1. Introduction

Uneven development of countries creates significant distortions in the world economy, generating constant economic, social, and political threats. Back in 2000, the UN adopted the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [

1] to overcome global poverty, hunger, inequality, and improve health, education, and access to basic services. The need arose due to the deepening socioeconomic crises after the Cold War and the need for a single global action plan for developing countries. The report on the implementation of the MDGs [

2] was quite optimistic: it stated that significant progress had been made in reducing poverty (from 1.9 billion to 836 million people), access to drinking water (achieved by 90%), and education (increased coverage to 91%), but the goals on hunger, HIV/AIDS, and maternal mortality were not fully met. In general, the goals were not achieved.

In 2015, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution 70/1, “Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” [

3] with 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which included ending poverty, ending hunger, achieving good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, clean water and adequate sanitation, affordable and clean energy, decent work and economic growth, industrialisation, innovation and infrastructure, reducing inequalities, sustainable cities and communities, responsible consumption and production, combating climate change, conserving marine ecosystems, conserving terrestrial ecosystems, peace, justice and strong institutions, and partnerships for sustainable development.

Despite the unanimous adoption of such goals, over the past decade, the world has made relatively little progress towards achieving these goals [

4]. According to the UN report for 2024, only 17% of the SDGs are expected to be achieved by 2030. The main problems arise from wars, economic instability, and discussions on understanding the concept of the climate crisis. Even the basic goals are clearly unattainable in some countries. In particular, since 2019, 23 million additional people have fallen into extreme poverty due to COVID-19, wars and economic crises, while 100 million additional people are malnourished, and obesity rates have worsened in most countries. Although under-5 mortality has decreased, life expectancy has decreased due to the pandemic and conflicts. Access to primary education has increased, but in West Asia and North Africa, the number of children out of school has increased due to conflicts. In 2024, no country had achieved gender equality, with a third of countries having made no progress since 2015, and the situation for women had even worsened in 18 countries, such as Venezuela, Afghanistan, and South Africa. At the current rate of progress, it will take at least another 131 years to achieve gender equality worldwide [

5]. Access to drinking water has increased, but 2.2 billion people are still without safe water. Population access to electricity has increased, but 675 million people remain without electricity, and the share of renewable energy does not meet targets. Unemployment has increased due to economic crises, and informal employment remains high. Global inequality between and within countries has increased. Vulnerable groups (migrants, people with disabilities) are being neglected. Urbanisation in poor countries is outpacing infrastructure development. Excessive resource consumption and waste are increasing. Globally, CO

2 emissions are rising because countries are failing to meet their Paris Agreement commitments. Overfishing and ocean pollution are damaging marine ecosystems. Press freedom has deteriorated, the number of displaced people has increased to 120 million (2024), and civilian casualties from conflicts have increased by 72%. SDG funding is insufficient. International cooperation is weakening due to geopolitical conflicts.

In general, we can state the complete failure of all SDGs in most countries of the world. A natural question arises: why do countries that voted for such goals systematically fail to fulfil them? This paper attempts to answer this question from the perspective of geopolitical, economic, and technological changes taking place in the world. Our study makes a novel contribution by systematically linking three structural global trends—trade stagnation, regionalisation of economies, and automation of labour markets—to the achievement of the SDGs. Unlike previous works, which typically focus on one dimension (e.g., economic growth, climate change, or governance), we provide an integrated analysis covering 2005–2024. This broader scope allows us to capture long-term dynamics, including post-pandemic developments, and to highlight the combined effects of economic, geopolitical, and technological barriers. Thus, the study fills an important gap in the literature by showing how these interrelated processes jointly hinder the fulfilment of the SDGs.

One reason is the so-called middle-income trap, a situation where countries that have reached middle-income status are unable to make the transition to high-income status. In particular, out of 108 middle-income countries, only 34 have managed to move into the high-income category over the past 30 years [

6]. The development of middle-income countries is characterised by three main strategic phases. At the initial stage, countries focus on capital accumulation through investments in infrastructure, education, and capital investment. At the next stage, the emphasis shifts to the introduction and diffusion of foreign technologies, which contribute to economic growth. To achieve a high level of income, countries must move to creating their own innovations, since simply copying foreign technologies becomes insufficient. However, the growth of middle-income countries is slowing down due to a number of factors: the exhaustion of the effect of capital accumulation, demographic ageing, increasing debt burdens, global trade conflicts, protectionism, and the need for expensive reforms for the “green transition”. According to World Bank experts, the key to overcoming these challenges lies in the triad of economic development: creation, preservation, and destruction. Creation involves the emergence of new enterprises and ideas that stimulate progress. Conservation, however, can hinder development, as governments and large companies often protect their privileges by blocking change. The destruction of outdated structures, such as monopolies, state-owned enterprises or “brown” energy, is necessary to free up space for new solutions and ensure sustainable economic growth.

Another reason is the change in the economic paradigm of the world. If countries previously expected to gain economic benefits from the strengthening of globalisation processes and from participation in the international division of labour, today the world is faced with trade wars, tariffs, and other restrictions. Since 2015, the Globalisation Index [

7] has practically not changed, while in the period from 2000 to 2015 it increased by 14%. This shows significant problems in globalisation processes and in the desire of countries to build a common world economy. It is not for nothing that more and more economists put forward the idea that the world expects regionalisation instead of globalisation [

8].

The aim of this article is to identify the reasons for the slowdown in the achievement of the SDGs in the world, and the economic and geopolitical prerequisites of these processes. This study fills a gap in the literature by comprehensively analysing geopolitical, economic, and technological barriers to the SDGs, focusing on the interrelationships between global trade stagnation, regionalisation of economies, and the impact of automation on the labour market. Unlike previous studies, we used data from 2005–2024 to quantitatively analyse trends across countries at different income levels, allowing us to identify new patterns and offer targeted recommendations.

2. Literature Review

The literature review aims to systematise current research on the obstacles to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), focusing on the economic, geopolitical, and technological factors that influence their implementation. In this section, we review key works that analyse the impact of economic growth, global crises, trade regionalisation, and automation on progress in achieving the SDGs. The review is structured according to thematic blocks: economic barriers, geopolitical risks, and the impact of the digital economy and automation, as well as limitations of previous research. This identified gaps in the literature and justified the need for a comprehensive analysis of the relationships between these factors, which was the basis of our study.

2.1. Post-Pandemic World

The problem of implementing and achieving the SDGs in the world is actively discussed among scientists. Official UN reports claim that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, progress on the SDGs was uneven: there was a significant reduction in extreme poverty (SDG 1), but slow progress in combating climate change (SDG 13) and inequality (SDG 10). By 2020, 71 million people had returned to extreme poverty due to the pandemic, which slowed down SDG 1. Progress on SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) was halted due to disruptions in supply chains. At the same time, sub-Saharan Africa lagged the most (80% of the population in extreme poverty) behind the rest of the world [

9].

Some authors [

10] demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened progress on most of the SDGs, especially in the areas of education, health, and the economy. Different countries have faced increased interactions between the SDGs, where positive linkages have weakened and negative trade-offs have increased. The authors emphasise the need to strengthen policy complementarity between the goals.

These results are confirmed by the authors of [

11], who acknowledge moderate global progress on most indicators, although none of them meet the 2030 targets. Deterioration is observed in the areas of food security, nutrition, malaria incidence, road traffic mortality, and greenhouse gas emissions. A comparative analysis of the pace of progress before and after 2015 indicates accelerating improvements in HIV incidence, and access to antiretroviral treatment and electricity, while other indicators show slowing progress or no significant change. Long-term trends suggest that gaps in SDG implementation existed even before the crises of the 2020s. Country-level analysis does not reveal a uniform pattern of progress: even the poorest countries show acceleration on some indicators, but no country achieves accelerated progress on all.

2.2. Economic Barriers

N. Eisenmenger et al. showed [

12] that the emphasis on economic growth determines the priority of relative indicators over absolute reduction of resource consumption. The authors note that only a few industrialised countries (e.g., Japan, the Netherlands) have been able to achieve an absolute reduction of material consumption. At the same time, relative indicators mask the true ecological load of systems. The authors of examine the economic barriers to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through a socio-ecological perspective, with an emphasis on prioritising economic growth over sustainable resource use. The main economic barrier identified in the paper is the inherent contradiction between the SDGs that promote economic growth (in particular, SDG 8—Decent Work and Economic Growth) and the goals aimed at environmental sustainability, such as SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). The authors argue that the focus of the SDGs on economic growth reinforces unsustainable resource use, as GDP growth is often correlated with increased consumption of natural resources and emissions, making it difficult to achieve environmental goals. An additional barrier is the dependence on existing institutional structures that support economic models that are oriented towards growth rather than transformation towards sustainable development. The authors recommend a review of approaches to the SDGs to balance economic priorities with environmental sustainability, including through strengthened policies to reduce resource consumption.

