Abstract

This study investigates the influence of technostress (Tech) on the well-being (WB) of employees in manufacturing sectors employing Industry 4.0 in Turkey, examining the effect of work exhaustion (WE) as a mediator in the association between technostress and well-being. How digital leadership (Dg) moderates these relationships is analyzed and discussed accordingly. This article also presents strategies for digital leaders to mitigate employees’ technostress in the digital transformation era and discusses their positive role. Using the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) framework and Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, data were gathered from 329 workers employed at three manufacturing firms located in Istanbul. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test this study’s hypothesis. The results indicate that increased technostress notably reduces employee well-being, primarily because it heightens work exhaustion. Moreover, robust digital leadership effectively lessens these negative impacts, underscoring its value in managing technological stress. This research explains the importance of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3) for better health and well-being practices in workplaces. It suggests practical implications for organizations, including developing digital leadership skills, routinely assessing technostress, and applying targeted actions to sustain employee health during digital shifts.

1. Introduction

Within the framework of the current technological era, demonstrated by the swift advancements in the digital era with its ever-present connectivity, companies and their staff encounter challenges that have never been seen before, as well as prospects [1]. The unescapable influence of the digital era within the place of work has essentially changed the manner in which one works and has influenced employment burdens, resources, plus overall staff proficiency [2]. The creation of a digital world has been integrated into most aspects of professional and personal lives, which has led to recent research into the delicate components of work-affected stress, employment safety, and the overall impact of digitalization [3]. The evolution into a digital era requires that employers combine company processes towards the goal of advancing their technological improvements but also update themselves simultaneously to ensure that progress continues, which in turn can be stressful [4]. The bombardment of constant communication in relation to technology and information, which in turn has become known as technostress, relates to the stress faced by those who have interacted with technology [5]. Factors of technostress, for example, the overload of technology, invasion of technology into lives, and the complex nature of technology, can generate a variety of negative results, including exhaustion at work, loss of employee satisfaction, and a reduction in company responsibility [6]. Whilst the improvements gained by technology should be considered, such as in relation to production and access to information, the overuse of technology can also create a negative impact on employees’ mental health [7]. This paper is associated with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG3), focused on providing a healthy existence and encouraging positive mental health for all ages [8].

Previous research offered some views on how technostress can generate adverse results, such as [9,10,11,12,13,14] staff discontent, a higher rate of exhaustion, and a decline in employee obligation and efficiency [12], which in turn influence turnover intention [15]. Existing research has not analytically examined the mediation process in relation to technostress and the relationship between employees’ mental health and their work environment. Therefore, with the narrow scope of the literature and the JD-R theory (Bakker A.B. & Demerouti E., 2017 [16]), our research will discover how work exhaustion mediates this relationship. Furthermore, relating to the business sector, demonstrating that technology-motivated stress is increasing, leading to emotional exhaustion and a reduction in mental health, highlights the crucial role of digital leadership. Moreover, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory provides further theoretical support by positing that stress results primarily from resource loss, while resource gain becomes especially critical in the context of such loss [17]. In this scenario, digital leaders perform as drivers of vision, leading their establishment to adapt to ever-changing situations and thereby improving sustainability [18]. Nevertheless, existing papers on the moderating role of digital leadership within this framework, specifically in the growing economy of Turkey, are limited. We aim to contribute to the literature by exploring the aspects of digital leadership as a crucial moderator that possibly mitigates the adverse effect of technostress on employee well-being.

Technostress was primarily established in a paper by Craig Brod, 1984 [19], and can be described as any harmful condition created by interactions with modern technology in an unhealthy manner, with examples of technostress including stress and addiction [20]. Therefore, technostress can be described as a specific stress relating to the use of computer technology, created by the rapid change in technology occurring, and the impression of being incapable of coping with these changes [21]. During and following COVID-19, there was a spike in employees experiencing New Ways of Working (NWW), due to a large proportion having to work from home. NWW are a combination of HRM practices that offer employees greater flexibility, autonomy, and release in relation to when, where, and how they work and the extent of the work [11]. As stated by Andrulli et al., NWW comprise five aspects: (1) the time and place of independent working, (2) productivity, (3) availability of company information, (4) flexibility in managing relationships, and (5) workplaces that are accessible and open. As a result, manufacturing sector employees have changed to more digitally designed work and education in digital technologies throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to extensive technostress never before seen [9]. The enforcement of a “remote” working model, combined with a lack of specific training and a lack of a changeover phase, led to an increase in stress. In the model, the leadership of a team virtually regulates the measurable impact on team performance, specifically when leaders effectively engage through a virtual platform [22]. This study highlights that while evolving to digital platforms offers a unique set of challenges that need careful leadership and engaged followers, virtual team members can offer more productivity with the right setup [22]. This area was specifically noticeable, bearing in mind that new technologies are considered to be more successful when employees can embrace and want them. Employee comprehension of new technology aspects prior to their implementation in the workplace is crucial. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [23] expedites this comprehension by reviewing how staff propose to encompass these technologies and exactly how effective they expect them to be. This model has experienced revisions, highlighting the potential for further external factors to impact the acceptance of technology and, as a result, usage [24]. The circumstances of well-being are intimately related to stages of technostress, which occur when technology is perceived as a threat or a source of concern, and when there is a disparity between job demands and available resources. The manifestation of technostress causes numerous harmful responses, for example, burnout and a reduction in mental health [10].

The fourth industrial revolution (4.0) has effectively altered the face of business procedures and was officially accepted as a fundamental initiative in Germany (2013), thereby recognizing the industrial innovators creating a revolution in the manufacturing division [25]. There is a critical issue in relation to the complete business environment in Turkey that adapts and innovates with education and highlights the benefits of the implementation of a complete Industry 4.0 attitude. To also highlight the importance of how organizations can experience issues during the transition from previous industrial ideas to the new attitudes of Industry 4.0 [26], as an indicator of the relative performance of similar countries that are undergoing the transition to Industry 4.0, currently, Turkey sits in 31st place in the European ranking (Hayriye Atik, Fatma Ünlü, 2019 [27]). In Turkey, it is required to gauge organizations’ levels of understanding and the recognized complexities faced when acclimatizing to Industry 4.0. The absence of suitably qualified employees and the requirement for extensive investment have been seen as a restriction for companies to overcome. Organizations foresee the requirement for personnel to be qualified in order to manage data, data security, analytics, software design, and manufacturing procedures. Furthermore, they expect that with the digitalization of production comes significant advantages, including but not limited to reduced production overheads, improved profits, increased output, better customer satisfaction, improved competition, increased hygiene standards, and a reduction in labor charges [28].

