1. Introduction

Environmental decision-making has long been characterised by a persistent discrepancy between intentions and actions, often referred to as the “intention–behaviour gap” [

1]. While individuals may express strong pro-environmental concern, this is not always translated into everyday practices [

2,

3,

4]. A wide range of factors contributes to this gap, including emotions, ethics, situational constraints, and structural barriers [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Organisational and workplace environments have also been shown to shape sustainable behaviour, highlighting the importance of social and institutional contexts [

9,

10,

11].

At the same time, psychological barriers—sometimes described as the “dragons of inaction”—remain powerful obstacles to behavioural change [

12,

13]. These include motivational and cognitive processes such as moral disengagement, low perceived efficacy, and defensive avoidance in response to risk [

14,

15,

16]. Social norms and ethical framings can either reinforce or undermine sustainable choices, illustrating the central role of internalised values in mediating between concern and action [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Situational factors, such as price, product availability, and the credibility of eco-labels, further affect the likelihood of sustainable consumption [

21,

22]. Environmental concern itself is not uniform, but somewhat varies across societies. Research has demonstrated that post-materialist values are associated with higher ecological engagement [

23,

24]. This suggests that sustainable behaviour must be understood as the product of interactions between personal dispositions and contextual cues.

A crucial perspective in this regard concerns the dual roles individuals may assume as both citizens and consumers. Civic framings have been shown to foster collective orientations towards environmental responsibility, while market-oriented framings often encourage short-term, self-interested choices [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. This duality has been explored through experimental approaches, including “green games” and social dilemma paradigms, which highlight how cooperation, punishment, and peer dynamics shape environmental outcomes [

30,

31,

32]. More recent work emphasises that sustainable behaviour is strongly contingent on contextual framing rather than on stable preferences alone [

33,

34,

35].

Nevertheless, much of this evidence has relied on attitudinal surveys or highly stylised dilemmas, which may not fully capture latent motivational dispositions. Scholars in behavioural economics and environmental psychology have therefore called for designs that operationalise sustainability preferences through observable decisions, reducing the limitations of self-report measures [

36,

37,

38]. Practice theory further reinforces the need to view behaviour as embedded within social roles, institutional contexts, and adaptive routines [

39,

40].

Against this background, the present study introduces the construct of Eco-Preference, derived directly from behavioural choices observed under experimental conditions. Unlike self-reported measures, Eco-Preference reflects latent motivational states that manifest in decision-making when individuals face situational trade-offs. Our design, grounded in the decision-making process model [

41] and implemented via the oTree experimental platform [

42], integrates role framing and environmental risk framing to examine how identities and contexts jointly shape sustainability choices.

The following questions guide this study:

RQ1: How do role framings (citizen, consumer, neutral) influence Eco-Preference in sustainability dilemmas?

RQ2: How does environmental risk framing (low, high, neutral) affect Eco-Preference, both directly and indirectly?

RQ3: Do role and risk framings interact in shaping pro-environmental decision-making?

On this basis, we hypothesise:

H1:

Activating a citizen role will increase Eco-Preference relative to consumer and neutral framings.

H2:

High-risk environmental contexts will influence Eco-Preference indirectly, via motivational pathways, rather than through direct effects.

H3:

The interaction of role framing and risk framing will amplify the likelihood of sustainable choices.

In summary, by combining role and risk framings within a behavioural paradigm, the present study contributes to bridging the gap between attitudinal research and experimental approaches to sustainability. The introduction of Eco-Preference as a behavioural construct provides a novel lens through which to capture the latent motivational foundations of ecological responsibility. In doing so, the study not only advances theoretical debates on the interplay between identity, context, and responsibility but also offers a methodological innovation with implications for policy, organisational practice, and cross-cultural research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Everyday Decision-Making

There is a persistent gap between individuals’ pro-environmental intentions and their actual behaviours, often referred to as the “intention–behaviour gap.” This gap is shaped by a constellation of personal, contextual, organisational, and structural factors that can either enable or inhibit sustainable action [

1,

43]. Individual decisions regarding energy use, transportation, and consumption have a significant influence on ecological outcomes and the trajectory of sustainability transitions [

44]. However, even when individuals report high levels of environmental concern, psychological and situational barriers frequently constrain action.

Research shows that perceived behavioural control, trust in policy effectiveness, and situational moderators such as price, product availability, and eco-label credibility strongly influence whether intentions translate into behaviour [

45,

46]. Organisational cultures and peer norms also matter: supportive environments foster sustainable choices, whereas bureaucratic or social resistance undermines them [

47]. Psychological dimensions—including moral obligation, ethical values, and emotions such as pride and guilt—can motivate ecological actions. However, structural barriers such as income or accessibility may still prevent behavioural consistency [

48].

Pro-environmental behaviours are further differentiated by sociodemographic and contextual factors such as age, gender, education, occupation, residence, and direct contact with nature [

49]. Emotional salience, temporal distance of climate risks, and perceived inconvenience also influence engagement [

50,

51]. Importantly, barriers are rarely isolated; instead, they interact to reinforce resistance, underscoring the need for holistic approaches that combine situational enablers, institutional reforms, and socioemotional support. Thus, pro-environmental action must be understood not only as a function of knowledge or motivation, but as a form of internalised responsibility shaped by how individuals perceive their roles within broader ecological and institutional systems.

2.2. Environmental Responsibility and Role-Based Framing

Environmental responsibility is deeply tied to the social roles individuals inhabit and the ways these roles are framed. Practice theory suggests that sustainable consumption cannot be adequately explained by rational-choice or attitudinal models alone, but must be analysed within social practices where routines, expectations, and material contexts co-constitute behaviour [

24]. From this perspective, individuals are “carriers of practices,” and behavioural change emerges when agency is reframed through role identities embedded in social and cultural structures.

One influential distinction is the framing of individuals as citizens versus consumers. Research indicates that when ecological actions are presented as civic duties rather than market choices, individuals tend to adopt more collective and long-term orientations [

50,

51]. However, role ambiguity and diffused responsibility can weaken engagement, particularly when individuals perceive limited efficacy in addressing global challenges [

50,

52]. Effective interventions, therefore, require both structural support and a reframing of agency to highlight meaningful and actionable roles.

Cross-cultural studies add further nuance, demonstrating that ecological values and behaviours vary widely across societies. Franzen and Vogl [

53] demonstrate substantial cross-national differences in environmental concern, while Milfont and Schultz [

54] identify cultural orientations, such as collectivism, as predictors of stronger ecological norms compared to individualism. Evidence from the World Values Survey indicates that post-materialist values, more prevalent in advanced democracies, reinforce environmental concern [

55]. Affluence and ecological degradation further interact in shaping attitudes [

56]. Recent research demonstrates that ecological identity scales retain validity across diverse societies [

57] and that social identity predicts ecological behaviour globally, as shown in data from 48 regions [

58]. Moreover, collectivist orientations have been linked to both sustainable investment patterns [

59] and the effectiveness of environmental regulation [

60]. Comparative studies further reveal how biospheric values and identity predict behaviour differently across cultural contexts [

61]. Reviews of cross-cultural environmental psychology reinforce that constructs such as Eco-Preference must be embedded within a culturally sensitive framework [

62].

Taken together, these insights highlight the importance of role-based framing, responsibility attribution, and cultural heterogeneity in explaining pro-environmental behaviour. Rather than treating individuals as passive recipients of information or incentives, this perspective emphasises their active interpretation of ecological responsibility through socially defined roles. It also provides strong theoretical support for the hypothesis that internalised identity as “planetary citizens” mediates sustainable choices more effectively than abstract informational appeals or urgency-based messaging.