The authors of [

13] analyse the impact of poverty as a central barrier to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing countries, based on an international survey of experts from 34 countries. The results show that 98% of respondents consider poverty to be a significant threat to the implementation of the SDGs, particularly affecting SDG 2 (No Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). The findings highlight the need to strengthen efforts to address poverty to ensure progress on other goals, emphasising the need for comprehensive strategies, including improving access to education, health, and basic infrastructure. It is recommended to develop targeted programs to reduce poverty through integration into national governance policies. Limitations of the study include reliance on subjective assessments of respondents and insufficient analysis of specific regional contexts, which may limit the generalizability of the results to countries with different socioeconomic conditions.

The authors of [

14] used modelling that predicts the achievement of the SDGs by 2030 at 20%. While northern Europe has the highest progress (85% of SDG indicators 4, 8, 9), Africa has the lowest: for example, only 5% progress in SDG 2 due to low agricultural productivity. The authors consider the main reasons for non-fulfilment to be a lack of investment, demographic pressure, and climate change. Approximately the same results were obtained in [

15], where the basis for non-fulfilment of the SDGs is indicated as conflicts between goals (for example, economic growth vs. environmental protection) and limited resources.

2.3. Geopolitical Risks

The authors of [

16] examine how geopolitical risks impact sustainable development, focusing on economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Economic growth is identified as a driver of Sustainable Development Goal 8, but may conflict with Sustainable Development Goal 13 due to increased carbon emissions, which requires the implementation of green technologies. Different military conflicts worldwide have reduced international cooperation, which has an impact on Sustainable Development Goal 17. Geopolitical risks also impact economic stability, hindering the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 1 and Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger).

The authors of [

17] examine the interaction between sustainable economic development, geopolitical risks, and energy trilemma policies (energy security, equity, and sustainable development) using a vector autoregressive model with regime change. The authors show that energy trilemma policies (e.g., clean energy investments) have a positive impact on Sustainable Development Goal 8 by stabilising energy prices and attracting investment, although the effect depends on the economic regime. Geopolitical risks increase energy price volatility, negatively affecting Sustainable Development Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and Sustainable Development Goal 13. The study suggests policies to reduce dependence on imported energy.

The authors of [

18] analyse the relationship between the Financial Development Index (FDI), the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), in the E3 countries (Germany, France, United Kingdom) over the period 2000–2021 using ARDL and DCC models. The results show that in Germany, financial development has a positive impact on both goals, while geopolitical risks have a negative impact; economic growth contributes more strongly to SDG 13. In France, FDI has a positive impact on SDG 13 but not on SDG 7, where the effects of GPR and economic growth are insignificant. In the UK, no significant long-term relationships were found, but short-term effects of FDI and GPR are notable for SDG 7. Limitations of the study include the focus on only three developed countries, which limits generalizability to developing countries, and the lack of analysis of the impact of technological change on the SDGs.

S. Pizzi et. al. in [

19] examine how international businesses contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through corporate reporting, analysing factors such as economic growth and governance structures. Economic growth allows businesses to invest in SDG-related initiatives (e.g., SDG 8, SDG 9), but only if supported by strong governance and stakeholder pressure. Geopolitical instability can reduce corporate investment in sustainable development, affecting SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 17.

The author of [

20] provides evidence that public investment has a much greater impact on the implementation of the SDGs in developing countries than private investment. The analysis shows a direct link between the volume of investment and progress on infrastructure, and social and environmental goals. The author insists on the need to expand public financial support, recognising the geopolitical nature of the level of investment.

FDI can be a powerful tool for achieving the SDGs, but its effectiveness depends on the quality of investment, the regulatory environment, and the level of institutional capacity. The authors of [

21] cover 34 European countries (2007–2022), showing that in developed countries, FDI strengthens institutional capital and technology, but does not always translate into sustainable outcomes. In developing countries, the positive impact of FDI on the SDGs is through human and institutional development, although it is limited. The authors call for individualised strategies that combine FDI with national sustainable development goals.

2.4. Digitalisation and Technology Advances

The authors of [

22] analyse the role of the digital economy in the sustainable development of 17 developed and 13 developing countries from 1990 to 2022, taking into account geopolitical risks. The authors show that the digital economy contributes to environmental (SDG 13) and socioeconomic (SDG 8) development by improving resource efficiency and access to services, particularly in developed countries. At the same time, geopolitical tensions disrupt global supply chains and technology transfer, negatively impacting Sustainable Development Goals 9 and 17. The study highlights the need for resilient digital infrastructure to counter these risks. U. Gupta et al. [

23] emphasise that the environmental impact of information technology lies primarily in the production of equipment and computing infrastructure, rather than in its operation. Despite energy-efficient innovations, overall CO

2 emissions continue to increase due to the global growth of the IT sector. They recommend including the life cycle of technology in sustainability assessments.

The research in [

24] organises 473 Scopus articles on the impact of digital technologies on the achievement of the SDGs. Digital technologies play a key role in achieving the SDGs by providing innovative solutions to global challenges such as poverty, health, climate change, and responsible consumption. Artificial intelligence (AI) supports automation and predictive analytics to improve health services (SDG 3) and combat climate change (SDG 13), while blockchain enables transparency and ethical governance (SDG 16). The internet of things (IoT) facilitates real-time monitoring for smart cities (SDG 11) and energy efficiency (SDG 7), and big data strengthens supply chains and agricultural productivity (SDG 2). Cloud computing and 5G networks improve collaboration and infrastructure (SDGs 9, 17), while remote sensing and GIS provide data for environmental monitoring (SDGs 14, 15). Digital technologies thus optimise resources, improve decision-making, and accelerate progress towards the SDGs. The authors conclude that digitalisation can accelerate progress on the SDGs, especially SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), through increased efficiency and transparency. However, the study points to significant gaps, such as the “digital divide,” which could widen the gap between countries that have access to technology and those that do not. A limitation of the work is that it is survey-based and does not provide empirical data to quantify the impact.

The next paper [

25] analyses the impact of robotics and autonomous systems on the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through a horizon scan involving 102 experts from around the world. The main findings show that these technologies have the potential to transform approaches to achieving the SDGs by replacing or supporting human activities, facilitating innovation, improving remote access and monitoring, particularly in health, agriculture, and biodiversity management. However, threats are identified, such as increasing inequality, worsening environmental change, diverting resources from proven solutions, and reducing freedoms through insufficient regulation. Limitations of the study include the difficulty of predicting long-term impacts due to the rapid evolution of technologies and the lack of analysis of specific regional contexts.

The authors of [

26] highlight the transformative role of technology in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4, which aims to ensure inclusive and quality education in Nigeria. The results of a systematic review of 51 sources show that digital tools such as online platforms, virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), and artificial intelligence (AI) and data analytics significantly expand access to education, reduce inequalities between well-off and underachieving schools, and facilitate personalised learning that increases student engagement and improves learning outcomes. Technology also contributes to effective education governance by optimising resource allocation and decision-making, and promoting environmental education that supports sustainability. However, the digital divide, limited access to technology and the internet, and insufficient digital literacy remain significant barriers. A limitation of the study is the focus of the analysis on Nigeria, which may limit the generalizability of the findings.

Overall, progress towards the SDGs is being significantly hampered by unclear metrics, global crises (pandemics, wars, economic instability), and geopolitical confrontation. Economic growth and investment (in particular public) are positively correlated with SDG implementation, but without green, circular, and structural reforms, this is not enough. Geopolitical instability further highlights the need for institutional reforms and diversification of financing. Thus, holistic policies, institutional modernisation, investment in the circular economy, and global cooperation are vital to achieving the SDGs by 2030. Geopolitical stability and multilateral cooperation are crucial to overcoming obstacles to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, especially in conflict-affected regions. This means that to achieve the SDGs, countries must focus on economic growth while respecting the constraints imposed by other SDGs.

Thus, most studies focus on individual aspects of the SDGs (for example, economic growth or climate change), but lack a comprehensive analysis of the interrelationships between economic, geopolitical, and technological factors. In addition, many studies use data up to 2020, which does not take into account post-pandemic changes.

As a result of the analysis, the following hypothesis is formulated for testing: in modern geopolitical realities, under the current economic model, countries of the world have decreased opportunities to achieve the SDGs due to the inability to ensure economic growth and its components.

In addition to this general hypothesis, we formulate several specific research hypotheses to guide the empirical analysis:

H1: The stagnation of global trade since 2011 significantly limits the achievement of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

H2: The regionalisation of trade reduces opportunities for low- and middle-income countries to progress on SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

H3: Increasing automation reduces employment and weakens the middle class, thereby slowing progress on SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

These hypotheses ensure a stronger connection between the literature review and the empirical findings of our study.

3. Methodology

This article uses a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods to analyse the impact of economic growth and geopolitical changes on the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Quantitative methods include statistical data analysis, comparative analysis, and predictive modelling based on trend models to assess the dynamics of GDP, FDI, and exports. This allows us to assess global and regional trends, as well as identify the reasons for slowing down the progress of the SDGs. The limitations of the methodology include the lack of complex econometric models, such as panel regressions, due to the limited availability of data for all countries for the entire period 2005–2024. The qualitative analysis includes a systematic review of the literature, a synthesis of reports from the UN, the World Bank, and the IMF, as well as an expert assessment of the impact of geopolitical factors on the SDGs.

