The Impact of Greenwashing Awareness and Green Perceived Benefits on Green Purchase Propensity: The Mediating Role of Green Consumer Confusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Institutional Framework in Greece and the EU

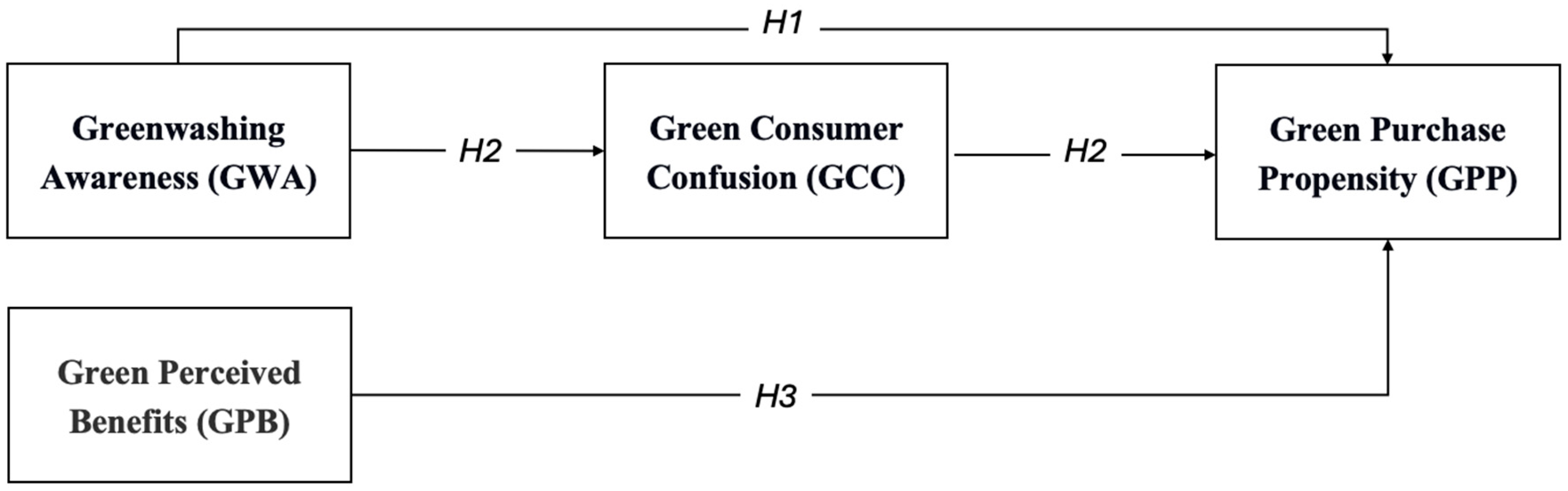

4. Theoretical Background

5. Hypotheses Development

6. Methodology

- Are you the family member who does the grocery shopping?

- Do you go to the supermarket to do your shopping?

7. Findings

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Greenwashing Awareness (GWA) | GWA1: It is difficult to identify whether a product is misleading about its environmental characteristics through the use of text. (R) | Adapted from [52] |

| GWA2: It is difficult to identify if a product is misleading about its environmental characteristics through the use of images and graphics. (R) | ||

| GWA3: It is difficult to determine whether a product has an unclear or unproven environmental/green claim. (R) | ||

| GWA4: It is difficult to perceive if a product exaggerates its “green” attributes. (R) | ||

| GWA5: It is difficult to recognize when a product omits important information to make it appear “greener” than it actually is. (R) | ||

| Green Perceived Benefits (GPB) | GPB1: Green products have more advantages than conventional products. | Adapted from [86] |

| GPB2: The consumption of green products ensures a better quality of life. | ||

| GPB3: The consumption of green products improves my health. | ||

| GPB4: The consumption of green products meets my expectations. | ||

| Green Consumer Confusion (GCC) | GCC1: There are a lot of similarities between many products, making it difficult to know which ones are really green. | Adapted from [52] |

| GCC2: The difference between a green product and a non-green product is difficult to discern. | ||

| GCC3: With so many products on the market, it can be confusing to identify their green features. | ||

| GCC4: Choosing a product that is made with respect for the environment is difficult because there are so many to choose from. | ||

| GCC5: I feel inadequately informed about whether a product is green or not every time I buy it. | ||

| GCC6: Every time I buy a product, I am not sure about its environmental characteristics. | ||

| Green Purchase Propensity (GPP) | GPP1: I buy a product because the company that makes it is more environmental responsible than its competitors. | Adapted from Chen and Chang [89] |

| GPP2: I buy a product because it is green. | ||

| GPP3: I buy a product because it has more green benefits than other products. |

