1. Introduction

Grocery shopping is a fundamental aspect of daily life in households. In recent years, the number of local grocery stores in rural areas of Germany has significantly declined, leading to increased distances between residential areas and supply locations [

1,

2]. Consumer demands for a broader product range, competitive pricing, and higher quality, coupled with greater car mobility and the increasing consolidation of trips, have collectively contributed to the reduction of locations in the primary brick-and-mortar retail network [

3,

4,

5,

6]. This trend is particularly pronounced in rural areas, where small-scale business formats are in decline, resulting in strained access to basic supplies [

7,

8,

9]. Certain demographic groups, such as the elderly, individuals with limited mobility, those living alone or as single parents, and households without a car, are especially impacted by the increasing distances to the nearest grocery store, often making walking access unfeasible [

1,

10]. The gaps in local supply have also led to a deterioration in the quality of life for affected populations [

11,

12]. To address these emerging grocery supply gaps in peripheral rural areas and to revitalize town and village centers, alternative and decentralized supply formats are becoming increasingly relevant. As online grocery retail continues to play a limited role in food supply within rural areas, small-scale stationary supply formats are regaining importance [

4,

13].

In the literature, various terms are used to describe these low-threshold formats, such as “corner stores” or “village shops” [

3,

14,

15]. In this article, the term “small rural grocery store” is consistently used, defined as a stationary establishment with a broad (though not deep) range of goods and services for daily needs, potentially offering additional services, with up to 400 m

2 of retail space, situated in towns with fewer than 5000 inhabitants [

16]. Many small rural grocery stores are operated by locals or local initiatives, often through the purchase of shares and/or volunteering [

5]. Historically, local grocery retail in rural areas has relied on small-scale business formats, such as village or corner shops, family-run bakeries, butcher shops, fruit and vegetable markets [

7], as well as farm shops, and more recently, vending machines or petrol station sales. Among these formats, only small rural grocery stores offer a wide range of food products. It is often assumed that small rural grocery stores are not a viable alternative for daily grocery shopping for most of the population, even when they are the closest shopping option. This perception is primarily due to the limited product range and higher prices compared to supermarkets and discount stores [

2,

10,

14]. Beyond their role in food supply, small rural grocery stores also fulfill a social function within the local community [

5,

17,

18], which is confirmed by numerous studies but has not been thoroughly analyzed from the customer’s perspective. Given that each rural community has unique contextual factors, the presence of small rural grocery stores holds different social significance for the local population [

11,

19,

20]. Additionally, considering that community acceptance may influence the success of such stores [

18], understanding the consumer perspective is particularly important, yet it has been examined in only a few studies [

21,

22,

23].

