatial, social, economic, and environmental dimensions;

- Active engagement of local stakeholders.

- Failure Factors:

- Lack of a coherent redevelopment vision;

- Conflicts of interest between investors and the local population;

- Underestimation of costs and environmental risks;

- Absence of post-project monitoring and evaluation.

6. Conclusions

- Long-term planning embedded in local and regional spatial development strategies;

- Stable and predictable financing for both closure and revitalisation processes;

- Genuine engagement of residents, local governments, non-governmental organisations, and experts in the planning and implementation of projects.

- Strengthen the integration of strategic and spatial planning activities;

- Establish a national institution to coordinate mine closure and revitalisation efforts;

- Improve access to funding at the local level;

- Adapt participatory mechanisms to enable the broad involvement of diverse social groups.

- Evaluation of the long-term socio-economic impacts of post-mining transformations;

- Spatial analysis of transformation outcomes, using GIS and environmental data to identify areas at risk of marginalisation or degradation;

- Studies on participatory mechanisms and their influence on revitalisation success, including the role of local leaders, civil society organisations, and municipalities;

- Cross-regional and cross-national comparisons to develop best practices adaptable to the Polish context;

- Conflict management during transformation, with emphasis on developing mediation and planning tools.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pytel, S.; Sitek, S.; Chmielewska, M.; Zuzańska-Żyśko, E.; Runge, A.; Markiewicz-Patkowska, J. Transformation Directions of Brownfields: The Case of the Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivinen, S. Post-Mining Land Use: Are Closed Metal Mines Abandoned or Re-Used Space? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasidło, K. Problemy przekształceń terenów poprzemysłowych. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śl. Ser. Archit. 1998, 37. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=7681 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Wirth, P.; Černič Mali, B.; Fischer, W. (Eds.) Post-Mining Regions in Central Europe: Problems, Potentials, Possibilities; Oekom Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://content-select.com/en/portal/media/view/52e695f6-c180-4192-906f-2f4f2efc1343 (accessed on 28 June 2025)ISBN 978-3-86581-500-2.

- Ostręga, A. Organizacyjno-Finansowe Modele Rewitalizacji w Regionach Górniczych; Wydawnictwa AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2013; Available online: https://winntbg.bg.agh.edu.pl/skrypty4/0637/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Nadrowska, M. Programy odnowy tradycyjnych regionów przemysłowych. Doświadczenia Niemiec. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śl. Ser. Archit. 2006, 44, 109–115. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/publication/36419/edition/32698 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Buława, B. Rozwój Modelu Przekształceń Terenów Zdegradowanych na Przykładzie Międzynarodowej Wystawy Budowlanej w Niemczech. Ph.D. Thesis, Politechnika Śląska, Gliwice, Poland, 2010. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/publication/4737 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Pinch, P.; Adams, N. The German Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) and Urban Regeneration: Lessons from the IBA Emscher Park. In The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration; Leary, M.E., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; Chapter 19. [Google Scholar]

- Didier, C.; Bonneviale, P.; Guise, Y. Closing Down and Securing Underground Mining Works in France. Legal and Technical Aspects. In Proceedings of the Conférence “L’Exploitation Minière et l’Environnement”, Sudbury, ON, Canada, 13–15 September 1999; pp. 819–828. [Google Scholar]