This research is based upon Demerouti’s recognized Job Demands–Resources Model (JD-R model) [29]. This JD-R concept indicates that amongst the physical, emotional, social, or company aspects that need addressing, the skills that the employee possesses are job stresses and trials and could lead to employee stressors. Furthermore, there are additional areas of any job, whether it be physical, psychological, logistical, or social, that assist the staff to accomplish goals and achieve performance targets and inspire professional development or lessen the expenditure of employment demands. The relationship between employment demands and resources for the job to be completed influences motivation, employment operation, and staff well-being [13].

Previous studies have recognized that technostress might reduce organizational commitment, productivity, and job satisfaction [15], and it might increase information overload, cognitive demands, and communication costs [15]. However, there is still limited empirical evidence on the specific processes through which technostress undermines employee well-being. Additionally, several studies analyze the role of digital leadership on well-being [12,30,31,32]. However, the significant role of the variable as the moderator in the link between technostress and well-being is not explored. To bridge this gap, this research focuses on investigating the mediating role of work exhaustion in the relationship between technostress and employee well-being. Moreover, by incorporating mediation and moderation within an integrated analytical framework, this study advances the distinctive comprehension of the relationship between technological stresses, emotional resources, and leadership subtleties.

The balance of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 appraises the theories and literature and proposes hypotheses; Section 3 expands the methodology, involving data collection (329 employees) and analysis; Section 4 presents outcomes and conclusions; and Section 5 examines findings and the broader literature. The findings of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of technostress in the manufacturing Industry 4.0 and align with sustainable strategies under SDG 3.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Technostress and the Well-Being of Employees

During the recent past, the integration of technology has created a comfortable work environment; however, the excessive incorporation of technology within the workplace creates significant challenges regarding technostress [33]. The specter of technostress creates a helplessness in dealing with new information and communication technology (ICT) in a mentally beneficial way [5]. Currently, it has become prevalent that technology is challenging the mental health of employees, creating an environment of technostress, leading to a sinister undercurrent of ICT [13]. This shift in work practices and the demands placed within the workplace can lead to significant pressure on staff, resulting in a decline in their emotional, psychological, and physical well-being (Raj & Goute, 2025 [33]).

The five primary dimensions of technostress come in the following forms: techno-overload, techno-uncertainty, techno-complexity, techno-security, and techno-invasion. Techno-overload, being one of the five dimensions, manifests in the form of people having to work harder, faster, and longer [34]. The term techno-complexity refers to the manner in which complex technological skills may be required to understand ICT, leading to individuals feeling insufficiently able to utilize the technology and thereby spending excessive time to comprehend the required technology [35]. Furthermore, techno-insecurity creates a feeling of insecurity stemming from technology and can initiate feelings of job insecurity because others may be perceived as more competent. The last part of technostress, techno-uncertainty, arises when people are unable to keep up with technological progress, as software and hardware rapidly change [9]. Individuals who judge technostressors, for example, techno-overload and techno-invasion, find that this can be detrimental to their mental health and lead to psychological reactions. Furthermore, individuals who evaluate technostressors, like techno-complexity, techno-uncertainty, and techno-insecurity, find that this hinders their employment and creates an adverse tension due to their inability to deal with them [36].

Previous research encapsulates the direct impact of technostress on mental health [9,10,11,12,13,14,33]. Regardless of the inception of extensive digital technologies, a mounting body of data suggests that its progression faces obstacles, specifically relating to the well-being of employees [34]. Furthermore, technostress has been highlighted as being both directly and indirectly related to mental health, with burnout as a mediator. Research by Sharif et al. [37] offered that technostress moderated the relationship between AI use and individuals’ well-being and successful career paths. Additionally, technostress instigators vary in their interactive and psychological consequences, comprising alterations in job satisfaction, commitment, productivity, and exhaustion [12]. Work engagement is reduced by technostress, leading to burnout and an additional decrease in innovative work engagement [38]. At the same time, increased levels of psychological and emotional well-being are proposed to lessen the technostress experienced by staff [33]. Amongst the five interlaced technostressors, techno-insecurity had a modest impact on employees’ mental health. Both male and female respondents were conscious of the distinctive features of technology processes [14]. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Technostress during enforced work negatively affects employee well-being.

2.2. Work Exhaustion as Mediator

The term work exhaustion signifies overextension and a reduction in individuals’ emotional and physical resources [39]. Emotional exhaustion is generally indicated by physical tiredness and a feeling of psychological and emotional exhaustion [40]. Experimental evidence validates a positive and significant relationship between technostress and emotional exhaustion [9,12,41,42,43]. Therefore, research continually demonstrates that extended exposure to a stressful environment can lead to work exhaustion [12]. Also, technostress is indicated as “reactions of staff to adverse impacts towards technology-connected factors in work”, which has been continually connected to burnout, which appears as “emotional tiredness, depersonalization, reduction in accomplishments personally, and extended stress caused by work” [44]. Furthermore, technostressors can generate many psychological issues, for example, tiredness, anxiety, burnout, petulance, and depression, which all combine to impact one’s psychological well-being [12]. Therefore, when handling the varied technostress creators, individuals may experience a reduction in emotional and physical resources, inevitably culminating in fatigue and exhaustion [12]. As a result, exhausted employees convey reduced energy, plus lower resources, resulting in their reduced personal accomplishments. Previous research has demonstrated that techno-overload, the occasion when employees are overwhelmed when using technology, could lead to emotional fatigue and exhaustion. Therefore, those who experience such emotional fatigue often feel physically drained and, as a result, are unable to work to their full potential [42]. The outcomes suggest that the more regularly individuals experience techno-induced disruptions (as an indicator of techno-unreliability), the symptoms of burnout become stronger [45]. Companies with a healthy environment offer employees suitable resources to retain a healthy lifestyle during work, for example, mental health programs to encourage healthiness. The opposite applies when organizations have an unhealthy environment and, as a result, do not encourage or offer healthier options, thereby leading to employees feeling overworked and exhausted [46]. Additionally, work-related exhaustion may serve as a significant driver of stress in the workplace, leading to reduced workability and increased exhaustion. This, in turn, reduces the effectiveness of workers, which can lower employee motivation, decrease physical activity, and compromise work–life balance [47].

