From Static Congruence to Dynamic Alignment: Person–Organization Fit Practices and Their Contribution to Sustainable HRM in Poland

Abstract

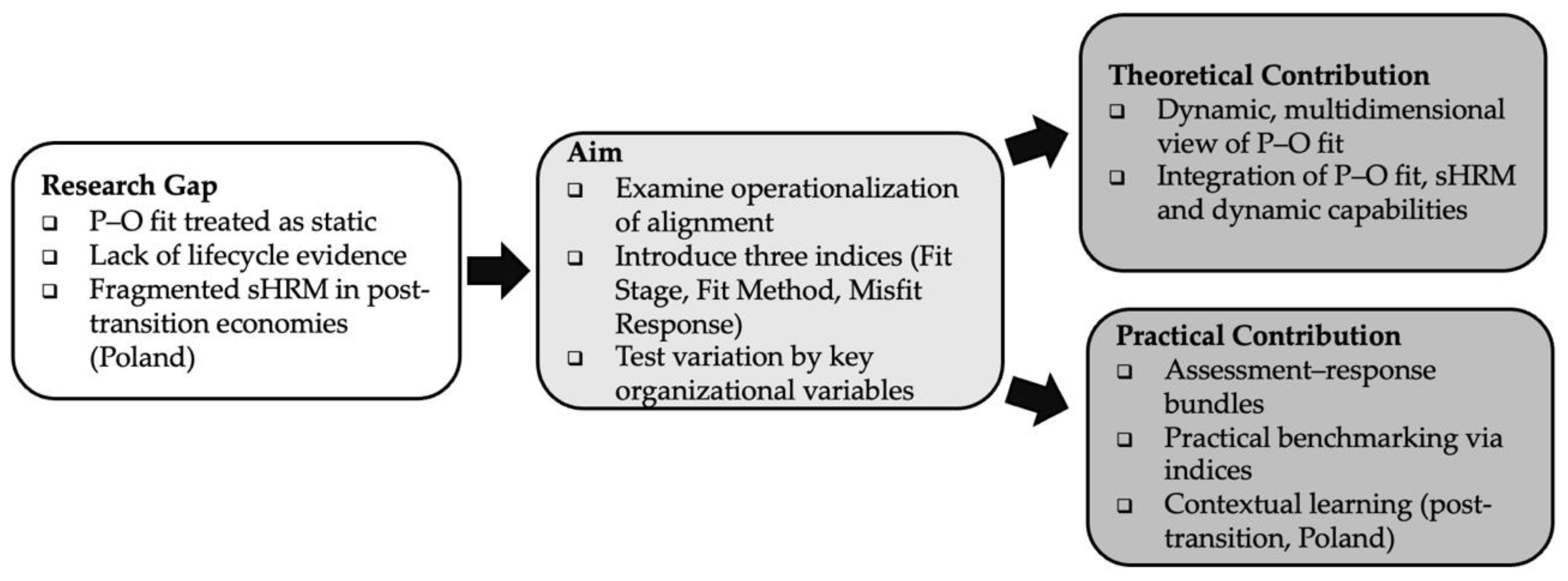

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Values and Value Alignment

2.2. Person–Organization Fit: Static and Dynamic Perspectives

2.3. Value Alignment Within Sustainable HRM

2.4. Dynamic Capabilities and Bundled Practices

2.5. Research Questions and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

- Fit Stage Score identifies where in the employee lifecycle organizations assess alignment, moving beyond the traditional focus on recruitment.

- Fit Method Score captures how alignment is evaluated, providing a measure of methodological diversity and formality.

- Misfit Response Score addresses what happens when misfit is detected, offering insight into whether organizations adopt structured remedial practices or ignore such challenges.

