1. Introduction

The Orchidaceae family is one of the most collected epiphytic plants [

1], traded both legally and illegally worldwide as whole plants, pseudobulbs, or flowers [

2]. Used as ornamentals, medicinal plants, or even as food, the demand for wild orchids has increased in regional, national, and international markets, driven primarily by collectors and enthusiasts [

3]. In the Mexican markets, approximately 333 species of wild orchids are traded illegally, mostly epiphytes [

4].

Native orchids are commonly sold in local markets as ornamental plants, often illegally harvested from their natural habitat [

5]. The propagation of native orchids using in vitro techniques has been improved to meet market demands and reduce the pressure over natural populations [

6]. However, most orchid gatherers come from economically marginalized communities [

7] and lack the resources and knowledge needed for in vitro propagation [

4].

Community-based ecotourism has been widely recognized as a strategy that not only promotes biodiversity conservation, but also empowers local populations by ensuring that they actively participate in, and benefit from, tourism initiatives. Scheyvens [

8] introduced the “empowerment framework,” highlighting that ecotourism is successful only when local communities share equitably in its economic, social, psychological, and political benefits. Ecotourism opens new ground for anthropological research by reshaping community relations, cultural practices, and local economies through direct engagement with global tourism markets [

9]. Honey [

10] argues that while ecotourism is often promoted as a dual solution for both environmental conservation and community well-being, in practice there is wide variation in its implementation. She distinguishes between “genuine ecotourism” and diluted forms of “ecotourism lite,” emphasizing that the most successful cases are those where local communities not only receive economic benefits, but also hold decision-making power and participate directly in tourism management.

Community-based tourism (CBT) has been identified as a transformative model that directly contributes to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, by generating local employment, supporting entrepreneurship, and fostering sustainable livelihoods. Case studies from regions such as Nepal, Kenya, Costa Rica, and Zimbabwe illustrate how CBT strengthens community resilience and reduces poverty by ensuring that tourism revenues remain within local economies [

11]. Sustainable resource management is essential to reduce environmental pressures and to align local practices with global sustainability goals. Raman et al. [

12] argue that strategies such as minimizing waste and promoting circular practices can directly support biodiversity conservation and community well-being, making SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) a crucial reference point for studies addressing the use and commercialization of natural resources.

Ecotourism initiatives can play a direct role in advancing SDG 15 (Life on Land) by linking biodiversity conservation with local development goals. Castillo-Salazar et al. [

13] show that in mountain regions such as Sobrarbe (Spain), innovative governance models have simultaneously strengthened ecosystem protection, created local employment, and enhanced community participation in conservation efforts.

Ecotourism is recognized as a mechanism for biodiversity conservation and livelihood support in regions where rural communities depend on natural resources. Samal and Dash [

14] emphasize that community-based ecotourism (CBET) operates as a “coexistence model” capable of aligning ecological protection with poverty alleviation by empowering local actors, reducing extractive pressures, and enhancing governance structures.

Orchids offer diverse opportunities for tourism activities, from large-scale events showcasing numerous species [

15,

16] to interpretive trails through cloud forests, allowing visitors to observe orchids in their natural environment [

17]. Domestic and international tourists are interested in discovering native orchids and their natural habitats [

18].

Orchid tourism trails are pathways where the educational process can be facilitated by observing and explaining the diversity of epiphytic orchids, whether focusing on individual species or their ecological roles [

19,

20,

21]. Additionally, orchid collections can serve as refuges for endangered species [

22] and as centers for reproduction and research [

23]. Recent evidence shows that there is a strong and growing demand for orchid-based tourism in central Veracruz; Hernández-García et al. [

16] found that more than 90% of orchid enthusiasts surveyed during the International Orchid Festival expressed interest in visiting rural communities to learn about native orchids, with species such as

Laelia anceps,

Myrmecophila grandiflora, and

Trichocentrum stramineum identified as the most attractive to tourists. This study suggests that orchid tourism not only has ecological and cultural value, but also represents a profitable market segment for local communities.

While there are studies on the illegal trade of orchids in local markets [

5,

7,

24,

25,

26], many overlook the role of nursery owners, collectors, and companies involved in native orchid trade and their potential as a resource for tourism.