Considering the above evidence, it is essential to understand why and how work exhaustion affects the relationship between technostress and workers’ well-being. Particularly, ref. [9] indicated that job exhaustion mediates the relationship between technostress and employee well-being in the workplace. On a similar note, Ma et al. (2021) [48] found that the association between technostress and work–life balance was mediated by emotional exhaustion. Moreover, technostress, caused by digital platforms in isolated work locations, exaggerates mental stress involving technological tiredness and exhaustion, thereby unfavorably impacting personal well-being [12]. Also, Munandar & Utami (2020) suggested that “burnout can interact to explain the pattern of theoretical relationships connecting technostress and job satisfaction” [49]. Additional research indicates that exhaustion at work plays a mediating role connecting the three aspects of technostress (techno-invasion, techno-security, and techno-complexity) and knowledge concealment. This mediation route also encompasses specific workplace behaviors, like when Zhang and colleagues [50] discovered that when Research and Development employees encounter high technostress, it leads to work fatigue. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2.

Technostress during enforced work positively affects work-related exhaustion.

H3.

Employees’ work exhaustion during enforced work negatively affects their well-being.

H4.

Work exhaustion of employees mediates the negative association between technostress and well-being.

2.3. Digital Leadership as a Moderator

The surge of technostress levels has initiated an amplified examination of the mitigation methods for technostress, involving positive leadership behavior. The job demand resources (JD-R) theory suggests that a high-quality leader–employee exchange can assist in reducing staff stress, as managers can offer required employment resources to contradict the job demands presented by the adoption of technology [51]. Beyond the JD–R theory, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory posits that resource loss is the primary component in the stress process. Resource gain, in turn, is portrayed with an increasing importance in the framework of loss. The COR theory has been successfully employed for forecasting a range of stress outcomes in organizations [17]. It also leads to interferences that change people’s resources or their environments [17].

Furthermore, several studies have explored the specific leadership qualities as potential moderators in the correlation between technostress and well-being [51]. Digital leadership involves a leader’s capability to propose a specific and significant vision for the process of digitalization, together with the ability to execute the proposals to enable the vision to be fulfilled [4]. Additionally, digital competence and leadership aptitude combined describe the qualities of a digital leader in the current era of the digital revolution [52]. Also, a potential buffering effect of health-stimulating leadership between these perils and employee well-being was noticeable for ineffective technical support [53]. Moreover, Bregenzer and Jimenez also found that leaders can mitigate the potentially crucial effects of stress when there are limited opportunities for education and digital skill development. However, additional risk elements may lead leaders to employ differing leadership styles to enhance their employees’ well-being, particularly since the physical distance between leaders and virtual teams can make healthy, encouraging leadership more challenging. The study presents strategies for digital leaders via communication, transparency, and trust [54]. Communication has a fundamental role in digital leadership [55]. To keep employees encouraged, a transparency about the goals and progress of the digital transformation is essential [54]. Trust and transparency are especially interconnected in separated teams that cooperate virtually [56]. Digital leaders who want to cultivate trust must be transparent in their communication (Norman et al., 2010 [57]).

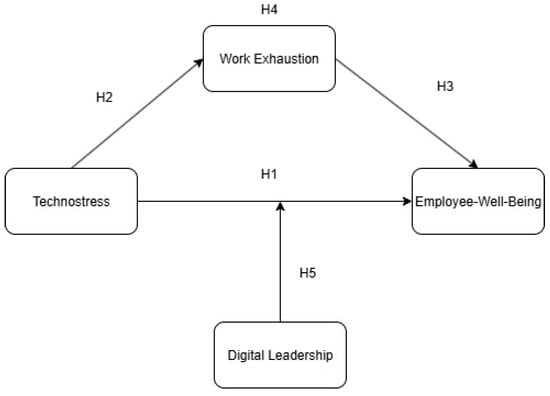

Therefore, organizations may recognize the requirement for specialist digital management training to lead digital jobs efficiently. This is critical as technology-enabled leadership can hurt employees’ well-being if carried out ineffectively or destructively [58]. Similarly, not every leadership approach helps mitigate technostress; for example, a highly authoritarian management style has an increased effect, while low-authoritarian leaders are protective of the relationship between workaholism and technostress, especially within a collection of entirely remote workers. Therefore, an authoritarian management style should be prevented, and training leaders to be mindful of its impact seems to be critical [59]. Additionally, Chatterjee et al. [60] discovered that digital leadership competence decisively buffers the relationship between employee implementation and employees’ performance and between the work–life balance of employees and organizational success. Likewise, the discovery by Lathabhavan & Kuppusamy (2024) [18] suggested position implications for digital leadership, digital education, enablement, and organizational performance. Also, Bauwens [51] commented that encouraging leaders lessens the impact of techno-complexity. As a result, and based upon the above literature, we devise the following hypotheses. Figure 1 describes our conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. Source: authors’ development.

H5.

Digital leadership buffers the negative relationship between technostress and employee well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure

This study was conducted among workers in 3 manufacturing companies in Istanbul, Turkey. This study selected the Industry 4.0 manufacturing sector as the sample context because of the profound transformations occurring at the operational level. The justification behind choosing this sector is that the shift to Industry 4.0 is directly affecting the nature of the work and workers by initiating novel interactions between them and machines [9]. The adoption of automation and the uncertainty surrounding the future of work can trigger intensified stress, anxiety, and burnout among employees [61]. Furthermore, the rapid pace of technological change can create a sense of insecurity and overwhelm, which can negatively impact mental health if not appropriately managed [25]. Therefore, focusing on the manufacturing sector undergoing digital transformation provides a timely and relevant setting to explore how technostress affects employee outcomes and how digital leadership may buffer these effects.

3.2. Questionnaire Design

We utilized a questionnaire with a total of 36 items using a 5-point Likert scale (1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree) (Table S1). Before this study, a pilot study was conducted to minimize response bias, and the research questionnaire was refined accordingly. As the scales for measuring were established in previous research and the data were not recently generated, we followed the Classical Test Theory (CTT) process as opposed to the Item Response Theory (IRT). This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design (Decision No. 2024-2025/07, dated 26 May 2025).

3.3. Procedure and Data Collection

Sample size calculation was accomplished using G*Power 3.1 software to conduct a linear multiple regression fixed model test with two predictors, a small effect size (f2 = 0.05), an acceptable alpha value (α = 0.05), and a maximum power (1 − β = 0.95). The software suggested that a minimum of 312 participants was expected. The study participants provided their informed consent to participate and completed the survey. The primary data was obtained via a structured questionnaire from employees in retail, logistics, R&D, finance, and administration, representing a wide range of professional domains. We utilized a simple random sampling method by circulating 500 questionnaires to staff in three Istanbul firms in the manufacturing sector. Males comprised the majority of these participants (56.8%), while females represented the minority (43.2%). The main proportion of respondents (76.5%) was between the ages of 25 and 40. A significant proportion (66.8%) reported moderate job durations of one to ten years. Moreover, 16.7% of the employees had worked for less than 1 year, and 16.4% had worked for more than 15 years. Employees operated in a diverse variety of working sectors, including logistics (19.8%), retail (27.4%), research and development (R&D) (17.0%), administration (13.7%), finance (13.1%), and other sectors (9.1%) (see Table S2).

