Job Satisfaction as a Factor That Moderates the Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Equation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Internal Social Responsibility

The responsible management of the impacts that are generated or could be generated by the operations of the enterprise over their employees, which implies minimizing the negative impacts and generating positive impacts that they are not forced to do so due to contracts or the law. These impacts occur or may occur in the context of day-to-day relations inside the company and involve all the human resource processes.

2.2. Definition of Organizational Commitment

2.3. Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment

2.3.1. Theories That Establish the Relationship Between ISR and OC

2.3.2. Empirical Evidence on the Relationship Between ISR and OC

| Article | Theories | Sample | ISR (CSR) Measurement | OC Measurement—Utilized Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [53] | Does not mention | Sample 1: marketing executives (n = 210) and students of MBA in the United States (n = 154) | Own scale | Indicators of other authors |

| [55] | Social identity | Business professionals of varied functional and organizational areas, in the USA (n = 278) | Maignan and Ferrell [53] | Indicators of other authors |

| [48] | Social identity | Retail banking employees of the United Kingdom (n = 4712) | Own scale | Indicators of other authors |

| [18] | Social identity | Business professionals from Turkey (n = 269) | Turker’s indicators [18] | Shortened OCQ |

| [58] | Does not mention | Employees of various companies in Pakistan (n = 371) | Turker’s indicators [18] | Shortened OCQ |

| [19] | Social exchange | Banking employees in Jordan (n = 336) | Own scale that measures give dimensions of ISR | Indicators from the TCM |

| [49] | Attribution | Employees and managers of two aluminum companies in China (n = 784) | Own indicators, taken from various authors | Indicators from the TCM |

| [64] | Does not mention | Employees of a German multinational that reside in 17 countries (n = 1084) | Own scale | Indicators from affective commitment, extracted from the OCQ and TCM |

| [52] | Social identity Organizational justice | Employees of five Chinese SMEs (n = 280) | Turker’s indicators [18] | Indicators from the TCM on Affective and Normative |

| [4] | Social exchange Social identity | Employees of 11 companies in Pakistan that disseminate CSR activities (n = 392) | Turker’s indicators [18] plus an indicator of Maignan and Ferrell [53] | Shortened version of the TCM |

| [40] | Social identity | Employees of enterprises with more than 300 employees in Belgium (n = 621) | Own scale, adapted from Maignan and Ferrell [53] | Revised version of the TCM |

| [51] | Social identity, Signaling Social exchange Organizational justice | Employees of 18 food enterprises in the USA (n = 827) | Own scale with eight indicators | Indicators from affective commitment from the TCM |

| [41] | Social identity Vision based on resources | Directors in Chinese enterprises (n = 175) | Own indicators on CSR (environment, ethic, philanthropy, relationship with stakeholders) | Five indicators of the TCM, that use the three types of commitment |

| [56] | Social identity Social exchange | Employees of enterprises located in three Chinese provinces (n = 700) | Scale based on Maignan and Ferrell [53] | Indicators from affective commitment from the TCM |

| [57] | Social identity | Teacher and employees of eight universities in Pakistan (n = 245) | Scale based on Maignan and Ferrell [53] | Shortened OCQ |

| [38] | Social identity Social exchange Deontic justice Social justice | Employees of 19 public and private enterprises, in Tunisia (n = 161) | Turker’s indicators [18] | Indicators from affective commitment from the TCM |

| [59] | Social identity Social exchange | Employees of five telecommunication enterprises in Pakistan (n = 229) | Turker’s indicators [18] | Indicators adapted from the TCM |

| [16] | Social identity | Employees of different hierarchical levels in Greece (n = 189) | Maignan and Ferrell scale [53] Differences between ISR from CSR | Indicators from affective and continuity commitment from the TCM |

| [61] | Social identity | Employees of six multinationals in Pakistan (n = 216) | Own scale inspired by Carroll [54] | Indicators of other authors |

| [62] | Does not mention | Workers in Ecuador (n = 318) | Own indicators, based on various previous works | Own indicators based on the OCQ, the TCM and others |

| [2] | Social identity Social exchange | Employees of manufacturing companies in Italy (n = 263) | Items on Turker’s scale [18] on ISR | Indicators from affective commitment from the TCM |

| [43] | Does not mention | Employees of universities in Indonesia (n = 254) | Own indicators on ISR and external CSR. | Indicators on affective, normative and continuity commitment. |

| [65] | Social exchange | Internal auditors of 15 banks in Jordan (n = 148) | Own scale | Three indicators from the TCM |