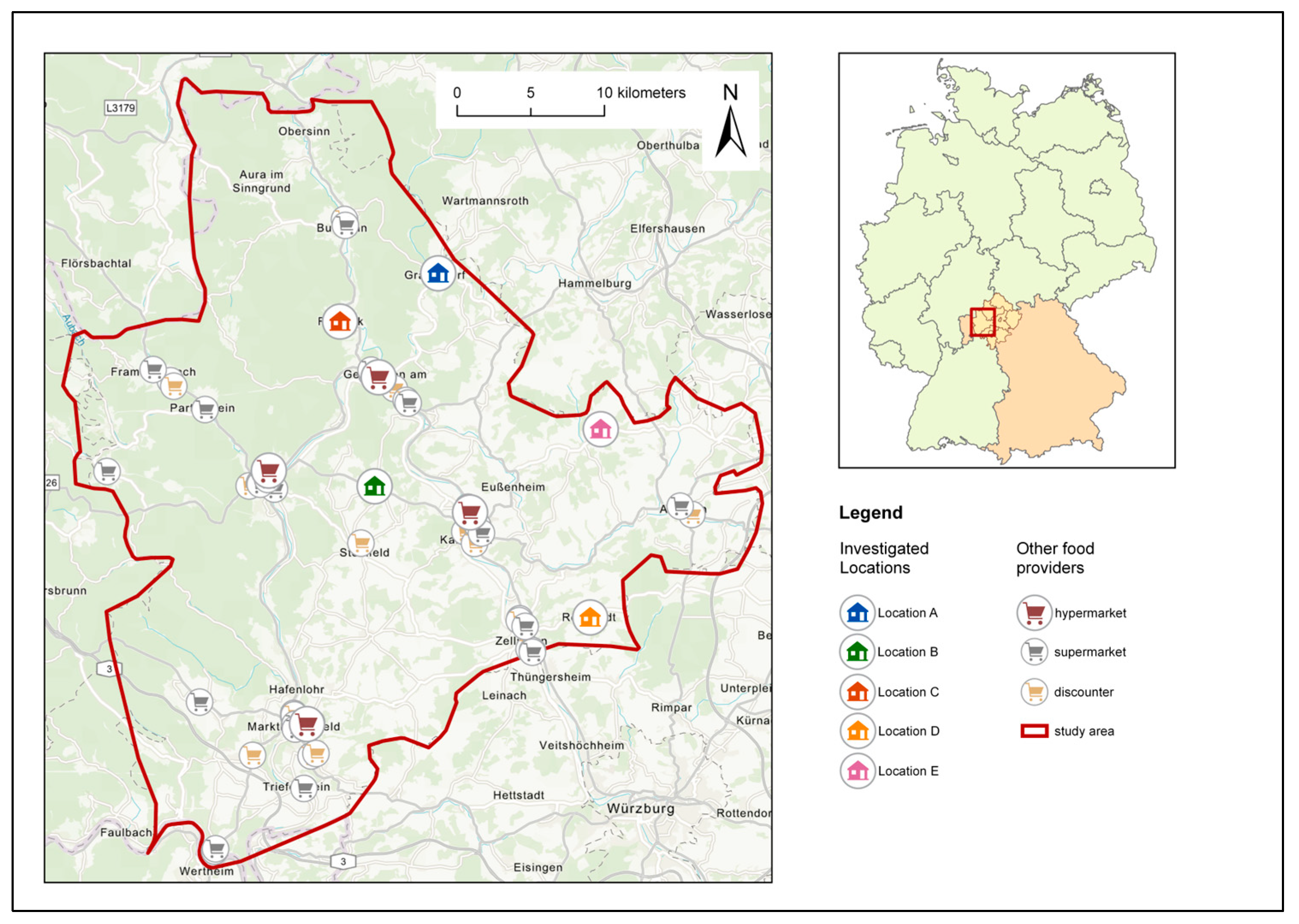

This article investigates whether, and to what extent, small rural grocery stores play a role in the grocery shopping behavior of residents in rural areas and how consumers perceive them. The focus is primarily on small rural grocery store customers, to gain a deeper understanding of the actual usage conditions. Additionally, the article seeks to determine the extent to which small rural grocery stores can be considered as an alternative food supply for customers and whether they can bridge the gaps in local food supply. To this end, a quantitative consumer survey was conducted in five selected small rural grocery stores in the Mainfranken region of Bavaria, Germany. The study focuses on documenting the shopping behavior of small rural grocery store visitors and analyzing mobility and accessibility, as well as social aspects. Initially, the challenges associated with decentralized food supply in rural areas and their underlying factors are outlined.

2. Conceptual Framework

Accessibility, proximity, and product range are key factors in the success and longevity of small rural grocery stores. In consumer research and in the modeling of market and catchment areas, these factors have typically been operationalized using criteria such as catchment areas and maximum distances or the variety of offerings [

8,

24]. However, this simplistic approach, which is primarily based on spatial bridging, necessitates a more comprehensive conceptualization and operationalization of accessibility. It is important to recognize that consumers are selective when shopping for food and their behavior varies greatly over time [

25,

26,

27,

28]. A contextual understanding of accessibility in daily supply is also becoming increasingly relevant in discourses on social justice. Issues of social (in)justice, as well as approaches from social science inequality research and spatial justice, are gaining prominence in trade and consumer research [

29].

According to an initial classification by Shaw [

30], physical (ability) and financial restrictions (assets) are critical factors shaping life in poorly supplied rural areas. Shaw [

30] also identifies a third factor: consumer mental attitudes toward food, which can (negatively) influence their perception of grocery stores and, therefore, contribute to the emergence of these rural areas. Jürgens [

23] expands on the concept of “mental food deserts” in the context of studies in German-speaking countries, exploring whether differing perceptions regarding local supply conditions, shopping habits, and living structures of consumers contribute to the emergence and perpetuation of “real” food deserts, to the detriment of certain population groups.

For rural households with access to a car, grocery shopping close to home has become less important due to increasing mobility and specific preferences, as well as the tendency to combine errands [

13,

31]. Greater mobility and larger activity ranges mean that grocery shopping increasingly forms part of everyday routines. Consequently, grocery shopping is often done not only close to home but also near places of work or other activities. These coupled activities now play a significant role in the choice of shopping locations [

6]. The concept of proximity has evolved and is no longer solely based on walking accessibility, as was originally the case, but rather on car accessibility. Furthermore, proximity is now understood as a dynamic space-time construct shaped by life experiences, perceptions, and individual capacity to process information, making it somewhat subjective [

32]. As a result, an inadequate local supply situation cannot be automatically equated with dissatisfaction among the affected population, as food supply is often ensured despite longer travel times [

33,

34]. Even though the majority of rural households with a car are satisfied with the supply situation, regardless of age, as several studies have shown [

33,

35], future challenges may arise due to demographic changes and increasing consumer spending. Limited mobility, due to physical limitations or the inability to drive or afford a car [

36], combined with greater distances to grocery stores, notably restricts autonomous grocery shopping.

According to Jürgens [

2], the basic product range of small rural grocery stores is better suited for occasional shopping, purchasing items forgotten during bulk shopping at supermarkets (“forgetful shopping”) or buying necessities, and the stores are generally used for these purposes [

17,

19,

21]. However, recent adjustments to the retail format of small rural grocery stores have been observed in various locations. Some community-run stores serve more than just a supply function; they also act as meeting places and venues for social exchange, particularly in regions with limited access to other infrastructure [

15,

37,

38]. This dual role has been explored in various international studies, highlighting similar dynamics across different rural contexts. Research from the Netherlands emphasizes the importance of small rural grocery stores as hubs of community interaction and their positive impact on social place attachment, especially in areas with declining populations and aging demographics [

20]. Swedish studies, on the other hand, have shown that the closure of village shops can weaken social ties, further destabilizing rural communities [

15]. Moreover, community-driven initiatives have proven to be a sustainable approach for maintaining rural grocery stores. Herslund and Tanvig [

37] demonstrate that locally supported stores in Denmark not only enhance local access to essential goods but also strengthen community cohesion, making them more resilient to economic and demographic challenges. Newer and more modern small rural grocery stores, which pursue a multifunctional approach and aim to offer more than just basic groceries, complement their offerings with additional services, such as a café corner [

5,

10,

19]. It has also been demonstrated that providing gastronomic services in rural areas can positively impact the local quality of life [

39]. Nonetheless, the continued existence of small rural grocery stores is partially dependent on the support of local residents [

31]. Against this background, it is important to understand which types of customers frequent small rural grocery stores, for what purposes, and with what frequency. Multidimensional segmentation approaches are used in consumer research to identify differences between consumers [

40,

41]. In addition to socio-demographic characteristics, consumer attitudes and value orientations play a key role. This allows for more precise insights into consumer behavior, as different lifestyles lead to different purchasing practices [

42]. Based on consumer surveys, such segmentations can be methodologically carried out using cluster analysis procedures. An U.K. study on the shopping habits of rural residents in Scotland by Broadbridge and Calderwood [

21] argues that understanding customer perspectives, their shopping behavior, and their attitudes and preferences is critical for the success and long-term survival of small rural grocery stores. By understanding their customers and tailoring their services to better meet their expectations, rural stores can more likely sustain their operations (ibid.). A customer-oriented approach, therefore, enables small rural grocery stores to stay competitive in increasingly challenging retail environments. Addressing this topic is the primary aim of this paper.

