Are Entitlements Enough? Understanding the Role of Financial Inclusion in Strengthening Food Security

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Objectives

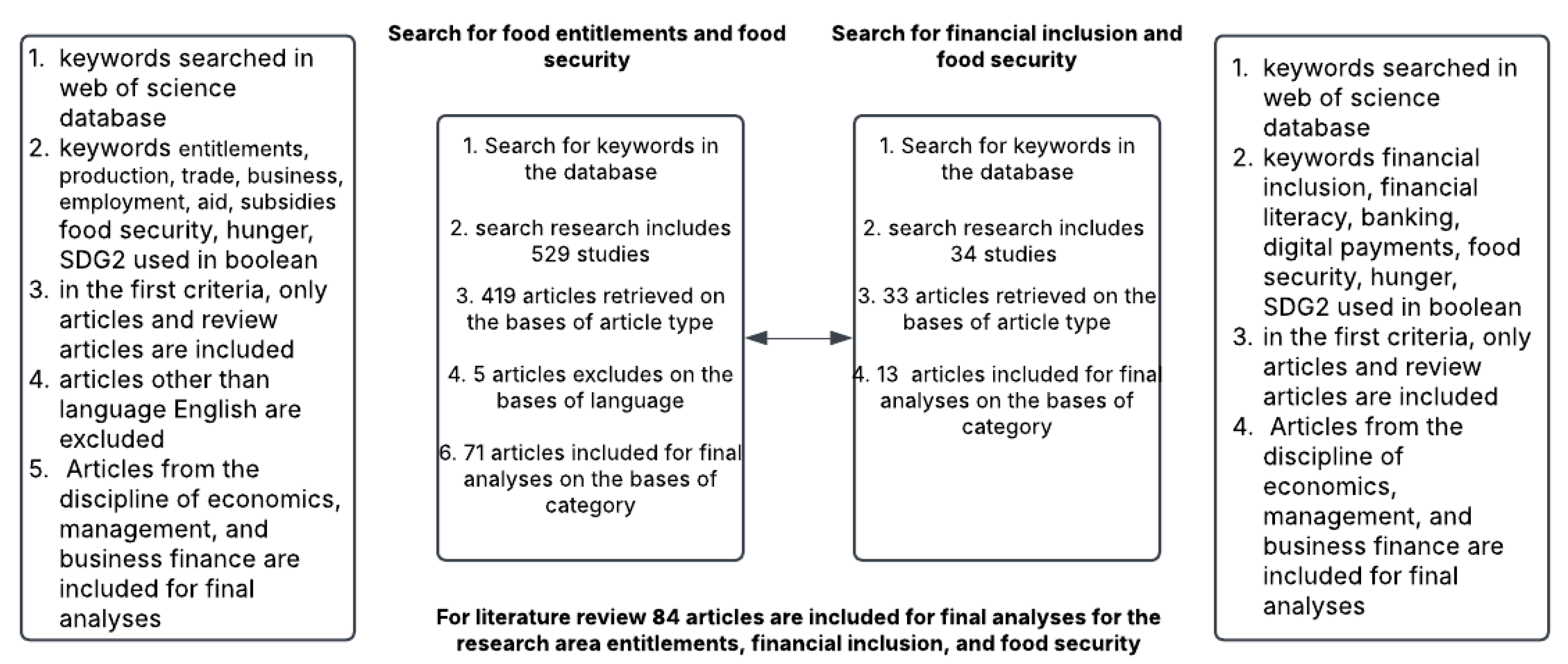

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Findings

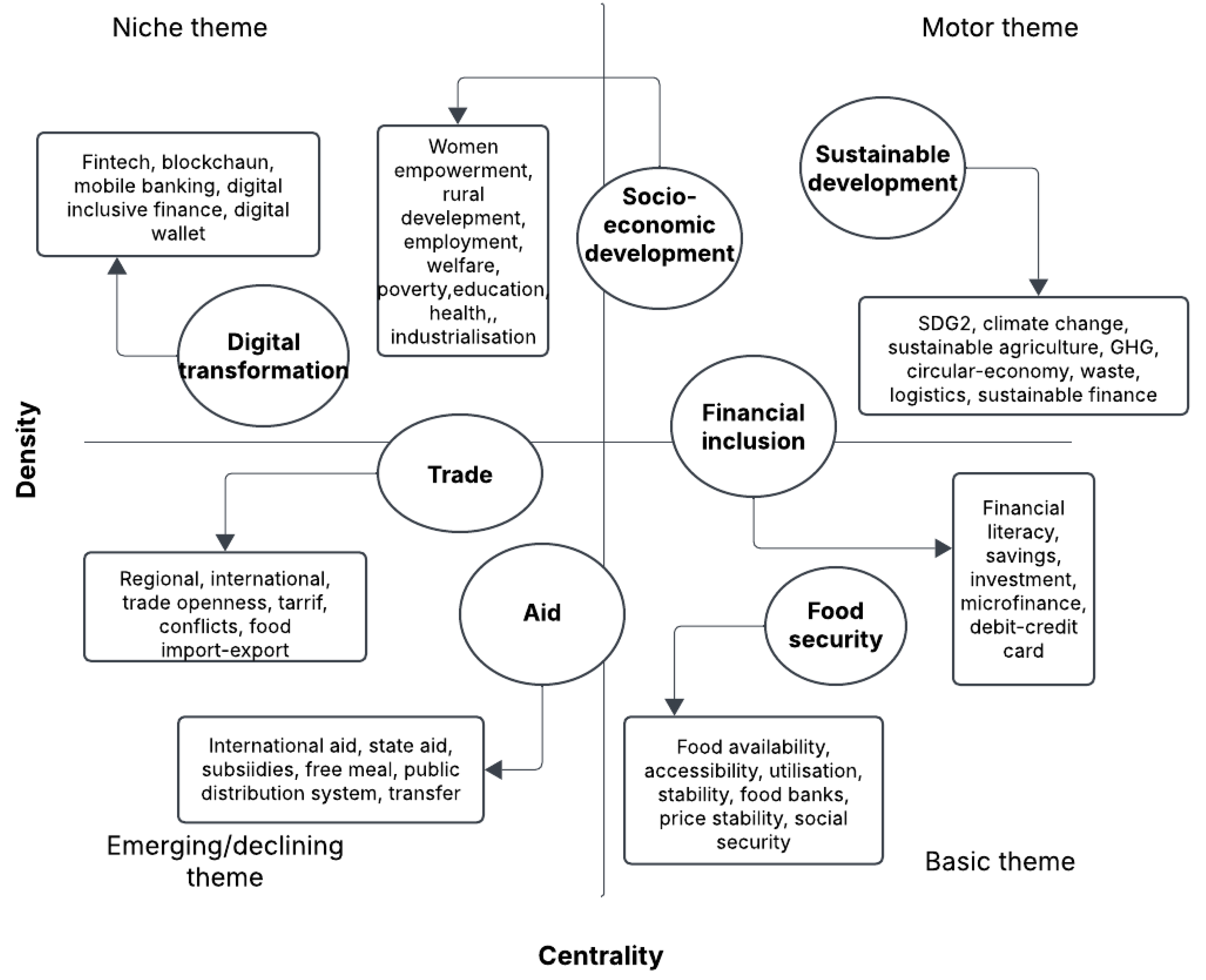

3.1. Thematic Map

3.1.1. Sustainable Development

3.1.2. FI and Digital Transformation

3.1.3. Socio-Economic Development

3.1.4. Trade

3.1.5. Aid

3.1.6. FS

| Overall Theme | Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | Control Variables | Methods | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Development | Digital FI, Digital technology, Fintech | Land green utilization efficiency, sustainable agriculture, SDGs, | Human capital, physical capital, and income disparity | Quantitative using regression and SEM | DFI improves land’s green utilization efficiency, and Digital technology helps in increasing sustainable agriculture | [81,82,83,84,85] |