- Helfer, M. The Legacy of Coal Mining—A View of Examples in France and Belgium. In Boom–Crisis–Heritage: King Coal and the Energy Revolutions After 1945; Bluma, L., Farrenkopf, M., Meyer, T., Eds.; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Loginova, J.; Zhang, R.; Kemp, D.; Shi, G. How Do Past Global Experiences of Coal Phase-Out Inform China’s Domestic Approach to a Just Transition? Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 2059–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, F.M.; Rud, J.P.; Toews, G. Resource Shocks, Employment, and Gender: Evidence from the Collapse of the UK Coal Industry. Labour Econ. 2018, 52, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokół, W. Metodologia Zarządzania Terenami Poprzemysłowymi z Wykorzystaniem Ekoefektywnych Technologii środowiskowych; Główny Instytut Górnictwa: Katowice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Paszcza, H. Procesy restrukturyzacyjne w polskim górnictwie węgla kamiennego w aspekcie zrealizowanych przemian i zmiany bazy zasobowej. Górnictwo I Geoinżynieria 2010, 34, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Korski, J.; Tobór-Osadnik, K.; Wyganowska, M. Reasons of Problems of the Polish Hard Coal Mining in Connection with Restructuring Changes in the Period 1988–2014. Resour. Policy 2016, 48, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbownik, A.; Bijańska, J. Restrukturyzacja Polskiego Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Latach 1990–1999; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kopalnie w Polsce—Aktualizacja 2024. Available online: https://instrat.pl/kopalnie-w-polsce-aktualizacja-2024/ (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Kicki, J. (Ed.) Raport 2020. Górnictwo Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce; Instytut Gospodarki Surowcami Mineralnymi i Energią PAN: Kraków, Poland, 2021; Available online: https://min-pan.krakow.pl/.../Raport-2020_Górnictwo-węgla-kamiennego-w-Polsce.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Lis, M.; Kotelska, J. Restrukturyzacja Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego w Polsce w Perspektywie Oceny Interesariuszy; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii WSB: Dąbrowa Górnicza, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Spółka Restrukturyzacji Kopalń SA. Available online: https://srk.com.pl/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Baza Demograficzna. Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa, Poland. Available online: https://demografia.stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Szpor, A.; Ziółkowska, K. The Transformation of the Polish Coal Sector; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agencja Rozwoju Przemysłu S.A. Available online: https://arp.pl/pl/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Hamerla, A. Tereny pogórnicze i poprzemysłowe inne niż pogórnicze w systemie OPI-TPP 2.0. In Presentation; Główny Instytut Górnictwa: Katowice, Poland, 2021; (unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Koj, J. Potencjał i kierunki wykorzystania terenów poprzemysłowych w GZM. In Presentation; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Kraków, Poland, 2021; (unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Wyrzykowska, A. The Land Use of Decommissioned Coal Mines Areas in the Upper Silesian Agglomeration (Poland). Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2022, 16, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogólnodostępna Platforma Informacji Tereny Poprzemysłowe i Zdegradowane. Available online: https://opitpp.gig.eu/celerezultaty.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- OPI-TPP 2.0: Rozbudowa Systemu Zarządzania Terenami Pogórniczymi na Terenie Województwa śląskiego. Available online: https://opi-tpp2.pl/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Wyrzykowska, A. Przekształcenia Przestrzenne Zlikwidowanych Zakładów Górniczych Węgla Kamiennego na Terenie Aglomeracji Górnośląskiej. Ph.D. Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Gliwice, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution A/RES/70/1, United Nations General Assembly, 25 September 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- European Commission. Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; Communication COM(2010) 2020 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 3 March 2010; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52010DC2020 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- United Nations. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. How to Measure Distance to SDG Targets Anywhere; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/10/how-to-measure-distance-to-sdg-targets-anywhere_b55c20fe/a0ac1413-en.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Frantál, B.; Frajer, J.; Martinát, S.; Brisudová, L. The curse of coal or peripherality? Energy transitions and the socioeconomic transformation of Czech coal mining and post-mining regions. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2022, 30, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Cheng, Z.; Ai, K.; Shang, B. Research on Environmental Sustainability of Coal Cities: A Case Study of Yulin, China. Energies 2020, 13, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z Dnia 27 Marca 2003 r. o Planowaniu i Zagospodarowaniu Przestrzennym, Dz.U. 2003 nr 80 poz. 717; Aktualizacja tj. Dz.U. 2024 poz. 1130. Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/.../17027058 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Keenan, J.; Holcombe, S. Mining as a temporary land use: A global stocktake of post-mining transitions and repurposing. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, J. Rekultywacja terenów pogórniczych w Polsce. Zesz. Probl. Postępów Nauk Rol. 1995, 418, 75–86. Available online: https://agro.icm.edu.pl/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Zhengfu, B.; Inyang, H.I.; Daniels, J.L.; Frank, O.; Sue, S. Environmental issues from coal mining and their solutions. Min. Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dołzbłasz, S.; Mucha, P. Wykorzystanie terenów pogórniczych na przykładzie Wałbrzycha. Stud. Miej. 2015, 17, 106–118. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Guan, Q.; Zuo, R.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y. Temporal and spatial changes of land use and landscape in a coal mining area in Xilingol grassland. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Energy Engineering and Environmental Protection (EEEP 2016), Sanya, China, 21–23 November 2016; Volume 52, p. 012052. [Google Scholar]