4. Results

The descriptive and multivariate analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS. To gain a detailed understanding of the role of small rural grocery stores in grocery shopping behavior, a Two-Step cluster analysis was employed to identify different types of store customers. Since commonly used hierarchical cluster analyses can only be conducted with metric-scaled variables, the Two-Step method was chosen, as it is particularly suited for large datasets and variables of varying scale levels [

50,

51]. The algorithm is also effective in detecting outliers and determining the optimal number of clusters, ensuring a more reliable classification of data [

51]. Additionally, the results it generates are easy to interpret (ibid.), making it an ideal tool for this study to identify distinct customer types. Four variables regarding social and behavioral aspects were utilized for the cluster analysis, two being categorial (targeted use of store as a social meeting place and financial support), as well as two ordinally scaled variables (importance of social exchange in the store, shopping frequency). The automatically identified four-cluster solution was then crossed with demographic and other relevant explanatory variables to evaluate the results.

4.1. General Findings

Among the 238 respondents, a higher proportion are women (60.8%) compared to men (39.2%). The small rural grocery stores are predominantly frequented by older participants. The age group 65 to 74 is the most represented at 27.5%, while 13.6% are over 75. In contrast, only 8.5% of respondents are under 30 years old. When comparing the age distribution of this sample to that of the overall population in the examined villages, it is evident that respondents aged 65 and older are overrepresented in this sample (average: 24%), whereas younger respondents under 30 are severely underrepresented (average: 22.2%). The distribution of middle-aged respondents (30 to 64 years) in the sample, which constitutes 50.5% of the total, closely matches the overall population (average: 48.7%) [

46].

In this survey, two-person households constitute the largest group, accounting for 36.2% of respondents. The average household size is 2.51. Additionally, 92.4% of households own a car. The sample’s characteristics are consistent with those of similar rural areas in Germany and thus can be considered representative of other rural regions in the country [

52]).

It is also noted that the majority of surveyed shoppers (81.1%) are residents of the respective village. Using ArcGIS Pro software (Version 2.2.0) and respondents’ places of residence, it was found that individuals from neighboring villages, located 5 to a maximum of 10 min away by car, also frequent the surveyed stores.

4.2. Accessibility of Small Rural Grocery Stores and Other Grocery Stores

To gain a better understanding of the significance of small rural grocery stores in everyday shopping, the survey also included questions about other food supply locations. Participants provided information on the location and accessibility of their last three grocery shopping trips outside the investigated stores. As shown in

Table 2, the respondents can reach the small rural grocery store in an average of 5.2 min. Overall, most customers travel to the store by foot (42.6%), car (35.4%), or bicycle (20.3%), while public transport plays a minimal role in accessibility. For trips to other grocery stores, respondents predominantly use their car (90.6%), with other modes of transport being relatively insignificant.

The respondents reported walking times to the store averaging 5.3 min, with times ranging from 30 s to 30 min. Notably, 91.1% of these customers can reach the store within 10 min on foot. Car users, who make up 35.4% of respondents, report an average travel time of 5.7 min, with 29.8% of these users choosing to drive even for journeys of two minutes or less. Bicycles are particularly important for older individuals when accessing local suppliers. Among those who cycle to the store, the majority are in the 50 to 64 age group (35.4%) and the 65 to 74 age group (27.1%). The average reported cycling time is 3.9 min.

4.3. Attributes and Shopping Behavior of Customers and Their Connection Towards Small Rural Grocery Stores

The majority of rural store customers shop at the store several times a week (57.1%). Weekly shopping is performed by 22.3% and daily shopping by 13% of respondents. Daily visits are predominantly made by those aged 65 and older (54.9%) and single adults (38.7%). Among those who visit the stores less than once a month (1.7%), the majority are younger respondents under the age of 29 (75%). Using the correlation coefficient by Pearson, a strong relationship was identified between the place of residence and shopping frequency (C = 0.829, p < 0.001). When examining the connection between shopping frequency and travel time to the store with the Spearman correlation coefficient, a weak correlation was determined (rsp = 0.161, p = 0.05).

In terms of the purpose of the visit, shopping for necessities is the most frequently mentioned reason in the sample (62.2%), followed by weekly shopping (13.1%). Spontaneous shopping ranks third at 9.8%, ahead of “forgetful shopping” (5.1%). A small proportion of respondents (6.9%) visit the store primarily as a social meeting place. Notably, half of these responses are attributed to customers of Store D, which features the largest café corner among the stores, with additional gastronomic offerings. When asked if the store is specifically used as a social meeting place, 48.9% of the participants across all locations responded “yes” and 51.1% with “no”. If the responses are considered separately by location, major differences are evident in this regard. Over half of the customers in stores with more extensive additional services (larger café corner) (Stores B and D) affirmed this question, while the majority of customers in stores lacking a place to linger (Store A) and those in villages with alternative social spaces (Store C) responded “no”. Regarding the connection between shopping frequency and the targeted use of the store as a social meeting place, 61.3% of customers who shop daily at the rural grocery store indicated that they use it specifically as a social meeting place. Also, 41.5% of the respondents are financially involved in the stores. In every surveyed location, the proportion of financially uninvolved customers exceeds that of supporters. Those financially involved are aged between 50 and 74 and visit the store several times a week for essentials and weekly shopping. Financially uninvolved shoppers are younger, between 30 and 49, and primarily visit the stores for essential and spontaneous purchases. Notably, 61.3% of daily purchases and 50.7% of purchases made several times a week are attributable to financially uninvolved customers.

