Using the Adaptive Cycle to Revisit the War–Peace Trajectory in Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review on the Analytical Framework

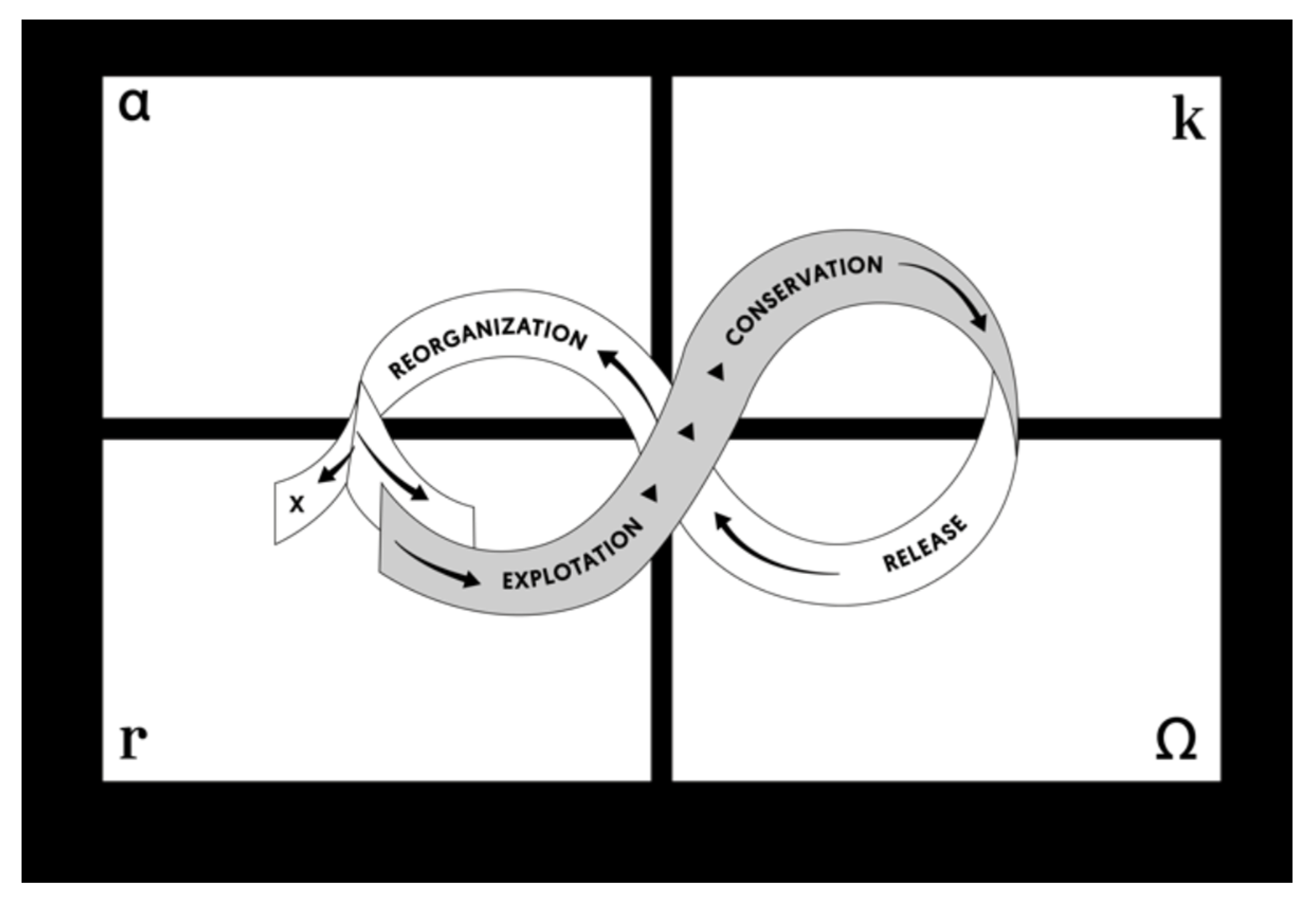

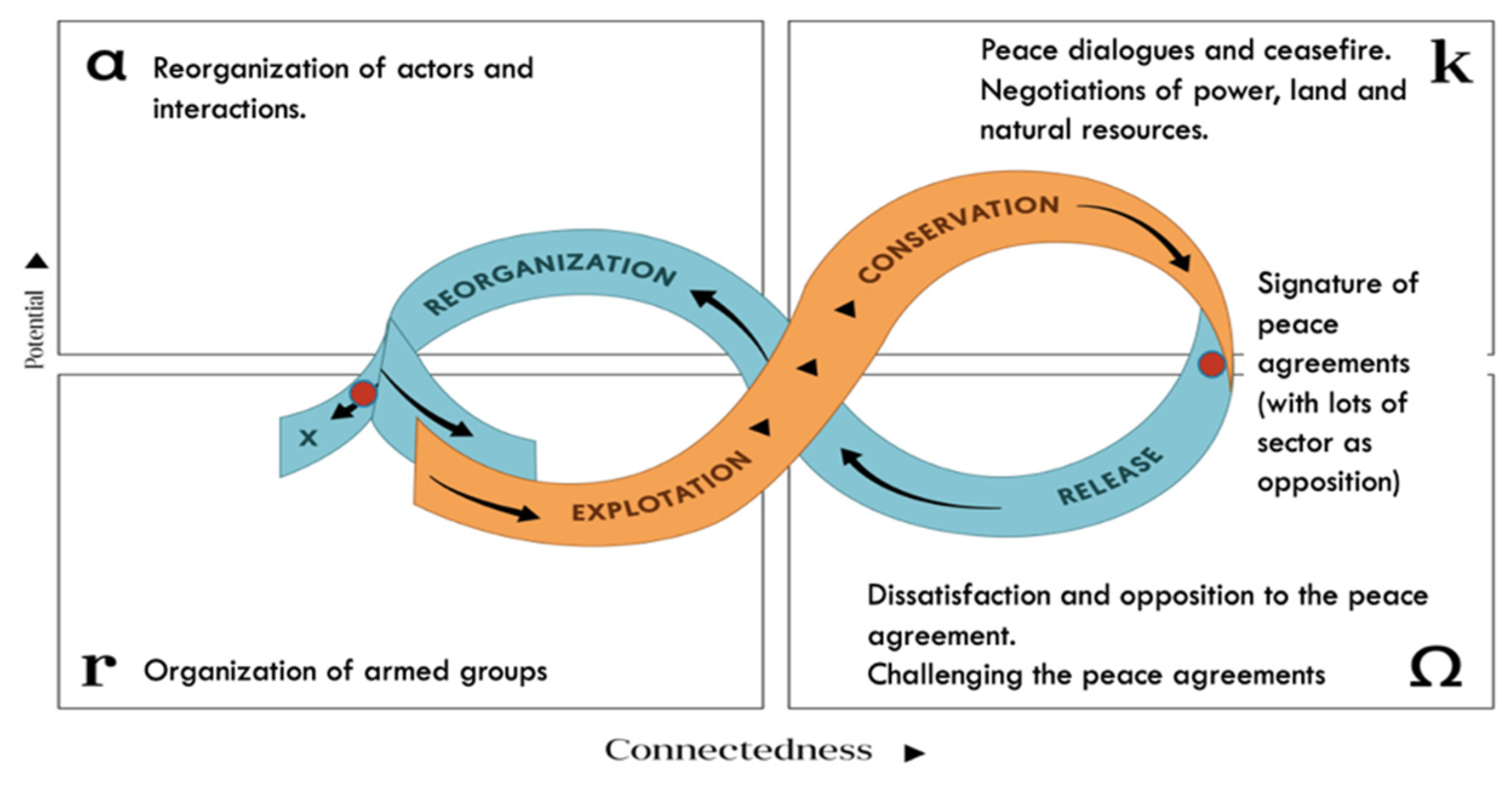

2.1. The Adaptive Cycle

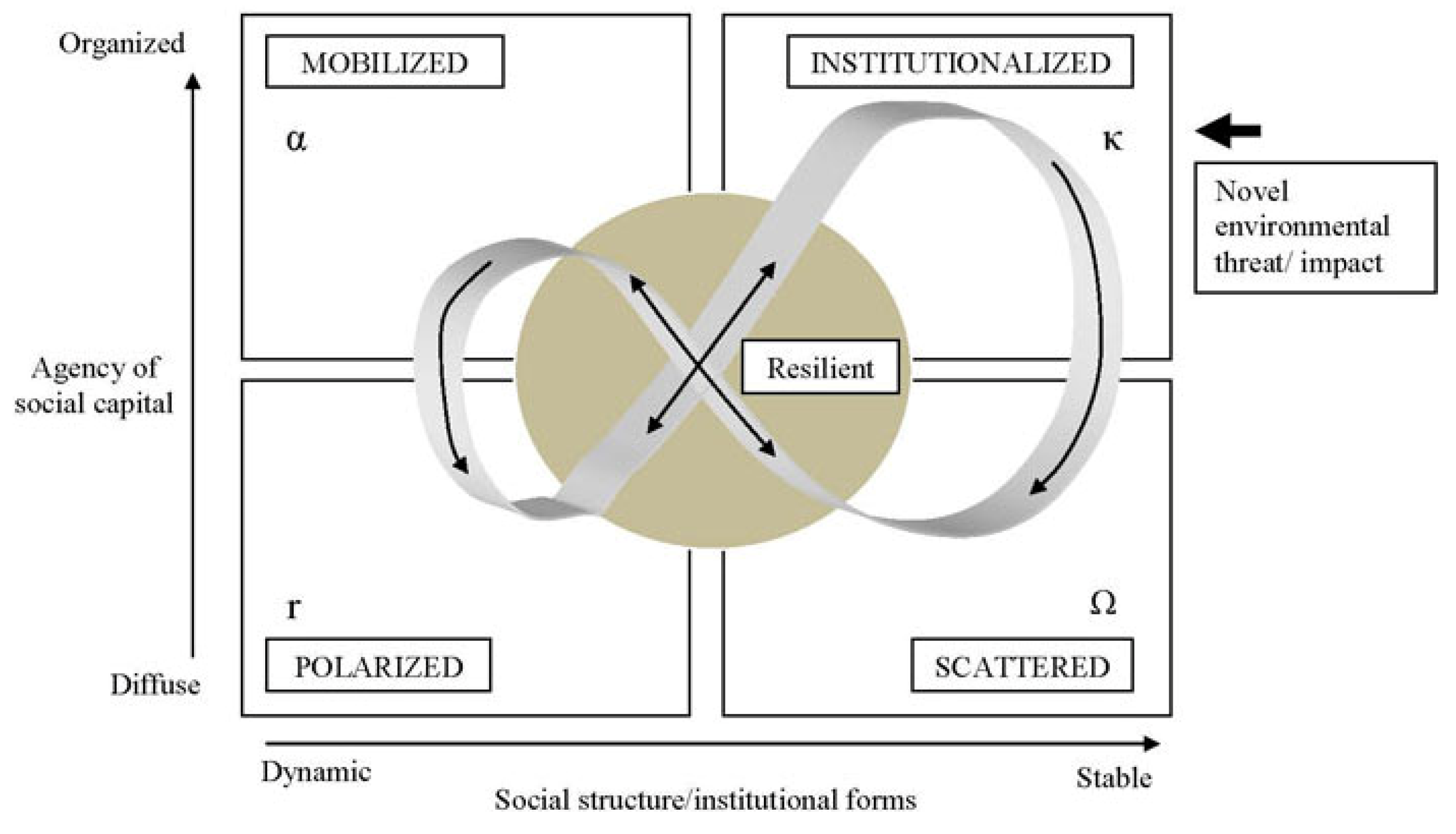

2.2. Resilience, Adaptive Cycle, and War/Peace

3. Materials and Methods

- Exploitation (r): Rapid emergence of new armed actors or coalitions, fragmentation, and fluid actor dynamics; opportunistic violence and initial territorial expansion.

- Conservation (K): Stabilization of dominant groups, institutionalization of violence, limited emergence of new actors, and high connectivity in actor networks.

- Collapse (Ω): Breakdown of dominant regimes due to delegitimization or strategic defeat; increasing unpredictability; fragmentation and demobilization.

- Reorganization (α): Formation of new actor constellations, formal negotiations or reintegration programs, weak but emerging forms of order.