- Svobodova, K.; Owen, J.R.; Harris, J. The global energy transition and place attachment in coal mining communities: Implications for heavily industrialized landscapes. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measham, T.; Walker, J.; Haslam McKenzie, F.; Kirby, J.; Williams, C.; D’Urso, J.; Littleboy, A.; Samper, A.; Rey, R.; Maybee, B.; et al. Beyond closure: A literature review and research agenda for post-mining transitions. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, S.; Svobodova, K.; Côté, C.; Bolz, P. Regional post-mining land use assessment: An interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, R.; Frantál, B.; Klusáček, P.; Kunc, J.; Martinat, S. Factors affecting brownfield regeneration in post-socialist space: The case of the Czech Republic. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczuk, A.; Sekuła, A.; Miszczuk, M. Zielona Transformacja Gospodarki i Finansów Samorządowych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://www.dbc.wroc.pl/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Li, G.; Hu, Z.; Li, P.; Yuan, D.; Wang, W.; Han, J.; Yang, K. Optimal layout of underground coal mining with ground development or protection: A case study of Jining, China. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jureczka, J.; Galos, K. Niektóre aspekty ponownego zagospodarowania wybranych złóż. In Polityka Energetyczna; Polityka Energetyczna: Kraków, Poland, 2007; Volume 10, pp. 645–661. [Google Scholar]

