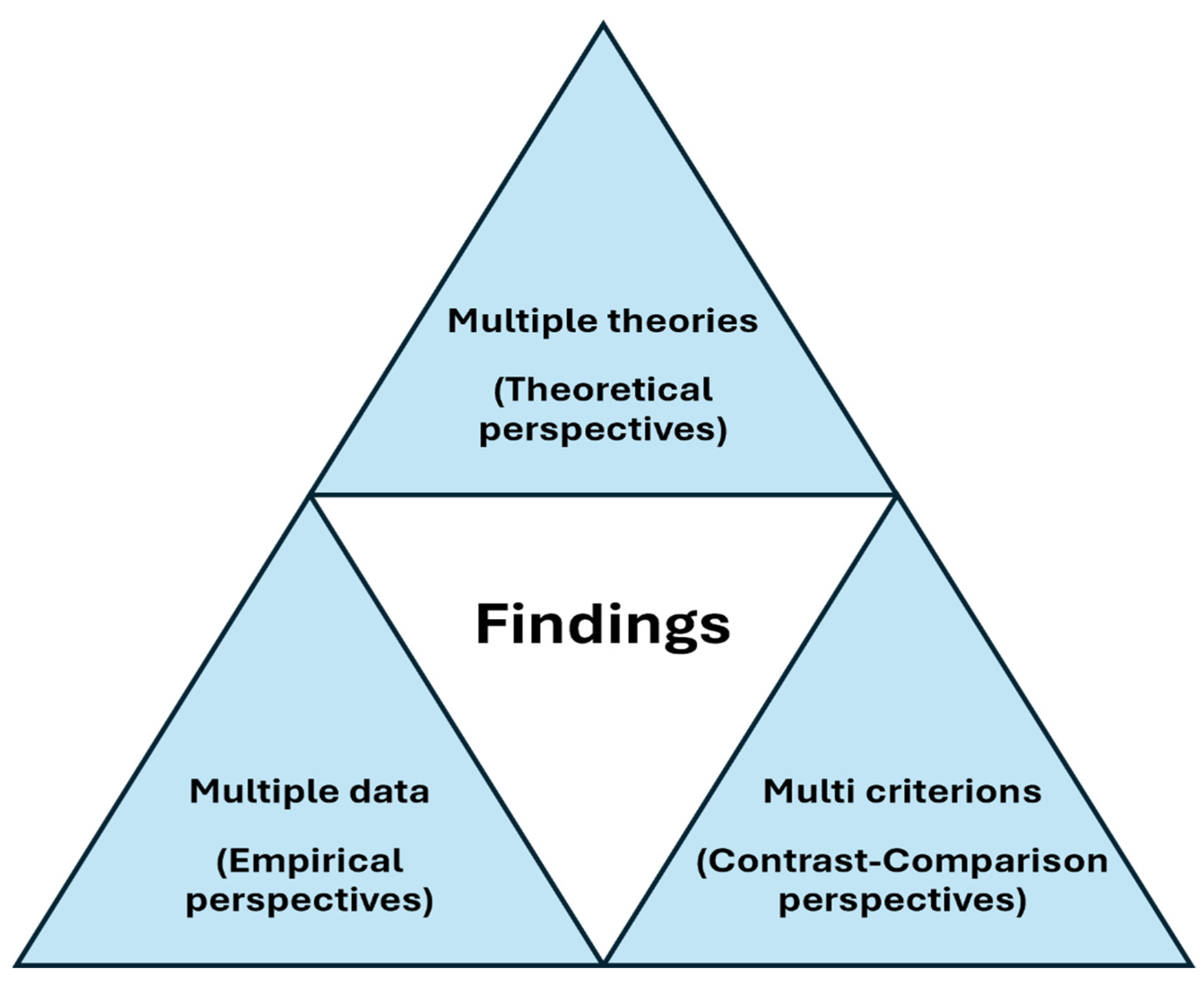

3.1. Existing Theories of Leadership

There is extensive literature on common leadership styles and how to choose the most effective one, whether it be transactional, transformational, bureaucratic, or laissez-faire. However, leadership involves much more than just giving orders or delegating tasks. It is a complex combination of skills, traits, and strategies that can greatly impact an organization’s sustainability, success, and the well-being of its members, particularly in times of change. Goleman has explored the intricacies of leadership in depth by identifying six distinct leadership styles, emphasizing that sustainability-embedded leadership involves recognizing that different situations may require different approaches [

14].