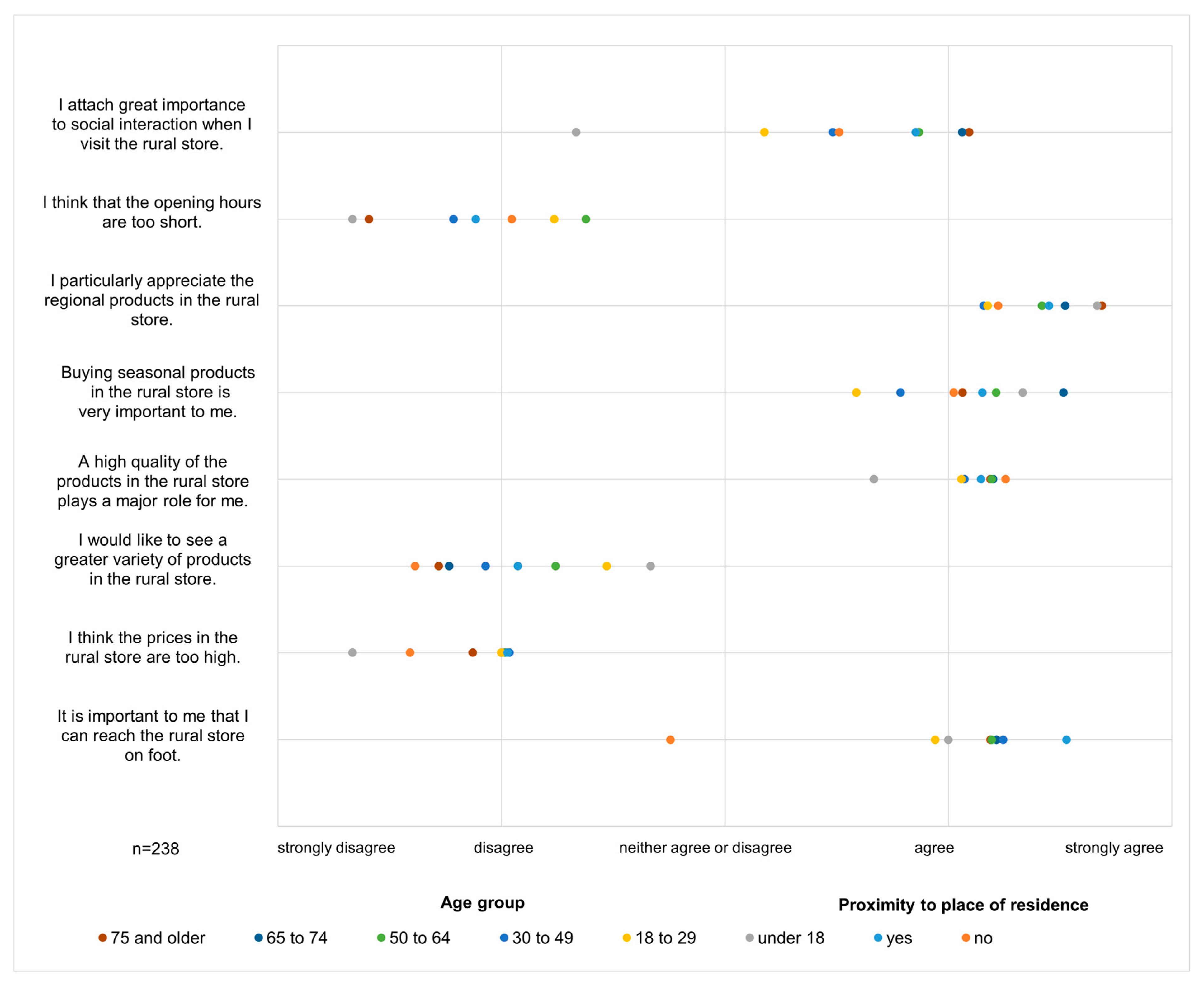

The survey also assessed customers’ attitudes towards various aspects of local supply using a five-point Likert scale.

Figure 2 presents the mean responses by age and place of residence. The survey reveals that older respondents place higher value on social aspects compared to younger participants. Opening hours are generally not considered too short. Older respondents tend to value regional and seasonal products more highly. Product quality is rated as very important across all age groups. Most participants are satisfied with the product variety, with 67.9% not desiring a greater variety. Prices are generally not seen as too high (68.8%). Participants residing close to the store are more likely to agree with statements regarding proximity, social exchange, the importance of regional products, and seasonal products, as well as a desire for greater product variety. Conversely, participants living further away are more likely to agree with statements about product quality and the perception of short opening hours. A visible difference is observed in the importance of accessibility on foot between local participants and those from different residences.

As the surveyed small rural grocery stores operate under different local conditions, it is crucial to evaluate these aspects on a location-specific level (see

Figure 3). Visitors to stores A, B, and D generally express agreement with statements regarding social exchange, regional products, seasonality, and quality. In contrast, customers of Store E adopt a more neutral position on these issues. Respondents from Store C show a stronger desire for a broader range of products compared to those from other locations. Additionally, participants of Store E differ greatly from those at other locations not only in their views on the importance of accessibility on foot but also in their opinions on opening hours, with no clear consensus. Conversely, respondents from Store D express (very) high satisfaction with the store’s opening hours.

Regarding visitors’ attitudes towards the small rural grocery stores in relation to their financial support, it is observed that, although prices are generally not perceived as too high, financial supporters are more likely to agree with this statement (62.2%) compared to those who are not financially involved, who tend to be more neutral (77.1%). There were no notable differences between supporters and non-supporters in their views on the importance of product quality, origin (including regional and seasonal products), and product variety across the stores. However, the significance of social interaction in the store appears to be less important to those who do not support financially (68.2%), even though a substantial proportion of respondents overall value the social aspect of the store.