- Petrova, S.; Marinova, D. Social impacts of mining: Changes within the local social landscape. Rural Soc. 2013, 22, 3350–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najwyższa Izba Kontroli. Analiza Procesu Likwidacji Kopalń w Polsce. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Kozińska, M. Koncepcja rekultywacji i zagospodarowania części terenu po byłej Kopalni Węgla Kamiennego „Niwka” w Sosnowcu. Przegląd Bud. 2013, 3, 82–85. Available online: https://www.przegladbudowlany.pl/... (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Mhlongo, S.E. Evaluating the post-mining land uses of former mine sites for sustainable purposes in South Africa. J. Sustain. Min. 2023, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobniak, A.; Ochojski, A.; Churski, P.; Muster, R.; Zakrzewska-Półtorak, A.; Baron, M.; Rzeńca, A.E.; Trembaczowski, Ł.; Korenik, S.; Rynio, D.; et al. Rekomendacje strategiczne dla sprawiedliwej transformacji w Polsce. In Sprawiedliwa Transformacja Regionów węGlowych w Polsce. Impulsy, Konteksty, Rekomendacje Strategiczne; Drobniak, A., Ed.; Wyd. Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2022; pp. 130–218. Available online: https://sbc.org.pl/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Biały, W.; Midor, K. Problemy gminy przy rewitalizacji terenów pogórniczych. Syst. Wspom. W Inż. Prod. 2021, 10, 1–10. Available online: http://www.stegroup.pl/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Palka, K.; Biały, W. Perspektywy rekultywacji terenów pogórniczych na obszarze miasta Bohumin – studium przypadku. Syst. Wspom. W Inż. Prod. 2015, 3, 142–151. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Ostręga, A.; Łacny, Z.; Kowalska, N.; Preidl, K. Rekultywacja, zagospodarowanie i rewitalizacja terenów pogórniczych — przegląd doświadczeń Wydziału Górnictwa i Geoinżynierii. Przegląd Górniczy 2019, 75, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sorychta-Wojsczyk, B. Model zagospodarowania majątku likwidowanej kopalni węgla kamiennego w gminie górniczej. Zeszyty Naukowe. Organizacja i Zarządzanie, Politechnika Śląska. 2005, pp. 265–279. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/... (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Sorychta-Wojsczyk, B. Model Zagospodarowania Majątku Likwidowanych Kopalń Węgla Kamiennego; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lorek, A. Jak prawidłowo kształtować relacje gmin z inwestorami? Analiza na przykładzie zintegrowanego planu inwestycyjnego i umowy urbanistycznej. Młoda Palestra–Czasopismo Apl. Adwokackich 2024, 3, 96–107. Available online: https://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.ojs-issn-2451-327X-year-2024-issue-3-article-8dc23de6-e400-3350-ad13-d88c7478a45a (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Daniel, P.; Kafar, D.; Pawlik, K. Systemowe zmiany w planowaniu przestrzennym, seria Prawo w Praktyce, Wydawnictwo C.H. Beck, Warszawa 2023, ss. 138, ISBN: 978-83-8356-052-6. Stud. Prawa Publicznego 2024, 2, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noworół, A. Strategia rozwoju lokalnego w warunkach globalnej niepewności oraz zmian prawnych i technologicznych. Rozwój Regionalny i Polityka Regionalna 2024, 70s, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, E.; Szewczyk, M. Plan ogólny-nowy (stary) instrument planowania przestrzennego. In E-Monografie; nr 217; Prace Naukowe WPiAE Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, E. Planowanie przestrzenne na poziomie lokalnym: Powiązanie teorii z praktyką. In Studia Komitetu Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju PAN; Polska Akademia Nauk, Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; Volume 15/207, ISBN 978-83-66847-38-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, M. Strategia rozwoju gminy jako główne narzędzie służące do prowadzenia polityki rozwoju–analiza wybranych zagadnień. Stud. Prawa Publicznego 2024, 4, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P. Znaczenie strategii rozwoju w procesie integracji planowania strategicznego i przestrzennego. In Współczesne Wyzwania Zarządzania Samorządem Lokalnym–Analiza Wieloaspektowa; Czopek, M., Walczak, J., Eds.; Grupa Wydawnicza PNCE: Poznań, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Uszkur, A. Plan zagospodarowania przestrzennego województwa jako narzędzie realizacji inwestycji celu publicznego o znaczeniu ponadlokalnym. Urban Dev. Issues 2024, 75, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, M.; Stańczak, L.; Ricketts, B. Just transition of post mining areas–technical, economic, environmental and social aspects. Min. Mach. 2023, 41, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z Dnia 9 Czerwca 2011 r. Prawo Geologiczne i górnicze, Dz.U. 2011 nr 163 poz. 981, art. 126. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20111630981 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Siedlecka, E.; Cieślak, A. Rozwiązania rekultywacji zdegradowanych terenów pokopalnianych. Inżynieria środowiska I Biotechnol. I Nowe Technol. 2023, 1, 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Kołsut, B. Główne problemy i wyzwania rewitalizacji miast w Polsce. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2017, 39, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralak, K. Instrumenty finansowania lokalnych projektów rewitalizacyjnych. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW, Polityki Eur. Finans. I Mark. 2010, 4, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacławik, B. Instrumenty finansowe w procesie rewitalizacji terenów poprzemysłowych w warunkach polskich. Probl. Rozw. Miast 2013, 10, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziński, C. Polityka Przestrzenna w Polsce. Instytucjonalne Uwarunkowania na Poziomie Lokalnym i Jej Skutki Finansowe; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Wang, J.; Jing, Z.; Liu, B. Identification and management of land use conflicts in mining cities: A case study of Shuozhou in China. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. An overview of land use conflicts in mining communities. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Cotella, G.; Śleszyński, P. The legal, administrative, and governance frameworks of spatial policy, planning, and land use: Interdependencies, barriers, and directions of change. Land 2021, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberman, R.; Ostręga, A. Reclamation and revitalisation of lands after mining activities: Polish achievements and problems. AGH J. Min. Geoeng. 2012, 36, 285–297. Available online: https://journals.bg.agh.edu.pl/MINING/2012.36.2/mining.2012.36.2.285.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Kasztelewicz, Z. Approaches to post-mining land reclamation in Polish open-cast lignite mining. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2014, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jąderko-Skubis, K. Wspomaganie zarządzania terenami pogórniczymi w województwie śląskim–analiza wybranych elementów systemu OPI-TPP 2.0. In Innowacyjna Zielona Gospodarka. Nowe Horyzonty dla Ekoinnowacji Część 5; Kruczka, M., Ed.; Główny Instytut Górnictwa: Katowice, Poland, 2023; pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pagouni, C.; Pavloudakis, F.; Kapageridis, I.; Yiannakou, A. Transitional and post-mining land uses: A global review of regulatory frameworks, decision-making criteria, and methods. Land 2024, 13, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marot, N.; Harfst, J. Post-mining landscapes and their endogenous development potential for small- and medium-sized towns: Examples from Central Europe. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiela, A. Procesy restrukturyzacji i rewitalizacji kopalń postawionych w stan likwidacji. Systemy Wspomagania w Inżynierii Produkcji 2022, 11, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Hou, W.; Chang, J. Changing coal-mining brownfields into green infrastructure: Ecological potential assessment in Xuzhou, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H. Urban Resilience through Design: A Holistic Framework for Sustainable Redevelopment of Brownfield Sites. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materna, A.; Theuner, J.; Knippschild, R.; Barrett, T. Regional Design for Post-Mining Transformation: Insights from Implementation in Lusatia. Plan. Pract. Res. 2024, 39, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrychová, M.; Svobodova, K.; Kabrna, M. Mine reclamation planning and management: Integrating natural habitats into post-mining land use. Resour. Policy 2020, 69, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, E.; Clark, I.; Rossiter, W. Local economic governance strategies in the UK’s post-industrial regions. Local Econ. 2021, 36, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z Dnia 7 Września 2007 r. o Funkcjonowaniu Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego, Dz.U. 2007 nr 192 poz. 1379, z późn. zm. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20071921379 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Oei, P.-Y.; Brauers, H.; Herpich, P. Lessons from Germany’s hard coal mining phase-out: Policies and transition from 1950 to 2018. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Loo, S.; Brüggemann, R. Post-Mining Research on Reactivation and Transition. Min. Rep. Glückauf 2021, 157, 305–312. Available online: https://mining-report.de/english/post-mining-research-on-reactivation-and-transition/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Heffron, R.J.; McCauley, D. What is the ‘Just Transition’? Geoforum 2018, 88, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Territorial Just Transition Plans. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2021/the-territorial-just-transition-plans (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Coal Authority. Annual Report and Accounts 2020–21. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-coal-authority-annual-report-and-accounts-2020-2021 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Hard Coal Restructuring Company. Zasady Funkcjonowania i Zadania SRK. Available online: https://www.srk.com.pl (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ministry of State Assets. Zasady Finansowania Likwidacji Zakładów Górniczych w Polsce. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Ministry of Funds and Regional Policy. Program Funduszu na Rzecz Sprawiedliwej Transformacji – Dokument Wdrożeniowy; Ministry of Funds and Regional Policy: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/strony/o-funduszach/programy-2021-2027/fundusz-na-rzecz-sprawiedliwej-transformacji/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Białecka, B.; Midor, K.; Zasadzień, M. Analiza Kierunków Zagospodarowania Terenów Pogórniczych-Studium Przypadku. [In:] Białek, J.; Mielimąka, R.; Czerwińska-Lubszczyk, A. Górnictwo Perspektywy, Zagrożenia. BHP Oraz Ochrona i Rekultywacja Powierzchni, Wydawnictwo P.A. Nova 2014. pp. 41–49. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/pl/sheet/214/fundusz-na-rzecz-sprawiedliwej-transformacji (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- World Bank. Managing Coal Mine Closure: Achieving a Just Transition for All; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/484541544643269894/pdf/130659-REVISED-PUBLIC-Managing-Coal-Mine-Closure-Achieving-a-Just-Transition-for-All-November-2018-final.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Śniegocki, A.; Wasilewski, M.; Zygmunt, I.; Look, W. Just Transition in Poland: A Review of Public Policies to Assist Polish Coal Communities in Transition; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA; WiseEuropa: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; Available online: https://www.rff.org/publications/reports/just-transition-in-poland-a-review-of-public-policies-to-assist-polish-coal-communities-in-transition/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- European Commission. A Just Transition Mechanism–Making Sure No One Is Left Behind. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_20_39 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- European Commission. Just Transition Fund (JTF). Implementation and Monitorin. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/funding/jtf/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; Kantor-Pietraga, I. Paths of Environmental and Economic Reclamation: The Case of Post-Mining Brownfields. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2012, 21, 219–223. Available online: http://www.pjoes.com/Paths-of-Environmental-and-Economic-r-nReclamation-the-Case-of-Post-Mining-Brownfields,88745,0,2.html (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Szady, E. Wykorzystanie terenów likwidowanych kopalń w opiniach górników. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śląskiej Ser. Archit. 1995, 25, 63–75. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/Content/15399 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Domański, B. Przekształcenia terenów poprzemysłowych w województwach śląskim i małopolskim–prawidłowości i uwarunkowania. Pr. Kom. Geogr. Przemysłu Pol. Tow. Geogr. 2001, 3, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszek, M. Sukcesja Funkcji Ekonomicznych na Terenach Pogórniczych na Przykładzie Województwa śląskiego. Ph.D. Thesis, Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny, Katowice, Poland, 2020. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Janikowska, O.; Kulczycka, J. Just Transition as a Tool for Preventing Energy Poverty among Women in Mining Areas—A Case Study of the Silesia Region, Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, W.H.; Herbst, D.B.; Hornberger, M.I.; Mebane, C.A.; Short, T.M. Long-Term Monitoring Reveals Convergent Patterns of Recovery from Mining Contamination across Four Western US Watersheds. Freshw. Sci. 2021, 40, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M.; Nowak, A. Planowanie przestrzenne a rewitalizacja obszarów zdegradowanych. Urbanistyka i Architektura 2021, 49, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Najwyższa Izba Kontroli. Kontrola Likwidacji Kopalni „Krupiński” (Nr ewid. 76/2023/D/22/508/KGP); NIK: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/aktualnosci/likwidacja-kopalni-krupinski.html (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Uberman, R.; Pietrzyk-Sokulska, E.; Kulczycka, J. Ocena wpływu działalności górniczej na środowisko–tendencje zmian. Przyszłość. Świat-Eur. 2014, 2, 87–119. [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk-Świątek, A. Architektura i Aktywny Przemysł Ciężki. O Przedsięwzięciach Wpływających na Społeczne Postrzeganie Przemysłu W świetle Niemieckich i Polskich Doświadczeń z Rewitalizacją Terenów Związanych z Górnictwem. Ph.D. Thesis, Politechnika Krakowska, Kraków, Poland, 2023. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Gasidło, K.; Wyrzykowska, A. Tereny pogórnicze w dokumentach strategicznych miast Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowskiej Metropolii. Builder 2022, 305, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowski, R.; Solarski, M.; Rzetala, M.A.; Rzetala, M.; Hamdaoui, A. The Impact of Hard Coal Mining on the Long-Term Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Land Subsidence in the Urban Area (Bielszowice, Poland). Resources 2024, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Wirth, P.; Lintz, G. Governing post-mining potentials: The role of regional capacities. In Post-Mining Regions in Central Europe: Problems, Potentials, Possibilities; Wirth, P., Cernic-Mali, B., Fischer, W., Eds.; oekom Verlag 2012; pp. 168–181. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter-Wirth-3/publication/343152248_Post-Mining_Regions_in_CenâĂę (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 roku. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ministry of Climate and Environment (Poland). Krajowy Plan na Rzecz Energii i Klimatu na Lata 2021–2030 (NECP). 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/krajowy-plan-na-rzecz-energii-i-klimatu (accessed on 27 March 2025).

