5.1. Benchmark Regression

Table 4 presents the baseline regression results examining the relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs. Whether control variables or fixed effects are included, the estimated coefficient of GF is significantly positive at the 1% level, supporting Hypothesis H1 that GF is positively correlated with corporate NQPFs. In the specification that includes industry, year, and city fixed effects, all control variables, and cluster standard errors at the city–year level (Column 4), the coefficient for GF is 1.3655. This indicates that a one-unit increase in the city-level GF index is associated with an average increase of approximately 1.37 units in corporate NQPFs. This finding suggests that GF provides robust financial support for corporate green innovation and quality–efficiency enhancement, incentivizing firms to increase R&D investment, adopt more energy-efficient production technologies, attract and cultivate high-quality talent, and promote the development of strategic emerging industries and future-oriented sectors [

62], thereby injecting strong momentum into the cultivation and development of corporate NQPFs.

The regression results for the control variables offer additional insights into the organizational and governance factors influencing corporate NQPFs. Specifically, a higher proportion of independent directors (Ind) is positively associated with NQPFs, suggesting that board independence enhances oversight and strategic guidance, thereby facilitating resource allocation toward innovation and productivity-enhancing activities. Similarly, longer firm age (Age) correlates positively with NQPFs, likely reflecting accumulated experience, established routines, and greater access to resources that support sustained productivity growth. In contrast, a higher cash ratio (Cash) exhibits a negative relationship with NQPFs, which may indicate risk-averse financial management that prioritizes liquidity over strategic investments in green technologies or structural upgrades. Furthermore, the negative association between return on assets (Roas) and NQPFs implies that firms with strong short-term profitability may lack the impetus to pursue disruptive innovation and structural transformation, potentially due to satisfaction with existing business models or path dependence, thereby hindering the cultivation of long-term-oriented new quality productivity.

5.2. Robustness Analysis

Firstly, this study conducts a robustness test by using the alternative explained and explanatory variable. Because both corporate NQPFs and TFP are important indicators for measuring production efficiency, this paper uses TFP as the alternative explained variable. In terms of measurement method, the OP method overcomes simultaneity bias in production function estimation by using firm investment as a proxy for unobserved productivity shocks, while the LP method instead uses intermediate inputs as a proxy, which applies more broadly to firms with zero investment periods. At the same time, the paper considers that finance can extend its service terminals through information networks and has the characteristics of cross-regional services. This paper uses provincial green credit (measured by the proportion of interest expenses in the six major high-energy-consuming industries, with data sourced from the China Industrial Statistical Yearbook) as the explanatory variable to measure the level of regional GF development [

63]. In addition, this paper also uses principal component analysis to re-measure GF.

Table 5 presents the regression results for corporate TFP using the OP and LP methods in columns (1) and (2), respectively. Columns (3) and (4) report the regression results using provincial green credit and an alternative measure of GF, respectively. It is observed that the estimated coefficient of GF exerts a statistically significant positive effect on TFP at the 1% level. Moreover, the coefficient of GF measured by the negative indicator (Gcred) is significantly negative at the 1% level, while that of the alternative GF measure (GF2) is significantly positive; both indicate a positive relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs. These results robustly confirm the findings of our baseline regression.

Secondly, this study conducts three robustness tests. The first test considers the severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by deleting samples from the 2020–2022 period. The second test excludes the five provinces and eight areas (the specific areas of the first batch of green finance reform and innovation pilot zones are Huzhou City and Quzhou City in Zhejiang Province, Guian New District in Guizhou Province, Hami City, Changji Prefecture, and Karamay City in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Guangzhou City in Guangdong Province, and Ganjiang New District in Jiangxi Province) designated as the first batch of GF reform and innovation pilot zones in 2017. The third test excludes financial center cities: specifically, based on the authoritative China Financial Center Index (CFCI), we identified and removed all 31 cities classified as national or regional financial centers (including those in the northeast, northern coastal, eastern coastal, southern coastal, central, and western regions). These robustness tests aim to mitigate potential inaccuracies caused by abnormal years (2020–2022), sample enterprises in policy pilot zones, and the unique characteristics of major financial hubs.

Table 6 presents the results. We observed that the GF coefficients remain positive and statistically significant across all specifications. This confirms that the positive relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs is robust and not driven by these special samples, thereby strengthening the generalizability of our findings.

