1. Introduction

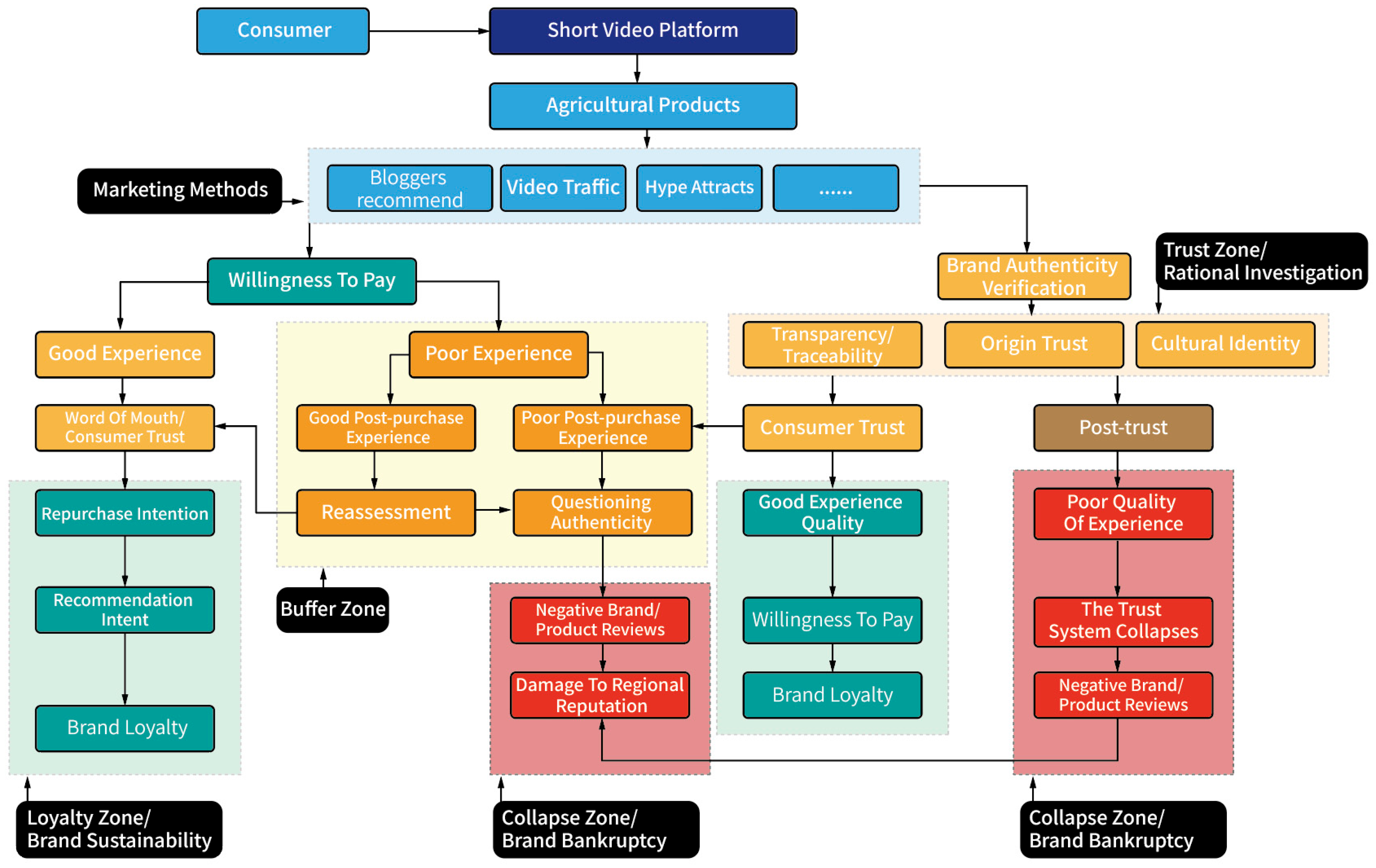

In China’s agricultural market, brand development has undergone cyclical phases of “sloganization—over-marketing—trust erosion [

1].” Although policies have consistently promoted agricultural branding, and academic research has confirmed the positive correlation between branding, price premiums, and farmers’ income, many “internet-famous landmarks” have experienced rapid decline. The root cause lies in insufficient supply capacity and experiential gaps, which ultimately erode consumer trust. Accordingly, brands should be understood not merely as marketing tools but as governance mechanisms grounded in information credibility and experiential consistency.

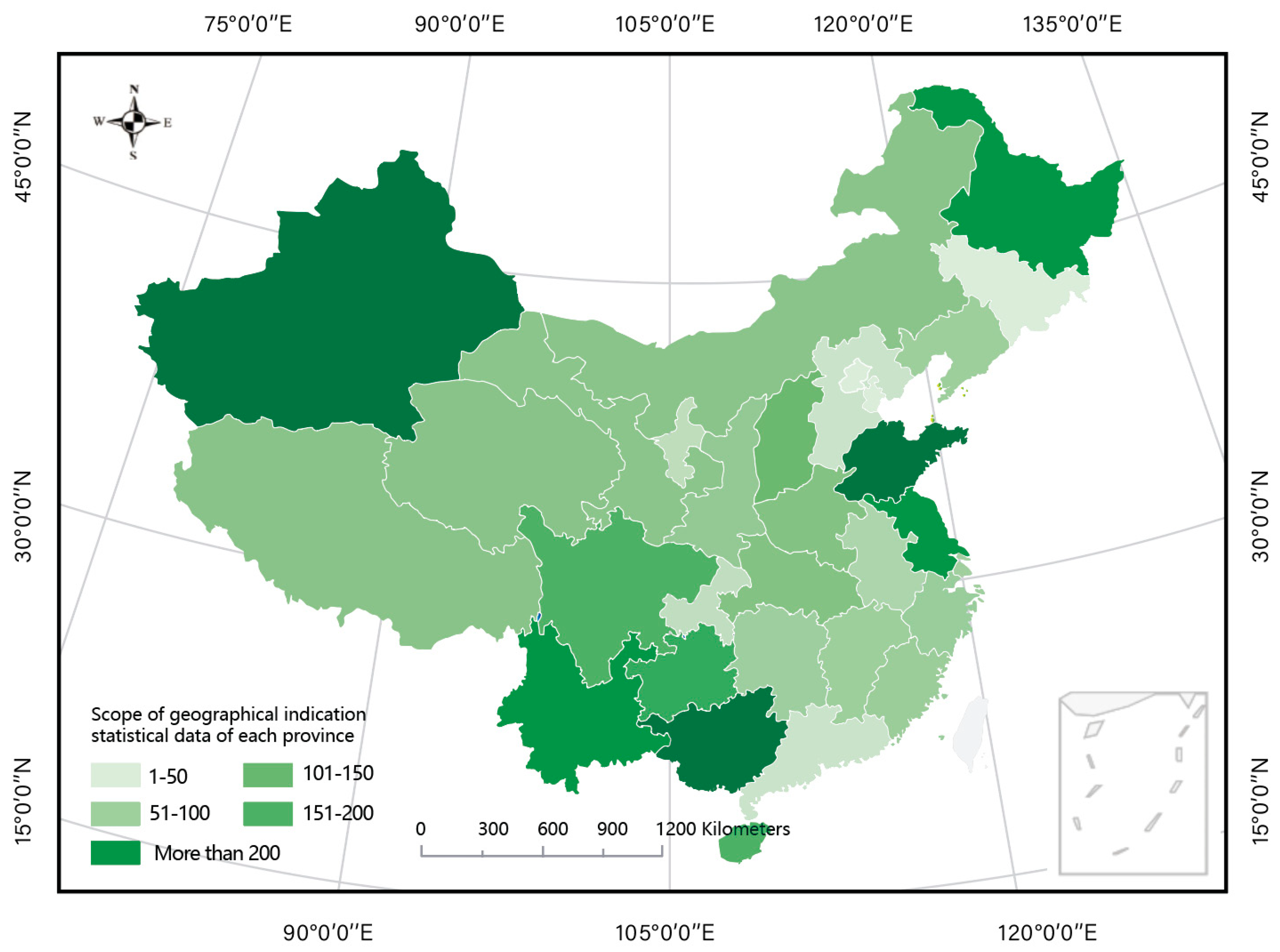

At the institutional level, geographical indications (GI) and traceability systems provide the structural foundation for brand authenticity. As of July 2025, China has recognized 2861 GI products, with more than 9700 included under trademark protection, reflecting the rapid growth of public brand assets [

2], as shown in

Appendix A,

Figure A1. However, implementation discrepancies and “last-mile” gaps continue to cause consumers to question the reliability of traceability systems [

3]. Recent studies highlight that digital traceability and blockchain technologies can enhance transparency and reduce information asymmetry in agri-food supply chains, yet challenges of adoption and consumer interpretation remain [

4,

5].

On the demand side, the popularization of short videos and livestream e-commerce has reshaped consumer behavior. By the end of 2023, the number of livestream users in China had reached 816 million, accounting for over 70% of internet users. While such “short-chain + strong-visual” models improve communication efficiency, they also intensify information asymmetry and experiential mismatches. Recent research on livestreaming commerce suggests that authenticity cues and interactive communication significantly influence consumer trust and conversion behavior [

6]. Similarly, studies on digital transparency in agricultural e-commerce show that verifiable traceability and information disclosure can strengthen trust and perceived value [

7]. In response to these challenges, regulatory authorities issued the Draft Regulations on Livestream E-Commerce Supervision in 2025, marking a shift in governance priorities from “development-oriented” to “precision governance.”

