Non-Food Geographical Indications in the European Union: Comparative Indicators, Cluster Typologies, and Policy Scenarios Under Regulation (EU) 2023/2411

Abstract

1. Introduction

- to build an integrated dataset combining EUIPO data with Eurostat indicators (population and GDP), thereby offering a harmonised comparative picture;

- to apply normalised indicators (GI/population, GI/GDP) that highlight relative specialisations and enable fairer cross-country comparisons;

- to elaborate policy scenarios, translating EPRS estimates into concrete trajectories (business as usual, intermediate adoption, full implementation) and assessing their economic and territorial implications.

- RQ1: What is the geographical and sectoral distribution of non-food GIs in the EU, and how does it change when using comparative indicators?

- RQ2: Which implementation scenarios of Regulation (EU) 2023/2411 are plausible, and what economic and territorial effects can be expected?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. GIs, Territory, and Development

2.2. Regulatory Frameworks and Models

2.3. Governance of Non-Food GIs

2.4. Three Lenses: RBV, Institutions, and Place-Based Development

2.5. GIs and Sustainability Transitions

2.6. Implications for Comparative Measurement

2.7. Research Gaps and Contribution

2.8. Alignment with the Research Questions

- RQ1. What is the geographical and sectoral distribution of non-food GIs in the EU, and how does it change when using comparative indicators?

- RQ2. Which implementation scenarios of Regulation (EU) 2023/2411 are plausible, and what economic and territorial effects can be expected?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

- Collection and harmonisation of secondary institutional datasets (EUIPO, EPRS, Eurostat);

- Descriptive and comparative statistical analysis to capture geographical and sectoral patterns and relative intensity through normalised indicators (GI/POP, GI/GDP);

- Scenario analysis converting institutional estimates into plausible policy trajectories (business as usual, intermediate adoption, full implementation).

3.2. Secondary Data Analysis (SDA)

- (1)

- Source identification. Authoritative institutional datasets were selected to guarantee reliability and comparability, including EUIPO [55] for non-food GIs, the European Parliamentary Research Service [12] for Cost of Non-Europe benchmarks, and Eurostat for socio-economic indicators such as population and GDP.

- (2)

- Data extraction and harmonisation. All records were organised into a database covering product type, country of origin, and legal status (registered or potential). Classifications were aligned with EUIPO definitions, and categories such as ceramics, textiles, glass, and stone were standardised for cross-country consistency. To prevent duplication, potential entries were cross-checked against registered titles at the level of each country and product category.

- (3)

- Validation and quality control. Data were verified through double-entry checks and compared with national registries where available. The Eurostat Quality Assurance Framework (2023) was used as a benchmark to ensure coherence, comparability, and traceability of all data procedures [77].

3.3. Documentary Analysis

3.4. Descriptive and Comparative Statistics

- GI/POP = Number of GIs/Population (million)

- GI/GDP = Number of GIs/GDP (€ billion)

3.5. Policy Frameworks for Interpretation

3.6. Limitations

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Overview

4.2. Sectoral Distribution

4.3. Comparative Indicators

4.4. Country Clusters

4.5. Governance Patterns Across Clusters

4.6. Integration with Socio-Economic Indicators

4.7. Scenario Analysis

4.7.1. Scenarios and Assumptions

- Business as usual (BAU): limited adoption of Regulation (EU) 2023/2411, with about 0–10% of potential titles registered within five years. Effects on jobs and intra-EU trade remain marginal, and country rankings do not change.

- Intermediate adoption: partial implementation, with around 40–50% of potential titles registered, mostly in Member States that already have governance capacity (Emerging players). Estimated effects: +150,000–180,000 jobs and +€18–25 billion of intra-EU trade.

- Full implementation: widespread registration of 80–100% of potential GIs within five years, producing the highest territorial benefits and aligning with previous EPRS estimates (+284,000–338,000 jobs and +€37–50 billion of intra-EU trade).