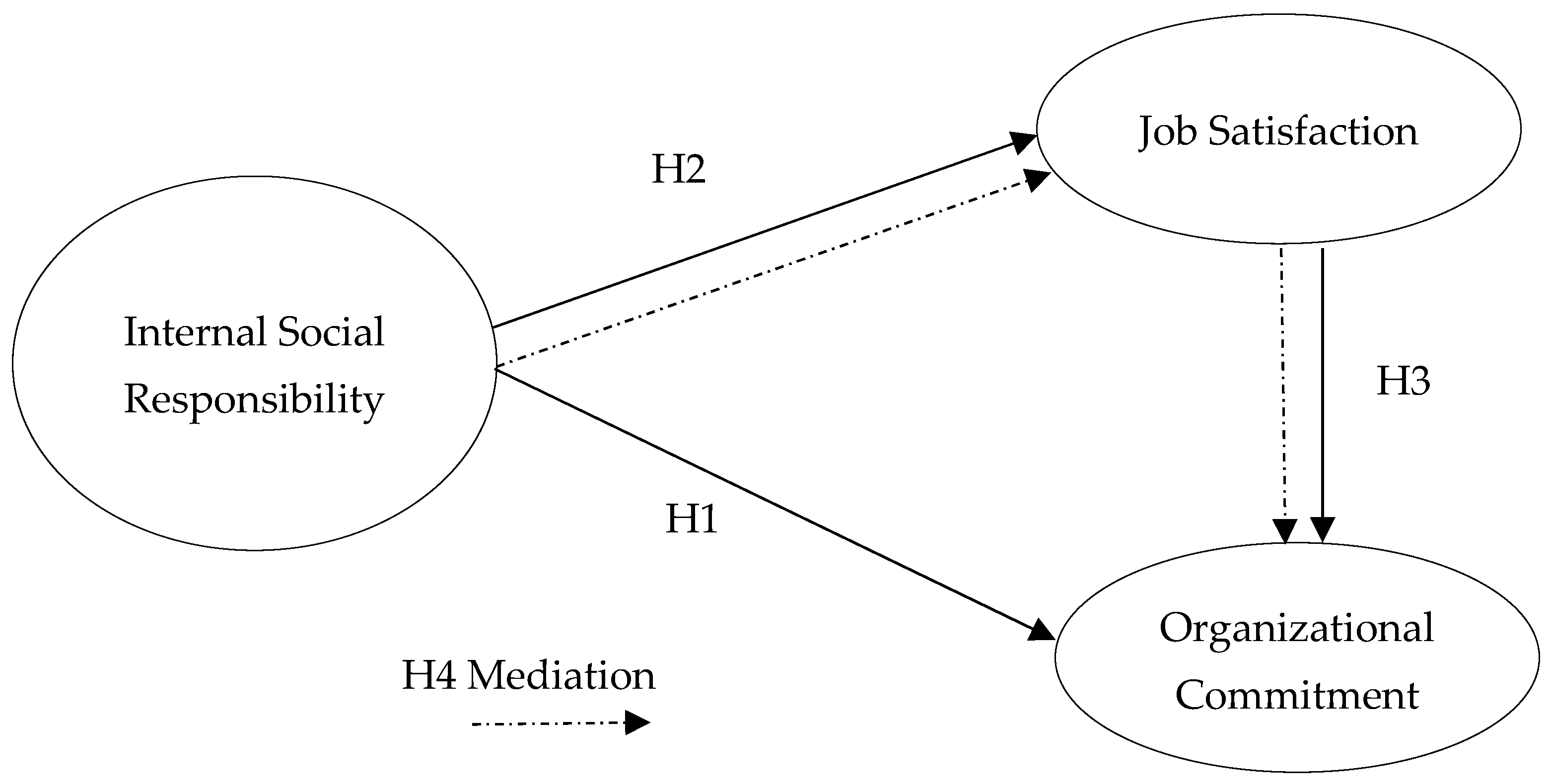

2.4. Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Internal Social Responsibility with Organizational Commitment