In high-noise markets, label-driven naming may stimulate short-term sales but often results in inconsistent experiences and negative spillovers, which can escalate into skepticism toward the origin as a whole [

8,

9,

10]. Interviews with enterprises and industry experts consistently highlight that while “first-purchase conversion rates are high, repurchase rates are declining,” indicating a structural issue—experiential quality serves as the key mediator linking authenticity and trust. Consumer trust ultimately depends on whether the product’s origin is verifiable, the process is transparent, and the cultural narrative resonates with consumers’ values. Recent works on digital authenticity and influencer marketing further confirm that perceived transparency and credibility are critical psychological mechanisms shaping trust in digital environments [

11,

12].

Despite the growing body of research on agricultural branding, several gaps remain. First, most prior studies emphasize institutional or technological mechanisms of authenticity—such as geographical indications, certification systems, or blockchain-enabled traceability—while paying far less attention to the psychological mechanisms through which consumers perceive authenticity and transform it into trust and purchase intention. Second, existing studies are predominantly based on Western contexts, leaving limited empirical evidence on how these mechanisms operate in China, where livestreaming e-commerce and digital consumption dominate. Third, methodological approaches often rely on single-path SEM or regression analyses, overlooking the potential of combining structural discovery with causal validation to capture heterogeneity in consumer behavior.

To bridge these gaps, this study constructs a psychological mechanism framework centered on Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA) [

13,

14,

15,

16], modeled as a second-order latent construct composed of origin cognition, cultural identification, and brand transparency. Experiential quality (EQ) is similarly conceptualized as a second-order construct encompassing brand, service, and post-purchase experience, working jointly with trust to influence purchase intention [

17]. Within this framework, authenticity functions as the upstream variable driving experience and trust: when evidential signals are consistent, cultural identification is reinforced, and transparent disclosure is achieved, consumers are more likely to form stable trust and repurchase intentions; conversely, inconsistent or unverifiable signals can trigger distrust and negative spillovers.

Based on this framework, the present study adopts a dual-evidence strategy integrating Jaccard similarity clustering and PLS-SEM to connect structural discovery and causal validation [

18]. This approach allows both macro-level pattern recognition and micro-level mechanism testing within the same empirical design. The study further introduces two novel governance tools—“evidence density” and “experiential variance”—to operationalize brand authenticity governance. “Evidence density” captures the concentration and consistency of authenticity signals (e.g., certification, origin disclosure, traceability), while “experiential variance” reflects the degree of stability in consumer experience across multiple touchpoints (brand, service, post-purchase). Together, they form the empirical basis for precision governance in agricultural branding.

Accordingly, this paper addresses three key research questions:

RQ1: How do consumers form perceived brand authenticity through origin cognition, cultural identification, and transparent traceability cues?

RQ2: How does perceived brand authenticity influence purchase intention through experiential quality and consumer trust?

RQ3: Do these paths vary across different consumer groups and contexts?

The contributions of this study are threefold:

- (1)

Theoretical contribution: It reconceptualizes authenticity as a second-order, evidence-based construct, revealing the governance logic of the “authenticity–experience–trust” mechanism and offering a testable psychological pathway for sustainable brand trust formation.

- (2)

Methodological contribution: It employs a dual-evidence approach that combines Jaccard similarity clustering and PLS-SEM, bridging structural pattern discovery and causal mechanism validation.

- (3)

Practical contribution: It introduces two actionable governance tools—evidence density and experiential variance—that translate authenticity into measurable and implementable mechanisms for precision marketing, digital traceability, and sustainable brand governance under the frameworks of SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

3. Research Methods and Data Collection

To strengthen contextual validity, the questionnaire was not designed as a purely abstract survey. Instead, it incorporated prompts of well-known agricultural brands (e.g., Jainong, Dole, Joyvio, Zespri) that possess clear origin backgrounds, established brand systems, and sustained presence across both online and offline channels. Furthermore, the measurement items explicitly included institutional and technological authenticity cues, such as geographical indication (GI) marks, organic/green certifications, and traceability QR codes. This design ensured that consumer evaluations were not detached perceptions, but rather judgments anchored in real institutional signals and technological practices. In this way, the data capture the interface between “objective authenticity mechanisms” and “subjective consumer perception.”

To ensure the contextual validity and practical relevance of the questionnaire measurement, this study introduced brand prompts before the formal survey design in order to simulate respondents’ processes of brand perception, experience, and trust construction in realistic consumption scenarios. Since the study had not yet carried out field promotion for any new brand, four representative fruit brands in both the Chinese and international markets—Jainong, Dole, Joyvio, and Zespri—were incorporated as reference objects to reduce respondent burden and stimulate actual consumption memory. These brands were selected because they possess clear origin backgrounds, relatively mature brand systems, and sustained presence across both online and offline channels, thereby enabling respondents to provide evaluations based on authentic or familiar experiences. In designing the questionnaire, the research team also considered category coverage (e.g., bananas, apples, kiwifruit), origin recognizability, and market trust foundations, all of which enhanced the contextual reliability and external validity of the measurement. The research model and questionnaire design process are illustrated in

Figure 3.

Before beginning the questionnaire, respondents were first asked to confirm whether they were familiar with and had previously purchased any of the listed brands. This design ensured consistency in measurement while partially reconstructing the natural process through which brand perception and purchase intention are formed, thereby enhancing the psychological validity of the data. The approach avoided the imaginative burden associated with entirely hypothetical brands and minimized potential systematic bias arising from individual brand preferences, thus providing a robust contextual foundation for subsequent structural equation modeling and path analysis. In addition to collecting respondents’ demographic information, the questionnaire also captured their agricultural product consumption characteristics, including primary purchasing channels and product attributes of concern, in order to provide a more comprehensive profile of consumer behavior.

3.1. Study Design

This study employed a structured questionnaire, designed on the basis of the theoretical framework and operational definitions of variables, to systematically capture consumers’ psychological response paths within the trust mechanism of agricultural product brands. The overall questionnaire was adapted from established scales and localized through semantic refinement and pilot interviews, ensuring the appropriateness and reliability of the instrument in terms of content validity, construct validity, and discriminant validity.

The questionnaire was organized into four sections: Brand Introduction: Presentation of typical agricultural product brand information to enhance contextual immersion. Demographic Information: Including gender, age, income, household size, and related characteristics. Consumption Characteristics: Covering family roles, primary purchasing channels, and concerns regarding agricultural product certifications. Measurement of Model Variables: Operationalization of core constructs based on validated scales within the research framework. For details, see

Appendix A,

Table A1. Scale Design.

The specific measurements are as follows:

Antecedent Variable—Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA): Conceptualized as a higher-order construct comprising three first-order dimensions:

Place-of-Origin Cognition: adapted from van Ittersum et al. (2003) [

84] and Loureiro & McCluskey (2000) [

85], emphasizing consumers’ knowledge of origin information, regional associations, and perceptions of authenticity;

Cultural Identification: based on Bhattacharya & Sen (2003) [

86] and Tuškej et al. (2013) [

87], assessing whether consumers internalize the cultural attributes embedded in agricultural brands as part of their self-identity;

Brand Transparency: adapted from Schnackenberg & Tomlinson (2016) [

88], combined with traceability and information disclosure requirements in the agricultural sector, measuring consumers’ perceptions of brand openness, consistency, and verifiability.

Mediating Variable—Experience Quality (EQ): Modeled as a reflective second-order construct following Brakus et al. (2009) [

89], Lemke et al. (2011) [

90], and McColl-Kennedy et al. (2015) [

91], comprising three dimensions:

Mediating Variable—Consumer Trust: adapted from Chaudhuri & Holbrook (2001) [

92], Morgan & Hunt (1994) [

93], and Sirdeshmukh et al. (2002) [

94], emphasizing consumers’ confidence in a brand’s fulfillment ability, reliability of promise-keeping, and willingness to reduce perceived risk.

Outcome Variable—Purchase Intention: based on Dodds et al. (1991) [

95] and Yoon (2002) [

96], measured from three aspects: purchase propensity, preference, and recommendation intention.

All items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), which enhanced response sensitivity and variability in accordance with statistical requirements for factor analysis [

97]. Each latent variable contained 3–5 measurement items, yielding an initial pool of 40 items, with the pilot data sources presented in

Figure 4. After two rounds of expert interviews (one each from brand management, agricultural marketing, and consumer psychology) and a small-scale pilot test (n = 56), the clarity of semantics and discriminant validity of the items were confirmed. Ultimately, 34 items were retained, as shown in

Table 1.