3.2. Sample

3.3. Measures

- Fit Stage Score (0–4): Measures the number of employment lifecycle stages at which alignment is assessed (CV screening, job interview, probation, permanent employment). This operationalization reflects the processual perspective on P–O fit, emphasizing that alignment is not limited to entry but may be revisited at later stages [4,6,7]. The selection of these four stages is consistent with the employee lifecycle perspective frequently applied in HRM research [43,44], yet the index itself represents an original operationalization developed for this study. As such, it provides an exploratory but systematic way to capture alignment across multiple phases of the employment relationship (see Supplementary Table S1).

- Fit Method Score (0–7): Captures the range of diagnostic tools used to evaluate alignment (structured interviews, psychometric tests, surveys, observation, supervisor consultation, and external consultancy or audit). The inclusion of diverse methods reflects both the static and dynamic perspectives in fit research, where different instruments can capture congruence at multiple points in time [22] (see Supplementary Table S2).

- Misfit Response Score (0–4): Records the extent of formalized organizational actions taken when misfit is identified (training, coaching or mentoring, job rotation or internal mobility, termination or exit procedures). Only structured, institutionally embedded practices were included, while informal or ad hoc interactions (e.g., one-off conversations or feedback) were excluded to ensure that the index captures systemic HRM responses rather than individual managerial discretion (see Supplementary Table S3).

