Life Cycle Assessment of Spring Frost Protection Methods: High and Contrasted Environmental Consequences in Vineyard Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PTO Case Study

2.2. ASFPMs of Loire Valley

- -

- Wind machines—these infrastructures mix air from higher altitude with the colder air near the ground during spring frost events. Rather than significantly raising temperatures, they slow the natural cooling process of the surface layer [32]. Wind machines are available in both mobile (MWM) and fixed (FWM) models, with the former serving as a semi-permanent solution and the latter offering long-term frost protection. These machines can be powered by thermal engines (FWM1, FWM3, FWM4, MW2), electric motors (MW1), gas engines (FWM2), or even connected directly to a tractor’s power take-off. Wind machines are often used alongside antifrost candles or small heaters filled with combustibles to enhance protection (FWM1, FWM2, MWM1, MWM2). In some cases, a burner is placed in front of the machine to preheat the air before it is circulated downward by the propellers (FWM4). However, trials have shown inconsistent results in terms of temperature gain from this additional heating method [33]. These systems can be manually controlled or equipped with automatic activation.

- -

- Sprinklers (S), while originally designed for irrigation, are also used to coat vine buds with water before temperatures drop below freezing. As the water freezes, it releases latent heat, helping to maintain the bud temperature at 0 °C or above. Additionally, the resulting ice layer provides insulation, preventing severe frost damage, generally occurring from −4 to −1 °C depending on the phenological stage of the bud. While sprinklers can be automated, their effectiveness depends on precise mesoclimatic conditions and a continuous water supply, making automated activation potentially risky. This method requires a permanent underground piping system along with a semi-permanent overground irrigation setup.

- -

- Antifrost candles (ACs), lit at the last moment, are used to warm the air around vine buds. A large number of candles are required for effective protection, with approximatively 350 candles per hectare in the Loire Valley, depending on frost severity. This method requires continuous monitoring during use but offers a quick and flexible solution, as no prior installation is needed before spring frost events.

- -

- Heating cables (HCs) correspond to electric (HC1) or radiative (HC2) cables attached to the vine wires close to the bud zone that generate heat through electrical conductivity, warming the surrounding area within a 5 to 10 cm radius. They must be connected to a control unit powered either by a generator or the national electric grid. This solution can be semi-permanent, requiring full installation and removal before and after the spring frost period, or partially permanent, where an underground system remains in place and is connected to the national grid.

- -

- Heaters are metal containers designed to burn fuel (H1), wood (H2), or peat (H3), generating warmth to protect vine buds from frost. Each heater lasts for approximately 25 uses before needing to be replaced, with around 180 heaters needed per hectare in the Loire Valley. Heaters must be installed before frost events and require continuous monitoring during their application to ensure effectiveness.

- -

- Winter cover (WC) is a protective layer that covers one or two rows of vines and is secured to adjacent rows with elastics. Together, these layers form a cover over the entire plot, helping to retain daytime warmth and prevent frost damage. The plastic layer reflects the radiative heat from the soil toward the vines. If windspeed exceeds 12 m/s, the winter protection needs to be folded around the vine trellis wires to prevent damage to the elastic, cover, and trellis system. Such windspeed combined with temperatures below 0 °C usually occurs only during advective frost. Therefore, this semi-permanent system is primarily designed to protect vines against radiative frost.

2.3. PTO Subsystems

- -

- Soil used by the vineyard: Covers the planted surface area and adjacent zones utilized for tractor movement.

- -

- NP trellis infrastructure and installation: Includes all materials installed in the vineyard, along with the associated manual and mechanical operations required for installation.

- -

- NP other operations: Encompasses all mechanical and manual operations conducted in the young vineyard, including mechanical and chemical soil management, pruning, other manual operations, phytosanitary treatments (including both active pesticide ingredients and machinery operations), and fertilization (including both fertilizers and machinery operations).

- -

- NP pesticide emissions: Includes the on-field emissions of pesticide active ingredients.

- -

- NP nutrient emissions: Encompasses on-field emissions of phosphorus and nitrogen.

- -

- NP heavy metal emissions: Covers on-field emissions of cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, lead, zinc, and mercury resulting from fertilizer applications and atmospheric deposition.

- -

- Other occasional operations: Includes mechanical and manual operations occurring less than once per year, such as soil decompaction.

- -

- Fertilizing operations: Covers the production of fertilizers and soil improvers used, along with the associated operation for their on-field application.

- -

- P nutrient emissions: Includes the same elements and applies the same models as described in the subsystem “NP nutrient emissions”.

- -

- P heavy metal emissions: Encompasses the same elements as the subsystem “NP heavy metal emissions”.