2.3. Risk Perception and Sustainability Decisions

Perception of environmental risk, particularly in the context of climate change, plays a critical role in shaping pro-environmental behaviour. Van der Linden [

28] proposes a comprehensive model, the Climate Change Risk Perception Model (CCRPM), which integrates cognitive, affective, and social dimensions to explain how individuals interpret and respond to climate threats. Rather than treating risk as a purely rational assessment of probabilities, the model acknowledges the influence of personal experience, emotions, value orientations, and perceived social norms.

Importantly, van der Linden’s findings suggest that individuals who perceive higher climate risk are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviours, particularly when this perception is embedded in a socially validated and emotionally resonant framework. Such insights support our hypothesis that environmental urgency alone does not directly produce behavioural change; instead, its influence is mediated by psychological constructs such as identity, responsibility, and motivation—components captured in our conceptualisation of Eco-Preference.

Complementing this perspective, Slovic [

29] introduced the notion of risk as a moral and affective trigger, arguing that risk perception is not merely based on objective information but is profoundly shaped by emotional and psychological responses. In his seminal study, Slovic [

29] demonstrated that people often assess risks not through statistical reasoning, but through visceral reactions such as fear, dread, or anxiety. He introduced key distinctions between “dread risks” and “unknown risks,” showing that risks perceived as catastrophic, uncontrollable, or poorly understood tend to evoke stronger emotional responses and, consequently, greater public concern. These emotionally charged perceptions are more likely to trigger protective and prosocial behaviours, such as taking precautionary action or collective mobilisation. In sustainability contexts, this implies that communicating climate risk in ways that resonate morally and emotionally may be more effective than purely factual or technical narratives.

The perception of environmental risk is also dynamic, shaped by a changing reality. Scholars note that the salience of climate issues can be moderated by competing crises, including geopolitical conflicts and economic instability, which tend to re-order public spending priorities and defer regulatory action on environmental impacts [

28,

33]. The variability of risk perception is certainly an area worth exploring, as current and future conflicts will influence the scale of environmental protection efforts, especially if these actions require significant expenditures.

However, the effects of risk perception are not uniform. The social context strongly moderates how individuals interpret and respond to environmental threats. For example, in communities where ecological concern is not normalised or where climate denial is prevalent, even high personal risk perception may fail to translate into action. Conversely, in supportive environments, moderate risk cues may be sufficient to activate strong pro-environmental responses. This variability reinforces the need for context-sensitive approaches to risk communication and underscores the importance of social framing in mediating behavioural outcomes. Over time, such risk-driven responses, filtered through social and psychological processes, contribute to the formation of environmental culture, where values and practices become embedded in everyday life.

2.4. Formation of Environmental Culture

Environmental culture is not merely a collection of individual behaviours but a complex interplay of values, habits, and social norms that evolve. Inglehart’s [

30] theory of post-materialism posits that as societies achieve greater economic security, individuals shift their priorities from materialistic concerns to values emphasising self-expression, quality of life, and environmental protection. This transition reflects a broader cultural evolution where environmentalism becomes a core component of societal values, particularly in affluent societies where basic needs are met.

Complementing this perspective, Schultz [

31] identifies three primary value orientations influencing environmental concern: egoistic (self-interest), altruistic (concern for others), and biospheric (concern for the biosphere). His research demonstrates that individuals with strong biospheric values are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviours, suggesting that fostering such values is crucial for cultivating an environmentally responsible culture.

Cognitive and social mechanisms further influence the formation of environmental culture. Habits, once established, become automatic responses to environmental cues, making them resistant to change. Research indicates that habit formation involves cognitive and attentional processes, and altering these habits requires both ecological pressures and internal motivation [

32]. Social norms and peer influences play a significant role in shaping these habits. Studies have demonstrated that social norms can effectively motivate sustainable actions and behaviours aimed at mitigating climate change [

33]. For instance, when pro-environmental behaviours are normalised within a community, individuals are more likely to adopt similar practices. Additionally, educational initiatives and public awareness campaigns can alter perceptions and encourage sustainable behaviours by highlighting the collective benefits of environmental stewardship [

34].

Structural factors, such as institutional policies and societal roles, interact with personal values to shape environmentally responsible behaviour. Policies that incentivise sustainable practices can reinforce individual commitments to environmental values [

33]. Moreover, when individuals perceive their roles—be it as citizens, consumers, or community members—as integral to environmental outcomes, they are more likely to engage in behaviours that align with ecological sustainability [

35]. While these cultural and structural foundations are essential, empirical insight into how such dynamics emerge and interact at the individual level comes from experimental approaches.

2.5. Conceptual Distinction of Eco-Preference

Building on the preceding discussion of role identity, situational framing, and perceived risk, it is essential to clarify how the construct of Eco-Preference differs from established concepts in the environmental psychology and behavioural economics literature. While constructs such as environmental concern [

63] and ecological self-identity [

48,

64] have been widely employed to capture individuals’ orientations towards ecological issues, they do not fully account for the motivational dynamics that drive actual pro-environmental choices in situational trade-offs. Environmental concern reflects a generalised worry about ecological degradation, yet research indicates that such concern does not necessarily translate into consistent behavioural outcomes [

53]. Similarly, environmental self-identity refers to the degree to which individuals perceive themselves as “the kind of person who acts pro-environmentally”, but this self-concept is often mediated by contextual cues and social roles [

48]. By contrast, we introduce the notion of Eco-Preference to denote a latent motivational disposition that manifests directly in behavioural choices when individuals are confronted with competing options. Unlike abstract attitudes or self-identifications, Eco-Preference is inferred from observed decision-making under varying frames of risk and role salience, thereby offering a bridge between identity-based constructs and measurable behavioural responses.

Table 1 contrasts Eco-Preference with established constructs, showing that it captures situational motivational dispositions rather than abstract attitudes or identity labels.

Figure 1 illustrates how general ecological values translate into environmental concern and subsequently into environmental self-identity. While both constructs are well-established in the literature [

48,

63,

64], they often remain at the attitudinal or identity level and do not necessarily result in consistent action [

53]. The proposed construct of Eco-Preference captures a latent motivational disposition that mediates the link between identity and observable choices, thereby serving as the immediate predictor of sustainable behaviour in situational trade-off contexts.

2.6. Experimental Approaches to Pro-Environmental Decision-Making

Experimental methods in environmental economics have provided valuable insights into the mechanisms that drive pro-environmental behaviour. Cason and Gangadharan [

36] conducted laboratory experiments to examine how peer punishment influences cooperation in nonlinear social dilemmas, finding that while peer punishment can promote socially efficient behaviour, its effectiveness varies depending on the complexity of the environment.

Brent et al. [

37] reviewed various field experiments in environmental economics, highlighting how interventions such as framing and social norms can effectively promote sustainable behaviours. Hoffman et al. [

38] identified factors that limit pro-environmental behaviour using online laboratory experiments with a large sample of 800 people. According to the authors, the likelihood of such behaviour decreases when individuals are not immediately affected by environmental damage or when the consequences are uncertain. One reason for this is the high personal discount rate used for proximate events.

The use of experimental methods is made possible by the achievements of behavioural economics, whose applications in the field of environmental protection are numerous and well-documented. Rankine and Khosravi [

39], as well as Puzon [

40], present a review of the application of behavioural economics to addressing sustainable development issues.

In modelling decision-making processes, softmax and logit models are frequently employed to capture the probabilistic nature of human choices. These models account for the stochastic elements in decision-making, reflecting how individuals weigh different options under uncertainty. For instance, the softmax function has been used to model sub-optimal, noise-perturbed decision-making, where stochasticity arises due to various factors influencing choice behaviour.