References

- Varah, F.; Mahongnao, M.; Pani, B.; Khamrang, S. Exploring young consumers’ intention toward green products: Applying an extended theory of planned behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 9181–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Wong, I.A. Green marketing programs as strategic initiatives in hospitality. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.C. Green marketing orientation: Achieving sustainable development in green hotel management. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.M.F.; Reis, R. Factors affecting skepticism toward green advertising. In Green Advertising and the Reluctant Consumer; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Do Paço, A.; Shiel, C.; Alves, H. A new model for testing green consumer behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.C.; Chebeň, J.; Lančarič, D. Cross-cultural investigation of consumers’ generations attitudes towards purchase of environmentally friendly products in apparel retail. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2017, 12, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liargovas, P.; Apostolopoulos, N.; Pappas, I.; Kakouris, A. SMEs and green growth: The effectiveness of support mechanisms and initiatives matters. In Green Economy in the Western Balkans: Towards a Sustainable Future; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; pp. 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Han, H. Intention to pay conventional-hotel prices at a green hotel—A modification of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydock III, S.; Pervan, S.J.; Almubarak, A.F.; Johnson, L.; Kortt, M. Influence of made with renewable energy appeal on consumer behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pandey, M. Social media and impact of altruistic motivation, egoistic motivation, subjective norms, and ewom toward green consumption behavior: An empirical investigation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Nogueira, S. Willingness to pay more for green products: A critical challenge for Gen Z. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, G.; Secer, A.; Ghazalian, P.L. What Factors Influence Consumers to Buy Green Products? An Analysis through the Motivation–Opportunity–Ability Framework and Consumer Awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M.; Piha, L. The interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.; Walmsley, A.; Apostolopoulos, N. The mindset of eco and social entrepreneurs: Piloting a new measure of ‘sustainability mindset’. In ECIE 2019 14th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (2 Vols); Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited: Reading, UK, 2019; p. 686. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, M. The effect of greenwashing information on ad evaluation. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Pacheco, O.E.; Claasen, C. Fuzzy reporting as a way for a company to greenwash: Perspectives from the Colombian reality. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2017, 15, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri Cornish, L.; Moraes, C. The impact of consumer confusion on nutrition literacy and subsequent dietary behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.P.; Chang, S.C.; Liang, T.C.; Situmorang, R.O.P.; Hussain, M. Consumer confusion and green consumption intentions from the perspective of food-related lifestyles on organic infant milk formulas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Mitchell, V.W. The effect of consumer confusion proneness on word of mouth, trust, and customer satisfaction. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 838–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previte, J.; Drennan, J.; Sullivan Mort, G. M-technology, consumption and gambling: A conceptualisation of consumer vulnerability in an m-gambling marketplace. In Macromarketing 2006 Seminar Proceedings: Macromarketing the Future of Marketing? Marketing Department, University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 2006; pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Why not green marketing? Determinants of consumers’ intention to green purchase decision in a new developing nation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.P.; Cremasco, C.P.; Gabriel Filho, L.R.A.; Junior, S.S.B.; Bednaski, A.V.; Quevedo-Silva, F.; Padgett, R.C.M.L. Fuzzy inference system to study the behavior of the green consumer facing the perception of greenwashing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 116064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Wang, P.; Kuah, A.T. Why wouldn’t green appeal drive purchase intention? Moderation effects of consumption values in the UK and China. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Zabin, I. Consumer’s attitude towards purchasing green food. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mukonza, C.; Swarts, I. The influence of green marketing strategies on business performance and corporate image in the retail sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzi, G.; Murino, T.; Romano, E. An innovative approach to environmental issues: The growth of a green market modeled by system dynamics. In New Trends in Software Methodologies, Tools and Techniques; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 538–557. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.H.; Villegas, J. Consumer responses to advertising on the internet: The effect of individual difference on ambivalence and avoidance. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 10, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesprasit, K.; Aksharanandana, P.; Kanchanavibhu, A. Building green entrepreneurship: A journey of environmental awareness to green entrepreneurs in Thailand. J. Inf. Technol. Appl. Manag. 2020, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sawant, R. A study on awareness and demand pattern amongst consumers WRT green products. Int. J. Mark. Technol. 2015, 5, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Free, C.; Jones, S.; Tremblay, M.S. Greenwashing and sustainability assurance: A review and call for future research. J. Account. Lit. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Coelho, A.; Marques, A. A systematic literature review on greenwashing and its relationship to stakeholders: State of art and future research agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 74, 1397–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.D.L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Cao, T.T. Greenwashing behaviours: Causes, taxonomy and consequences based on a systematic literature review. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 21, 1486–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Seele, P.; Rademacher, L. Grey zone in–greenwash out. A review of greenwashing research and implications for the voluntary–mandatory transition of CSR. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Baumann, D. Global rules and private actors: Toward a new role of the transnational corporation in global governance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 16, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fairclough, S.; Dibrell, C. Attention, action, and greenwash in family-influenced firms? Evidence from polluting industries. Organ. Environ. 