S + ESG as a New Dimension of Resilience: Security at the Core of Sustainable Business Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Reducing economic dependence on authoritarian states by diversifying sources of critical resources and relocating production to secure jurisdictions;

- Modernizing the economic policies of democratic countries by involving the private sector in the financing of security initiatives;

- Physical security—protection of life, health, and critical infrastructure;

- Cybersecurity—safeguarding digital systems, assets, and personal data;

- Information security—countering disinformation, propaganda, and fake news;

- Environmental security—preventing ecological disasters and controlling environmental impact;

- Social security—ensuring justice, mitigating inequality, and supporting vulnerable groups;

- Economic security—market stability and protection of investments;

- Institutional/governance security—transparency, administrative stability, and trust in public institutions;

- Cultural/humanitarian security—protection of identity, language, and traditions in the face of global threats.

- To what extent does Security represent a distinct dimension beyond the existing ESG framework in the Ukrainian context?

- How do Ukrainian professionals across business, government, and civil society perceive the role of Security in ensuring sustainable development and resilience?

- Can elevating Security to a stand-alone pillar within ESG (SESG model) strengthen organizational and societal resilience in fragile environments?

- H1: Security considerations are perceived by stakeholders as equally or more important than traditional ESG dimensions in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

- H2: The integration of Security into the ESG framework (SESG) significantly enhances the explanatory power of ESG in capturing resilience-related challenges.

- H3: The prioritization of Security within sustainability frameworks varies systematically across professional groups (business, government, civil society).

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Global Risks and Challenges to Contemporary Global Security

- S—Security:

- ▪

- cybersecurity ranks 4th in the 2-year outlook and 8th in the 10-year horizon, highlighting the persistent nature of threats in the digital environment;

- ▪

- involuntary migration, ranked 8th in the short term and rising to 7th in the long term, demonstrates how population security is closely linked to geopolitical instability and environmental crises;

- ▪

- interstate armed conflict (ranked 5th in the short term) indicates that traditional threats to national and international security remain relevant.

- E—Environmental:

- ▪

- in the 10-year outlook, all of the top four risks are environmental in nature: extreme weather events, critical changes to Earth systems, biodiversity loss, and resource scarcity;

- ▪

- this underscores the dominance of the environmental dimension in long-term understandings of security—as a foundation of societal resilience.

- S—Social:

- ▪

- misinformation and disinformation top the list of short-term threats (ranked 1st for the 2-year horizon) and remain significant in the long-term (5th place). This reflects the systemic threat posed by informational vulnerability to democratic processes;

- ▪

- societal polarization is another critical social risk appearing in both rankings. It destabilizes political systems and undermines trust in institutions.

- G—Governance:

- ▪

- lack of economic opportunity, inflation, and economic downturn represent governance-related risks with strong short-term impact;

- ▪

- in the 10-year horizon, the emergence of “adverse outcomes of AI technologies” points to a new challenge for regulatory frameworks, requiring innovative approaches to technology governance—a core component of the “G” pillar.

3.2. Evolution of ESG—From the Traditional Model to S + ESG

- ▪

- S (Security): ensuring not only physical but also digital and humanitarian protection;

- ▪

- E (Environmental): recognizing nature as a determinant of survival;

- ▪

- S (Social): addressing polarization and fostering social cohesion;

- ▪

- G (Governance): emphasizing the need for adaptive, transparent, and technologically competent governance.

- ▪

- UAH 300 million—electronic warfare systems (Nova Poshta, 2024) [20];

- ▪

- UAH 100 million—demining (Kyivstar, 2024) [21];

- ▪

- UAH 50 million—unmanned platforms (WOG, 2024) [22];

- ▪

- UAH 48 million—mobile UAV control centers (1 + 1 media, 2024) [23];

- ▪

- UAH 33 million—drone operator training (PrivatBank, 2024) [24];

- ▪

- UAH 20 million—communication equipment for army aviation (Podorozhnyk, 2024) [25];

- ▪

- UAH 20 million—steel shelters (Metinvest, 2024) [26];

- ▪

- UAH 15 million—air defense communication complexes (Ribas Hotels, 2024) [27].