To avoid ambiguity, we clarify that predictive modelling in this study refers primarily to long-term trend analysis (linear regressions of GDP, FDI, exports, and debt). It does not involve advanced forecasting techniques. The assumptions include the use of constant 2004 USD prices, World Bank income-based country grouping, and a fixed time frame of 2005–2024. Data validation was ensured by cross-checking figures across World Bank, IMF, and OECD datasets. A summary of methods can be presented as follows:

Quantitative analysis: trend models and compound growth calculations;

Qualitative analysis: expert assessment and synthesis of international reports;

Predictive modelling: linear regression-based extrapolation of long-term trends.

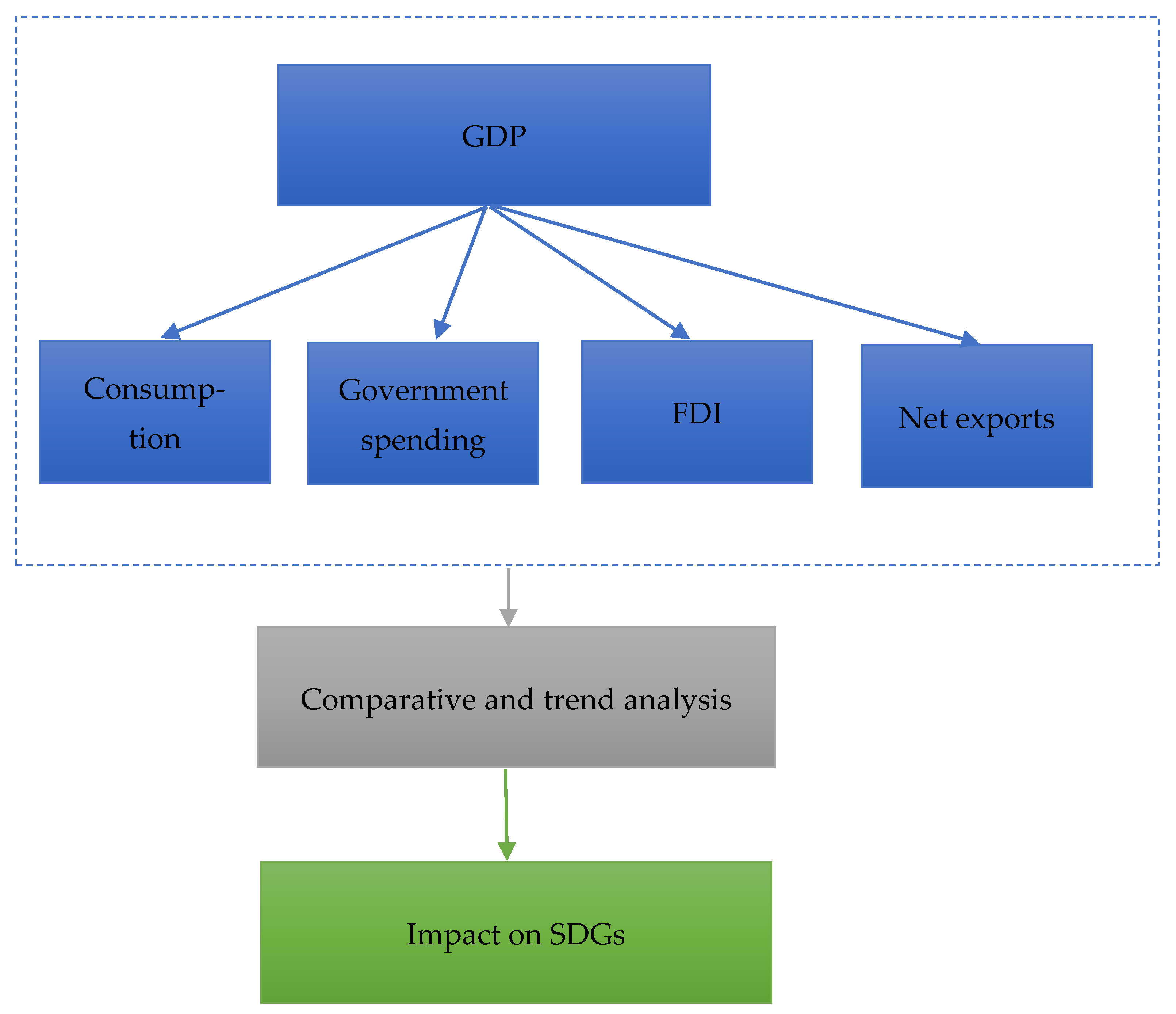

The research model is based on the analysis of four components of GDP (consumption, government spending, FDI, and exports) as indicators of economic growth and their impact on the SDGs. The study uses comparative models, rather than causal ones, since the main goal is to identify global trends and patterns in the progress of the SDGs, rather than establishing direct cause-and-effect relationships. To analyse the dynamics of variables, trend models, in particular linear regression, are used in some cases, which allows assessing long-term trends in GDP, FDI, exports, and public debt for the period 2005–2024 and their relationship with the achievement of the SDGs (

Figure 1).

The study is based on data from reliable international sources that ensure the reliability and comparability of information: World Bank (World Bank Open Data), International Monetary Fund (IMF), International Federation of Robotics (IFR), UN SDG Reports (2020–2024), OECD. Data covers the period 2005–2024 to provide long-term trend analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted for three groups of countries (high, middle, and low income) to assess key economic indicators such as GDP, final consumption, FDI, exports, and public debt. To calculate the average annual growth of indicators (final consumption, exports, FDI, GDP), the compound percentage growth formula was used:

where

Vt—the final value of the indicator,

V0—is the initial value,

n—is the number of years in the sample.

To calculate real exports, an adjustment for US dollar inflation according to IMF data was taken into account, which allowed considering growth in constant prices. The presented methodology provides a comprehensive approach to the analysis of economic growth and geopolitical changes in the context of the SDGs, combining quantitative data with qualitative findings for a comprehensive understanding of the problem.

4. Results

4.1. Consumption Stimulation

As is known, economic growth is usually measured using the GDP indicator which, although it has many shortcomings [

27], is an indicator for comparing the standard of living of the population. It consists of four main components: the level of final consumption, government spending, investment, and net exports. A. Stavytskyy et al. [

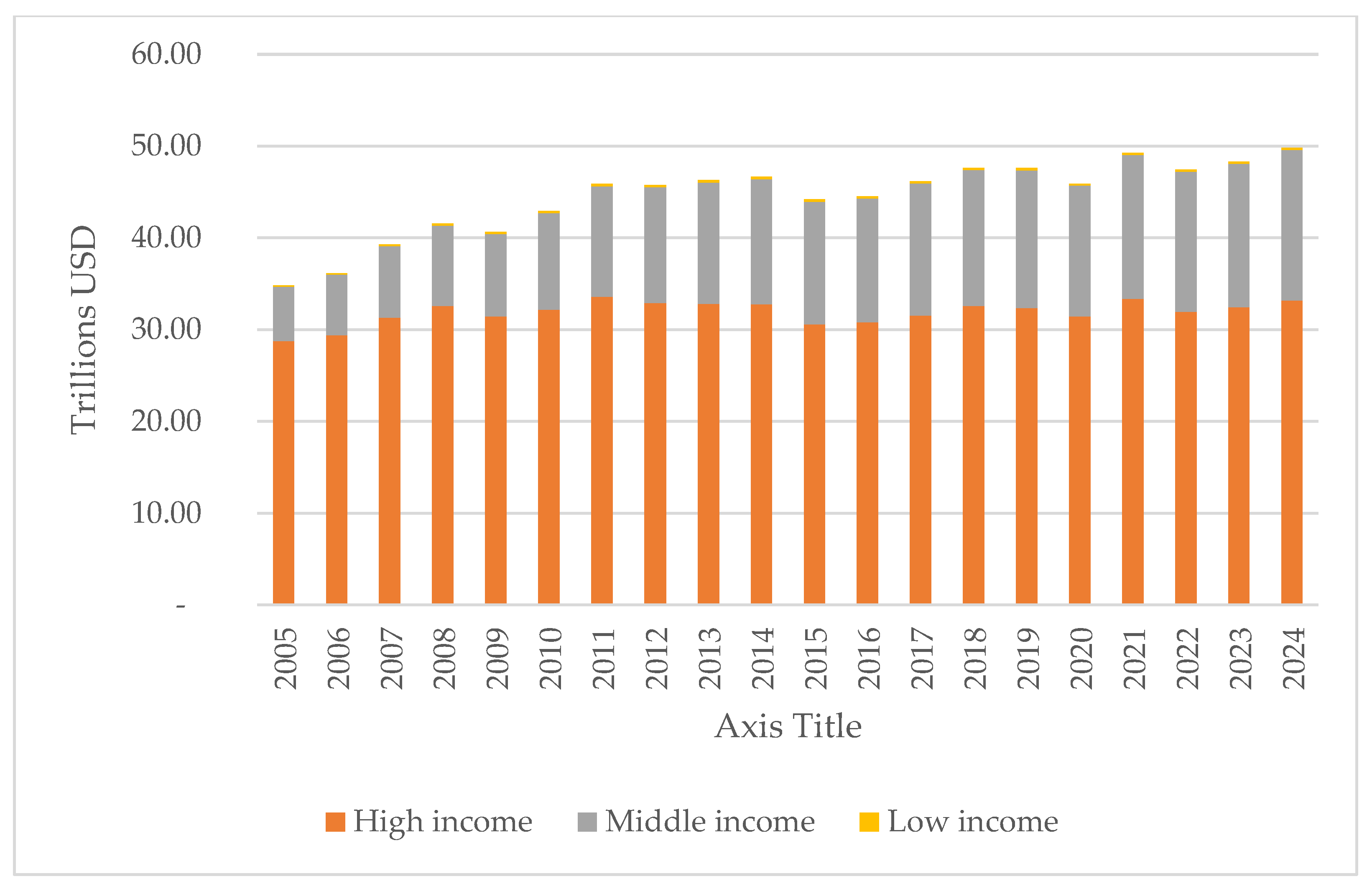

28] conducted a study on how the level of final consumption per capita varies in countries and regions of the world. The results showed that the change in the level of consumption per capita is extremely uneven: richer countries, even with slow growth, significantly increase the gap with poor countries. In particular, consumption in real terms (when freed from inflation) grew during 2005–2024 in high-income countries by an average of 0.8%, in middle-income countries by 5.5%, and in low-income countries by 2.6% (

Figure 2).