This study analyzes the informal trade network of native orchids in central Veracruz to identify conservation and economic transition opportunities. Specifically, the study examines: (1) the diversity and conservation status of traded species; (2) trade across different actor types and sale points; and (3) the potential of key actors to engage in orchid-based tourism as a sustainable alternative to wild harvesting.

The hypothesis was that integrating local orchid trade with community-based tourism can support biodiversity conservation and sustainable livelihoods, as suggested by the interest of local actors and the identified species with touristic and commercial value in central Veracruz.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in central Veracruz, Mexico, a region characterized by high native orchid diversity and a significant informal market for orchid trade. The study was carried out in local nurseries, private collections, local markets and tianguis (weekly, open-air street markets traditionally held on a particular day of the week), which serve as primary commercialization hubs where orchids from surrounding forests and nurseries enter the trade network [

7,

24].

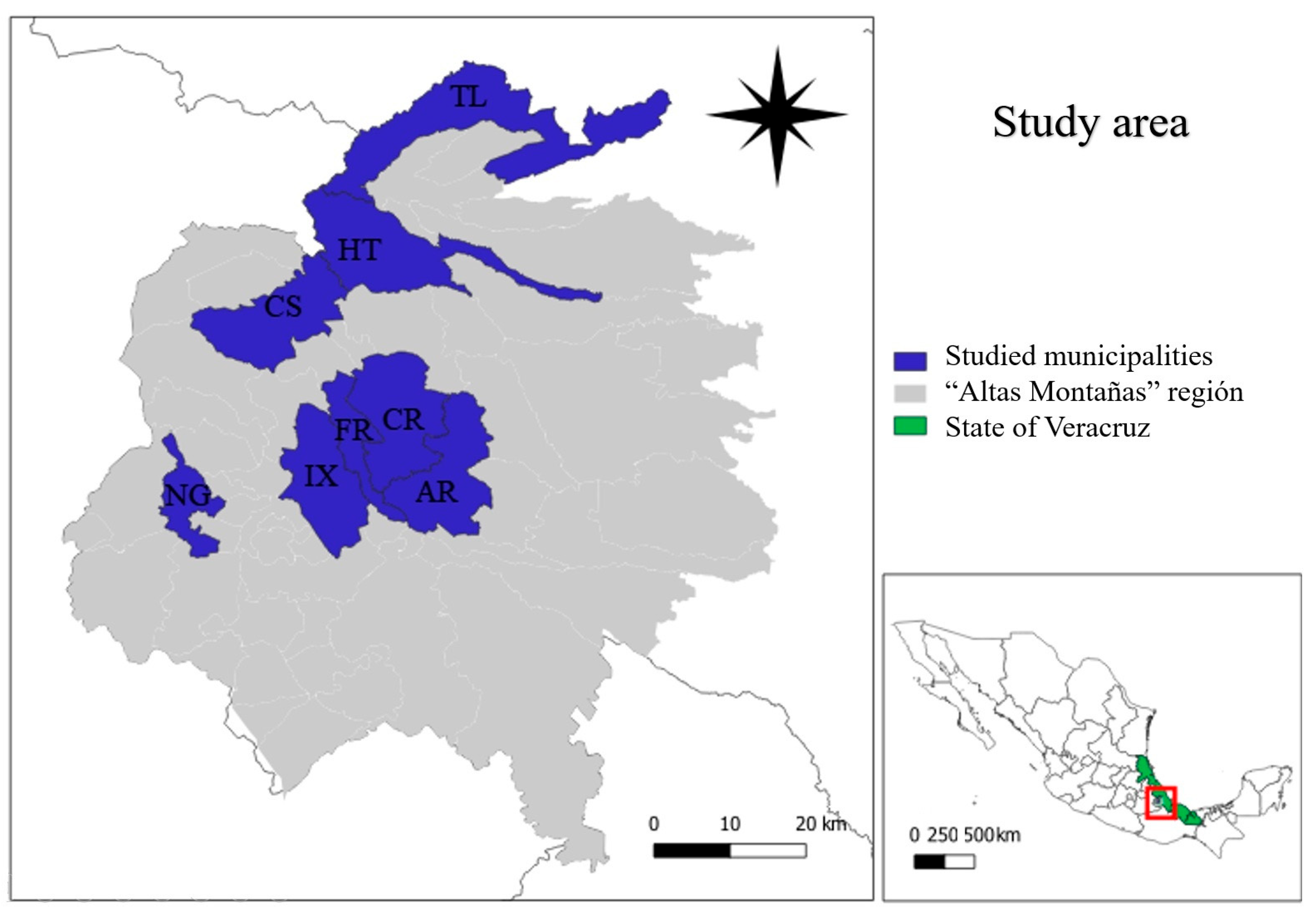

The study encompassed eight municipalities: Amatlán de los Reyes, Córdoba, Coscomatepec, Fortín, Huatusco, Ixtaczoquitlán, Nogales, and Tlaltetela (

Figure 1), where orchid collection, propagation, and sales contribute to the broader trade dynamics. The region’s humid subtropical climate and elevations ranging from 800 to 1500 m above sea level provide optimal conditions for wild orchid growth, making it an ideal site for examining trade flows, conservation concerns, and alternative economic strategies [

5,

26].

The methodological design aimed to characterize trade actors, assess conservation risks, examine trade patterns and pricing structures, and explore the potential of orchid-based ecotourism as a sustainable alternative [

4]. This research followed a qualitative method design. The qualitative component consisted of 17 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders identified through a snowball sampling strategy, which is widely used to access hard-to-reach populations and informal markets [

27,

28]. The limited number of interviews reflects the difficulty of accessing actors involved in orchid commercialization; therefore, the results emphasize the depth of perceptions and practices rather than statistical representativeness.

The survey was designed to understand the use of native orchids in the region. The unit of analysis was orchid vendors and producers, who were asked to identify other individuals involved in orchid collection or trade.

The survey included 49 open-ended and multiple-choice questions. It gathered general information about the respondents (e.g., gender, age, place of residence, education level, and occupation), the species of orchids they trade, their knowledge of these species, and their willingness to develop tourism activities in their communities.