Thirdly, to mitigate possible endogeneity issues arising from omitted variable bias and sample selection, this study employs the lagged one-period values of the explanatory variables as instrumental variables for the endogeneity test [

64]. The results of the two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression are presented in

Table 7. Columns (1) and (2) report the first-stage and second-stage results using the one-period lagged value of GF (L1.GF) as the instrument, while Columns (3) and (4) present the results using its two-period lagged value (L2.GF).

In the first stage, the coefficients on the instrumental variables are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating a strong positive correlation between the instrument and the endogenous variable GF. The Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistics (7800.432 and 6935.694) are significant at the 1% level, rejecting the null hypothesis of under-identification and confirming the relevance of the instruments. Furthermore, the exceptionally high Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F statistics (300,000 and 230,000) far exceed the critical value of 16.38, providing robust evidence against the weak instrument problem.

In the second stage, the estimated coefficients of GF remain positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that GF has a significant promoting effect on corporate NQPFs after controlling for endogeneity. The consistency of these results with our baseline findings reinforces the conclusion that the positive impact of GF on corporate NQPFs is causal and not driven by endogenous selection.

Lastly, this study uses the double difference method to further investigate the causal effect of the establishment of green financial reform and innovation pilot zone (2017) on corporate NQPFs. As shown in

Table 8, the coefficient of the core explanatory variable DID (treat × post) is significantly positive at the 1% level, whether the control variables are included or not, indicating that the establishment of the pilot area has significantly promoted the corporate NQPFs, and hypothesis 1 has been verified.