- ▪

- Investors view security risks as a key component of business resilience;

- ▪

- Consumers expect companies to prioritize their safety and well-being;

- ▪

- Regulators may impose fines for neglecting safety standards;

- ▪

- Employees seek employers who guarantee safe and secure working conditions.

3.3. Research Findings

- Respondent profile:

- ▪

- Age distribution: The majority of respondents (43.4%) are aged 40–49. This indicates the involvement of an experienced audience, potentially engaged in managerial or strategic processes.

- ▪

- Fields of activity: Over 50% of participants identified themselves as representatives of business or entrepreneurship, which is highly relevant in the context of assessing the perception of the SESG model specifically in the private sector.

- Level of awareness:

- ▪

- 88% of respondents perceive sustainable development as a balance between economic growth, environmental protection, and social welfare, indicating a mature understanding of the concept.

- ▪

- At the same time, only 10.8% stated they are “fairly familiar” with ESG, and 14.5% are studying or researching it in depth. This reveals a gap between general awareness of sustainable development and understanding of ESG as a concrete tool, especially in the context of security.

- Support for the SESG concept:

- ▪

- 65.1% believe that integrating security into ESG is a logical evolution, and another 25.3% support it “but only in specific countries”. Thus, over 90% support the SESG concept in some form.

- ▪

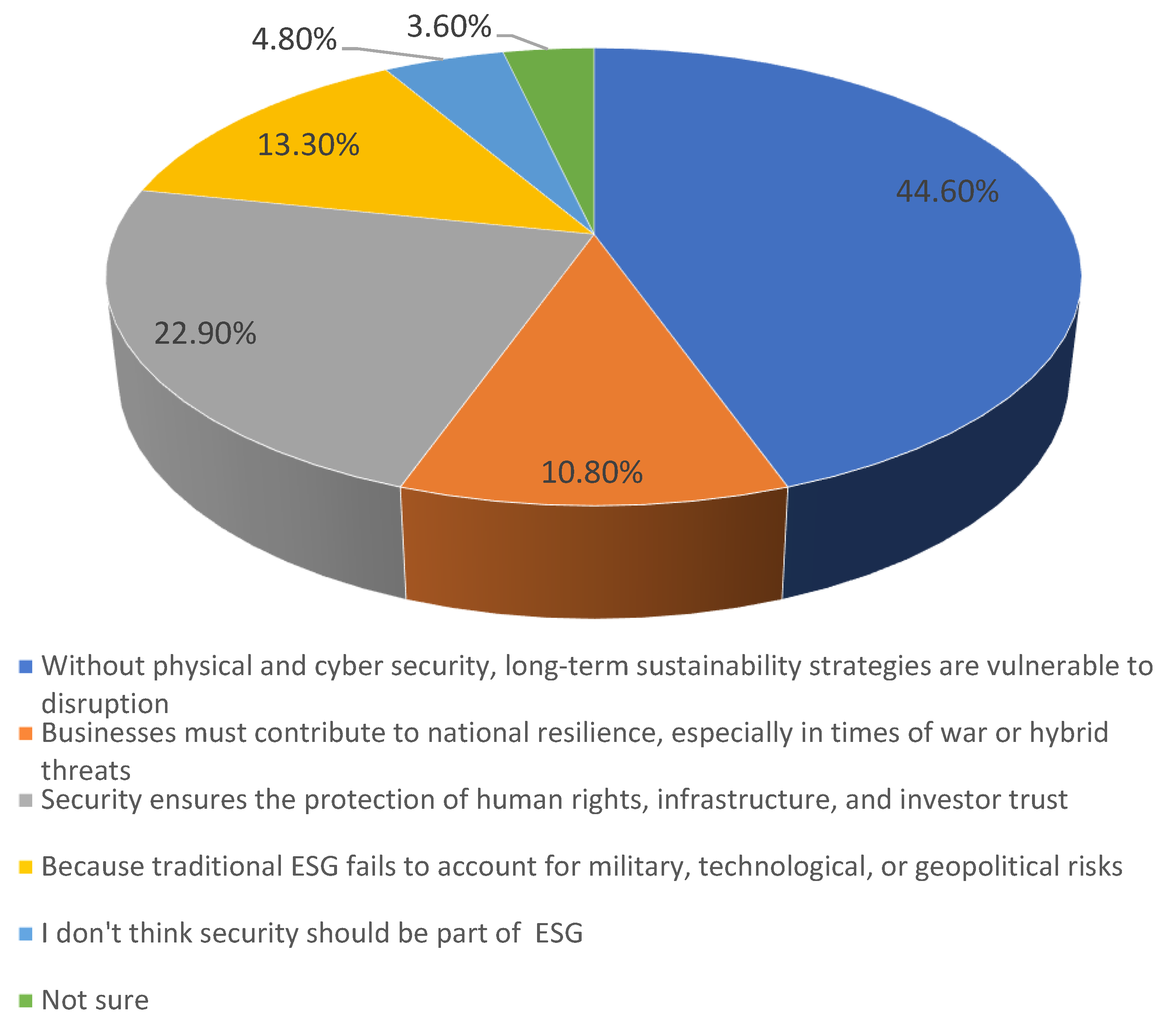