4. Results

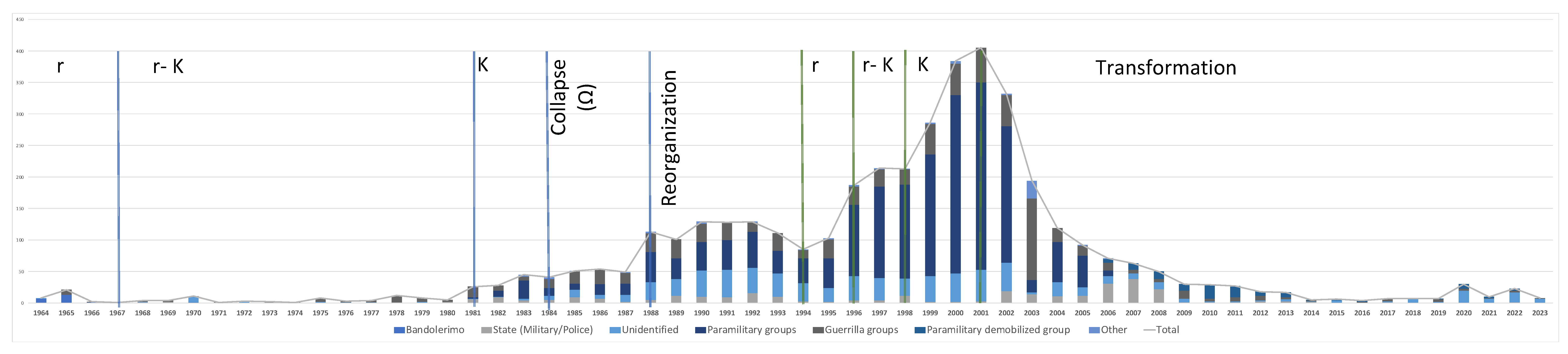

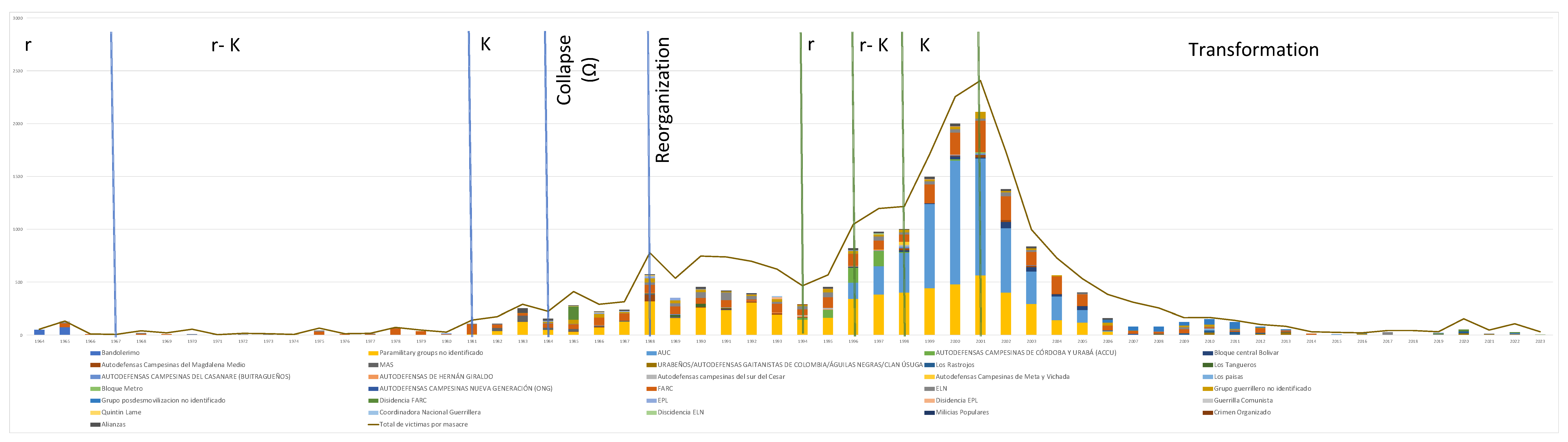

4.1. First Cycle in the Counterinsurgency War: 1964–1995

4.1.1. Exploitation (r) (1964–1967)

4.1.2. Transition Between Exploitation (r) and Conservation (K) (1968–1980)

4.1.3. Late Conservation (K) Phase (1981–1983)

4.1.4. Collapse/Release (Ω) Phase (1984–1987)

4.1.5. Reorganization (α) Phases (1988–1994)

4.2. Second Cycle in the Counterinsurgency War: 1995–2023

4.2.1. Exploitation Phase (r) 1995–1996

4.2.2. Transition Between the Exploitation (r) and Conservation (K) Phases (1997–1998)

4.2.3. Late Conservation Phase (K) (1999–2001)

4.2.4. System Transformation (2001–2023)

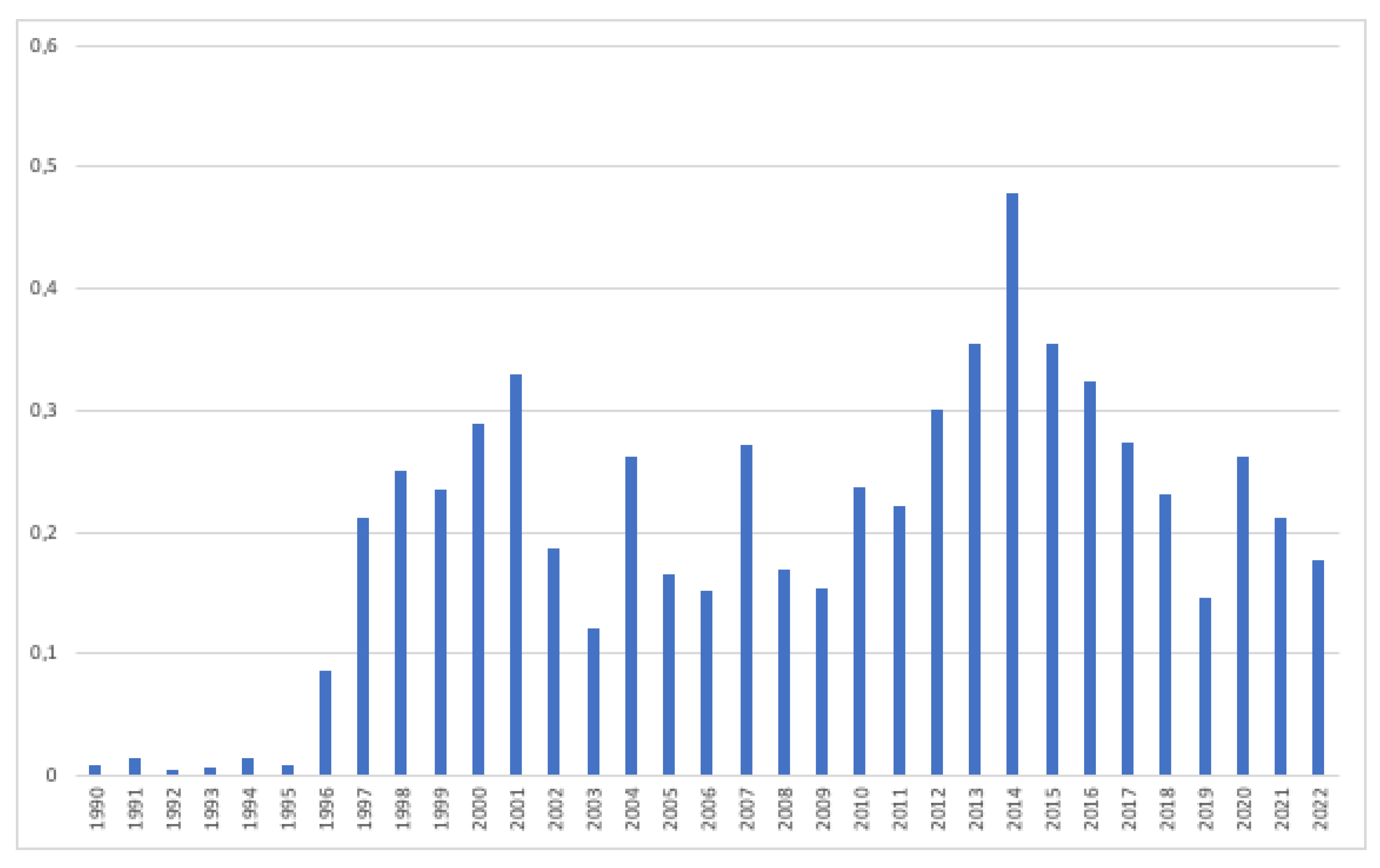

4.3. Deforestation Trajectory

5. Discussion

5.1. War as a Regular Regime, Peace as a Collapse of This Regime

5.2. War/Peace and Deforestation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNG | Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera |

| CONVIVIR | Cooperativas de Vigilancia y Seguridad Privada para la Defensa Agraria |

| ELN | Ejército de Liberación Nacional |

| EPL | Ejército Popular de Liberación |

| FARC | Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia |

| IDEAM | Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales de Colombia |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre |

| SES | Social-Ecological System |

Appendix A

| War Cycle | Cycle Phase | Total Number of Actors | Name of Actors | Phase Dynimics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Counterinsurgency War Cycle (1964–1995) | Exploitation (r) (1964–1967) | 4 | Bandolerismo Guerrilla Comunista, FARC, ELN | During this phase, three new actors emerge in the aftermath of La Violencia. At the onset of the exploitation phase, Bandolerismo—a remnant of La Violencia—becomes the primary actor in the conflict. During this period, the FARC and ELN guerrillas consolidate. A small number of massacres are reported during this phase, with the majority attributed to Bandolerismo. The FARC and ELN also participate, though to a lesser extent. |

| Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | 4 | Bandolerismo FARC ELN EPL | During this phase, actors consolidate their existence and their bonds while one actor, a remnant of the previous war, disappears. Banditry ceases to exist as an actor, while guerrilla groups such as the FARC, ELN, and EPL strengthen their positions. | |

| Late conservation (K) phase (1981–1983) | 4 | FARC ELN EPL MAS (paramilitary) | At the end of the exploitation phase, massacres show a significant increase, accompanied by the emergence of one new perpetrator group: in response to the violence generated by guerrilla groups, the paramilitary organization Muerte a los Secuestradores (Death to Kidnappers, MAS) emerged. During this phase, actors are interconnected through acts of violence. Both the number of massacres and the involvement of various actors rise. | |

| Collapse/release (Ω) phase (1984–1987) | 9 | FARC ELN EPL FARC dissidences, Quintin Lame, Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera MAS : Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena, Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo | During this period of peace efforts, drug trafficking and paramilitary groups expanded their involvement in massacres. Dissidents from the Farc emerged, indigenous guerilla Quintin Lame and una coordination nacional de la guerilla was also created New paramilitary groups, such as the Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena and those led by Hernán Giraldo, emerged. During this phase, the number of massacres and victims slightly increased. The penalties were distributed in all groups, showing that no group was dominant. | |