- -

- P mechanical soil management: Covers all machinery operations for soil tillage and mechanical weeding.

- -

- P manual operations: Includes worker transportation from the farm to the vineyard plots.

- -

- P other mechanical operations.

- -

- P phytosanitary treatment operations: Encompasses the manufacturing and transport of pesticides, along with the associated operations for their on-field application.

- -

- P pesticide emissions: Covers the same elements as the subsystem “NP pesticide emissions”.

- -

- P harvest mechanical operations: Includes harvester, tractors, and trailer operations.

2.4. ASFPM Subsystems

- -

- Application: Encompasses direct emissions from water and energy consumption, as well as their production processes, including extraction, treatment, refining, and fuel combustion associated with equipment use.

- -

- Equipment manufacturing: Covers the production and disposal of all equipment used for ASFPMs, including paraffin for antifrost candles.

- -

- Transport: Accounts for the transportation of materials.

- -

- Implementation and removal: Includes all operations and resources required for installing and removing the ASFPM in the field, along with the transportation of human labor from the farm to the vine plot.

- -

- Fold and unfold: Specific to the winter cover system, this refers to folding and unfolding the cover when wind speed exceeds a critical threshold, risking damage to the cover and vine plants. It only covers the transportation of human labor from the farm to the vine plot.

2.5. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Direct Emission Models

- -

- Phosphorus emissions are estimated based on fertilizer application and soil content using the SALCA-P model [35].

- -

- -

- On-field pesticide active ingredients emissions are calculated with the Pest-LCI model [39]. This model accounts for the type of sprayer, the development stage of the vine canopy, and the width of the non-treated zone.

- -

- On-field heavy metal emissions of cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, lead, zinc, and mercury resulting from fertilizer applications and atmospheric deposition are calculated with the SALCA heavy metals method [40].

- -

- On-field CO2 emissions from lime, dolomite, and urea applications are calculated based on the emission factors of the IPCC chapter 11 volume 4 [36].

- -

- On-field combustion emissions are calculated with the Ecoinvent model from Nemecek and Kägi [41].

2.6. LCA Software and Databases

2.7. Global Environmental Assessment Approach

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Shares of the PTO Without ASFPM