Visionary leaders contribute to sustainability by clearly articulating a future that is grounded in purpose and long-term benefit. Their strength lies in answering the essential question of direction: “Where are we going?” When the vision centers on sustainability goals such as aligning business strategies with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), these leaders can mobilize collective energy and focus. They provide a unifying narrative that connects day-to-day work with broader environmental and social outcomes. By making sustainability a core part of the organizational vision, they help individuals see their contributions as part of a greater mission outcome. This not only motivates action but also sustains engagement through periods of change, when clarity of purpose becomes most critical. For example, during transitions to green technologies or shifts in supply chain practices, visionary leaders can stabilize uncertainty by keeping the long-term sustainable outcome front and center. This ensures that sustainability is not treated as a side initiative but as the destination of the organization’s trajectory [

15].

Coaching leaders, on the other hand, invest deeply in people. Their impact on sustainability comes from fostering continuous learning and long-term skill development. By focusing on mentorship and personal growth, they prepare teams to be adaptable and resilient—qualities essential for sustainable innovation. In the context of sustainability, this might mean nurturing skills related to renewable energy, data-driven environmental analysis, or sustainable operations. These leaders take the time to understand the unique strengths and challenges of their team members, offering support that is personal and constructive. This tailored guidance not only enhances performance but also embeds sustainability in the culture by promoting growth mindsets. Over time, this creates a workforce that is better equipped to lead green initiatives, adapt to regulatory shifts, and think critically about ethical decision-making. The emphasis on development over quick wins makes coaching leadership particularly suited for sustainability, where long-term success often depends on building capabilities that do not produce immediate returns.

Affiliative leaders contribute by creating cohesive, emotionally intelligent teams that function well under pressure and uncertainty. Sustainability work is inherently collaborative and often involves navigating differing priorities, values, and perspectives. Affiliative leaders smooth this path by fostering trust, empathy, and mutual respect within teams. When morale dips or conflict arises, these leaders work to restore harmony, creating environments where people feel safe to speak, question, and challenge assumptions—key conditions for sustainability-driven innovation. A psychologically safe workplace is more likely to support employee-led green initiatives, admit when practices are falling short, and push for systemic changes that require group cohesion. By prioritizing relationship-building and emotional well-being, affiliative leaders ensure that sustainability is embedded not just in strategy but in everyday team dynamics. This strengthens the social fabric of organizations, which is essential for enduring sustainability initiatives that must outlast short-term pressures.

Democratic leadership is integral to sustainability due to its emphasis on participatory decision-making and the integration of diverse stakeholder perspectives. Democratic leaders foster a culture of inclusive dialogue, ensuring that employees at all levels have a voice in shaping sustainability strategies and actions. This leadership style not only enhances the quality and legitimacy of decisions by tapping the collective intelligence of the workforce, but also strengthens employee buy-in and accountability for sustainability outcomes. Democratic leaders encourage open forums, collaborative workshops, and feedback mechanisms that capture a broad spectrum of ideas, leading to innovative solutions for complex sustainability challenges [

13]. By valuing employee input, they imbue team members with a sense of ownership over both process and results, motivating proactive contributions to environmental stewardship, social equity, and sustainable economic growth.

Pacesetting leaders offer a different but still valuable contribution to sustainability by modeling excellence and setting ambitious standards. These leaders push their teams to achieve high performance, often by demonstrating what is possible through their own efforts. In sustainability-focused organizations, a pacesetting leader might drive aggressive timelines for reducing emissions, eliminating waste, or hitting ethical sourcing targets. When balanced with support and realism, this can accelerate progress and create a culture that values action over rhetoric. However, pacesetting leadership must be calibrated carefully in sustainability contexts. Unrealistic expectations or lack of emotional awareness can lead to burnout, undermining the long-term nature of sustainable work. Used judiciously, though, pacesetting leadership can raise the bar for what is expected and demonstrate that sustainability does not mean compromising on performance or quality; it means excelling with responsibility [

15].

Authoritative leadership, while often associated with rigidity, also has a strategic role in sustainability, especially in urgent or high-stakes scenarios. In times of crisis or when rapid alignment is required, authoritative leaders can make swift, decisive moves to implement sustainability mandates, address regulatory risks, or correct unethical practices. Their clarity and confidence can cut through inertia or confusion, particularly in organizations that are struggling to shift from legacy practices to more sustainable models. The key is moderation; used too often, this style can suppress innovation and create resistance [

4]. But when deployed in the right context, like responding to environmental compliance failures or steering the organization through a significant sustainability audit, it ensures that action is taken without delay, and that the commitment to sustainable standards is upheld with authority.