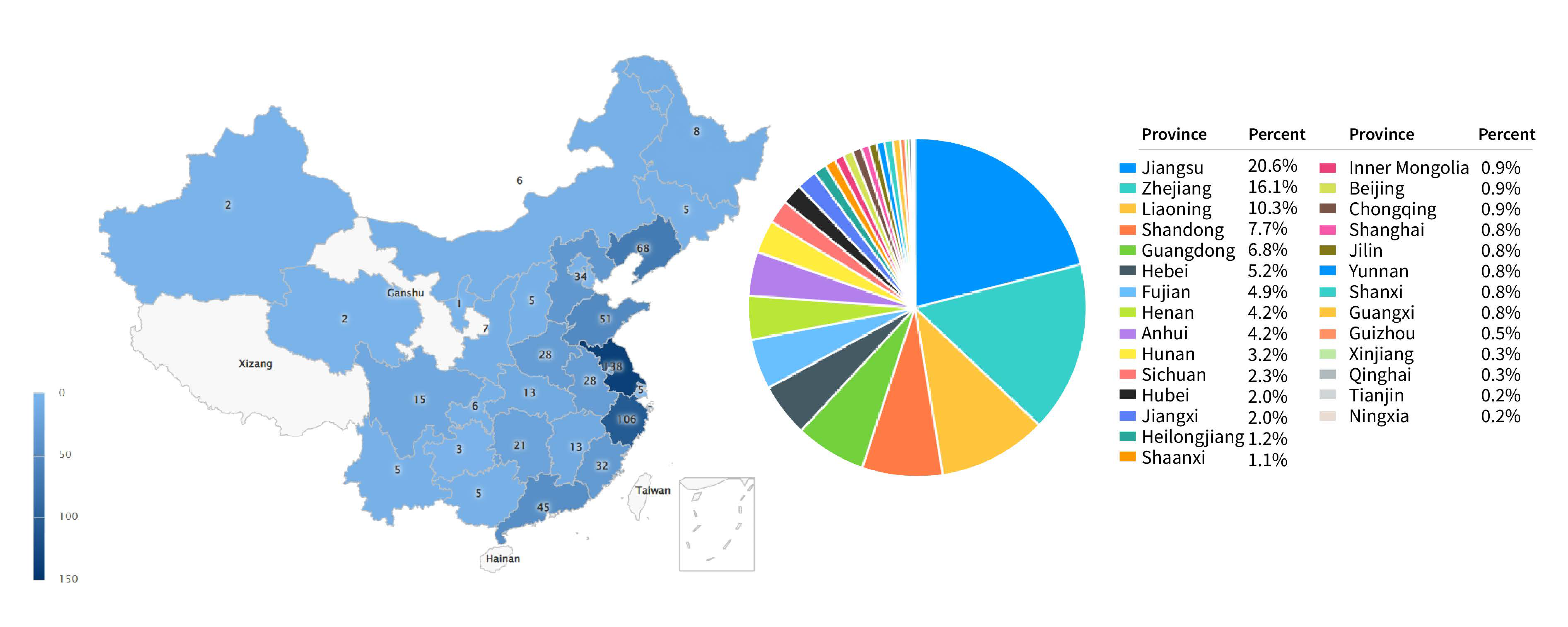

3.2. Data Collection

This study used a structured questionnaire survey to collect data. The questionnaire design was based on an extensive literature review and variable operationalization, covering seven core concepts: perceived origin, cultural identity, brand transparency, perceived brand authenticity, experience quality, consumer trust, and purchase intention. Data were collected between 5 June and 22 August 2025, using a cross-sectional random sampling method through online channels (Wenjuzhixing, social media platforms, and WeChat groups). To improve response quality and participation, small cash incentives ranging from 0.1 to 3 RMB were offered through the online survey platform. Incentive amounts were intentionally kept modest to avoid response bias and excessive incentives. The total expenditure (RMB 1146.2) represented less than 1% of the research budget, meeting ethical standards for non-mandatory remuneration in academic research. This design adhered to the principle of minimal incentives, encouraging genuine participation without altering respondent behavior or response patterns.

In total, 814 questionnaires were obtained, of which 636 valid responses were retained after rigorous screening (validity rate = 78%). The exclusion criteria included: (1) completion time less than 90 s; (2) failure to pass attention-check items; and (3) respondents younger than 18 years old, in order to ensure ethical compliance and the independence of consumer decision-making. The final sample covered 28 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in mainland China, ensuring broad geographic distribution and enhancing the external validity of the study (see

Figure 5).

As summarized in

Table 2, the sample characteristics were as follows: gender distribution—female 58.3%, male 41.7%; age structure—19–30 years (38.8%), 31–40 years (29.1%), 41–50 years (14.6%), and 51 years and above (17.5%), reflecting cross-generational coverage; monthly income—the largest group was RMB 6500–7500 (29.7%), followed by RMB 5500–6500 (20.9%) and RMB 4500–5500 (18.4%), indicating a predominantly mid-to-lower income structure; education—bachelor’s degree (41.4%) and master’s degree (21.4%), with more than 60% of respondents holding higher education qualifications, reflecting strong information-processing capacity and decision-making ability; household size—three-person households (42.8%) and households with four or more members (23.4%). These demographic characteristics closely mirror the profile of China’s online population. According to the China Internet Network Information Center [

98], as of June 2024, China had 1.10 billion internet users and an internet penetration rate of 78%. The latest data reported by China Global Television Network [

99] show that by June 2025, the number of internet users had further increased to 1.12 billion, with a penetration rate of 79.7%. Meanwhile, over 70% of these users regularly engage in online shopping and livestream-based consumption [

100]. Livestream e-commerce has rapidly become mainstream, accounting for approximately 31.9% of China’s total online retail GMV in 2023, up from 17.9% in 2021 [

101]. In addition, China’s e-commerce market continues to expand, with an expected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.9% between 2024 and 2028 [

102].

Given these statistics, the composition of the present sample—mainly digitally active, mid-income consumers—closely aligns with China’s current online consumer structure and the research context of livestream agricultural branding, providing strong external validity for the empirical analysis.

3.3. Data Processing and Tool Selection

This study adopted a multi-stage data processing strategy to conduct multi-level analyses on the valid samples. First, for the multiple-choice items in

Section 2 and

Section 3 of the questionnaire, the Jaccard similarity coefficient was applied to examine the correlations between demographic characteristics and agricultural product consumption traits [

103]. This method helps identify consumers’ combinational preferences across multiple selected factors. Data visualization was performed using R 4.4.3 software. Specifically, a binary matrix was constructed for each multiple-choice item:

where “

n” is the sample size and m is the number of options. If the sample chooses an option, the value is assigned to 1, otherwise it is assigned to 0. Then, the Jaccard similarity coefficient is calculated between any two options to measure their “co-occurrence” in consumer choices:

Here, “

n11” denotes the number of respondents who selected both option “

i” and option “

j”, while “

n1·” and “

n·1” represent the number of respondents selecting each option individually. When the union is zero, the value is treated as missing. From this, a symmetric matrix “

J” was constructed and visualized as a heatmap to illustrate the strength of co-selection relationships. A higher “

J” value indicates stronger co-occurrence between two behavioral or perceptual variables. To ensure interpretive rigor, we applied a cut-off threshold of

J ≥ 0.25, following previous studies on similarity-based clustering in consumer behavior [

104,

105]. Pairs exceeding this threshold were included in the network clustering analysis, while weaker associations were filtered out. The results were visualized through a two-mode co-occurrence network, facilitating the identification of dominant consumer configuration clusters [

101]. When necessary, hierarchical clustering was applied to reorder rows and columns (distance = 1 −

J) in order to highlight cluster structures. Larger values indicate stronger co-selection. Empirically,

J ≈ 0.10–0.20 is considered weak, 0.20–0.30 moderate, and ≥0.30 relatively strong, which allows for the identification of “high-frequency co-occurrence” information patterns [

106,

107].

In addition, to examine heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted by gender, age, income, education, and household size. Within each subgroup, the selection rate for each option was calculated to form a population × option matrix, which was then visualized using heatmaps. For each “population category × single option (0/1)” contingency table, Cramér’s V (range: 0–1) was computed based on χ2 statistics, and options were reported in descending order of V to highlight those with the most significant differences.

In the fourth part of the structured questionnaire analysis, this study employed SPSS 26.0 and SmartPLS 4.0 for data processing and model testing to ensure both the reliability and validity of the measurement scales and the overall model fit. First, SPSS was used to conduct descriptive statistics, item analysis, internal consistency testing (Cronbach’s α), and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), thereby providing a foundation of data cleaning and reliability for subsequent model construction. Next, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was applied to validate the theoretical model. This method systematically examines the path relationships, explanatory power, and mediation effects among latent variables. PLS-SEM has been widely applied in marketing and management research, particularly in studies exploring emergent constructs and predicting behavioral outcomes [

108]. Given that the objective of this study is to reveal how consumers’ perceptions of agricultural brand authenticity influence the formation of trust and purchase intention, PLS-SEM offers a robust modeling framework with strong explanatory and predictive capabilities.

4. Empirical Analysis and Interpretation of Results

To identify structural patterns in consumers’ multiple-choice questions, we applied the Jaccard similarity coefficient, a nonparametric metric that measures the degree of co-occurrence between category choices. The Jaccard similarity coefficient is particularly well-suited to multi-response survey data because it focuses only on common positive choices, avoiding inflation caused by common missingness. It is commonly used in fields such as data mining, text analysis, and bioinformatics.

In this study, each multiple-choice item (e.g., preferred purchase channels, certification types, or product attributes) was transformed into a binary vector, where “1” indicates the option was selected and “0” indicates it was not.

And where “a” represents the number of options both respondents selected, and “b” and “c” represent the number of options selected by only one of the two. The resulting similarity matrix (values ranging from 0 to 1) reflects how closely respondents’ choice patterns align.

Using this matrix, we performed hierarchical clustering to group respondents with similar decision profiles. For example, consumers who frequently selected “e-commerce,” “livestreaming,” and “traceability QR codes” exhibited high Jaccard similarity and were clustered together, whereas those selecting “supermarkets,” “community outlets,” and “organic certifications” formed a separate cluster. This method helps reveal the underlying preference structure in multiple-choice data without relying on distributional assumptions, and can be displayed through a correlation heat map: the darker the color, the more common options there are among the respondents, and the higher the similarity.

4.1. Group Decision Analysis

This study constructed a structural evidence framework across five dimensions: population × shopping role/purchasing channel/certification preference/decision-making factors/premium acceptance. The core methods included selection-rate heatmaps and Jaccard co-occurrence analysis of multiple-choice items. The framework is designed to systematically capture stable patterns and gradient differences among consumer groups (by gender, age, education, and income) in agricultural product purchasing, thereby addressing the questions of “who buys, where, for what reasons, to what extent of premium acceptance, and which factors tend to co-occur.” Compared with approaches that rely solely on means or regression analysis, this method reveals deeper structural information and provides reproducible and quantifiable evidence for subsequent theoretical testing and contextual interpretation.