However, the economic model for stimulating individual consumption is effectively exhausted in developed countries; that is, consumption growth cannot compensate for the decline in female fertility and the ageing of the population. The slow growth of consumption in high-income countries is the result of a combination of market saturation, demographic ageing, high debt burden, low real income growth, changes in consumer preferences, economic uncertainty, monetary policy, and environmental factors. These factors together limit the dynamics of consumer spending; accordingly, many countries need other incentives to achieve economic growth.

4.2. Stimulation Through Public Spending

Various factors have been used as such incentives in recent periods. The simplest is the growth of government spending, which stimulates economic activity. Many countries have actively used this, increasing public debt. Today, the possibilities for such stimulation, if not exhausted in most countries, are significantly limited due to the amounts of accumulated debts. In particular, in 2023, global debt amounted to USD 307 trillion [

29], of which approximately USD 92 trillion was government debt [

30]. Of this amount, almost three-quarters of the debt was issued by high-income countries, slightly less than a quarter by middle-income countries, and about 4% by low-income countries. At the same time, the average ratio of public debt to GDP increased from 60% in 2005 to 93% in 2024, but this ratio for high-income countries increased from 70 to 100%, while for middle-income countries it rose from 45 to 69%, and for low-income countries fluctuated at 36–50% without a specific trend [

31]. Thus, only middle-income countries can still increase their borrowing; however, even if they reach 100% of the debt-to-GDP level, this will increase the global ratio by only 4–5%. However, it can be seen that further growth of debt on a global scale already seems very threatening for the economic system, so directly increasing debt can no longer be a driver of economic growth.