| Transition between first cycle and second cycle | Reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | 18 | FARC ELN EPL Quintin Lame Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera New: EPL Dissidences ELN Dissidences FARC Dissidences Milicias Populares MAS— Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo New: Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Los Tangueros (disappears) Bloque Central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Campesinas del Sur del Cesar Crimen Organizado | During the reorganization phase, there is a significant but unstable increase in massacres, accompanied by a reorganization of the actors involved. On one hand, several guerrilla groups, such as the M19, EPL, Quintín Lame, parts of the FARC, and the ELN, were demobilized. On the other hand, new paramilitary groups emerged, including the Tangueros, the Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare, the Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio, the Autodefensas Campesinas del Sur del Cesar, and the Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urabá. Additionally, some structures of the FARC and the ELN persisted, while a dissidence of the EPL was formed. Other actors, such as the Popular Militias, the Tangueros, and Organized Crime, also appeared and disappeared during this phase. This shift in actors is reflected in the fluctuating nature of violence during this period. Nevertheless, the overall number of massacres continued to rise. |

| Second cycle of the Counterinsurgency War (1995–present) | Exploitation phase (r) (1995–1996) | 11 | FARC ELN EPL Dissidences ELN Dissidences Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Bloque Central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Campesinas del Sur del Cesar New: Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia -AUC- | This phase witnessed a renewed increase in massacres and the consolidation of new paramilitary groups, including the formation of the AUC in 1995. In contrast, the guerrillas were reduced to the FARC, the ELN, the EPL and the dissidents from ELN and EPL. |

| Transition between the exploitation (r) and conservation (K) phases (1997–1998) | 12 | FARC ELN EPL Dissidences ELN Dissidences) Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Bloque Central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Campesinas del Sur del Cesar Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia—AUC- New: Autodefensas Campesinas de Meta y Vichada (disappears) | In this phase, there is a notable increase in massacres carried out by paramilitary groups. During this period, two paramilitary groups disbanded. | |

| Late conservation phase (K) (1999–2001) | 10 | FARC ELN EPL Dissidences (disappears) Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Bloque Central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia—AUC- New: Bloque Metro | During this phase, the increase in massacres is exponential. | |

| System transformation (2001–2023) | 8 | FARC ELN Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Bloque Central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia—AUC- | During the early collapse phase, massacres decrease, and the disappearance of paramilitary groups begins. Álvaro Uribe initiated a demobilization process for the paramilitary groups through the Santa Fe de Ralito Agreement of 2003. This is immediately followed by system transformation. | |

| 14 | FARC (disappears) ELN New: FARC Dissidences Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) (disappears) Bloque Central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia -AUC- (disappears) New: Urabeños Rastrojo Los paisas ONG Grupos desmobilizados | The system underwent a transformation, with paramilitary groups disappearing between 2003 and 2007. Following this, there was instability among the actors, as paramilitary dissidents reorganized into organized crime groups. In this context, with the paramilitary groups disbanded and guerrilla activity largely controlled by the State, a peace agreement was signed in 2016 between the FARC and the government. As a result, only the ELN and dissident groups remained from the previous cycle. These dissident groups are primarily linked to narcotrafficking and organized crime, and their violent practices are no longer primarily massacres—although massacres did increase again in 2019. However, the key conclusion is that the counterinsurgency war ended, giving way to a new conflict with distinct characteristics: less political in nature and driven by a net interest in territorial control linked to narcotrafficking and organized crime. |

Appendix B

| Year | Adaptive Cycle Phase | Armed Actors Identified | Total Actors | New Actors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Bandolerimo | 1 | 0 | |

| 1964 | Exploitation (r) (1964–1967) | Bandolerimo | 1 | 0 |

| 1965 | Exploitation (r) (1964–1967) | Bandolerimo Guerrilla Comunista FARC ELN | 4 | 3 |

| 1966 | Exploitation (r) (1964–1967) | Bandolerimo FARC | 2 | 0 |

| 1967 | Exploitation (r) (1964–1967) | 0 | 0 | |

| 1968 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 1969 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC | 1 | 0 |

| 1970 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | Bandolerimo ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 1971 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | ELN | 1 | 0 |

| 1972 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | ELN | 1 | 0 |

| 1973 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | ELN | 1 | 0 |

| 1974 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | Grupo guerrillero no identificado | 1 | 0 |

| 1975 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 1976 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC | 1 | 0 |

| 1977 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 1978 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 1979 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC | 1 | 0 |

| 1980 | Transition between exploitation (r) and conservation (K) (1968–1980) | FARC EPL | 2 | 1 |

| 1981 | Late conservation (K) phase (1981–1983) | Paramilitary groups no identificado FARC ELN | 3 | 1 |

| 1982 | Late conservation (K) phase (1981–1983) | MAS FARC EPL | 3 | 1 |

| 1983 | Late conservation (K) phase (1981–1983) | MAS FARC | 2 | 0 |

| 1984 | Collapse/release (Ω) phase (1984– 1987) | MAS FARC ELN EPL | 4 | 0 |

| 1985 | Collapse/release (Ω) phase (1984–1987) | Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio MAS FARC ELN Disidencia FARC Quintin Lame | 5 | 3 |

| 1986 | Collapse/release (Ω) phase (1984–1987) | Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio MAS Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo FARC EPL Quintin Lame | 6 | 0 |

| 1987 | Collapse/release (Ω) phase (1984–1987) | MAS FARC ELN EPL Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera | 5 | 1 |

| 1988 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Los Tangueros Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio MAS Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo FARC ELN EPL Quintin Lame | 8 | 1 |

| 1989 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Los Tangueros MAS Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) FARC ELN EPL | 6 | 1 |

| 1990 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Los Tangueros Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio FARC ELN EPL | 5 | 0 |

| 1991 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Los Tangueros Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas Campesinas del sur del Cesar FARC | 5 | 1 |

| 1992 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo FARC ELN Disidencia EPL Milicias Populares | 6 | 3 |

| 1993 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo FARC ELN Disidencia EPL Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera | 6 | 0 |

| 1994 | Transition between the release (Ω) and the reorganization (α) phases (1988–1994) | Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba Y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas del sur del Cesar FARC ELN Crimen Organizado | 7 | 2 |

| 1995 | Exploitation phase (r) 1995–1996 | Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo FARC ELN Disidencia EPL | 6 | 0 |

| 1996 | Exploitation phase (r) 1995–1996 | AUC Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas Campesinas del sur del Cesar FARC ELN EPL | 8 | 1 |

| 1997 | Transition between the exploitation (r) and conservation (K) phases (1997–1998) | AUC Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo Autodefensas Campesinas de Meta y Vichada FARC Disidencia ELN | 7 | 1 |

| 1998 | Transition between the exploitation (r) and conservation (K) phases (1997–1998) | AUC Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá (ACCU) Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) Autodefensas Campesinas de Meta y Vichada Autodefensas Campesinas del sur del Cesar FARC ELN | 9 | 0 |

| 1999 | Late conservation phase (K) (1999–2001) | AUC Bloque central Bolivar FARC ELN Disidencia EPL | 5 | 0 |

| 2000 | Late conservation phase (K) (1999–2001) | AUC Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba Y Urabá (ACCU) Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio AUTODEFENSAS CAMPESINAS DEL CASANARE (BUITRAGUEÑOS) Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo FARC ELN Disidencia EPL | 9 | 0 |

| 2001 | Late conservation phase (K) (1999–2001) | AUC Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio AUTODEFENSAS CAMPESINAS DEL CASANARE (BUITRAGUEÑOS) Bloque Metro FARC ELN | 8 | 0 |