3.4. Analytical Strategy

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Screening Questions

4.1.2. Descriptive Statistics of Alignment Indices

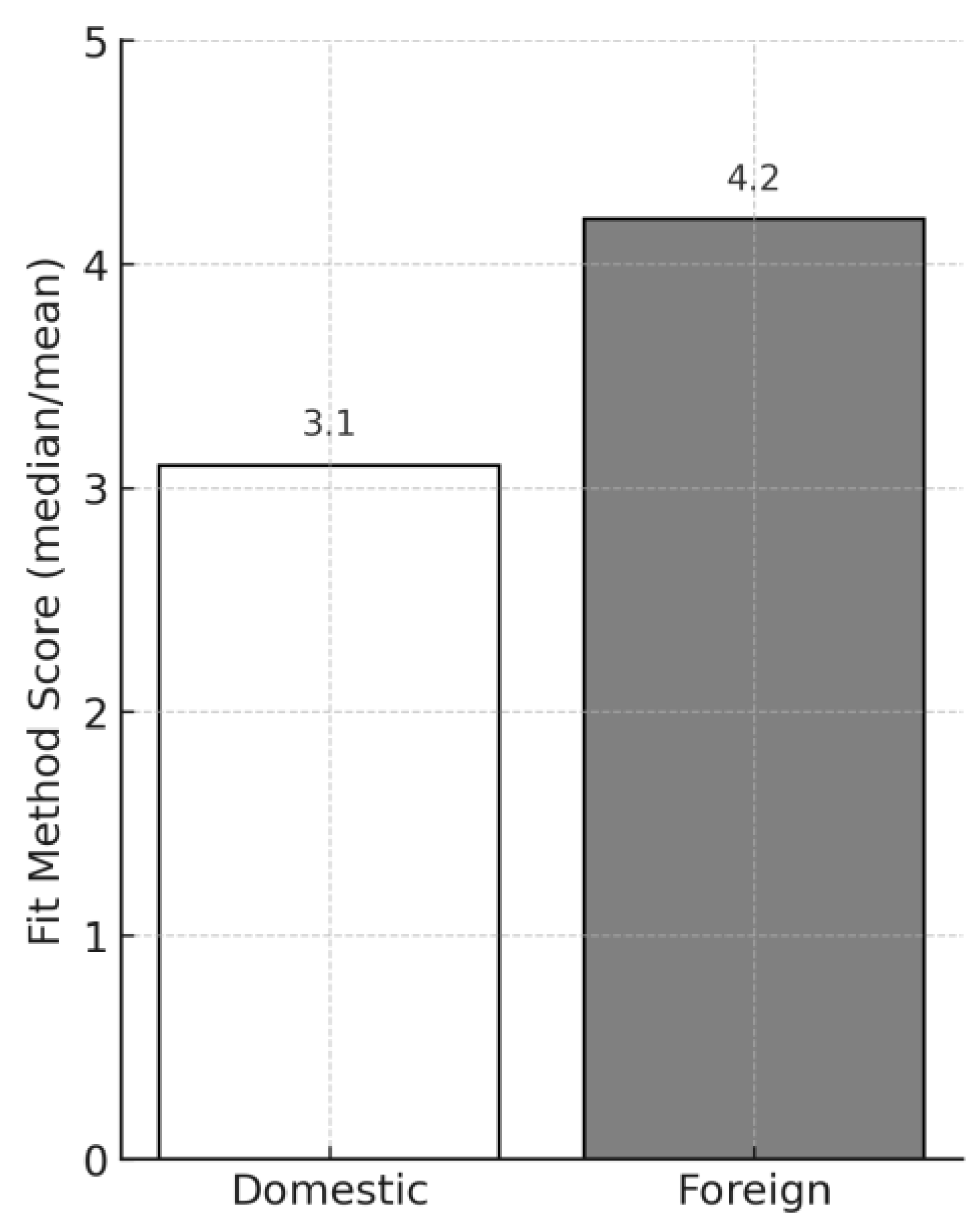

4.2. Ownership and the Scope of Fit Practices (H1)

4.3. Executive Gender and Fit Practices (H2)

4.4. Ownership Form (H3)

4.5. Sectoral Differences in Fit Practices (H4)

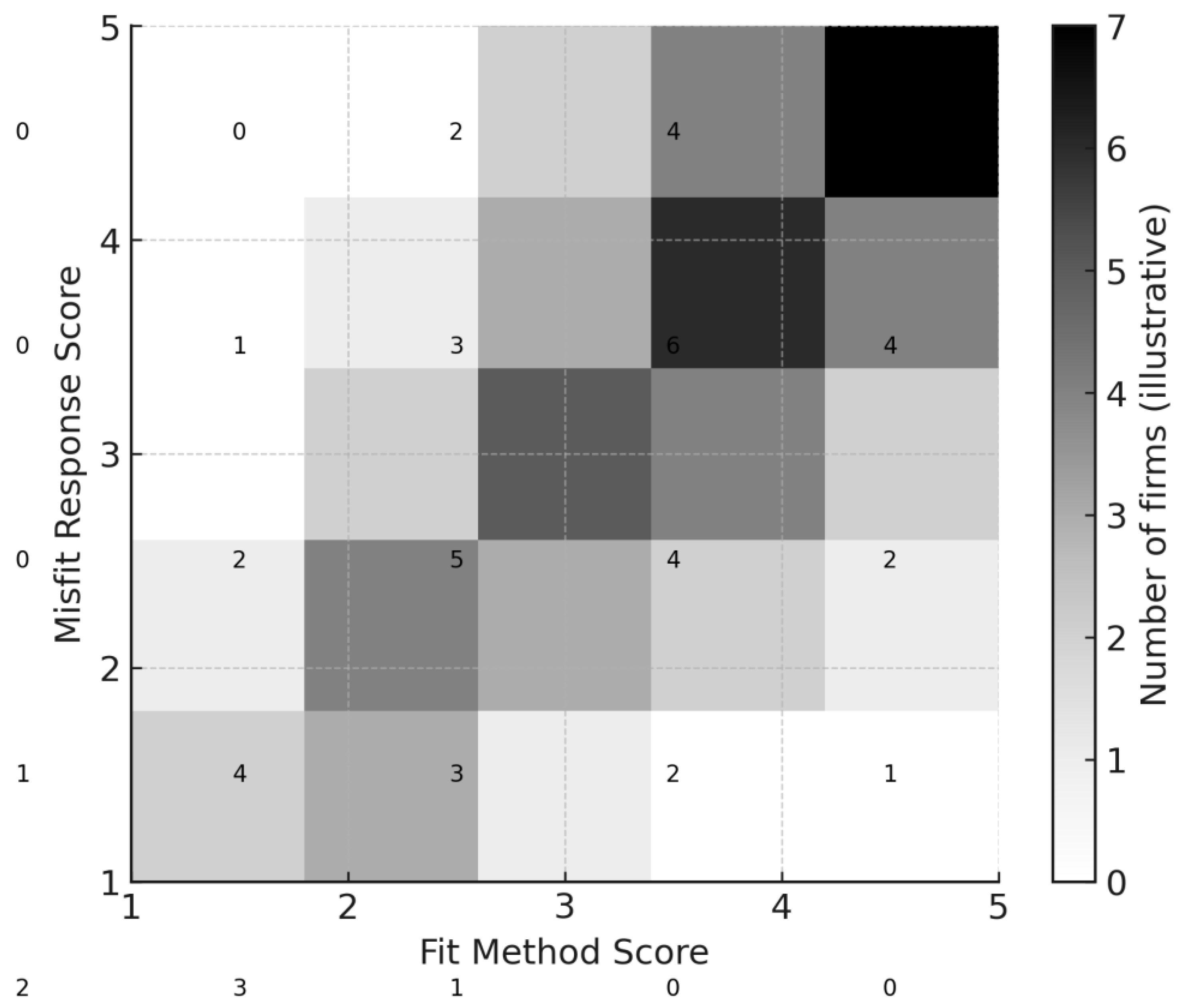

4.6. Fit Assessment and Misfit Response Strategies (H5)

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings and Interpretation

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

- Expand diagnostic practices. The foundation of alignment is systematic diagnosis. Organizations should extend assessment across multiple stages of the employee lifecycle (recruitment, probation, development, promotion, and exit) and diversify methods (structured interviews, validated psychometric tools, surveys, 360-degree feedback, audits). Diagnostics should be repeatable and comparable over time, allowing benchmarking and continuous improvement.

- Integrate diagnostics with responses. Assessments must always be connected to corrective measures. Effective bundles include mentoring, coaching, targeted training, job rotation, or structured exit when misfit persists. Diagnostics without follow-up risk becoming symbolic and eroding trust.

- Address sectoral logics. Process-oriented sectors (manufacturing, logistics, construction) already apply multiple checkpoints, but remedial actions remain underdeveloped. These industries should strengthen mentoring, training, and internal mobility. In service-oriented sectors (IT, retail, professional services), remedial actions are more common, but diagnostics remain narrow; extending assessments beyond early entry stages is the priority here.

- Strengthen public-sector practices. Even if statistical results showed no clear divergence, institutional legacies of bureaucracy and hierarchical governance continue to hinder alignment in public organizations. Introducing systematic assessment–response bundles would modernize HR systems and rebuild legitimacy.

- Embed alignment as a sustainable HRM capability. Corrective strategies allow employees to cope with misfit without immediate exit, reducing stress and increasing perceptions of fairness. By embedding assessment–response bundles into HRM systems, organizations can enhance both resilience and employee well-being.