4.3. Stimulation Through Investment Attraction

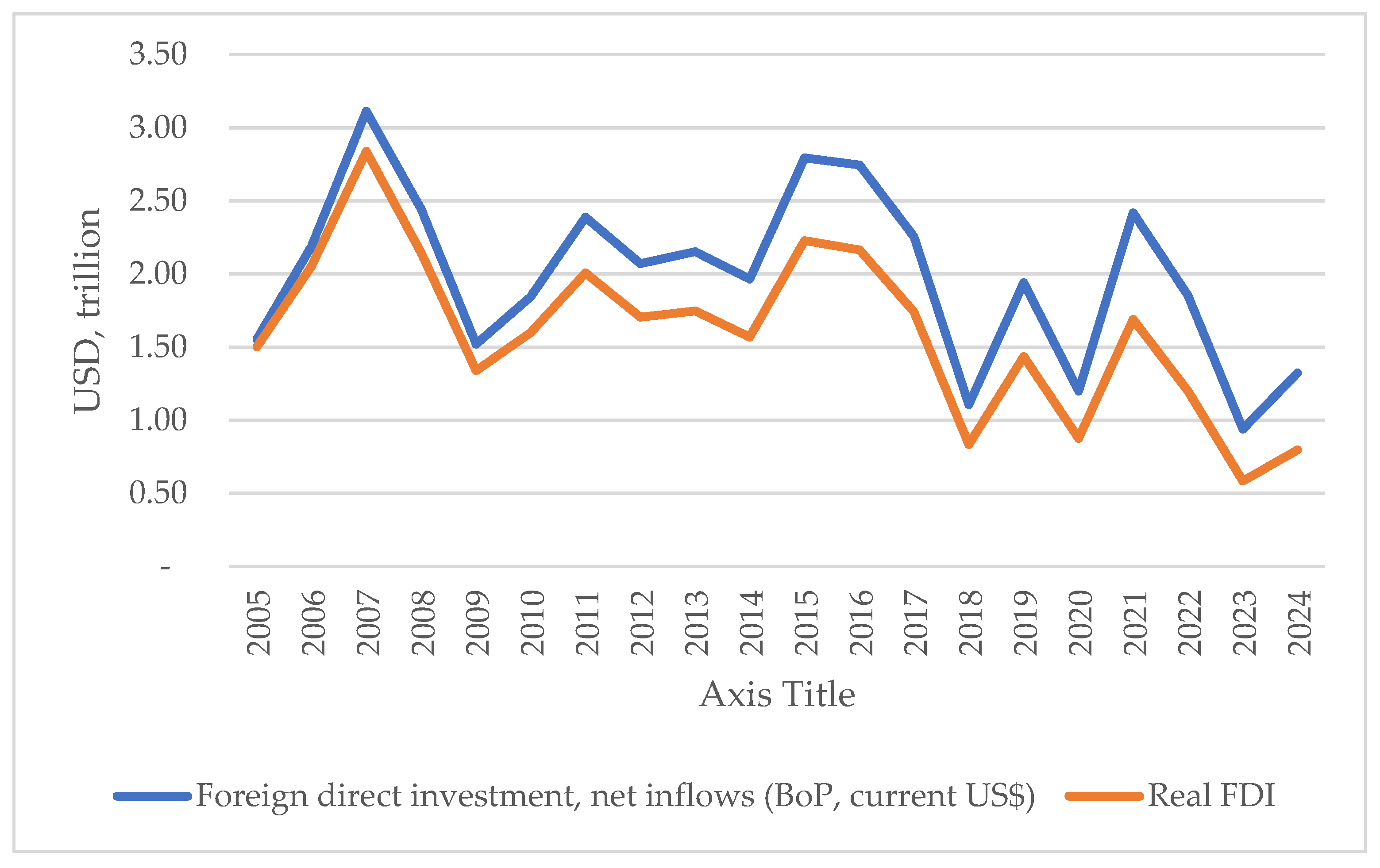

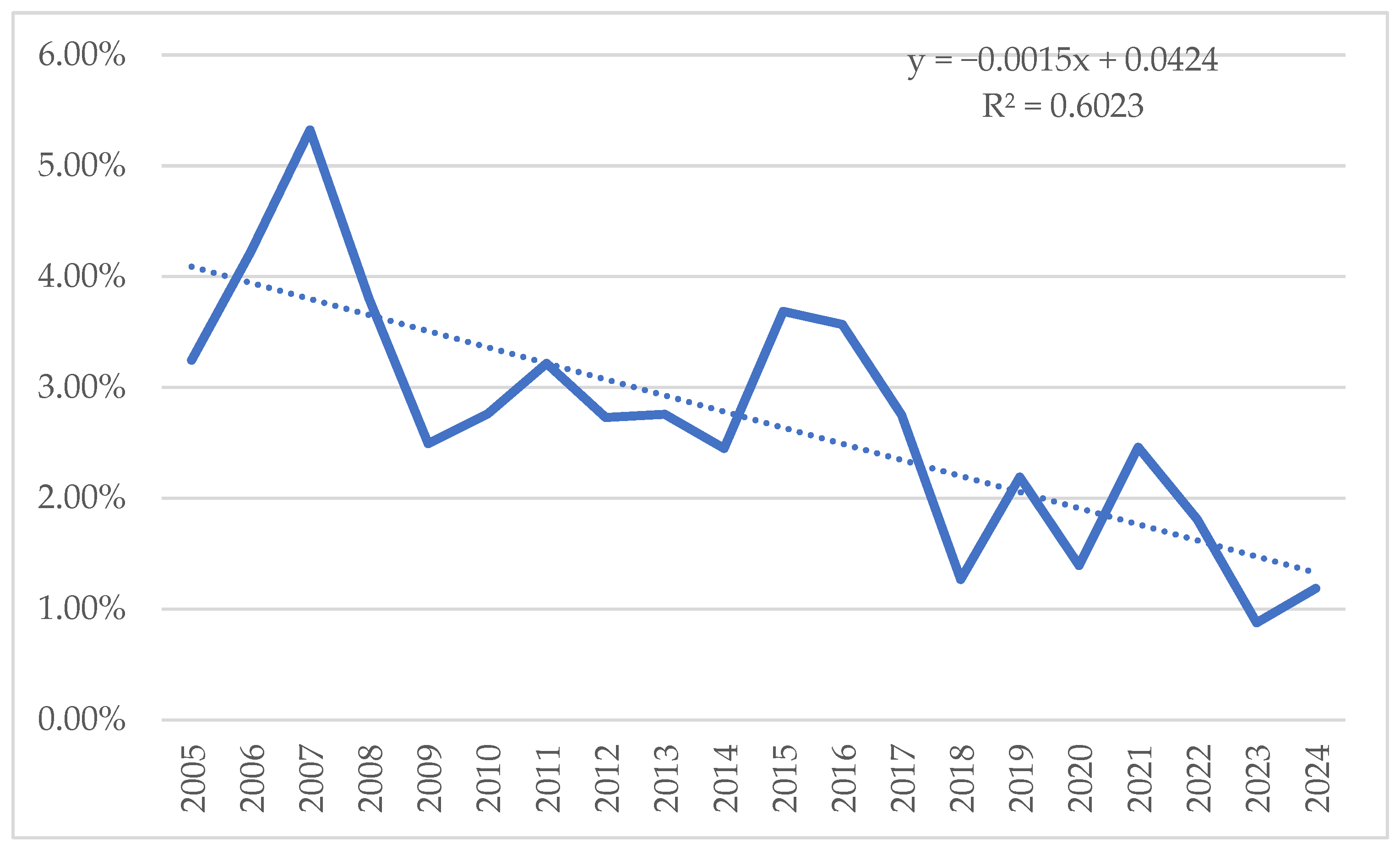

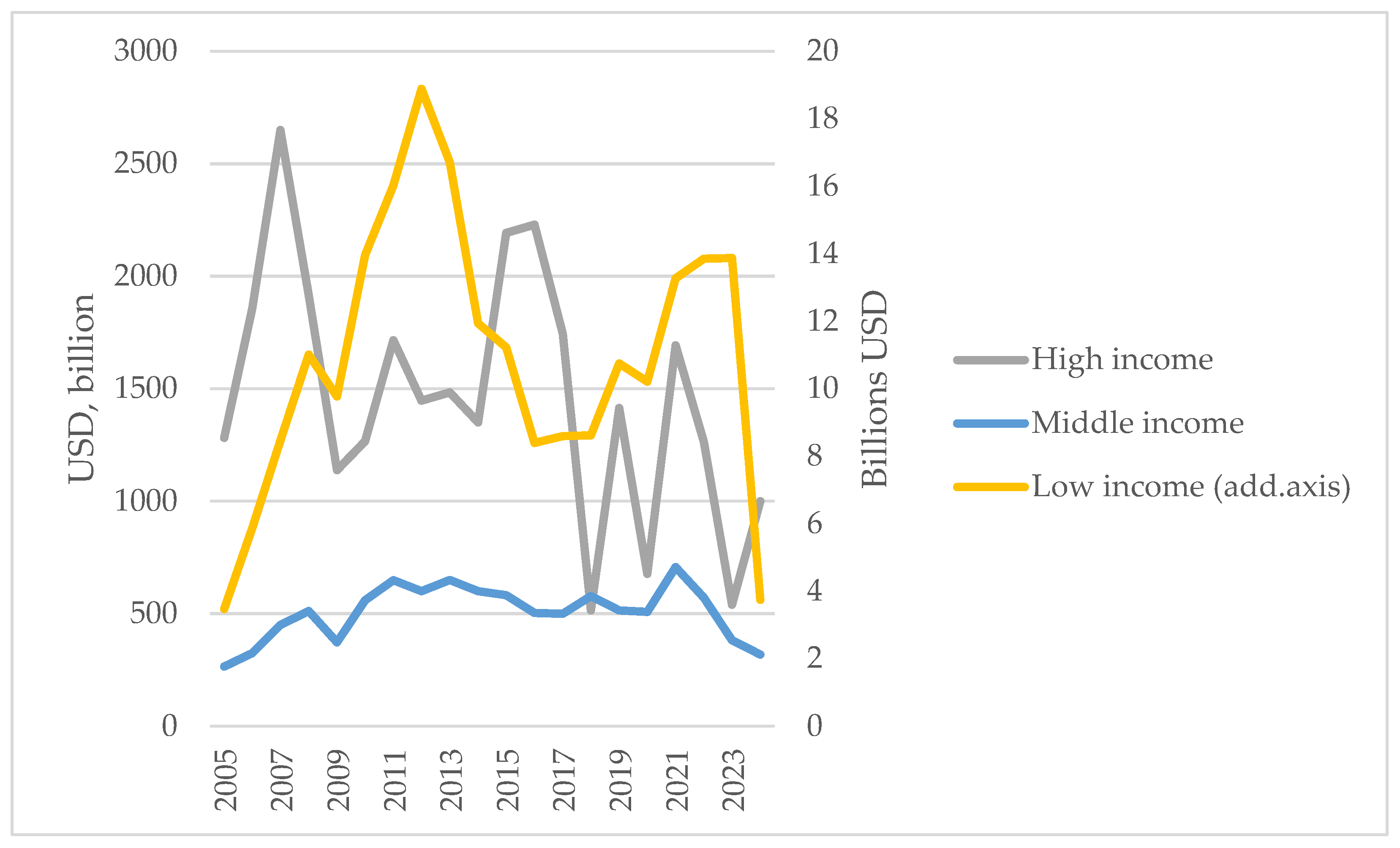

Another opportunity for growth is attracting investment. However, here too, we can see that the global trend is negative, both in nominal and real terms. Since 2005, investment has almost halved in real terms, and in nominal terms by about 15% (

Figure 3). This means that the opportunities for attracting investment for specific countries are significantly complicated. Moreover, the share of FDI in global GDP is constantly decreasing, having already fallen three times in 20 years (

Figure 4). Of the entire set of countries, only 27 can boast that over 20 years, the real inflow of FDI was higher than the growth of GDP.

At the same time, there is a significant unevenness of FDI between countries (

Figure 5). High-income countries have 2–5 times more FDI than middle-income countries and almost 1000 times more than low-income countries. Of course, it can be stated that low-income countries usually have institutional problems with courts, corruption, etc., which make significant FDI impossible, but such a distribution clearly does not allow achieving either economic growth or the SDGs.

4.4. Export Promotion

The third factor is the increase in net exports, which in practice looked like an increase in exports due to the use of certain restrictions on fixing the exchange rate or forced devaluation [

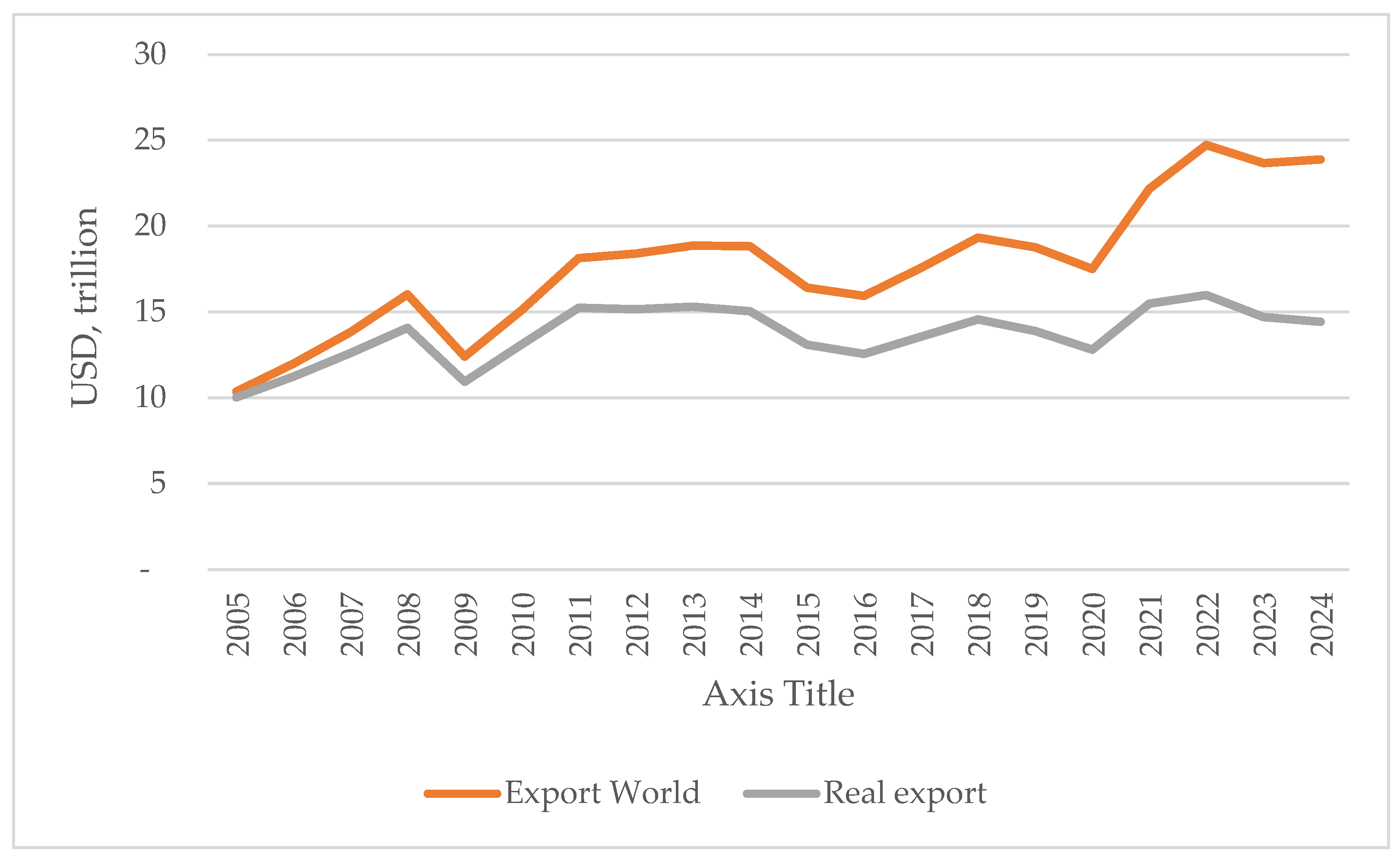

33]. A significant number of countries have relied on the export model of the economy, increasing the volume of exports. Over the past 20 years, world exports have grown in nominal terms from USD 10.3 trillion to USD 23.9 trillion. However, this period was accompanied by quite rapid dollar inflation, so a fairer comparison would be real exports; that is, in constant dollars, for example, in 2004.

