Disaggregating ESG Mechanisms: The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Pressure in the Financial Performance of Logistics Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Questions

2.1. Direct Effects of ESG on Financial Performance

2.2. Stakeholder Pressure and Mediating or Moderating Mechanisms

2.3. Sector Specific Insights

2.4. Research Questions

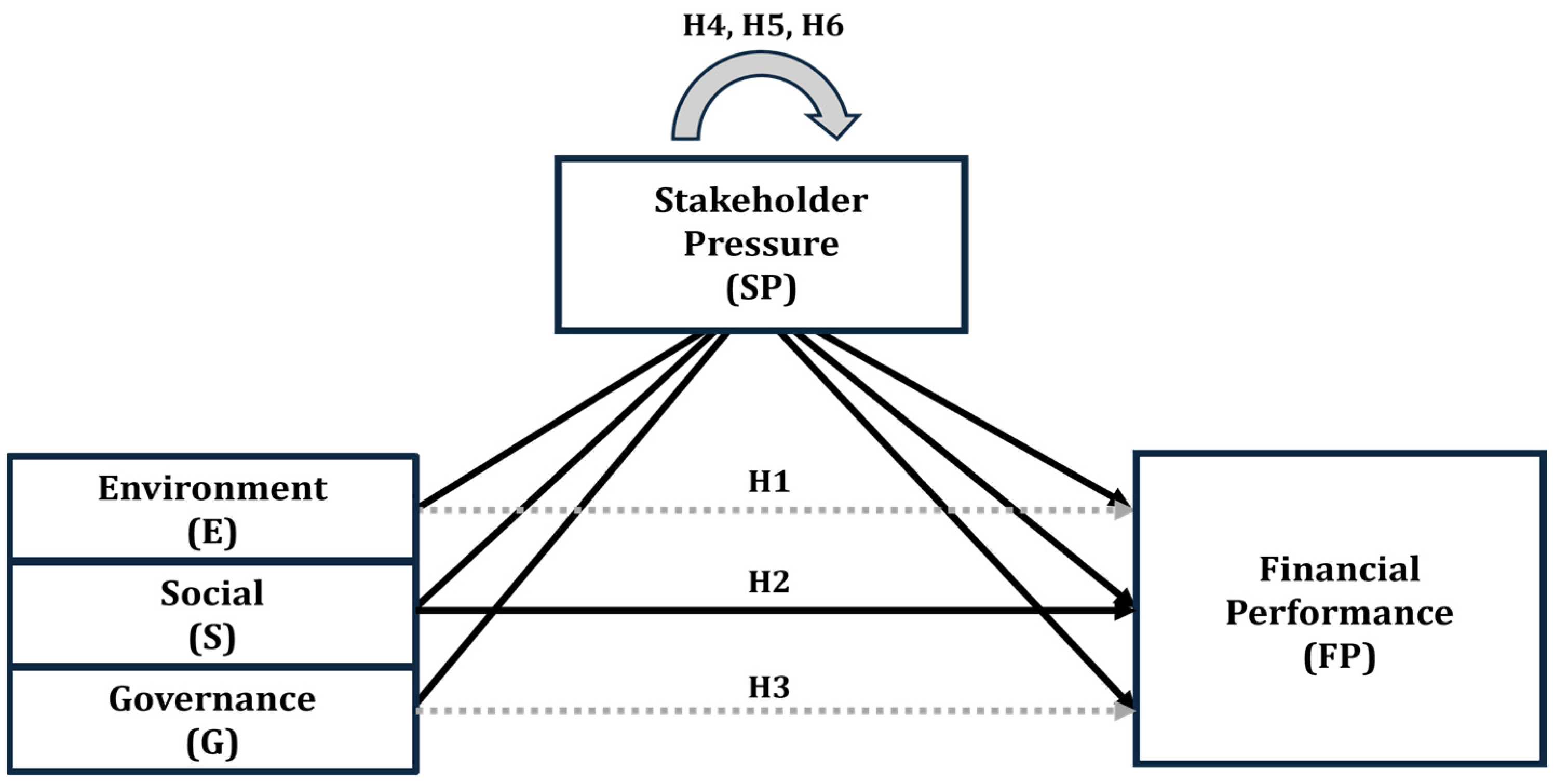

3. Hypothesis Development and Research Model

3.1. ESG Activities and Financial Performance

3.2. The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Pressure

3.3. Research Model

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Instrument and Sampling

4.2. Measures

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

5.2. Model Fit Analysis

5.3. Path and Mediation Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Managerial Implications

8. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research Directions

8.1. Conclusions

8.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| (EA) Environment Activity | Please indicate the level of your company’s engagement in the following environmental practices. | |