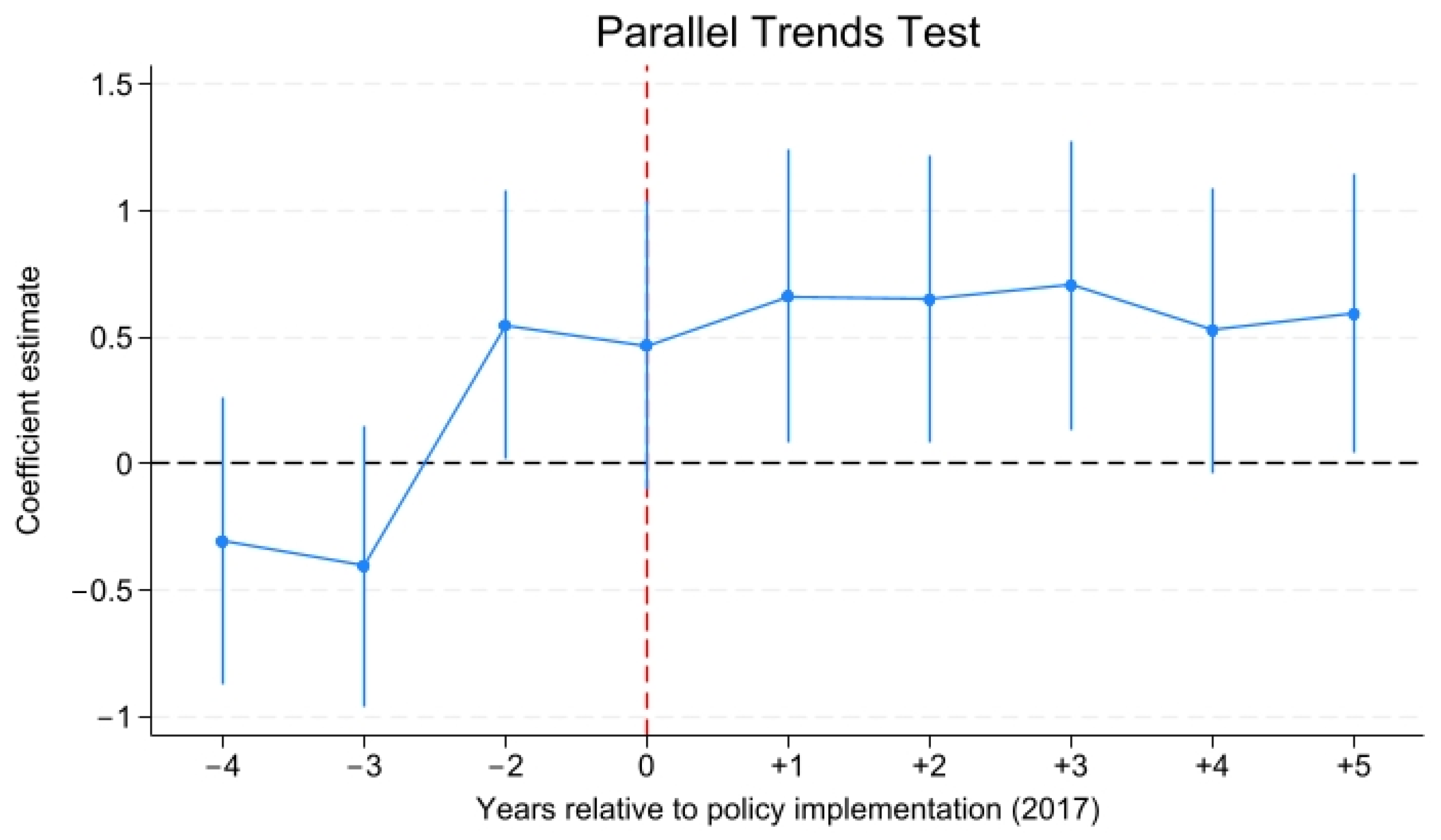

In order to test the parallel trend hypothesis, this paper further uses the event study method to verify it. The year before the implementation of the policy is taken as the benchmark period. The results of parallel trend test are shown in

Figure 2. There is no significant difference between the estimated coefficients of dummy variables in each period before the implementation of the policy and 0, indicating that the experimental group and the control group met the conditions of parallel trend before the policy impact.

Further analysis of the dynamic effect of the policy found that the impact of the establishment of the GF pilot zone on corporate NQPFs was mainly short-term. After the implementation of the policy, it increased slightly and was statistically significantly different from 0, but after the fourth year, the effect gradually weakened and returned to the non-significant level. This dynamic change may be due to the strong signal release and demonstration effect at the initial stage of the policy, which quickly stimulated the innovation willingness of enterprises. However, over time, the marginal decline in the efficiency of policy implementation, the failure of supporting measures to follow up in time, the “green floating” behavior caused by some enterprises’ strategic response, and the dilution effect of market competition on innovation funds may have jointly weakened the continuous incentive force of the policy.

5.3. Mechanism Analysis

5.3.1. Financing Constraint

Based on the theoretical analysis, it is evident that corporate financing constraints are influenced by the degree of green credit restrictions and the nature of property rights. We match the industry classification of listed companies with the environmental and social risk types (A, B, C) outlined in the “Key Evaluation Indicators for the Implementation of Green Credit” (industries included in Class A companies encompass nuclear power generation, hydropower generation, water conservancy and river port engineering construction, coal mining and washing, oil and natural gas extraction, ferrous metal ore mining and dressing, non-ferrous metal ore mining and dressing, non-metallic mineral mining and dressing, and other mining industries, which totals up to nine sectors; Class B companies are involved in industries such as oil processing, pharmaceutical manufacturing, railway transportation, rubber and plastic products, and pipeline transportation, comprising 25 industries; companies not classified as A or B are identified as Class C companies), where Class A and B companies are considered the green credit high-restricted group, and Class C is considered as the general-restricted group. Furthermore, the sample is also divided into state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises based on the nature of the property rights.

Table 9 presents the results. The coefficients in Columns (2) and (3) are significantly positive at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively, while the coefficients in Columns (1) and (4) are not statistically significant. These findings indicate that the positive impact of GF on corporate NQPFs is more pronounced for firms with lower financing constraints and for state-owned enterprises. Column (5) reports the regression results examining the moderating effect of the SA index, which measures the level of financing constraints based on the full sample of firms using Model (7). We observe that the estimated coefficient of SA and the interaction term between GF and SA are significantly positive at the 1% levels, respectively. Given that SA is a negative indicator (where larger, less negative values indicate milder constraints), the significantly positive coefficient of the interaction term suggests that financing constraints positively moderate the relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs. Specifically, for enterprises facing less severe financing constraints (i.e., those with larger SA values), GF exhibits a stronger promoting effect on corporate NQPFs.

These results demonstrate that alleviating financing constraints can enhance the positive relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs, thereby confirming Hypothesis H2. Furthermore, the significance of the Chow test (in the context of panel regression analysis, the Chow test is employed to examine whether there are significant differences in model parameters across different groups) indicates that higher environmental and social risks faced by firms are associated with stronger financing constraints, which impedes the cultivation of corporate NQPFs. Concurrently, the statistically insignificant coefficient of GF in Column (4) reveals the challenges faced by non-state-owned enterprises during the green transition. Influenced by their industrial attributes, non-state-owned enterprises are often smaller in scale. Due to a comparative lack of stable collateral, established credit histories, and implicit government guarantees, many non-state-owned enterprises are unable to translate policy incentives into innovation momentum as effectively or efficiently as their state-owned counterparts. Therefore, achieving the green transformation of non-state-owned enterprises requires more tailored supportive policies rather than relying solely on conventional credit constraints or incentives.

