Effects of the Supervision Down to the Countryside on Public Spending: Empirical Evidence from Rural China

Abstract

1. Introduction

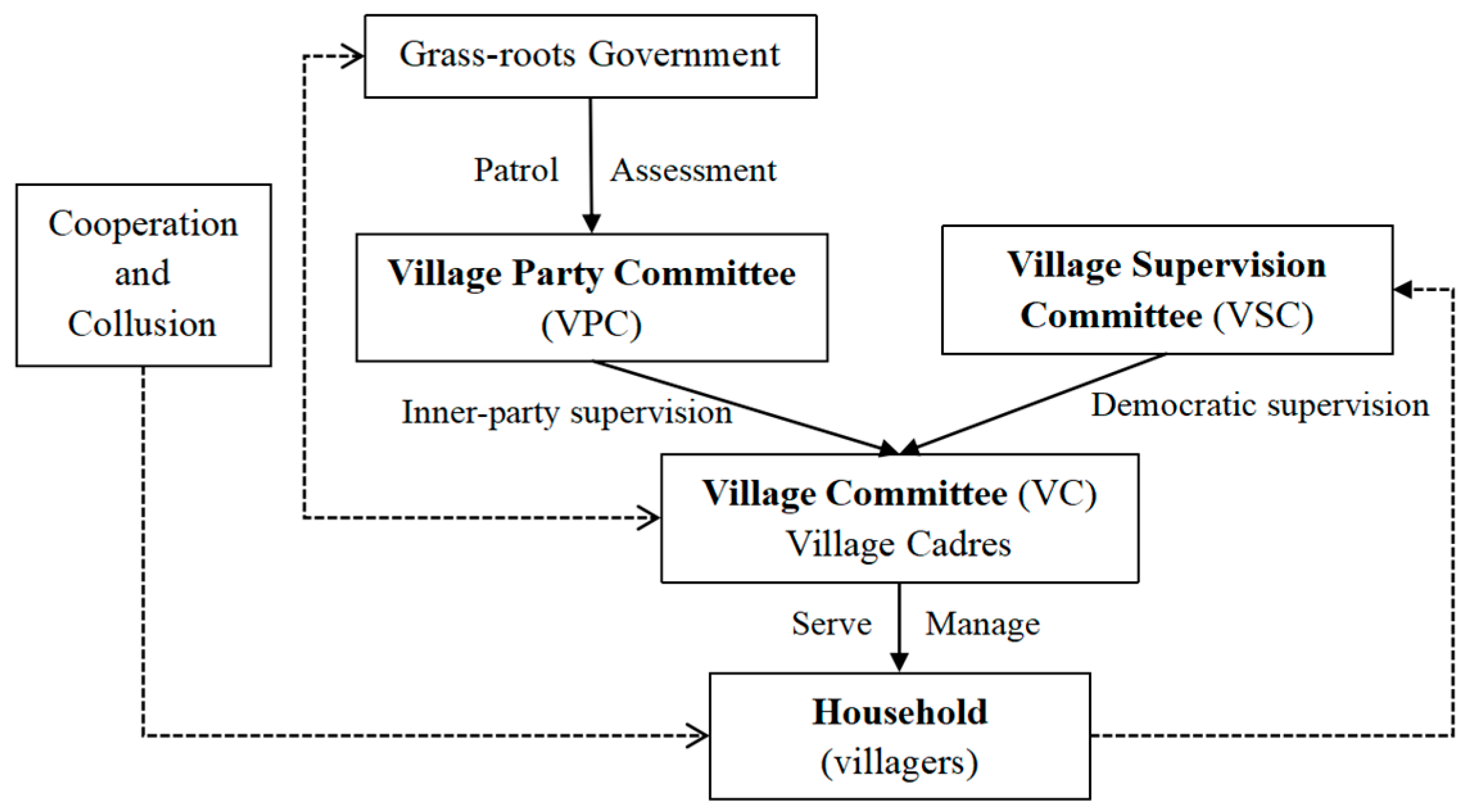

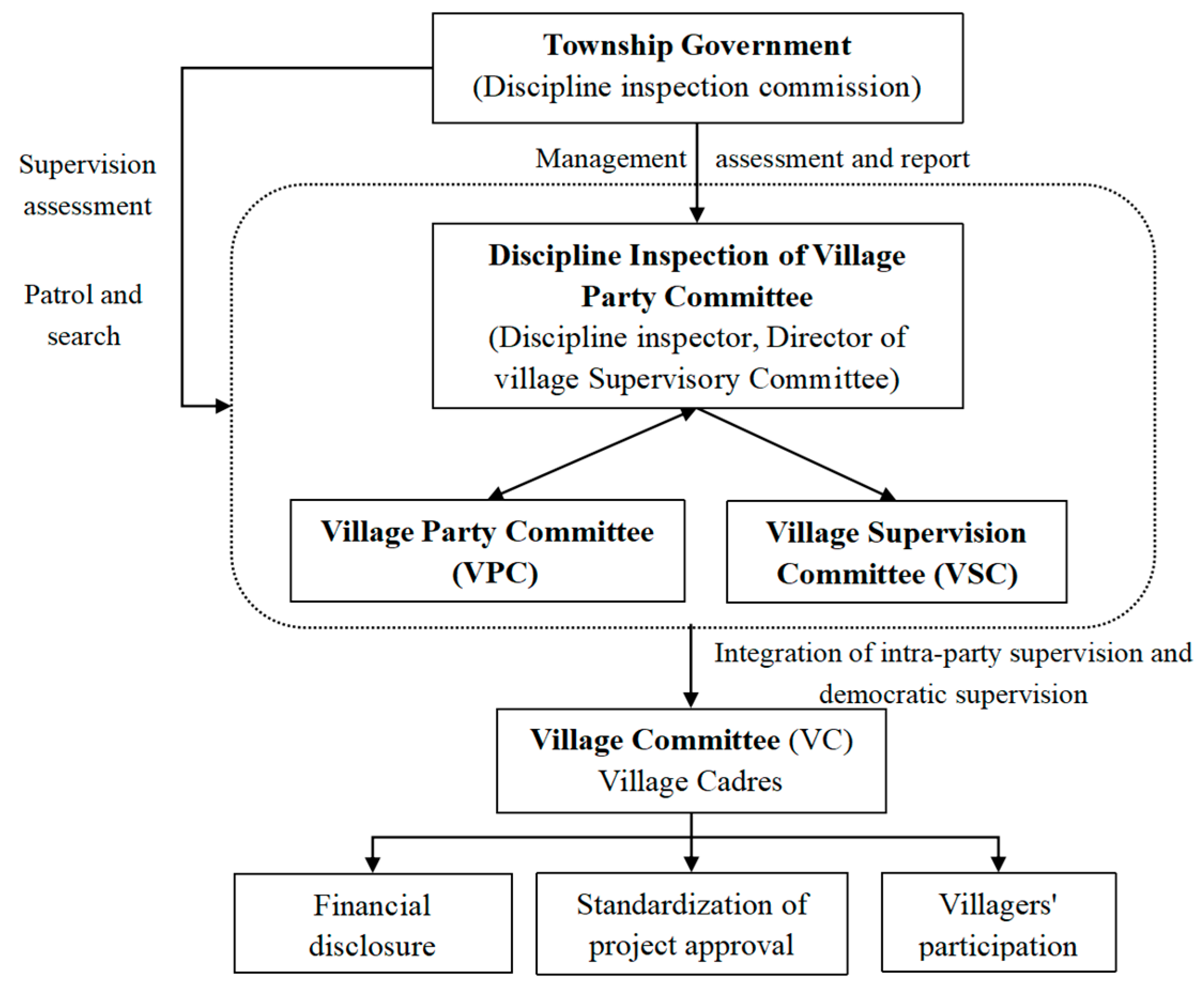

2. Policy Background and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Rural Supervision in China