| 2002 | Transformation | AUC Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio FARC ELN | 5 | 0 |

| 2003 | Transformation | AUC Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) FARC ELN | 6 | 0 |

| 2004 | Transformation | AUC Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio FARC Grupo guerrillero no identificado | 5 | 1 |

| 2005 | Transformation | AUC Bloque central Bolivar Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio FARC ELN | 5 | 0 |

| 2006 | Transformation | AUC FARC Grupo posdesmovilizacion no identificado | 3 | 1 |

| 2007 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrojos Autodefensas Campesinas Nueva Generación (ONG) FARC | 4 | 3 |

| 2008 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrojos FARC ELN | 4 | 0 |

| 2009 | Transformation | Los Rastrojos FARC ELN | 3 | 0 |

| 2010 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrojos Los Paisas FARC ELN | 5 | 0 |

| 2011 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrojos FARC ELN | 4 | 0 |

| 2012 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrojos FARC | 3 | 0 |

| 2013 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrojos FARC ELN | 4 | 0 |

| 2014 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga FARC | 2 | 0 |

| 2015 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga | 1 | 0 |

| 2016 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 2017 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 2018 | Transformation | 0 | 0 | |

| 2019 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga ELN Disidencia FARC EPL | 4 | 1 |

| 2020 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga Los Rastrosjos Disidencias FARC | 3 | 0 |

| 2021 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga ELN | 2 | 0 |

| 2022 | Transformation | Urabeños/Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia/Águilas Negras/Clan Úsuga ELN Disidencia FARC | 3 | 0 |

| 2023 | Transformation | Disidencia FARC | 1 | 0 |

References

- Borja, M. La historiografía de la guerra en Colombia durante el siglo XIX. Análisis Político 2015, 28, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A. Historia de Colombia y Sus Oligarquías (1498–2017). Available online: https://bibliotecanacional.gov.co/es-co/proyectos-digitales/historia-de-colombia/libro/index.html (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Caguasango, D.E.U.; van der Linde Valencia, C.G. Historias Cantadas de La Guerra: Los Corridos Prohibidos Como Memoria Del Conflicto En El Guaviare. Co-Herencia 2021, 18, 231–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, G.; Borda, O.F.; Luna, E.U. La Violencia En Colombia: Estudio de Un Proceso Social; Ediciones Tercer Mundo: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, G.; Borda, O.F.; Luna, E.U. La Violencia En Colombia Estudio de Un Proceso Social Tomo II; Ediciones Tercer Mundo: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- López de La Roche, F. El Gobierno de Juan Manuel Santos 2010-2015: Cambios En El Régimen Comunicativo, Protesta Social y Proceso de Paz Con Las FARC. Análisis Político 2015, 28, 377–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Pérez, F.E. Tierra, Territorio y Dinámicas de Guerra: Reflexiones a Partir Del Caso Colombiano. In La actualidad de la Reforma Agraria en América Latina y el Caribe, 1st ed.; CLACSO: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Rueda, R. La Historia de Las Guerras; Debate: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M. Territorio y Desplazamiento. El Caso Altos Cazucá Munic. Soacha Bogotá DC Fund. Cult. Javer. Artes Gráficas. 2004. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Territorio-Desplazamiento-Municipio-Exploratorio-Ambientales/dp/9586836797 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Gutierrez Sanin, F. ¿Un Nuevo Ciclo de La Guerra En Colombia? Debate: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koessl, M. Paramilitarimos. In Violencia y habitus paramilitarismo en colombia; Siglo del Hombre Editores: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Loaiza, A.G. Negociaciones de paz en Colombia, 1982–2009. Un estado del arte. Estud. Políticos 2012, 40, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richani, N. Systems of Violence: The Political Economy of War and Peace in Colombia, 1st ed.; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richani, N. Systems of Violence: The Political Economy of War and Peace in Colombia, 2nd ed.; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Richani, N. Fragmented Hegemony and the Dismantling of the War System in Colombia. Stud. Confl. Terror. 2020, 43, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, R.C. Toward a Theory of Political Violence: The Case of Rural Colombia. West. Polit. Q. 1965, 18, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, D. Civil War and Uncivil Development: Economic Globalisation and Political Violence in Colombia and Beyond; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clerici, N.; Richardson, J.-E.; Escobedo, F.; Posada, J.; Linares, M.; Sanchez, A.; Vargas, J. Colombia: Dealing in Conservation. Science 2016, 354, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clerici, N.; Salazar, C.; Pardo-Díaz, C.; Jiggins, C.D.; Richardson, J.E.; Linares, M. Peace in Colombia Is a Critical Moment for Neotropical Connectivity and Conservation: Save the Northern Andes–Amazon Biodiversity Bridge. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerici, N.; Armenteras, D.; Kareiva, P.; Botero, R.; Ramírez-Delgado, J.P.; Forero-Medina, G.; Ochoa, J.; Pedraza, C.; Schneider, L.; Lora, C. Deforestation in Colombian Protected Areas Increased during Post-Conflict Periods. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, L.; Romero, D.; Vargas, J.F. The Environmental Impact of Civil Conflict: The Deforestation Effect of Paramilitary Expansion in Colombia; Documento CEDE; Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Economía, CEDE: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo-López, B.E.; Castro, A.J.; Feijoo-Martínez, A. Nature’s Contributions to People Shape Sense of Place in the Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia. Agriculture 2022, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negret, P.J.; Allan, J.; Braczkowski, A.; Maron, M.; Watson, J.E. Need for Conservation Planning in Postconflict Colombia. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 499–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, M.; Saavedra, S.; Vargas, J.F. End-of-Conflict Deforestation: Evidence from Colombia’s Peace Agreement. World Dev. 2020, 129, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas-Cubillos, M.; Sylvester, J.; Villarino, E.; Pérez-Marulanda, L.; Ganzenmüller, R.; Löhr, K.; Bonatti, M.; Castro-Nunez, A. Forest Cover Changes and Public Policy: A Literature Review for Post-Conflict Colombia. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, Z. Unending War?: The Colombian Conflict, 1946 to the Present Day. PhD Thesis, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Molano, A. Los Años Del Tropel: Crónicas de La Violencia; Fondo Editorial CEREC: Bogotá, Colombia, 1985; ISBN 958-9061-08-7. [Google Scholar]