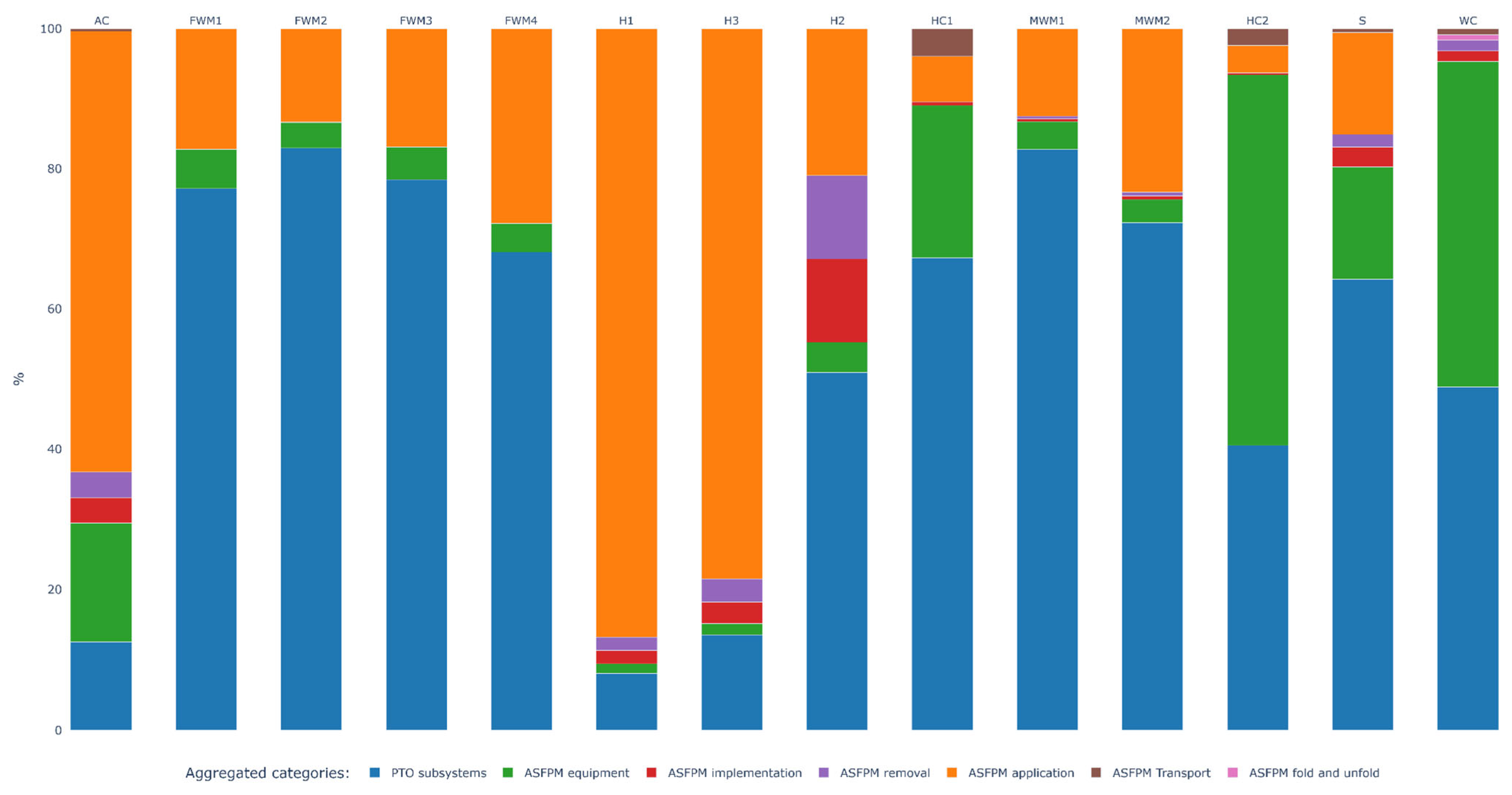

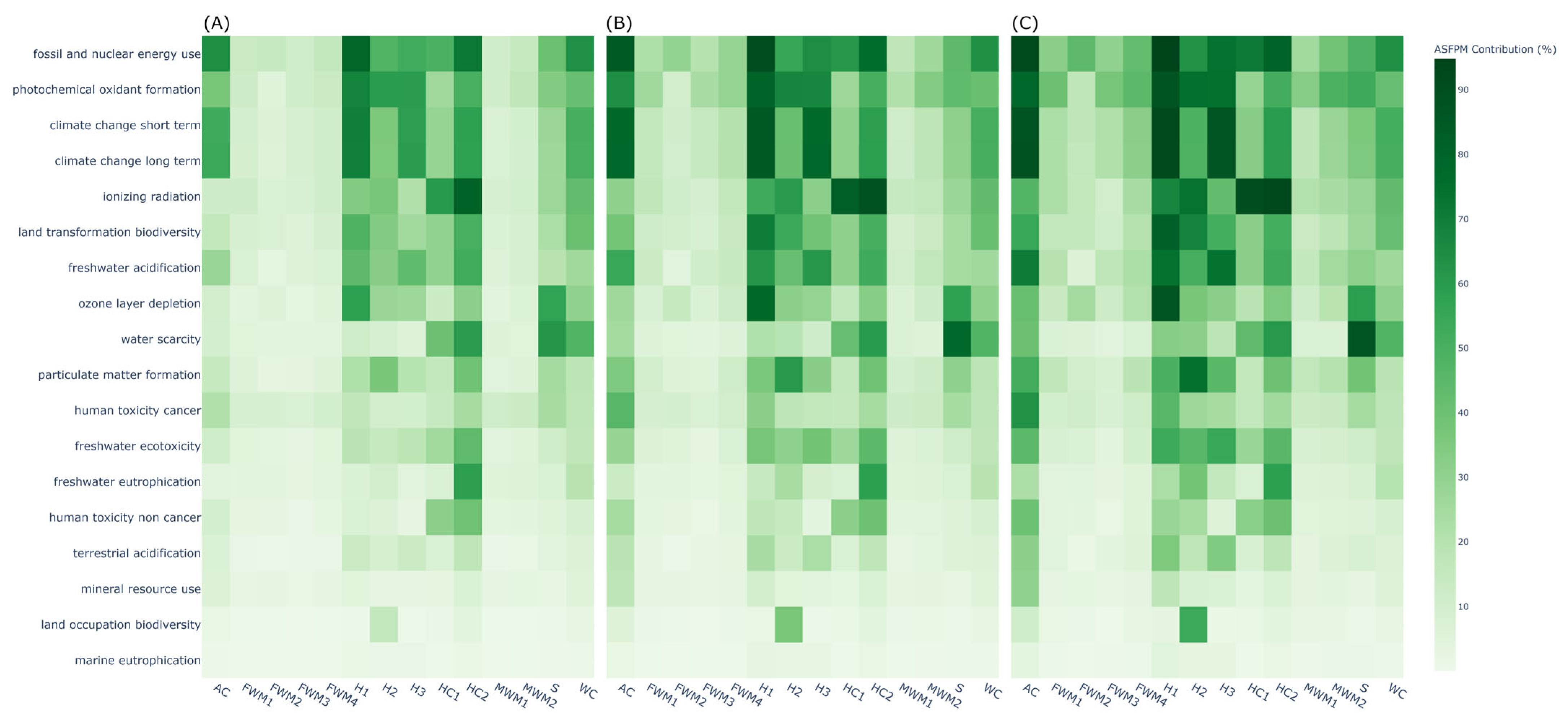

3.2. Environmental Shares of ASFPM into the PTO

3.3. Uncertainties Analysis of PTO with ASFPM Application

- -

- Water scarcity: 4371 m3 world eq.

- -

- Human toxicity (non-cancer): 3501 CTUh.

- -

- Homan toxicity (cancer): 535 CTUh.

- -

- Ionizing radiation: 72 Bq C-14 eq.

- -

- Land transformation biodiversity: 60 m2yr arable.

- -

- Marine eutrophication: 0.48 kg N eq.

- -

- Land occupation biodiversity: 2.15 m2yr arable.

- -

- Climate change: 3.81 kg CO2 eq.

- -

- Terrestrial acidification: 4.27 kg SO2 eq.