2.2. Literature Review

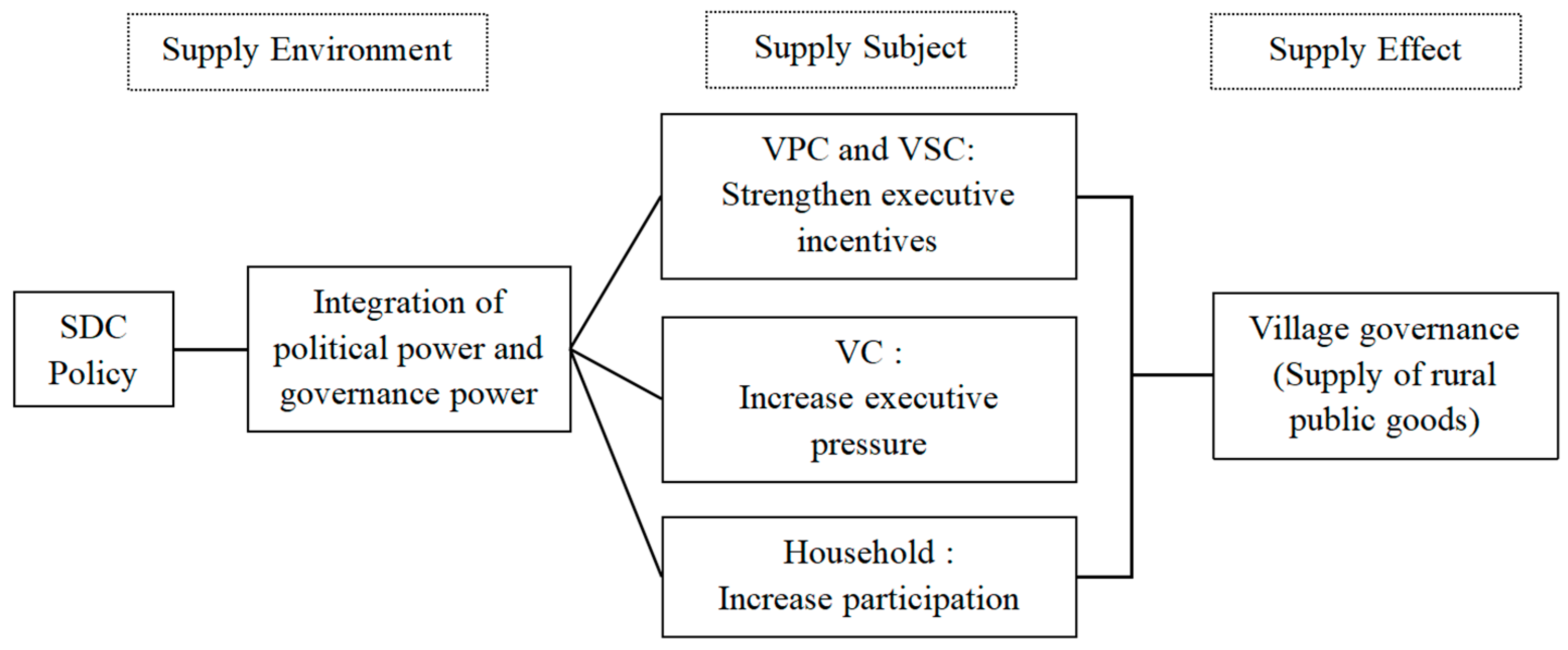

2.3. Theoretical Analysis

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Definition of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Mechanism Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Methods and Model Specification