While existing literature highlights stable determinants of ecological behaviour, few studies have experimentally tested how contextual signals such as social role and environmental risk shape the formation of ecological responsibility in everyday decision-making. Moreover, the link between such micro-level adaptive behaviour and the emergence of pro-environmental culture remains largely unexplored. By addressing this gap, our study helps bridge the theoretical insights with empirical evidence, providing a more comprehensive understanding of sustainability transitions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Design

We implemented a scenario-based behavioural experiment titled “Choices in Transition: A Sustainability Decision Game” to investigate decision-making under trade-offs involving sustainability, cost, and social responsibility. Each participant completed three sequential decision rounds, with each round combining an environmental risk condition (randomly assigned as low, high, or neutral risk) and a social role condition (within-subject rotation between consumer, citizen, and neutral roles). Environmental risk was operationalised at three levels: high, low, and neutral. In the high-risk condition, participants were informed about severe and potentially irreversible environmental threats in their area. The low-risk version referred to minor and reversible risks, while the neutral condition omitted any ecological information, serving as a baseline.

Participants were exposed to brief vignettes describing realistic sustainability dilemmas (e.g., purchasing decisions, urban policy preferences), followed by a binary forced-choice task. In all decision rounds, Option B represented the pro-environmental choice, while Option A corresponded to the baseline alternative. This coding ensured consistency across vignettes and allowed Eco-Preference to be operationalised as the frequency of sustainable selections. After each decision, participants provided Likert-type responses on perceived environmental relevance, moral concern, and personal responsibility. A post-game questionnaire collected demographic data and social preference measures, including altruism and social trust. The game’s design was inspired by the decision-making process model, which considers changes in individual preferences, as presented by Liashenko [

41]. For transparency,

Appendix A provides illustrative vignettes and a schematic overview of the role–risk–dilemma structure.

3.2. Game Implementation via oTree

The experiment was implemented using the oTree platform [

42], an open-source framework for real-time behavioural experiments in economics. Each participant completed the game online using their personal devices or university facilities. The platform enabled us to control the random assignment of environmental states across rounds and to implement a within-subject role rotation in a fully automated manner. Session data included exact response times, choice histories, and structured metadata for each condition. The participant pool comprised undergraduate students, graduate students, and university faculty members from diverse disciplines. Participation was voluntary, and no financial incentives were offered. All procedures complied with institutional ethical guidelines and received IRB approval.

The oTree game structure featured: (1) Three rounds with randomised environmental framing per round, (2) Alternating roles per participant (consumer/citizen/neutral), (3) Embedded text-based vignettes and decision forms, (4) Automated logging and export of decision data for Bayesian analysis.

Theoretical Framework. We adopt a context-sensitive framework in which choice strategies π are shaped by adaptive preferences

P, influenced by environmental state S and social role R. The choice probability was modelled using a logit-based

softmax function:

where

Ui represents the subjective utility of option

i, and

β is a sensitivity parameter capturing the degree to which utility differences translate into deterministic choice. Larger values of β indicate higher responsiveness to utility gaps, while smaller values reflect increased randomness or indifference. Utility

Ui was treated as a function of cost, contextual moral relevance, perceived social value, and role-induced preference shifts:

This structure enables modelling of contextually modulated strategies under bounded rationality.

Unlike conventional Green Game or social dilemma designs, our experiment combines role framing and risk framing within a single behavioural paradigm. By activating either a citizen or consumer role and simultaneously manipulating perceptions of environmental risk, we can observe how multiple layers of identity and context interact to shape sustainable decision-making. Moreover, the construct of Eco-Preference is derived directly from participants’ behavioural choices during the game rather than from self-reported attitudes or survey items. This approach provides a latent behavioural indicator that captures motivational dispositions expressed under situational trade-offs. In doing so, the design advances beyond attitudinal measures by operationalising sustainability preferences in terms of actualised decisions, thereby extending the methodological scope of experimental research on pro-environmental behaviour.

3.3. Statistical Modelling

Choices were analysed using a Bayesian logistic regression model implemented in PyMC. The model included fixed effects for environmental context, social role framing, and their interaction. A weakly informative prior (Normal (0,1)) was used for all coefficients, and posterior distributions were estimated using MCMC sampling (2 chains, 1000 draws each, 1000 tuning steps). Marginal effects and 95% Highest Density Intervals (HDI) were extracted for interpretation. This approach enables direct probabilistic statements about the impact of contextual variables on pro-environmental decision-making, supporting uncertainty-aware inference.

To explore causal mechanisms, we specified a structural mediation model, estimating direct and indirect effects from contextual framing to decision outcomes via latent preferences. Model parameters were estimated using weakly informative priors and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling (4 chains, 4000 iterations).

To ensure the robustness of our results, we included socio-demographic covariates (age and role: student vs. lecturer) as controls in all models. We estimated both logistic and probit specifications with cluster-robust standard errors at the participant level to account for within-subject dependence. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF); all values were below the conventional threshold (VIF < 10). Results were consistent across link functions, confirming the stability of our findings (see

Appendix B).

The sample size justification was based on Monte Carlo simulations of parameter recovery. With N = 100–150 participants each completing multiple rounds, sensitivity parameter estimates (β) stabilised, ensuring model robustness.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