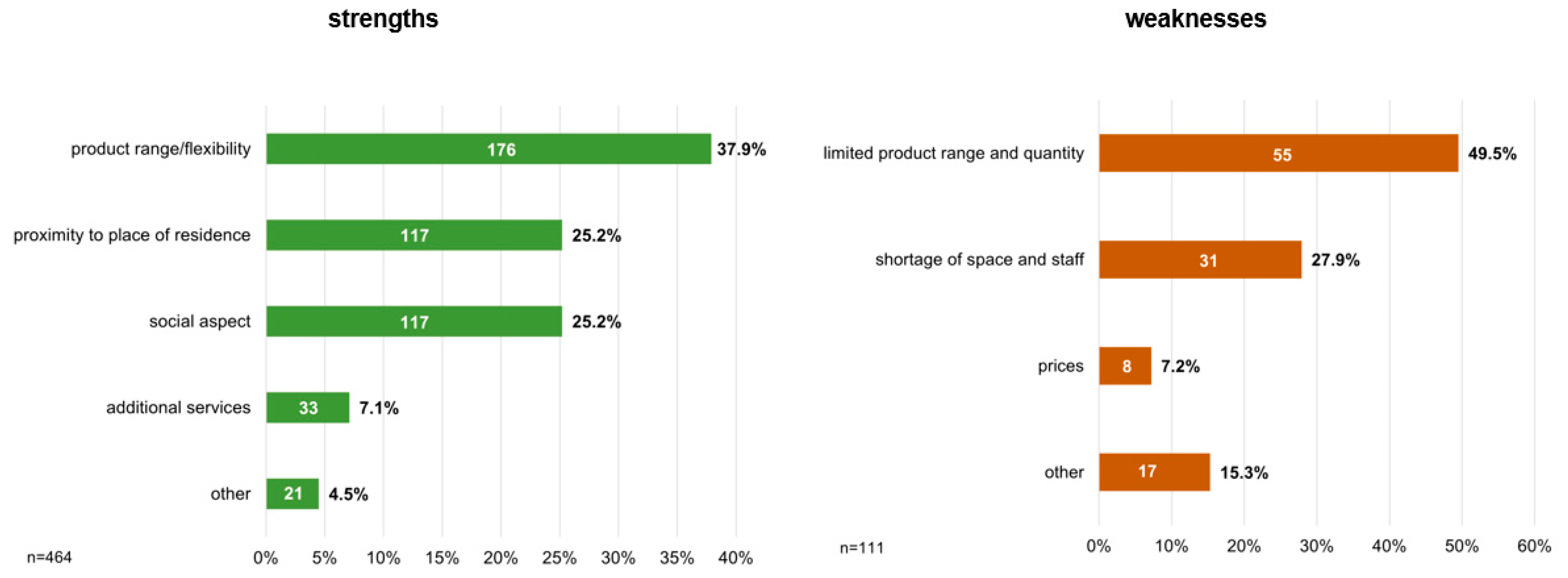

4.4. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Investigated Small Rural Grocery Stores

The respondents had the opportunity to specify strengths and weaknesses of the small rural grocery stores through an open-ended question. The responses were then categorized into key themes, as illustrated in

Figure 4. An analysis of these responses revealed that customers perceive the product range as a major strength, cited by 37.9% of respondents. This includes the variety of fresh products, such as fruits, vegetables (including organic options), dairy, and meat products, as well as regional goods. The flexibility of the product range is also appreciated, with stores accommodating special orders or expanding their selection based on customer feedback. Additionally, 25.2% of respondents valued the proximity of the stores or the fact that groceries are available within the locality. The social aspect of the store is also valued by 25.2% of respondents, highlighting social interactions (5.4%), the friendly atmosphere (3.2%), welcoming staff (6.3%), the store’s role as a community meeting point (7.1%), and the commitment and cohesion of the local residents (3.2%). Additional services such as café corners or small post offices were noted as strengths by 7.1% of respondents. Other positive remarks (4.5%) included the price–performance ratio, the range of organic products, the opening hours (notably for store D), and special discounts and events.

Concerning negative aspects of the stores, 49.5% of respondents of the open question named product range as a weakness, as the selection of products is limited, and only small quantities of goods are provided. Furthermore, it is claimed that the necessary groceries (e.g., staple foods) are provided, but it cannot be compared to a supermarket with a greater variety of products. Therefore, the product quantity and range are controversial, as they were mentioned as both a major strength and weakness. The shortage of retail space and staff were also mentioned, with 27.9% of the overall responses. According to the respondents, the limited space in the locations is not comfortable when shopping for groceries, due to barriers like store shelves (6.3%). Other responses in this category include the shortage of staff (1.8%), limited opening hours (13.5%), and long waiting times (2.7%). Also, a small share of 3.6% listed the unfriendliness of staff as a weakness. Further weak points listed by the survey takers include the lack of or inadequate parking facilities in front of the store (15.3%).

Analyzing strengths and weaknesses by age groups reveals that older respondents particularly value the social interactions provided by the small rural grocery stores. The flexible product range is recognized as a strength across all age groups. However, the limited product range is also most frequently cited as a weakness by respondents aged 50 to 64 (31.5%) and 30 to 49 years old (27.8%). In stores C, D, and E, this criticism is distributed similarly, whereas stores A and B see minimal mention of this issue.

Comments regarding high prices are notably prevalent among respondents from store A, with half of the price-related criticisms coming from this location. Notably, the criticism of high prices comes mainly from those who do not use the store as a social meeting place (75%) or who are not financially involved in supporting the store (75%). Furthermore, respondents aged 50 to 74 (64.6%), particularly those frequenting store E, highlight the lack of sufficient staff and space as weaknesses (41.4%). Other concerns, such as limited store area and inadequate parking facilities, are reported similarly across age groups but are more frequently associated with visitors of store C.