5.3.2. Environmental Law Enforcement

The intensity of government environmental enforcement is primarily influenced by the focus of the local government on environmental protection. Therefore, we have statistically analyzed the proportion of the frequency of words related to environmental protection in local government work reports, using it as an indicator to measure government attention to the environment. The sample companies are divided into two groups, high government attention and low government attention, based on the median, and the base model is estimated separately for each group.

Table 10 shows that the regression coefficients for GF are significantly positive in Column (1). It shows that the government’s environmental attention will promote the positive relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs. Furthermore, after introducing the interaction term of Punish and GF, it can be seen that the coefficient of the interaction term is −0.4294, and it has passed the significance test at the 1% level, indicating that there is a non-synergistic relationship between GF and Punish in influencing corporate NQPFs. Thus, Hypothesis H3 is supported.

Specifically, the government and the market often regulate the operation of the market economy through the “visible hand” and the “invisible hand”. Although Punish and GF have positive impacts on corporate NQPFs at different stages or aspects, their impact on corporate NQPFs is not a simple addition; instead, there is a certain degree of offset or weakening. As a deterrent governance tool, environmental administrative punishment may urge enterprises’ compliance when acting alone, but its joint implementation with GF shows a non-synergistic effect, which means that the compliance cost and operating pressure brought by punishment may crowd out the resources and energy of enterprises for long-term innovation. Enterprises are more inclined to adopt evasive strategies to avoid risks, rather than use funds for technological innovation and efficiency improvement, thus weakening the incentive effect of GF on corporate NQPFs.

5.3.3. Social Responsibility

We conduct a mechanism test on two major factors that affect corporate social responsibility: the public’s environmental concern and the scale of the enterprise. Following the literature [

65], we use the Baidu Index of residents’ searches for the keywords “environmental pollution” and “smog” to reflect the public’s environmental concern indicator for listed companies. Additionally, we use the enterprise’s operating income as a measure of the scale of the enterprise, dividing companies into two groups based on the median.

Table 11 presents the findings. Comparing Columns (1) to (4), we concluded that the positive relationship between GF and corporate NQPFs is stronger in regions with lower public environmental concern and within larger enterprises. Moreover, both the estimated coefficients of ESG and the interaction term between GF and ESG are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, confirming the significant role of corporate social responsibility in promoting the impact of GF on NQPFs, thereby supporting Hypothesis H4.

Specifically, the significant positive correlation in low-attention regions may stem from the fact that in areas with weaker external supervision, green finance serves as a more pivotal market-based incentive, effectively compensating for the lack of informal regulation and guiding corporate green transformation. In contrast, in high-attention regions, although the coefficient is positive, its weaker significance (10% level) suggests that stringent public scrutiny may have already compelled firms to undertake environmental initiatives, thereby diminishing the marginal effect of GF. The heterogeneity in firm size indicates that, compared to small- and medium-sized enterprises, large enterprises demonstrate a more significant response to GF policies, owing to their more robust governance structures, stronger financing capacity, and systematic advantage in integrating green financial resources into long-term strategies. Most notably, a significant positive synergy exists between ESG performance and corporate response to GF. Firms with higher ESG standards generally possess more robust internal governance structures and more transparent environmental information disclosure, enabling them to absorb and allocate green financial resources more effectively, thereby facilitating technological innovation and enhancing production efficiency.

To further validate our argument, we introduced the quality of corporate environmental information disclosure (EID) as an alternative moderator. As shown in Column (6), the coefficient for the interaction term between GF and EID (GF × EID) is −0.1366, which is significant at the 1% level. While high-quality EID is intended to reduce information asymmetry and guide green finance to green enterprises, in practice, it may lead to unexpected distortions. It can become a heavy compliance burden for firms, diverting resources from green innovation. Some firms may also engage in “greenwashing”, meeting policy requirements with superficial reports rather than substantive actions. This misleads the allocation of green funds. Therefore, this result highlights the complex role of transparency mechanisms in the GF-NQPFs relationship, indicating that under certain institutional conditions, improved disclosure may initially constrain rather than facilitate the productivity benefits of GF.