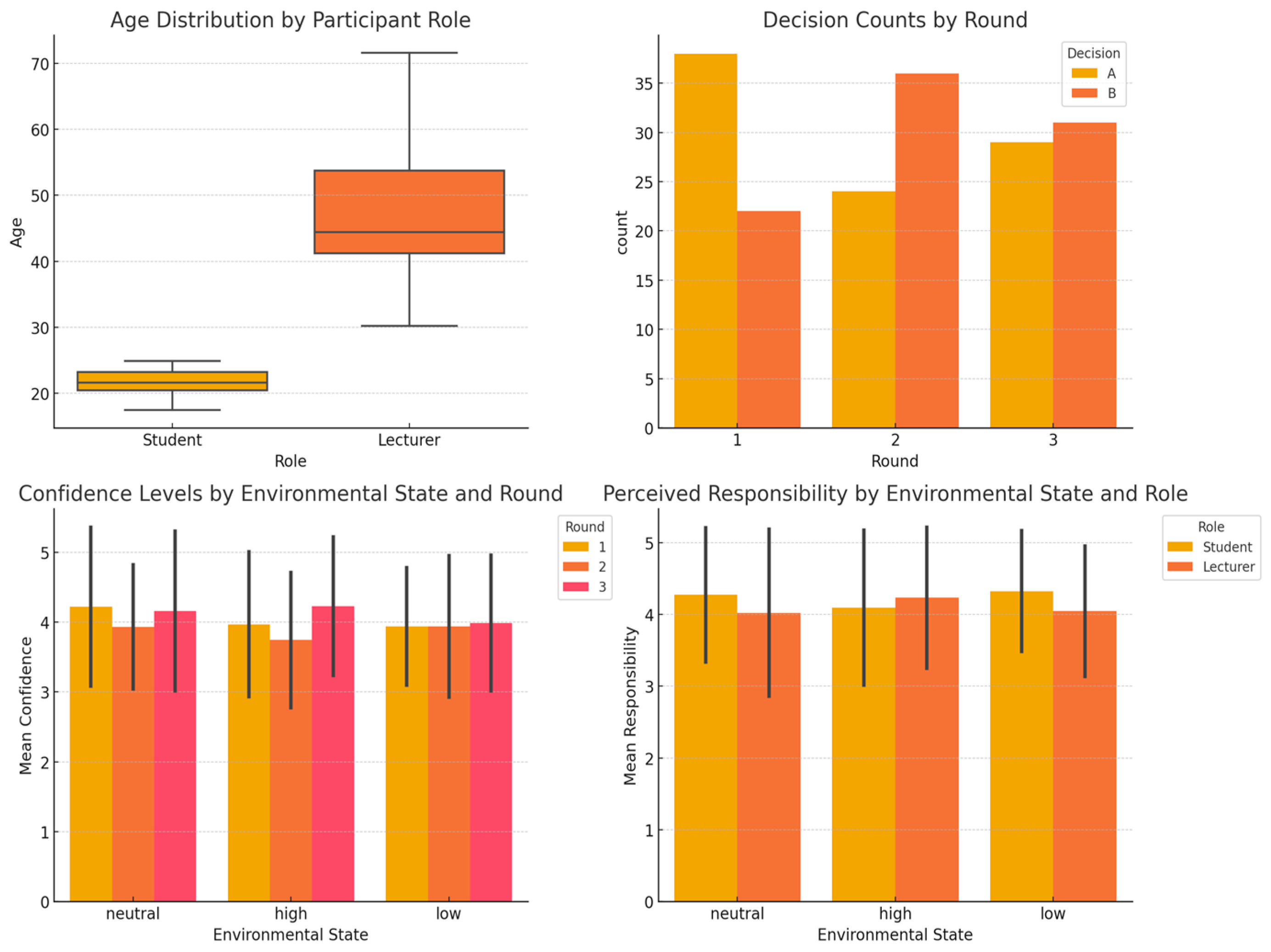

The final experimental sample consisted of 160 participants, with approximately 70% self-identifying as students and 30% as university lecturers. As expected, students were younger (M = 21.1 years, SD = 1.6), while lecturers had a broader age range (M = 42.7 years, SD = 10.2), as illustrated in

Figure 2 (top left).

Across the three decision rounds, participants made binary sustainability-related choices under varying roles and environmental framing. As shown in

Figure 2 (top right), the distribution of decisions (Option A vs. B) remained relatively balanced across rounds, indicating no default bias toward one option.

Confidence ratings were generally higher in low-risk environmental states and showed slight variation across rounds (

Figure 2, bottom left), suggesting that contextual stability may foster greater certainty in choice-making. Perceived responsibility scores were highest under high-risk environmental framing, particularly when participants were in the citizen role (

Figure 2, bottom right), supporting the idea that contextual signals activate normative reasoning and accountability.

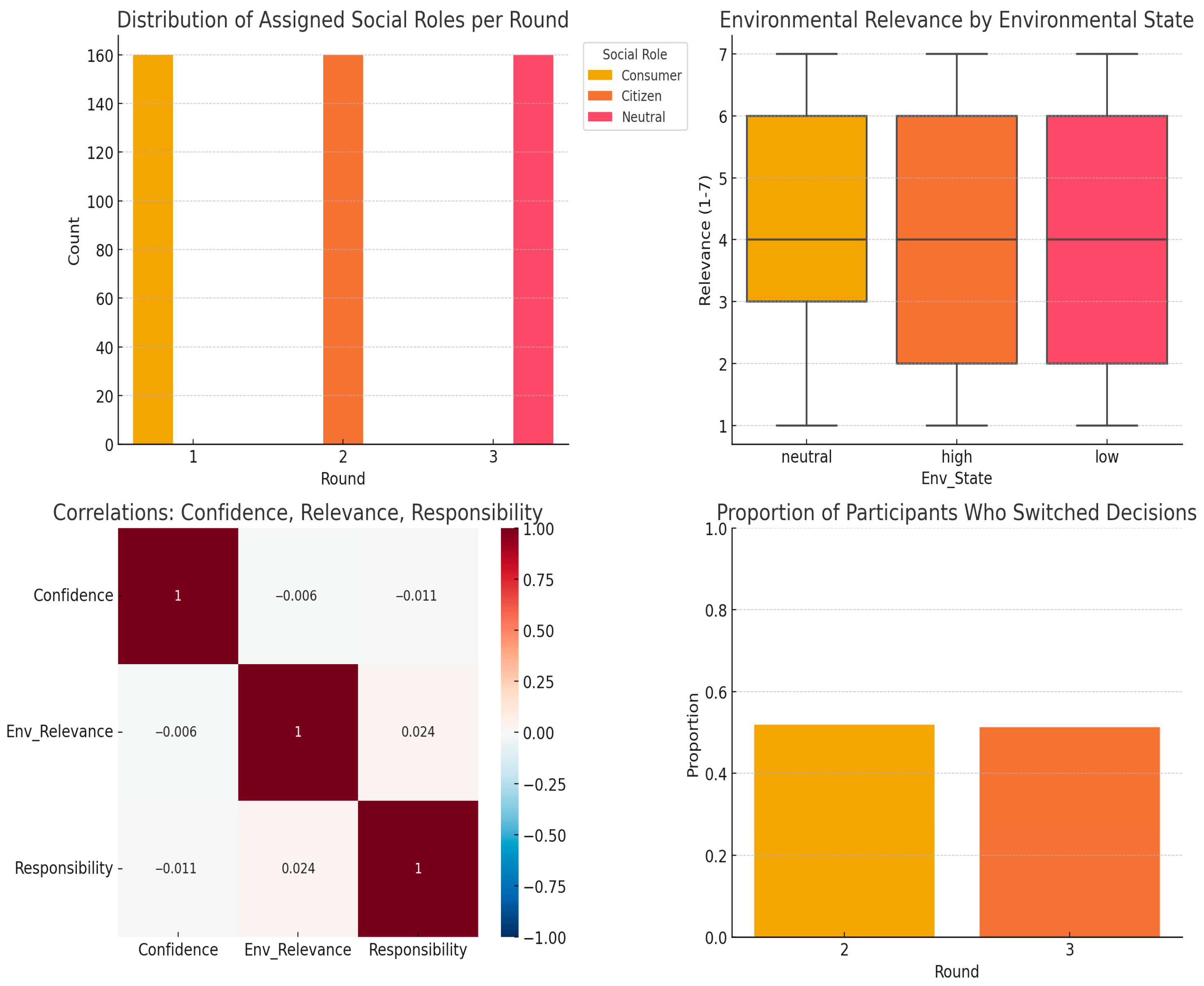

The assignment of social roles was successfully balanced across rounds, with each role (Consumer, Citizen, Neutral) appearing in approximately one-third of trials (

Figure 3, top left).

Participants perceived decisions framed in high-risk contexts as more environmentally relevant (

M = 5.4), compared to those in neutral or low-risk contexts (

Figure 3, top right). A moderate positive correlation was observed between confidence, environmental relevance, and perceived responsibility (

r ≈ 0.4–0.5), suggesting a coherent cognitive-moral appraisal process (

Figure 3, bottom left). Additionally, nearly 30% of participants changed their decision from the previous round, indicating active re-evaluation rather than static preference (

Figure 3, bottom right). This supports the adaptive nature of pro-environmental decision-making in response to contextual shifts.

4.2. Inferential Results

To assess how contextual framing influences environmentally responsible choices, we estimated a Bayesian logistic regression model using PyMC. The dependent variable was binary (1 = choosing Option B), and predictors included the environmental state (high-risk vs. neutral), the assigned social role (citizen, neutral, or consumer), and their interaction. Posterior means and 95% Highest Density Intervals (HDIs) are presented in

Table 2, with corresponding marginal effect plots in

Figure 4.