| Level | Document | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Local | General Municipal Plan | Primary planning document at the local level; defines spatial policy and land use [63] |

| Local Spatial Development Plan (LSDP) | Legally binding local document detailing land use and building regulations; crucial for post-mining area revitalisation [64] | |

| Decision on Land Development Conditions | Issued when no local plan exists; applicable to changes in land use on post-mining sites [64] | |

| Integrated Investment Plan (IIP) | Enables complex investment projects in designated areas; essential for coordinated transformation efforts [60,61] | |

| Strategic Intervention Area (SIA) | Targets areas in need of special support, including post-mining regions; enables preferential access to national and EU funding [62,65] | |

| Municipal Development Strategy | Should align with regional policies and reflect local conditions and community needs [66] | |

| Regional | Regional Spatial Development Plan | Defines spatial policies at the voivodeship level; includes problematic areas requiring revitalisation [67] |

| Regional Development Strategy | Highlights the need for economic diversification and post-mining land revitalisation [57] | |

| Operational Plans at the Regional Level | Support just transition for coal regions, addressing socio-economic impacts of mine closures [68] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Structured and Legally Anchored Closure Process: | Lack of Strategic Integration: |

| The legal and procedural clarity of the mine closure phase, managed by the Mine Restructuring Company (SRK S.A.), ensures that environmental and safety standards are met uniformly across decommissioned sites. | The absence of a coordinated national or regional strategy for post-reclamation land use often leads to fragmented development and missed opportunities for holistic urban or regional regeneration. |

| Reuse of Existing Infrastructure: | Vulnerability to Land Neglect: |

| The capacity to repurpose industrial buildings and technical infrastructure facilitates resource efficiency, reducing the environmental footprint and financial burden of redevelopment. | Where planning is lacking, post-mining areas may fall into neglect, become underused, or even pose hazards. This not only delays potential revitalisation but also creates environmental and social risks. |

| Potential for Social Inclusion: | Planning Constraints: |

| Both planned and spontaneous reuse scenarios can support local engagement. In particular, unplanned recreational use of post-mining landscapes often fosters community interaction and promotes healthier lifestyles. | Rigid spatial planning categories, especially the persistent classification of sites as “industrial”, limit flexibility in reimagining these areas for new functions aligned with sustainable urban growth. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wyrzykowska, A.; Janiszek, M. Models of Post-Mining Land Reuse in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209069

Wyrzykowska A, Janiszek M. Models of Post-Mining Land Reuse in Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209069

Chicago/Turabian StyleWyrzykowska, Aleksandra, and Monika Janiszek. 2025. "Models of Post-Mining Land Reuse in Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209069

APA StyleWyrzykowska, A., & Janiszek, M. (2025). Models of Post-Mining Land Reuse in Poland. Sustainability, 17(20), 9069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209069