- The main reason for emphasizing the security factor within ESG was that “without physical and cyber security, long-term sustainability strategies are impossible” (44.6%), followed by protection of human rights, infrastructure, and investor trust (22.9%).

- Business role and model potential:

- ▪

- 56.6% of respondents view the role of private business in the defense and security sector as extremely important, with another 39.8% seeing it as “positive, though not decisive”.

- ▪

- 63.9% believe that SESG is a timely and necessary new standard for sustainable business development in Ukraine. Only 6% consider the model irrelevant or outdated.

- 0—No policy or practice in place

- 1–2—Basic implementation or work-in-progress

- 3–4—Functional system with signs of regularization

- 5—Full integration, subject to continuous updates and external verification

- ▪

- conduct pilot testing in companies across different industries;

- ▪

- align with international standards such as ISO 45001, ISO 27001, GRI, SASB [5];

- ▪

- adapt to sector-specific risks, since threats in IT, energy, and manufacturing differ significantly.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- H1: The hypothesis that security considerations are perceived by stakeholders as equally or more important than traditional ESG components in fragile and conflict-affected contexts is confirmed. Over 90% of respondents supported the integration of security as a distinct pillar within ESG.

- H2: The hypothesis that integrating security into the ESG framework (SESG) significantly enhances its ability to capture resilience-related challenges is confirmed. The SESG model offers a comprehensive response to new types of risks that are not fully addressed by the traditional ESG framework.