| EA1 | Greenhouse gas reduction | |

| EA2 | Environmental impact mitigation | |

| EA3 | Waste management initiatives | |

| (SP) Stakeholder Pressure | Please indicate the level of stakeholder pressure in environmental practices | |

| SP1 | Local community | |

| SP2 | Customers | |

| SP3 | Investors | |

| (FP) Financial Performance | Please indicate the level of financial performance improvement as environmental practices | |

| SR1 | Operating profit | |

| SR2 | Sales revenue | |

| SR3 | Cash flow | |

| Construct | Item Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| (SA) Social Activity | Please indicate the level of your company’s engagement in the following social practices. | |

| SA1 | The promotion of stable labor-management relations | |

| SA2 | The improvement of human rights and safety standard | |

| SA3 | Fostering mutual growth with partner organizations | |

| (SP) Stakeholder Pressure | Please indicate the level of stakeholder pressure in social practices | |

| SP1 | Local community | |

| SP2 | Customers | |

| SP3 | Investors | |

| (FP) Financial Performance | Please indicate the level of financial performance improvement as social practices | |

| SR1 | Operating profit | |

| SR2 | Sales revenue | |

| SR3 | Cash flow | |

| Construct | Item Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| (GA) Governance Activity | Please indicate the level of your company’s engagement in the following governance practices. | |

| GA1 | Strengthening corporate governance framework | |

| GA2 | Adopting ethical management practices | |

| GA3 | Establishing robust legal compliance to ensure transparency | |

| (SP) Stakeholder Pressure | Please indicate the level of stakeholder pressure in governance practices | |

| SP1 | Local community | |

| SP2 | Customers | |

| SP3 | Investors | |

| (FP) Financial Performance | Please indicate the level of financial performance improvement as governance practices | |