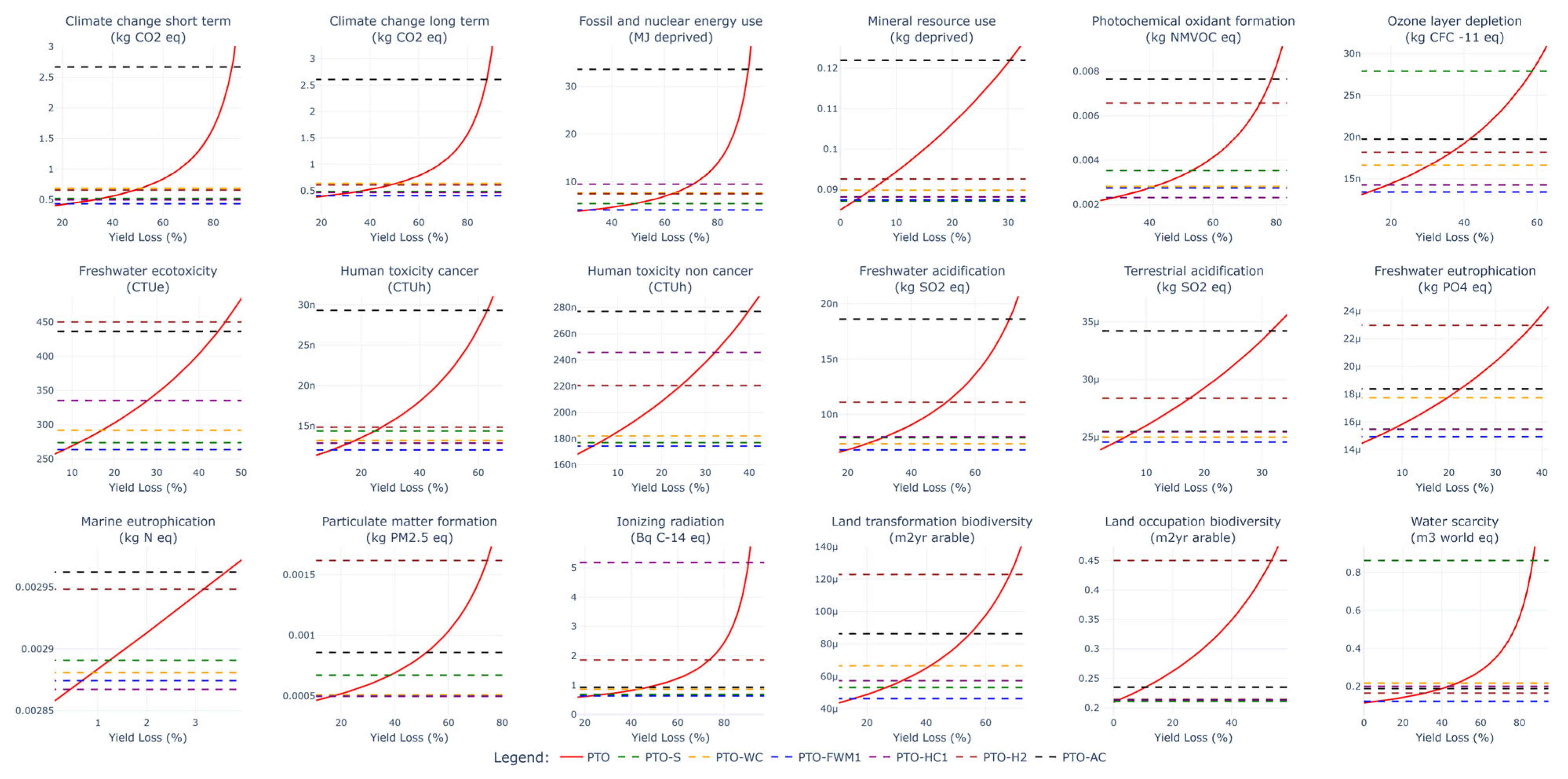

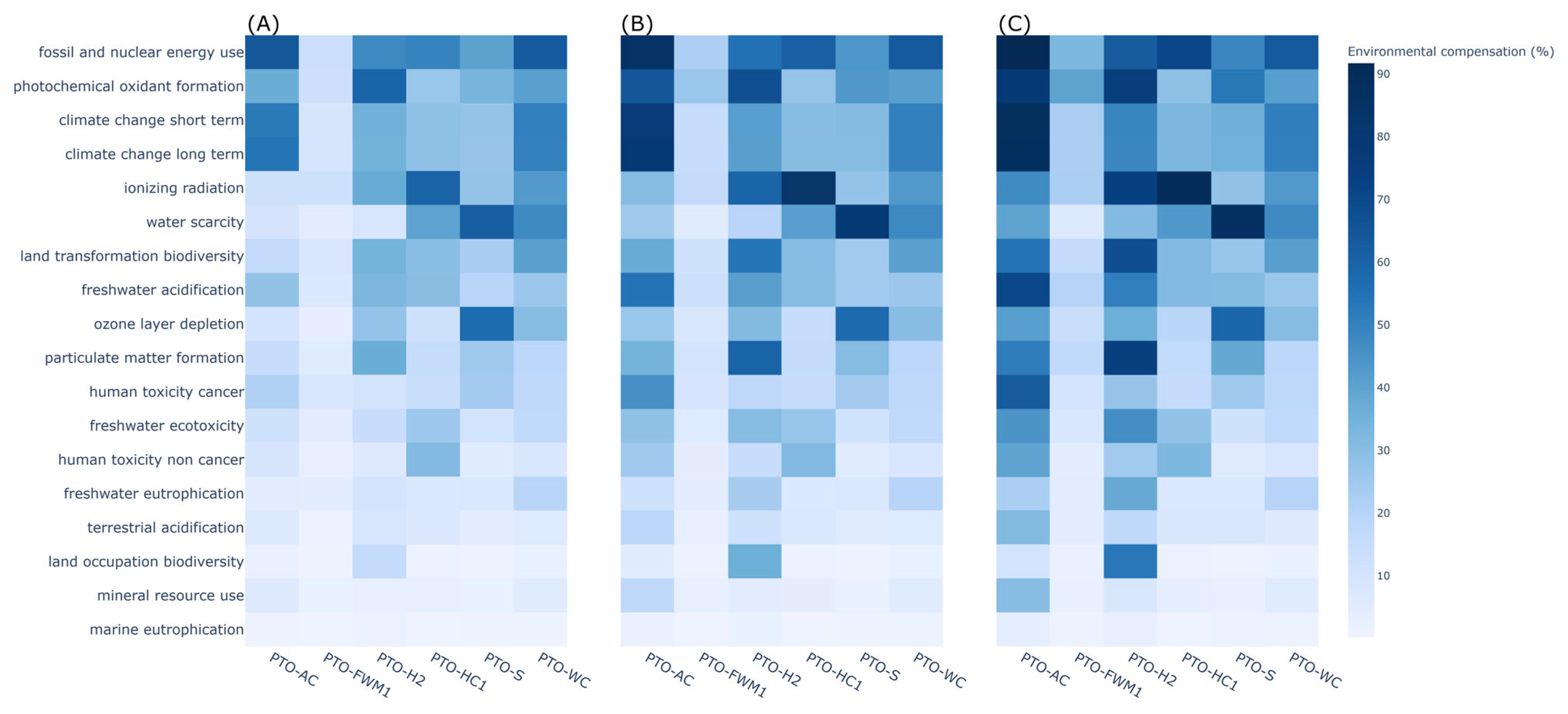

3.4. Environmental Offset of ASFPM Use into a PTO with Potential Yield Loss

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katherine, C.; Dipak, D.; Gerhard, K.; Aditi, M.; Peter, W.T.; Christopher, T.; José, R.; Paulina, A.; Ko, B.; Gabriel, B.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Leolini, L.; Moriondo, M.; Fila, G.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; Ferrise, R.; Bindi, M. Late spring frost impacts on future grapevine distribution in Europe. Field Crops Res. 2018, 222, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartschall, T.; Wodinski, M.; Von Bloh, W.; Oesterle, H.; Rachimow, C.; Hoppmann, D. Changes in phenology and frost risks of Vitis vinifera (cv Riesling). Meteorol. Z. 2015, 24, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosedale, J.R.; Wilson, R.J.; Maclean, I.M.D. Climate Change and Crop Exposure to Adverse Weather: Changes to Frost Risk and Grapevine Flowering Conditions. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethling, E.; Petitjean, T.; Quénol, H.; Barbeau, G. Assessing local climate vulnerability and winegrowers’ adaptive processes in the context of climate change. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2017, 22, 777–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, S.; Pergaud, J.; Richard, Y.; Castel, T.; Le Roux, R.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Quenol, H.; Bois, B. Projected impacts of climate change on viticulture over French wine regions using downscaled CMIP6 multi-model data. OENO One 2023, 57, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitjean, T.; Tissot, C.; Thibault, J.; Rouan, M.; Quenol, H.; Bonnardot, V. Évaluation spatio-temporelle de l’exposition au gel en régions viticoles traditionnelle (Pays de Loire) et émergente (Bretagne). In Proceedings of the 35ème Colloque de L’Association Internationale de Climatologie, Toulouse, France, 6–9 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sgubin, G.; Swingedouw, D.; Dayon, G.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Ollat, N.; Pagé, C.; van Leeuwen, C. The risk of tardive frost damage in French vineyards in a changing climate. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 250–251, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, C.; Zito, S.; Richard, Y.; Castel, T.; Morvan, G.; Bois, B. Frost risk projections in a changing climate are highly sensitive in time and space to frost modelling approaches. In Proceedings of the 14th International Terroir Congress & 2nd ClimWine Symposium, Bordeaux, France, 3–8 July 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J.A. An overview of climate change impacts on European viticulture. Food Energy Secur. 2012, 1, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droulia, F.; Charalampopoulos, I. Future Climate Change Impacts on European Viticulture: A Review on Recent Scientific Advances. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochard, J.; Monamy, C.; Pauthier, B.; Rocque, A. Stratégie et équipements de prévention vis-à-vis du gel de printemps et de la grêle. Perspectives en lien avec les changements climatiques, projet ADVICLIM. BIO Web Conf. 2019, 12, 01012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sherif, S.M. Combating Spring Frost With Ethylene. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillet, V.; Payen, A.; Naviaux, P.; Pauthier, B.; Chassaing, T.; Renaud-Gentié, C. Life Cycle Inventories and Unit Processes of Active Spring Frost Protection Methods Applied in Loire Valley and Champagne Regions. 