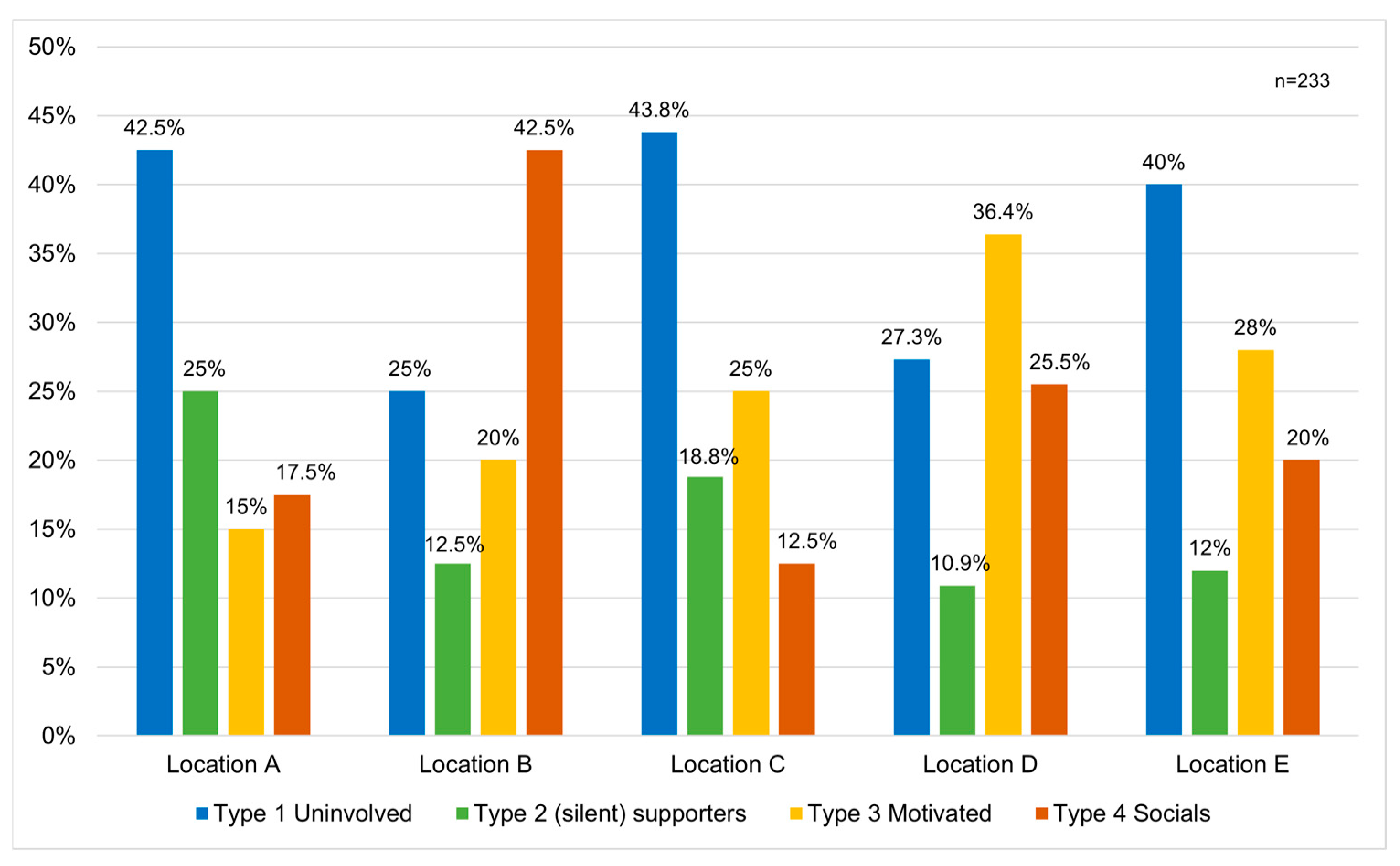

5. Types of Small Rural Grocery Store Customers

Inspired by Jürgens [

53], who classified consumers into five types based on attitudinal questions, a Two-Step cluster analysis was conducted to identify specific customer types in our survey. This analysis used key variables related to social aspects, financial support, and shopping behavior to categorize customers. The analysis identified four distinct types of store customers in rural areas.

Table 3 summarizes these customer types, highlighting their central characteristics, while

Figure 5 illustrates their distribution across the various stores.

The first customer type, referred to as the Uninvolved (occasional buyers), is characterized by their lack of engagement with the small rural grocery store both as a social meeting place and through financial support. This group primarily consists of younger individuals who typically live alone or with one other person. They tend to shop at larger supermarkets or discount stores in the nearest town center, with an average travel time between 12.9 and 14.4 min. Their visits to the small rural grocery store occur approximately once a week or more frequently, primarily for essentials and spontaneous purchases. While they generally prefer to use a car for transportation, walking to the store is also common among them. Accessibility on foot is relatively less important for this group. Social interactions within the store hold little relevance, and they place less importance on the seasonality and regionality of products compared to other customer types. Instead, they value the store’s proximity to their residence and its flexible product range. A notable weakness identified by this group is the store’s opening hours. This type is predominantly represented among respondents from stores C, E, and A.

The second type, known as the (silent) supporters, are distinguished by their financial support to the store, although they do not use it as a social meeting place. This group mainly includes individuals over the age of 50 who typically live in two-person households. They visit the small rural grocery store several times a week, primarily for essentials, with weekly shopping being a secondary purpose. Like the Uninvolved, they also shop at larger supermarkets in the nearest town center, with an average travel time ranging from 14.8 to 17.5 min. These customers prefer walking to the store, taking an average of 5.3 min. For them, the accessibility of the store on foot is very important. While they consider the availability of regional products essential, the quality and seasonality of products are less critical. They perceive the store’s prices as reasonable and find the opening hours adequate. Social interactions in the store are of relatively lesser importance. Strengths mentioned by this group include the store’s proximity and product range, while weaknesses include limited product choice, insufficient retail space, inadequate parking facilities, and a sense of anonymity. This type is notably present in stores A and C, with a similar representation in stores D and E.