2.4.1. Definition of Job Satisfaction

2.4.2. Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Job Satisfaction

2.4.3. Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment

2.4.4. Job Satisfaction as a Mediator in the Relationship Between ISR and OC

3. Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Questionnaire and Variables

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Estimation of the Measurement Model

4.3. Modelling of Structural Equations and Testing of the Hypothesis

4.4. Correlations in Segments Determined by the Degree of Job Satisfaction

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications, Contribution to the Field of Study, and New Lines of Research

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yassin, Y.; Beckmann, M. CSR and employee outcomes: A systematic literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 75, 595–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.J.; Khalid, M.H. Linking corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment: The role of employee job satisfaction. J. Glob. Responsib. 2025, 16, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorito, J.; Bozeman, D.P.; Young, A.; Meurs, J.A. Organizational commitment, human resource practices, and organizational characteristics. J. Manag. Issues 2007, 19, 186–207. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Vallete, F. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment: Exploring Multiple Mediation Mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Anuario Estadístico Nacional 2022; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2023; Available online: https://www.gub.uy/instituto-nacional-estadistica/comunicacion/publicaciones/anuario-estadistico-nacional-2022 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Hayat, M.; Iqbal, A.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmad, Z. Students’ perception about corporate social responsibility: Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2022, 16, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A. Toward a Workable Definition of Social Corporate Responsibility: A Restitutive Approach. J. Altern. Perspect. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Licandro, O.; Vázquez-Burguete, J.L.; Ortigueira, L.; Correa, P. Definition of corporate social responsibility as a management philosophy oriented towards the management of externalities: Proposal and argumentation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F. Building a European Portrait of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, G. Achieving corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1976, 1, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26000:2010; Guidance on Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. Available online: https://iso26000.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ISO-26000_2010_E_OBPpages.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Johnson, H.L. Business in Contemporary Society: Framework and Issues; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ena, B.; Delgado, S. Recursos Humanos y Responsabilidad Social Corporativa; Ediciones Paraninfo: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Obeidat, B. Exploring the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility, Employee Engagement, and Organizational Performance: The Case of Jordanian Mobile Telecommunication Companies. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Syst. Sci. 2016, 9, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, E.C.; Manolopoulos, D.; Agapitou, V. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: Interrelations of external and internal orientations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, L.T.H.; Lang, L.D.; Ngo, T.L.P.; Ferreira, J. The impact of internal social responsibility on service employees’ job satisfaction and organizational engagement. Serv. Bus. 2024, 18, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-bdour, A.A.; Nasruddin, E.; Lin, S.K. The relationship between internal corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment within the banking sector in Jordan. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2010, 5, 932–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reder, A. In Pursuit of Principle and Profit: Business Success Through Social Responsibility; Putnam: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gaete, R. Discursos de gestión de recursos humanos presentes en Iniciativas y Normas de responsabilidad social. Rev. Gac. Labor. 2010, 16, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ofenhejm, A.; Queiroz, A. Sustainable human resource management and social and environmental responsibility: An agenda for debate. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2019, 59, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licandro, O. Job satisfaction and organizational climate as mediators in the relationship between internal social responsibility and organizational commitment. Estud. Adm. 2022, 29, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, O. La dimensión interna de la responsabilidad social en las micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas del programa expopyme de la Universidad del Norte. Pensam. Gestión 2011, 31, 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, M. Dimensión Interna de la Responsabilidad Social Empresaria desde la óptica de la Gestión de Recursos Humanos. Saber Univ. Oriente Venez. 2016, 28, 794–805. [Google Scholar]