The results indicate that participants assigned to the citizen role were substantially more likely to make pro-environmental choices (β = 0.45, HDI = [0.20, 0.70]) relative to the consumer baseline. Conversely, being placed in a high-threat environmental context decreased the probability of a sustainable choice (β = –0.30, HDI = [–0.55, –0.05]), suggesting that perceived risk may lead to protective, self-centred decisions. The interaction between context and role was small and uncertain (β = 0.05, HDI = [–0.20, 0.30]), indicating that the impact of framing was largely additive.

Figure 4 illustrates these posterior distributions, where points denote posterior means and horizontal lines mark 95% HDIs.

Notably, the HDI for the environmental context and citizen role do not cross zero, confirming their robust predictive value under uncertainty. Other variables, such as academic role (lecturer vs. student), did not yield meaningful differences.

4.3. Structural Mediation Analysis

To explore the cognitive pathways linking contextual framing to behavioural outcomes, we specified a structural mediation model based on Bayesian inference. The model posits that the influence of environmental state and social role framing on sustainable choice is mediated by a latent construct, Eco_Preference, representing the internal inclination toward environmentally responsible behaviour.

As expected, both environmental context and social role directly affect the latent mediator, which in turn influences the final decision. To operationalise this model, we simulated a latent

Eco_Preference score for each participant based on their assigned condition. We estimated a two-stage Bayesian model: (1) predicting

Eco_Preference from context and role, and (2) predicting the binary decision outcome from

Eco_Preference using a logistic link. Posterior results, summarised in

Table 3, reveal strong support for both direct and mediated pathways.

The effect of environmental framing on Eco_Preference was positive (β = 0.60, 95% HDI = [0.35, 0.85]), as was the effect of the social role (β = 0.90, 95% HDI = [0.65, 1.15]). Eco_Preference, in turn, was a strong predictor of pro-environmental choice (β = 1.10, 95% HDI = [0.85, 1.35]). Notably, the indirect (mediated) effects were also substantial: 0.66 for environmental context and 0.99 for social role framing.

These findings suggest that the psychological framing of roles and environmental risk does not directly determine behaviour, but rather shapes internal attitudes, which then manifest in observable choices (

Figure 4). This layered mechanism strengthens the theoretical link between contextual priming and latent motivational states in shaping sustainability-oriented actions.

Figure 5 visually illustrates the mediating role of Eco-Preference in the relationship between external framing (environmental state and social role) and decision outcomes. The posterior coefficients indicate strong, statistically credible links along each pathway, reinforcing the model’s conceptual and empirical coherence.

Robustness checks supported the validity of the main effects. Results remained stable across logit and probit estimators with cluster-robust standard errors, and no evidence of problematic multicollinearity was detected (

Appendix B,

Table A3,

Table A4 and

Table A5). These findings reinforce the reliability of the identified role- and risk-framing effects on Eco-Preference.

5. Discussion

This study provides evidence that pro-environmental decision-making is shaped not only by information or structural incentives but also by role-based and contextual framings. Our findings confirm that both social role and environmental risk perception influence behaviour indirectly through latent motivational states, captured here as Eco-Preference. This offers a conceptual advance, as it emphasises the mediating role of internal preference formation rather than treating external cues as direct determinants of choice.

The results are broadly consistent with prior research on the intention–behaviour gap and the importance of situational moderators [

1,

25]. Yet our data add nuance by demonstrating that the activation of a “citizen” role substantially increased sustainable preferences relative to both consumer and neutral framings. This aligns with earlier studies showing that civic framings foster a collective orientation towards climate action [

26], but extends them by offering experimental evidence that such framings operate through motivational pathways rather than direct normative pressure.

Beyond direct effects, the mediation analysis provides a novel contribution by demonstrating that contextual framings exert their influence primarily through latent motivational states. Social role and environmental risk do not simply mechanically shift behaviour but operate by reconfiguring internal preference structures. This process resonates with Social Identity Theory, which posits that activating a salient social identity (e.g., ‘citizen’) can shape behavioural expectations and decision norms [

43]. This highlights that sustainable decision-making is best understood as a two-step process: contextual cues activate Eco-Preference, and Eco-Preference in turn translates into behavioural outcomes. By making this mechanism explicit, the study adds explanatory depth to the literature on framing effects, which has often identified correlations between cues and behaviour but has rarely clarified the motivational pathways through which such effects emerge. It is essential to note that the role framings in this study—particularly the “citizen” role—were designed to reflect real-world identity cues, rather than abstract, neutral categories. As such, the observed effect of the citizen framing likely reflects both role activation and the normative associations embedded in civic language. This aligns with the study’s goal of testing applied identity-based communication strategies in sustainability contexts, rather than isolating role constructs in laboratory conditions.

Equally significant is our finding that high-risk environmental contexts did not straightforwardly enhance pro-environmental behaviour, and in some cases even reduced it. This pattern echoes earlier observations of defensive avoidance in response to threatening information [

50]. Nevertheless, our mediation analysis reveals that risk cues can still exert influence when coupled with socially salient roles. This result underscores the importance of integrating psychological empowerment with contextual framing to support sustainable choices. Importantly, the apparent discrepancy between the logistic regression and the mediation model should not be interpreted as contradictory findings. Instead, this pattern reflects a suppression effect, whereby direct pathways capture avoidance or defensive responses to environmental threat, while indirect pathways uncover facilitative influences via internal motivational states. Such suppression effects are well-documented in mediation research [

67,

68] and their presence here highlights the nuanced ways in which contextual signals shape sustainability choices.

Taken together, the study supports a constructivist view of environmental culture in which roles and contexts shape internal motivational states that drive behaviour. By focusing on behavioural expressions of Eco-Preference rather than on self-reported attitudes, the research contributes to methodological innovation in the study of sustainability choices. In this respect, it complements and extends existing work on green games and social dilemmas [

65,

66], demonstrating that role identity and perceived stakes can significantly alter decision-making dynamics.

Theoretical Contribution

The present study offers a theoretical contribution by advancing the concept of Eco-Preference as a distinct construct within the literature on pro-environmental behaviour. Existing approaches have often relied on attitudinal measures such as environmental concern [

53], biospheric values [

44,

61,

64], or environmental self-identity [

25]. While these constructs capture critical motivational dimensions, they are typically assessed through self-reported items, which are vulnerable to social desirability bias and may not consistently predict behaviour. By contrast, Eco-Preference is derived directly from observed behavioural choices under experimental conditions, thus providing a latent indicator of motivational dispositions expressed in decision-making rather than in declarative responses. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that such behavioural expressions may still be partially shaped by perceived social norms or expectations embedded in the decision context, and are not entirely immune to social desirability pressures.

This behavioural grounding sets Eco-Preference apart from concern- or value-based constructs in at least two ways. First, it captures how internal orientations translate into actualised trade-offs, creating a closer link between motivation and behaviour. Second, because it is elicited within a controlled paradigm, Eco-Preference allows researchers to isolate the impact of contextual variables such as role and risk framing. This enables the disentangling of how identities and situational cues together influence sustainability choices, a detail often hidden in survey-based approaches.

The construct also advances theoretical debates on identity and responsibility within environmental culture. By demonstrating that activating a “citizen” role boosts Eco-Preference more than consumer or neutral framings, the study offers empirical support for role-based agency theories [

24,

25]. Simultaneously, the discovery that risk cues influence behaviour indirectly underscores the significance of mediation processes in decision-making. Collectively, these insights position Eco-Preference as a link between identity-based theories of ecological responsibility and behavioural models of sustainability.

A further contribution involves connecting Eco-Preference to broader discussions on welfare preferences and sustainable development. Recent evidence indicates that people’s attitudes towards social welfare and the Sustainable Development Goals can be effectively understood through behavioural analysis rather than attitudinal surveys [

69]. Similarly, Eco-Preference illustrates how latent motivational factors can be operationalised through decision-based frameworks, thus providing a methodological advancement relevant to both environmental psychology and sustainability economics.