Interviews were conducted with orchid vendors in local markets across the eight municipalities between January and December 2023. Additionally, individuals who collect and cultivate native orchids in their backyards, nurseries, or specialized enterprises were interviewed. Photographic evidence of orchids was taken with the prior consent of participants. Species identification was based on illustrated guides and the literature focusing on the region’s orchids [

29,

30,

31].

The qualitative analysis followed the inductive content analysis approach described by Elo & Kyngäs [

32]. After transcription, interview data were reviewed to ensure quality and pertinence, excluding incomplete or off-topic responses. The curated transcripts were then organized into Excel spreadsheets, where open coding was applied. Codes were generated inductively from the raw data, with similar codes grouped into categories and progressively abstracted into broader themes. This iterative process allowed the themes to emerge directly from participants’ narratives, ensuring that the findings remained grounded in the empirical material while capturing the complexity of perceptions across municipalities.

The average age of the respondents was 48 years, and their average level of education was 8 years. Four types of actors involved in the use of native orchids were identified and categorized based on their characteristics: gatherers, nurserymen, collectors, and private companies (

Table 1,

Figure 2a–d).

Ethical Considerations

Before initiating each interview, participants were provided with a clear verbal explanation of the purpose of the study, the type of information that would be collected, and how their responses would be used. Participants were explicitly informed that their involvement was voluntary, that they could withdraw at any point without consequences, and that their anonymity and confidentiality would be maintained throughout the research process and in any resulting publications. No personal identifiers or sensitive data that could lead to their identification were collected or recorded. Verbal informed consent was obtained and noted by the lead researcher for each participant, following the ethical guidelines outlined in the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE) Code of Ethics [

33].

A limitation of this study is its small sample size, consisting of seventeen interviewees representing four key actor groups: gatherers, nurserymen, collectors, and companies. While limited in number, the diversity of actors interviewed provides a representative overview of market structures [

26].

3. Results

3.1. Wild Orchid Commercialization

The orchid trade in central Veracruz operates through a structured network of gatherers, nurserymen, collectors, and companies, each playing a distinct role in sourcing, propagating, and distributing native orchids. Across markets, nurseries, and private collections, 51 species from 18 genera were identified, with 31 species actively traded. Of the 31 traded species, 10 were listed under a conservation risk category in NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 [

34]. The most frequently encountered species were

Laelia anceps Lindl.,

Prosthechea cochleata (L.) W.E. Higgins and

Epidendrum radicans Pav. ex Lindl. Orchids were mainly sold in local markets and directly in the producers’ nurseries, but sales were also recorded at fairs and through the internet (

Table 2).