3.4. Measurement

Established scales from previous research were compiled into a questionnaire to measure the constructs. Technostress was evaluated with 16 items designed by Wang et al. [9], which comprised four elements: techno-overload, techno complexity, techno uncertainty, and techno insecurity. Each was measured with 4, 5, 4, and 4 items, respectively (see Table S1). Cronbach’s alpha for technostress was 0.975. Work exhaustion and employee well-being were measured with 4 and 5 items, respectively, from a scale constructed by Wang and colleagues [9]. Cronbach’s alpha for exhaustion was 0.951, while the value for employee well-being was 0.971. Additionally, digital leadership was assessed with 6 items from a scale designed by Lathabhavan and Kuppusamy [18]. The digital leadership tool was measured with 3 items, and digital leadership skills were also measured with 3 other items (see Table S1). Cronbach’s alpha for digital leadership was 0.982.

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis

SmartPLS 4 was used to test this study’s hypothesis. Testing both the outer (measurement) and inner (structural) model involves several systematic steps. The evaluation of the outer model primarily focuses on assessing the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and model fit. The inner model includes a Path Coefficient Estimation, Significance Testing, the Coefficient of Determination (R2), and Predictive Relevance (Q2).

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB)

This study analyzed the CMB by measuring the HTMT. According to [62], the CMB identifies when all the correlation values among the constructs are less than 0.90. The authors confirm that there is no CMB in the model.

4.3. Outer Model Assessment

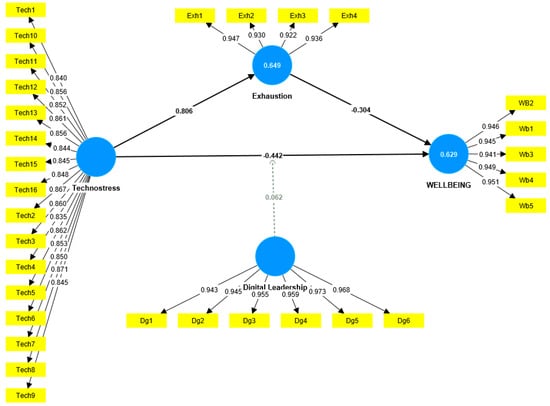

The outer model (Figure 2) shows the hypothesized effect of technostress on employee well-being, which consists of work exhaustion as a mediator and displays the interaction effect of digital leadership. In the outer model assessment (Figure 2), all outer loadings are more than the threshold of 0.70, which confirms that each observed variable has a strong correlation with its construct.

Figure 2.

Outer model coefficients. Source: authors’ development.

Table 1 provides an overview of the factor loading values of the latent variables. To measure the outer model, we studied the outer loadings of the factors. We further analyzed Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE) to evaluate convergent validity. Cronbach’s alpha (>0.7) and CR (>0.7) values were confirm to be within the acceptable threshold values. Moreover, the results reflected that all AVE values were more than 0.5. So, we confirm that the convergent validity is satisfactory (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Outer loading, construct validity, reliability, and AVE.

The Herterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) criterion was applied to measure the discriminant validity. According to Table 2, HTMT values below 0.90 endorse the existence of discriminant validity amongst the variables of the study.

Table 2.

HTMT matrix.

The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) for the models is 0.026, which is well below the conventional threshold of 0.08 and therefore indicates an excellent overall fit in terms of the average residuals between observed and predicted correlations. The normed fit index (NFI) for the estimated model is 0.952, above the common 0.90 cutoff, demonstrating that our proposed model explains the data substantially better than a null baseline model.

4.4. Structural Model Assessment

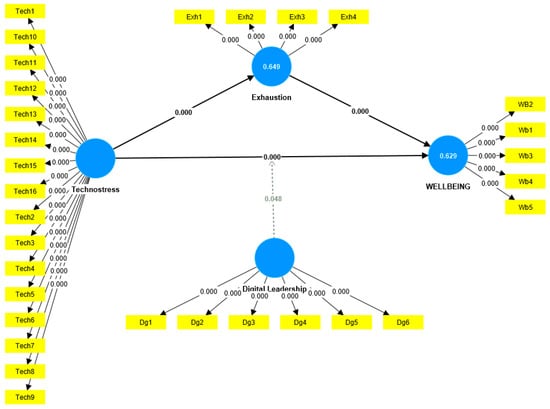

The inner model measurement was conducted through PLS-SEM BT (bootstrapping of 5000 resamples). We implemented a path coefficient test, including the original sample (β), sample mean, standard deviation (STDEV), T statistics, and p values. Figure 3 illustrates the structural model of our study.

Figure 3.

Structural model. Source: authors’ development.

Figure 3 illustrates that a substantial portion of the variance in the mediating and dependent constructs (R2 = 0.629 for well-being and R2 = 0.649 for exhaustion) can be explained by the model. These values show a well-adjusted model that goes beyond the significance of individual paths and validates that the proposed paths together account for a significant amount of explanatory power.

PLS-SEM (Smart Pls 4) was applied to analyze the study data. Table 3 reports the standardized path coefficients, β, sample mean, STDVE, t-values, and p-values for all hypotheses. The study hypothesis in the structural/inner model shows a significant result. Along with H1, technostress is associated negatively with employee well-being (β = −0.442, t = 7.879, p < 0.05). In support of H2, technostress displayed a strong positive relationship with work exhaustion (β = 0.806, t = 35.615, p < 0.05). As projected by H3, work exhaustion in turn was negatively associated with well-being (β = –0.304, t = 5.635, p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Hypothesis testing.

4.4.1. Mediation Analysis

To test H4, we assessed the effect of technostress on well-being through work exhaustion using bootstrapping (5000 resamples). As shown in Table 3, the direct effect was supported (β = –0.442, t = 7.879, p < 0.05), and the mediation effect of work exhaustion was significant (β = –0.245, t = 5.541, p < 0.05), indicating that exhaustion at the workplace partially mediated the negative influence of technostress on employees’ well-being. Accordingly, a substantial portion of technostress’s adverse effect on well-being operates through increased exhaustion. Table 3 indicates how technostress negatively impacts employee mental health indirectly and directly through exhaustion at work.