4.1.1. Comparison of Household Agricultural Product Purchasing Roles by Group

As shown in

Figure 6, household agricultural product purchasing follows a typical “information–decision–execution” chain. In terms of gender, women are more frequently the decision-makers (DC) and purchasing executors (BUYERS), while men are more often engaged as information providers (IP) and simple consumers (SC). Quality supervisors (QS) do not play a central role for either gender. Age analysis indicates that “decision authority rises with age”: older generations are more prominent in DC, while younger cohorts take the lead in BUYERS and IP, forming a collaborative pattern in which “the young gather information, the elders make the final call.” From an education perspective, highly educated individuals are more inclined to participate in IP and decision-making processes, reflecting stronger information search and joint decision-making capacities. Income effects display a “U-shaped” pattern: low-income groups exert greater decision-making authority due to budget constraints, while high-income groups assume stronger leadership because of preferences for health and quality. Overall, this pattern aligns with classical theories of household decision-making and resonates with the digital customer journey: information is “pre-configured” through livestreaming and user-generated content (UGC), transmitted by household influencers, and finalized by decision-makers. Prior studies similarly confirm that in agricultural livestreaming contexts, social presence and interactivity significantly enhance purchase intention through the mediation of trust, which explains the coexistence of “youth as information suppliers” and “elders as ultimate decision-makers.”

Further analysis, as presented in

Table 3, shows that QS and SC occupy relatively minor roles across all groups, suggesting that “quality control” has shifted from intra-household responsibilities to institutional and platform mechanisms. Origin labels, traceability systems, and disclosure of inspection results provide verifiable quality assurance, while reliable logistics and after-sales services transform this assurance into experience quality and trust. Thus, the focus of brand governance lies not in “persuasion techniques” but in the “clarity and consistency of evidence.” Research in food systems also corroborates that consumer trust is jointly constructed through product-assurance pathways (origin, certification, traceability) and system-assurance pathways (accountability of platforms and institutions), with transparency serving as a key input. Particularly in the Chinese context, logistics and after-sales experience significantly improve satisfaction and repurchase intentions, constituting a hard constraint for transforming livestream-driven impulses into stable cross-generational repurchase behavior.

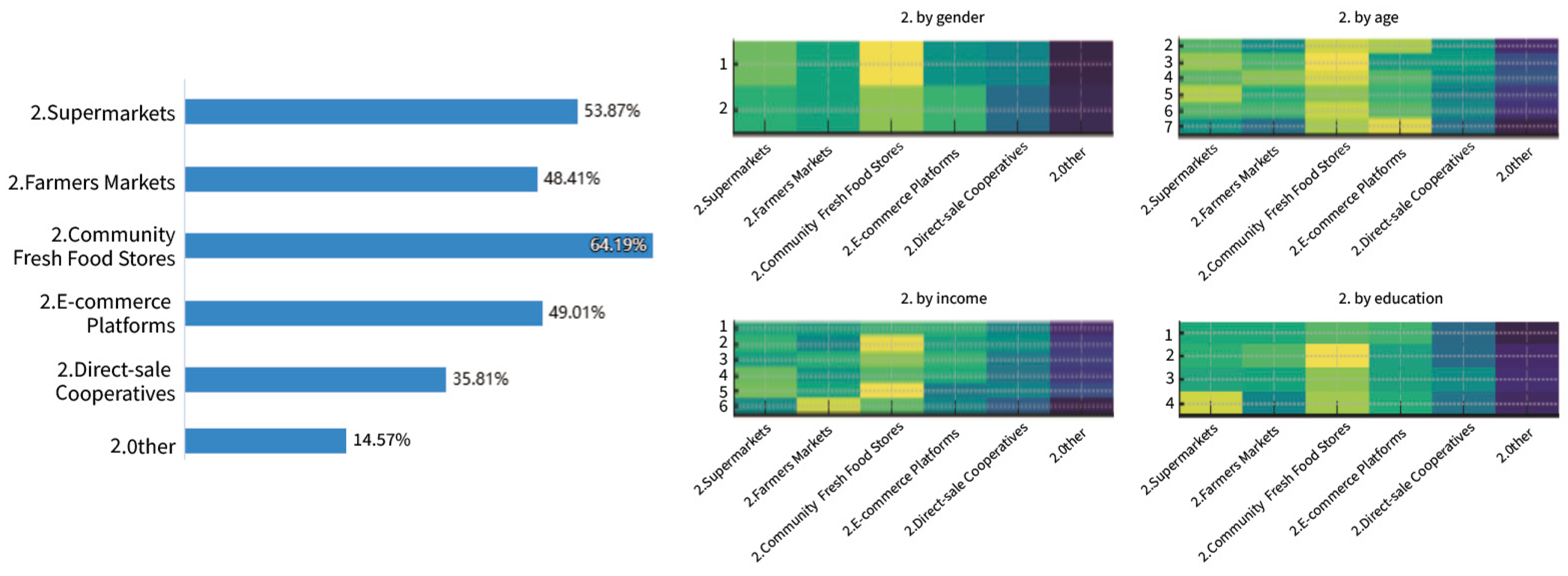

4.1.2. Comparison of Channel Preferences by Group

As shown in

Figure 7, the overall channel structures for men and women are broadly similar, with community fresh markets and e-commerce forming the dual core. The difference lies in that women rely more on offline, immediate-access channels such as supermarkets and community fresh outlets, while men are more active in e-commerce and direct-from-origin purchases. This aligns with the earlier findings on household roles: women dominate decision-making and execution, whereas men and younger members primarily contribute as information providers.

As detailed in

Table 4, clear generational differences emerge in age-related patterns: younger and middle-aged consumers prefer e-commerce (including livestreaming and instant delivery), older consumers are concentrated in supermarkets and community fresh markets, while the elderly retain a preference for traditional wet markets, reflecting their habits of “visual inspection and on-the-spot selection.” Education and income further accentuate channel differentiation: highly educated consumers are prominent in both e-commerce and community fresh markets, pursuing efficiency and information density on the one hand, while valuing immediacy and quality assurance on the other. High-income groups show stronger preferences for direct-sales cooperatives and specialty channels, emphasizing origin-based ties and typicality, whereas middle-income groups exhibit greater elasticity between community fresh markets and e-commerce. Overall, this structure resonates with customer journey research on cross-touchpoint trade-offs and aligns with the “short supply chain–localized trust” literature: offline channels fulfill the need for visual verification and instant access, while online channels attract younger and highly educated consumers through information integration and convenience.

Mechanistically, channel choice can be interpreted as a trade-off among verification costs, time costs, and experiential certainty. Younger and highly educated consumers, with higher levels of digital literacy, rely more heavily on reviews, price comparisons, and traceability disclosures in e-commerce. However, for platforms to convert “impulse buying” into repurchase, stable fulfillment and after-sales services are required to reduce experience volatility. Middle-aged and older consumers prefer supermarkets and community fresh markets, reflecting their need for immediacy and visual assurance. Meanwhile, high-income consumers rely on the relational and place-based trust embedded in direct-sales cooperatives to secure authenticity and typicality.

4.1.3. A Clustered Comparison of Attention Differences in Agricultural Product Certification Marks

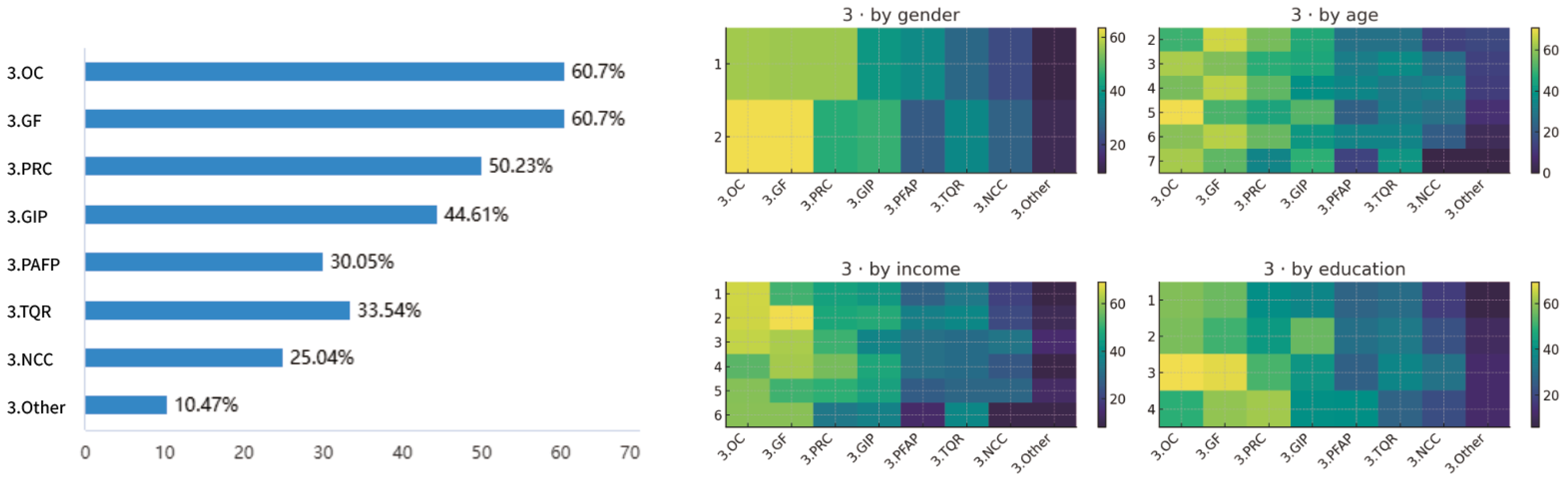

As shown in

Figure 8, based on the “population × certification” heatmap, consumer concerns reveal a three-tiered structure:

Safety and Health Evidence-Oriented: Organic (OC), Green Food (GF), Pesticide Residue Certification (PRC), and Pollution-Free Agricultural Products (PFAP);

Origin and Verifiability-Oriented: Geographical Indication Products (GIP) and Traceability QR Codes (TQR);

Non-Certification Concerned (NCC): serving as the negative baseline.