5.4. Limitations

5.5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatman, J.A. Improving Interactional Organizational Research: A Model of Person-Organization Fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization Fit: An Integrative Review of Its Conceptualizations, Measurement, and Implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The people make the place. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Biron, M. Temporal Issues in Person–Organization Fit, Person–Job Fit and Turnover: The Role of Leader–Member Exchange. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 2177–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Person–Organization Fit, Job Choice Decisions, and Organizational Entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M. The Value of Value Congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.; Schneider, B.; Su, R. Person-organization Fit Theory and Research: Conundrums, Conclusions, and Calls to Action. Pers. Psychol. 2023, 76, 375–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond Strategic Human Resource Management: Is Sustainable Human Resource Management the next Approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management; Contributions to Management Science; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-7908-2187-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Dyrka, S.; Kokiel, A.; Urbańczyk, E. Sustainable HR and Employee Psychological Well-Being in Shaping the Performance of a Business. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B. Exploring Sustainable HRM Through the Lens of Employee Wellbeing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, P.; Czerw, A.; Ostafińska-Molik, B.; Chudzicka-Czupała, A. Flourishing at Work: Psychometric Properties of the Polish Version of the Workplace PERMA-Profiler. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being, 1st Free Press hardcover ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4391-9076-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bombiak, E. Advances in the Implementation of the Model of Sustainable Human Resource Management: Polish Companies’ Experiences. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 1667–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Mroziewski, R. Management by Values: A Case Study of a Recruitment Company. Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2020, 19, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poór, J.; Kazlakauiste, R.; Karoliny, Z.; Alas, R.; Kohont, A.; Slavic, A.; Kazlakauiste, R.; Buciunine, I.; Poór, J.; Karoliny, Z.S.; et al. Human Resource Management in the Central and Eastern European Region. In Global Trends in Human Resource Management; Parry, E., Stavrou, E., Lazarova, M., Eds.; Palgrave-Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 103–121. ISBN 978-0-23-35483-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. ISBN 978-0-12-015225-4. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, M.; Schwartz, S.H.; Surkiss, S. Basic Individual Values, Work Values, and the Meaning of Work. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 48, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-1-900961-27-1. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Penela, A.; Ruzo-Sanmartín, E.; García-Chas, R.; Troilo, F. Does Sustainable Recruitment Enhance Motivation? A Cross-country Analysis on the Role of Person-organization Fit. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 6983–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Billsberry, J.; Barrett, M. A Bibliometric Analysis of Person-Organization Fit Research: Significant Features and Contemporary Trends. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 73, 1971–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wu, D.; Xin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H. Formal Mentoring Support, Person–Environment Fit and Newcomer’s Intention to leave: Does Newcomer’s Uncertainty Avoidance Orientation Matter? Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1749–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Bodner, T.; Erdogan, B.; Truxillo, D.M.; Tucker, J.S. Newcomer Adjustment during Organizational Socialization: A Meta-Analytic Review of Antecedents, Outcomes, and Methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, D.E. Human Resource Management and Performance: Still Searching for Some Answers: Human Resource Management and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2011, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.M.; Yang, M.M.; Wang, Y. Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices, Employee Resilience, and Employee Outcomes: Toward Common Good Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Pekkarinen, A. Practices of Sustainable Human Resource Management in Three Finnish Companies: Comparative Case Study. South Asian J. Bus. Manag. Cases 2023, 12, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cruz, J.; Rincon-Roldan, F.; Pasamar, S. When the Stars Align: The Effect of Institutional Pressures on Sustainable Human Resource Management through Organizational Engagement. Eur. Manag. J. 2025, 43, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A. Sustainable HRM: Enhancing Organizational Resilience and Adaptability. Int. J. Sustain. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B. High Performance Work Systems and Firm Performance: A Synthesis of Research and Managerial Implications. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1998; Volume 16, pp. 53–101. [Google Scholar]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macduffie, J.P. Human Resource Bundles and Manufacturing Performance: Organizational Logic and Flexible Production Systems in the World Auto Industry. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1995, 48, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hu, J.; Baer, J.C. How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.-L.; Boxall, P. Instrumental Work Values and Responses to HR Practices: A Study of Job Satisfaction in a Chinese Manufacturer. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučiūnienė, I. The Transformation of Economies and Societies in Central and Eastern Europe—How Has It Contributed to Management and Organisation Science? J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2018, 23, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, A.; Van Woerkom, M.; Geuskens, G.; Blonk, R. A Classification of Human Resource Management Bundles for the Inclusion of Vulnerable Workers. Work 2024, 79, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S. Can Strategic HRM Bundles Decrease Emotional Exhaustion and Increase Service Recovery Performance? Int. J. Manpow. 2023, 44, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T. Transnational Transfer of Strategic Organizational Practices: A Contextual Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezsö, C.L.; Ross, D.G. Does Female Representation in Top Management Improve Firm Performance? A Panel Data Investigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Byron, K. Women on Boards and Firm Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1546–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, M.; Manfreda, K.L.; Vehovar, V. Web Survey Methodology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-85702-861-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K.; Park, J. The Life Cycle of Employee Engagement Theory in HRD Research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2019, 21, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyński, A.; Kołoszycz, E.; Karolewska-Szparaga, M. Cykl Życia Pracownika w Organizacji z Uwzględnieniem Koncepcji Doświadczenia Pracownika i Zaangażowania. Kwart. Nauk O Przedsiębiorstwie 2024, 68, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether One of Two Random Variables Is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. On the Interpretation of χ 2 from Contingency Tables, and the Calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1922, 85, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Roth, K. Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: Institutional and relational effects. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner, A.; Quintanilla, J.; Varul, M.Z. Country-of-Origin Effects, Host-Country Effects, and the Management of HR in Multinationals: German Companies in Britain and Spain. J. World Bus. 2001, 36, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, A. Foreign Subsidiary Perspectives on the Mechanisms of Global HRM Integration. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2008, 18, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner, A.; Edwards, T.; Tempel, A. Power, Institutions and the Cross-National Transfer of Employment Practices in Multinationals. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębkowska, K.; Kłosiewicz-Górecka, U.; Szymańska, A.; Wejt-Knyżewska, A.; Szymańska-Zybertowicz, K. Biznes na Wysokich Obcasach; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; ISBN 978-83-67575-77-5. [Google Scholar]