4.4.2. Moderation Analysis

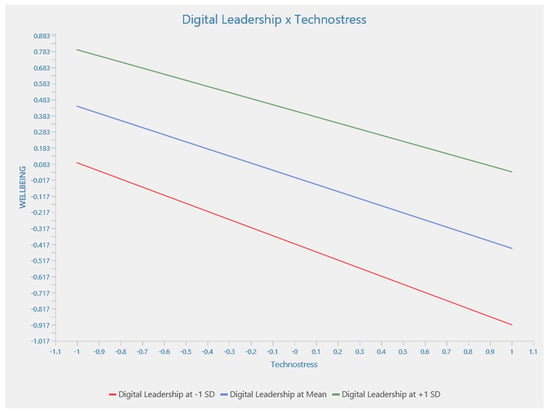

H5 proposed that digital leadership would attenuate the negative technostress–well-being link. The interaction term (digital leadership × technostress) was significant (β = 0.062, t = 1.977, p = 0.048), in line with H5. Simple slope plots (Figure 4) reveal that at one standard deviation above the mean of digital leadership, the negative relationship between technostress and well-being is markedly attenuated, indicating that strong digital leadership mitigates the psychological effects of technology on employees. Conversely, at one standard deviation below the mean of digital leadership, the slope is considerably steeper, showing that in the absence of effective digital leadership, employees experience a sharper decline in well-being as technostress increases. The figure indicates how digital leadership moderates the negative relationship.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of digital leadership on technostress and well-being, simple slope analysis. Source: authors’ development.

5. Discussion

This paper investigates the effects of technostress and its hindrance to employee well-being, including exhaustion from work, and the impact that digital leadership can have in protecting staff from these effects. Collecting a sample of 329 employees from the manufacturing sector in Turkey, we confirmed that all of our hypotheses are significant. Firstly, our research demonstrated that technostress was harmful to employees’ mental and physical well-being. This fell in line with the outcomes of the studies of [9,10,11,12,13,14]. To tackle this, the industry should offer sufficient training and support in relation to the use of AI, encourage work–life balance, and initiate programs for wellness to mitigate technostress and protect employee well-being [37]. Secondly, through analytical research, the mediating role of work exhaustion was reviewed. This result suggests that technostress could drain employees both emotionally and physically, leading to a reduction in the well-being of manufacturing employees in Turkey. Thirdly, through exploring the moderating role of digital leadership, we discovered that the negative influence of technostress can be reduced when the leadership implements an improved level of digital knowledge. Thereby, we emphasize that accepting digital leadership skills is required in the manufacturing sector, which will reduce the negative impact of stress on the well-being of employees. Additionally, by dealing with the current economic, social, and environmental issues that society faces, the new global development goals for the next 15 years concentrate on enhancing prosperity and well-being until 2030. The SDGs should be achieved through multi-stakeholder processes at the national and local government levels that involve companies, civil society, and faith-based organizations [8].

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our results expand the information and technology management data by revealing a potential health issue through technostress and the erosion of employees’ health. Internal or external work stressors may be viewed as malevolent and intentional, rather than unintentional or inadvertent [63]. Previous studies have generally understood technostress as an obstacle to productivity and organizational performance (Binti Abu Talib et al., 2022; Brooks & Califf, 2017; Hsiao et al., 2017; La Torre et al., 2020; Tarafdar et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2020 [5,64,65,66,67,68]). However, our mediation study exposes that work exhaustion acts as a crucial channel, converting technology-related stressors into reduced psychological and physical well-being [9,10]. Furthermore, AI technostress increases fatigue, intensifies work–family conflict, and lessens job satisfaction, even though they may continue to contribute towards output in the organization [69]. Technostress is related to many unfavorable psychological results, ranging from burnout at the job, mental well-being, and a reduction in job satisfaction [10,21,70,71,72,73]. The precise technostress originators that affect employees’ health are a combination of five subcategories: techno-invasion, techno-overload, techno-complexity, techno-insecurity, and techno-uncertainty [9]. At the corporate level, technostress has created a reduction in innovative skills [72], reduced organizational commitment, and increased turnover intentions [74,75].

By defining the consecutive route from technostress to exhaustion, and eventually to mental and physical health, we offer an empirical argument for reconfiguring the management of technology structures to focus on buffering fatigue, which is a sign of health deterioration. This study answers calls from inside the JD-R literature to highlight emerging requirements and resources in Industry 4.0, as proposed by [16]. Technostress, as a rare demand of jobs, exaggerates the reduction in emotional and mental reserves, whereas digital leadership appears as a key job resource that weakens this reduction. This role extends the JD-R paradigm by illustrating how leadership methods can fundamentally reconfigure the interactions between demands and resources in a technology-focused workplace, offering a blueprint for future research on adaptive resource allocation in Industry 4.0. In addition, from the perspective of the COR theory, technostress denotes a process of ongoing resource depletion, leading to exhaustion and reduced well-being, whereas digital leadership functions as a “resource caravan passageway” by supplying instrumental, informational, and social resources to employees [76].

Digital leadership combines dealing with the convoluted challenges and foreseeing trends that occur from developing technologies [54]. Although digital technologies can present superb opportunities for the swift exchange and receipt of information, some managers can have difficulties in implementing ICT as a route for leadership. This highlights the importance of direct leadership training for virtual teams [58]. Amongst the rapid pace of digital change, results like technostress have been realized by organizations and their leaders. Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a fundamental characteristic for encouraging digital leaders to perfect their skills to reduce employees’ technostress by increasing levels of emotion consciousness [54]. The digital changes in the workplace have essentially reformed managerial roles, making digital leadership vital for both staff and organizational continuity [12,53,77,78]. The results focus on the crucial function of digital transformation through improving the influence of leadership on sustainability [78]. Although, current research has focused on the role of leadership in encouraging employees’ commitment to the digital transformation [79]. Results focus on the ability to counteract the psychological effects of technostress. More precisely, digital leadership’s controlling impact highlights the importance of leaders who are required to demonstrate leadership performance shaped to a digital work environment to lessen the stress on employees [53]. Additionally, our research into the moderating impacts of digital leadership skills highlighted an important result: the mediator can mitigate the harmful effects of technostress. More directly, when employees apply digital leadership capabilities, the destructive effects of technostress are diminished [12]. The outcome suggests that digital leadership significantly improves organizational sustainability both directly and indirectly, with digital abilities and a digital organizational ethos [77].