2024. Available online: https://entrepot.recherche.data.gouv.fr/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.57745/RLG4DS (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Jolliet, O.; Saadé, M.; Crettaz, P.; Shaked, S. Analyse du Cycle de Vie: Comprendre et Réaliser un Écobilan; PPUR Presses Polytechniques: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 23, p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- Alhashim, R.; Deepa, R.; Anandhi, A. Environmental Impact Assessment of Agricultural Production Using LCA: A Review. Climate 2021, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; De Feo, G. Life Cycle Assessment Application to the Wine Sector: A Critical Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, F.C.; Döring, J.; Koch, M.; Kauer, R.; Stoll, M.; Wohlfahrt, Y.; Wagner, M. Comparative life cycle assessment of integrated and organic viticulture based on a long-term field trial in Germany. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud-Gentié, C.; Dieu, V.; Thiollet-Scholtus, M.; van der Werf, H.M.G.; Perrin, A.; Mérot, A. L’Analyse du Cycle de Vie pour réduire l’impact environnemental de la viticulture biologique. BIO Web Conf. 2019, 15, 01031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beauchet, S.; Rouault, A.; Renouf, M.A.; Thiollet-Scholtus, M.; Jourjon, F.; Renaud-Gentié, C. Inter-annual variability in the environmental performance of viticultural technical management routes–a case study in the Middle Loire Valley (France). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, B.; Dias, A.C.; Machado, M. Life cycle assessment of the supply chain of a Portuguese wine: From viticulture to distribution. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 18, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault, A.; Beauchet, S.; Renaud-Gentie, C.; Jourjon, F. Life Cycle Assessment of viticultural technical management routes (TMRs): Comparison between an organic and an integrated management route. OENO One 2016, 50, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. Analysis of sustainability based on Life Cycle Assessment: An empirical study of wine production. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2012, 1, 682–689. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud-Gentié, C.; Grémy-Gros, C.; Julien, S.; Giudicelli, A. Participatory ecodesign of crop management based on Life Cycle Assessment: An approach to inform the strategy of a Protected Denomination of Origin. A case study in viticulture. Ital. J. Agron. 2024, 18, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agraso-Otero, A.; Cancela, J.J.; Vilanova, M.; Ugarte Andreva, J.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; González-García, S. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability of Organic Wine Grape Production with Qualified Designation of Origin in La Rioja, Spain. Agriculture 2025, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud-Gentié, C.; Dijkman, T.J.; Anders, B.; Morten, B. Modeling pesticides emissions for Grapevine Life Cycle Assessment: Adaptation of Pest-LCI model to viticulture. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on LCA of Food, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–11 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baillet, V.; Symoneaux, R.; Renaud-Gentié, C. Life cycle assessment of active spring frost protection methods in viticulture: A framework to compare different technologies. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 14, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milà i Canals, L.; Burnip, G.M.; Cowell, S.J. Evaluation of the environmental impacts of apple production using Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Case study in New Zealand. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 114, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiollet-Scholtus, M.; Bockstaller, C. Using indicators to assess the environmental impacts of wine growing activity: The INDIGO® method. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 62, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillet, V.; Pauthier, B.; Payen, A.; Naviaux, P.; Symoneaux, R.; Chassaing, T.; Renaud-Gentié, C. Life cycle assessment of active spring frost protection methods in viticulture in the Loire Valley and Champagne French regions. OENO One 2025, 59, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud-Gentié, C. Eco-Efficiency of Vineyard Technical Management Routes: Interests and Adaptations of Life Cycle Assessment to Account for Specificities of Quality Viticulture. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Angers, Angers, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le Cap, C. Numerical Simulations and Field Measurements of Frost Events in a Vineyard Equipped with Wind Machines: Application to the Quincy Vineyard. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Rennes, Rennes, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.G. The art of protecting grapevines from low temperature injury. In Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, WA, USA, 19–23 June 2000; pp. 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Poling, E.B. Spring Cold Injury to Winegrapes and Protection Strategies and Methods. HortScience 2008, 43, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasuhn, V. Erfassung der PO4-Austräge für die Ökobilanzierung SALCA Phosphor; Agroscope-Reckenholz-Tänikon Research Station ART: Zürich, Switzerland, 2006; 20p. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Chapter 11: N2O Emissions from Managed Soils, and CO2 Emissions from Lime and Urea Application; IPCC: Paris, France, 2006; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Brentrup, F.; Küsters, J.; Lammel, J.; Kuhlmann, H. Methods to estimate on-field nitrogen emissions from crop production as an input to LCA studies in the agricultural sector. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2000, 5, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemecek, T.; Schnetzer, J. Methods of Assessment of Direct Field Emissions for LCIs of Agricultural Production Systems, Data v3.0 (2012); Agroscope Reckenholz-Tanïkon Research Station ART: Zurick, Switzerland, 2011; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek, T.; Antón, A.; Basset-Mens, C.; Gentil-Sergent, C.; Renaud-Gentié, C.; Melero, C.; Naviaux, P.; Peña, N.; Roux, P.; Fantke, P. Operationalising emission and toxicity modelling of pesticides in LCA: The OLCA-Pest project contribution. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiermuth, R. Modell zur Berechnung der Schwermetallflüsse in der Landwirtschaftlichen Ökobilanz–SALCA-Schwermetall; Forschungsanstalt Agroscope Reckenholz-Tänikon (ART): Zürich, Switzerland, 2006; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek, T.; Kägi, T. Life Cycle Inventories of Swiss and European Agricultural Production Systems; Agroscope Reckenholz-Taenikon Research Station ART: Zurich and Dübendorf, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 1–360. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud-Gentié, C.; Burgos, S.; Benoît, M. Choosing the most representative technical management routes within diverse management practices: Application to vineyards in the Loire Valley for environmental and quality assessment. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 56, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TechniLoire. Equipements de Protection Face au Gel; InterLoire: Tours, France, 2023; 25p. [Google Scholar]