2017, 30, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, C.L.; Chang, C.H. The influence of greenwash on green word-of-mouth (green WOM): The mediation effects of green perceived quality and green satisfaction. Qual. Quant. 2014, 48, 2411–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, Q.; Dai, J.; Yang, B.; Li, L. Urban Residents’ Green Agro-Food Consumption: Perceived Risk, Decision Behaviors, and Policy Implications in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haba, H.F.; Bredillet, C.; Dastane, O. Green consumer research: Trends and way forward based on bibliometric analysis. Clean. Responsib. Consum. 2023, 8, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, N.U.; Mendoza, S.A.J.; Shamsuddinova, S. The Concept of Greenwashing and its Impact on Green Trust, Green Risk, and Green Consumer Confusion: A Review-Based Study. J. Asian Bus. Strategy 2022, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabieh, S.M.Z.A. The impact of greenwash practices over green purchase intention: The mediating effects of green confusion, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, S.A.; Azmoon, I.; Fekete-Farkas, M. The impact of perceived sustainable marketing policies on green customer satisfaction. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ji, R.; Park, S.D. Unpacking Green Consumer Behavior Among Chinese Consumers: Dual Role of Perceived Value and Greenwashing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A.; Silkoset, R. Sustainable development and greenwashing: How blockchain technology information can empower green consumers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 32, 3801–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Trancoso, T. The dark side of green marketing: How greenwashing affects circular consumption? Sustainability 2023, 15, 11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, M.; Ul Haque, A. Are you environmentally conscious enough to differentiate between greenwashed and sustainable items? A global consumers perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argiros, G. Consumer safety in Greece: An analysis of the Consumer Protection Act 1991. J. Consum. Policy 1994, 17, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douga, A.E.; Koumpli, V.P. Enforcement and Effectiveness of Consumer Law in Greece. In Enforcement and Effectiveness of Consumer Law; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 307–329. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Claims. 2023. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/green-claims_en (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Communication Control Board. Greek Advertising and Communication Code (Greek). 2023. Available online: https://www.see.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/EKDE_2023.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Changing behavior using the theory of planned behavior. In The Handbook of Behavior Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Waris, I.; Amin ul Haq, M. Predicting eco-conscious consumer behavior using theory of planned behavior in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 15535–15547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Vaccari, A.; Ferrari, E. Why eco-labels can be effective marketing tools: Evidence from a study on Italian consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, B.; Thejaswini, H.D. Consumers’ perception analysis-market awareness towards eco-friendly FMCG products: A case study of Mysore district. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friestad, M.; Wright, P. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, B.; Bijmolt, T.H.; Hoekstra, J.C. You don’t fool me! Consumer perceptions of digital native advertising and banner advertising. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2019, 16, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J. An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Newell, S.J. The dual credibility model: The influence of corporate and endorser credibility on attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2002, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Qiao, N.; Dabuo, F.T.; Zhu, C. The evolution mechanism of green products supply and demand in a demand-driven market. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, B. Impact of greenwashing perception on consumers’ green purchasing intentions: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Huang, A.F.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, Y.R. Greenwash and green purchase behaviour: The mediation of green brand image and green brand loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 31, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Pacheco, M. How green trust, consumer brand engagement and green word-of-mouth mediate purchasing intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ainn, Q.U.; Bashir, I.; Haq, J.U.; Bonn, M.A. Does Greenwashing Influence the Green Product Experience in Emerging Hospitality Markets Post-COVID-19? Sustainability 2022, 14, 12313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, D.; Awad, R. The Effect of Greenwashing on Consumers’ Green Purchase Intentions. Arab. J. Adm. 2024, 44, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, W. Consumer Confusion Proneness: Scale Development, Validation, and Application. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 697–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, S. Social Accountability and Corporate Greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjhin, V.U.; Abbas, B.S.; Budiastuti, D.; Kosala, R.; Lusa, S. The role of electronic word-of-mouth on customer confusion in increasing purchase intention. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2018, 26, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Morisada, M.; Miwa, Y.; Dahana, W.D. Identifying valuable customer segments in online fashion markets: An implication for customer tier programs. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 33, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, S.; Martínez, M.P.; Correa, C.M.; Moura-Leite, R.C.; Da Silva, D. Greenwashing effect, attitudes, and beliefs in green consumption. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Sharma, G. Relationship between the Constructs of Green Wash, Green Consumer Confusion, Green Perceived Risk and Green Trust Among Urban Consumers in India. Transnatl. Mark. J. 2021, 9, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray Shades of Green: Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. J. Bus. Ethic. 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Morwitz, V.G. Stated intentions and purchase behavior: A unified model. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoraki, K.K.; Deirmentzoglou, G.A.; Psychalis, M.; Apostolopoulos, S. Types of Innovation and Sustainable Development: Evidence from Medium-and Large-sized Firms. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2023, 21, 2450013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, M. Purposive sample. In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.B. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1991, 26, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions | Population | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Macedonia & Thrace | 562,069 | 17 |