This study has identified several important mechanisms through which leadership mitigates technostress within a work environment. Social support through the employees’ supervisors appears as one of the most crucial processes [53]. Provisions for resources and setting boundaries signify another vital mechanism through which leaders may lessen their technostress [51]. Identification at the early stage and the capability for prevention signify a further mechanism, with strong digital leaders assisting staff to reduce technostress by highlighting the sources of technology-related stress at an appropriate, early time to prevent escalation [80].

5.2. Practical Implications

Our research furthermore offers important implications for businesses, companies, and their leaders. Organizational and technological configurations, together with the legal structure, require adaptation for digital workplaces. Furthermore, we ask organizations to generate a practical working environment for employees. During the recent past, there has been a meaningful upsurge in the application of multi-functional and multi-disciplinary teams to work together to improve the general quality of output. As a result, it would be sensible for companies to create a diverse working party that functions to explore different ideas in relation to knowledge and expertise [9]. Organizations must offer a continual assessment of mental health and relief of stress through management programs to neutralize burnout, digital stress, and technostress [81]. The implementation of eHealth tools to encourage mental and physical health is an efficient method to support staff. Businesses can also benefit from eHealth tools by rapidly obtaining anonymous feedback regarding the mental health of their staff. When there is crucial feedback, the organization can react to prevent adverse outcomes, such as burnout and stress [53]. Principals individually should appreciate the needs of their staff in a digitalized workspace even more significantly than within a traditional work environment and thereby modify their management style appropriately. If staff are working remotely, leaders are required to lead in a health-encouraging manner. To enable this kind of work to succeed, aspects of digitalization can be a benefit, due to some digital tools which permit managers to maintain close contact with their staff, for example, video conferencing and chats [53]. As a result of this research, we urge extensive training and cooperation with AI technologies to lessen technostress and enhance a healthier working environment. Furthermore, encouraging work–life balance and initiating programs focused on wellness will promote employee well-being and thereby improve the performance of the organization, as well as produce less senior management struggles [37].

The research we have carried out offers practical implications for companies, governments, and legislation. Policymakers perform a critical role in defining regulations and a structure to safeguard worker protection in digital work environments. They must integrate legislation for AI-driven workplaces to ensure transparency, justice, and worker autonomy. Algorithmic decision-making should be controlled to prevent disproportionate observations and bias in evaluations of performance [81]. Governments should also initiate algorithmic transparency laws, ensuring that employers must reveal how AI-driven decision-making influences employee conditions. Staff should have the entitlement to contest inappropriate algorithmic evaluations [81].

Our study findings support SDG 3 by demonstrating specific measures that organizations can adopt to mitigate technology-related stress and safeguard employees’ mental well-being. This includes institutionalizing psychosocial risk assessments for technostress amid technological advancements and investing in digital leadership development, encompassing vision, transparent communication, and coaching on new tools to alleviate exhaustion.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

This research is not without its limitations. Firstly, our model depends exclusively on work exhaustion as the mediator; further research should also explore the strain aspects, for example, techno-anxiety [82] and the psychological indifference failure after employment [83], together with resource gain routes like techno-eustress [5] plus flourishing at work [84] to offer a more conclusive report of how technostress impacts employee well-being. Future researchers could also investigate the role of digital leadership in relation to work exhaustion and employee well-being [12]. Secondly, there is a concern in relation to the generalization of the findings, as differing cultures could impact individuals’ opinions and behaviors [85]. Therefore, it is potentially possible that individuals with various experiences could face dissimilar technostress levels, work fatigue, and mental health. We propose that future research should reproduce our research in a variety of contexts, which would offer more insights into the factors concerning culture and the experience of technostress. Thirdly, the sample we targeted was restricted to the specific population of the Turkish manufacturing sector. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge that the findings of this research may not be representative of all industries in Turkey. Further studies should expand the predictive efficacy of this model in other situations and explore a more comprehensive representative model by researching the employees in many different sectors and settings, for example, small- and medium-sized organizations and service sectors. Fourthly, this study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which restricts our ability to draw causal inferences. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to better capture the dynamic relationships between technostress, work exhaustion, digital leadership, and employee well-being over time. Moreover, this research did not include Baby Boomer employees, who may experience significant challenges in adjusting to digital technology due to generational differences. As a consequence, the results may not fully encapsulate the technostress faced by workers of an older generation. Further research should consider targeting this generation to discover their precise responses to Industry 4.0 and their environments. Finally, another limitation is related to the measurement instruments that were adapted from well-validated English scales; their Turkish translations have not yet been psychometrically validated, and future research should confirm their validity in this context.

6. Conclusions

This paper explored the effects of how technostress deteriorates employee well-being in Turkey’s Industry 4.0 manufacturing sector by lessening the emotional and physical resources of employees and considers whether digital leadership can cushion these effects. From the data we received from 329 employees, we found that four dimensions of technostress—techno-overload, techno-insecurity, techno-complexity, and techno-uncertainty—have a negative influence on well-being. Critically, work fatigue appeared as a key mediator, transmitting much of the technostress’s damaging impact. Though digital leadership was demonstrated to be an influential moderator, weakening the strength of the technostress–well-being link when leaders exhibited powerful digital vision, consultation, and support.