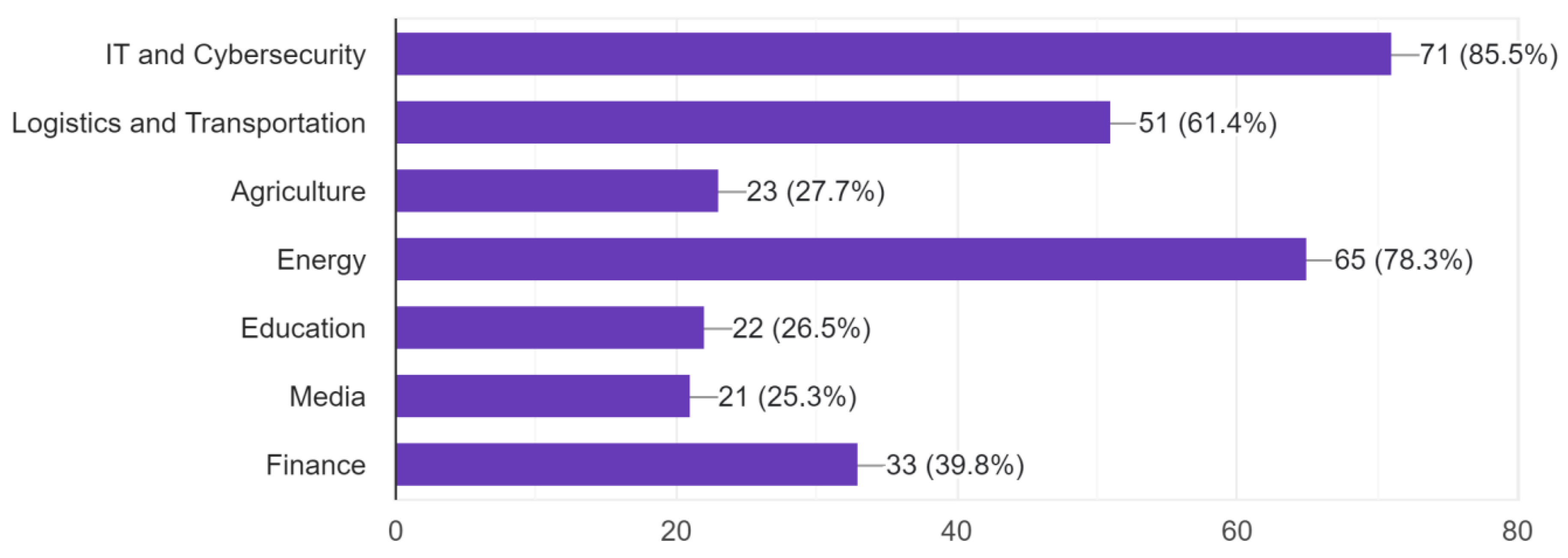

- H3: The hypothesis that the prioritization of security within sustainability strategies varies systematically across professional groups is partially confirmed. The highest levels of support for SESG were observed among respondents from business and government sectors, whereas lower engagement was recorded in sectors such as media and education.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene: Demanding Greater Solidarity. 2022. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3958751?v=pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2024, 19th ed.; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 10 January 2024; Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2025, 20th ed.; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 15 January 2025; Available online: https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2025.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Barbosa, A.d.S.; Crispim da Silva, M.C.B.; Bueno da Silva, L.; Morioka, S.N.; de Souza, V.F. Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria: Their Impacts on Corporate Sustainability Performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Behind ESG Ratings: Unpacking Sustainability Metrics. 2025. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/02/behind-esg-ratings_4591b8bb/3f055f0c-en.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Humenna, O.V.; Shchur, D.V. The Evolution of ESG: The Role of Security in Business Sustainable Development under Global Threats. In Management and Marketing as Factors of Business Development: Proceedings of the III International Scientific-Practical Conference; Khrapkina, V.V., Pichyk, K.V., Eds.; Publishing House “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy”: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2025; Volume 2, p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, S.; Springsteel, A. The Value and Current Limitations of ESG Data for the Security Selector. J. Environ. Investig. 2017, 8, 54–73. Available online: https://www.thejei.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Journal-of-Environmental-Investing-8-No.-1.rev_-1.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Horlinskyi, V.V. Philosophy of Security and Sustainable Human Development: Value Dimension (Monograph). Parapan Publishing: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2011; Available online: https://ela.kpi.ua/server/api/core/bitstreams/1e76778a-68ce-4fb7-9738-72a625094944/content (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Antoniuk, L.; Humenna, O.; Poruchnyk, A.; Taruta, S.; Kharlamova, H.; Chala, N. White Paper of Ukraine’s Economic Policy Until 2030: National and Regional Dimensions; Pavlenko: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P. Employers Face a Rising Climate Conundrum. Financial Times, 2 June 2024. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/810ab310-a6cb-486d-a942-9b103d68fc48/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Gaines, C. Millennials and Gen Z Are Giving Up on One of Their Core Values and Investing More like Boomers. Business Insider. 11 January 2024. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/esg-investing-strategies-millennials-gen-z-baby-boomers-compabnies-funds-2024-1 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Deloitte. Future of ESG Reporting Under Geopolitical Stress. 2024. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/services/audit-assurance/articles/esg-survey.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- European Commission. Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). 2023. Available online: https://www.corporate-sustainability-due-diligence-directive.com/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Bruno, E.; Pistolesi, F.; Teti, E. Cybersecurity policy, ESG and operational risk: A Virtuous relationship to improve banks’ performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 99, 104053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasinovych, I.; Myskiv, G. Ukrainian context of sustainable development and the role of business in its achievement. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sáenz, E.; Medina-Quintero, J.M.; Reyna-Castillo, J. Cybersecurity and ESG: Foundations of Business Stability in the Digital Era. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, R. Safeguarding Enterprises from Cyber Risk with ESG. ISACA J. 2023, 6. Available online: https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues/2023/volume-6/safeguarding-enterprises-from-cyberrisk-with-esg (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Heil, P.; Höslinger, E.A.; Potrafke, N.; Tähtinen, T. Economic Experts Survey Q1 2025; IFO Institute: Munich, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Humenna, O.; Bedii, N. Impact Entrepreneurship and ESG Strategy as an Effective Alternative to CSR for Companies to Create Positive Impact. Sci. Notes Nauk. Ser. Econ. Sci. 2024, 9, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nova Post. REBnemo Tak REBnemo: Nova Poshta and Come Back Alive Launched a 300 Million UAH Fundraiser for Air Defense Strengthening. 2024. Available online: https://savelife.in.ua/materials/news/rebnemo-tak-rebnemo-povernys-zhyvym-i-no/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Kyivstar. We Live Here: Kyivstar and Come Back Alive Launched a Charity Project. 2024. Available online: https://kyivstar.ua/safehome (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- WOG. WOGON OF HELP: Collecting a Robot Squad. 2024. Available online: https://wog.ua/ua/news-detail/wogon-dopomogy-zbyrayemo-zagin-robotiv/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- 1+1 Media. 1+1 Media, Come Back Alive, and UPL Launch “Drone League 3.0” to Raise UAH 48 Million for Mobile UAV Command Points. 2024. Available online: https://media.1plus1.ua/news/11-media-povernis-zivim-i-upl-zapuskaiut-projekt-liga-aerorozvidki-30-shhob-zibrati-48-mln-grn-na-mobilni-punkti-upravlinnia-bpak (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- PrivatBank. Fundraiser for the Opening of UAV School: Preparing Unmanned Aviation Specialists. 2024. Available online: https://privatbank.ua/cpa/yatagan (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Podorozhnyk. Formula of Communication. 2024. Available online: https://podorozhnyk.ua/promotions/formula-zvyazku/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Metinvest. 1000 Days of War: Metinvest Allocated UAH 8 Billion to Support Ukraine. 2024. Available online: https://surl.li/bqfypo (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Ribas Hotels. Love? Donate!—Ribas Hotels Charity Initiative. 2024. Available online: https://donate.ribas.ua/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- OKKO. All 10 Pullstron Complexes Handed Over to Airborne Assault Units as Part of OKO ZA OKO Initiative. 2025. Available online: https://www.okko-group.com.ua/en/novunu/holding-news/okko-i-povernis-zhivim-peredali-desantnikam-zbroiu-i-tekhniku-na-500-mln-grn-vona-uzhe-nishchit-voroga (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Versace, C.; Abssy, M. How Millennials and Gen Z Are Driving Growth Behind ESG. Nasdaq. 23 September 2022. Available online: https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/how-millennials-and-gen-z-are-driving-growth-behind-esg (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Wikipedia. Political Views of Generation Z. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_views_of_Generation_Z (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Vorecol Editorial Team. How Do Different Generations Perceive Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Influence on Work Environment? Vorecol Blog. 28 October 2024. Available online: https://blogs.vorecol.com/blog-how-do-different-generations-perceive-corporate-social-responsibility-and-its-influence-on-work-environment-202449 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- KPMG. Cybersecurity in ESG: Building Trust in a Digital World. 2023. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2023/08/cybersecurity-in-esg.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Shah, S.Q.A.; Lai, F.W.; Shad, M.K.; Hamad, S.; Ellili, N.O.D. Exploring the effect of enterprise risk management for ESG risks towards green growth. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 74, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Does Cybersecurity Deserve Its Own Pillar in ESG Frameworks? 2022. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/11/14/esg-and-c-does-cybersecurity-deserve-its-own-pillar-in-esg-frameworks/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Sekol, M. ESG Mindset: Business Resilience and Sustainable Growth; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arangil, A. An ESG Enhanced-Agile Corporate Governance Framework for Better Business Resilience amid Uncertainty. Issue 2 Int’l JL Mgmt. Hum. 2022, 5, 1561. [Google Scholar]