| SR1 | Operating profit | |

| SR2 | Sales revenue | |

| SR3 | Cash flow | |

References

- Shakil, M.H. Environmental, social and governance performance and financial risk: Moderating role of ESG controversies and board gender diversity. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Yu, J. Striving for sustainable development: Green financial policy, institutional investors, and corporate ESG performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Barbosa, A.; da Silva, M.C.B.C.; da Silva, L.B.; Morioka, S.N.; de Souza, V.F. Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria: Their impacts on corporate sustainability performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Kanbach, D.K. Toward a view of integrating corporate sustainability into strategy: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iazzolino, G.; Bruni, M.E.; Veltri, S.; Morea, D.; Baldissarro, G. The impact of ESG factors on financial efficiency: An empirical analysis for the selection of sustainable firm portfolios. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Fu, M.W. Conceptualizing sustainable business models aligning with corporate responsibility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, A.C. Logistics and climate: An assessment of logistics’ multiple roles in the climate crisis. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Minhas, U.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Barrane, F.Z. Corporate environmental management: A review and integration of green human resource management and green logistics. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.; Li, H.; Tong, Y.H. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and stakeholder engagement: Evidence from the quantity and quality of CSR disclosures. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder legitimacy in firm greening and financial performance: What about greenwashing temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.; Li, X. ESG performance and corporate value: Analysis from the stakeholders’ perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1084632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Ahmed, T.; Khashru, M.A.; Ahmed, R.; Ratten, V.; Jayaratne, M. The complexity of stakeholder pressures and their influence on social and environmental responsibilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 132038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmig, B.; Spraul, K.; Ingenhoff, D. Under positive pressure: How stakeholder pressure affects corporate social responsibility implementation. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 151–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Environmental collaboration, responsible innovation, and firm performance: The moderating role of stakeholder pressure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito De Falco, S.; Scandurra, G.; Thomas, A. How stakeholders affect the pursuit of the Environmental, Social, and Governance. Evidence from innovative small and medium enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1528–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessa, N.; Akparep, J.Y.; Sulemana, I.; Agyemang, A.O. Does stakeholder pressure influence firms environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure? Evidence from Ghana. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2303790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakanye, R.M.; Van Der Poll, H.M.; Muchara, B. Do companies in different industries respond differently to stakeholders’ pressures when prioritising environmental, social and governance sustainability performance? Sustainability 2021, 13, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. The relationship between sustainable supply chain management, stakeholder pressure and corporate sustainability performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, E. Doing well by doing good: A comparative analysis of esg standards for responsible investment. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 38, 289–311. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmaker, D.; Schramade, W. Investing for long-term value creation. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2019, 9, 356–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lucey, B.M. Sustainable behaviors and firm performance: The role of financial constraints’ alleviation. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoraki, M.E.K.; Giaka, M.; Konstantios, D.; Patsika, V. Firms’ sustainability, financial performance, and regulatory dynamics: Evidence from European firms. J. Int. Money Financ. 2023, 131, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, W.; Hassan, M.K.; Houston, R.; Karim, S.M. ESG activities and banking performance: International evidence from emerging economies. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2021, 70, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruna, M.G.; Loprevite, S.; Raucci, D.; Ricca, B.; Rupo, D. Investigating the marginal impact of ESG results on corporate financial performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, C.; Pazienza, P.; Bartlett, M. Does good ESG lead to better financial performances by firms? Machine learning and logistic regression models of public enterprises in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Thorne, D.M.; Ferrell, L. Social Responsibility and Business, 4th ed.; International Edition; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.T.; Lee, S.Y. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental logistics practices: Is eco-oriented culture a missing link? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2012, 23, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickson, S.L. Organizational identity orientation: The genesis of the role of the firm and distinct forms of social value. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 864–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J.W. Stakeholder relationships and social welfare: A behavioral theory of contributions to joint value creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S. A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, H.; Alnoor, A.; Tiberius, V. Environmental, social, and governance ratings and financial performance: Evidence from the European food industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2471–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; González-Torre, P.; Adenso-Díaz, B. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelbel, J.; Busch, T. Does stakeholder pressure on ESG issues affect firm risk? Evidence from an international sample. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 2013, p. 15874. [Google Scholar]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; Heenetigala, K. Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure for a sustainable development: An Australian study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, L. Losses from failure of stakeholder sensitive processes: Financial consequences for large US companies from breakdowns in product, environmental, and accounting standards. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilt, C.A. The influence of external pressure groups on corporate social reporting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1994, 7, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsantonis, S.; Serafeim, G. Four things no one will tell you about ESG data. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2019, 31, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Theis, J.C.; Vitalis, A.; Young, D. Your emissions or mine? Examining how emissions management strategies, ESG performance, and targets impact investor perceptions. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 15, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Feng, G. Does national ESG performance curb greenhouse gas emissions? Innov. Green Dev. 2024, 3, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Xu, W. Carbon reduction effect of ESG: Empirical evidence from listed manufacturing companies in China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1311777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tang, W.; Li, Z. ESG systems and financial performance in industries with significant environmental impact: A comprehensive analysis. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1454822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Saeed, A.; Suleman, M.T.; Mushtaq, R. Revisiting the Association between Environmental Performance and Financial Performance: Does the Level of Environmental Orientation Matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Song, Y.; Song, P. How ESG performance impacts corporate financial performance: A DuPont analysis approach. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.; Khalil, S.; Sinliamthong, P. From ratings to resilience: The role and implications of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance in corporate solvency. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartia, U.; Panda, A.K.; Hegde, A.; Nanda, S. Environmental, social and governance aspects and financial performance: A symbiotic relationship in Indian manufacturing. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2024, 7, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wen, J.; Li, W.; He, Y. Strategic alliances and corporate ESG performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Farooq, U.; Alam, M.M.; Dai, J. How does environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance determine investment mix? New empirical evidence from BRICS. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.S. The impact of ESG performance on the financial performance of companies: Evidence from China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share listed companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1507151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.M.H.; Chan, R.Y.; Wong, P.; Wong, T. Promoting corporate financial sustainability through ESG practices: An employee-centric perspective and the moderating role of Asian values. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 75, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ren, L. Cross-border ESG regulations and corporate compliance: The role of policy compliance willingness in shaping ESG performance. J. Asian Public Policy 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good… and does it matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Fooladi, I.; Tehranian, H. Valuation effects of corporate social responsibility. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 59, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate social responsibility on investment recommendations: Analysts’ perceptions and shifting institutional logics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the stockholder to the stakeholder: How sustainability can drive financial outperformance. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sarkis, J. Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Adopting proactive environmental strategy: The influence of stakeholders and firm size. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1072–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Wang, H. ESG and customer stability: A perspective based on external and internal supervision and reputation mechanisms. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Rathore, H.; Mangla, S.K. Stakeholder pressure for sustainability: Can ‘innovative capabilities’ explain the idiosyncratic response in the manufacturing firms? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2635–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seroka-Stolka, O. Towards sustainability: An environmental strategy choice, environmental performance, and the moderating role of stakeholder pressure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 5992–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, J.F.; Heeb, F.; Paetzold, F.; Busch, T. Can sustainable investing save the world? Reviewing the mechanisms of investor impact. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.C.; Iandolo, F.; Renzi, A.; Rey, A. Embedding sustainability in risk management: The impact of environmental, social, and governance ratings on corporate financial risk. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, D.; Vigneau, L.; Bohn, S.; Wickert, C. Institutional theory-based research on corporate social responsibility: Bringing values back in. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kadach, I.; Ormazabal, G.; Reichelstein, S. Executive compensation tied to ESG performance: International evidence. J. Account. Res. 2023, 61, 805–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ding, C.; Yue, W.; Liu, G. ESG performance and corporate risk-taking: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Luo, S. Sustainable development, ESG performance and company market value: Mediating effect of financial performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3371–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. The antecedents of deinstitutionalization. Organ. Stud. 1992, 13, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | ||||||