| Socio-economic development | Saving accounts, FI | Nutrition, household welfare | Age, education, household size, and business size, | Quantitative analysis using surveys and regression | FI reduces the gender gap in female- and male-headed households, using mobile money, welfare impacts greater on the male-headed household in terms of food availability, and food quality in terms of the female-headed household. | [67,82,86] |

| FI | Saving accounts, formal credit, and FI | Nutrition, household welfare, FS | Age, education, household size, and business size | Quantitative analysis using regression | FI reduces the gender gap between female- and male-headed households. | [24,67,81,83,84,86,87] |

| FS | Digital FI, Digital technology, Fintech, export, import, food aid | FS, nutrition, household welfare, and sustainable agriculture | Age, education, urbanization, household size, and business size | Quantitative analysis using a survey and regression | Using mobile money enhances welfare. Agriculture export promotion affects FS. Food ai | [67,81,82,86] |

| Trade | Agricultural export promotion, regional trade, and trade liberalization | FS | N/A | Quantitative analysis | Agriculture export promotion affects FS in urban areas. Intra-trade leads to enhanced FS. Trade liberalization enhances national FS by increasing food supply. | [8,88,89] |

| Aid | Food aid, social security benefits, | Food production and supply, FS, Household FS | N/A | Quantitative analysis using a survey and regression | Social security benefits decrease the FS at an early entitlement age. Food aid reduces food expenditure and provides FS. | [90,91,92] |

| Digital Transformation | Digital inclusive finance, FI, digital technology, Fintech | FS, Household welfare, sustainable technology, SDGs | Imports, GDP, education, infrastructure, Human capital, physical capital, income disparity, | Fixed-effect models, Regression analysis | Digital inclusive finance can promote multi-dimensional FS. It improves the land’s green utilization efficiency. Using mobile money greater welfare impact on the male-headed household in terms of food availability and food quality, terms to the female-headed household. Digital technology helps in increasing sustainable agriculture. | [24,81,83,84,86] |