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

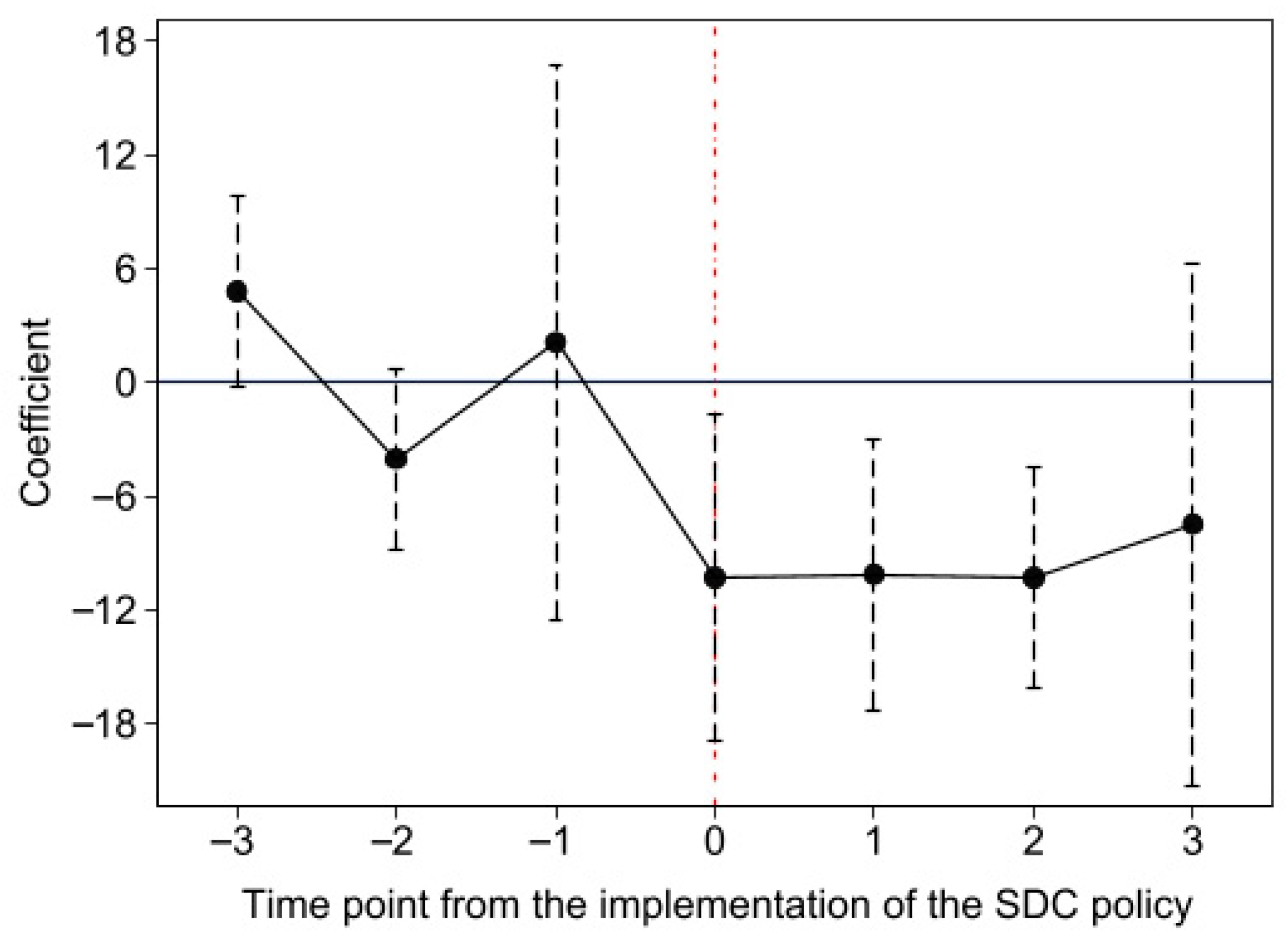

4.2. Parallel-Trend Test

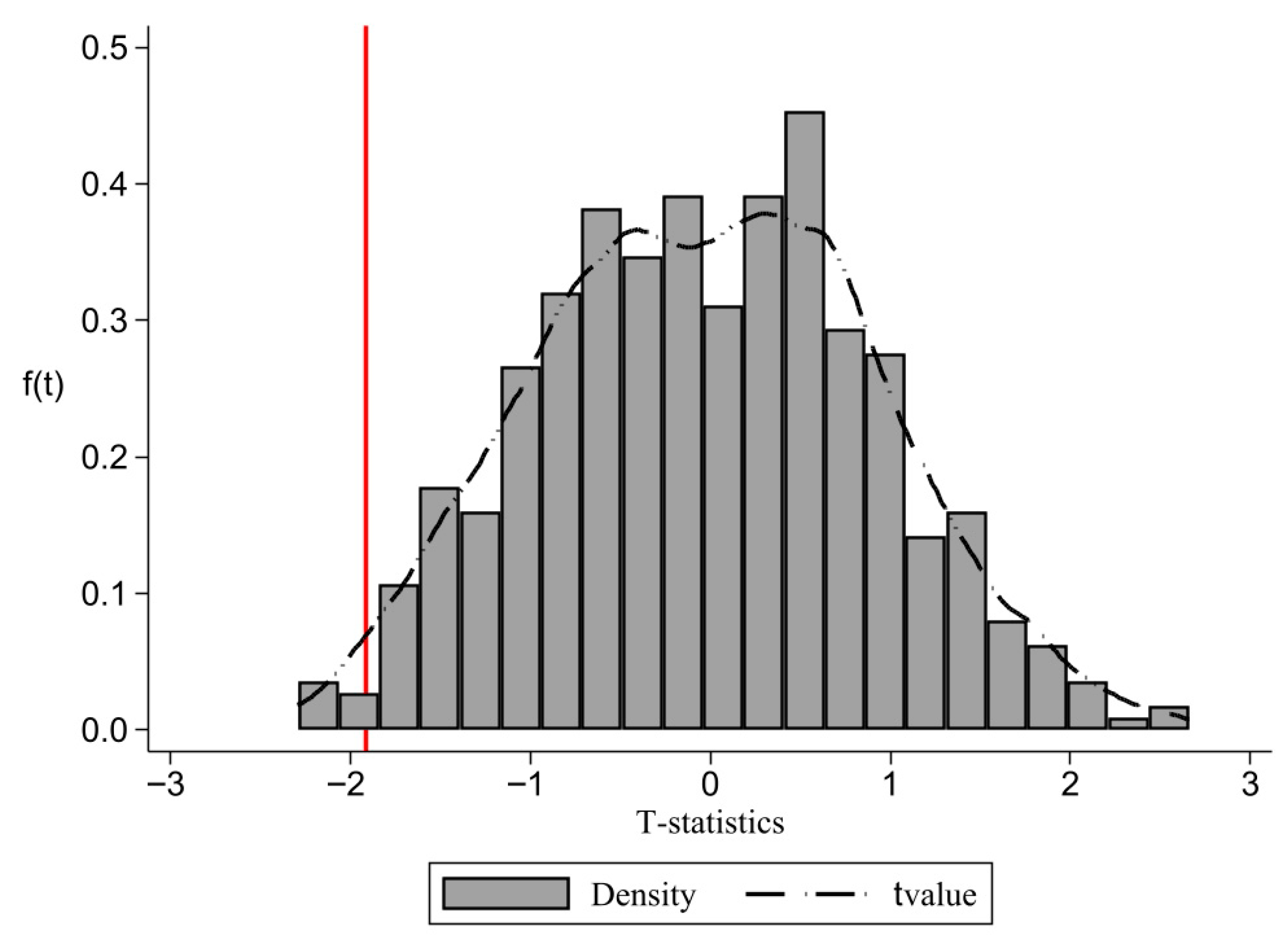

4.3. Placebo Test

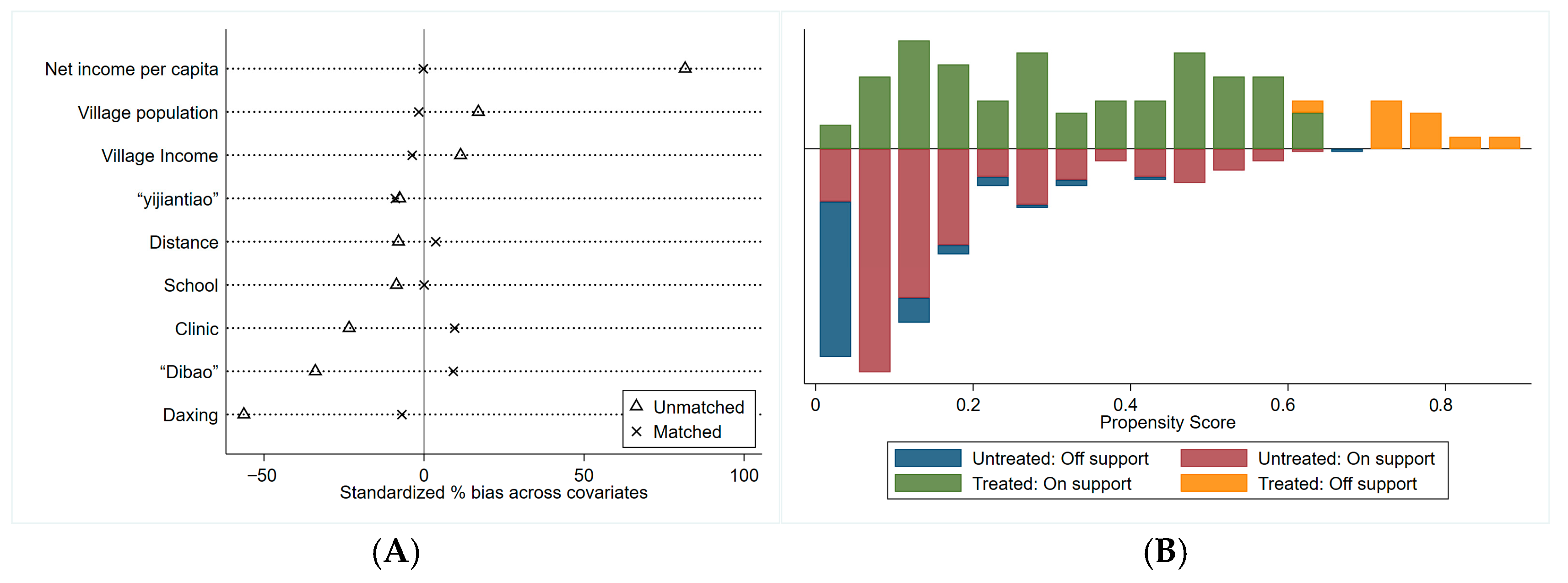

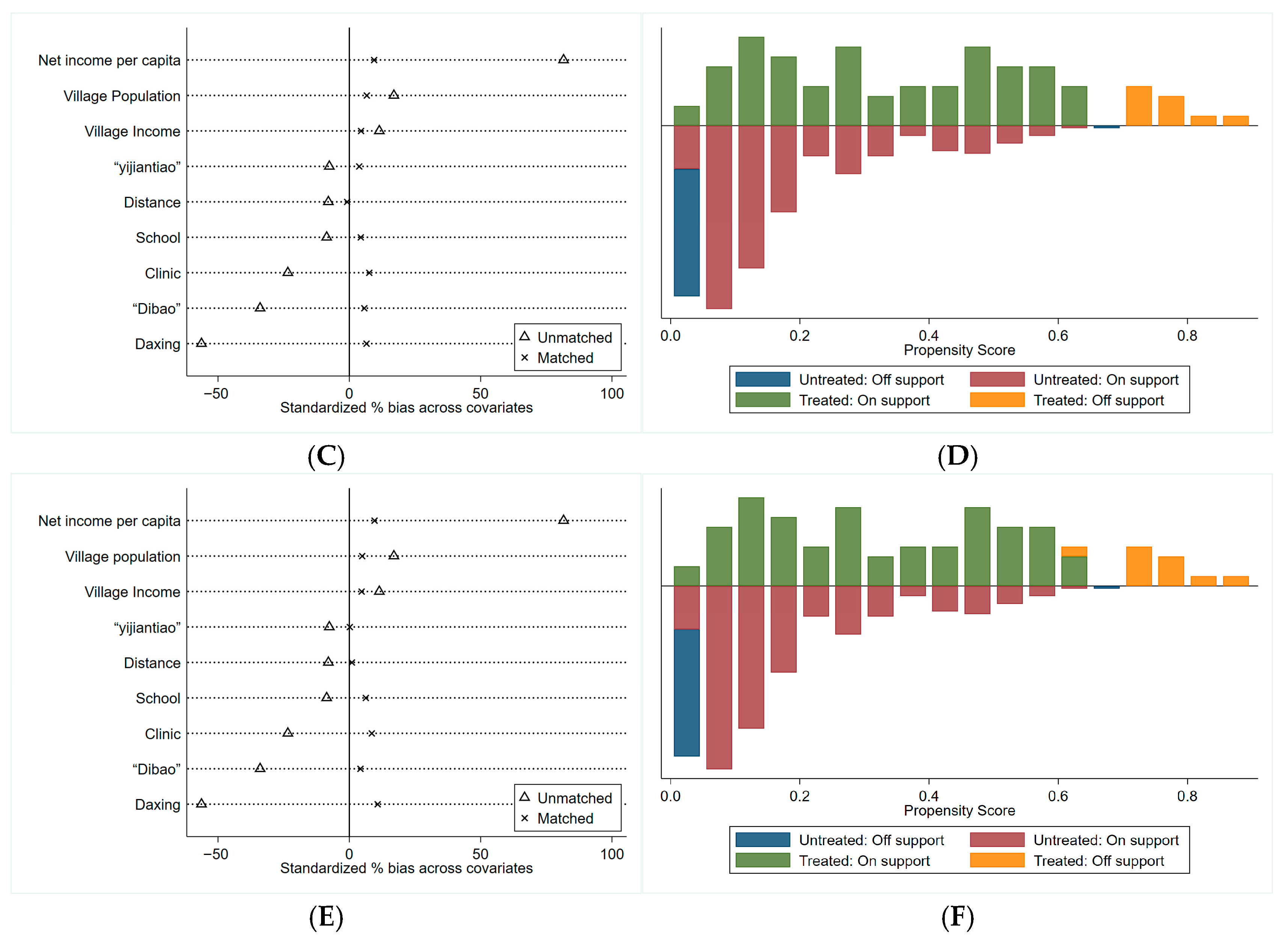

4.4. Robustness Test

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

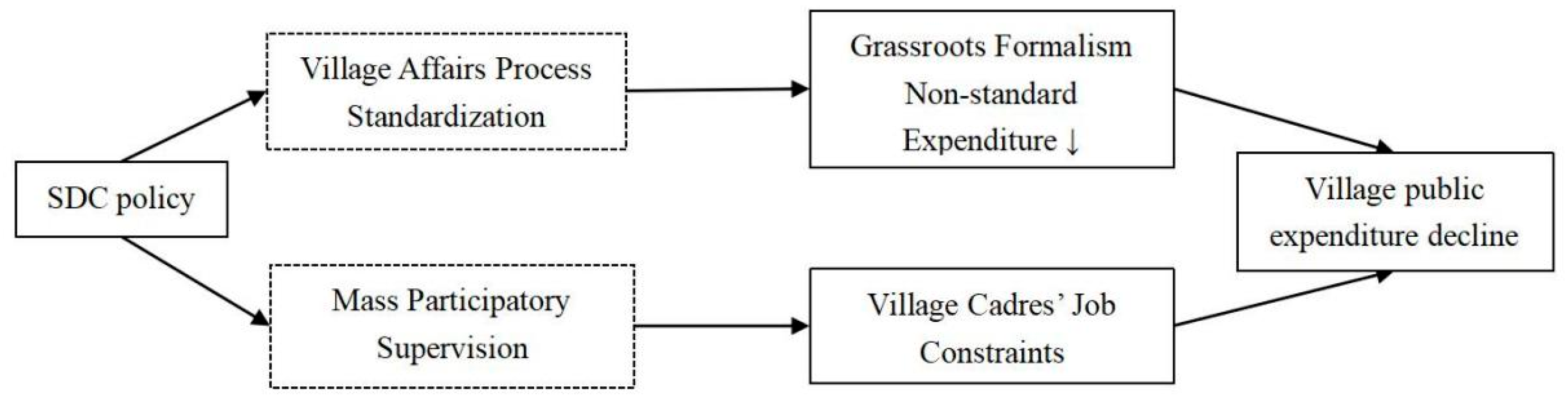

5. Mechanism Analysis

5.1. Regression Analysis: Budget Constraint Mechanism

5.2. Case Analysis: Further Discussion on the Implementation of Constraint Mechanisms

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

6.3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDC | Supervision down to the countryside |

| Exp | Total expenditure of the village |

| NIE | New investment in economic infrastructure of the village |

| NPE | New investment in social-security projects |

| NIS | Number of people benefited by economic infrastructure |

| NPS | Number of people benefited by social-security projects |

References

- Xu, Q.; Liu, J.; Xiong, C. Dynamic Evolution of Development Level, Regional Differences and Distribution of Rural Infrastructure in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2022, 39, 103–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. An Interpretation of the Current Suspension of Chinese Rural Public Cultural Services——From the Perspective of Historical Institutionalism. Libr. Trib. 2018, 38, 29–35. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/44.1306.G2.20170928.0830.008 (accessed on 28 September 2017). (In Chinese).

- Feng, J.; Gong, J.; Tian, X. Measurement and Evaluation of the Equity of China’s Rural Infrastructure Investment. Macroeconomics 2019, 2, 143–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Project System and “Last Mile” Problem of Rural Public Goods Supply. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 4, 62–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H. Analysis of Project-Based and Rural Public Goods Supply System-Taking Farmland Consolidation as an Example. CASS J. Political Sci. 2014, 4, 50–62. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=POLI201404005&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=uFRLdJzi/e1l6riYno7LadfAOCGbOCD1mZ2oNlCvVN+NhJUKuE9qISqzj0WlXjk+YHqvCXtrRGHx81IrcTALumak3t2KfYI1foy5o9nS67KH7bdiZzSdpNk6w3e1Gecti3okItIWjoLBUZReMlnxGpRHLReWj4whqs1DDO3HlKM= (accessed on 20 January 2015). (In Chinese).

- Chen, F. The Hierarchy of Profit Division and Grassroots Governance Involution: The Logic of Rural Governance under the Background of the Resource Input. Chin. J. Sociol. 2015, 35, 95–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Analysis of the Involution of National Resource Input: On the “Administrative Absorption of Self-governance” in the Use of Village Public Service Funds in Chengdu City. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 20, 34–40+46. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=BGYS202001004&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=ig4BMUJwSC8hci5vRO82W/2V3pFw9zq+3mvdWR0TCwBl1kRP1p1e5zTbJ1zc+Um8FuPgU0mYSGdEF7wiI9TZdxblzChISEfy9fIQxGIhNAr5KPewmjrBpZ675Qw/FewOpjI1qBOt7eJWmZzv4+q122Am86W/PBCYnwmxPjcIKjE= (accessed on 17 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Desai, R.; Anders, O. Can the poor organize? Public goods and self-help groups in rural India. World Dev. 2019, 121, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zuo, T. The role of the village committee in providing social security public goods. Issues Agric. Econ. 2011, 32, 60–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Pan, Z. Empowering village communities, activating self-governance, and effective supply of rural public goods. Rural Econ. 2022, 3, 22–31. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=NCJJ202203004&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=BLTtzl72ZDum+d5R9e3h+JFICHjTFXvnxa9deT1Dy+8Hw96/0ZXVF08ivu5Zfs7c7lhVgpeVaMoh/rqoPZ5Z/TEPHQm1Wk1yX7QVAkIEOMqBGdmeApmxX+IbxL/PeDnxOsPmZSBJx+Z66My+V9fpQIBk+97ArO8aYuMy4hVF/Ys= (accessed on 29 April 2022). (In Chinese).