| Central Macedonia | 1,792,069 | 50 |

| Western Macedonia | 255,056 | 7 |

| Epirus | 319,543 | 9 |

| Thessaly | 687,527 | 20 |

| Ionian Islands | 200,726 | 6 |

| Western Greece | 643,349 | 18 |

| Central Greece | 505,269 | 14 |

| Attica | 3,792,469 | 109 |

| Peloponnese | 583,366 | 17 |

| Northern Aegean | 194,136 | 6 |

| Southern Aegean | 324,542 | 9 |

| Crete | 617,360 | 18 |

| Variables | Items | FL | CR | AVE | a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWA | GWA1 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.91 |

| GWA2 | 0.88 | ||||

| GWA3 | 0.80 | ||||

| GWA4 | 0.81 | ||||

| GWA5 | 0.73 | ||||

| GPB | GPB1 | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.87 |

| GPB2 | 0.89 | ||||

| GPB3 | 0.84 | ||||

| GPB4 | 0.70 | ||||

| GCC | GCC1 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 0.9 |

| GCC2 | 0.82 | ||||

| GCC3 | 0.88 | ||||

| GCC4 | 0.83 | ||||

| GCC5 | 0.64 | ||||

| GCC6 | 0.73 | ||||

| GPP | GPP1 | 0.79 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.86 |

| GPP2 | 0.92 | ||||

| GPP3 | 0.94 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | GWA | GPB | GCC | GPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWA | 2.30 | 0.89 | (0.82) | |||

| GPB | 3.93 | 0.79 | −0.03 | (0.80) | ||

| GCC | 3.47 | 0.94 | −0.60 *** | −0.17 ** | (0.79) | |

| GPP | 3.54 | 0.95 | 0.14 * | 0.64 *** | −0.28 *** | (0.89) |

| Variables | GWA | GPB | GCC | GPP | Gender | Age | Education | Income | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWA | - | ||||||||

| GPB | −0.03 | - | |||||||

| GCC | −0.60 *** | −0.17 ** | - | ||||||

| GPP | 0.14 * | 0.64 *** | −0.28 *** | - | |||||

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | - | ||||

| Age | −0.15 ** | 0.07 | 0.17 ** | 0.10 | 0.00 | - | |||

| Education | 0.16 ** | 0.25 *** | −0.21 *** | 0.23 *** | −0.12 * | −0.12 * | - | ||

| Income | 0.29 *** | 0.11 | −0.25 *** | 0.15 ** | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.22 *** | - | |

| Location | −0.29 *** | −0.23 *** | 0.33 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.29 *** | −0.24 *** | - |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Purchase Propensity (GPP) | Green Consumer Confusion (GCC) | Green Purchase Propensity (GPP) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Control paths | ||||

| Education | 0.18 ** | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.06 |

| Income | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Location | −0.16 ** | −0.05 | 0.16 ** | −0.03 |

| Age | 0.09 | |||

| Direct effect paths | ||||

| GWA | 0.11 * | −0.52 *** | 0.04 | |

| GPB | 0.60 *** | 0.58 *** | ||

| Mediating path | ||||

| GCC | −0.12 * | |||

| Goodness-of-fit statistics | ||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| F | 10.76 | 42.99 | 42.58 | 36.87 |

| VIF | 1.10 | 1.16 | 1.13 | 1.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Apostolopoulos, N.; Makris, I.; Deirmentzoglou, G.A.; Apostolopoulos, S. The Impact of Greenwashing Awareness and Green Perceived Benefits on Green Purchase Propensity: The Mediating Role of Green Consumer Confusion. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146589

Apostolopoulos N, Makris I, Deirmentzoglou GA, Apostolopoulos S. The Impact of Greenwashing Awareness and Green Perceived Benefits on Green Purchase Propensity: The Mediating Role of Green Consumer Confusion. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146589

Chicago/Turabian StyleApostolopoulos, Nikolaos, Ilias Makris, Georgios A. Deirmentzoglou, and Sotiris Apostolopoulos. 2025. "The Impact of Greenwashing Awareness and Green Perceived Benefits on Green Purchase Propensity: The Mediating Role of Green Consumer Confusion" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146589

APA StyleApostolopoulos, N., Makris, I., Deirmentzoglou, G. A., & Apostolopoulos, S. (2025). The Impact of Greenwashing Awareness and Green Perceived Benefits on Green Purchase Propensity: The Mediating Role of Green Consumer Confusion. Sustainability, 17(14), 6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146589