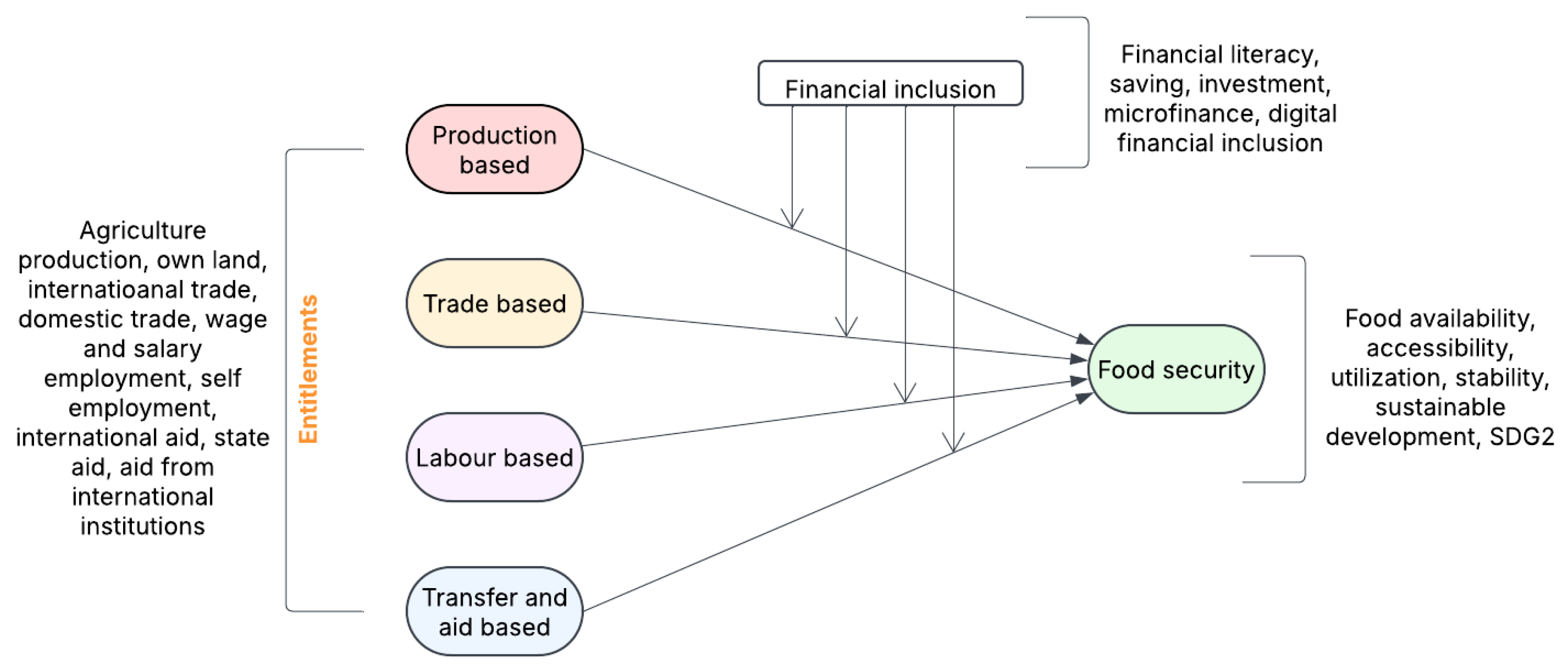

3.2. Conceptual Framework

4. Future Research Directions

5. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Wesselbaum, D.; Smith, M.D.; Barrett, C.B.; Aiyar, A. A Food Insecurity Kuznets Curve? World Dev. 2023, 165, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Choubey, V.K.; Raut, R.D.; Jagtap, S. Enablers to Achieve Zero Hunger through IoT and Blockchain Technology and Transform the Green Food Supply Chain Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 136894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosegrant, M.W.; Sulser, T.B.; Wiebe, K. Global investment gap in agricultural research and innovation to meet Sustainable Development Goals for hunger and Paris Agreement climate change mitigation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 965767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023; International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy, 2023; ISBN 9789251372265. [Google Scholar]

- Funke, S.M.; Akanbi, I.D.; Kikelomo, O.K.; Faruq, L.T.; Abdulazeez, S.A. Financial Literacy, Food Security, and Farmers’ Mental Health in Rural Nigeria: Insights from the Cashless Policy Enactment. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241301828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesclaros, J.M.L. Changing the Narrative of ASEAN Progress in Addressing Hunger: ‘Snoozing’ the Alarm for SDG #2? Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1283–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragie, E.; Balie, J.; Morales, C.; Pauw, K. Synergies and Trade-Offs between Agricultural Export Promotion and Food Security: Evidence from African Economies. World Dev. 2023, 172, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Murillo, F.; Armentia-Vizuete, J.I.; Marauri-Castillo, I.; Rodríguez-González, M.D.M. Food Accessibility on Digital Press: Framing and Representation of Hunger in Spain. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2020, 2020, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E. Remote Sensing Technology and Land Use Analysis in Food Security Assessment. J. Land Use Sci. 2016, 11, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthus, T.R. An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798). Work. Thomas Robert Malthus Lond. Pick. Chatto Publ. 1986, 1, 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- Drèze, J.; Sen, A. Political Economy of Hunger: Volume 1: Entitlement and Well-Being; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Poverty and Famines; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1983; ISBN 0198284632. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Capability and Well-Being73. Qual. Life 1993, 30, 270–293. [Google Scholar]

- Sen Amratya, D.J. Hunger and Public Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; ISBN 0198283652. [Google Scholar]