In line with Goleman’s paradigm, ref. [

16] stress that charismatic leaders play a crucial role in facilitating organizational sustainability by leveraging their personal appeal, vision, and ability to inspire and motivate others. They create a strong organizational culture, drive change, and foster innovation, all of which are essential for long-term sustainability. Organizational sustainability often requires change, whether it is adopting new technologies, shifting to more sustainable business practices, or rethinking strategies. Charismatic leaders are effective change agents. They encourage creativity and innovation, allowing the organization to adapt and evolve in a rapidly changing environment. This adaptability is essential for long-term sustainable survival and success. Sustainability is closely tied to ethical practices and social responsibility [

17]. Charismatic leaders often set high ethical standards and serve as role models for integrity and social responsibility. By fostering an environment that values ethics and sustainability, charismatic leaders help ensure that the organization’s practices align with its long-term sustainability goals [

17].

AI-empowered leadership enhances leadership capabilities, decision-making, and management practices within organizations by using AI tools and technologies, and is essential in navigating the complex landscape of sustainability. Leaders who strategically implement AI can guide their organizations toward more sustainable practices, achieve regulatory compliance, drive innovation, and create a positive impact on society and the environment [

18]. This requires a vision, investment in AI talent and technology, and a commitment to integrating sustainability into every facet of the organization. By harnessing artificial intelligence, these leaders can identify inefficiencies, monitor sustainability indicators in real-time, and facilitate informed scenario planning. This enables them to make proactive interventions that support regulatory compliance, reduce resource consumption, and drive innovation in sustainable business models. According to [

19], this approach can revolutionize leadership by offering predictive analytics and decision-support systems that enhance strategic planning and execution, especially regarding employee recruitment and talent acquisition. Implementing a balanced AI-human approach can augment human intelligence by providing virtual assistants, recommendation systems, and scenario planning tools that help leaders visualize potential sustainable outcomes and make better choices.

Table 2 below serves as a central analytical device that operationalizes the typology of leadership styles examined, directly linking theoretical constructs to their pragmatic implications for sustainability-embedded change management. By systematically contrasting eight principal leadership styles: visionary, coaching, affiliative, democratic, pacesetting, authoritative, charismatic, and AI-empowered, across key criteria related to both organizational performance and sustainability outcomes, the table provides an explicit framework for assessing how each style either advances or constrains sustainable change. This advances current understanding in several dimensions.

First, it moves beyond the frequent dichotomy of “effective versus ineffective” leadership by illustrating the nuanced ways in which specific styles can support or undermine long-term sustainability, depending on context, intensity, and sequencing. For example, while visionary and coaching styles are shown to foster long-term capability building and cultural buy-in essential for sustainable transformation, pacesetting and authoritative styles may deliver short-term results but risk exhaustion and reduced innovation if overapplied [

20].

Second, the table’s side-by-side format, integrated with the analytic discussion, enables scholars and practitioners to directly compare the trade-offs and complementarities among styles, thereby supporting a contingent approach to leadership selection as endorsed by this manuscript’s theoretical triangulation. Furthermore, by including emergent forms such as AI-empowered leadership, the typology addresses contemporary and future challenges, acknowledging technological disruption as both a risk and a strategic asset for sustainability.

Finally, the typology creates a bridge between leadership theory and practical change management by identifying style-specific levers and limitations for embedding sustainability objectives. This structured, comparative view informs actionable policy and leadership development decisions, moving the debate beyond abstract advocacy for “good leadership” toward a nuanced, evidence-based alignment of leadership practice with sustainability goals, and thus significantly enriches the empirical and conceptual rigor of the analytical framework presented in this article.

3.2. Critical Engagement with Contrasting Leadership Theories

While Daniel Goleman’s emotionally intelligent leadership paradigm offers a robust lens for understanding leadership in the context of sustainability-embedded change management, a deeper theoretical framing is achieved by situating Goleman’s approach in critical dialogue with alternative leadership theories, notably Complexity Leadership Theory and Authentic Leadership Theory. Goleman’s framework, widely cited for its practical utility, highlights the importance of six situational leadership styles which are visionary, coaching, affiliative, democratic, pacesetting, and authoritative, with each rooted in the leader’s emotional intelligence and ability to calibrate their approach to dynamic organizational circumstances [

16]. Emotional intelligence, as argued by Goleman and extended by subsequent research, equips leaders to foster trust, manage conflict, and inspire motivation, all of which are pivotal for navigating the uncertainties of organizational change and advancing sustainability initiatives. However, while Goleman’s model emphasizes individual adaptability and the leader’s capacity to align styles with organizational needs, it largely centers on the leader as a purposeful agent, shaping outcomes through intentional influence and personal skill [

3].