4.7.2. Sensitivity and Robustness

4.7.3. Potential Bias and Risk of Overestimation

4.7.4. Distributional Effects by Cluster

5. Discussion

5.1. GIs as Drivers of Territorial Development

5.2. The Role of Institutions and Governance

5.3. Comparative Insights Beyond Europe

5.4. GIs and Sustainability Transitions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moschini, G.; Menapace, L.; Pick, D. Geographical Indications and the Competitive Provision of Quality in Agricultural Markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menapace, L.; Moschini, G. Quality Certification by Geographical Indications, Trademarks and Firm Reputation. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2012, 39, 539–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangnekar, D. Remaking Place: The Social Construction of a Geographical Indication for Feni. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 2043–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie-Vivien, D. Do Geographical Indications for Handicrafts Deserve a Special Regime? Insights from Worldwide Law and Practice. In The Importance of Place: Geographical Indications as a Tool for Local and Regional Development; Ius Gentium; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 58, pp. 221–252. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, B. ‘Designating’ the Future of Geographical Indications. J. Intellect. Prop. Law Pract. 2024, 19, 693–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembré, S. Rescuing the Craft: Lace Craft Schools in France and Belgium from the 1850s to the 1930s. Hist. De L’education 2009, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslin-Perrier, C. Development of Limoges Porcelain. Ind. Ceram. Verriere 2009, 42–83. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyńska, D.; Khachlouf, N. How Proximity Matters in Interactive Learning and Innovation: A Study of the Venetian Glass Industry. Ind. Innov. 2018, 25, 874–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalaglio, A.; Guerrieri, F.; Carls, S. Sui Generis Geographical Indications for the Protection of Non-Agricultural Products in the EU: Can the Quality Schemes Fulfil the Task? IIC Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2020, 51, 31–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UIBM Non Agricultural GI Protection. Available online: https://rapporti-uibm.mise.gov.it/index.php/eng/regulatory/non-agricultural-gi-protection (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- EPRS Geographical Indications for Non-Agricultural Products. Cost of Non-Europe Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/631764/EPRS_STU(2019)631764_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M.A. The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-based View. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-Based vs Place-Neutral Approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and Its Prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, V.; Falco, C.; Curzi, D.; Olper, A. Trade Effects of Geographical Indication Policy: The EU Case. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Giua, M.; Salvatici, L.; Vaquero-Piñeiro, C. The International Trade Impacts of Geographical Indications: Hype or Hope? Food Policy 2022, 112, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A. Origin Products, Geographical Indications and Rural Development. In Labels of Origin for Food: Local Development, Global Recognition; Barham, E., Sylvander, B., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vandecandelaere, E.; Samper, L.F.; Rey, A.; Daza, A.; Mejía, P.; Tartanac, F.; Vittori, M. The Geographical Indication Pathway to Sustainability: A Framework to the Contributions of Geographical Indications to Sustainability through a Participatory Process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeney, M. The Protection of Geographical Indications: Law and Practice, 3rd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; p. 670. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, M.C.; Guareschi, M.; Bellassen, V.; Arfini, F. Geographical Indications and Public Good Relationships: Evidence and Policy Implications. EuroChoices 2022, 21, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, I.; Martins, L. As Implicações Do Regulamento (EU) 2023/2411, Nos Direitos de Indicações Geográficas de Produtos Artesanais e Industriais Concedidos e Registados Em Portugal. Rev. Jurídica 2024, 4, 275. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A.; Touzard, J.-M. Geographical Indications, Public Goods, and Sustainable Development: The Roles of Actors’ Strategies and Public Policies. World Dev. 2017, 98, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecandelaere, E.; Samper, L.F.; Tartanac, F.; Vittori, M. Sustainability Strategy for GIs; A Bottom-Up and Participatory Approach for GI Sustainability. In Worldwide Perspectives on Geographical Indications: Crossed Views Between Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners; Vandecandelaere, E., Marie-Vivien, D., Thévenod-Mottet, E., Bouhaddane, M., Pieprzownik, V., Tartanac, F., Puzone, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 343–353. ISBN 978-3-031-71641-6. [Google Scholar]