- Potocki, T. Locating Financial Capability Within Capability Approach—Theoretical Survey. Pol. J. Econ. 2022, 1, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storchi, S.; Johnson, S. Financial Capability for Wellbeing: An Alternative Perspective from the Capability Approach; University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, J.I.; Zenker, J.; Filipiak, U.; Movsisyan, A.; Cluver, L.D.; Shenderovich, Y. Do Saving Promotion Interventions Increase Household Savings, Consumption, and Investments in Sub-Saharan Africa? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Dev. 2018, 104, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Chen, C.; Chen, F. Consumer Financial Capability and Financial Satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, F.; De Muro, P. From Food Availability to Nutritional Capabilities: Advancing Food Security Analysis. Food Policy 2016, 60, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; IDS: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Sahu, T.N. Targeting Zero Hunger to Ensure Sustainable Development: Insights from a Panel Structure. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 2814–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Z.Z.A.; Badeeb, R.A.; Philip, A.P. Financial Inclusion, Poverty, and Income Inequality in ASEAN Countries: Does Financial Innovation Matter? Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 169, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowowe, B. Financial Inclusion, Gender Gaps and Agricultural Productivity in Mali. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2025, 29, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I.; Asongu, S.A.; Acheampong, A.O. Financial Inclusion and Food Insecurity: Examining Linkages and Potential Pathways. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 418–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Ren, X.; Huang, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q. A Study of the Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Multidimensional Food Security in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1325898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murendo, C.; Murenje, G.; Chivenge, P.P.; Mtetwa, R. Financial Inclusion, Nutrition and Socio-Economic Status Among Rural Households in Guruve and Mount Darwin Districts, Zimbabwe. J. Int. Dev. 2021, 33, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, M.A.; Essilfie, G.; Ntiamoah, E.B.; Xu, H.; Jiang, Y. Assessing Financial Literacy and Food and Nutritional Security Relationship in an African Country. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millimet, D.L.; McDonough, I.K.; Fomby, T.B. Financial Capability and Food Security in Extremely Vulnerable Households. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 1224–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machili, T. Financial Inclusion and Food Security Nexus. Sothern Afr. Towar. Incl. Econ. Dev. 2021, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Iskander, D.; Picchioni, F.; Zanello, G.; Guermond, V.; Brickell, K. Sick of Debt: How over-Indebtedness Is Hampering Health in Rural Cambodia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 367, 117678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Economist Group. Global Food Security Index (GFSI); Economist Intelligence Unit: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 10, ISBN 9789251399378. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, C. Sustainable Development Goals, Financial Inclusion, and Grain Security Efficiency. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katia, V. Financial Inclusion for Direct Benefit Transfer Growth and Hurdles. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Res. 2013, 3, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. Trade Rules, Food Security and the Multilateral Trade Negotiations. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2014, 41, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbite, O.O.; Machethe, C.L. Bridging the Financial Inclusion Gender Gap in Smallholder Agriculture in Nigeria: An Untapped Potential for Sustainable Development. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunisch, S.; Denyer, D.; Bartunek, J.M.; Menz, M.; Cardinal, L.B. Review Research as Scientific Inquiry. Organ. Res. Methods 2023, 26, 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Schnell, J.; Adams, J. Web of Science as a Data Source for Research on Scientific and Scholarly Activity. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, M.; Casper Ferm, L.E.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P.; Ngo, L. The Dark Side of Artificial Intelligence in Marketing: Meta-Analytics Review. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 1234–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Nangia, P.; Singh, S. Where’s Our Share: Agenda for Gender Representation in Mining Industry. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Veith, C.; Dobrea, R.C. Artificial Intelligence And Competency-Based Education: A Bibliometric Analysis. Amfiteatru Econ. 2024, 26, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.Y.; Hew, J.J.; Wong, L.W.; Lin, B.S. The Past and beyond of Mobile Payment Research: A Development of the Mobile Payment Framework. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 1757–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Panigrahi, P.K.; Arya, V. Analysis of Artificial Intelligence-Based Technologies and Approaches on Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; bin Abu Bakar, Z. Understanding and Facilitating Sustainable Agricultural Practice: A Comprehensive Analysis of Adoption Behaviour among Malaysian Paddy Farmers. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.H.; Glauber, J.W. Trade, Policy, and Food Security. Agric. Econ. 2020, 51, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntawuruhunga, D.; Ngowi, E.E.; Mangi, H.O.; Salanga, R.J.; Shikuku, K.M. Climate-Smart Agroforestry Systems and Practices: A Systematic Review of What Works, What Doesn’t Work, and Why. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 150, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Pagani, F.; Banja, M.; Muntean, M.; Schaaf, E.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Becker, W.; Quadrelli, R.; Risquez Martin, A.; et al. JRC Science for Policy Report; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; ISBN 978-92-68-20572-3. [Google Scholar]