As detailed in

Table 5, Gender differences show that women pay significantly greater attention to OC, GF, PRC, and PFAP compared with men, while the proportion of NCC is lower, indicating stronger safety sensitivity and preference for evidence. GIP and TQR display limited gender differences, though women still hold a slight advantage.

In terms of age, a clear “life-cycle effect” is observed: middle-aged and older consumers place greater emphasis on OC, GF, and GIP, reflecting experience and health concerns; younger consumers stand out in TQR, relying more heavily on digital traceability; NCC declines steadily with age.

Income and education jointly drive a “preference for evidential signals.” Higher income levels correspond to stronger concern for OC, GF, PRC, and GIP, while TQR is more salient among middle- and high-income groups, accompanied by reduced NCC. Similarly, higher education strengthens attention to TQR, PRC, and OC, while significantly lowering NCC. Consumers with mid-to-high levels of education are especially sensitive to GIP, interpreting it as a dual signal of both origin identity and quality assurance.

Overall, the heatmap highlights three differentiated mechanisms:

Evidence-Oriented (OC/PRC/TQR/PFAP): concentrated among higher-education, higher-income, and middle-aged/older groups;

Identity-Oriented (GIP/GF): combining origin and cultural recognition, favored by middle-to-high income and higher-education groups;

Non-Certification Concerned (NCC): more prevalent among younger, less-educated, and lower-income consumers, reflecting stronger reliance on convenience and price.

4.1.4. Differences in Attention Paid to Factors in Agricultural Product Decision-Making

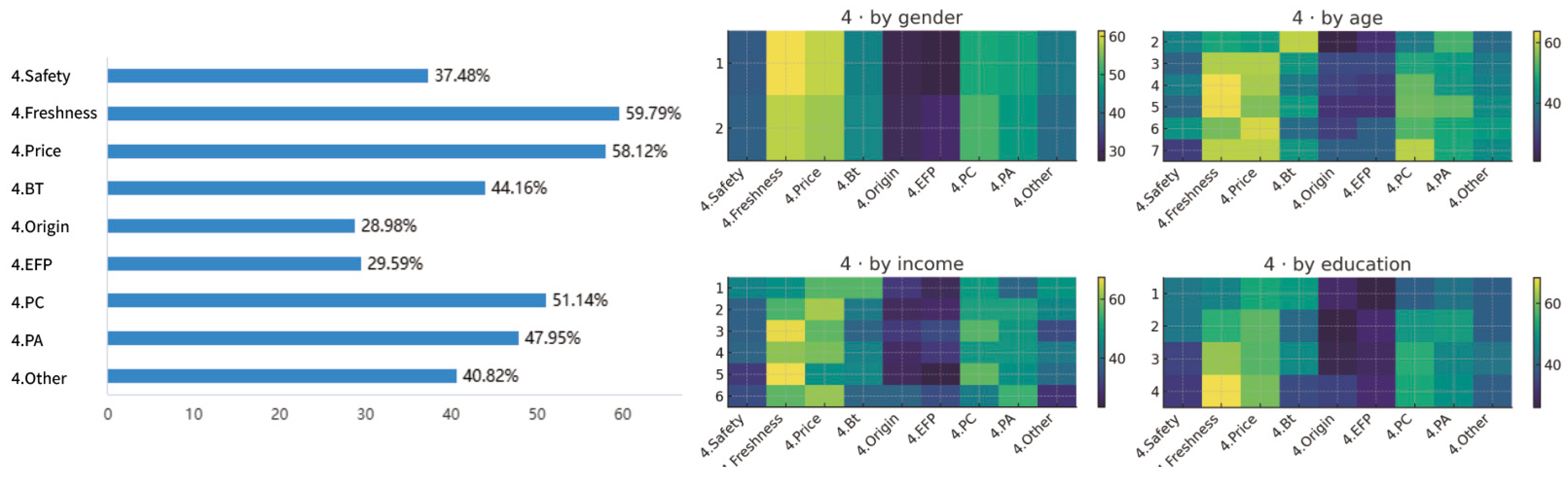

As shown in

Figure 9 and

Table 6, the heatmap reveals a stable “quality–price dual-core” structure: across all groups, freshness and price are consistently prioritized, followed by safety. Convenience and promotion function as tactical levers with varying intensity across groups, while brand trust, origin, and eco-friendly packaging serve as supplementary cues.

By dimension, women, while equally emphasizing freshness and price, place slightly more weight on convenience, promotion, and safety/origin compared with men. Age exhibits a life-cycle gradient—freshness and price are most salient among young and middle-aged consumers, while older groups emphasize convenience and de-emphasize promotion. Income patterns show that price sensitivity is strongest among lower- and middle-income groups, whereas higher-income consumers prefer freshness and convenience and show somewhat greater concern for brand trust and origin. Education enhances preferences for “evidence + efficiency”: highly educated groups continue to prioritize freshness and price while also valuing convenience, with slight increases in safety, origin, and eco-friendly packaging.

Based on these insights, an operational and communication framework can be summarized as “hard values as the foundation, tactical adjustments by segment, and values as supplementary signals.” Specifically:

At all touchpoints: consistently highlight freshness evidence, clear price anchors, and fulfillment commitments;

For elderly groups: emphasize at-home convenience;

For young and middle-aged consumers: combine limited-time promotions and membership-based repurchase incentives;

For lower-income groups: stress price comparisons and bundled offers;

For high-income and highly educated consumers: integrate brand endorsements, origin cues, and environmental packaging to reinforce trust and values.

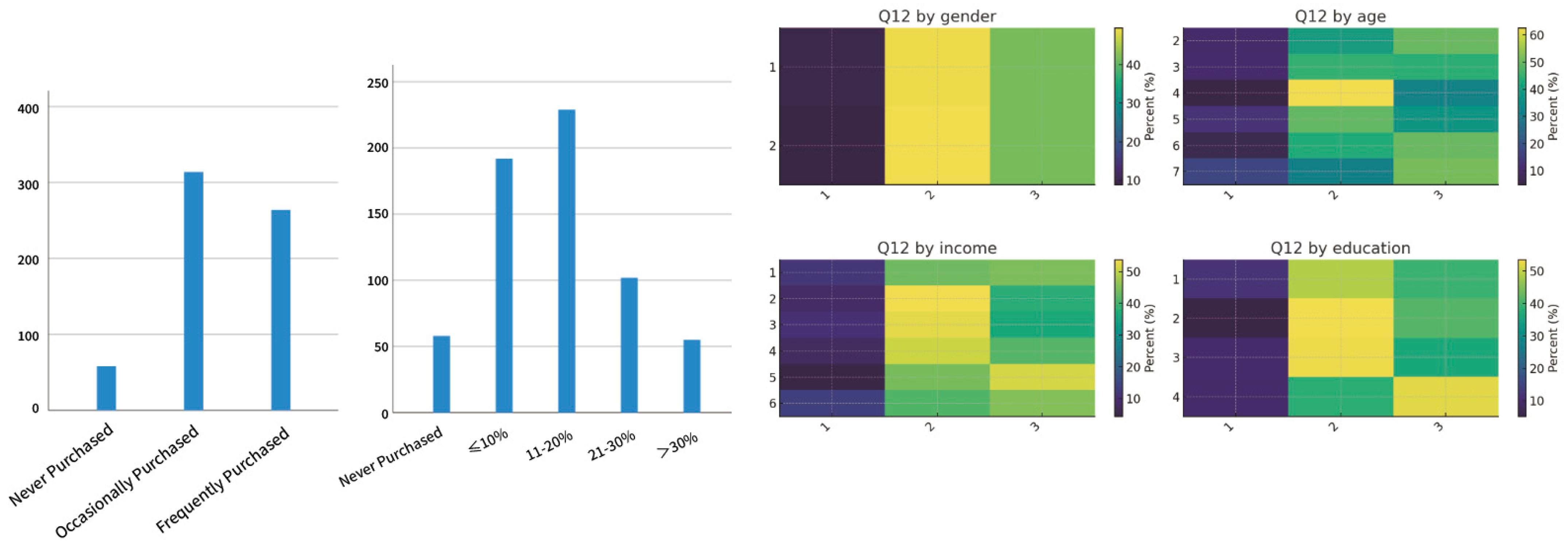

4.1.5. Group Differences in Willingness to Pay a Premium for Branded Agricultural Products

As shown in

Figure 10 and

Table 7, consumer acceptance of price premiums follows a three-tiered structure: the majority accept moderate premiums (brightest in column 2), a minority reject premiums (darkest in column 1), while acceptance of high premiums increases progressively with higher education and income levels (brightening in column 3). Gender differences are overall limited, indicating that willingness to pay brand premiums is not gender-driven. By age, middle-aged consumers cluster around moderate premiums, while both elderly and some younger consumers show considerable acceptance of high premiums, reflecting a cross-generational consensus around “health/safety–certainty.” Education and income display a monotonic progression: the higher the level, the lower the share rejecting premiums, and the higher the proportion accepting high premiums. This aligns with prior China-based evidence, which finds that higher education and income enhance awareness of safety and organics, thereby strengthening premium tolerance (e.g., double-hurdle models for organic fruits and discrete choice experiments for certified pork both confirm the positive effect on willingness to pay, WTP). Overall, the branded agricultural product market exhibits a stratified structure: the mass market generally accepts moderate premiums, while highly educated and high-income groups are willing to pay higher premiums for “stronger endorsements.”