- Terjesen, S.; Couto, E.B.; Francisco, P.M. Does the Presence of Independent and Female Directors Impact Firm Performance? A Multi-Country Study of Board Diversity. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, J.; Schreyögg, G.; Koch, J. Organizational path dependence: Opening the black box. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.; Konlechner, S.; Güttel, W.H.; Reischauer, G. Overcoming Path-Dependent Dynamic Capabilities. Strateg. Organ. 2025, 23, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Schroeder, R.G. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Operational Performance: Recognizing Country and Industry Differences. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K. The Importance of Sectoral Differences in the Application of Complementary HRM Practices for Innovation Performance. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2002, 9, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.K.; Guthrie, J.P.; Wright, P.M. Human Resource Management and Labor Productivity: Does Industry Matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M. A Meta-analytic Investigation of the Relationship between HRM Bundles and Firm Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooderham, P.; Parry, E.; Ringdal, K. The Impact of Bundles of Strategic Human Resource Management Practices on the Performance of European Firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2041–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, S.A. High Performance Work Systems and Intermediate Indicators of Firm Performance Within the US Small Business Sector. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Right Management. The 2025 State of Careers Report 1: The Career Equation; Right Management, Talent Solutions, ManpowerGroup: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Randstad. Workmonitor 2025: Nowy Standard Miejsca Pracy; Randstad Polska Sp. z o.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Foreign-owned subsidiaries | 34 | 32.7 |

| Domestic-owned | 70 | 67.3 | |

| Form of ownership | Private | 35 | 33.7 |

| Public | 10 | 9.6 | |

| Other (cooperative, mixed ownership, NGO) | 59 | 56.7 | |

| Executive gender | Male | 30 | 28.8 |

| Female | 74 | 71.2 | |

| Sector | Trade | 22 | 21.2 |

| Manufacturing/Logistics/Construction | 24 | 23.1 | |

| IT & Professional Services (incl. Finance) | 28 | 26.9 | |

| Education/Health/Public | 17 | 16.3 | |

| Other (incl. agriculture) | 13 | 12.5 |

| Research Question (RQ) | Hypothesis (H) | Concept (Independent Variable) | Construct (Dependent Variable) | Statistical Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1: Do ownership patterns matter for fit practices? | H1a | Ownership (foreign vs. domestic) | Fit Stage Score | Mann–Whitney U |

| H1b | Ownership (foreign vs. domestic) | Fit Method Score | Mann–Whitney U | |

| H1c | Ownership (foreign vs. domestic) | Misfit Response Score | Mann–Whitney U | |