Contrastingly, Complexity Leadership Theory (CLT) emerges from the premise that modern organizations are not merely machines guided by top-down direction, but complex adaptive systems that self-organize in response to evolving internal and external pressures [

21]. From the CLT perspective, leadership resides not solely in the actions of designated individuals but is distributed throughout the organization, emerging from interactions among agents, teams, and networks. Leaders, therefore, serve less as controllers and more as facilitators or enablers, catalyzing adaptive capacity, fostering conditions for emergence, and nurturing informal dynamics that drive collective intelligence. This view challenges Goleman’s implicit assumption that leadership effectiveness is chiefly a matter of the individual’s emotional and interpersonal acumen; instead, CLT posits that leadership is a social and relational property, manifesting through the dynamic interplay of multiple actors embedded in complex systems [

22]. For sustainability-embedded change management, this theoretical expansion is vital: it foregrounds how leaders must not only motivate and engage, as Goleman prescribes, but also orchestrate contexts in which innovation, learning, and emergent practices thrive despite unpredictability. Complexity leadership thus underlines the limitations of a purely style-based, leader-centric approach and calls attention to the adaptive, network-oriented strategies necessary for deep, system-level sustainable transformation.

Authentic Leadership Theory (ALT) provides another compelling counterpoint by shifting analytical focus from style and adaptability to the moral and existential foundations of leadership practice. ALT argues that leadership effectiveness and sustainability outcomes are contingent upon the leader’s self-awareness, relational transparency, and sustained alignment with deeply-held ethical values. In contrast to Goleman’s instrumental focus on emotional intelligence as a functional asset, ALT asserts that only leaders who consistently embody authenticity, acting in ways congruent with their internal beliefs and open dialogue, will earn the trust required to mobilize enduring, value-based organizational change [

23]. This perspective is particularly resonant in the context of sustainability, where competing interests and ethical dilemmas abound. Authentic leaders legitimize change initiatives not merely by deploying the “right” style or managing relationships artfully, but by persuading stakeholders that change is grounded in a genuine moral commitment to environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and organizational integrity. Moreover, ALT underscores the transformative influence of moral modeling: leaders who disclose their values, admit their limitations, and foreground the ethical rationale for change foster cultures of openness, psychological safety, and engaged followership, which are critical precursors to sustainability success.

Synthesizing these theories with Goleman’s paradigm materially enriches the analytical depth of the change management framework presented in this research. While Goleman’s approach captures the need for situational flexibility and emotional acuity, CLT compels the analyst to attend to the broader systemic conditions and distributed agency that underpin effective, large-scale change. ALT, in turn, highlights the non-negotiable requirement of ethical authenticity, trust-building, and transparent communication, characteristics essential for the legitimacy and acceptance of sustainability-driven transformation. By triangulating these perspectives, the article resists the temptation of mono-paradigmatic explanation and instead articulates a multilevel, multidimensional understanding of leadership in sustainability contexts [

24]. Leaders, accordingly, must not simply shift styles in response to immediate cues, but serve as sensemakers in complexity, architects of emergent change, and steadfast role models of the sustainability values they wish to see embedded within their organizations.