The third type, termed the Motivated, is unique in that its members both financially support the small rural grocery store and use it as a social meeting place. This cluster is primarily composed of women aged between 65 and 74. They typically make purchases several times a week, with a high proportion of these being weekly shopping trips. They shop at other grocery stores approximately twice a month, with an average travel time between 13.6 and 16.5 min. Their journey to the store is mostly on foot, averaging five minutes. For this group, accessibility on foot is very important. They place great value on purchasing regional and seasonal products and do not desire a broader product variety. The store’s opening hours are deemed sufficient, and the prices are not considered too high. The product range is seen as both a strength and a weakness. Additionally, this group appreciates the social aspect and proximity to their residence. Weaknesses noted by the Motivated include insufficient parking facilities and a lack of voluntary engagement. This customer type is primarily associated with store D, followed by store E.

The fourth and final customer type, the Socials, are distinguished by their use of the store as a social meeting place without providing financial support. This group predominantly consists of middle-aged women and elderly individuals who generally live alone or in a family of three with one person under 18. They frequent the store several times a week for essentials, as a meeting place, and for weekly shopping. They usually reach the store on foot, with an average walking time of 6.8 min, and visit other shopping locations once a week, with travel times averaging between 11.5 and 12 min. Social interaction is particularly important to this group. They value regional, seasonal, and high-quality products. They find the store’s opening hours and prices satisfactory and are generally pleased with the product range. Proximity to their residence is also seen as a strength, while short opening hours are mentioned as a negative aspect. Most of the Socials are found at stores B and D, with fewer at stores E, A, and C.

6. Discussion

Using a quantitative study design across five small rural grocery stores in Main-Spessart, Germany, we investigated the role of alternative food supply formats in the shopping behaviors of customers in rural areas characterized by low local supply quality. The majority of survey participants reside in the village where the store is located, though residents from surrounding villages also shop there. Notably, trips of less than two minutes to the store were frequently made by car, which can be attributed to topographical factors, such as hilly terrain in the examined villages, and/or physical limitations of the customers. The survey predominantly included female and older respondents (ages 65 to 74), aligning with Zibell et al.’s [

1] findings that older women living alone are more reliant on local amenities within walking distance, partly due to the scarcity of driver’s licenses and vehicles among older single women in rural areas. It can also be assumed that older people who live alone consciously use the place as a social balance. Activity couplings, which can substantially influence grocery shopping behavior [

6]), were less relevant in our study due to the high proportion of older individuals, the very rural setting, and the travel characteristics. The dominance of older respondents over 65 suggests a potential link to a lack of employment, which, according to Zibell et al. [

1], is associated with increased time availability for mobility and shopping. Additionally, a notable proportion of participants reported using bicycles for grocery shopping, an uncommon choice in rural areas with great distances to shopping locations [

6,

54]. This is likely due to most respondents living close to the store and thus covering shorter distances.

The predominance of essential purchases among participants can be attributed to lower purchasing volumes and smaller expenditures typical of visits to small rural grocery stores, as noted by Küpper and Eberhardt [

17]. According to Neumeier and Kokorsch [

14], the stores are mainly suited and visited for occasional shopping or for shopping groceries that were forgotten to buy elsewhere (“forgetful shopping”). However, the results regarding the purpose of visit reveal that the share of “forgetful shopping” is low, while weekly shopping is the second most frequently cited by participants. Also, contrary to the statement of the authors, there is a noteworthy share of surveyed customers (57.1%), that visit the store not occasionally but several times a week for buying groceries. Daily shopping is particularly common among respondents aged 65 and over and those in single-person households, whereas younger respondents use the store less frequently. Respondents who shop on foot and require not more than ten minutes to reach the store visit several times a week. The frequency of visits declines with decreased accessibility on foot. A key observation is that the targeted use of a store as a social meeting place is highly dependent on the additional infrastructure provided. For instance, Store D, with facilities like a café corner, serves as a social meeting place for 61.8% of its visitors, as well as Store B, with 62.5% of surveyed respondents using it as a social venue. This contrasts with Store A, without a café corner, where only 32.5% of respondents view it as a social meeting place. Store C, with a small café corner, sees only 35.3% of respondents using it for social interaction, possibly due to its limited selection of baked goods, few seating options, and the presence of an independent café next door.

Our study identified a high proportion of financial supporters among all respondents. However, in each store, the number of financially uninvolved customers exceeds that of supporters. Eberhardt et al. [

5] as well as Paddison and Calderwood [

55] found that financially contributing and/or involved customers are more likely to shop frequently at community-run stores. In our study, this correlation was not observed, as the majority of daily shoppers were financially uninvolved. Among the respondents who shop several times a week, the share of supporters and non-supporters is almost identical. Furthermore, financially supporting respondents perceive the store prices as higher. Overall, no noteworthy impact of financial support on purchase frequency or store ratings was detected.

The analysis of strengths and weaknesses reveals that, despite their limited range, small rural grocery stores effectively meet customers’ daily needs. Their fresh produce offerings, including bread, baked goods, fruits, vegetables, sausages, and cheeses, are particularly valued. The convenience of purchasing (fresh) food close to home is especially appreciated by older individuals who prefer local shopping options due to a lack of alternatives [

20]. The social aspect of these stores is consistently emphasized, especially by respondents who use them as a meeting place, with mentions on community cohesion, resident engagement, and the store’s meeting point function. The café corner is primarily mentioned as a strength by young local participants (18–49 y). According to Gieling et al. [

20], the presence of a café can contribute to the social connectedness of younger rural residents. Therefore, the social aspects of the store do not merely apply to older age groups. The importance of proximity to the store is notable, especially for those living nearby. Moreover, while the increased demands for quality and the availability of seasonal and regional products apply to shopping in both supermarkets and discounters, these factors also influence shopping behaviors in small rural grocery stores. Respondents also highlighted the availability of organic products as a strength, with overall satisfaction regarding prices, product variety, and opening hours, though these factors vary by store due to differing surrounding conditions.