| RQ2: Does executive gender influence fit practices? | H2a | Executive gender (male vs. female) | Fit Stage Score | Mann–Whitney U |

| H2b | Executive gender (male vs. female) | Fit Method Score | Mann–Whitney U | |

| H2c | Executive gender (male vs. female) | Misfit Response Score | Mann–Whitney U | |

| RQ3: Does ownership form influence fit practices? | H3a | Form of ownership (private vs. public) | Fit Stage Score | Mann–Whitney U |

| H3b | Form of ownership (private vs. public) | Fit Method Score | Mann–Whitney U | |

| H3c | Form of ownership (private vs. public) | Misfit Response Score | Mann–Whitney U | |

| RQ4: Do sectors differ in fit practices? | H4a | Sector (5 categories) | Fit Stage Score | Kruskal–Wallis H |

| H4b | Sector (5 categories) | Fit Method Score | Kruskal–Wallis H | |

| H4c | Sector (5 categories) | Misfit Response Score | Kruskal–Wallis H | |

| RQ5: Are fit assessments linked with misfit responses? | H5a | Fit assessment (yes/no) | Misfit Response (any vs. none) | Fisher’s exact test |

| H5b | Fit Method (intensity) | Misfit Response (intensity) | Spearman’s rank correlation |

| Index | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Stage Score | 104 | 1.62 | 0.92 | 1 | 4 | 1.44 | 1.79 |

| Fit Method Score | 104 | 1.97 | 1.09 | 1 | 6 | 1.76 | 2.18 |

| Misfit Response Score | 104 | 1.21 | 0.50 | 1 | 3 | 1.12 | 1.31 |

| Hypothesis | Construct (Dependent Variable) | Median (Foreign) | Median (Domestic) | U Statistic/p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Fit Stage Score (0–4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1379.0/0.151 |

| H1b | Fit Method Score (0–7) | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1463.0/0.048 |

| H1c | Misfit Response Score (0–4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1409.5/0.099 |

| Hypothesis | Construct (Dependent Variable) | Median (Female) | Median (Male) | U Statistic/p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2a | Fit Stage Score (0–4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1115.0/0.972 |

| H2b | Fit Method Score (0–7) | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1023.5/0.519 |

| H2c | Misfit Response Score (0–4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1042.0/0.598 |

| Hypothesis | Construct (Dependent Variable) | Median (Private) | Median (Public) | U Statistic/p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3a | Fit Stage Score (0–4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 150.0/0.454 |

| H3b | Fit Method Score (0–7) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 168.0/0.851 |

| H3c | Misfit Response Score (0–4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 157.0/0.605 |

| Hypothesis | Construct (Dependent Variable) | Test Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H4a | Fit Stage Score (0–4) | 10.344 | 0.035 |

| H4b | Fit Method Score (0–7) | 2.863 | 0.582 |

| H4c | Misfit Response Score (0–4) | 2.906 | 0.574 |

| Hypothesis | Groups Compared | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| H5a | Assessment vs. Response | p < 0.001 |

| Hypothesis | Variables Compared | ρ/p-Value | Tercile Medians (Low/Medium/High) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5b | Fit Method Score vs. Misfit Response | 0.57/p < 0.001 | 1.0/2.0/2.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paleń-Tondel, P. From Static Congruence to Dynamic Alignment: Person–Organization Fit Practices and Their Contribution to Sustainable HRM in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209035

Paleń-Tondel P. From Static Congruence to Dynamic Alignment: Person–Organization Fit Practices and Their Contribution to Sustainable HRM in Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209035

Chicago/Turabian StylePaleń-Tondel, Patrycja. 2025. "From Static Congruence to Dynamic Alignment: Person–Organization Fit Practices and Their Contribution to Sustainable HRM in Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209035

APA StylePaleń-Tondel, P. (2025). From Static Congruence to Dynamic Alignment: Person–Organization Fit Practices and Their Contribution to Sustainable HRM in Poland. Sustainability, 17(20), 9035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209035