- González González, F.E. Poder y Violencia En Colombia; CINEP: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience of Ecosystems: Local Surprise and Global Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social–Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin III, F.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C.; Abel, N.; Clark, W.C.; Olsson, P.; Smith, D.M.S.; Walker, B.; Young, O.R. Ecosystem Stewardship: Sustainability Strategies for a Rapidly Changing Planet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelling, M.; Manuel-Navarrete, D. From Resilience to Transformation: The Adaptive Cycle in Two Mexican Urban Centers. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Galaz, V.; Boonstra, W.J. Sustainability Transformations: A Resilience Perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.-L.; Tjornbo, O.; Enfors, E.; Knapp, C.; Hodbod, J.; Baggio, J.A.; Norström, A.; Olsson, P.; Biggs, D. Studying the Complexity of Change: Toward an Analytical Framework for Understanding Deliberate Social-Ecological Transformations. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, art54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel Suárez, A. Naturaleza y dinámica de la guerra en Colombia. Cárdenas Becerra 2004, 55, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dexter, K.; Visseren-Hamakers, I. Forests in the Time of Peace. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredor-Garcia, J.; López Vega, F. The Logic of “War on Deforestation”: A Military Response to Climate Change in the Colombian Amazon. Alternatives 2023, 49, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R. The Economic Resilience of Regions: Towards an Evolutionary Approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.; Allen, C.R.; Holling, C.S. Ecological Resilience, Biodiversity, and Scale. Ecosystems 1998, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S.; Gunderson, L.H. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.H. Adaptive Dancing: Interactions between Social Resilience and Ecological Crises. Navig. Soc.-Ecol. Syst. Build. Resil. Complex. Change 2003, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom, S.M.; Allen, C.R. The Adaptive Cycle: More than a Metaphor. Ecol. Complex. 2019, 39, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soane, I.D.; Scolozzi, R.; Gretter, A.; Hubacek, K. Exploring Panarchy in Alpine Grasslands: An Application of Adaptive Cycle Concepts to the Conservation of a Cultural Landscape. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, art18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.C. Havens in a Firestorm: Perspectives from Baghdad on Resilience to Sectarian Violence. Civ. Wars 2012, 14, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordos, A.; Hyslop, D. The Assessment of Multisystemic Resilience in Conflict-Affected Populations. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 431–466. [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick, C. Resilience Humanitarianism and Peacebuilding. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Popham, C.M.; McEwen, F.S.; Pluess, M. Psychological Resilience in Response to Adverse Experiences. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; p. 395. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Ou, Y. Toward a Multisystemic Resilience Framework for Migrant Youth. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- De Coning, C. Adaptive Peacebuilding. Int. Aff. 2018, 94, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, A.E. Resilience in Peacebuilding: Contesting Uncertainty, Ambiguity, and Complexity. Contemp. Secur. Policy 2018, 39, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, C.; Huber-Sannwald, E.; Reyes Hernández, H.; van’t Hooft, A.; Schoon, M. Socio-Ecological Dynamics of a Tropical Agricultural Region: Historical Analysis of System Change and Opportunities. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.; Pérez-Belmont, P.; Schewenius, M.; Lerner, A.M.; Mazari-Hiriart, M. Assessing the Historical Adaptive Cycles of an Urban Social-Ecological System and Its Potential Future Resilience: The Case of Xochimilco, Mexico City. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla Nacher, M.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Jones, M.; Kalantari, Z. Application of the Adaptive Cycle and Panarchy in La Marjaleria Social-Ecological System: Reflections for Operability. Land 2021, 10, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Moore, M.-L. Transformations, Agency and Positive Tipping Points: A Resilience-Based Approach. In Positive Tipping Points Towards Sustainability: Understanding the Conditions and Strategies for Fast Decarbonization in Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, P. Building Resilient Peace in Liberia. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Conference of the African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific, Dunedin, New Zealand, 25–26 November 2014. Dunedin, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, P. Nurturing Adaptive Peace: Resilience Thinking for Peacebuilders. In Proceedings of the Commons Amidst Complexity and Change, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 25–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Balanzó, R.; Rodríguez-Planas, N. Crisis and Reorganization in Urban Dynamics: The Barcelona, Spain, Case Study. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca Núñez, C. Masacres En Colombia, 1995-2002: ¿violencia Indiscriminada o Racional? Universidad de los Andes: Bogotá, Colombia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, A.F. La Sevicia En Las Masacres de La Guerra Colombiana. Análisis Político 2008, 21, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- ¡Basta ya! Colombia: Memorias de Guerra y Dignidad: Informe General, 1st ed.; Suárez, A.F., González, F., Urpimny, R., Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Eds.; Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013; ISBN 978-958-57608-4-4. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Memoria Histórica Preguntas Frecuentes. Obs. Mem. Confl. 2020. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/cultura/areas/archivos/mc/archivos/cdmh/servicios/preguntas-frecuentes.html (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Observatorio de Memoria y Conflicto Masacres. Tablero Detall. Masacres 2025. Available online: https://micrositios.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/observatorio/portal-de-datos/el-conflicto-en-cifras/masacres/ (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Rudas, L. Las bases de datos del Centro de Memoria: Disputas por contar el origen del conflicto armado. Rutas Confl. 2024.

- Truong, C.; Oudre, L.; Vayatis, N. Selective Review of Offline Change Point Detection Methods. Signal Process. 2020, 167, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, J.G.; Ramón, G.U. El Orden de La Guerra: Las FARC-EP, Entre La Organización y La Política; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- InSight Crime Perfil de Colombia. Available online: https://es.insightcrime.org/noticias-crimen-organizado-colombia/colombia/ (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Arenas, J. La Guerrilla Por Dentro. No Title 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Chernick, M.W. Introducción. Aprender Del Pasado: Breve Historia de Los Procesos de Paz En Colombia (1982–1996). Colomb. Int. 1996, 36, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.L.A.; Rivera, D.M.R. El Narcotráfico En Colombia. Pioneros y Capos. Hist. Espac. 2008, 4, 169–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archila, M. El frente nacional: Una historia de enemistad social. Anu. Colomb. Hist. Soc. Cult. 1997, 24, 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- Albán, Á. Reforma y Contrareforma Agraria en Colombia. Rev. Econ. Inst. 2011, 13, 30. [Google Scholar]