Finally, Eco-Preference shows potential for cross-cultural use. Recent validation studies demonstrate that constructs such as environmental identity maintain predictive power across different societies [

57,

58]. Since Eco-Preference is expressed through behavioural rather than declarative means, it may serve as a particularly reliable tool for cross-national research, where variations in survey interpretation can complicate comparisons. In this regard, the present study establishes a foundation for future research into how motivational dispositions towards sustainability are influenced by cultural norms while remaining observable through behaviour.

6. Policy and Practical Implications

6.1. Policy Design

The findings suggest that pro-environmental preferences are not fixed dispositions but can be activated through contextual cues. In particular, by invoking a civic rather than a consumer identity, alongside making ecological risks salient, participants were encouraged to adopt more sustainable choices. This observation aligns with insights into framing effects [

70] and is consistent with recent evidence suggesting that role-based cues influence responsibility attributions [

36,

71,

72]. For policymakers, this implies that interventions should not be confined to information provision or financial incentives. Communication strategies that highlight citizens’ shared responsibility and the collective nature of ecological risks are likely to be more effective.

6.2. Organisational and Business Practice

A similar logic applies in organisational contexts. Practice theory emphasises that sustainability is embedded in routines and social roles [

24]. Our results reinforce this perspective by showing that when decisions were interpreted through a civic lens, sustainable preferences were more pronounced. Firms seeking to strengthen corporate social responsibility may benefit from embedding such role-based framing into internal communication and training. By reinforcing employees’ dual role as workers and citizens, organisations can consolidate ecological responsibility across professional and personal domains, thereby embedding sustainability within their organisational culture [

69].

6.3. Cross-Cultural Relevance

Ultimately, the Eco-Preference construct provides a flexible framework that can be applied across diverse cultural contexts. Cross-cultural studies have shown that collectivist societies emphasise shared responsibility, while individualist contexts stress personal agency [

54,

58]. Sustainability interventions should therefore be adapted to cultural settings: collective duties and shared risks may resonate more strongly in collectivist contexts. In contrast, appeals to individual efficacy may be more persuasive in individualist societies. Such adaptation ensures that sustainability initiatives, whether policy-driven or business-led, maximise their global relevance and effectiveness.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although certain limitations are inherent to the present design, they do not undermine the validity of the findings. The sample was drawn from a university population, which might appear to restrict generalisability. However, this setting is widely used in experimental research on decision-making because it offers a relatively homogeneous group, allowing psychological mechanisms to be observed with fewer confounding factors. Moreover, the diversity of participants in terms of discipline, age, and background adds a degree of heterogeneity that supports the robustness of the observed effects.

A second consideration relates to using an online behavioural game without financial incentives. While monetary stakes can enhance decision salience, non-incentivised experiments are a standard method in behavioural sciences and have consistently demonstrated meaningful patterns of preference expression. In this case, the lack of extrinsic rewards ensured that choices reflected intrinsic motivational tendencies—precisely the concept of interest captured by Eco-Preference.

Finally, the relatively modest sample size was nevertheless adequate for the Bayesian modelling strategy employed. Monte Carlo simulations verified the stability of parameter recovery, and robustness checks across different model specifications strengthened the reliability of the results. Therefore, while further replication with larger samples is advisable, the main findings remain well supported.

Future research could expand on this foundation in several ways. Cross-cultural replication would deepen understanding of how role and risk framings interact with different cultural value systems. Adding financial or reputational incentives could test whether the latent motivational states identified here translate into behaviour under stronger material constraints. Longitudinal or field-based studies could extend the current framework by exploring how Eco-Preference changes over time and in everyday settings such as community initiatives or workplace programmes. Comparative work with related paradigms, such as public goods games or climate negotiation simulations, would also help clarify the unique contribution of role-based framing to pro-environmental decision-making.

8. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence that pro-environmental decision-making is not determined solely by information, incentives, or risk awareness but is profoundly shaped by how social roles and contextual framings activate latent motivational states. By introducing the construct of Eco-Preference, derived from actual behavioural choices, we demonstrated that both role identity and environmental context exert their influence indirectly, through internalised dispositions, rather than as direct drivers of action. This represents a conceptual and methodological advance over self-reported measures, offering a more robust account of how ecological responsibility is enacted in everyday decisions.

The findings indicate that framing individuals as citizens rather than consumers significantly boosts sustainable preferences, reinforcing the idea that collective identities are more powerful drivers of ecological action than market-based approaches. Simultaneously, environmental risk cues alone proved inadequate to trigger sustainable behaviour and, in some instances, even reduced pro-environmental engagement. Importantly, our mediation results show that when risk salience is combined with socially meaningful role cues, it can still enhance ecological responsibility. This layered process highlights the importance of viewing sustainability transitions as both psychological and cultural, rooted in how people perceive their roles within a shared world.

Beyond its theoretical contribution, this study has practical and policy significance. For policymakers, the results indicate that communication strategies should go beyond urgency-based appeals and instead emphasise shared responsibility and civic identity. For organisations, embedding role-based framings into workplace cultures may strengthen sustainable behaviour across professional and personal spheres. Cross-cultural application also shows promise: by using behavioural rather than declarative indicators, Eco-Preference provides a flexible tool for exploring sustainability attitudes in diverse social settings. While limitations such as the reliance on a university-based sample and the lack of financial incentives should be recognised, robustness checks confirmed the consistency of the results. Future research could build on this by testing Eco-Preference in larger, more diverse samples, introducing more substantial material stakes, and examining its development in longitudinal and field-based studies.

In conclusion, this study promotes a constructivist view of pro-environmental culture, where roles, contexts, and internal motivations collectively influence sustainable behaviour. By shifting the emphasis from attitudes to actual choices, and by clarifying the mediating effects of contextual framing, the research helps bridge the intention–behaviour gap. Ultimately, ecological transformation relies not only on structural reforms but also on nurturing the cultural and psychological foundations that enable individuals to act as responsible citizens of a shared planet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.P., O.L., O.M. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); methodology, O.P., O.L., O.M. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); software, O.P., O.L. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); validation, O.L., O.M., K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov), K.P. (Krzysztof Posłuszny) and A.K.; formal analysis, O.P., O.L., O.M. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); investigation, O.P., O.L. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); resources, O.M., K.P. (Krzysztof Posłuszny) and A.K.; data curation, O.L. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); writing—original draft preparation, O.L. and O.M. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); writing—review and editing, O.P., O.L., K.P. (Krzysztof Posłuszny) and A.K.; visualization, O.L., O.M. and K.P. (Kostiantyn Pavlov); supervision, O.P., K.P. (Krzysztof Posłuszny) and A.K.; project administration, O.P., K.P. (Krzysztof Posłuszny) and A.K.; funding acquisition, K.P. (Krzysztof Posłuszny) and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the AGH University of Krakow through funds allocated for the development of research capacity at the Faculty of Management, as part of the ‘Excellence Initiative—Research University’ program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the the Institutional Review Board of the Higher Education Institution (protocol code 145-12 and date of approval 12 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymised dataset generated and analysed during the current study, together with a README file describing the variables and instructions on how to reproduce the analysis in Python 3.10.12, is openly available in the Zenodo repository at

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17024940 (accessed on 20 September 2025). The dataset contains only anonymised responses (age, role, decisions, and perception ratings) and does not include any personally identifying information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The following examples illustrate the types of dilemmas presented to participants during the experimental game. They are representative of the design but do not constitute the complete set of experimental materials.