- De Giuli, M.E.; Grechi, D.; Tanda, A. What do we know about ESG and risk? A systematic and bibliometric review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Main Topic/Contribution | Key Findings/Relevance to SESG |

|---|---|---|

| Horlinskyi, V. (2011) [8] | Security as a value-based dimension of sustainable development | Argues that security is a core condition of sustainability |

| Antoniuk et al. (2018) [9] | A systemic security model for Ukraine | Expands the definition of security: infrastructure, social, informational |

| UNDP (2022) [1] | Human security in the Anthropocene | Security as human-planet interdependence |

| World Economic Forum (2024) [2] | Global risks: cyber threats, climate instability | Rising pressure on ESG from global systemic risks |

| OECD (2025) [5] | ESG ratings and risk assessment gaps | ESG neglects critical security risks in conflict zones |

| Barbosa et al. (2023) [4] | ESG and corporate resilience | Security is integral to ESG in fragile regions |

| Humenna & Shchur (2025) [6] | SESG as a new paradigm | Advocates integrating security into ESG amid hybrid threats |

| Bose & Springsteel (2017) [7] | Limits of ESG data in security contexts | Current metrics overlook aggression and disinformation |

| Clark, P. (2024) [10] | Climate risks for employers | ESG must be adapted to extreme scenarios |

| Gaines, C. (2024) [11] | ESG perceptions among Gen Z and Millennials | Young generations increasingly critical of “ineffective ESG” |

| Deloitte (2024) [12] | Future of ESG Reporting under Geopolitical Stress | Recommends ESG adaptation to geopolitical security risks |

| European Commission (2023) [13] | Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) | Introduces legal obligations for addressing human rights and security in ESG |

| Rank | Global Risks (2-Year Outlook) | Rank | Global Risks (10-Year Outlook) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Misinformation and Disinformation | 1 | Extreme Weather Events |

| 2 | Extreme Weather Events | 2 | Critical Changes to Earth Systems |

| 3 | Societal Polarization | 3 | Biodiversity Loss and Ecosystem Collapse |

| 4 | Cyber Insecurity | 4 | Natural Resource Shortages |

| 5 | Interstate Armed Conflict | 5 | Misinformation and Disinformation |

| 6 | Lack of Economic Opportunity | 6 | Adverse Outcomes of Artificial Intelligence |

| 7 | Inflation | 7 | Involuntary Migration |

| 8 | Involuntary Migration | 8 | Cyber Insecurity |

| 9 | Economic Downturn | 9 | Societal Polarization |

| 10 | Pollution | 10 | Pollution |

—Environmental

—Environmental  —Technological

—Technological  —Economic

—Economic  —Geopolitical

—Geopolitical  —Social.