- León Palacios, P.C. La Ambivalente Relación Entre El M-19 y La Anapo. Anu. Colomb. Hist. Soc. Cult. 2012, 39, 239–259. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, M.; Calle, Y.L.T. El Partido Político Como Arma Ciudadana: La Apuesta Del M-19 y Del FMLN. Rev. Pares 2022, 2, 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Atehortúa Cruz, A.L.; Rojas Rivera, D.M. Debate El Narcotráfico En Colombia. Pioneros y Capos. Hist. Espac. 2011, 10, 169–207. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez Mejía, J.F. La Influencia de Pablo Escobar En La Ciudad de Medellín. B.S. Thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, M.R. Política y Narcotráfico En El Valle: Del Testaferrato al Paramilitarismo Político. Rev. Foro 2005, 55, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amorocho, H.A.; Serrano, A.G. Gotas Que Agrietan La Roca: Crónicas, Entrevistas y Diálogos Sobre Territorios y Acceso a La Justicia; Siglo del Hombre Editores: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- del Pilar Gaitán, M. La Elección Popular de Alcaldes: Un Desafío Para La Democracia. Análisis Político 1988, 3, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Villarraga Sarmiento, Á. Biblioteca de La Paz. Los Procesos de Paz En Colombia, 1982–2014 (Documento Resumen); Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM-Misión Colombia): Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lopera Osorio, N. Apropiación Privada de Recursos Naturales, Relaciones Desiguales de Poder y Conflicto Armado: Un Análisis Del Departamento de Arauca, Colombia, Universidad de Antioquia. 2020. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.udea.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/a3fc7f54-bcc1-4a10-9c75-e049f0e9d24b/content (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Pedraza, O.H. El Ejercicio de La Liberación Nacional: Ética y Recursos Naturales En El ELN. Rev. Controv. 2008, 190, 198–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cubides Cipagauta, F. Santa Fe Ralito: Avatares e Incongruencias de Un Conato de Negociación. Análisis Político 2005, 18, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Uprimny, R.; Sánchez, L.M.; Sánchez, N.C. Justicia Para La Paz: Crímenes Atroces, Derecho a La Justicia y Paz Negociada; De Justicia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia Agudelo, G.D.; Mejía Walker, C.A. Ley de Justicia y Paz, Un Balance de Su Primer Lustro. Perf. Coyunt. Econ. 2010, 15, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique-Hernández, J.; Prieto-Bustos, W.O. Localización Del Conflicto Armado: El Fenómeno Paramilitar y Las Masacres. 2021. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.oducal.com/Record/ir-10983-27463?sid=70185 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Department of Peace and Conflict Research UCDP—Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Available online: https://ucdp.uu.se/ (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Cortés, D.; Vargas, J.F.; Hincapié, L.; del Franco, M.R. The Democratic Security Policy, Police Presence and Conflict in Colombia. Desarro. Soc. 2012, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, J.D.R.; Restrepo, V.L.F. Dinámica Reciente de Reorganización Paramilitar En Colombia. Rev. Controv. 2007, 189, 64–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, J.R.; García, J.Z. Democratic Security Policy in Colombia: Approaches to an Enemy-Centric Counterinsurgency Model. Rev. Humanidades 2019, 36, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.M.A. El Contexto Del Proceso de Paz Con Las FARC. Analecta Política 2013, 4, 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, Y. Claves Del Rechazo Del Plebiscito Para La Paz En Colombia. Estud. Políticos 2018, 52, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelvas, E.P.; Collazos, A.V. Colombia ante la Paz Total de Gustavo Petro; Documentos de Trabajo; Fundación Carolina: Bogotá, Colombia, 2023; pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnizo, C.N. Los Obstáculos Para La «paz Total» En Colombia. Nueva Soc. 2023, 305, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón, E.M.R. La Disidencia de Las FARC y El Futuro de La Paz En Colombia. Análisis Carol. 2019, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo Gomez, R.M.; Gómez Urrea, G.E.; Restrepo Gómez, C.J. Análisis Sobre La Evolución y Expansión de Las Disidencias de Las FARC En El Departamento Del Chocó; Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia: Quibdó, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze-Kraft, M. Evolution of Estimated Coca Cultivation and Cocaine Production in South America (Bolivia, Colombia and Peru) and of the Actors, Modalities and Routes of Cocaine Trafficking to Europe; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction: Cali, Colombia, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stoelinga, N. Cultivation and Competition in Colombia: Disentangling the Effects of Coca Price Changes on Violence. J. Int. Dev. 2024, 36, 1007–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, F.A.P. Distribución de La Propiedad Rural En Colombia En El Siglo XXI. Rev. Econ. E Sociol. Rural 2022, 60, e242402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettberg, A.; Dupont Bernal, F. Peace Agreement Implementation (PAI): What Matters? A Review of the Literature. Colomb. Int. 2023, 113, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidball, K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Elmqvist, T. Traps! An Introduction to Expanding Thinking on Persistent Maladaptive States in Pursuit of Resilience. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornelles, A.Z.; Boyd, E.; Nunes, R.J.; Asquith, M.; Boonstra, W.J.; Delabre, I.; Denney, J.M.; Grimm, V.; Jentsch, A.; Nicholas, K.A.; et al. Towards a Bridging Concept for Undesirable Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. Glob. Sustain. 2020, 3, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, A.; McAlpine, C.; Possingham, H. Historical Patterns and Drivers of Landscape Change in Colombia Since 1500: A Regionalized Spatial Approach. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2008, 98, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urzedo, D.; Chatterjee, P. The Colonial Reproduction of Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: Violence Against Indigenous Peoples for Land Development. In The Genocide-Ecocide Nexus; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-003-25398-3. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.O. Huida a La Libertad; Siglo XXI: Mexico City, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A.V.; Millington, A.C. Coca and Colonists: Quantifying and Explaining Forest Clearance under Coca and Anti-Narcotics Policy Regimes. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, J.; Mora, L.; Cubides, F. Colonización, Coca y Guerrilla; Colección James Henderson; Alianza Editorial Colombiana: Bogotá, Colombia, 1986; ISBN 9159389. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel, J.O. La Biodiversidad de Colombia. Palimpsestvs 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente Ordenación y Manejo de Bosques. 2018. Available online: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/direccion-de-bosques-biodiversidad-y-servicios-ecosistemicos/ordenacion-y-manejo-de-bosques-2/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Castro-Nunez, A.; Mertz, O.; Sosa, C.C. Geographic Overlaps between Priority Areas for Forest Carbon-Storage Efforts and Those for Delivering Peacebuilding Programs: Implications for Policy Design. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 054014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Ayram, C.A.; Etter, A.; Díaz-Timoté, J.; Rodríguez Buriticá, S.; Ramírez, W.; Corzo, G. Spatiotemporal Evaluation of the Human Footprint in Colombia: Four Decades of Anthropic Impact in Highly Biodiverse Ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Sandoval, P.J.; Gjerdseth, E.; Correa-Ayram, C.; Wrathall, D.; Van Den Hoek, J.; Dávalos, L.M.; Kennedy, R. No Peace for the Forest: Rapid, Widespread Land Changes in the Andes-Amazon Region Following the Colombian Civil War. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 69, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cuervo, A.M.; Aide, T.M.; Clark, M.L.; Etter, A. Land Cover Change in Colombia: Surprising Forest Recovery Trends between 2001 and 2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive after Extremely Aversive Events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, X.; Velez, M.A.; Moros, L.; Rodriguez, L.A. Beyond Proximate and Distal Causes of Land-Use Change: Linking Individual Motivations to Deforestation in Rural Contexts. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, art4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Eder, R. Place Attachment of Local Residents with an Urban Forest and Protected Area in Vienna; Hämeenlinna, Finland, 2008; pp. 28–31. Available online: https://forschung.boku.ac.at/en/publications/58419 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W.; Stedman, R.C. Environmental Concern: Examining the Role of Place Meaning and Place Attachment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, E.; Williams, K.J. Connectedness to Nature, Place Attachment and Conservation Behaviour: Testing Connectedness Theory among Farmers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, N.; Stein, T.V.; Holland, S.M.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, J.; Petitte, S. The Role of Place Attachment in Recreation Experience and Outcome Preferences among Forest Bathers. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The Relations between Natural and Civic Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynveen, C.J.; Schneider, I.E.; Arnberger, A. The Context of Place: Issues Measuring Place Attachment across Urban Forest Contexts. J. For. 2018, 116, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Coning, C. From Peacebuilding to Sustaining Peace: Implications of Complexity for Resilience and Sustainability. Resilience 2016, 4, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adaptive Cycle Phase | Agency of Social Capital (Action and Behavior) | Social Structure (Discourse and Institutions) |

|---|---|---|

| Institutionalized (K) | Agency reinforces and is aligned to dominant social structures and institutions. Alternative behavior is marginalized or excluded. | Cohesive structure legitimates prevalent social behavior. Alternative discourses and associated institutions are marginalized or excluded. |

| Transition | Likelihood of transition to a new state is influenced by cultural norms determining the limits of risk and loss tolerance and denial, institutional resistance to change, and capacity to cope with risk and loss. | |

| Scattered (Ω) | Diffused and diverse, social capital and behavior can break away from normalized routines and positions. A space for alternatives to emerge or be formed. | Established institutions and discourse are seen to have failed in providing security or explaining risk. While these structures are still in place they are no longer reinforced by social agency, initiating a crisis in structural reproduction. |

| Transition | New constellations of values emerge and compete for discursive dominance. | |

| Mobilized (α) | Social capital hardens around discrete value positions and specific coalitions of interest emerge. | Contradictory and supportive discourses and institutions coexist in overlapping emergent regimes. |

| Transition | Historical and political contexts shape the speed of movement from a focus on the building of internal cohesion for diverse social groups and their associated institutions and discourses to mobilization and competition between competing values and behavior. | |

| Polarized (r) | Competition between alternative social groups is overt. New hierarchies or non-hierarchies arise. | Fewer, but more forcefully argued differences in |

| Transition | Negotiation or imposition of a new risk social contract. | |

| Actor | Years of Participation in Massacres | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bandolerismos | 1930–1960 | Bandoleros emerged under the patronage of political elites who engaged regional political leaders, or gamonales, to enforce their political, ideological, and economic interests. Over time, these regional leaders evolved into political bandits, eventually degenerating into criminal banditry by the late 1960s. However, this form of banditry had an antithesis: social banditry, which was also created and led by actors with a liberal orientation [62]. |