- Poponi, S.; Arcese, G.; Ruggieri, A.; Pacchera, F. Value Optimisation for the Agri-Food Sector: A Circular Economy Approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 2850–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidogeza, J.-C.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; De Graaff, J.; Lansink, A.O. Potential Impact of Alternative Agricultural Technologies to Ensure Food Security and Raise Income of Farm Households in Rwanda. Forum Dev. Stud. 2015, 42, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Nunez, A. Responding to Climate Change in Tropical Countries Emerging from Armed Conflicts: Harnessing Climate Finance, Peacebuilding, and Sustainable Food. Forests 2018, 9, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikis, J.; Saraji, M.K. Green Productivity and Undesirable Outputs in Agriculture: A Systematic Review of DEA Approach and Policy Recommendations. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2022, 35, 819–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.H.B.A.; Yasin, R. Bin Children Rights to ‘Zero Hunger’ and the Execution Challenges during the COVID-19 Crisis. Hasanuddin Law Rev. 2022, 8, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerssa, G.; Feyssa, D.; Kim, D.-G.; Eichler-Löbermann, B. Challenges of Smallholder Farming in Ethiopia and Opportunities by Adopting Climate-Smart Agriculture. Agriculture 2021, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Zheng, L. Why Is It Necessary to Integrate Circular Economy Practices for Agri-Food Sustainability from a Global Perspective? Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Mao, H. The Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion on Relative Poverty Among Urban Households: A Case Study on China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.T. The Effects of Risk Appraisal and Coping Appraisal on the Adoption Intention of M-Payment. Int. J. BANK Mark. 2020, 38, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florey, C.; Hellin, J.; Balié, J. Digital Agriculture and Pathways out of Poverty: The Need for Appropriate Design, Targeting, and Scaling. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2020, 31, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Chang, L.E.I. Role of Financial Technology on Poverty Alleviation in Asian Countries: Mediating Role of Institutional Quality. Singapore Econ. Rev. 2023, 68, 1251–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, A.; John, M.; Potdar, V. Achieving UN SDGs in Food Supply Chain Using Blockchain Technology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Analyzing the Direct Role of Governmental Organizations in Artificial Intelligence Innovation. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 437–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, E.H. Food Security: What Does Gender Have to Do with It? Agenda 2016, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Girls’ Education. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/education/girls-education (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Biru, W.D.; Zeller, M.; Loos, T.K. The Impact of Agricultural Technologies on Poverty and Vulnerability of Smallholders in Ethiopia: A Panel Data Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 147, 517–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutenje, M.; Kankwamba, H.; Mangisonib, J.; Kassie, M. Agricultural Innovations and Food Security in Malawi: Gender Dynamics, Institutions and Market Implications. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 103, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, N.; Avula, R.; van den Bold, M.; Becker, E.; Nisbett, N.; Haddad, L.; Menon, P. What Will It Take to Accelerate Improvements in Nutrition Outcomes in Odisha? Learning from the Past. Glob. Food Sec. 2017, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, C.D.; Zhuang, J. Rural Poverty Alleviation Strategies and Social Capital Link: The Mediation Role of Women Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020925504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.B.; Nsabimana, A. Financial Inclusion and Nutrition among Rural Households in Rwanda. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2024, 51, 506–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.W.; Kayani, A.S.; Alotaibi, J.M.; Muddassir, M.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Kassem, H.S. Regional Trade and Food Security Challenges: The Case of SAARC Countries. Agric. Econ. Ekon. 2020, 66, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Braun, J.; Birner, R. Designing Global Governance for Agricultural Development and Food and Nutrition Security. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2017, 21, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. UNCTAD-WHO Analysis Reveals Trends in Processed Foods Trade; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Gilmour, B.; Dang, H. Promise, Problems and Prospects: Agri-Biotech Governance in China, India and Japan. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2017, 9, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huo, W.; Zhu, L. Does Digital Financial Inclusion Have an Impact on High-Quality Development of Trade? Evidence from China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 788–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I.; Churchill, S.A. Ethnic Diversity and Food Insecurity: Evidence from Ghana. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 1912–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Jia, N.; Lin, F. Quantifying the Impact of Russia-Ukraine Crisis on Food Security and Trade Pattern: Evidence from a Structural General Equilibrium Trade Model. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, N.; Banovic, N. Exposing Error in Poverty Management Technology: A Method for Auditing Government Benefits Screening Tools. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo Barros, G.S.; Aparecido Alves, L.R.; Osaki, M. Biofuels, Food Security and Compensatory Subsidies. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2010, 2, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorano, B.; Sanfilippo, M. Innovative Features in Poverty Reduction Programmes: An Impact Evaluation of Chile Solidario on Households and Children. J. Int. Dev. 2012, 24, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.; Khan, A.; Suri, V.R.; Azam, R.; Salim, F. Between Hunger and Contagion: Digital Mediation and Advocacy during the COVID-19 Emergency in Delhi. Third World Q. 2024, 45, 946–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccone, D. Can the Covid19 Pandemic Affect the Achievement of the ‘Zero Hunger’ Goal? Some Preliminary Reflections. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2021, 22, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollakota, K.; Pick, J.B.; Sathyapriya, P. Using Technology to Alleviate Poverty: Use and Acceptance of Telecenters in Rural India. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2012, 18, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H. Digital Financial Inclusion, Cultivated Land Transfer and Cultivated Land Green Utilization Efficiency: An Empirical Study from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, K. Can Digital Technology Promote Sustainable Agriculture? Empirical Evidence from Urban China. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2282234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Ghosh, C.; Thenmozhi, M. Impact of Fintech and Financial Inclusion on Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Cross Country Analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 72, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, U. Mapping of FinTech Ecosystem to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Saudi Arabia’s Landscape. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert, M.; Dudek, M.; Sala, D. Surface Quality as a Factor Affecting the Functionality of Products Manufactured with Metal and 3D Printing Technologies. Materials 2024, 17, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulbah, F.F.B.; Olumeh, D.E.; Mantey, V.; Ipara, B.O. Impact of Financial Inclusion on Household Welfare in Liberia: A Gendered Perspective. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2025, 29, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombo, W.; Sohn, W. The Effect of Formal Credit on Household Welfare in Malawi. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasdorp, G. Regional Trade and Food Security in SADC. Food Policy 1998, 23, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorosh, P.A. Trade Liberalization and National Food Security: Rice Trade between Bangladesh and India. World Dev. 2001, 29, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballenger, N.; Mabbszeno, C. Treating Food Security and Food Aid Issues at the Gatt. Food Policy 1992, 17, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, P. The Effect of Social Security Benefits on Food Insecurity at the Early Entitlement Age. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2023, 45, 392–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusiime, H.A.; Renard, R.; Smets, L. Food Aid and Household Food Security in a Conflict Situation: Empirical Evidence from Northern Uganda. Food Policy 2013, 43, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowowe, B. The Effects of Financial Inclusion on Agricultural Productivity in Nigeria. J. Econ. Dev. 2020, 22, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapanje, O.; Karuaihe, S.; Machethe, C.; Amis, M. Financing Sustainable Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Role of Financial Technologies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzante, S.; Labarta, R.; Bilton, A. Adoption of Agricultural Technology in the Developing World: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, J.; Wu, X. Financial Inclusion, Education, and Employment: Empirical Evidence from 101 Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakanko, M.A. Financial Inclusion and Women Participation in Gainful Employment: An Empirical Analysis of Nigeria. Indones. J. Islam. Econ. Res. 2020, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzanku, F.M. Food Security in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the Nexus between Gender, Geography and off-Farm Employment. World Dev. 2019, 113, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Core Idea | Philosophy | Key Proponent | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Needs Approach | Ensuring food availability through welfare programs | Government intervention to provide minimum food requirements | ILO | Public Distribution System (PDS) UN World Food Programme (WFP) |