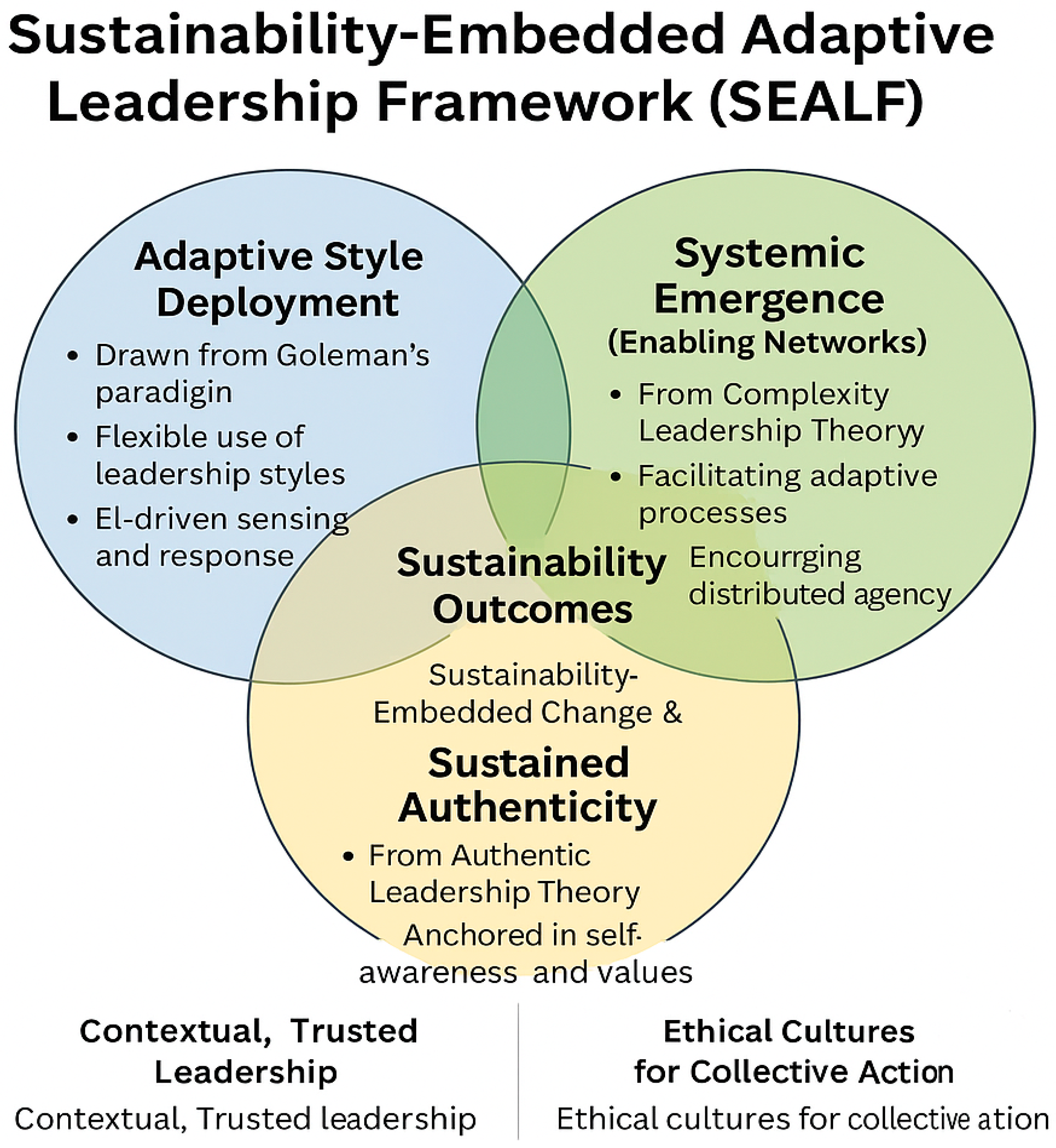

As seen in

Figure 2 below, building on the comparative analysis of leadership theories and their implications for sustainability outcomes, this research proposes a novel integrative model, namely the ‘

the Sustainability-Embedded Adaptive Leadership Framework (SEALF)’. The SEALF Venn diagram illustrates how adaptive style, systemic emergence, and sustained authenticity collectively intersect to drive sustainability-embedded organizational change and enduring positive impact. The SEALF synthesizes the strengths of Goleman’s emotional intelligence-based situational leadership, Complexity Leadership Theory’s emphasis on emergent, distributed agency, and Authentic Leadership Theory’s focus on moral self-awareness and values alignment. The framework posits that in dynamic, sustainability-oriented environments, leadership effectiveness does not derive from the application of any single style or paradigm but from the leader’s ability to fluidly move across three interconnected domains: adaptive style deployment, enabling of systemic emergence, and sustained authenticity. First, SEALF suggests leaders must assess contextual needs through emotionally intelligent sensing, deploying the appropriate leadership style (e.g., visionary, democratic, coaching) in response to specific sustainability challenges while remaining attuned to team and stakeholder sentiment. Second, the leader’s role extends beyond direct influence to cultivating networks that facilitate emergent solutions and distributed problem-solving [

25], reflecting Complexity Leadership’s insight that innovation often arises from informal interactions and adaptive processes rather than top-down control. Finally, SEALF anchors these activities in a foundation of authenticity: leaders must communicate openly about their sustainability intentions, model ethical conduct, and build trust through consistency between words and actions. The intersection of these three domains produces an iterative, feedback-driven process by which leaders, teams, and organizations continuously adapt and co-evolve in pursuit of sustainability outcomes. This original framework offers both a conceptual map and a practical guide for cultivating the kind of leadership that aligns short-term change management success with enduring, system-wide sustainability objectives.

3.3. What Makes for Sustainability-Embedded Leadership?

Leadership is a form of power that enables an individual to influence or transform the values, beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes of others [

26]. A person with strong leadership skills acts as an exemplary role model for their employees, as a leader who effectively achieves significant results earns the trust and admiration of their team. This, in turn, can lead to organizational sustainability, and a transformation in the employees’ values, beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes, as they tend to emulate the leader, highlighting the adage that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery [

27]. Ref. [

28] also supports this perspective, highlighting that leaders with strong leadership capabilities possess the ability to influence others to achieve the organization’s goals and objectives.

Sustainability-embedded leaders are recognized for their ability to provide clear direction, which fosters commitment and teamwork to achieve organizational sustainable goals and objectives [

26]. Successful leaders typically possess a well-defined vision, enabling them to identify and overcome obstacles that may hinder progress. This capability allows them to implement necessary changes effectively, thereby improving the company’s sustainability and adaptability in a dynamic business environment.