- Segre, G.; Russo, A.P. Collective Property Rights for Glass Manufacturing in Murano: Where Culture Makes or Breaks Local Economic Development; University of Turin, EBLA Center (Dipartimento di Economia “S. Cognetti de Martiis”): Torino, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D’Avigneau, V.M.; Kiraly, T. The New Regulation (EU) 2023/2411 on the Protection of Geographical Indications for Craft and Industrial Products: An Additional Mean to Support Sustainability; Sciencesconf/FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, S. Embedding Local Places in Global Spaces: Geographical Indications as a Territorial Development Strategy. Rural Sociol. 2010, 75, 209–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalaglio, A.; Bonadio, E. The Future of Geographical Indications: European and Global Perspectives. In The Future of Geographical Indications: European and Global Perspectives; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 1–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huysmans, M.; van Noord, D.; Höhn, G.L. Do Geographical Indications Certify Origin and Quality? In Worldwide Perspectives on Geographical Indications: Crossed Views Between Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners; Vandecandelaere, E., Marie-Vivien, D., Thévenod-Mottet, E., Bouhaddane, M., Pieprzownik, V., Tartanac, F., Puzone, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-3-031-71641-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mandrinos, S.; Mahdi, N.M.N. Theoretical Interplay of Resource Dependence and Institutional Theory in Context Bound Organisations. J. Gen. Manag. 2015, 41, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, H.V.J. Europe’s GI Policy and New World Countries. J. World Trade 2023, 57, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebola, T. Branding as a Tool to Promote Geographical Indication Exports and Sustainable Development in Africa. In The Elgar Companion to Intellectual Property and the Sustainable Development Goals; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 499–521. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, A. Protection of Geographical Indication Products from Different States of India. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights 2020, 25, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.A. TRIPS Compatibility of Bangladeshi Legal Regime on Geographical Indications and Its Ramifications: A Comparative Review. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2018, 21, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Gu, X. Study on the Protection System and Economic Impact of GIs in China. In Worldwide Perspectives on Geographical Indications: Crossed Views Between Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners; Vandecandelaere, E., Marie-Vivien, D., Thévenod-Mottet, E., Bouhaddane, M., Pieprzownik, V., Tartanac, F., Puzone, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 129–144. ISBN 978-3-031-71641-6. [Google Scholar]