Mechanistically, three payment logics can be identified:

Strong Endorsement Labels → Instant Trust → Premium. Government or third-party certifications, food safety statements, and traceability disclosures significantly raise WTP, with high-trust consumers showing larger premiums.

Origin and Typicality → Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA) → Premium. Origin-based signals such as geographical indications consistently elevate premiums, particularly among highly educated and urban consumers.

Digital Verifiability → Reduced Uncertainty → Migration from Moderate to High Premiums. Meta-analyses of traceability reveal a sustained global increase in WTP; when platforms ensure stable disclosure and logistics fulfillment, the majority of “moderate-premium” consumers can be shifted into the “high-premium” market segment.

4.2. Model Checking

4.2.1. Reliability Test

To ensure that the measurement scales employed in this study demonstrate satisfactory construct reliability and validity, SmartPLS 4.0 was used to evaluate the measurement model of all latent variables. The assessment included tests of indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The results of these tests are presented in

Table 8. See

Appendix A for the scale.

In terms of indicator reliability, all standardized factor loadings of the measurement items were significantly above the threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.827 to 0.947, indicating that each item effectively reflects its corresponding construct and demonstrates strong indicator reliability [

19]. Regarding internal consistency, all latent variables achieved Cronbach’s α values exceeding 0.85, while Composite Reliability (CR) values were all above 0.90, substantially higher than the recommended thresholds of 0.70 and 0.80. These results confirm that the constructs exhibit excellent internal consistency and stability [

93,

94]. Furthermore, convergent validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The results show that the AVE values of all constructs ranged between 0.738 and 0.878, well above the minimum benchmark of 0.50 [

94], suggesting that the constructs successfully capture sufficient variance from their measurement items. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that all latent variables in this study meet the requirements of reliability and convergent validity, providing a solid foundation for subsequent structural model analysis.

4.2.2. Validity Testing

To ensure the discriminant validity of latent variables in the structural model, this study employed two approaches: the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) and the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) of correlations [

95]. First, according to the Fornell–Larcker criterion, discriminant validity is established if the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (√AVE) for each construct is greater than its correlations with other constructs. As shown in

Table 9, the √AVE values (bold diagonal elements) for all constructs were substantially higher than their inter-construct correlations, indicating good discriminant validity.

Second, the HTMT criterion was further applied. Henseler et al. (2015) [

95] suggest that HTMT values below 0.85 indicate satisfactory discriminant validity, while values between 0.85 and 0.90 may still be acceptable. In this study, all constructs exhibited HTMT values well below 0.85, as reported in

Table 10, further confirming that adequate discriminant validity was achieved. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the research model exhibits robust discriminant validity, thereby ensuring the reliability of subsequent structural path analyses.

4.2.3. Multicollinearity Test

In examining the relationships between second-order constructs and their first-order dimensions, PLS-SEM has been widely applied in complex model analysis, theory extension, and small-sample research, demonstrating strong applicability. In this study, Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA) and Experience Quality (EQ) were specified as second-order constructs. PBA was modeled with three first-order dimensions—Brand Transparency (BT), Cultural Identification (CI), and Place-of-Origin Cognition (POC)—while EQ was modeled with three dimensions—Brand Experience (BE), Service Experience (SE), and Post-purchase Experience (PP). A reflective–reflective-type modeling approach was adopted to construct the latent variable paths.

As reported in

Table 11, for measurement evaluation, outer weights, variance inflation factors (VIF), and t-value significance were employed to test the contribution and significance of first-order constructs to their second-order counterparts. The results indicate that all first-order dimensions exhibited outer weights greater than 0.3, with t-values significant at the

p < 0.001 level, demonstrating their strong representativeness and statistical power within their corresponding second-order constructs. In addition, all VIF values were well below the threshold of 5, indicating no multicollinearity and confirming the structural stability of the model [

18]. Collectively, these findings validate the interpretability and rationality of the second-order latent constructs. Thus, the design and evaluation logic of the second-order constructs in this study are supported by solid theoretical and methodological foundations.

4.2.4. Explanatory Power Test

To evaluate the explanatory power of the structural model for endogenous variables, the coefficient of determination (R

2) was calculated for each latent construct. The results show: Brand Experience (BE) R

2 = 0.607, Brand Transparency (BT) R

2 = 0.728, Cultural Identification (CI) R

2 = 0.661, Consumer Trust (CT) R

2 = 0.454, Experience Quality (EQ) R

2 = 0.498, Place-of-Origin Cognition (OR) R

2 = 0.718, Purchase Intention (PI) R

2 = 0.437, Post-purchase Experience (PP) R

2 = 0.675, and Service Experience (SE) R

2 = 0.656. According to Chin’s (1998) criteria (0.19 = weak, 0.33 = moderate, 0.67 = substantial) [

96], most constructs (e.g., BT, OR, PP, SE) exhibit substantial explanatory power, while CT and PI fall into the moderate-to-high range. These results indicate that the overall structural model demonstrates strong explanatory validity and practical significance, particularly in predicting key behavioral outcomes such as purchase intention.

Further analysis of effect sizes (f2) reveals that Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA) has a medium-to-large effect on Experience Quality (EQ) (f2 = 0.995). Its effects on Brand Transparency (BT), Cultural Identification (CI), and Place-of-Origin Cognition (OR) are f2 = 2.678, 1.956, and 2.549, respectively, all at substantial levels, underscoring the prominent contribution of these three dimensions to the overall perception of authenticity. Similarly, Experience Quality (EQ) demonstrates strong explanatory power for Brand Experience (BE) (f2 = 1.547) and Service Experience (SE) (f2 = 1.911), confirming its critical role across stages of the experiential chain. Consumer Trust (CT) exerts a smaller but statistically significant effect on Purchase Intention (PI) (f2 = 0.072), validating its role as a key mediator in the behavioral conversion process.

4.2.5. Direct Effect Test

In the structural path analysis, the direct effects of the key hypothesized paths were examined. As shown in

Table 12, all path coefficients were statistically significant, indicating that Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA), Experience Quality (EQ), and Consumer Trust (CT) exert direct effects on Purchase Intention (PI). These results provide strong support for both the theoretical logic and empirical robustness of the model.

Specifically, the effect of PBA on EQ was significant (β = 0.714, t = 25.397, p < 0.001), suggesting that stronger perceptions of authenticity lead to higher perceived experience quality in subsequent brand encounters. PBA also demonstrated a significant positive effect on CT (β = 0.553, t = 10.261, p < 0.001), showing that authenticity effectively reduces perceived risk and fosters trust in the highly uncertain context of agricultural products. In addition, EQ exerted a significant positive influence on CT (β = 0.153, t = 3.626, p < 0.001), validating the role of high-quality experiences in the trust-building mechanism.

Most importantly, both EQ and CT had significant positive impacts on PI. The path coefficient of EQ → PI was β = 0.503 (t = 11.968, p < 0.001), while CT → PI was β = 0.239 (t = 6.148, p < 0.001). These findings confirm the chained mediation mechanism whereby brand authenticity influences purchase intention through experience quality and trust, offering both theoretical explanation and practical implications for agricultural brand management.

4.2.6. Mediation Effect Test

To further validate the mechanism through which Perceived Brand Authenticity (PBA) influences Purchase Intention (PI), this study employed the bootstrapping method (5000 resamples) to test mediation and chained mediation effects. The results indicate that multiple indirect paths were statistically significant (see

Table 13).

First, along the path PBA → EQ → CT, the indirect effect was 0.110 (t = 3.486, 95% CI [0.052, 0.173], p < 0.001), suggesting that authenticity can indirectly enhance consumer trust through improved experience quality. Second, the indirect effect of EQ → CT → PI was also significant (effect = 0.037, t = 3.114, 95% CI [0.017, 0.062], p = 0.002), indicating that experience quality mediates the effect of trust on purchase intention.

For direct mediation, the most pronounced result was observed for PBA → EQ → PI (effect = 0.359, t = 12.215, 95% CI [0.300, 0.415], p < 0.001), demonstrating that authenticity significantly promotes purchase intention through experience quality. Similarly, the path PBA → CT → PI also showed a significant indirect effect (effect = 0.132, t = 4.815, 95% CI [0.083, 0.190], p < 0.001), confirming that authenticity can drive purchase behavior through trust.

Finally, the chained mediation effect PBA → EQ → CT → PI was also statistically supported (effect = 0.026, t = 2.945, 95% CI [0.012, 0.046], p = 0.003), further validating that authenticity indirectly influences consumer purchase intention via the sequential transmission of “experience quality → trust.”

In summary, all mediation and chained mediation effects within the model were statistically confirmed, indicating that perceived brand authenticity not only exerts a direct influence on purchase intention but also indirectly shapes consumer behavior through multiple transmission paths involving experience quality and trust. These findings underscore the central mechanism of authenticity in agricultural brand consumption decisions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Based on Clustering and Co-Occurrence (Jaccard) Heat Map Analysis

Synthesizing five heatmaps—household roles, core channels, certification preferences, key attributes, and premium acceptance—a consistent evidence gradient emerges. Consumers first anchor their choices in the triad freshness–price–safety, then in institutionalized endorsements (organic, green, pesticide-residue, GI/origin) and traceability QR codes. These signals flow through household decision hierarchies—younger members gather information; elders decide; women execute purchases—into actual buying behavior.

In online environments, the credence attributes of agricultural products intensify reliance on verifiable information and consistent fulfillment to reduce uncertainty [

41]. When origin, traceability, and testing align with reliable delivery and after-sales service, trust strengthens, shifting consumers from moderate to high premium acceptance [

52]. Conversely, a single fulfillment failure may, through social-media amplification, spill over into skepticism toward the entire brand or origin [

49].