According to [

29], leadership is a process where leaders use their skills and knowledge to guide their team toward goals that align with the organization’s objectives. Furthermore, sustainability-embedded leadership is marked by essential traits such as passion, consistency, trust, and vision, qualities that are vital for building employee trust and achieving organizational sustainability. Ref. [

30] argue that sustainability-embedded leaders have a clear, compelling vision for the future. They set a strategic direction and help others understand and commit to the long-term sustainable objectives, which enables them to articulate ideas clearly, listen actively, and provide constructive feedback, while bridging gaps and ensuring alignment within teams. Simply put, trustworthiness and honesty are critical for leadership as integrity builds trust and credibility, fostering a culture of accountability, ethical behavior, and sustainability.

Selecting the appropriate leadership style is vital, as sustainability-embedded leadership involves more than just adopting various personas. It requires a deep understanding of each style’s unique dynamics and strategically applying them to the specific context. Following this logic, the constructs of efficacy and efficiency are incorporated into the analysis and discussion below.

On the one hand, sustainability-embedded leaders are adaptable, able to transition between styles effortlessly, guided by emotional intelligence and a strong commitment to steering their teams toward sustainability. The efficacy of a leadership style is influenced not only by the leader’s preferences but also by the context in which it is used. Efficacy in leadership refers to the capacity of a leader to produce a desired or intended result. It is about the ability to achieve goals, inspire followers, and drive the organization or team toward sustainable success. The focus is on the effectiveness of a leader in achieving outcomes, motivating the team, and making strategic decisions.

Efficiency, on the other hand, in leadership, is about the ability of a leader to achieve sustainable goals with the least amount of resources, time, and effort. It involves optimizing processes, minimizing waste, and ensuring that the organization runs smoothly. The focus is on how well a leader manages resources (e.g., time, people, money) to achieve goals without unnecessary waste [

31]. Therefore, skilled leaders understand the importance of adapting their approach to fit the specific circumstances they face. Following this line of research, we now turn to discuss how sustainability-embedded leadership can be achieved in managing change.

3.4. Sustainability-Embedded Leadership in Change Management

Change has always been a challenge for organizations, just as it has been a constant in human life. People often find change difficult because it disrupts their routines and pushes them out of their comfort zones, creating discomfort as they adapt to new behaviors [

32]. For example, a worker who is used to starting work at 9 a.m. might struggle if their supervisor suddenly requires them to start at 7 a.m., as they would need to break the ingrained habit of waking up later. Similarly, within an organization, if employees are accustomed to completing tasks in a specific order, such as from A to Z, altering this sequence to Z to A can be challenging for everyone to adjust to quickly.