- Risang Ayu Palar, M. A Model of Geographical Indication’s Product Specification for ASEAN Countries. In Worldwide Perspectives on Geographical Indications: Crossed Views Between Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners; Vandecandelaere, E., Marie-Vivien, D., Thévenod-Mottet, E., Bouhaddane, M., Pieprzownik, V., Tartanac, F., Puzone, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 223–238. ISBN 978-3-031-71641-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda, O.S., Sr. The Prospects, Benefits and Challenges of Sui Generis Protection of Geographical Indications of South Africa. Foreign Trade Rev. 2016, 51, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneller, E. EU-Australia FTA: Challenges and Potential Points of Convergence for Negotiations in Geographical Indications. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2020, 23, 546–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbert, H.; Petit, M. Are Geographical Indications a Valid Property Right? Global Trends and Challenges. Dev. Policy Rev. 2009, 27, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Absolute Protection for Geographical Indications: Protectionism or Justified Rights? Queen Mary J. Intellect. Prop. 2018, 8, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basole, A. Authenticity, Innovation, and the Geographical Indication in an Artisanal Industry: The Case of the Banarasi Sari. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2015, 18, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaguti, J.M.A.; Avrichir, I. Factors That the Specialized Literature Identifies as Limiting the Development of GIs: An Analysis through the Lens of the Stakeholder Engagement Theory. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2024, 62, e277978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahur, M. An Old Issue of Protecting GIs for Culture: A New Insight from the Experience of India and Bangladesh. Commonw. Law Bull. 2017, 43, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubia, P. Geographical Indications of Traditional Handicrafts: A Cultural Element in a Predominantly Economic Activity. IIC Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2019, 50, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I.; Costa, P. Job Crafting after Making Mistakes: Can Leadership Be an Obstacle? Learn. Organ. 2023, 30, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Zhao, L. Understanding Purchase Intention of Fair Trade Handicrafts through the Lens of Geographical Indication and Fair Trade Knowledge in a Brand Equity Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cei, L. The Distribution of Geographical Indications across Europe. Reflecting Spatial Patterns and the Role of Policy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2025, 33, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumangane, M.B.G.; Granato, S.; Lapatinas, A.; Mazzarella, G. Causal Estimates of Geographical Indications’ Effects on Territorial Development: Feasibility and Application; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DeNicola, A.O. Asymmetrical Indications: Negotiating Creativity through Geographical Indications in North India. Econ. Anthropol. 2016, 3, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitelis, C.; Teece, D.J. Cross-border Market Co-creation, Dynamic Capabilities and the Entrepreneurial Theory of the Multinational Enterprise. Ind. Corp. Change 2010, 19, 1247–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUIPO. Study on EU Member States’ Potential for Protecting Craft and Industrial Geographical Indications 2024; EUIPO: Alicante, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Nigmann, T.; Schreiber, C.; Neilson, J. Collective Action Milieus and Governance Structures of Protected Geographical Indications for Coffee in Colombia, Thailand and Indonesia. Int. J. Commons 2020, 14, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialisation, Regional Growth and Applications to EU Cohesion Policy. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P. Place-Based Policies for the Future: How Have Place-Based Policies Evolved to Date and What Are They for Now? OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Foray, D. Smart Specialisation: Opportunities and Challenges for Regional Innovation Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional Competitiveness and Territorial Capital: A Conceptual Approach and Empirical Evidence from the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejević Panić, T.; Cvetanović, S. Territorial Capital and Regional Development Strategies: Evidence from Southeast Europe. Spatium 2025, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Micro-Foundations of the Multi-Level Perspective on Socio-Technical Transitions: Developing a Multi-Dimensional Model of Agency Through Crossovers Between Social Constructivism, Evolutionary Economics and Neo-Institutional Theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 152, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guareschi, M.; Mancini, M.C.; Arfini, F. Measuring the Contribution of Geographical Indications to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 103, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasco, S.; Caputo, P.; Garrone, P.; Randellini, N. Are