Figure 6 shows the dynamics of world exports from 2005 to 2024 in nominal and real terms. It can be seen that since 2011, world exports have remained essentially at the same level without significant changes, fluctuating in the range of USD 12.5–16.0 trillion in 2004 prices. Thus, we can conclude that global trade in goods has not increased in the past 10 years. If we take the growth of exports in nominal terms, during 2005–2014, the average annual growth was 6.9%, but during 2015–2024, only 4.3%. At the same time, in constant prices, the corresponding indicators are 4.6% and 1.1%. In total, over 20 years, growth in nominal terms was 4.5%, and in real terms, 1.9%. At the same time, global GDP over this period grew by 2.84% in constant prices, and the difference between the two decades is insignificant: 2.9% during 2005–2014 and 2.75% during 2015–2025. This means that despite the growth of the planet’s population, technological development and other incentives, exports of goods do not show growth proportional to GDP.

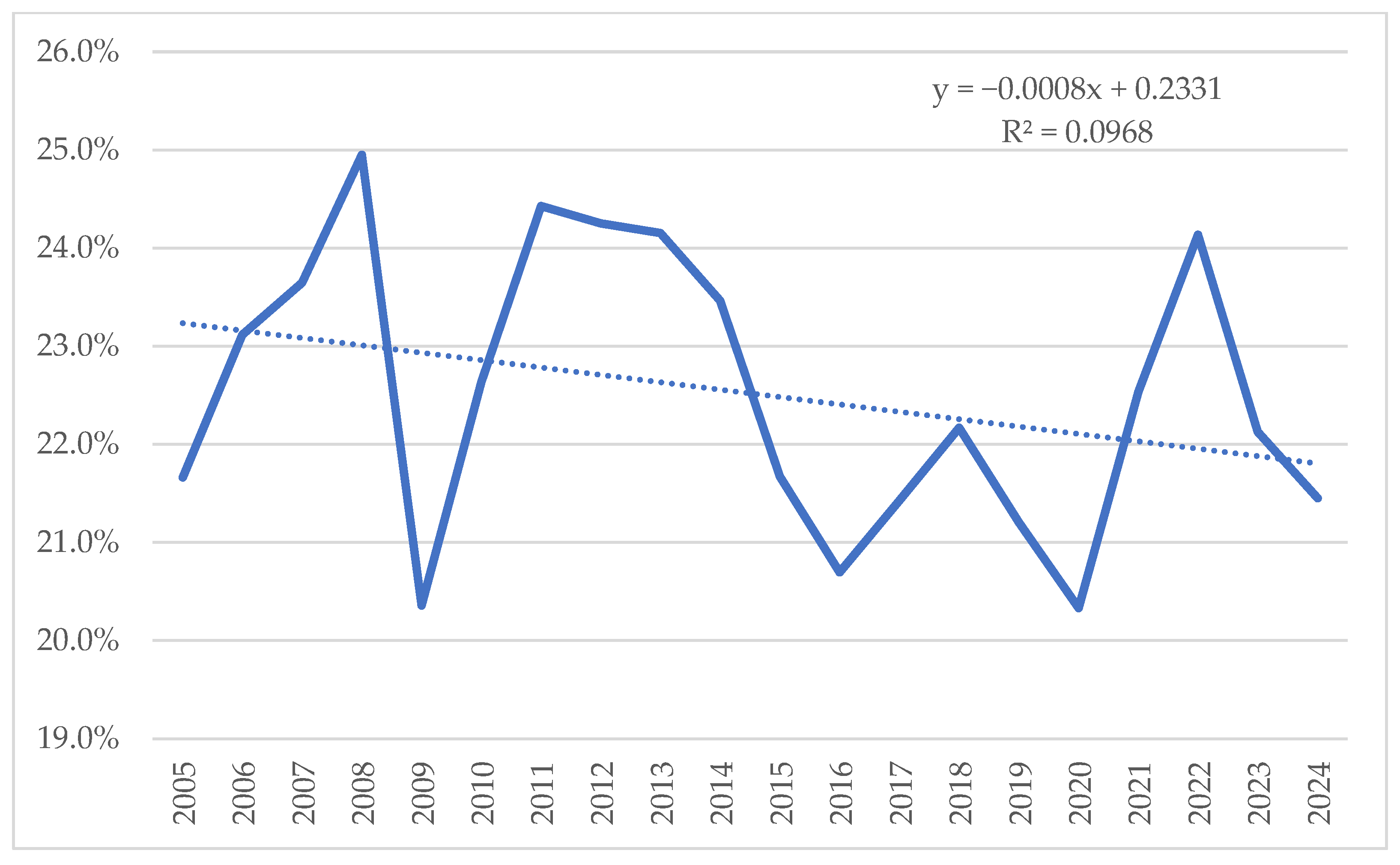

This conclusion is also confirmed by the dynamics of the share of total exports of goods in world GDP (

Figure 7). Over 20 years, there have been fluctuations of between 20 and 25% of GDP with a slight negative trend.

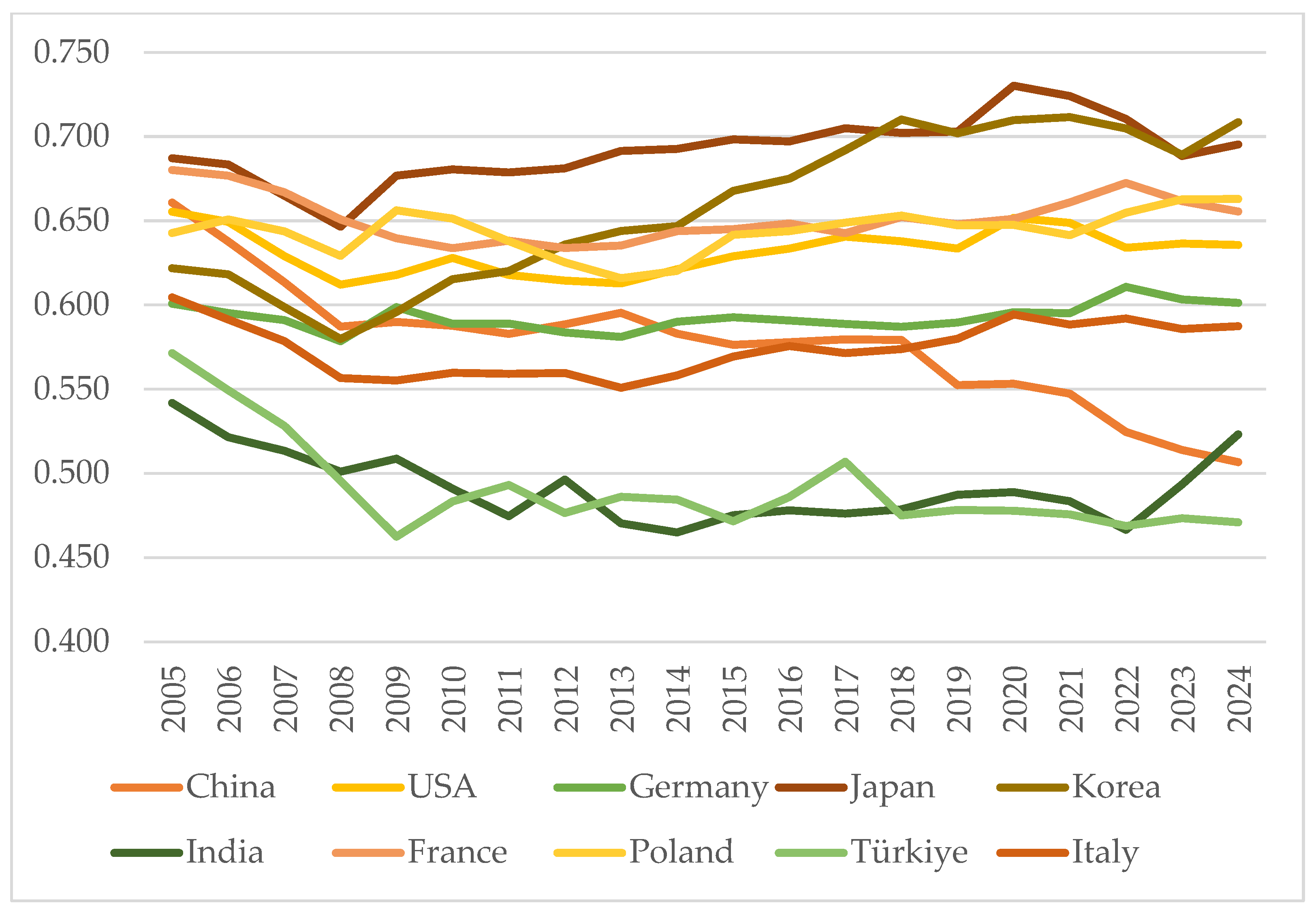

When calculating the growth rate of exports of goods over the past 20 years, net of US dollar inflation (2.51% per year), for countries that exported at least 0.2% of total exports, it turns out that significant average annual growth in real exports was recorded in Vietnam (13.0%), Bangladesh (7.5%), and China (6.0%). Another 17 countries had real growth that exceeded the average annual GDP growth (2.84%). The remaining 33 countries had real growth less than GDP growth, and 7 of them had negative growth. Thus, the export component for most countries is not the basis for economic growth at this stage.