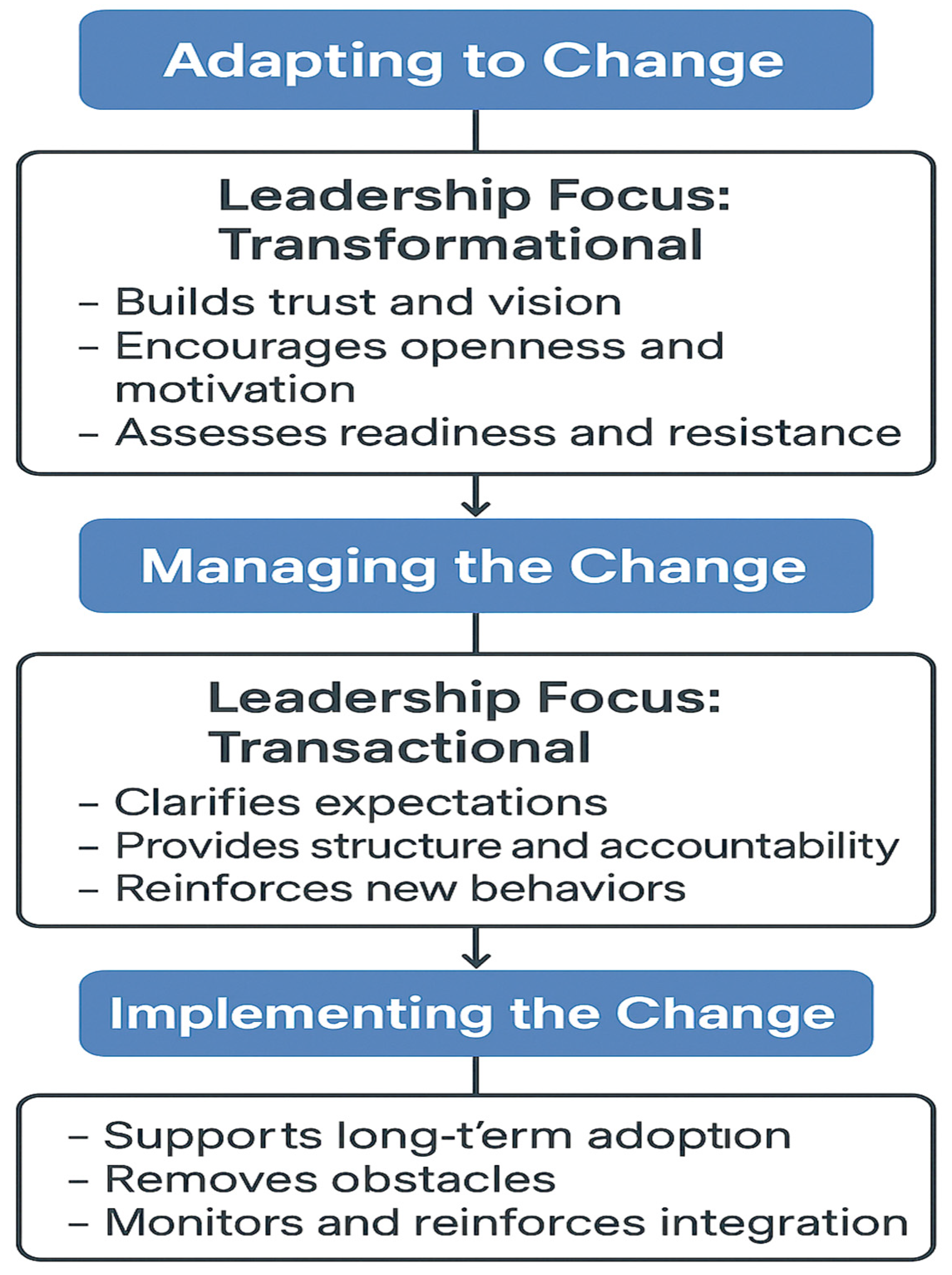

Change management within an organization is a strategy for guiding change at both organizational and individual levels, with each adapting in its own manner and at its own pace; when executed effectively, it enables an organization to capitalize on opportunities for gaining a competitive edge and achieving long-term sustainability [

15]. As seen in

Figure 3, below, the change management process includes three key stages: adapting to change, managing the change, and implementing the change. The first stage, adapting to change, assesses individual readiness and willingness to embrace the change, while the second stage focuses on managing and integrating the change into daily operations. Finally, the third stage, effecting the change, ensures that the change is sustained and becomes a natural part of organizational life [

2].

Sustainability-embedded leadership plays an important role in the design, development, and implementation of change management within an organization. Leaders who understand the nuances of change can significantly impact how smoothly and successfully change is adopted by the organization, fostering organizational sustainability. In designing change management, sustainability-embedded leaders articulate a clear and compelling vision for change, providing a roadmap that aligns with the organization’s sustainability and strategic goals. This helps in creating a strong foundation for the change management process [

33].

To develop change management strategies, sustainability-embedded leaders build coalitions of support by involving influential stakeholders who can champion the change effort across different levels of the organization. These change champions help drive momentum and enthusiasm for the change. Sustainability-embedded leaders can implement and sustain change by involving employees in decision-making processes, providing opportunities for skill development, fostering an environment that encourages innovation and adaptability, and embedding new behaviors and practices into the organization’s culture by recognizing and rewarding those who support and exhibit the desired changes [

34]. These strategies facilitate organizational sustainability.

Predicting the duration of change management within an organization is challenging due to the varying rates at which employees adapt. Some individuals may quickly embrace change, while others might need more time to adjust. Similarly, while some employees will welcome the change, others may resist it. Sustainability-embedded leaders must engage in clear communication and collaboration with their teams to ensure the sustainability-driven success of the change process [

35]. Leaders with strong and effective skills can motivate and influence employees, thereby facilitating successful organizational change and long-term sustainability. Ref. [

7] argue that without sustainability-embedded leadership, change is unlikely, as there would be no one to inspire, guide, and provide clear direction for the organization’s employees. Sustainability-embedded leadership is crucial for managing change, which is necessary for an organization to remain competitive in today’s business environment and achieve its goals.

Change is often uncomfortable, and some individuals may resist or deny it, risking obsolescence [

23]. Interest in leadership during change implementation is fundamentally about achieving organizational sustainability. To satisfy this interest, we must first understand what constitutes ‘sustainability-embedded leadership’ and how it contributes to organizational sustainability. From this perspective, sustainability-embedded leadership is achieved when it meets the needs for both completing tasks and maintaining group cohesion. Therefore, sustainability-embedded leadership is crucial for driving organizational change and achieving sustainability. Equally, sustainability-embedded leadership is vital in motivating and encouraging individuals to embrace and drive change toward sustainability. Leadership plays a key role in ensuring that employees adapt and contribute to the organization’s continuous and sustainable improvement and ability to thrive in a dynamic business landscape.