- He, X. Supervision to the Countryside: A Study on the Modernization of Rural Governance in China, 1st ed.; Jiangxi Education Press: Nanchang, China, 2021; pp. 22–31+242–244. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J. Project-based: A new national governance system. Soc. Sci. China 2012, 5, 113–130+207. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=SHEK201204003&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=oI81rdmLjb+EokiLJKHFUcAUajrxTs196zm/DJMyFzfCFD6q10U/3s9DRhGVO/ClSErJcYl0WCrbqzxTfEtiR6JZmYSLO1M0GRwqFl+cadY/qm0/9z/maDlqArP75EwpCDa8gGu/HcAgLLUkanvFwwSwYnfekYTOPQQf83hyLvA= (accessed on 13 March 2013). (In Chinese).

- Li, Z. Grassroots Deconstruction of the Project System and Extended Study: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Agriculture-related Projects in A County. Open Times 2015, 2, 123–142+6. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=KFSD201502005&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=SbTSdc7VIIa+X3x9kVAGRyoUqlSmrfjX6bKQeg2sifXaWELsi+Ax8jLsmk6uxArd3TFpr73pfVMVIO3xiqdGGCRmquyIWjzVLj/NwCL9Mid5+7Wg1Izdd6YYKz82dFEzTxYqSVFdT+A2wHpHIjdwAgw+9OwIAR3Qjl9/rwKC5zU= (accessed on 9 September 2015). (In Chinese).

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Target Management Responsibility System: The Practical Logic of Local Party-State in Rural China. Sociol. Stud. 2009, 24, 61–92+244. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opinions on Strengthening the Standardized Management of Discipline Inspection Committee Members of Party Branches (General Branches) (Trial). Available online: http://www.dafeng.gov.cn/art/2015/5/4/art_24999_3572003.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Public Notice on the Website of the People’s Government of Shehong City. Available online: https://www.shehong.gov.cn/xinwen/show/a2b7065e143544af8e6566917532bc16.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Meng, X.; Zhang, L. Democratic participation, fiscal reform and local governance: Empirical evidence on Chinese villages. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gan, L.; Xu, L.C.; Yao, Y. Health shocks, village elections, and household income: Evidence from rural China-ScienceDirect. China Econ. Rev. 2014, 30, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrbek, A.; Serena, C.; Binayak, D.; Ahasan, H.M.; Lovisa, R.; Anna, T. Transparency, governance, and water and sanitation: Experimental evidence from schools in rural Bangladesh. J. Dev. Econ. 2023, 163, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X. Social Embeddedness, Power Balance, and Local Governance in China. World Dev. 2024, 179, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Zhang, D.; Choy, B.T.B.; Luo, B. The interaction between informal and formal institutions: A case study of private land property rights in rural China. Econ. Anal. Policy. 2021, 72, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, W. The politics of local government performance: Elite cohesion and cross-village constraints in decentralized Senegal. World Dev. 2018, 103, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Xu, W.; Cha, J. Rural entrepreneurship and job creation: The hybrid identity of village-cadre-entrepreneurs. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 70, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B.; Gretchen, W.; Symphorien, O. Global China and the ‘commons’: Rosewood governance in rural Ghana. World Dev. Sustain. 2024, 4, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, J.; Glenn Daniel, W. Participatory Democracy and Effective Policy: Is There a Link? Evidence from Rural Peru. World Dev. 2015, 66, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Han, R. Path to democracy? Assessing village elections in China. J. Contemp. China 2009, 18, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Bernstein, T. The impact of elections on the village structure of power: The relations between the village committees and the party branches. J. Contemp. China 2004, 13, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi, J.; Rozelle, S. Elections and power: The locus of decision-making in Chinese villages. China Q. 2000, 162, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Sun, X. Institutional bindingness, power structure, and land expropriation in China. World Dev. 2018, 109, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Warner, T.; Yang, D.; Liu, M. Patterns of Authority and Governance in Rural China: Who’s in charge? Why? J. Contemp. China 2013, 22, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. The Dual Marginalization: A Typologic Analysis of the Part Played by and the Behavior of Village Officials. J. Manag. World 2002, 11, 78–85+155–156. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The New Governance: Governing Without Government. Political Stud. 1996, 4, 652–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zheng, X. Supervision down to the Countryside and the Dilemma of Grassroots Governance. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 60, 10–18. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=HZSD202102003&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=k1VFB/tUiMM6eD3VsnpKJRhLOgV2I+eBneJVv96iW71fsPWC6Si4C2PPyuOF4aYWIq1TVkC3Yycw4VlmtAgMScEdjGiPyYimMWIjq7nNBxKy5g36V97ZArN/VBEhi7x2iMrSRxoutS+5prQBYQCebHHYEbDSW6YPXvXcDT3macg= (accessed on 25 March 2021). (In Chinese).

- Xu, C.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y. Does Village Affairs Supervision Committee Improve Rural Governance Performance: An Empirical Analysis Based on “Thousand Villages Survey” Data. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2023, 11, 164–184. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. A Study on the Systematic Optimization of Village-level Power Supervision Mechanism: Based on the Research Path of Theoretical Basis, Policy Basis and Practical Analysis. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 54, 147–159. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=ZJDX202407013&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=Hohs91+Y4D4v8mBNFiHP123QkSSOU6hfhL3iNDc9dZ4syPrE+je5oXQEL6ysxXKb2PqVwt688IDo61eO2Dr+noiAngrxbzA3lt2Izoyej5+ofQpHkqHv/YlV0AMzhSpASzvpFqIGXGqVFgCXOqobKv7XfLsiEipvSviNG1FOkiM= (accessed on 16 August 2024). (In Chinese).