Geographical Indication Products Environmentally Sound? The Case of Pears in North of Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 467, 142963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 (SOFI 2021); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barucco, M.A.; Cattaruzza, E.; Silverio, M. MURANO PIXEL. An Experimental and Shared Research; Barucco, M.A., Cattaruzza, E., Chiesa, R., Eds.; Anteferma Edizioni: Venice, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Epure, C.; Munteanu, C.; Istrate, B.; Harja, M.; Lupu, F.C.; Luca, D. Innovation in the Use of Recycled and Heat-Treated Glass in Various Applications: Mechanical and Chemical Properties. Coatings 2025, 15, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, V.; Curzi, D.; Arfini, F.; Falco, C. Dynamic and spatial approaches to assess the impact of geographical indications on rural areas. J. Rural. Studies 2024, 108, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Penker, M.; Vogl, C.R.; Samper-Gartner, L.F. Can Origin Labels Re-Shape Relationships along International Supply Chains?—A Case Study of the Coffee Sector in Colombia. Int. J. Commons 2016, 10, 230–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5264-4565-0. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5063-3616-9. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, M.; Daim, T.U.; Jetter, A. A Review of Scenario Planning. Futures 2013, 46, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Improving Governance with Policy Evaluation: Lessons from Country Experiences; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.P. Secondary Data Analysis: A Method of Which the Time Has Come. Qual. Quant. Methods Libr. 2014, 3, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian, T.P. Secondary Data Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Statistical System Committee (ESSC). Eurostat. ESS Quality Assurance Framework (ESS-QAF) Version 2.0; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Regulation (EU). 2023/2411 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 on Geographical Indication Protection for Craft and Industrial Products; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Shook, C.L. The Application of Cluster Analysis in Strategic Management Research: An Analysis and Critique. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuferová, E.; Čabinová, V.; Matijová, M. Categorization of the EU Member States in the Context of Selected Multicriteria International Indices Using Cluster Analysis. Rev. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 20, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0-471-87876-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.C.; Staus, A. European Food Quality Policy: The Importance of Geographical Indications, Organic Certification and Food Quality Insurance Schemes in European Countries; European Association of Agricultural Economists (EAAE): Ghent, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, T.C. European Food Quality Policy: The Importance of Geographical Indications, Organic Certification and Food Quality Assurance Schemes in European Countries. Estey Cent. J. Int. Law Trade Policy 2009, 10, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Better Regulation Toolbox (2021 Edition); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, G. Structural Policy and Multilevel Governance in the EC. In The State of the European Community, Volume 2: The Maastricht Debates and Beyond; Cafruny, A., Rosenthal, G., Eds.; Longman: Harlow, UK, 1993; pp. 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Multi-Level Governance and European Integration; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2001; ISBN 9780742510193. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780761914176. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M.; Semieniuk, G. Financing Renewable Energy: Who Is Financing What and Why It Matters. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 127, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Better Regulation Toolbox—Chapter 8: Methodologies for Analysing Impacts in IAs, Evaluations and Fitness Checks; European Commission Secretariat-General: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, A.E.; Greenberg, D.H.; Vining, A.R.; Weimer, D.L. Cost–Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tregear, A.; Arfini, F.; Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A. Regional Foods and Rural Development: The Role of Product Qualification. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, B. Empirical Investigation of Fraud and Unfair Competition Practices in France and Vietnam: Actors, Types and Drivers. In Worldwide Perspectives on Geographical Indications: Crossed Views Between Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners; Vandecandelaere, E., Marie-Vivien, D., Thévenod-Mottet, E., Bouhaddane, M., Pieprzownik, V., Tartanac, F., Puzone, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 201–221. ISBN 978-3-031-71641-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sautier, D.; Biénabe, E.; Cerdan, C. Geographical Indications in Developing Countries: A Tool for Sustainable Development? J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 1527–1546. [Google Scholar]