3.5. Concrete Examples of How Leaders Mitigated Resistance in Sustainability Initiatives

Leaders play a pivotal role in overcoming resistance during the implementation of sustainability initiatives, and both academic research and practical case studies provide ample evidence of effective strategies and tangible results. In organizations seeking to integrate sustainability into their core operations, resistance from employees, middle management, or even senior leaders is a common hurdle. This resistance can stem from skepticism, perceived costs, disruption to established routines, or uncertainty about long-term benefits. To successfully address these challenges, leaders have employed a variety of methods grounded in transparency, education, inclusivity, and transformational engagement [

36].

Organizations facing entrenched resistance at the middle-management level take a direct, engagement-focused approach. For instance, Circular Computing, a company championing eco-friendly technology solutions, experienced notable resistance from its management team when embarking on a sustainability-focused transformation. The leadership responded by combining proactive advocacy with concrete demonstration of value: they integrated compelling sustainability goals into performance appraisals, encouraged managers to lead innovation circles exploring operational improvements, and involved skeptics directly in pilot projects. By positioning managers as co-owners rather than mere implementers, resistance was reframed as involvement, and the visible endorsement by senior leaders reinforced the strategic importance of sustainability. A case narrative highlights, “Being assertive, proactive, and unwavering in the pursuit of a sustainable future can overcome these barriers. The narrative needs a shift from gentle persuasion to compelling, confident leadership” [

37].

Noteworthy is also the experience of Unilever under former CEO Paul Polman, who championed the Sustainable Living Plan as a fundamental business strategy [

37]. Polman’s approach was to embed sustainability into every unit and function of the business, pairing visionary leadership with relentless communication and employee empowerment. He frequently addressed concerns openly during town halls, fostering a culture where questioning and feedback were inputs for refining strategy rather than obstacles to be overcome. By integrating sustainability KPIs into bonus schemes and performance metrics, the leadership created clear incentives while neutralizing the perception that sustainability was a peripheral or idealistic agenda. “Sustainability is not a choice we make, but a way of operating that defines our future relevance,” Polman emphasized, underscoring the role leadership plays in translating vision into shared urgency.

The academic literature [

2,

36] further reinforces these case findings, with research arguing that leaders who anticipate resistance, rather than react to it, tend to be more successful. Strategies such as involving employees meaningfully in design and decision-making, communicating the purpose repeatedly and through varied channels, and leveraging feedback loops are consistently cited as best practices. For instance, as argued by [

2], he highlighted resistance to waste reduction initiatives was met by inviting operational staff to co-design process adjustments, which led not only to smoother adoption but also to innovative ideas from those closest to the shop floor. Leaders supported these efforts by providing emotional and technical resources, such as coaching, peer mentoring, and opportunities for hands-on learning, which increased ownership and reduced fear of job loss or skill redundancy.

Another effective tactic is the use of inclusive, democratic leadership, where employees are treated as change partners rather than subjects. Case studies [

36] show that by forming cross-functional sustainability teams and rotating leadership roles within these teams, organizations mobilize diverse perspectives, reduce silos, and foster collective problem-solving. Open forums and structured feedback mechanisms allowed employees to voice concerns, suggest adjustments, and see their contributions reflected in the evolving sustainability agenda, which was critical to shifting mindsets from resistance to engagement. Leaders also addressed root causes of resistance by transparently discussing trade-offs, responding to concerns about short-term costs versus long-term gains, and sharing external examples of industry best practices to provide external validation.

Where financial or resource-based resistance was significant, successful leaders framed sustainability not as a compliance exercise but as a driver of long-term business value. For example, according to a recent report by McKinsey [

33], Company B, in a well-documented rollout of energy efficiency programs, faced initial pushback over capital investments and disruption to operational routines. Leaders countered this by piloting small-scale projects, openly sharing ROI data, and involving resisters in measuring and reporting positive outcomes such as cost savings or enhanced safety. Over time, the visible, data-driven successes moved doubters to advocates, and the organization’s leadership became a visible sponsor of further innovation. In sum, leaders mitigate resistance to sustainability through an adaptive blend of clear vision, educational engagement, empathetic listening, inclusion, visible sponsorship, and the strategic use of quick wins that build credibility. Through these concrete methods, evident across sectors, they not only dismantle barriers but also turn resistance into momentum for lasting change.