| Guerrilla Groups | ||

| Communist Guerilla | 1964 | Colombian guerrilla groups emerged in the 1960s in response to unresolved agrarian issues and a history of addressing conflicts through violence. Their formation also stemmed from shortcomings of the National Front’s efforts to end bipartisan violence and was influenced by the rise in insurgent movements during the Cold War, inspired by the Cuban Revolution. In the database, for this year, the perpetrator of some massacres was listed as “Communist Guerrilla,” likely reflecting an inability to identify the specific group responsible [62]. |

| Popular Militias | 1992 | They were identified in the massacre database, but there is no historical record of them. |

| Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia -FARC- | 1965–2016 | Official FARC narratives link their emergence to military attacks on “independent republics” (1964–1966). Other accounts attribute their origins to the assassination of Jacobo Prías Alape (Charro Negro) by liberal guerrillas and their response to military operations reclaiming territory, which also impacted liberal guerrillas and conservative bands. The Marquetalia attack (May 1964), framed as State aggression against rural communities, marked their transition into a guerrilla organization [62,67]. |

| Ejército de Liberación Nacinal -ELN- | 1962–currently | Around the founding of the FARC (1965), the ELN (1962) and EPL (1967) emerged. These groups united radicalized urban youth inspired by the Cuban and Chinese revolutions with former gaitanista guerrillas from rural areas, all opposing the political restrictions of the National Front. The Cuban Revolution and the rise in youth as political actors globally fueled this movement [62]. |

| EPL | 1967–1991 | |

| EPL Dissidences | 1992–2000 | Other guerrilla groups have emerged as dissidents from the FARC, ELN, EPL, and M-19, some during the armed conflict and others following the demobilization of these organizations. Examples from the first category include the Socialist Renewal Current (Corriente de Renovación Socialista) and the Guevarist Revolutionary Army (Ejército Revolucionario Guevarista) as ELN dissidents, as well as the Ricardo Franco Front, a dissident faction of the FARC. In the second category are the EPL dissidents who rejected the 1991 peace accords and the Jaime Bateman Cayón Movement, formed as an M-19 dissident group after its demobilization in 1990 [62]. |

| FARC Dissidences | 1992 | |

| ELN Dissidences | 1992–1997 | |

| Quintin Lame Coordinadora | 1985–1990 | The Quintín Lame Armed Movement, an Indigenous self-defense group from northern Cauca, emerged in the 1980s, inspired by the historical figure Quintín Lame, a leader of the early 20th-century Indigenous movement. Comprising 80 Indigenous members, the group took up arms against the State, which had abandoned and stigmatized them, local landowners who used mercenaries to suppress their land reclamation efforts, and guerrilla groups attempting to force their recruitment. Despite their intentions to protect their communities, the movement ultimately became entangled in external conflicts, leaving their territory vulnerable and drawing their people into the very war they sought to avoid [62]. |

| Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera Simón Bolívar | 1987–1990 | The Simón Bolívar Guerrilla Coordinating Body, which unified all guerrilla groups at the time [62]. |

| Paramilitary groups | ||

| Muerte a Secuestradores -MAS- | 1981–1989 | At the start of the 1980s (December 1981), leaflets dropped from an airplane over Cali’s Pascual Guerrero Stadium announced the creation of Death to Kidnappers (MAS). This organization was established by a coalition of drug traffickers in response to the M-19 guerrilla group’s kidnapping of Martha Nieves Ochoa, sister of Jorge Luis, Juan David, and Fabio Ochoa, prominent members of the Medellín Cartel [62]. |

| Autodefensas Campesinas del Magdalena Medio | 1985–2005 | In the late 1980s, tensions between the national government and the military escalated, coinciding with the rapid transformation of self-defense groups into paramilitary forces. These groups unleashed brutal violence against civilians through massacres and targeted killings. During this period, paramilitary groups consolidated in Magdalena Medio and expanded to other regions: Córdoba under Fidel Castaño, Cesar led by the Prada brothers, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta under Hernán Giraldo and the Rojas family, Casanare under the Buitrago family, and the eastern plains and Putumayo with armed groups serving drug trafficking interests [62]. |

| Autodefensas de Hernán Giraldo | 1986–2000 | |

| Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (Buitragueños) | 1989–2003 | |

| Bloque Central Bolivar | 1991–2005 | |

| Los Tangueros | 1988–1991 | |

| Autodefensas Campesinas del Sur del Cesar | 1991–1998 | |

| Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia -AUC- | 1996–2006 | One key reason for the resurgence of paramilitarism in Colombia was the government’s re-establishment of a legal framework for self-defense groups through the Private Surveillance and Security Cooperatives (Decree 356 of 1994), known as “Convivir.” These cooperatives were approved under lenient criteria, allowing groups with questionable human rights records or ties to drug trafficking to operate. Additionally, paramilitarism experienced internal reorganization, which helped overcome stagnation from the early 1990s caused by internal disputes and efforts against Pablo Escobar. This restructuring led to a nationwide consolidation of paramilitary forces. In 1995, the Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá (ACCU) were formed, and in 1997, leaders from nine different paramilitary groups convened to establish the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), a unified political-military organization with a shared command structure, aimed at anti-subversive actions under the banner of self-defense [62]. |

| Autodefensas Campesinas del Vichada | 1997–1998 | |

| Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá -ACCU- | 1994–2000 | |

| Bloque Metro | 2001 | In retaliation for the FARC’s offensive in the Nudo del Paramillo, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) broke the agreed-upon Christmas truce and launched a campaign of massacres, targeted assassinations, and forced displacements nationwide, particularly affecting regions such as Bajo Putumayo and the departments of Bolívar, Sucre, Magdalena, and Antioquia. This violence included the Playón de Orozco massacre in El Piñón, Magdalena, in January 1999. At the beginning of this period, the AUC’s paramilitary structure consisted of five combat blocs, thirteen affiliated organizations, and a mobile training school. The Western Bloc of the AUC operated in southwestern Colombia, covering Córdoba, Antioquia, Chocó, Caldas, and Risaralda. The Northern Bloc coordinated the Caribbean coast fronts, while the Llanero Bloc oversaw fronts in Ariari, Guaviare, and the piedmont plains. The Metro Bloc managed fronts across southeastern, western, eastern, and northeastern Antioquia, all under the AUC General Staff based in the Nudo del Paramillo, in Córdoba [62]. |

| Unidentified Paramilitary Group | Paramilitary actions were not always carried out by organized illegal armed groups. In many instances, these actions were clandestinely conducted by radical sectors within the Armed Forces or through contract killings driven by opportunistic and functional alliances among various economic, political, and military actors. These collaborations did not necessarily aim to establish permanent groups or command structures [62]. | |

| Organized Crime | 1994 | Organized crime in Colombia grew rapidly in the 1970s, driven by the rising demand for cocaine in the United States. Criminal groups acted as intermediaries for shipments from Peru and Bolivia to North America [68]. In the analyzed database, organized crime is reported only for this year, indicating the lack of precise identification or specific affiliation of the group responsible for the reported massacre. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira-Sotelo, M.F.; Bousquet, F.; Piketty, M.G.; Castillo-Brieva, D. Using the Adaptive Cycle to Revisit the War–Peace Trajectory in Colombia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188422

Pereira-Sotelo MF, Bousquet F, Piketty MG, Castillo-Brieva D. Using the Adaptive Cycle to Revisit the War–Peace Trajectory in Colombia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188422

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira-Sotelo, Maria Fernanda, François Bousquet, Marie Gabrielle Piketty, and Daniel Castillo-Brieva. 2025. "Using the Adaptive Cycle to Revisit the War–Peace Trajectory in Colombia" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188422

APA StylePereira-Sotelo, M. F., Bousquet, F., Piketty, M. G., & Castillo-Brieva, D. (2025). Using the Adaptive Cycle to Revisit the War–Peace Trajectory in Colombia. Sustainability, 17(18), 8422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188422