3.2. Key Actors, Their Knowledge of Orchids, and Relationship to Sale Prices

The trade network revealed distinct commercialization patterns among different actors: Gatherers were primarily present in local markets across Córdoba, Coscomatepec, Fortín, and Huatusco, where they sold orchids obtained through forest collection or intermediaries. This group was the largest, comprising 22 individuals who sell native orchids in local markets in the municipalities of Córdoba, Coscomatepec, Fortín de las Flores, and Huatusco. However, only five of these individuals agreed to participate in the study. This group primarily harvests wild orchids from forests in the region and even from neighboring states. The orchids sold by these actors were mainly divisions of adult plants with three or four pseudobulbs, sold at relatively low prices in local markets. This group was the most economically dependent on orchid sales. Many depended on orchid sales as a significant part of their household income and had limited knowledge of species identification or propagation techniques.

Nurserymen engaged in small-scale cultivation and distributed their plants through local markets, direct sales, and online platforms, with prices higher than those offered by gatherers. They maintain and reproduce native orchid species, along with other ornamental species, in backyard cultivation spaces. This group was primarily composed of homemakers and farmers who used native orchids as a supplementary source of income. Their operations involved moderate propagation techniques, and they reinvested earnings into their nurseries.

Collectors maintained private collections for personal use and occasionally exchanged or sold plants. This group exhibited the greatest diversity of orchids and the highest level of knowledge about the species they cultivated. While they do not primarily engage in orchid sales, they occasionally exchange or sell propagules to other collectors. For these individuals, orchid cultivation was a hobby and was even considered therapeutic. Orchids in collectors’ care were generally in good condition, with some even naturally producing fruit. For instance, in two collections visited during this study, 43 native orchid species were identified, a high number considering the limited cases studied.

Companies operated at a larger scale, primarily offering hybrids and exotic species while maintaining some native species in their production cycles. These businesses focused on formal sales channels, such as retail stores and fairs, and demonstrated the highest degree of technical expertise in propagation and commercial production. While these companies reproduced some native orchid species, their main source of income was the sale of exotic orchid species and hybrids. The orchids they sold commanded the highest prices compared to the other groups.

The majority of these orchids were acquired through informal channels, with only two respondents possessed legal permits for species classified under NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 [

34]. On average, 48% of the income of local market vendors came from selling orchids. While companies and some nurserymen cultivated a mix of native and hybrid species, gatherers primarily relied on wild-collected orchids, which they acquired directly from forests or through intermediaries.

Market prices varied significantly, ranging from $25.00 to $600.00 MXN ($1.25 to $30.00 USD) per plant. Species rarity, cultivation effort, and vendor type influenced pricing. Collectors and nurserymen commanded higher prices, as their orchids were better maintained, while gatherers set lower prices, prioritizing volume over exclusivity.

The findings show that differences in actors’ knowledge influenced commercialization practices and openness to alternative livelihood pathways. Nurserymen and collectors with greater taxonomic knowledge and cultivation skills established differentiated pricing schemes, often assigning higher values to endemic or culturally significant orchids. In contrast, gatherers with limited knowledge applied uniform prices and expressed little interest in ecotourism, reflecting their stronger dependence on immediate sales. These patterns indicate that knowledge functions not only as a practical resource for pricing, but also as a factor shaping the degree of engagement with alternative commercialization strategies.

Despite variations in trade practices, conservation concerns were widespread among all groups. Respondents noted the increasing scarcity of Stanhopea tigrina Bateman ex Lindl. and Acineta barkerii Bateman (Lindl.), which had been heavily harvested for regional and national markets. However, economic constraints and the absence of structured support for legal cultivation limited the ability of gatherers and nurserymen to transition toward sustainable practices. Euchile karwinskii (Mart.) Christenson, Lycaste aromatica (Graham) Lindl., Prosthechea radiata (Lindl.) W.E. Higgins and Stanhopea tigrina are highly demanded for their fragrance.