- Dahyeon, J.; Ajay, S.; Laura, V.Z. De Jure versus De Facto transparency: Corruption in local public office in India. J. Public Econ. 2023, 221, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christa, B.; Päivi, L.; Primi, P.; Sabrina, S.; Indah, W. When petroleum revenue transparency policy meets citizen engagement reality: Survey evidence from Indonesia. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 230, 108529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophie, B.; Dustin, G.; Constance, L.M. Trust, hope, and collective action in fragile political settings: A qualitative comparative analysis of water user groups in Tunisia. World Dev. 2025, 189, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, P.L. Government transparency: Monitoring public policy accumulation and administrative overload. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Wang, R. From Credit Claiming to Blame Avoidance: The Change of Government Officials’ Behavior. CASS J. Political Sci. 2017, 2, 42–51+126. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=POLI201702004&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=GoWSItX3jefCCMCWDl0kLG1dtLUdzuCYuDR7ByewF2M46e5LIh3sWaskqfPqkS4oPpcDbeaFC/ulbZaQYhYyWZho81JR3yr0UwlkET8DZ8XnSqokh7YVkeVeW4I25mDXv8sNT1LdpPulzS1bRXoWXAHSXoSpsu7028zYz2Bto5k= (accessed on 11 July 2017). (In Chinese).

- Xu, J.; Yang, Y. On Delivery Efficiencies of Local Basic Public Services and Its Influencing Factors:Based on DEA Two-Stage Approach Corrected by Bootstrap. Financ. Trade Res. 2011, 22, 89–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Rural public goods supply and the reform of county and township fiscal and taxation systems. Issues Agric. Econ. 2011, 32, 54–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tan, Y. Public Expenditure Structure of Collective Economy and Villagers’ Happiness. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 21, 47–56. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=HNNA202204005&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=EVxb3LMoo+N/dZvLJdefjeNvgq/C99ECE2rJoIYuX4s/iB4yQS7xgPXlSdefsElVRmQcROEacmBUb3nrKMn3n1yoo2dbVBOQPUCBMU2z32SJY3HuqJMaHlveq8lUdx5Z/SQ/SjykzUAuLpUm/SnP0+bLRkYvt13Jw5imCZMmiu4= (accessed on 19 July 2025). (In Chinese).

- Li, Y. Rural Public Goods Supply-Side Structural Reform: Model Selection and Performance Enhancement—An Empirical Analysis Based on a Survey of 93 Sample Villages in 5 Provinces. J. Manag. World 2016, 11, 81–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H. Study on Standardization Systems for Equalization of Basic Public Services and Assessment Method of Fiscal Transfer Payment in China. Econ. Res. J. 2012, 47, 20–32+45. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=JJYJ201206003&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=bfRlRn9tdDHXF6jdewj5TYq1MvsDb1n84sR+CjkBAbIbOWFOxsmU6j+0KMZANze6D90iIi3ZYP3ZZzco0o1bqaMN8rbigdfyvFSOrSouwHhh0zrZavKo7wGbV0H0q2t5H7ra8OQ+O7FMKZc5bY1YvlelmZwJ8FwLdpsBDD/JbQQ= (accessed on 20 December 2012). (In Chinese).

- Holmström, B. Moral Hazard and Observability. Bell J. Econ. 1979, 10, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Christensen, T. Corruption and Accountability in China’s Rural Poverty Governance: Main Features from Village and Township Cadres. Int. J. Public Adm. 2021, 44, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S.H. Power and Wealth in Rural China: The Political Economy of Institutional Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, C.J. The Bite of Administrative Burden: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.; Herd, P.; Harvey, H. Administrative Burden: Learning, Psychological, and Compliance Costs in Citizen-State Interactions. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang-Trettien, C.; Bolger, D. Racialized Administrative Burden in Disability Assistance Programs in Two Rural Counties. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2024, 98, 446–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Ye, C.; Bai, Y. Does Supervision Down to the Countryside Level Benefit Rural Public Goods Supply? Evidence on the Extent of Households’ Satisfaction with Public Goods from 2005 to 2019. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán Uriel, J.; Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. Urban Horizons in China: Challenges and Opportunities for Community Intervention in a Country Marked by the Heihe-Tengchong Line. In Diversity as Catalyst: Economic Growth and Urban Resilience in Global Cityscapes. Urban Sustainability; Siew, G., Allam, Z., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Qiu, T.; Liu, D. Curbing Elite Capture or Enhancing Resources: Recentralizing Local Environmental Enforcement in China. China Q. 2025, 261, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Code | Obs | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Village public service expenditure | publicexp1 | 488 | 7.404 | 26.794 |

| Independent variable | ||||

| Supervision down to the countryside | DID | 495 | 0.162 | 0.368 |

| Natural geographical conditions | ||||

| Plowland area | plowland | 490 | 2722.673 | 2728.128 |

| Log (plowland area) | lnplowland | 490 | 7.353 | 1.404 |

| Distance between the village committee and the township government | distance | 499 | 5.786 | 6.859 |

| Socioeconomic attributes | ||||

| Villagers per capita net income | fincome | 494 | 6594.478 | 5623.962 |

| Log (villagers per capita net income) | lnfincome | 494 | 8.463 | 0.849 |

| the number of enterprises | enterprise | 490 | 3.943 | 9.363 |

| “Yijiantiao” (whether the Party secretary and the village branch secretary are the same or not) | election | 491 | 0.334 | 0.472 |

| Total population | population | 494 | 1587.221 | 1070.239 |

| Crackdown activities | crackdown | 375 | 0.387 | 0.488 |

| Number of reactionary organizations | reactionary | 375 | 1.851 | 3.540 |

| Villager disputes | villager disputes | 370 | 0.378 | 0.486 |

| Clan conflicts | clan conflicts | 365 | 0.186 | 0.390 |

| Village internal governance: characteristics of village cadres | ||||

| Belongs to the surname of the village or not | daxing | 493 | 0.416 | 0.493 |

| Education | edu | 493 | 3.560 | 0.816 |

| Working outside or not | outside | 493 | 0.183 | 0.387 |

| Working in a self-employed industry or not | business | 492 | 0.285 | 0.452 |

| Institutional arrangements | ||||

| Transfer payment | transincome | 495 | 10.161 | 31.609 |

| Village collective economic income | CEI | 486 | 30.215 | 82.959 |

| Log (village collective economic income) | lnCEI | 486 | 2.290 | 1.389 |

| Mechanism variable | ||||

| Total expenditure of the village | Exp | 496 | 26.196 | 68.064 |

| New investment in economic infrastructure | NIE | 474 | 39.124 | 83.953 |

| New investment in social-security projects | NIS | 488 | 215.214 | 220.239 |

| Number of people benefited by economic infrastructure | NPE | 496 | 31.5427 | 373.6279 |