| Malthusian Approach | Hunger results from population growth outpacing food production | Food production grows arithmetically; population grows exponentially | Thomas Malthus | birth control policies and agriculture expansion |

| Entitlement Approach | Hunger occurs due to a lack of purchasing power, not food shortages | People must have the economic means to buy food | Amartya Sen | cash transfer programs and employment guarantees (e.g., MGNREGA in India) |

| Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA) | Strengthening assets and livelihood strategies for food access | Holistic development of human, natural, and financial capital | Robert Chambers & Gordon Conway | microfinance programs, climate-resilient farming, and community-led food security |

| Capability Approach | Food security depends on individual capabilities and freedoms | Enhancing human potential rather than just providing food | Amartya Sen | shifted focus to human development, social justice, and women’s empowerment |

| Author | Review Scope | Key Contributions | Limitations | Focus Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Availability | Food Accessibility | Food Utilization | Food Stability | ||||

| [35] | The study reviews the role that trade can play in promoting FS and examines the evidence on some of the criticisms and concerns that are often voiced. | The paper suggests making international trade system more efficient and resilient so that it can face the threats against FS. The domestic policies should be formed in a way that enhance socio-economic development while contributing to the FS and international trade. | The research focuses mostly on global trade mechanisms, not adequately investigating the impact of local and regional food systems in improving FS. | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| [18] | The study reviews 27 randomized controlled trials on the saving promotion program for meta-analysis. | The paper provides mobile banking is most effective in accelerating savings in rural areas, especially in remote areas due to lesser need to depend on bank branches. Furthermore, Future saving promotion initiatives should target both male and female family heads to achieve consensus on financial management and budgeting changes. | The study focuses only 27 literatures with time period of sixteen months. Additionally, sample includes majorly male entrepreneurs and farmers. There is a need to add poor or less privileged people in the sample. | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| [36] | The study uses quantitative and qualitative mixed method reviews. For secondary databases are used and literature reviews are used for qualitative analyses to assess the FI gender gap in Nigeria. | The study suggests that reasons behind the FI gender gap are cultural, socio-economic, and legal factors. It affects productivity enhances income inequality, poverty, food insecurity, and poverty. Promoting measures like digital FI do not just help in closing the gender gap but in achieving other SDGs too, such as SDG1, SDG2, and SDG5. | The limitation of the study is it relies on secondary data for review that may not be capture real time trends. | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| [20] | The study reviews different approaches to FS in academics and proposed in academics and international organisations. | The study suggests approaches to measure FS covering all the aspects of the basic need of food stability. The study also contributes by providing suggestions regarding developing scales and databases to measure food utilization especially at individual levels. | The study does not account for the impact of governance, policies, and institutional constraints on FS. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| This Study | This study reviews 97 literature empirical and review both. It includes literature entitlements and FS, and FI and FS. | The study suggests that FI plays a major role in determining FS. It works as a moderator between entitlements and FS. FI increases the effectiveness of these rights, minimizes vulnerabilities, and improves FS outcomes. | The study’s limitation is it focus mainly on entitlements given by entitlement theory. Additionally, from part of capability theory it highlights only financial capabilities not others such as health, education. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sr No. | Research Area | Research Question |

| 1 | FS |

|

| 2 | Sustainable development |

|

| 3 | FI |

|

| 4 | Digital transformation |

|

| 5 | Socio-economic development |

|

| 6 | Trade |

|

| 7 | Aid |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chanaliya, N.; Bansal, S.; Cichoń, D. Are Entitlements Enough? Understanding the Role of Financial Inclusion in Strengthening Food Security. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177954

Chanaliya N, Bansal S, Cichoń D. Are Entitlements Enough? Understanding the Role of Financial Inclusion in Strengthening Food Security. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177954

Chicago/Turabian StyleChanaliya, Nisha, Sanchita Bansal, and Dariusz Cichoń. 2025. "Are Entitlements Enough? Understanding the Role of Financial Inclusion in Strengthening Food Security" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177954

APA StyleChanaliya, N., Bansal, S., & Cichoń, D. (2025). Are Entitlements Enough? Understanding the Role of Financial Inclusion in Strengthening Food Security. Sustainability, 17(17), 7954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177954