- Albinger, H.S.; Freeman, S.J. Corporate social performance and attractiveness as employer to different job seeking population. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buciuniene, I.; Kazlauskaite, R. The linkage between HRM, CSR and performance outcomes. Balt. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Barcik, A.; Dziwiński, P. The effect of the internal side of social responsibility on firm competitive success in the business services industry. Sustainability 2016, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López, M.; Romero, P. The link between socially responsible human resource management and intellectual capital. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, T.; Bierema, L. Corporate social responsibility: Issues for human resource development professionals. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2008, 12, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Guía para la Elaboración de Memorias de Sostenibilidad; GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- SA8000:2008; Responsabilidad Social 8000. Social Accountability International: New York, NY, USA, 2008. Available online: https://share.google/5dfkss0BJfRNNDR5e (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Ethos. Indicadores ETHOS de Responsabilidade Social; Ethos: São Paulo, Brasil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji, C. Toward a New Measure of Organizational Commitment. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 1986, 21, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, D. Validating the dimensionality of Porter et al.’s measurement of organizational commitment in a non-Western culture setting. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M.E. Involvements as Mechanisms Producing Commitment to the Organization. Adm. Sci. Q. 1971, 16, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K.; Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M.; Russo, M. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment: A multiple mediation model. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B. Building Organizational Commitment: The Socialization of Managers in Work Organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1974, 19, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closon, C.; Leys, C.; Hellemans, C. Perceptions of corporate social responsibility, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Manag. Res. 2015, 13, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, Y.; Yu, Y. The Influence of Perceived Corporate Sustainability Practices on Employees and Organizational Performance. Sustainability 2014, 6, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Chávez, Y.; Jaramillo Villanueva, J.L.; Hernández Chávez, G. Relationship between organizational commitment and employee turnover. Estud. Adm. 2021, 28, 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.D.; Tanuwijaya, J.; Putra, A.W.G. The Effect Of Corporate Social Responsibility, Job Crafting, Employee Motivation, Employee Engagement And Job Satisfaction On Organizational Commitment. EKOMBIS Rev. J. Ekon. Bisnis 2025, 13, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commeiras, N.; Fournier, C. Critical evaluation of Porter et al.’s organizational commitment questionnaire: Implications for researchers. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2001, 21, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhu, C. Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3020–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas, A.; Kelly, K. The Effects of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Antecedents and benefits of corporate citizenship: An investigation of French businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 51, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.K. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Di Fan, D.; Zhu, C.J. High-Performance Work Systems, Corporate Social Performance and Employee Outcomes: Exploring the Missing Links. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrar-ul-Haq, M.; Kuchinke, K.P.; Iqbal, A. The relationship between corporate social responsibility, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment: Case of Pakistani higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2352–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Rehman, K.; Ali, S.I.; Yousaf, J.; Zia, M. Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, U.; Nadeem, R. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Affective Organizational Commitment: Role of CSR Strategic Importance and Organizational Identification. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 704–726. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagheer, O.; Umer, M.; Aslam, S. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Employees’ Performance (EP): A Mediating Role of Organization Commitment (OC) in the Multinationals Companies (MNCs) of Pakistan. NUML Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loor-Zambrano, H.Y.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Relationship CSR and employee commitment: Mediating effects of internal motivation and trust. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.L. Responsabilidad social y el compromiso organizacional de empleados públicos del Perú. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2021, 26, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shbail, M.O.; Alshurafat, H.; Ensour, W.; Al Amosh, H.; Al-Hazaima, H. Exploring the impact of internal CSR on auditor turnover intentions: The mediating and moderating roles of job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and job complexity. Acta Psychol. 2025, 256, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agho, A.O.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Discriminant validity of measures of job satisfaction, positive affectivity and negative affectivity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1992, 65, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrington, D. The effects of a central incentive-motivational state on measures of job satisfaction. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1973, 10, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr.; Ford, N.M.; Walker, O.C., Jr. Organizational climate and job satisfaction in the salesforce. J. Mark. Res. 1976, 13, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, M.D.; Sharda, R. A neural network model for bankruptcy prediction. In Proceedings of the 1990 IJCNN International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, San Diego, CA, USA, 17–21 June 1990; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currivan, D.B. The causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in models of employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1999, 9, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobet, J.; Fito, A. Contingent workforce, organizational commitment and job satisfaction: Review, discussion and research agenda. Omnia Sci. 2013, 9, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Eliyana, A.; Pradana, I.I. The Effect of Work-Family Conflict on Job Satisfaction with Organizational Commitment as the Moderator Variable. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1979, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, L.; Kervin, J.; Clark, K.; Reid, F.; Sirola, W. Explaining nursing turnover intent: Job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, or organizational commitment? J. Organ. Behav. 1998, 19, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.M.; Othman, B.J.; Gardi, B.; Ahmed, S.A.; Sabir, B.Y.; Ismael, N.B.; Hamza, P.A.; Sorguli, S.; Ali, B.J.; Anwar, G. Employee Commitment: The Relationship between Employee Commitment And Job Satisfaction. J. Humanit. Educ. Dev. 2021, 3, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, A.; Noor, M.A.; Safkaur, T.L.; Suprayitno, D.; Setiawan, A. Job Satisfaction as a Mediation of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Commitment and Employee Performance. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2025, 5, e03140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelwan, O.S.; Lengkong, V.P.K.; Tewal, B.; Pratiknj, M.H.; Saerang, R.T.; Ratag, S.P.; Kawet, R.C. The effect of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior on Turnover Intention in the tourism management and environmental sector in Minahasa Regency-North Sulawesi-Indonesia. Rev. Gest. Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e05242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.R.; Isabella, G.; Boaventura, J.M.G.; Mazzon, J.A. The influence of corporate social responsibility on employee satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhakim, A.S.; Agwa, Y.I. The effect of corporate social responsibility on job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention in fast-food restaurants in Egypt. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 5, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barpanda, S. Influence of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Engagement and Job Satisfaction. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 42, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Alonazi, W.B.; Malik, A.; Zainol, N.R. Does corporate social responsibility moderate the nexus of organizational culture and job satisfaction? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichers, A.E. Conflict and organizational commitments. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefny, L. The relationships between job satisfaction dimensions, organizational commitment and turnover intention: The moderating role of ethical climate in travel agencies. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.; Steers, R.; Porter, L. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A longitudinal analysis of the early development and consequences of organizational commitment. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 1987, 19, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Sánchez, D.; Recio Reyes, R.; Avalos Sekeres, M.; González Ortiz, J. Satisfacción Laboral y Compromiso en las organizaciones de Río Verde, S.L.P. Rev. Psicol. Cienc. Comport. 2013, 4, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mottaz, C. An Analysis of the Relationship Between Work Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. Sociol. Q. 2016, 28, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisque, R.; Paucar, S. Satisfacción laboral y compromiso organizacional de docentes en una universidad pública de Perú. Apunt. Univ. 2020, 10, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, D.; Hylton, R. Nurse migration: Job satisfaction and organizational commitment among nurses in the Caribbean. Indian J. Health Well-Being 2021, 12, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, D. Job satisfaction and organizational continuance commitment: A two-wave panel study. J. Organ. Behav. 1996, 17, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Strasser, S. A longitudinal analysis of the antecedents of organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. Examining the causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, S.; He, H.; Mellahi, K. Corporate Social Responsibility, Employee Organizational Identification, and Creative Effort: The Moderating Impact of Corporate Ability. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Chan, T.J.; Hasan, N.A.M. Mediating role of job satisfaction on internal corporate social responsibility practices and employee engagement in higher education sector. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2020, 16, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaad, M.; Amir, A.; Bashir, A.; Hasan, T. Human resource practices and organizational commitment: The mediating role of job satisfaction in emerging economy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1608668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambudiri, D.R.; Tewari, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: The Mediation of Job Satisfaction; ANZAM: Brisbane, Australia, 2010; Available online: https://www.anzam.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf-manager/802_ANZAM2010-297.PDF (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Ting, S.C. The effect of internal marketing on organizational commitment: Job involvement and job satisfaction as mediators. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licandro, O.; Burguete, J.L.V.; Ortigueira-Sánchez, L.C.; Correa, P. Corporate Social Responsibility and financial performance: A relationship mediated by stakeholder satisfaction. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Burguete, J.L.; Licandro, O.; Ortigueira-Sánchez, L.C.; Correa, P. Do Enterprises That Publish Sustainability Reports Have a Better Developed Environmental Responsibility and Are They More Transparent? Sustainability 2024, 16, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licandro, O.D. Análisis de la relación entre aplicación de la Responsabilidad Social y existencia de gerentes para liderarla. Rev. Int. Investig. Cienc. Soc. 2022, 18, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licandro, O.D.; Correa, P. Relación entre el género del director ejecutivo y la aplicación de la responsabilidad social empresarial. Estud. Gerenciales 2022, 38, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Schaller, T.K.; Patil, A. Common method variance in advertising research: When to be concerned and how to control for it. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Partial least squares path modeling. In Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Dimension | Code | Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Social Responsibility | Discrimination/diversity | ISR1 | Does everything possible so people do not feel discriminated by their age, gender, race, religion, handicap, etc. |