This structure parallels the central mechanism PBA (origin cognition × cultural identification × transparency) → EQ (brand/service/post-purchase) → CT → PI, explaining why higher-income and better-educated groups are more responsive to strong endorsements and traceability. The experience-closure loop acts as a bridge that converts perceived into validated authenticity.

Based on the above findings, we propose three testable breakthroughs:

Evidence Density Hypothesis: At equivalent prices, the density of evidence (“origin certification + traceability availability + third-party inspection” in conjunction) positively drives Trust and willingness to pay (WTP) in a nonlinear manner, with a steeper slope observed in online channels;

Dual-Person Funnel: In household decision-making shaped by livestreaming and short videos, information providers (younger members/men) pre-frame expectations through User Generated Content (UGC) and interactive engagement, while decision-makers/executors (women/elders) determine conversion and repurchase based on fulfillment consistency;

Trust Externalities: A single negative post-purchase experience exerts stronger category-level spillover (brand → origin → product type) when tied to high-salience certifications or strong regional brands, whereas a “traceability–compensation–reinspection” mechanism can substantially mitigate such spillovers.

These propositions align with recent findings in livestream commerce (trust mediation), traceability meta-analyses (positive WTP effects), and dual-path food-trust research (product × system assurances). They offer directions for robustness and multi-group analyses (MGA).

Toward a sustainability-oriented action framework (Brand × Platform × Policy):

Live-to-Proof Systems: Ensure that every promise made in livestreaming or product detail pages is mapped to batch-level digital twins (GI/origin → inspection ID → cold-chain trajectory → delivery temperature zone), with scannable traceability cards (TQR) serving as intra-household “secondary persuasion” tools. Public-facing SLA-style KPIs (punctuality, intactness, response speed) should also be disclosed.

Evidence Scoreboards and Trust-Recovery Processes: Standardize scripts such as “guaranteed compensation for damage,” “mandatory refunds for mismatches,” and “return of reinspection reports,” transforming negative experiences into learnable service evidence.

Certification Simplification and Disclosure Enhancement: Streamline overlapping labels, unify core disclosure fields (origin, inspection frequency, key flavor/nutritional indicators), and replace “label stacking” with clarity and accuracy.

Lightweight Blockchain/Trusted Database Deployment: Implement these systems within cooperatives and regional public brands, showing only essential public fields externally while ensuring full accountability internally, and integrate with platform risk-control mechanisms to reduce verification costs and suppress “low-quality noise.”

Such governance mechanisms can stabilize the translation of authenticity (PBA) into consistent experience quality and sustainable trust, thereby supporting SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption) and SDG 8 (Decent Rural Employment). Their technological and governance feasibility has been supported by existing research on transparency, traceability, and trust.

Future research can proceed along two directions: Conduct contextualized experiments or quasi-natural experiments manipulating “evidence density” (GI × traceability × inspection × price) and “fulfillment consistency” to identify the causal strength and thresholds of the PBA → EQ → CT → Pl pathway. Construct a “Trust Behavioral Dataset” by combining platform-side algorithmic and governance data (complaint rates, risk-control flags, cold-chain logs) to test the cross-brand and cross-origin propagation of “trust externalities,” and evaluate the marginal benefits of governance interventions (inspection frequency, disclosure standards).

These approaches not only respond to the core pain point of online retail—“seeing is believing”—but also provide quantifiable institutional levers for the sustainable development of agricultural brands.

5.2. Path Test Analysis Based on PLS-SEM

With the rapid development of the socio-economic environment and the deep penetration of digital marketing, brand communication strategies and consumer touchpoints are undergoing unprecedented restructuring. However, this transformation has also been accompanied by a decline in brand integrity and consumer trust [

1]. In the agricultural sector—closely tied to livelihoods—brands relying on rhetoric or price competition without verifiable support from origin, culture, and values are particularly vulnerable to trust crises [

67].

Against this backdrop, this study proposed and tested ten hypotheses along the pathway “Perceived Brand Authenticity → Experience Quality → Consumer Trust → Purchase Intention.” The PLS-SEM results confirmed significantly positive paths for PBA → EQ, PBA → CT, EQ → CT, EQ → PI, and CT → PI, revealing two mediation effects: “authenticity → experience → trust” and “authenticity → trust → intention.” The strongest links, PBA → EQ and EQ → CT, correspond with the high co-occurrence clusters of “e-commerce × verifiable cues” identified in the network analysis, suggesting that greater evidence density and fulfillment stability enhance the conversion of authenticity into trust and purchasing willingness.

These results demonstrate that agricultural consumption follows an integrated psychological chain—initiated by authenticity perception, reinforced by experiential quality, and driven by trust formation—echoing multi-stage, multi-dimensional processing models in contemporary consumer behavior theory [

70].

Furthermore, this study conceptualizes sustainable brand competitiveness as a progressive logic of evidence assetization (EA) → experiential closure (EC) → trust accumulation. Policy and industry collaboration—such as GI enforcement, label reduction, and enhanced platform disclosure—enable educated and high-income consumers to pay premiums for high evidence density, supporting early investment recovery. For price-sensitive consumers, strategies like smaller packaging and price protection ensure stable experiences and gradually build trust, converting short-term premiums into long-term relational assets.

In conclusion, this study extends the theoretical boundary of perceived brand authenticity (PBA) by verifying its central role in mediating experience and trust mechanisms, and provides actionable pathways for agricultural brands as trust-oriented categories. Practically, brands should begin with authenticity, establish full-chain governance integrating origin, culture, and transparency, and prioritize authentic consumer experiences to achieve sustainable market recognition and long-term value creation.

5.3. Implications for Fresh Produce Marketers and Growers

This study provides several practical insights that can guide agricultural enterprises, cooperatives, and local brand managers in improving trust and market performance. The core logic is summarized in a simple sequence—“Authenticity → Experience → Trust → Purchase/Repurchase.”

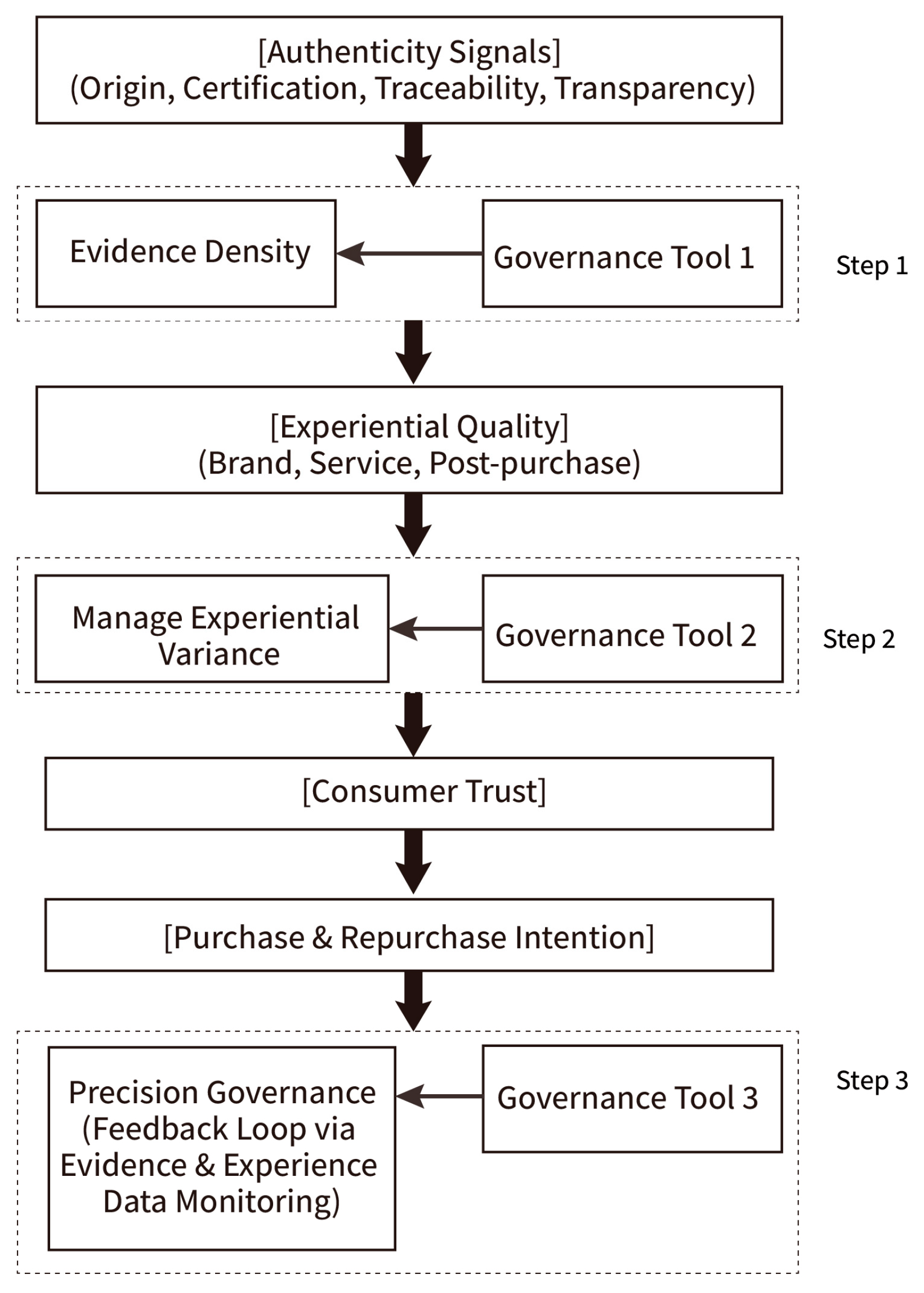

Figure 11 presents this relationship as an intuitive cycle of value creation for agricultural brands.