It is also worth noting that in almost all countries of the world, the share of exports going to major trading partners does not actually change, which indicates the lack of further diversification of exports. For example, in the USA, the top five importing countries buy 48.2% of all exports, and the top ten buy 63.6%. In Germany, these figures are 36.7% and 60.1%, respectively. Only a few countries have been able to increase export diversification over the past two decades. First of all, we are talking about China which, due to access to new markets, was able to reduce the weight of the top five partners from 54.1% in 2005 to 35.7% in 2024, and the top ten decreased from 66.1% to 50.7%. Turkey also has quite diversified exports, for which these figures are 29.8% and 47.1%, respectively (

Figure 8). However, other countries have encountered the process of regionalisation. For example, Korean exports to the top five countries increased from 46.8% to 56.9%, and to the top ten from 62.2% to 70.9% over two decades. Overall, the graph shows that among the largest exporters, only China continues to diversify its exports. Thus, we can see that the world does not have a tendency towards further globalisation in trade, but most likely, we expect further regionalisation of countries and the creation of our own cluster countries.

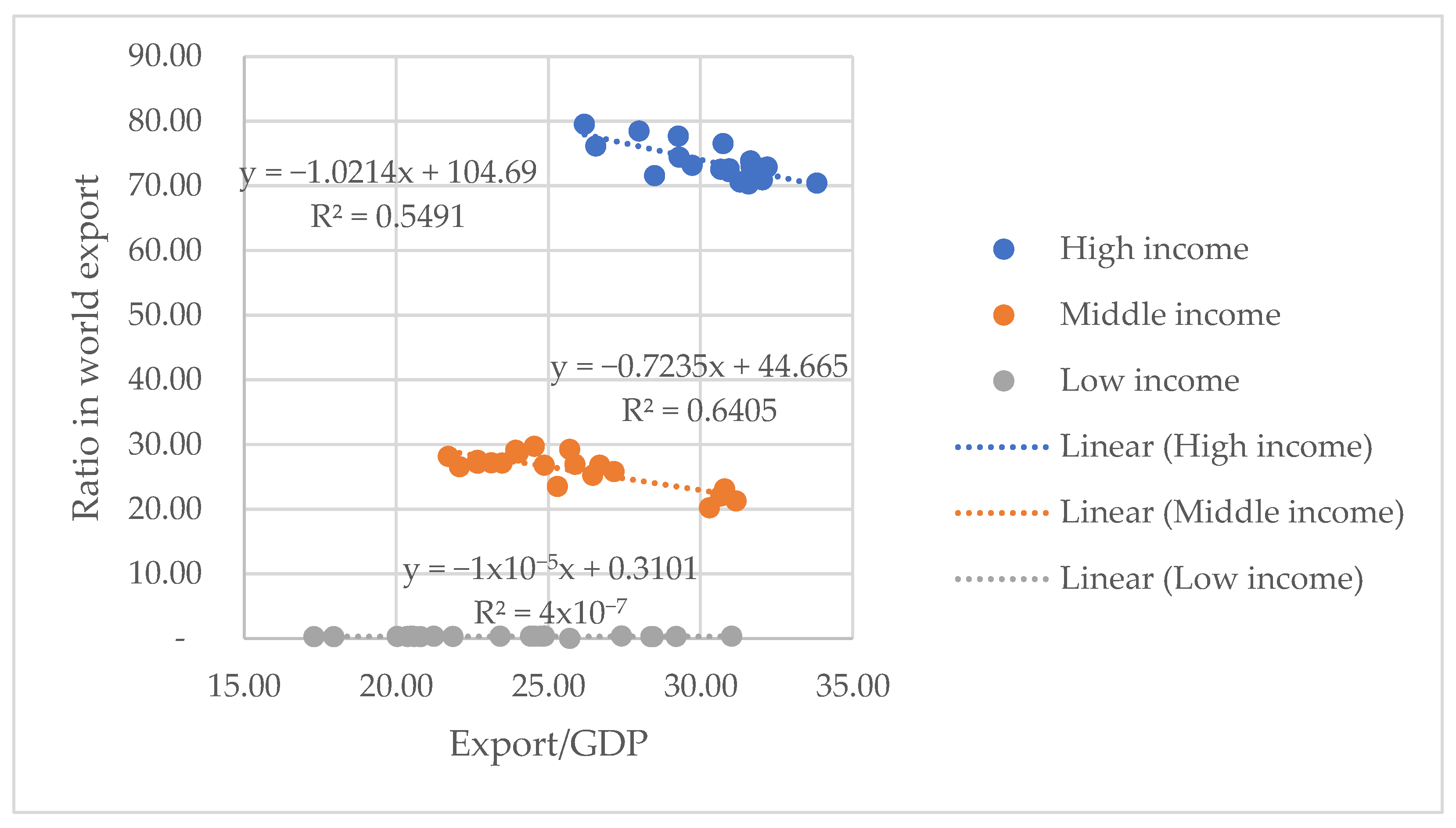

This view is supported by another diagram (

Figure 9), which shows that a higher ratio of exports of goods and services to GDP is typically associated with a lower share in world trade. Thus, poor countries, whose trade does not exceed 1% of world trade, do not have the opportunity to grow in the modern world through the export model.

5. Discussion

Countries can use several factors to increase their level of economic activity. First, this is the level of final consumption, which can be stimulated by new technologies, affordable loans and the creation of a consumption paradigm in the country. However, in most rich countries of the world, there is a systemic slowdown in this indicator, which indicates the limitations of the current economic model. At the same time, in middle-income countries, there are opportunities for GDP growth due to technological development and achieving a new level of consumption, but only to the level of more developed countries.

Secondly, the level of foreign investment; however, in the world over the past decades, there has been a significant reduction. For high-income countries, this is a natural phenomenon due to the saturation of the economy. However, for middle- and low-income countries, such a slowdown poses a threat, as it limits opportunities for further economic growth. The volume of foreign investment in the poorest countries is so small that it does not contribute significantly to their development.

Third, there is the possibility of state stimulation of the economy. In most countries of the world, these reserves are practically exhausted. Only some middle-income countries still have some opportunities to stimulate economic development, bringing it closer to the level of high-income countries. Examples of stimulating the economy during a pandemic or military conflicts have shown that GDP growth is much less than the stimulation itself.

Finally, another factor is the construction of an export-oriented economic model. However, the study shows that the possibilities for this are also limited. The lion’s share of world exports is formed by rich countries that have the resources and technologies to create goods with high added value. Other countries have much lower export potential. Moreover, the decrease in the level of globalisation forces them to specialise in production for a limited number of partner countries. This creates the prerequisites for the fragmentation of economies, localisation of production, and the formation of regional economic systems.

Thus, none of the components of GDP is currently a sufficient incentive for further economic development. The modern economic model is experiencing a crisis and requires significant improvement. Problems in its functioning create the prerequisites for restructuring the world economy, which may be accompanied by a redistribution of resources. This is already evident in the number of military conflicts that tend to escalate. The main contradictions arise between high- and middle-income countries, and the nature and geographical structure of these conflicts will largely depend on how countries implement the localisation of production. The localisation of production in countries seems to be a rather natural phenomenon, given that efficient production requires economies of scale, and some countries introduce tariffs or quota restrictions on imports [

35].

In the current economic situation, most countries in the world will be interested in introducing various tariffs on imported products and restricting the export of raw materials. An example is China which, using control over the supply of rare earth metals, was able to reach more favourable tariff agreements with the United States of America. This demonstrates that only countries with powerful production of critical goods can count on economic protection. As a result, a significant number of countries will focus on expanding local production and its automation in accordance with modern technologies. This will contribute to the growth of production volumes and, accordingly, opportunities for reorienting economies in the short term for economic growth. However, all measures aimed at protecting national economies can only exacerbate the upcoming economic crisis.