| EA | GHG reduction | 1 | 0.755 | 0.62 | 0.83 | ||

| Environmental impact mitigation | 1.116 | 0.861 | 0.092 | 12.07 *** | |||

| Waste management initiatives | 1.032 | 0.74 | 0.093 | 11.138 *** | |||

| SP | Local Community | 1 | 0.675 | 0.528 | 0.77 | ||

| Customers | 1.237 | 0.742 | 0.135 | 9.151 *** | |||

| Investors | 1.162 | 0.761 | 0.126 | 9.239 *** | |||

| FP | Operating profit | 1 | 0.909 | 0.853 | 0.946 | ||

| Sales revenue | 1.01 | 0.933 | 0.041 | 24.801 *** | |||

| Cash flow | 1.061 | 0.929 | 0.043 | 24.53 *** | |||

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | ||||||

| SA | Labor relations | 1 | 0.797 | 0.739 | 0.83 | ||

| Human Rights and Safety | 1.187 | 0.916 | 0.074 | 16.017 *** | |||

| Mutual Growth | 1.186 | 0.862 | 0.077 | 15.34 *** | |||

| SP | Local community | 1 | 0.614 | 0.492 | 0.77 | ||

| Customers | 1.362 | 0.788 | 0.174 | 7.83 *** | |||

| Investors | 1.212 | 0.692 | 0.156 | 7.787 *** | |||

| FP | Operating profit | 1 | 0.922 | 0.832 | 0.946 | ||

| Sales revenue | 1.005 | 0.927 | 0.041 | 24.477 *** | |||

| Cash flow | 0.99 | 0.887 | 0.045 | 22.2 *** | |||

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | ||||||

| GA | Strengthening Governance Framework | 1 | 0.81 | 0.681 | 0.864 | ||

| Ethical Management | 1.267 | 0.924 | 0.087 | 14.55 *** | |||

| Legal compliance | 1.054 | 0.73 | 0.084 | 12.49 *** | |||

| SP | Local community | 1 | 0.704 | 0.424 | 0.684 | ||

| Customers | 1.182 | 0.722 | 0.152 | 7.799 *** | |||

| Investors | 0.719 | 0.506 | 0.112 | 6.421 *** | |||

| FP | Operating profit | 1 | 0.947 | 0.766 | 0.907 | ||

| Sales revenue | 0.974 | 0.903 | 0.045 | 21.877 *** | |||

| Cash flow | 0.811 | 0.766 | 0.05 | 16.148 *** | |||

| Model | χ2 | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Criteria | Value | Criteria | Value | Criteria | ||

| E | 47.38 | 0.974 | ≥0.95 | 0.983 | ≥0.90 | 0.062 | ≤0.08 |

| S | 40.099 | 0.983 | 0.988 | 0.051 | |||

| G | 59.866 | 0.953 | 0.969 | 0.077 | |||

| Model | Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | |||||

| E | EA → FP | 0.216 | 0.307 | 0.122 | 2.524 | Rejected |

| S | SA → FP | 0.409 | 0.515 | 0.085 | 6.023 *** | Supported |

| G | GA → FP | 0.136 | 0.198 | 0.105 | 1.881 | Rejected |

| Model | Path | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| E | EA → SP → FP | 0.272 | 0.087 | 0.131~0.497 | Supported (Full) | |

| S | SA → SP → FP | 0.111 | 0.051 | 0.039~0.242 | Supported (Partially) | |

| G | GA → SP → FP | 0.302 | 0.112 | 0.140~0.566 | Supported (Full) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, A.Y.; Kim, D.; Na, J. Disaggregating ESG Mechanisms: The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Pressure in the Financial Performance of Logistics Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198840

Choi AY, Kim D, Na J. Disaggregating ESG Mechanisms: The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Pressure in the Financial Performance of Logistics Firms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198840

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, A Young, Dohyun Kim, and Joonho Na. 2025. "Disaggregating ESG Mechanisms: The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Pressure in the Financial Performance of Logistics Firms" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198840

APA StyleChoi, A. Y., Kim, D., & Na, J. (2025). Disaggregating ESG Mechanisms: The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Pressure in the Financial Performance of Logistics Firms. Sustainability, 17(19), 8840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198840