Survey participants who live close to the store tend to be more understanding of higher prices, limited product selection, and shorter opening hours compared to visitors from outside the village. This aligns with Gäumann and Meier Kruker [

56], who suggest an awareness of the need to support local stores even if shoppers also frequent larger grocery outlets. Marshall et al. [

10] note that a more positive attitude towards these stores often accompanies lower expectations, given the availability of alternative food sources. Furthermore, Broadbridge and Calderwood [

21] and Trembošová et al. [

57] emphasize that staff friendliness, which was mentioned by the respondents as a strength (6.3%), can distinctly impact rural store success, affecting outlet choice and fostering greater loyalty. The small percentage of participants listing unfriendliness as a weak point (3.6%) can be connected to mentions of longer waiting times due to the shortage of staff in some of the surveyed rural stores and, therefore, appears rather as an exception. The analysis of customer types indicates that the more socially oriented types (Motivated and Socials) prefer stores with extensive food ranges (particularly fresh produce) and a larger café corner. These groups rate the store’s prices, opening hours, and product range more positively and value local amenities within walking distance. Conversely, customers of community stores with less variety and no dedicated social space are more likely to belong to the Uninvolved or Silent Supporters clusters. Uninvolved shoppers typically use the store for essential or spontaneous purchases, tend to shop at larger supermarkets, and regard social interaction as less important. Altogether, the identified customer types highlight the significant impact of location characteristics on shopping behavior and social aspects.

This study acknowledges several limitations. The provider perspective was not considered, and the attitudes and behaviors of non-users, which are crucial for the long-term success of stores [

18,

23], were not included. Future studies could address these aspects. While face-to-face surveys are valuable for gathering in-depth data and achieving higher response rates, they are susceptible to certain biases, such as social desirability bias and the Hawthorne effect [

58,

59]. Despite measures to mitigate these biases, such as assurances of anonymity and a neutral question design, some participants may have provided socially desirable answers rather than reflecting their true behavior or beliefs. For instance, when asked about weaknesses of the rural grocery stores, some participants may have refrained from mentioning negative aspects out of concern that their responses could be overheard by others, including store staff or other customers. While this potential bias cannot be entirely ruled out, the inclusion of anonymous written questionnaires alongside face-to-face interviews helped mitigate its impact by providing an alternative means for participants to express their views more openly.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that in rural regions with a sparse density of full-service grocery stores, decentralized formats can ensure a basic level of food supply. Without these decentralized options, there would be insufficient foot-accessible food sources in the examined areas. Thus, small rural grocery stores can play a crucial role in shaping shopping behavior. The findings highlight that the accessibility of decentralized services within walking distance is particularly vital, especially for older individuals residing nearby who exhibit a higher degree of social engagement. Additionally, the study identifies the added value of an expanded selection of fresh food and supplementary services, such as a larger café corner. Enhanced gastronomic offerings and increased opportunities for social interaction on-site can be considered significant success factors for small rural grocery stores. Supporting rural grocery stores in integrating social infrastructure, for instance through targeted subsidies or funding programs, could strengthen both their economic viability and social sustainability. Village shops are good examples of sustainability in practice in its three dimensions:

- ➢

Economic sustainability: A large proportion of the range of fresh produce comes from regional production (some of it also from organic production).

- ➢

Environmental sustainability: In addition to taking into account ecological criteria in the regional selection of products and short supply chains, local supply is secured, and distance bridging and motorized private transport by consumers are reduced.

- ➢

Social sustainability: We were able to identify aspects of social sustainability, in particular in the fact that village shops are very important as social meeting places.

Our customer segmentation, which employs a multidimensional approach, reveals relatively homogeneous groups and provides more nuanced insights compared to one-dimensional approaches (e.g., age, vehicle availability). The identified customer types indicate that those who use the community store as a social meeting place visit more frequently and express greater satisfaction with the store’s product and service range. This suggests that the surrounding conditions and specific features of the stores greatly impact how consumers perceive them as viable and useful alternatives. By considering these factors, small rural grocery stores can effectively address gaps in local food supply.

The data indicate that despite their limited product range, small rural grocery stores are a viable option for meeting residents’ daily needs, particularly due to their fresh goods offerings. This model of supply not only plays a vital role in fulfilling essential needs but also enhances local community cohesion and social bonds. By acting as a social anchor point in the local context, small rural grocery stores play a role in maintaining and promoting mental wellbeing, especially among older, less mobile population groups. The insights provided by this customer-oriented study can assist policymakers in the study area and beyond in understanding the conditions under which small rural grocery stores thrive. By identifying key factors, such as customer shopping behaviors and the impact of social infrastructure, decision makers can develop targeted support measures to strengthen and maintain alternative food supply formats in rural areas. The study highlights the significant role small rural grocery stores play in ensuring food accessibility and enhancing the quality of life in underserved rural areas. By identifying distinct customer types and their specific needs, the findings provide valuable insights for tailoring store offerings and infrastructure, such as integrating social meeting spaces. Policy implications include the need for targeted support and funding mechanisms to sustain these stores as vital components of rural infrastructure. Encouraging multi-functional spaces within grocery stores could enhance their role as both supply hubs and community centers, fostering social cohesion and addressing accessibility challenges. Given the representativeness of the sample, these findings may also be applicable to other regions within the national context. Furthermore, as similar characteristics are observed in other rural areas of Central Europe [

60], the results could offer valuable insights for those regions as well. Future research can use qualitative methods to analyze the needs, social structure, and shopping behavior of users in greater depth on the basis of the findings obtained. Furthermore, a focus on residents who do not use small rural grocery stores can also provide an understanding of the impact in the local context.