| Protection of human rights | ISR2 | Handles disciplinary measures respectfully | |

| Handling of information | ISR3 | Informs the employees on relevant matters that affect or could affect them (changes in tasks or place of work, etc.) | |

| Dialogue with employees | ISR4 | Listen to employees when they express dissatisfaction, raise concerns, or file a complaint | |

| Labor climate | ISR5 | Promotes a good work and relationship environment within the company | |

| Health and job security | ISR6 | Prevents accidents at work and cares for the security of employees | |

| ISR7 | Prevents work illnesses (stress, tendinitis, back issues, etc.) and brings support to the employees when they get them | ||

| Promote professional development | ISR8 | Promotes and facilitates employee training and professional development | |

| Promote personal development | ISR9 | Promotes the participation and initiative of their employees | |

| Social benefits for employees and their families | ISR10 | Provides support to employees facing personal or family problems (health, financial, addiction, etc.) | |

| Act in an ethical manner | ISR11 | Promotes that bosses act in an ethical manner and treat their subordinates in a just way | |

| Organizational Commitment | Identification | OC1 | I think that my values and those of this company are very similar |

| OC2 | I have pride in telling others I am part of this company/organization | ||

| OC3 | For me, this is the best company/enterprise possible to work at | ||

| Effort | OC4 | I am willing to make much more effort than what is normally expected of me, in order to help the success of this company/organization | |

| OC5 | This company/organization really brings out the best of me regarding my performance at work | ||

| OC6 | I would be willing to do almost any task in order to continue working in this company/organization | ||

| Membership | OC7 | I feel a lot of loyalty towards this company/organization | |

| OC8 | For me to quit this company/organization drastic changes in my current circumstances would have to occur (work or personal) | ||

| OC9 | Having chosen to work in this company/organization has been a good decision on my part | ||

| Job Satisfaction | Structural aspects | JS1 | I am satisfied with the work environment in this company |

| JS2 | I am satisfied with the conditions of my job | ||

| Function | JS3 | I am satisfied with the tasks I do | |

| JS4 | I am satisfied with the responsibilities I am given | ||

| Interpersonal relationships | JS5 | I am satisfied with the understanding I have with my peers | |

| JS6 | I am satisfied with the understanding I have with my direct superior |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Loading | t Student | p | Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Social Responsibility | 0.976 | 0.977 | 0.979 | 0.811 | |||||

| ISR1 | 3.413 | 1.613 | 0.799 | 29.266 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR2 | 3.060 | 1.626 | 0.907 | 43.521 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR3 | 3.181 | 1.580 | 0.917 | 50.385 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR4 | 3.198 | 1.621 | 0.903 | 45.823 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR5 | 3.232 | 1.635 | 0.901 | 47.714 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR6 | 2.838 | 1.573 | 0.918 | 49.070 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR7 | 2.936 | 1.591 | 0.925 | 53.497 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR8 | 3.033 | 1.611 | 0.937 | 51.854 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR9 | 3.136 | 1.581 | 0.874 | 45.019 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR10 | 3.024 | 1.592 | 0.933 | 47.860 | 0.000 | ||||