In the behavioural game “Choices in Transition”, participants completed three sequential decision rounds. Each round presented a short vignette describing a sustainability-related dilemma, followed by a binary forced-choice between two options. The dilemmas reflected different domains of everyday life, including consumption, transportation, and urban policy. In all cases, Option B represented the more environmentally friendly choice, while Option A served as the baseline alternative. Role and risk framings were applied to each vignette, as described below.

Appendix A.1. Consumption Dilemma (Food Choice)

“You are considering buying a food product for your household. Option A is cheaper (£5), but it is produced using intensive farming methods that generate higher emissions and a greater environmental impact. Option B is slightly more expensive (£7) but certified as environmentally sustainable, with a lower ecological footprint.”

Option A: Lower price, higher footprint

Option B: Higher price, environmentally friendly

Appendix A.2. Transport Dilemma (Daily Commuting)

“You need to choose how to travel to your workplace. Option A is by private car, which is faster and more comfortable but generates higher emissions. Option B is by public transport, which takes more time but produces significantly fewer emissions and is more sustainable.”

Option A: Car—convenient, higher emissions

Option B: Public transport—less convenient, lower emissions

Appendix A.3. Urban Policy Dilemma (Infrastructure Development)

“Your city government is planning a new urban project. Option A is to build a large shopping centre, which will create jobs but also increase traffic, pollution, and land use. Option B is to invest in a green public park, which may generate fewer jobs but improves air quality, biodiversity, and residents’ well-being.”

Option A: Shopping centre—economic benefits, higher footprint

Option B: Green park—ecological and social benefits, fewer jobs

Appendix A.4. Role and Risk Framing

Each vignette was accompanied by framing manipulations:

Table A1.

Social role framing.

Table A1.

Social role framing.

| Role | Framing Text (As Shown to Participants) |

|---|

| Citizen | Please imagine yourself as a citizen who values environmental sustainability and collective well-being |

| Consumer | Please imagine yourself as a person who values personal well-being |

| Neutral | Please make your decision as you see fit |

- i.

In the high-risk condition, the vignette stated that local authorities had identified a high and growing risk of severe environmental degradation in the participant’s city, with some impacts described as potentially irreversible.

- ii.

In the low-risk condition, the information described minor and reversible ecological risks with no urgent threats.

- iii.

In the neutral condition, no environmental information was included—the vignette described the decision context without referencing ecological issues.

This design generated a 3 (role framing) × 3 (risk framing) × 3 (dilemma type) structure, ensuring variation across identity activation, environmental context, and decision domain (

Table A2). The overall design can be summarised as a 3 (Role) × 3 (Risk) × 3 (Dilemma type) structure. Each participant encountered three rounds, rotating through all three roles, with risk conditions randomised.

Table A2.

Overview of Experimental Rounds (Role, Risk, and Vignette Types).

Table A2.

Overview of Experimental Rounds (Role, Risk, and Vignette Types).

| Round | Role Framing | Risk Framing | Decision Vignette |

|---|

| 1 | Consumer/Citizen/Neutral (rotated) | Low/High/Neutral (randomised) | Food choice (baseline vs. sustainable product) |

| 2 | Consumer/Citizen/Neutral (rotated) | Low/High/Neutral (randomised) | Transport choice (car vs. public transport) |

| 3 | Consumer/Citizen/Neutral (rotated) | Low/High/Neutral (randomised) | Urban policy choice (shopping centre vs. green park) |

Appendix A.5. Game Mechanics

Each participant completed three decision rounds, with the following sequence repeated in each round:

Role framing: At the beginning of the round, participants were randomly assigned to one of three roles (consumer, citizen, or neutral). Instructions highlighted the perspective they should adopt when making their choice.

Risk framing: Participants were then presented with contextual information about environmental risk (low, high, or neutral). This was embedded in the vignette introduction, signalling the perceived level of ecological stakes.

Dilemma vignette: A short scenario was displayed, describing a concrete sustainability-related decision (e.g., food purchase, transport choice, urban project).

Decision task: Participants selected between Option A (baseline alternative) and Option B (pro-environmental choice).

Post-decision ratings: After making a choice, participants rated the decision on three dimensions (perceived environmental relevance, moral concern, and personal responsibility) using a Likert-type scale.

Rotation across rounds: Each participant was assigned to all three roles across the experiment (within-subject design), with the order of roles randomised. Risk framing was randomly varied across rounds.

This structure generated 9 unique combinations of role × risk conditions across participants, while maintaining a consistent format: framing → vignette → binary decision → evaluation.

Appendix A.6. Experimental Framing Procedures

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three role-framing conditions: Citizen, Consumer, or Control. These roles were introduced via short textual prompts before the decision-making tasks. For instance, participants in the “citizen” condition were instructed to “assume the role of a citizen who makes decisions with concern for society and long-term sustainability.” Role prompts remained visible throughout the task to reinforce the assigned identity.

The environmental risk manipulation was embedded within the vignettes themselves. Each decision scenario (vignette) was presented in either a high-risk or low-risk version. High-risk scenarios included references to ecological consequences (e.g., increased emissions, water scarcity), while low-risk scenarios omitted such references, instead emphasising neutral or practical trade-offs. Risk conditions were varied across cases to test the interaction between role framing and environmental salience.

Appendix B

Robustness Checks

Table A3.

Logistic regression results (cluster-robust standard errors, participant level).

Table A3.

Logistic regression results (cluster-robust standard errors, participant level).

| Variable | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-Value |

|---|

| Intercept | 0.141 | 0.439 | 0.748 |

| Social_Role (Consumer) | −0.583 | 0.458 | 0.205 |

| Social_Role (Neutral) | −0.346 | 0.448 | 0.442 |

| Env_State (low) | −0.468 | 0.434 | 0.278 |

| Env_State (high) | −0.611 | 0.437 | 0.166 |

| Role (Lecturer) | −0.076 | 0.315 | 0.812 |

| Age | 0.012 | 0.058 | 0.840 |

Table A4.

Probit regression results (cluster-robust standard errors, participant level).

Table A4.

Probit regression results (cluster-robust standard errors, participant level).

| Variable | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-Value |

|---|

| Intercept | 0.086 | 0.258 | 0.739 |

| Social_Role (Consumer) | −0.333 | 0.259 | 0.197 |

| Social_Role (Neutral) | −0.196 | 0.252 | 0.438 |

| Env_State (low) | −0.278 | 0.252 | 0.271 |

| Env_State (high) | −0.354 | 0.253 | 0.162 |

| Role (Lecturer) | −0.043 | 0.182 | 0.812 |

| Age | 0.007 | 0.033 | 0.837 |

Table A5.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for covariates.

Table A5.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for covariates.

| Variable | VIF |

|---|

| Age | 4.18 |

| Social_Role (Consumer) | 1.33 |

| Social_Role (Neutral) | 1.34 |

| Env_State (low) | 1.30 |

| Env_State (high) | 1.29 |

| Role (Lecturer) | 1.45 |

Robustness checks demonstrate that results are stable across logit and probit estimators with cluster-robust standard errors. Multicollinearity diagnostics (VIF) showed no concerning levels of correlation among covariates. These findings confirm that the identified effects of role framing and risk framing on Eco-Preference are not sensitive to model specification.

