Sustainability for Predicting Customer Lifetime Value: A Mediation–Moderation Effect Across SEO Metrics in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theorical Background

2.1. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and Source Credibility Theory

2.2. Sustainability and Marketing Outcomes Based on Customers

2.3. Woozle Effect in the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM)

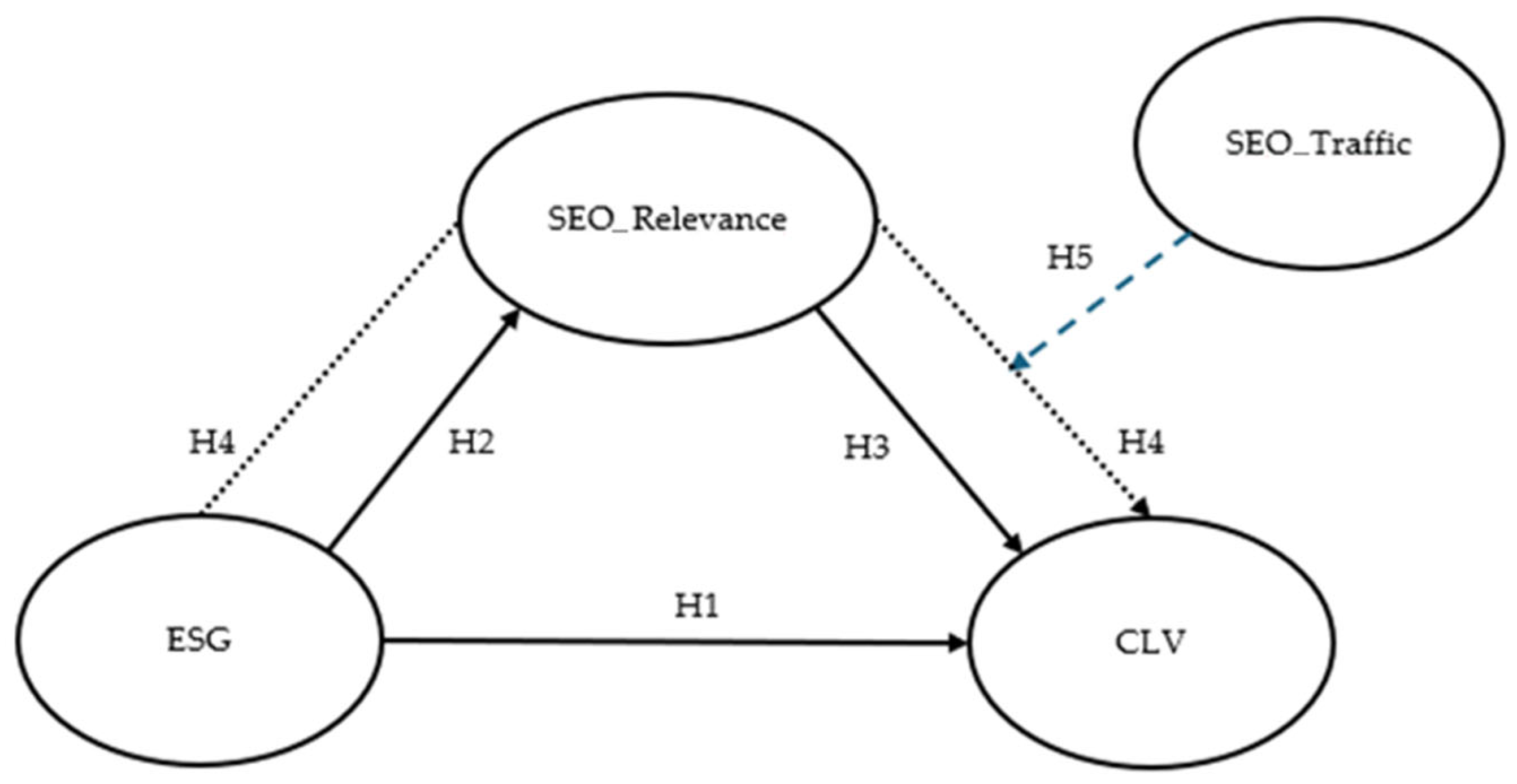

2.4. Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Confetto, M.G.; Covucci, C. “Sustainability-Contents SEO”: A Semantic Algorithm to Improve the Quality Rating of Sustainability Web Contents. TQM J. 2021, 33, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkasi, N.; Agag, G. How Does Risk Interplay with Trust in Pre-and Post-Purchase Intention to Engage: PLS-SEM and ML Classification Approach. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozáková, J.; Urbánová, M.; Skypalova, R. Differences in Corporate Social Responsibility Implementation between Slovak and Czech Companies. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2024, 22, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehl, S.; Friedman, B.A. Consumer Perceived Authenticity of Organizational Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Statements: A Test of Attribution Theory. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M. Consumer Formation of CSR Image: Role of Altruistic Values. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, A.A.; Liu, H. Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Authenticity in Developing Perceived Brand Loyalty: A Consumer Perceptions Paradigm. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Jha, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in Marketing: A Review of the State-of-the-Art Literature. J. Soc. Mark. 2019, 9, 418–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominique-Ferreira, S.; Rodrigues, B.Q.; Braga, R.J. Personal Marketing and the Recruitment and Selection Process: Hiring Attributes and Particularities in Tourism and Hospitality. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2022, 32, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolkov, I.; Karyy, O.; Skybinskyi, O.; Ugolkova, O.; Zhezhukha, V. The Evaluation of Content Effectiveness within Online and Offline Marketing Communications of an Enterprise. Innov. Mark. 2020, 16, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakas, D.P.; Reklitis, D.P.; Giannakopoulos, N.T.; Trivellas, P. The Influence of Websites User Engagement on the Development of Digital Competitive Advantage and Digital Brand Name in Logistics Startups. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 29, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwanji, V.S.; Lee, J.; Cortese, J. Future-Proofing Search Engine Marketing: An Empirical Investigation of Effects of Search Engine Results on Consumer Purchase Decisions. J. Strateg. Mark. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U. The Impact of Source Credible Online Reviews on Purchase Intention: The Mediating Roles of Brand Equity Dimensions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google User Content. General Guidelines. Available online: https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/guidelines.raterhub.com/en//searchqualityevaluatorguidelines.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D.; Nasiopoulos, D.K. Airlines’ Sustainability Study Based on Search Engine Optimization Techniques and Technologies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confetto, M.G.; Covucci, C. A Taxonomy of Sustainability Topics: A Guide to Set the Corporate Sustainability Content on the Web. TQM J. 2021, 33, 106–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Lee, N.; Roemer, E.; Kemény, I.; Dirsehan, T.; Cadogan, J.W. Beware of the Woozle Effect and Belief Perseverance in the PLS-SEM Literature! Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 715–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, F.; Hubona, G.; Roemer, E.; Zaza, S.; Schamberger, T.; Chuah, F.; Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Henseler, J. The Choice of Structural Equation Modeling Technique Matters: A Commentary on Dash and Paul (2021). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Schuberth, F.; Lee, N.; Kemény, I. Why Researchers Should Be Cautious about Using PLS-SEM. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2025, 128, A8–A15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakas, D.P.; Giannakopoulos, N.T.; Nasiopoulos, D.K.; Kanellos, N.; Tsoulfas, G.T. Assessing the Efficacy of Cryptocurrency Applications’ Affiliate Marketing Process on Supply Chain Firms’ Website Visibility. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, N.; Karountzos, P.; Giannakopoulos, N.T.; Terzi, M.C.; Sakas, D.P. Digital Marketing Strategies and Profitability in the Agri-Food Industry: Resource Efficiency and Value Chains. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallez, M.; Lopezosa, C.; Pedraza-Jiménez, R. A Study of the Web Visibility of the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda on University Websites. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Keywords: SEO for Beginners. Available online: https://www.semrush.com/blog/organic-keywords/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Mozscape API. Available online: https://moz.com/products/api (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, M.; Pizzi, G.; Pichierri, M. Fake News, Real Problems for Brands: The Impact of Content Truthfulness and Source Credibility on Consumers’ Behavioral Intentions toward the Advertised Brands. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, P.R.; Melancon, J. Gender and Live-Streaming: Source Credibility and Motivation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaput, M. What is Google BERT? Available online: https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/blog/bert-google (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Kapoor, P.S.; Balaji, M.S.; Jiang, Y. Greenfluencers as Agents of Social Change: The Effectiveness of Sponsored Messages in Driving Sustainable Consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 533–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.-C.; Sinha, J. How Social Media Usage and the Fear of Missing out Impact Minimalistic Consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 1083–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Mohamad Saleh, M.S.; Zolkepli, I.A. The Moderating Effect of Green Advertising on the Relationship between Gamification and Sustainable Consumption Behavior: A Case Study of the Ant Forest Social Media App. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social Media: The New Hybrid Element of the Promotion Mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Witmaier, A.; Ko, E. Sustainability and Social Media Communication: How Consumers Respond to Marketing Efforts of Luxury and Non-Luxury Fashion Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, K.W. Influencing Factors of Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention to Sustainable Apparel Products: Exploring Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Risselada, H.; Verhoef, P.C. Does Sustainability Sell? The Impact of Sustainability Claims on the Success of National Brands’ New Product Introductions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannopoulou, N.; Chandrasapth, K.; Bian, X.; Jin, B.; Gupta, S.; Liu, M.J. How Disinformation Affects Sales: Examining the Advertising Campaign of a Socially Responsible Brand. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder Legitimacy in Firm Greening and Financial Performance: What about Greenwashing Temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimonenko, T.; Bilan, Y.; Horák, J.; Starchenko, L.; Gajda, W. Green Brand of Companies and Greenwashing under Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Chishti, M.F.; Durrani, M.K.; Bashir, R.; Safdar, S.; Hussain, R.T. The Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Impact on Financial Performance: A Case of Developing Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra-Moliner, J.R.; Bel-Oms, I. How Does Each ESG Dimension Predict Customer Lifetime Value by Segments? Evidence from U.S. Industrial and Technological Industries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Meneses, G.; Amador-Marrero, M.; Spinelli Guedes, C. The Criteria of Inbound Marketing to Segment and Explain the Domain Authority of the Cellars’ E-Commerce in the Canary Islands. Systems 2023, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, D.; Jaheer Mukthar, K.P.; Zarzosa-Marquez, E.; Pérez Falcón, J.; Jamanca-Anaya, R.; Silva-Gonzales, L. Impact of Digital Marketing and IoT Tools on MSME’s Sales Performance and Business Sustainability. In Technological Sustainability and Business Competitive Advantage; Al Mubarak, M., Hamdan, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 65–77. ISBN 9783031355240. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinitiv. Environmental, Social and Governance Scores from Refinitiv. May. Available online: https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/refinitiv-esg-scores-methodology.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Sparacino, A.; Merlino, V.M.; Borra, D.; Massaglia, S.; Blanc, S. Web Content Analysis of Beekeeping Website Companies: Communication and Marketing Strategies in the Italian Context. J. Mark. Commun. 2024, 30, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Vela, E.G.; Li, W.; Dakhan, S.A.; Hong Thuy, T.T.; Merani, S.H. Effects of Perceived Service Quality, Website Quality, and Reputation on Purchase Intention: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Trust and Perceived Risk in Online Shopping. Cogent. Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1869363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.J.D.V.T.; Hernández-Maestro, R.M.; Muñoz-Gallego, P.A. Service Quality Perceptions, Online Visibility, and Business Performance in Rural Lodging Establishments. J. Travel. Res. 2017, 56, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baye, M.R.; De Los Santos, B.; Wildenbeest, M.R. Search Engine Optimization: What Drives Organic Traffic to Retail Sites? Econ. Manag. Strategy 2016, 25, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, D.; Rajapakse, A.; Kožuljević, N.; Shukla, Y. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) for Digital Marketers: Exploring Determinants of Online Search Visibility for Blood Bank Service. Online Inf. Rev. 2023, 47, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 5, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormann, T.; Möller, F.; Hoppe, C.; vom Brocke, J. Digital Sustainability. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Mean | St | Min | Max | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 41.8 | 21.6 | 1 | 95 | 296 |