- Viveros Santos, I.; Renaud-Gentié, C.; Roux, P.; Levasseur, A.; Bulle, C.; Deschênes, L.; Boulay, A.-M. Prospective life cycle assessment of viticulture under climate change scenarios, application on two case studies in France. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drepper, B.; Bamps, B.; Gobin, A.; Van Orshoven, J. Strategies for managing spring frost risks in orchards: Effectiveness and conditionality—A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 2022, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, L.; Brotodjojo, R.R.R. Frost Protection Case Study in Orchards. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1018, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battany, M.C. Vineyard frost protection with upward-blowing wind machines. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 157, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo-Abreu, J.P.; Villalobos, F.J.; Mateos, L. Frost Protection. In Principles of Agronomy for Sustainable Agriculture; Villalobos, F.J., Fereres, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, R.; Tillman, A.M.; Sandén, B.A.; Janssen, M.; Nordelöf, A.; Kushnir, D.; Molander, S. Environmental assessment of emerging technologies: Recommendations for prospective LCA. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Benini, L.; Crenna, E.; Secchi, M. Global Environmental IMPACTS and Planetary Boundaries in LCA; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016.

- Ryberg, M.W.; Owsianiak, M.; Richardson, K.; Hauschild, M.Z. Challenges in implementing a Planetary Boundaries based Life-Cycle Impact Assessment methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bare, J.C.; Hofstetter, P.; Pennington, D.W.; de Haes, H.A.U. Midpoints versus endpoints: The sacrifices and benefits. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2000, 5, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kägi, T.; Dinkel, F.; Frischknecht, R.; Humbert, S.; Lindberg, J.; De Mester, S.; Ponsioen, T.; Sala, S.; Schenker, U.W. Session “Midpoint, endpoint or single score for decision-making?”—SETAC Europe 25th Annual Meeting, May 5th, 2015. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Label | Type of ASFPM | Highlighted Detail |

|---|---|---|

| PTO | Pathway of technical operations | All technical operations applied during the annual production |

| AC | Antifrost candles | Petrol as a raw material |

| FWM1 | Wind machine | Fixed machine, diesel fuel, with small heaters |

| FWM2 | Wind machine | Fixed, gas fuel, with small heaters |

| FWM3 | Wind machine | Fixed, diesel fuel, without small heaters |

| FWM4 | Wind machine | Fixed, diesel fuel, with burner |

| H1 | Heater | Use fuel as an energy resource |

| H2 | Heater | Use wood as an energy resource |

| H3 | Heater | Use peat as an energy resource |

| HC1 | Heating cable | Electric heating with copper cable |

| HC2 | Heating cable | Radiative cable with light-emitting diode |

| MWM1 | Wind machine | Mobile, diesel fuel, with a small heater and generator |

| MWM2 | Wind machine | Mobile, diesel fuel, with a small heater |

| S | Sprinkler | 35 m3 of direct water consumption |

| WC | Winter cover | Non-woven polypropylene cover |

| System Assessed | Context | Functional Unit | Chart |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTO without ASFPM | NR | To conduct 1 ha of vineyard over one year of production | Barplot of environmental share of all PTO subsystems (Figure 1) |

| ASFPM within a PTO | 11 h frost/year | Barplot of environmental share of ASFPM subsystems (climate change short-term indicator) (Figure 2) | |

| ASFPM within a PTO | 11 h frost/year | Heatmaps of environmental share o for all indicators (Figure 3A–C) | |

| 5 h frost/year | |||

| 1 h frost/year | |||

| PTO with ASFPM | 11 h frost/year | To produce 1 kg of grapes | Environmental impacts per kg of grapes produced (Figure 4) |

| PTO without ASFPM | yield loss range from 0 to 100% | Environmental impacts per kg of grapes produced depending on yield loss in % (Figure 4) | |

| PTO with ASFPM | 11 h frost/year | Heatmaps of the environmental compensation for all indicators (Figure 5A–C) | |

| 5 h frost/year | |||

| 1 h frost/year |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baillet, V.; Symoneaux, R.; Renaud-Gentié, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Spring Frost Protection Methods: High and Contrasted Environmental Consequences in Vineyard Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177835

Baillet V, Symoneaux R, Renaud-Gentié C. Life Cycle Assessment of Spring Frost Protection Methods: High and Contrasted Environmental Consequences in Vineyard Management. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177835

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaillet, Vincent, Ronan Symoneaux, and Christel Renaud-Gentié. 2025. "Life Cycle Assessment of Spring Frost Protection Methods: High and Contrasted Environmental Consequences in Vineyard Management" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177835

APA StyleBaillet, V., Symoneaux, R., & Renaud-Gentié, C. (2025). Life Cycle Assessment of Spring Frost Protection Methods: High and Contrasted Environmental Consequences in Vineyard Management. Sustainability, 17(17), 7835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177835