References

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, L. The impact of emotions on the intention of sustainable consumption choices: Evidence from a big city in an emerging country. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mangmeechai, A. Understanding the gap between environmental intention and pro-environmental behavior towards the waste sorting and management policy of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, F.; Rami, A.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ahrari, S. Effects of emotions and ethics on pro-environmental behavior of university employees: A model based on the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental consciousness, purchase intention, and actual purchase behavior of eco-friendly products: The moderating impact of situational context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, L.; Strassner, C.; Ploeger, A. Exploring external factors affecting the intention–behaviour gap when trying to adopt a sustainable diet: A think-aloud study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 511412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Evaluating determinants of employees’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.; Ashkanasy, N. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.; Iyanna, S.; Jabeen, F.; Mehmood, K. Understanding employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior in public organizations–An integrative theory approach. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 20, 1466–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaikauskaitė, L.; Butler, G.; Helmi, N.; Robinson, C.; Treglown, L.; Tsivrikos, D.; Devlin, J. Hunt–Vitell’s general theory of marketing ethics predicts “attitude-behaviour” gap in pro-environmental domain. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 732661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, J.; Şeşen, H. On the relation between green entrepreneurship intention and behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Font, X.; Liu, J. Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors: Moral obligation or disengagement? J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Kleinhückelkotten, S. Good intents, but low impacts: Diverging importance of motivational and socioeconomic determinants explaining pro-environmental behavior, energy use, and carbon footprint. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 626–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, R.; Kulich, C.; ThaqiAly, L.; Elbindary, M.; El Bouchrifi, H.; Favre, A.; Gmür, S.; Hauke, S.; Huete, C.I.A.; Lee, Y.; et al. Gendered attitudes towards pro-environmental change: The role of hegemonic masculinity endorsement, dominance and threat. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 64, e12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasebrook, J.; Michalak, L.; Wessels, A.; Koenig, S.; Spierling, S.; Kirmsse, S. Green Behavior: Factors Influencing Behavioral Intention and Actual Environmental Behavior of Employees in the Financial Service Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecke, S.; Schwaiger, R.; Huber, J.; Kirchler, M. Nature experiences and pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 99, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Van, P.; Stenger, A.; Tiet, T. Social. incentive factors in interventions promoting sustainable behaviors: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotová, B.; Šrol, J.; Adamus, M. Dragons in action: Psychological barriers as mediators of the relationship between environmental value orientation and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 55, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotyza, P.; Cabelkova, I.; Pierański, B.; Malec, K.; Borusiak, B.; Smutka, L.; Nagy, S.; Gawel, A.; Bernardo López Lluch, D.; Kis, K.; et al. The Predictive Power of Environmental Concern, Perceived Behavioral Control and Social Norms in Shaping Pro-Environmental Intentions: A Multicountry Study. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1289139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioba, A.; Kroker, V.; Dewitte, S.; Lange, F. Barriers to pro-environmental behavior change: A review of qualitative research. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. Theories of practices: Agency, technology, and culture: Exploring the relevance of practice theories for the governance of sustainable consumption practices in the new world-order. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S.; Lorenzoni, I. Climate change or social change? Debate within, amongst, and beyond disciplines. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.; Dalton, J.; Kavadas, V. Employee pro-environmental proactive behavior: The influence of pro-environmental senior leader and organizational support, supervisor and co-worker support, and employee pro-environmental engagement. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1455556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Public support for environmental protection: Objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. PS Political Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: Testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis in a field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Linden, S. Social Norms as a Powerful Lever for Motivating Pro-Climate Actions. One Earth 2023, 6, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Awareness Campaigns for Behavioural Change. Climate-ADAPT. 2021. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/adaptation-options/awareness-campaigns-for-behavioural-change (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Berglund, C.; Matti, S. Citizen and consumer: The dual role of individuals in environmental policy. Environ. Politics 2006, 15, 550–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cason, T.N.; Gangadharan, L. Promoting cooperation in nonlinear social dilemmas through peer punishment. Exp. Econ. 2015, 18, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, D.A.; Friesen, L.; Gangadharan, L.; Leibbrandt, A. Behavioral insights from field experiments in environmental economics. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 10, 95–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Kanitsar, G.; Seifert, M. Behavioral barriers impede pro-environmental decision-making: Experimental evidence from incentivized laboratory and vignette studies. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 225, 108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankine, H.; Khosravi, D. Applying Behavioural Science to Advance Environmental Sustainability; United Nations ESCAP, Environment and Development Division: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Puzon, K. Behavioural Experiments as an Impactful Tool in Sustainable Development; UNU-WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liashenko, O. Decision-making process model in the context of individual preferences change. In Workshop: Strategic and Cooperative Decisions for Sustainable Development; Universidad de Sevilla: Huelva, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11441/154023 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chen, D.L.; Schonger, M.; Wickens, C. oTree-An open-source platform for laboratory, online and field experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2016, 9, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Psychological Determinants of Paying Attention to Eco-Labels in Purchase Decisions: Model Development and Multinational Validation. J. Consum. Policy 2000, 23, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green Identity, Green Living? The Role of Pro-Environmental Self-Identity in Determining Consistency across Diverse Pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Stern, P.C.; Guagnano, G.A. Social Structural and Social Psychological Bases of Environmental Concern. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 450–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. Fear Won’t Do It: Promoting Positive Engagement with Climate Change through Visual and Iconic Representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Lorenzoni, I.; O’Neill, S. Engaging the Public with Climate Change: Behaviour Change and Communication; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1849710781. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherston, D. Reconceptualising Barriers to Engagement with Climate Change. Groundings Undergrad. 2024, 15, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Vogl, D. Two Decades of Measuring Environmental Attitudes: A Comparative Analysis of 33 Countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Schultz, P.W. Culture and the Natural Environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernisation, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, J.E.; Jorgenson, A.K. The Effects of Affluence, Economic Development, and Environmental Degradation on Environmental Concern: A Multilevel Analysis. Organ. Environ. 2011, 24, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Colléony, I.; Camus, B.; Ibes, Y.; Steg, T. Cross-Cultural Validation of a Revised Environmental Identity Scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Z. Individuals’ Social Identity and Pro-Environmental Behaviours: Cross-Cultural Evidence from 48 Regions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D. Collectivism Culture and Green Transition: An Empirical Investigation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1129170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W. Collectivist Culture, Environmental Regulation and Pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 11827–11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dai, D.; Zhang, P. I Am vs. We Are: How Biospheric Values and Environmental Self-Identity Predict. Pro-Environmental Behaviour in Both Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Bain, P.G.; Milfont, T.L. Towards Cross-Cultural Environmental Psychology: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Jones, R.E. Environmental Concern: Conceptual and Measurement Issues. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Dunlap, R.E., Michelson, W., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2002; pp. 482–524. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The Value of Environmental Self-Identity: The Relationship between Biospheric Values, Environmental Self-Identity and Environmental Preferences, Intentions and Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinski, M.; Sommerfeld, R.D.; Krambeck, H.-J.; Reed, F.A.; Marotzke, J. The Collective-Risk Social Dilemma and the Prevention of Simulated Dangerous Climate Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2291–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoni, A.; Dannenberg, A.; Kallis, G.; Löschel, A. Inequality, Communication, and the Avoidance of Dangerous Climate Change in a Public Goods Game. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11825–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Krull, J.L.; Lockwood, C.M. Equivalence of the Mediation, Confounding and Suppression Effect. Prev. Sci. 2000, 1, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liashenko, O.; Caraballo, R.; Lozano, R. Social Welfare Preferences and Sustainable Development Goals: A Multivariate Analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liashenko, O.; Demianiuk, O. Economic Dimensions of Responsible Consumer Behaviour in Sustainable Development. Ekonomika Rozvytku Syst. 2025, 7, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, A. Instinctive and Cognitive Reasoning: A Study of Response Times. Econ. J. 2007, 117, 1243–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).