The market flow analysis indicated that orchids followed distinct commercialization pathways,

Figure 3 illustrates the flow of orchids from forests to markets, highlighting the roles of different actors in the trade network. Native orchids are mostly extracted from forest by gatherers, who often live in communities surrounded by natural areas. They sell their plants mostly at local markets and fairs. Nurserymen and collectors sometimes sourced their plants from wild populations, but mostly by third-party suppliers. Collectors are the group with most interactions with other actors and salle points. Companies relied on propagation of plants bought from other actors. Although direct-to-consumer sales occurred at nurseries and specialized fairs, most orchids passed through multiple intermediaries, highlighting the fragmented nature of the supply chain.

The results also revealed that some actors considered orchid-based tourism as a complementary activity to trade, with potential to diversify income while reducing pressure on wild populations. Nurserymen and collectors were more inclined to explore this alternative, while companies emphasized hybrid production for commercial purposes, showing only moderate interest in tourism. These findings illustrate the interaction between knowledge, market behavior, and willingness to engage in tourism, suggesting that actors’ roles in commercialization are closely linked to their potential participation in productive conservation initiatives.

Most participants recognized the potential benefits of reducing reliance on wild collection while expanding market opportunities. However, barriers such as inadequate infrastructure, limited financial support, and the need for specialized training in tourism management were cited as significant challenges. Nurserymen and collectors expressed the highest level of interest in developing tourism-based activities, given their existing orchid collections and knowledge of native landscape.

The findings suggest that economic necessity, market demand, and regulatory limitations shape the orchid trade in central Veracruz. While conservation awareness is high, the lack of structured support for legal propagation and sustainable trade models constrains efforts to transition away from informal harvesting. Strengthening financial incentives, expanding access to technical training, and integrating orchids into ecotourism initiatives could provide viable pathways for reducing pressure on wild populations while ensuring economic sustainability for those involved in trade.

4. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the complexity of the orchid trade in central Veracruz, where a diverse network of actors participates in the commercialization of native species under varying degrees of formality. The persistence of informal trade, as observed in other regions with high orchid diversity, is linked to the absence of viable alternatives for small-scale vendors and limited accessibility of legal propagation programs [

7,

24]. Similar patterns of ornamental wild plant commercialization have been observed in other Mexican markets, such as Tenancingo and Jamaica, where a high diversity of native species is sold without formal regulation [

35]. This study’s broader actor composition distinguishes central Veracruz from other regions where orchid trade is dominated almost exclusively by gatherers, highlighting the relevance of including nurserymen and collectors in conservation-oriented strategies.

The diversity of orchids found in this study is average compared to the number of species identified in other studies [

5,

25,

36]. On one hand, these studies were conducted in Chiapas, the state with the greatest orchid diversity with 717 species [

29], and the State of Mexico, which hosts 202 species [

37]. Unlike Chiapas, where orchid trade is heavily concentrated in local markets, central Veracruz exhibits a more diverse trade network involving nurseries, collectors, and companies. This diversity presents both challenges and opportunities for conservation, as it allows for a broader range of stakeholders to engage in sustainable practices. Orchid-based tourism can contribute directly to conservation by diversifying the income sources of harvesting communities, thereby reducing pressure on wild populations. Successful models in Indonesia [

19] and Costa Rica [

23] have shown that interpretive trails and living collections can replace illegal extraction by generating comparable income through guided tours, the sale of legally propagated plants, and tourism services. This approach transforms informal trade actors into conservation allies.

More than 60% (31) of the identified orchid species were commercially available, while the remaining 20 were either too rare to be sold or part of private collections. In Chiapas, Jiménez-López et al. [

5] reported 60 orchid species traded in a single market in Las Margaritas, with four species classified under conservation risk categories [

34]. Emeterio-Lara et al. [

25] identified six orchid species in southern Mexico State, but the collection intensity and number of illegal traders were higher compared to other states.

The most frequently traded species was

Laelia anceps, in Mexico, the genus

Laelia holds significant cultural importance, with species like

Laelia autumnalis (Lex.) Lindl. 1831 used in rituals and offerings, particularly during Día de Muertos, a tradition dating back to pre-Hispanic times [

25].