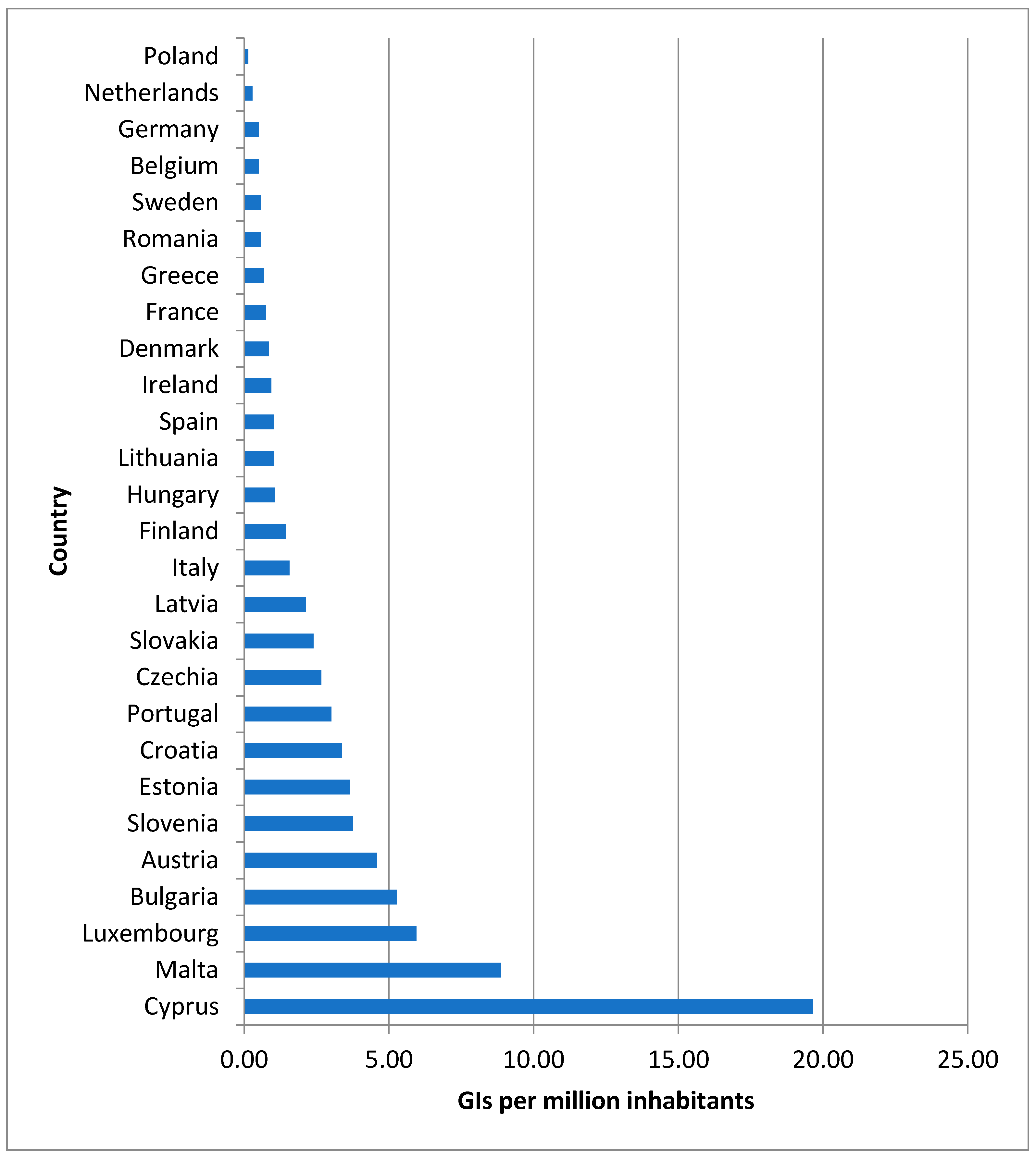

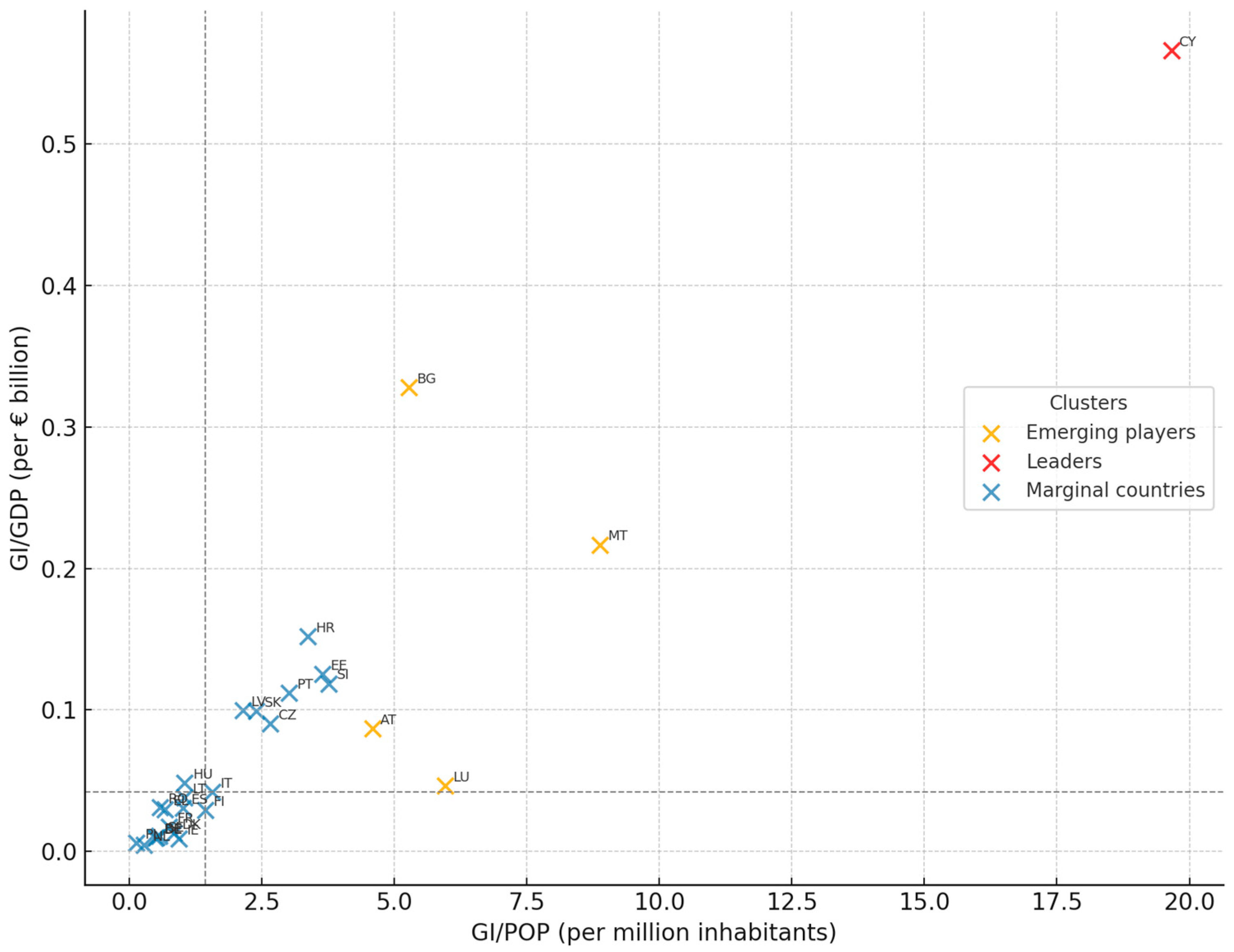

| Country | Registered | Potential | Total | GIs per Million Inhabitants | GIs per € Billion GDP | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyprus | 0 | 19 | 19 | 19.66 | 0.57 | Leaders |

| Austria | 0 | 42 | 42 | 4.59 | 0.09 | Emerging players |

| Portugal | 26 | 6 | 32 | 3.01 | 0.11 | Emerging players |

| Czechia | 25 | 4 | 29 | 2.66 | 0.09 | Emerging players |

| Italy | 0 | 92 | 92 | 1.56 | 0.04 | Emerging players |

| Spain | 0 | 49 | 49 | 1.01 | 0.03 | Emerging players |

| France | 22 | 29 | 51 | 0.74 | 0.02 | Emerging players |

| Germany | 2 | 39 | 41 | 0.49 | 0.01 | Emerging players |

| Malta | 0 | 5 | 5 | 8.87 | 0.22 | Marginal countries |

| Luxembourg | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5.95 | 0.05 | Marginal countries |

| Bulgaria | 27 | 7 | 34 | 5.28 | 0.33 | Marginal countries |

| Slovenia | 2 | 6 | 8 | 3.77 | 0.12 | Marginal countries |

| Estonia | 0 | 5 | 5 | 3.64 | 0.13 | Marginal countries |

| Croatia | 4 | 9 | 13 | 3.37 | 0.15 | Marginal countries |

| Slovakia | 12 | 1 | 13 | 2.4 | 0.1 | Marginal countries |

| Latvia | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2.14 | 0.1 | Marginal countries |

| Finland | 0 | 8 | 8 | 1.43 | 0.03 | Marginal countries |

| Hungary | 9 | 1 | 10 | 1.04 | 0.05 | Marginal countries |

| Lithuania | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1.04 | 0.04 | Marginal countries |

| Ireland | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.93 | 0.01 | Marginal countries |

| Denmark | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.84 | 0.01 | Marginal countries |

| Greece | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0.67 | 0,03 | Marginal countries |

| Romania | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0.58 | 0.03 | Marginal countries |

| Sweden | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0.57 | 0.01 | Marginal countries |

| Belgium | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0.51 | 0.01 | Marginal countries |

| Netherlands | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.28 | 0 | Marginal countries |

| Poland | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.01 | Marginal countries |