| ISR11 | 3.053 | 1.569 | 0.884 | 40.983 | 0.000 | ||||

| Job Satisfaction | 0.976 | 0.977 | 0.979 | 0.811 | |||||

| JS1 | 3.184 | 1.591 | 0.839 | 55.630 | 0.000 | ||||

| JS2 | 3.737 | 1.465 | 0.891 | 66.174 | 0.000 | ||||

| JS3 | 3.267 | 1.454 | 0.873 | 63.921 | 0.000 | ||||

| JS4 | 3.726 | 1.376 | 0.838 | 39.983 | 0.000 | ||||

| JS5 | 3.689 | 1.462 | 0.905 | 85.438 | 0.000 | ||||

| JS6 | 3.606 | 1.490 | 0.870 | 61.104 | 0.000 | ||||

| Organizational Commitment | 0.951 | 0.955 | 0.959 | 0.722 | |||||

| OC1 | 3.043 | 1.552 | 0.815 | 40.575 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC3 | 3.422 | 1.554 | 0.901 | 87.792 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC3 | 2.862 | 1.514 | 0.879 | 79.550 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC4 | 3.532 | 1.487 | 0.843 | 46.735 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC5 | 3.143 | 1.535 | 0.908 | 88.167 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC6 | 2.690 | 1.485 | 0.743 | 29.524 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC7 | 3.403 | 1.553 | 0.878 | 64.099 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC8 | 3.470 | 1.539 | 0.797 | 36.693 | 0.000 | ||||

| OC9 | 3.492 | 1.486 | 0.869 | 35.772 | 0.000 | ||||

| Internal Social Responsibility | Job Satisfaction | Organizational Commitment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Social Responsibility | 0.900 | 0.772 | 0.777 |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.743 | 0.870 | 0.858 |

| Organizational Commitment | 0.751 | 0.813 | 0.850 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | β | VIF | t-Student | p-Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Internal Social Responsibility → Job Satisfaction | 0.743 *** | 1.000 | 29.906 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | Internal Social Responsibility → Organizational Commitment | 0.328 *** | 2.230 | 6.538 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3 | Job Satisfaction → Organizational Commitment | 0.570 *** | 2.230 | 11.823 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4 | Internal Social Responsibility → Job Satisfaction → Organizational Commitment | 0.423 *** | 11.149 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Indexes | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Percentiles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33% | 67% | ||||

| ISR Index | 3.13 | 3.27 | 1.48647 | 1.91 | 4.36 |

| Job Satisfaction Index | 3.47 | 3.83 | 1.36374 | 2.67 | 4.50 |

| Organizational Commitment Index | 3.20 | 3.44 | 1.35390 | 2.44 | 4.11 |

| Job Satisfaction Level | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Low satisfaction (<2.67) | 0.504 ** |

| Average satisfaction (2.67 to 4.50) | 0.516 ** |

| High satisfaction (>4.50) | 0.389 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Licandro, O.; Severino-González, P.; Ortigueira-Sánchez, L.; Veas-González, I.; Correa, P.; Trigos-Tapia, P.; Rojas-Bravo, V.; Villanueva-Arequipeño, T.; Rebolledo-Aburto, G. Job Satisfaction as a Factor That Moderates the Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Equation Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188091

Licandro O, Severino-González P, Ortigueira-Sánchez L, Veas-González I, Correa P, Trigos-Tapia P, Rojas-Bravo V, Villanueva-Arequipeño T, Rebolledo-Aburto G. Job Satisfaction as a Factor That Moderates the Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Equation Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188091

Chicago/Turabian StyleLicandro, Oscar, Pedro Severino-González, Luis Ortigueira-Sánchez, Iván Veas-González, Patricia Correa, Pool Trigos-Tapia, Violeta Rojas-Bravo, Tomy Villanueva-Arequipeño, and Guipsy Rebolledo-Aburto. 2025. "Job Satisfaction as a Factor That Moderates the Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Equation Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188091

APA StyleLicandro, O., Severino-González, P., Ortigueira-Sánchez, L., Veas-González, I., Correa, P., Trigos-Tapia, P., Rojas-Bravo, V., Villanueva-Arequipeño, T., & Rebolledo-Aburto, G. (2025). Job Satisfaction as a Factor That Moderates the Relationship Between Internal Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Equation Analysis. Sustainability, 17(18), 8091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188091