Offered prices were higher than those reported in other studies. For instance, Emeterio-Lara et al. [

25] documented prices ranging from

$5 to

$80 MXN per individual. Similarly, Jiménez-López et al. [

5] recorded prices between

$5 and

$100 MXN. These price differences may reflect varying levels of knowledge among gatherers about the species they sell. For example,

Laelia anceps subsp.

dawsonii var. alba, a rare white variant, can sell for more than

$500 MXN in both this study and the work of Flores-Palacios and Valencia-Díaz [

24].

Gatherers prioritized volume sales, offering plants at lower prices to attract more buyers. These findings align with broader studies on plant trade, where price is often dictated by knowledge asymmetry and access to cultivation resources rather than strict legal regulations [

2,

5]. The persistence of illegal orchid trade is closely linked to economic hardship in rural communities, where orchids represent a quick source of income with no upfront investment. Addressing this issue requires structural interventions, including support for legal production, subsidies for certification, access to fair markets, and environmental education initiatives that promote the role of producers as stewards of biodiversity [

4,

38].

Most studies on orchid sales focus on local markets [

5,

7,

24,

25], others emphasize online sales [

26]. Flores-Palacios and Valencia-Díaz [

24] highlighted the importance of studying nurseries for a more comprehensive understanding, as previous studies largely overlooked this aspect. Additionally, fairs, which serve as significant trade points, remain underexplored.

The implications of this study also extend to the design of public policies that could support a transition toward sustainable orchid use. Although, numerous policies and regulations on orchid conservation have been issued, there remain substantial gaps between in situ and ex situ measures, and a lack of consistency in regulatory enforcement across countries [

39]. Previous work has shown that one of the main gaps in orchid trade is the lack of fair benefit-sharing and weak institutional capacity in producing countries [

40]. In this sense, a stronger role of national and local governments is needed to establish monitoring systems and provide technical and financial assistance for producers who are willing to shift from extractive practices to legal and sustainable activities.

Certification schemes represent another key strategy. As highlighted by Hernández-Mejía et al. [

41], orchids provide not only cultural, but also provisioning and supporting ecosystem services that are rarely recognized in economic terms. Certification programs that integrate these ecological and cultural values could increase market transparency and allow consumers to identify products and tourism experiences that contribute directly to conservation.

Finally, the financial dimension cannot be ignored. Studies in Southeast Asia and Latin America show that orchids generate significant revenues through horticulture and ecotourism, but the benefits are unevenly distributed [

40,

41]. Mechanisms such as payment for ecosystem services, targeted subsidies, and microcredits for community enterprises could help local actors cover initial investments and reduce their dependence on illegal extraction. Linking financial incentives with certified sustainable practices would create a virtuous circle between conservation, tourism development, and rural livelihoods.

These findings emphasize the need for prioritizing the conservation and reproduction of these species. Prior studies have shown that trade restrictions alone are insufficient to curb the unsustainable harvest of wild orchids, especially when enforcement is weak and legal alternatives are underdeveloped [

26,

38]. Conservation programs that integrate community knowledge, especially in areas with high orchid endemism, show higher success rates. Rather than imposing top-down restrictions, these initiatives empower local actors, who often possess deep ecological understanding and traditional knowledge of native orchid species [

36].

Strengthening propagation initiatives and integrating local trade actors into conservation programs could mitigate these pressures while ensuring economic viability for vendors. To maximize impact, conservation strategies should be multi-layered: combining physiological advances in orchid cultivation, such as in vitro flowering which cuts juvenility periods, allowing orchid plants to enter the market at a younger age [

42]. Government agencies could establish certification programs for legally cultivated orchids, providing financial incentives for nurserymen and collectors to transition away from wild harvesting. Additionally, local communities could be supported through training programs in sustainable orchid cultivation and ecotourism management, fostering long-term conservation efforts.

Orchid collectors maintain a high number of species, some of them considered rare or endangered. Collections can act as reservoirs for rare and hard-to-reproduce species, underscoring the importance of linking conservation institutions with private collectors [

43]. Large collections also enable year-round blooming cycles [

23]. Orchids under the care of nursery owners, collectors, and companies exhibited signs of proper care, with many plants healthy enough to produce fruit through natural pollination. This highlights the potential for these actors to play a key role in sustainable conservation practices.