| Governance | 50.2 | 23.1 | 3 | 95 | 296 |

| Social | 52.2 | 21.6 | 2 | 95 | 296 |

| ln_CLV profit-margin infinite | 13.2 | 2.2 | 3 | 19 | 296 |

| ln_CLV sales infinite | 15.7 | 1.8 | 11 | 21 | 296 |

| Ahref domain rating (DR) | 61.2 | 16.5 | 7 | 95 | 296 |

| Moz domain authority (DA) | 49.3 | 16.1 | 18 | 95 | 296 |

| porce_organic | 41.7 | 15.9 | 2 | 79 | 296 |

| porce_organic_nobranded | 24.2 | 14.1 | 0 | 68 | 296 |

| Indicator → Composite | Loads | 5.0% | 95.0% | Weights | 5.0% | 95.0% | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental → ESG | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.50 | 1.80 |

| Governance → ESG | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 1.25 |

| Social → ESG | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 1.78 |

| ahref_domain rating (DR) → SEO_R | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 3.21 |

| ln_CLV_profit margin_infinite → CLV | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 3.45 |

| ln_CLV sales infinite → CLV | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 3.45 |

| moz_domain authority (DA) → SEO_R | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.99 | 3.21 |

| porce_organic → SEO_T | 0.99 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 1.35 |

| porce_organic_nobranded → SEO_T | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 1.35 |

| Path | Beta | 2.5% | 97.5% | Fulfilment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG → CLV (direct effect) | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.62 | H1 Accepted |

| ESG → WEB (direct effect) | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.58 | H2 Accepted |

| SEO_R → CLV (direct effect) | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.37 | H3 Accepted |

| ESG → SEO_R → CLV (indirect effect) | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.19 | H4 Accepted |

| (ESG → SEO_R) x (SEO x SEO_R → CLV) (mediation moderation effect) | - | −0086 | −0001 | H5 Accepted |

| Composite | q2_Predict | R-Square | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLV | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.04 |

| SEO_R | 0.22 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Segarra-Moliner, J.R. Sustainability for Predicting Customer Lifetime Value: A Mediation–Moderation Effect Across SEO Metrics in Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177829

Segarra-Moliner JR. Sustainability for Predicting Customer Lifetime Value: A Mediation–Moderation Effect Across SEO Metrics in Europe. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177829

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegarra-Moliner, José Ramón. 2025. "Sustainability for Predicting Customer Lifetime Value: A Mediation–Moderation Effect Across SEO Metrics in Europe" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177829

APA StyleSegarra-Moliner, J. R. (2025). Sustainability for Predicting Customer Lifetime Value: A Mediation–Moderation Effect Across SEO Metrics in Europe. Sustainability, 17(17), 7829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177829