—Social.| Maslow’s Level of Needs | SESG Components | Corporate Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Physiological Needs | Security, Environmental | Ensuring basic resources: electricity, water, heat, food security, resilient infrastructure. |

| 2. Safety and Security | Security, Governance | Investments in national security, cyber defense, military support, transparent governance, legal stability. |

| 3. Social Belonging | Social, Security | Support for employees, communities, IDPs (internally displaced persons); volunteering; wartime social initiatives. |

| 4. Esteem and Recognition | Governance, Social, Security | Building a reputation as a responsible business, leadership in SESG, participating in standard-setting. |

| 5. Self-Actualization | SESG (all components integrated) | Achieving higher goals: sustainable development, innovation, defending democracy, strategic societal transformation. |

| Generation | Birth Years | Attitude Toward Sustainability | Perception of Security | Examples of Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silent Generation | Before 1945 | Views sustainability primarily as an ethical issue, with a focus on social responsibility | Security = protection and stability; institutional security is key | Supporting community organizations, engaging in veteran initiatives |

| Baby Boomers | 1946–1964 | Often see ESG as an external trend but acknowledge its importance, especially shaped by crisis experience | Emphasis on physical and economic security; skeptical of newer risks (e.g., cybersecurity) | Philanthropy, voting for green initiatives, investing in stable ESG funds |

| Generation X | 1965–1980 | Takes a pragmatic approach: supports sustainability through efficiency and risk management | Understands the link between security and risks to business and family | Supporting local projects, ESG investing, workplace sustainability implementation |

| Millennials (Y) | 1981–1996 | Among the most active on environmental, human rights, and transparency issues | Broad view of security: includes cyber, mental health, and community safety | Activism, choosing “green” brands, participating in digital safety campaigns |

| Generation Z | 1997–2012 | Treat ESG as a life standard; focused on systems thinking and social justice | Security = trust, privacy, psychological comfort; least trust in institutions | Online activism, brand boycotts, promoting cyber ethics |

| Generation Alpha | 2013+ | Still developing; shaped by their environment | Expected to integrate ESG deeply in school education; security as a default norm | Education, digital platforms with embedded ESG logic |

| Dimension | Indicator | Type | Sample Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Security | Number of incidents per 100 employees | Quantitative | 2 incidents/100 |

| Cybersecurity | Existence of a cybersecurity policy | Qualitative | Yes/No |

| Psychological Safety | Employee satisfaction level | Quantitative | 75% positive responses |

| Social Security | Presence of a crisis action plan | Qualitative | Available/Not available |

| Dimension | Subcategory | Indicator/Assessment Question | Type | Score (0–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S—Social | Occupational Safety | Existence of workplace safety system (e.g., ISO 45001 [32], audits) | Qualitative | |

| Employee Wellbeing | Mental health and stress-management programs | Qualitative | ||

| Equality and Non-discrimination | Diversity & Inclusion policy in place | Qualitative | ||

| Community Engagement | Social projects, feedback mechanisms | Qualitative | ||

| E—Environmental | Resource Consumption | Water and energy audits | Quantitative | |

| CO2 Emissions | Emissions per production unit | Quantitative | ||

| Waste Management | Recycling and disposal systems in operation | Qualitative | ||

| S—Security | Physical Security | Security protocols for personnel and assets | Qualitative | |

| Cybersecurity | Presence of ISO 27001/SOC 2 [33]; number of incidents | Mixed | ||

| Psychological Safety | Survey on perceived workplace safety culture | Quantitative | ||

| Crisis Preparedness | Emergency response plans; staff drills | Qualitative | ||

| G—Governance | Anti-Corruption Policy | Is an anti-corruption policy in force? | Qualitative | |

| Reporting Transparency | Is an ESG/SESG report publicly available? | Qualitative | ||

| Strategic Integration of Security | Is “security” referenced in the mission or KPIs? | Qualitative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kharlamova, G.; Shchur, D.; Humenna, O. S + ESG as a New Dimension of Resilience: Security at the Core of Sustainable Business Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188425

Kharlamova G, Shchur D, Humenna O. S + ESG as a New Dimension of Resilience: Security at the Core of Sustainable Business Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188425

Chicago/Turabian StyleKharlamova, Ganna, Denys Shchur, and Oleksandra Humenna. 2025. "S + ESG as a New Dimension of Resilience: Security at the Core of Sustainable Business Development" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188425

APA StyleKharlamova, G., Shchur, D., & Humenna, O. (2025). S + ESG as a New Dimension of Resilience: Security at the Core of Sustainable Business Development. Sustainability, 17(18), 8425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188425