Rebooting the country’s economic system requires a major restructuring, including the use of new technologies. The country’s choice of economic bloc (conditionally pro-Chinese or pro-Western) will determine its technological and economic development in the long term. Such a choice affects not only economic orientation but also the use of human capital. In Asian markets, human capital is often used as a cheap alternative to automation, while in Western countries, the use of automated equipment is constantly growing, and technologies are aimed at replacing human labour.

The introduction of industrial robots in the United States and Western Europe has led to a decrease in employment in low-skilled occupations, in particular in the mechanical engineering and automotive industries. In the United States, between 1990 and 2007, one additional robot per 1000 workers reduced employment by 0.18–0.34% and lowered wages by 0.25–0.5%. In Western Europe (in particular, Germany, France), the number of industrial robots increased from 1.2 per 1000 workers in 1993 to 3.4 in 2014. However, automation not only replaces human labour but also creates new jobs in sectors related to the development and maintenance of technologies [

36].

According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), the annual volume of industrial robot installations in the world exceeds half a million units annually, which indicates a steady trend towards automation of production. In 2023, 541,302 robotic systems were put into operation, with the bulk of installations in Asia (70%), while in Europe and America, this figure was 17% and 10%, respectively [

37]. However, countries focused on the Western market already have a high level of automation, although the growth rate is slower due to the developed technological base. In particular, in 2021, South Korea was the world leader with a robot density of 1000 robots per 10,000 workers, which is more than three times higher than the global average (126 units in 2020) [

38].

On average across OECD countries, the share of jobs at high risk of automation is 27%, and a further 36% of jobs will experience significant task changes due to automation, although they will not necessarily be completely replaced by machines [

39]. The increasing use of industrial robots is reducing the need for routine manual work, while at the same time increasing the demand for specialists with technical, engineering, and digital competences. This applies in particular to skills in programming, robotics, data analytics, and the adaptation of production processes to new technologies.

It can be noted that in Asia, automation is more threatening to low-skilled jobs, while in Western countries, new jobs are being created in technology sectors, which partially compensates for the losses. Accordingly, the requirements for workers differ significantly: in Asian countries, the emphasis is on certain technical skills and competencies, while in the West, critical thinking, adaptability, and the ability to work in non-standard situations are valued.

These differences are changing our understanding of the middle class as the basis of sustainable growth. Previously, it was considered a group of skilled blue-collar and office workers, but the development of automation and artificial intelligence has significantly reduced these jobs. On the one hand, this reduces the level of consumption, which slows down economic growth, and on the other hand, it promotes investment in enterprises that introduce a high level of automation and artificial intelligence which, in turn, increases economic performance. However, fewer and fewer workers are needed to support automated lines, and the role of human capital is changing. Most representatives of the middle class will either move to unskilled labour or become highly skilled personnel with unique competencies. The decline of the middle class not only reduces the level of consumption but also simplifies the structure of demand, which can be satisfied with less complex production and fewer resources. This poses serious risks for the political systems of countries around the world. The shrinking middle class may encourage politicians to target the poor or the premium consumer segment. On the one hand, this will generate controversial policies; on the other hand, it will undermine democratic principles. Competition between conventional “technocratic” and “populist” approaches may lead to a decline in the level of democracy. Previous decades have shown the advantage of democracies in competition with authoritarian regimes [

40]. However, now authoritarian regimes show better economic results, especially in middle-income countries, where authoritarian governments are concentrated. Their growth has created the illusion that authoritarianism contributes to economic development, although in fact it is the result of “catch-up” income growth in these countries.

Such significant changes will create the prerequisites for the formation of a new economic model, which will be based in part on new ideas, in particular the concept of an unconditional basic income or the application of progressive taxation with greater differentiation by income. However, the decline in the general standard of living may make these ideas less realistic. Instead, governments should focus on modernising the taxation system in accordance with new economic realities. Taxation of human labour, which in modern conditions is becoming less and less controlled, needs to be reconsidered. Automated production and the provision of services are increasingly carried out remotely, without additional registration, which requires fundamentally new approaches to regulating and streamlining these processes.

6. Conclusions

The study identified key reasons for the slowdown in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the world. Analysis of statistical data, comparative analysis, and a review of scientific literature confirm that the modern economic system is unstable and unable to ensure sustainable development in most countries of the world. Economic growth, measured by GDP, remains a key factor for achieving the SDGs, but its potential is being exhausted. The average annual growth rate of final consumption in high-income countries was less than 1% for 2005–2024. However, market saturation, demographic ageing, a high debt burden, and declining foreign direct investment (FDI) limit growth opportunities. Exports, as a component of GDP, do not show significant growth in real terms, which indicates the stagnation of global trade after 2011.

World trade is increasingly characterised by regionalisation rather than globalisation. The share of exports to the top 10 trading partners remains stable or increases in almost all countries in the world except China. This indicates the formation of regional economic clusters, which complicates global cooperation within the framework of SDG 17 (Partnership for the Goals). Trade restrictions such as tariffs and quotas increase the fragmentation of economies and hinder the achievement of the SDGs in the future.

Thus, the hypothesis put forward in the study is generally confirmed. The countries of the world will indeed not be able to achieve the SDGs in modern geopolitical realities due to the impossibility of ensuring economic growth and its components. This means that they are forced to set their own local goals, reducing the level of globalisation.

Localisation of production, aimed at economies of scale and protecting national economies, is a response to the decline in globalisation, but it creates new risks. It requires significant investments in technology, human capital, and resources, which is problematic for middle- and low-income countries due to low FDI inflows (1000 times lower than in rich countries). The energy challenge, in particular the dependence on imported energy and the slow growth of the share of renewable energy, complicates the achievement of SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy).

In Western countries, automation of production reduces employment in low-skilled occupations but creates jobs in technology sectors. In Asia, automation threatens low-skilled jobs, while human capital is used as a cheaper alternative. This creates an inequality in skill requirements: the West values critical thinking, while Asia values technical competencies.

In such conditions, the decline of the middle class due to automation and economic crises reduces consumer demand and simplifies the structure of the economy, which threatens political stability. With increasing automation, the widespread introduction of AI will contribute to the polarisation of society, where populist and technocratic approaches can undermine democratic principles. Authoritarian regimes in middle-income countries demonstrate faster economic growth, creating the illusion of their efficiency, but this is the result of “catch-up” development, not a sustainable economic model.

Geopolitical instability is disrupting supply chains, technology transfers, and international cooperation, hampering SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 17. The rise in the number of displaced people to 120 million and civilian victims of conflict is complicating SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). Insufficient funding for the SDGs and weak cooperation due to protectionism are hampering progress.

The current economic model has reached its limits due to limited growth incentives (consumption, FDI, government spending, exports). Proposed solutions such as a universal basic income or progressive taxation may be less realistic due to the decline in living standards. Instead, countries need tax reforms (primarily labour taxation) geared towards automated production and modernising institutions to support a circular economy.

The formulated hypotheses (H1–H3) are generally supported by the empirical analysis. In particular, stagnation of global trade since 2011 corresponds with the limited progress on SDG 17, confirming H1. Evidence of increasing concentration of exports within regional blocs supports H2, as regionalisation constrains the opportunities of low- and middle-income countries to expand integration and achieve inclusive growth (SDG 8) and reduce inequalities (SDG 10). Finally, the observed decline of the middle class and rising risks of job losses due to automation provide evidence consistent with H3, demonstrating how technological change undermines progress on poverty reduction and inequality. These results reinforce our conclusion that structural global trends—trade stagnation, regionalisation, and automation—are central barriers to achieving the SDGs under the current economic model.

Nevertheless, several limitations of the study should be emphasised. First, the grouping of countries by income level, while useful for comparability, may obscure important within-group differences related to governance, policy context, or regional characteristics. Second, the correlational nature of the analysis prevents establishing causal relationships. More advanced econometric techniques, such as panel regressions, could strengthen causal inference in future research. Third, qualitative assessments—although informed by expert reports—are subject to interpretation. These limitations highlight the need for complementary studies that integrate econometric modelling, institutional factors, and micro-level data.

The study confirms that the current economic system does not provide sustainable development due to the exhaustion of traditional growth drivers, regionalisation of trade, geopolitical instability and social challenges associated with automation and the loss of the middle class. To achieve the SDGs, radical reforms are needed aimed at inclusive growth, decarbonisation of the economy, and strengthening global partnerships around the world. However, as the practice of recent years shows, the world is not ready for such reforms, so the contradictions between countries will only intensify.

The analysis shows significant differences in progress towards the SDGs across income groups. In high-income countries, final consumption growth is only 0.8% per year (2005–2024), reflecting market saturation and demographic ageing, while in middle-income countries, consumption growth has reached 5.5%, but is limited by low levels of FDI and debt burdens. In low-income countries, consumption growth is 2.6%, but their access to FDI is minimal (1000 times lower than in high-income countries), making it difficult to achieve the SDGs. Regionalisation of trade and geopolitical barriers affect low- and middle-income countries the most, limiting their integration into global markets and access to resources for sustainable development.

Limitations of this study include the correlational nature of the analysis, which does not allow for causality, and the use of country groupings by income, which may mask within-group differences. This should be the subject of further research.