Some respondents owned cultivation lands that could support ecotourism activities such as hiking, given their proximity to conserved sites. Communities demonstrated knowledge of locations suitable for tourism activities. Baltazar-Bernal [

20] proposed leveraging native orchids through the creation of tourism trails to promote the preservation of nature and orchid culture. Participants expressed interest in tourism and orchid conservation, though their primary motivation for these projects was economic, viewing tourism as an opportunity to generate higher income. Tourism has the potential to positively impact orchid conservation and their ecosystems while providing economic benefits to local communities [

18].

In comparative perspective, several international cases illustrate how orchid-based tourism can evolve beyond descriptive inventories into structured strategies for sustainable development. For instance, in Ecuador, Guevara-Rosero et al. [

44] describe the design of a thematic orchid route in Carchi province as a community-based ecotourism initiative that diversifies local economies while fostering conservation practices. Similarly, Echeverri et al. [

45] emphasize in Colombia that integrating biocultural richness into ecotourism planning highlights the importance of linking biodiversity with cultural heritage, showing that sustainable tourism must account for both ecological and socio-cultural dimensions. Beyond Latin America, Widodo et al. [

46] demonstrate that orchid-centered ecotourism in Karunia Village, Lore Lindu National Park, Indonesia, achieved a feasibility level of 78.5%, supported by adequate infrastructure and local partnerships for conservation, proving its potential as a viable rural development model. These cases suggest that orchid-based tourism can serve as a catalyst for conservation, cultural valorization, and economic inclusion when supported by coherent strategies and local participation.

Therefore, it is essential to encourage communities to organize and collaborate for the development of local tourism projects. A viable strategy would be the establishment of community nurseries with institutional support, where gatherers can receive training and access basic inputs (such as culture media and shading structures) in exchange for verifiable commitments not to extract protected species. Such productive conservation agreements have been successful in other regions with high-value forest resources [

6].

5. Conclusions

The wild orchid trade in central Veracruz is shaped by a structured yet informal network of gatherers, nurserymen, collectors, and companies, each contributing to several aspects of commercialization. Central Veracruz’s diverse trade network offers unique opportunities for integrating conservation and sustainable development. Nevertheless, economic dependence on orchid sales and the absence of structured support for legal propagation reinforce reliance on wild-collected plants. Enforcement of trade regulations remains limited, and economic constraints prevent many vendors from transitioning toward sustainable cultivation.

The willingness of certain actors to engage in orchid-based tourism highlights the intersection between cultural capital, market value, and conservation opportunities. This analytical perspective suggests that promoting sustainable orchid use requires not only regulatory interventions, but also strategies that recognize and build upon existing knowledge and practices at the community level.

The findings highlight the need for practical interventions that can strengthen the transition toward sustainable orchid use. Training programs in taxonomy, cultivation, and ecotourism practices could expand the capacity of local actors, particularly gatherers, to engage in productive conservation. This would increase consumer trust and market value, while financial incentives and technical support for nurserymen and knowledgeable collectors could accelerate their role as leaders in sustainable practices. Developing integrated conservation policies for sustainable orchid trade could reduce reliance on wild collection while ensuring economic stability for those engaged in the trade. Strengthening collaborations between government agencies, conservation organizations, and local vendors will be key in ensuring the long-term viability of orchids in both ecological and commercial contexts. Community-led orchid tourism could serve as a replicable model for other biodiversity-rich regions facing similar conservation and livelihood challenges.

By generating alternative income sources and strengthening local capacities, orchid tourism aligns with SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth). The implementation of sustainable commercialization practices and certification schemes directly supports SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production). Moreover, the integration of orchid trade with conservation strategies addresses SDG 15 (Life on land) by reducing extractive pressures and fostering biodiversity protection. Framing the findings within the SDG underscores the of orchid-based tourism as a model for productive conservation.

This study points to several strategies for transitioning toward sustainable practices. First, ex situ propagation and nursery-based production of native orchids can reduce dependence on wild harvesting, while supplying both local markets and ecotourism initiatives. Second, alliances between nurserymen, community groups, and tourism operators could foster integrated orchid routes that generate income and awareness simultaneously. Finally, embedding orchid trade within conservation policies would align local practices with broader sustainability goals. Together, these strategies provide a pathway for transforming orchid commercialization into a driver of productive conservation.