This figure illustrates how perceived brand authenticity shapes consumer trust and purchase behavior through experiential quality. The framework identifies three actionable governance tools—evidence density, experiential variance management, and precision governance—which together establish a closed-loop mechanism for sustainable agricultural brand development.

Build “Evidence Cards” for Products. Integrate origin, certification, inspection, and traceability data into a unified digital or physical evidence card (e.g., a QR code on packaging). This enables instant verification, reduces confusion from overlapping labels, and strengthens consumer confidence in authenticity.

Stabilize Consumer Experience Across Touchpoints. Consistency outweighs perfection. Product quality, packaging, delivery, and after-sales service should meet uniform standards. Fresh produce enterprises can formalize these through service-level agreements (SLAs) with logistics and retail partners, complemented by instant compensation or reinspection for service failures.

Segment and Target Consumers Precisely. Consumers differ in how they interpret authenticity signals. Younger and educated users value digital traceability and interactive storytelling; middle-aged and older consumers prefer authoritative endorsements and offline assurances; lower-income households prioritize affordability and reliability; and higher-income, sustainability-conscious groups demand eco-friendly packaging and verified certifications. Tailored communication and certification strategies enhance both trust and premium acceptance.

Implement Data-Driven Precision Governance. Enterprises and local authorities should establish a data-feedback loop to monitor authenticity indicators—such as label density, consumer feedback, and complaint ratios—and continuously optimize governance performance. Tools like an Evidence Density Index can quantitatively assess how authenticity signals reinforce trust.

Applying the authenticity–experience–trust framework can shift agricultural branding from short-term promotion to long-term, trust-based value creation, reducing redundant marketing while fostering sustainable competitiveness in China’s fresh produce sector.

Although this study is grounded in China’s agricultural branding and livestreaming e-commerce, its theoretical mechanism extends beyond this context. The authenticity–experience–trust pathway reflects general consumer psychology, but its manifestations are context-dependent. In the European Union, geographical indications (GI) are institutionalized under the Common Agricultural Policy; in North America, consumers rely more on third-party certifications such as USDA Organic or Non-GMO Project. In contrast, Chinese consumers—immersed in livestreaming and digital traceability ecosystems—exhibit heightened sensitivity to real-time verification and service fulfillment.

These variations suggest that while the core pathway from authenticity to trust is generalizable, the specific forms of authenticity signaling (e.g., GI marks vs. blockchain traceability) and channels of experience delivery (offline certification vs. online livestreaming) remain context-dependent. Future research should therefore undertake cross-national comparisons to test the robustness of the evidence density–experimental variance framework across different cultural and institutional settings.

6. Conclusions

This study integrates Jaccard similarity co-occurrence analysis with PLS-SEM path modeling, providing dual evidence of structural discovery and causal verification along the mechanism “Perceived Brand Authenticity → Experiential Quality → Trust → Purchase Intention.”

Two dominant consumer configurations emerge:

- (i)

E-commerce/livestreaming × traceability QR codes × geographical indications × young, educated consumers; and

- (ii)

Supermarkets/community outlets × organic/green certifications × middle-aged and elderly female decision-makers.

Findings confirm that clear origin cues, cultural alignment, and verifiable signals enhance experiential quality and trust, reinforcing purchase and repurchase intentions. In credence-based categories, institutionalized evidence exerts stronger effects on trust than narrative persuasion.

The study advances three theoretical frontiers.

First, it redefines brand authenticity as a governance mechanism rather than a symbolic attribute. By introducing evidence density and experiential variance, it extends marketing theory beyond symbolic communication toward an information governance paradigm emphasizing verifiable signal consistency.

Second, it enriches consumer psychology by complementing and challenging the expectancy–confirmation paradigm, showing that stability across touchpoints—rather than mean satisfaction—drives enduring trust.

Third, it aligns with emerging models of data-driven and sustainability governance, linking micro-level consumer cognition to macro-level institutional accountability.

While authenticity remains central, it interacts with cultural, economic, and platform-specific factors—such as regional norms, income uncertainty, and KOL endorsements—making it a proximal but context-dependent driver of trust and willingness to pay, see

Table 14 for details. Future studies could examine these boundary conditions through cross-cultural or longitudinal designs.

Beyond China, the evidence density–experiential variance framework applies to diverse institutional systems, including EU geographical indications, North American certifications, and blockchain-based traceability in emerging markets. Through evidence assetization → experiential closure → trust accumulation, agricultural brands can transform short-term premiums into enduring trust capital, advancing responsible consumption (SDG 12) and rural employment (SDG 8).

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Focusing on Chinese geographical indication agricultural products, this study develops and validates an integrative framework linking Perceived Brand Authenticity → Experience Quality → Trust → Purchase Intention, demonstrating strong explanatory and predictive power. The theoretical contributions are summarized in six aspects.

First, authenticity is repositioned as a governance mechanism that reduces information asymmetry, modeled as a second-order construct comprising origin cognition, cultural identification, and brand transparency. This shifts authenticity from symbolic to evidential consistency. Second, the study uncovers the causal coupling between authenticity and experience: verifiable signals and transparent disclosure enhance cross-touchpoint experience quality, whereas inconsistencies trigger reverse scrutiny and trust erosion. Third, it clarifies the gateway role of trust, verifying that authenticity and experience jointly drive purchase intention through trust, which serves as the psychological threshold linking authenticity to consumers’ willingness to pay premiums. Fourth, two new governance constructs are introduced—evidence density and experience variance. Evidence density amplifies authenticity effects, while minimizing experience variance—rather than raising mean satisfaction—more effectively stabilizes trust, transforming it into a manageable process variable. Fifth, the study identifies boundary conditions in digital and e-commerce contexts, where the transmission paths from authenticity to experience and from experience to trust intensify, elevating channel effects from control to moderating mechanisms. Sixth, it offers methodological innovation by integrating co-occurrence network analysis with PLS-SEM, bridging “evidence combinations” with “psychological chains” and mitigating the bias of isolated significance tests.

Overall, this study advances an actionable framework for credence-based products: authenticity functions as a governance resource, experience reflects delivery consistency, and trust evolves into accumulated psychological capital that sustains purchase and premium intention.

6.2. Practical Implications

No universal governance model applies uniformly to agricultural branding; governance strategies must be adapted to contextual realities. The findings of this study confirm that perceived brand authenticity functions not as rhetoric but as a governance mechanism that mitigates information asymmetry. To enhance the linkage between authenticity signals and consumer trust, three interrelated strategies are proposed:

(1) Enhancing Evidence Density.

Consumers respond most positively when multiple authenticity cues—such as geographical indications, organic or green certifications, pesticide testing, and traceability QR codes—appear jointly. Firms and policymakers should therefore consolidate origin, inspection, and disclosure data into scannable and verifiable evidence cards, ensuring alignment between promises and credentials across livestream and online channels. An Evidence Density Index may further quantify signal consistency and be integrated into performance assessments to reduce confusion from label proliferation and superficial marketing.

(2) Reducing Experience Variance.

PLS-SEM results show that cross-touchpoint consistency in experiential quality—spanning brand interaction, service fulfillment, and after-sales handling—critically transforms trust into purchase intention. Consumers are more sensitive to fluctuations than to mean satisfaction levels. Establishing clear KPIs, early-warning systems, and remedial actions—such as instant compensation, reinspection feedback, and batch disclosure—can stabilize expectations and strengthen long-term trust through consistently reliable experiences.

(3) Implementing Precision Governance.

Subgroup analyses reveal significant heterogeneity. Women and older consumers value authoritative endorsements and fulfillment reliability; younger and more educated groups prefer traceability, shareable evidence, and comparative data; lower-income consumers emphasize affordability and price protection, whereas higher-income consumers prioritize sustainable packaging and third-party certification. Governance strategies should thus differentiate interventions by demographic profile.

In sum, firms should develop a closed-loop governance framework linking evidence density, experiential stability, and trust accumulation to sustain repurchase and premium retention. Policymakers and enterprises, in partnership with cooperatives and regional public brands, should pursue long-term governance characterized by fewer labels, stronger disclosure, and enforceable accountability.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study draws on cross-sectional survey data from China’s fresh fruit market. Despite applying randomization, psychological separation, anonymity assurances, and collinearity checks to mitigate common method bias, reliance on self-reported, single-source data may still inflate path coefficients. Future research should integrate multi-source evidence—such as transaction logs, logistics data, and after-sales records—and employ longitudinal or experimental designs to capture the dynamic transmission of authenticity, experience, and trust across the pre-, during-, and post-purchase stages. Cross-regional and cross-category studies should also test measurement equivalence to control for cultural and channel variations.

While PLS-SEM suits prediction-oriented, higher-order models, it remains sensitive to endogeneity. Future research could enhance causal identification through instrumental variables, Copula methods, and multi-method convergence. The proposed concepts of “evidence density” and “experience variance governance” also warrant empirical validation—particularly their nonlinear and threshold effects—using A/B testing, quasi-experiments, or discrete choice designs to assess marginal impacts on willingness to pay and repurchase.

Given that even a single mismatch between promise and fulfillment can spill over to the brand or category, future studies may draw on social network causal inference or event-study approaches to quantify the diffusion and repair effects of negative experiences. Moreover, subsequent work should extend beyond purchase intention to construct a supply-chain indicator chain linking authenticity governance → experiential stability → trust capital → operational outcomes → sustainability performance, incorporating variables such as return rates, recall rates, and order stability to assess the governance contribution to responsible consumption.

Finally, although this study relies on consumer self-reports rather than institutional records, perception itself is foundational to the effectiveness of authenticity mechanisms. The impact of certification or traceability ultimately depends on consumer recognition and trust. Thus, consumer-based data provide a necessary complement to institutional analyses. Future research could triangulate this approach with blockchain transaction data, inspection results, and disclosure records to align consumer perceptions with institutional performance.