| Number of people benefited by social-security projects | NPS | 483 | 72.504 | 180.730 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| DID | −5.857 ** | −6.712 * |

| (2.558) | (3.519) | |

| lnplowland | −2.117 | |

| (1.572) | ||

| distance | −0.253 *** | |

| (0.076) | ||

| lnfincome | −2.548 | |

| (2.297) | ||

| enterprise | −0.117 | |

| (0.086) | ||

| “yijiantiao” | 6.921 | |

| (4.656) | ||

| total population | 0.012 * | |

| (0.007) | ||

| daxing | 0.001 | |

| (2.006) | ||

| edu | 1.763 | |

| (2.156) | ||

| outside | −1.189 | |

| (1.969) | ||

| business | −2.588 | |

| (2.930) | ||

| transincome | 0.289 | |

| (0.268) | ||

| Constant | 1.549 | 13.880 |

| (1.294) | (18.800) | |

| Village fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.123 | 0.338 |

| Obs | 489 | 469 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DID | −11.584 * | −11.337 * | −14.733 * | −8.185 * |

| (6.384) | (6.305) | (7.537) | (4.562) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 469 | 469 | 450 | 469 |

| R2 | 0.388 | 0.389 | 0.394 | 0.378 |

| Variable | DID (Whether a Village Implemented SDC) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| crackdown | 0.00762 | |||

| (0.00919) | ||||

| reactionary | 0.00328 | |||

| (0.00387) | ||||

| villager disputes | 0.00680 | |||

| (0.00864) | ||||

| clan conflicts | −0.00239 | |||

| (0.0130) | ||||

| lnCEI | 0.0149 | 0.0150 | 0.0135 | 0.0151 |

| (0.0127) | (0.0127) | (0.0131) | (0.0133) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 344 | 344 | 339 | 334 |

| R2 | 0.7712 | 0.7713 | 0.7697 | 0.7709 |

| Sample | Pseudo R2 | LR chi2 | p > chi2 | MeanBias | MedBias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | 0.199 | 78.60 | 0.000 | 27.5 | 17.0 |

| Nearest neighbor matching (k = 2) | 0.011 | 2.07 | 0.990 | 4.9 | 3.7 |

| Kernel matching (bw = 0.03) | 0.004 | 0.83 | 1.000 | 5.5 | 5.7 |

| Radius matching (bw = 0.02) | 0.006 | 1.19 | 0.999 | 5.5 | 4.9 |

| Matching Method | ATT Effect | Std Error | T-Value | Controls | Treated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM (Nearest neighbor matching) | −11.9427 ** | 5.5479 | −2.15 | 366 | 71 |

| PSM (Kernel matching) | −11.4947 ** | 5.27498 | −2.18 | 384 | 72 |

| PSM (Radius matching) | −12.0210 ** | 5.3611 | −2.24 | 384 | 71 |

| Variable | Classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Development | Factional Conflicts | Evaluation of Village Cadres | ||||

| Weak | Stronger | Yes | No | Public Goods | Others | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| DID | 2.325 | −19.752 ** | 1.563 | −17.205 ** | 7.338 *** | −15.77 * |

| (4.170) | (9.286) | (5.733) | (8.371) | (2.101) | (8.903) | |

| Control Var. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 113 | 357 | 134 | 336 | 114 | 356 |

| R2 | 0.466 | 0.428 | 0.450 | 0.457 | 0.913 | 0.453 |

| Variable | Exp | NIE | NPE | NIS | NPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| DID | −34.930 * | −44.519 * | −59.646 | 73.272 | −64.994 * |

| (17.671) | (26.131) | (50.452) | (52.911) | (35.102) | |

| Control Var. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 477 | 0.279 | 0.310 | 0.141 | 0.175 |

| R2 | 0.497 | 457 | 469 | 477 | 464 |

| Mechanism | Measures | Tension Manifestation | Theoretical Lens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural formalization (institutional embeddedness) | -Reimbursement approval requires the signatures of five people -Small projects require villager assembly approval -Full financial disclosure | Autonomy erosion: -Administrative burden ↑ -Public service time ↑ | Rules penetrating local practice |

| Participatory oversight (participatory embeddedness) | -Supervisors include petitioners/village elites -Discipline committee director chairs oversight committee | Legitimacy trade-off: -Cadre accountability ↑ -Elite capture risk | State-engineered legitimacy building |

| Variables | Treat = 0 | Treat = 1 | Difference | T-Value | Data Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadres’ official conduct | |||||

| Collective asset liquidation | 0.9545 | 1.000 | 0.0454 | 1.6200 | 2019 |

| Households’ satisfaction with public services | |||||

| Roads | 0.5767 | 0.7117 | 0.1350 *** | 10.0130 | 2005, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2019 |

| Schools | 0.5502 | 0.5660 | 0.0158 | 0.3933 | 2005, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2019 |

| Clinics | 0.6248 | 0.6982 | 0.0734 *** | 5.4891 | 2005, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2019 |

| Drinking water | 0.7234 | 0.8532 | 0.1298 *** | 10.4001 | 2005, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2019 |

| Irrigation systems | 0.4731 | 0.6503 | 0.1772 *** | 12.6497 | 2005, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2019 |

| Drainage systems | 0.4853 | 0.6299 | 0.1442 *** | 9.8287 | 2005, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, S.; Ye, C.; Hu, W. Effects of the Supervision Down to the Countryside on Public Spending: Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188268

Zheng S, Ye C, Hu W. Effects of the Supervision Down to the Countryside on Public Spending: Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188268

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Suwen, Chunhui Ye, and Weibin Hu. 2025. "Effects of the Supervision Down to the Countryside on Public Spending: Empirical Evidence from Rural China" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188268

APA StyleZheng, S., Ye, C., & Hu, W. (2025). Effects of the Supervision Down to the Countryside on Public Spending: Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability, 17(18), 8268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188268