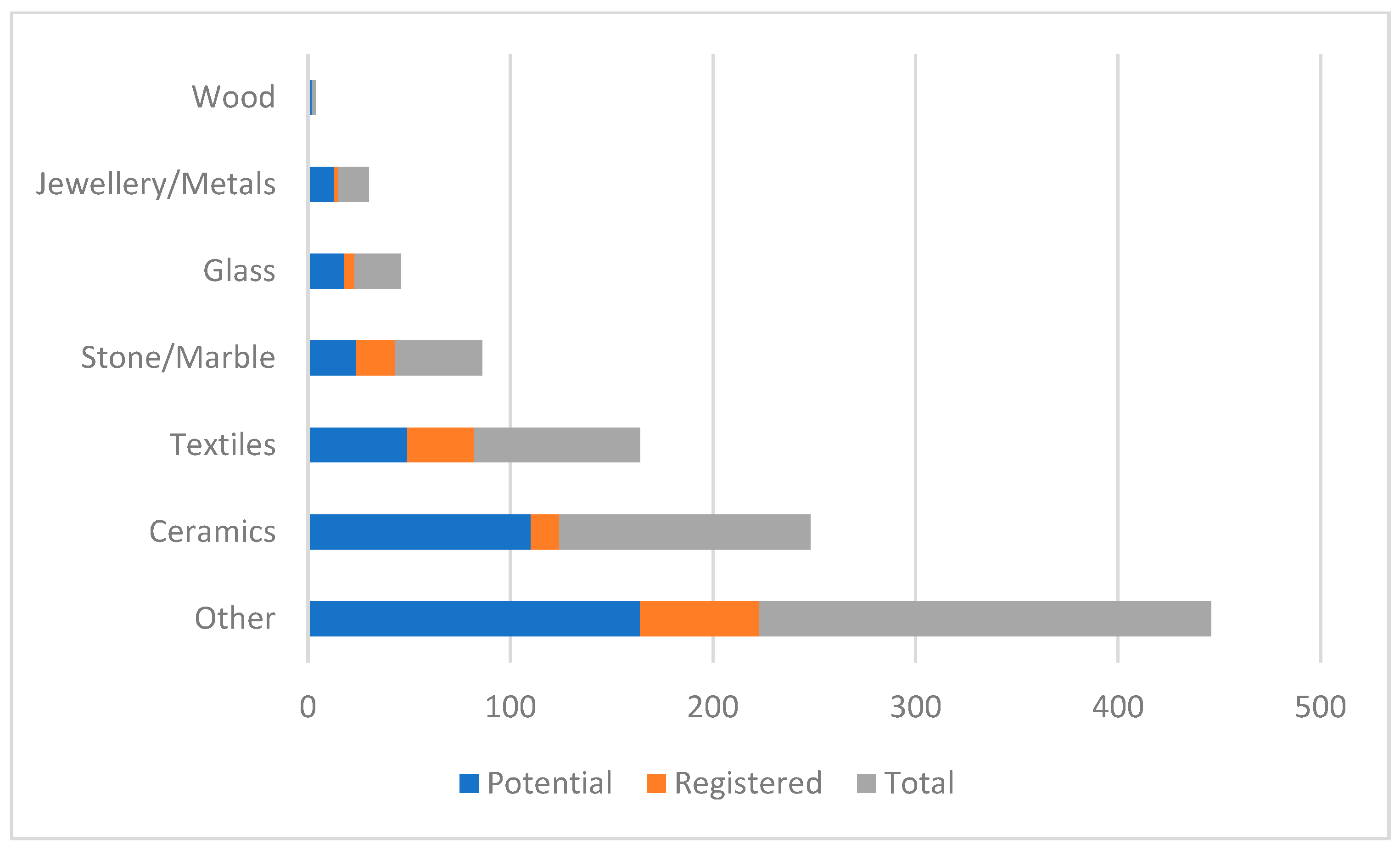

| Sector | Potential | Registered | Total | %_Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other | 164 | 59 | 223 | 43.6 |

| Ceramics | 110 | 14 | 124 | 24.2 |

| Textiles | 49 | 33 | 82 | 16 |

| Stone/Marble | 24 | 19 | 43 | 8.4 |

| Glass | 18 | 5 | 23 | 45 |

| Jewellery/Metals | 13 | 2 | 15 | 2.9 |

| Wood | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Scenario | % of Potential GIs Registered | Jobs (Estimate) | Intra-EU Trade (bn €) | Impact on Relative Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business as usual | ~0% | marginal | marginal | No change |

| Intermediate adoption | 40–50% | +150k–180k | +18–25 | Growth of emerging players |

| Full implementation | 100% | +284k–338k | +37–50 | New relative leaders |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peira, G.; Arnoldi, S.; Bonadonna, A. Non-Food Geographical Indications in the European Union: Comparative Indicators, Cluster Typologies, and Policy Scenarios Under Regulation (EU) 2023/2411. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209055

Peira G, Arnoldi S, Bonadonna A. Non-Food Geographical Indications in the European Union: Comparative Indicators, Cluster Typologies, and Policy Scenarios Under Regulation (EU) 2023/2411. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209055

Chicago/Turabian StylePeira, Giovanni, Sergio Arnoldi, and Alessandro Bonadonna. 2025. "Non-Food Geographical Indications in the European Union: Comparative Indicators, Cluster Typologies, and Policy Scenarios Under Regulation (EU) 2023/2411" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209055

APA StylePeira, G., Arnoldi, S., & Bonadonna, A. (2025). Non-Food Geographical Indications in the European Union: Comparative Indicators, Cluster Typologies, and Policy Scenarios Under Regulation (EU) 2023/2411. Sustainability, 17(20), 9055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209055