The findings provide evidence-based understandings for creating healthier and more sustainable work environments, specifically in technology-focused sectors like manufacturing, thereby supporting the extended agenda of SDG3. Furthermore, by extending the Job Demands–Resources structure to an Industry 4.0 context and the COR theory, our results indicate that technostress is a new crucial job demand that underscores digital leadership as a strategic resource that organizations should support. Practically, manufacturing organizations and policymakers must combine technostress risk assessment protocols in all digitalized projects, employ continuous fatigue observation and recovery procedures, and further invest in specific digital leadership training and development to ensure the well-being of employees amid this rapid technological transformation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17198868/s1: Figure S1: G*power sample size; Table S1: Questionnaire; Table S2: Demographic Information. References [9,18] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.; methodology, N.S.D. and P.F.; software, N.S.D.; validation, P.F. and A.V.; formal analysis, N.S.D.; investigation, P.F.; resources, A.V.; data curation, N.S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.D.; writing—review and editing, P.F. visualization, A.V.; supervision, P.F.; project administration, N.S.D. and P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of Arkin University of Creative Art and design (protocol code: 2024-2025/07 on 26 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to (specify the reason for the restriction).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Trenerry, B.; Chng, S.; Wang, Y.; Suhaila, Z.S.; Lim, S.S.; Lu, H.Y.; Oh, P.H. Preparing Workplaces for Digital Transformation: An Integrative Review and Framework of Multi-Level Factors. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 620766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholze, A.; Hecker, A. Digital Job Demands and Resources: Digitization in the Context of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazan, A.M. The Digitization of Working Life: Challenges and Opportunities. Psihol. Resur. Um. 2020, 18, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeike, S.; Bradbury, K.; Lindert, L.; Pfaff, H. Digital Leadership Skills and Associations with Psychological Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. The Impact of Technostress on Role Stress and Productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.; Laumer, S.; Eckhardt, A. Information Technology as Daily Stressor: Pinning down the Causes of Burnout. J. Bus. Econ. 2015, 85, 349–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharani, A.; Zeifuddin, A.; Safitri, D.A.; Rosada, H.S.; Anshori, M.I. Kesejahteraan Mental Karyawan Dalam Era Digital: Dampak Teknologi Pada Kesejahteraan Mental Karyawan Dan Upaya Untuk Mengatasi Stres Digital. J. Ekon. Bisnis Manaj. 2023, 2, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A. SDG2030: A Sustainable Built Environment’s Role in Achieving the Post-2015 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM Conference, Manchester, UK, 5–7 September 2016; Volume 2, pp. 1149–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ding, H.; Kong, X. Understanding Technostress and Employee Well-Being in Digital Work: The Roles of Work Exhaustion and Workplace Knowledge Diversity. Int. J. Manpow. 2023, 44, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Seah, R.Y.T.; Yuen, K.F. Mental Wellbeing in Digital Workplaces: The Role of Digital Resources, Technostress, and Burnout. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrulli, R.; Gerards, R. How New Ways of Working during COVID-19 Affect Employee Well-Being via Technostress, Need for Recovery, and Work Engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhayyal, S.; Bajaba, S. Countering Technostress in Virtual Work Environments: The Role of Work-Based Learning and Digital Leadership in Enhancing Employee Well-Being. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truța, C.; Maican, C.I.; Cazan, A.M.; Lixăndroiu, R.C.; Dovleac, L.; Maican, M.A. Always Connected @ Work. Technostress and Well-Being with Academics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.M.; Erum, D.; Churi, P.; Moreno Guerrero, A.J. Effect of Technostress on Psychological Well-Being of Post-Graduate Students: A Perspective and Correlational Study of Higher Education Management. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califf, C.B.; Brooks, S. An Empirical Study of Techno-Stressors, Literacy Facilitation, Burnout, and Turnover Intention as Experienced by K-12 Teachers. Comput. Educ. 2020, 157, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J.; Ennis, N.; Jackson, A.P. Resource Loss, Resource Gain, and Emotional Outcomes among Inner City Women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathabhavan, R.; Kuppusamy, T. Examining the Role of Digital Leadership and Organisational Resilience on the Performance of SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024, 73, 2365–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod, C. Technostress: The Human Cost of the Computer Revolution; Longman Higher Education: Harlow, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaif, Z.N.; Sanmugam, M.; Hattab, M.K.; Bensalem, E.; Ayyoub, A.; Sharma, R.C.; Joma, A.; Itmazi, J.; Najmi, A.H.; Mitwally, M.A.A.; et al. Mobile Technology Features and Technostress in Mandatory Online Teaching during the COVID-19 Crisis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.; Martínez-Navalón, J.G.; Gelashvili, V.; Román, C.P. The Impact of Teleworking Technostress on Satisfaction, Anxiety and Performance. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Wahab, N.; Abdullah, N.H.; Rodzalan, S.A.; Rahman, Z. The Linkage Between Virtual Team Leadership Towards Team Performance: A Study at Selected Companies. J. Techno-Soc. 2023, 15, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiadini, A.; Paganin, G.; Simbula, S. Teaching after the Pandemic: The Role of Technostress and Organizational Support on Intentions to Adopt Remote Teaching Technologies. Acta Psychol. 2023, 236, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Tripathi, S.N.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, S. Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employees Working in Industry 4.0 Led Organizations. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoz, F.; Merdin, D.; Ersoz, T. Research of Industry 4.0 Awareness: A Case Study of Turkey. Econ. Bus. 2018, 32, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik, H.; Ünlü, F. The measurement of industry 4.0 performance through industry 4.0 index: An empirical investigation for Turkey and European countries. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 158, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, E. INDUSTRY 4.0 and TURKEY. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2019, 7, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Fried, Y. Work Orientations in the Job Demands-Resources Model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Dana, L.P.; Braga, V. Strategic Change Work-Family Balance, Digital Leadership Skills, and Family Social Support as the Predictors of Subjective Well-Being of Y-Generation Managers. Strateg. Change 2025, 34, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, S.H.; Said, M.; Arifin, Z. The Influence of Digital Leadership on Employee Affective Well Being with the Mediation of Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Job Satisfaction. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 2102–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R.K.; Sjabadhymi, B. Digital Leadership as a Resource to Enhance Managers’ Psychological Well-Being in COVID-19 Pandemic Situation in Indonesia. South East Asian J. Manag. 2021, 15, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.B.; Goute, A.K. Internal Branding and Technostress among Employees—The Mediation Role of Employee Wellbeing and Moderating Effects of Digital Internal Communication. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Yang, R. Exploring the Influence of Individual Digitalization on Technostress in Chinese IT Remote Workers: The Mediating Role of Information Processing Demands and the Job Complexity. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pflügner, K.; Maier, C.; Mattke, J.; Weitzel, T. Personality Profiles That Put Users at Risk of Perceiving Technostress: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis with the Big Five Personality Traits. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2021, 63, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudioso, F.; Turel, O.; Galimberti, C. The Mediating Roles of Strain Facets and Coping Strategies in Translating Techno-Stressors into Adverse Job Outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.N.; Zhang, L.; Asif, M.; Alshdaifat, S.M.; Hanaysha, J.R. Artificial Intelligence and Employee Outcomes: Investigating the Role of Job Insecurity and Technostress in the Hospitality Industry. Acta Psychol. 2025, 253, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Varma, V.; Vijay, T.S.; Cabral, C. Technostress Influence on Innovative Work Behaviour and the Mitigating Effect of Leader-Member Exchange: A Moderated Mediation Study in the Indian Banking Industry. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Early Predictors of Job Burnout and Engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Hassan, I.; Dastgeer, G.; Iqbal, T. The Route to Well-Being at Workplace: Examining the Role of Job Insecurity and Its Antecedents. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 32, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, E.S.; Syed Ahmad, S.F.; Bahari, A.H.; Mohammad Fadzli, F.N.; Mohamad Adzmi, N.S.H. The Effect of Technostress on Emotional Exhaustion and Coping Strategies. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.; Suminar, D.R. Analisis Hubungan Techno-Overload Terhadap Kelelahan Emosional Dan Kinerja Karyawan: Tinjauan Literatur Review. Al-Kharaj J. Ekon. Keuang. Bisnis Syariah 2024, 6, 8267–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasinta, T.; Firdaus, F.; Haqq, Z.N.; Run, P. The Impact of Techno Complexity on Work Performance through Emotional Exhaustion. J. Fokus Manaj. Bisnis 2024, 14, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, S. Teknostresin Iş Performansı Üzerindeki Etkisi; Tükenmişliğin Aracı Rolü. TR-Dizin İndeksli Yayınlar Koleks. 2018, 20, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.C.; Tisch, A. Exploring the Relationship Between Techno-Unreliability at Work and Burnout. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 66, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaluza, A.J.; Schuh, S.C.; Kern, M.; Xin, K.; van Dick, R. How Do Leaders’ Perceptions of Organizational Health Climate Shape Employee Exhaustion and Engagement? Toward a Cascading-Effects Model. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Henning, R.; Cherniack, M. Correction Workers’ Burnout and Outcomes: A Bayesian Network Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Lu, C.Q. The Impact of Techno-Stressors on Work–Life Balance: The Moderation of Job Self-Efficacy and the Mediation of Emotional Exhaustion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munandar, T.; Utami, S. Determinant of Job Satisfaction with Burnout as a Mediation and Teamwork as a Moderation: Study in Bank Indonesia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Rev. 2020, 3, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yu, C. Does Technostress Increase R&D Employees’ Knowledge Hiding in the Digital Era? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, R.; Denissen, M.; Van Beurden, J.; Coun, M. Can Leaders Prevent Technology from Backfiring? Empowering Leadership as a Double-Edged Sword for Technostress in Care. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 702648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, R.; Baguant, P. The Changing Role of Human Resource Management in an Era of Digital Transformation. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2019, 22, 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bregenzer, A.; Jimenez, P. Risk Factors and Leadership in a Digitalized Working World and Their Effects on Employees’ Stress and Resources: Web-Based Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertiö, T.; Eriksson, T.; Rowan, W.; McCarthy, S. The Role of Digital Leaders’ Emotional Intelligence in Mitigating Employee Technostress. Bus. Horiz. 2024, 67, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigre, F.B.; Curado, C.; Henriques, P.L. Digital Leadership: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2023, 30, 40–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L.; Bruni, E.; Zampieri, R. The Role of Leadership in a Digitalized World: A Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 456340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, S.; Avolio, B.; Luthans, F. The Impact of Positivity and Transparency on Trust in Leaders and Their Perceived Effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, T.; Klingenberg, I.; Süß, S. Leadership and Technostress: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2025, 75, 429–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Molino, M.; Molinaro, D.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Ghislieri, C. Workaholism and Technostress During the COVID-19 Emergency: The Crucial Role of the Leaders on Remote Working. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 620310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Giovando, G. Digital Workplace and Organization Performance: Moderating Role of Digital Leadership Capability. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ja’Ara, B. Navigating the Digital Age: Adapting Education with Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2024, 13, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N. Toxic Leadership and Employee Reactions: Examining How Perceived Injustice and Turnover Intentions Influence Counterproductive Work Behavior. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Butterfield, K.D.; Tripp, T.M. No Good Deed Goes Unpunished: How Workplace Reintegration Leads to Unethical Helping and Harming Behavior. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.L.; Shu, Y.; Huang, T.C. Exploring the Effect of Compulsive Social App Usage on Technostress and Academic Performance: Perspectives from Personality Traits. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Califf, C. Social Media-Induced Technostress: Its Impact on the Job Performance of It Professionals and the Moderating Role of Job Characteristics. Comput. Netw. 2017, 114, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xia, Q.; Huang, W. Impact of Technostress on Productivity from the Theoretical Perspective of Appraisal and Coping Processes. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; De Leonardis, V.; Chiappetta, M. Technostress: How Does It Affect the Productivity and Life of an Individual? Results of an Observational Study. Public Health 2020, 189, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binti Abu Talib, S.L.; Jusoh, A.; Razali, F.A.; Awang, N.B. Technostress Creators in the Workplace: A Literature Review and Future Research Needs in Accounting Education. Malays. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. MJSSH 2022, 7, e001625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.T.; Chiang, H.L.; Lin, A.P. Insights from the Job Demands–Resources Model: AI’s Dual Impact on Employees’ Work and Life Well-Being. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2025, 83, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ-Brendemühl, S.; Schaarschmidt, M. The Impact of Service Employees’ Technostress on Customer Satisfaction and Delight: A Dyadic Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, T.J.; Ginsburg, S.; Wright, J.G.; Shachak, A. Technostress as Source of Physician Burnout: An Exploration of the Associations between Technology Usage and Physician Burnout. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 177, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, G.W. HR Technologies and HR-Staff Technostress: An Unavoidable or Combatable Effect? Empl. Relat. 2019, 41, 1120–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Montani, F.; Jamal, A.; Hussain Shah, M. Consequences of Technostress for Users in Remote (Home) Work Contexts during a Time of Crisis: The Buffering Role of Emotional Social Support. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Wu, Y. The Influence of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Creative Cognition of Design Students: A Chain Mediation Model of Self-Efficacy and Anxiety. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1455015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Cucchi, A. Technostress Creators, Personality Traits, and Job Burnout: A Fuzzy-Set Configurational Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Psychiatry Interpersonal and Biological Processes Conservation of Resources and Disaster in Cultural Context: The Caravans and Passageways for Resources. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Jin, X.; Kwak, W.J. Using the New Positive Aspect of Digital Leadership to Improve Organizational Sustainability: Testing Moderated Mediation Model. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, B. Leveraging Leadership and Digital Transformation for Sustainable Development: Insights from Cambodia’s Public Sector. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Shi, X. How Does Platform Leadership Promote Employee Commitment to Digital Transformation?—A Moderated Serial Mediation Model from the Stress Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2025, 83, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Schäfer, R.; Schmidt, M.; Regal, C.; Gimpel, H. How to Prevent Technostress at the Digital Workplace: A Delphi Study. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 94, 1051–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obasi, I.C.; Benson, C. The Impact of Digitalization and Information and Communication Technology on the Nature and Organization of Work and the Emerging Challenges for Occupational Safety and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, R.; Grover, V.; Purvis, R. Technostress: Technological Antecedents and Implications. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. Recovery from Job Stress: The Stressor-Detachment Model as an Integrative Framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, S72–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at Work: Toward Its Measurement, Construct Validation, and Theoretical Refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Comparative Research Methodology: Cross-cultural Studies. Int. J. Psychol. 1976, 11, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).