Multi-Dimensional Accessibility Framework for Nursing Home Planning: Insights from Kunming, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How are nursing homes spatially distributed in relation to older adult population needs and what patterns exist across different facility types?

- How does spatial accessibility vary across different transportation modes (walking, public transit, private vehicle) and geographic areas?

- What are the equity implications of current accessibility patterns for different socioeconomic groups and community types?

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Sources

2.3.1. Older Adult Care Facility Data

2.3.2. Demographic and Economic Data

2.3.3. Transportation Network Data

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Nearest Neighbor Index

2.4.2. Kernel Density Estimation

2.4.3. Ratio of Means Method

2.4.4. Gaussian Two-Step Floating Catchment Area Method (Gaussian 2SFCA)

3. Results

3.1. The Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Nursing Homes in Kunming

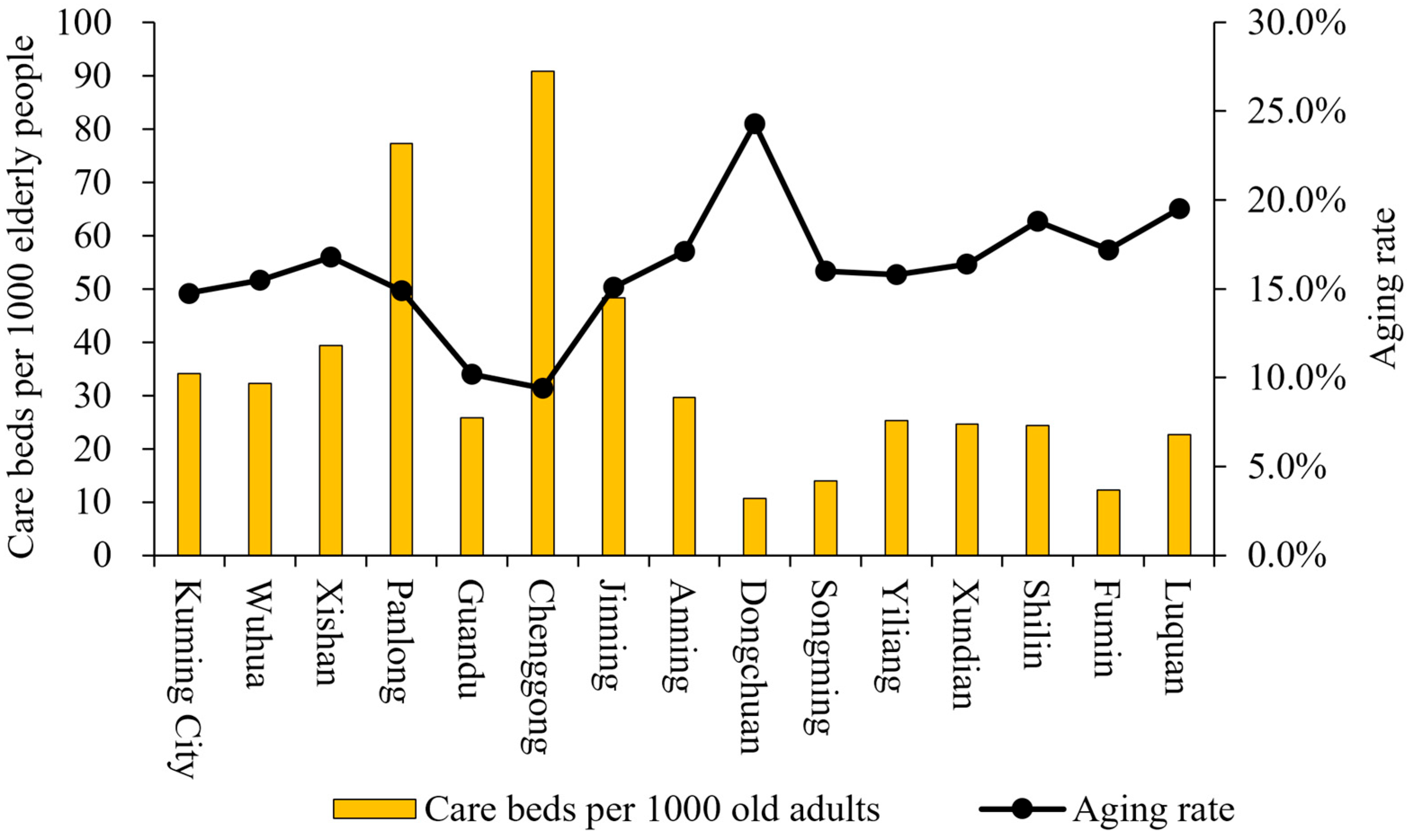

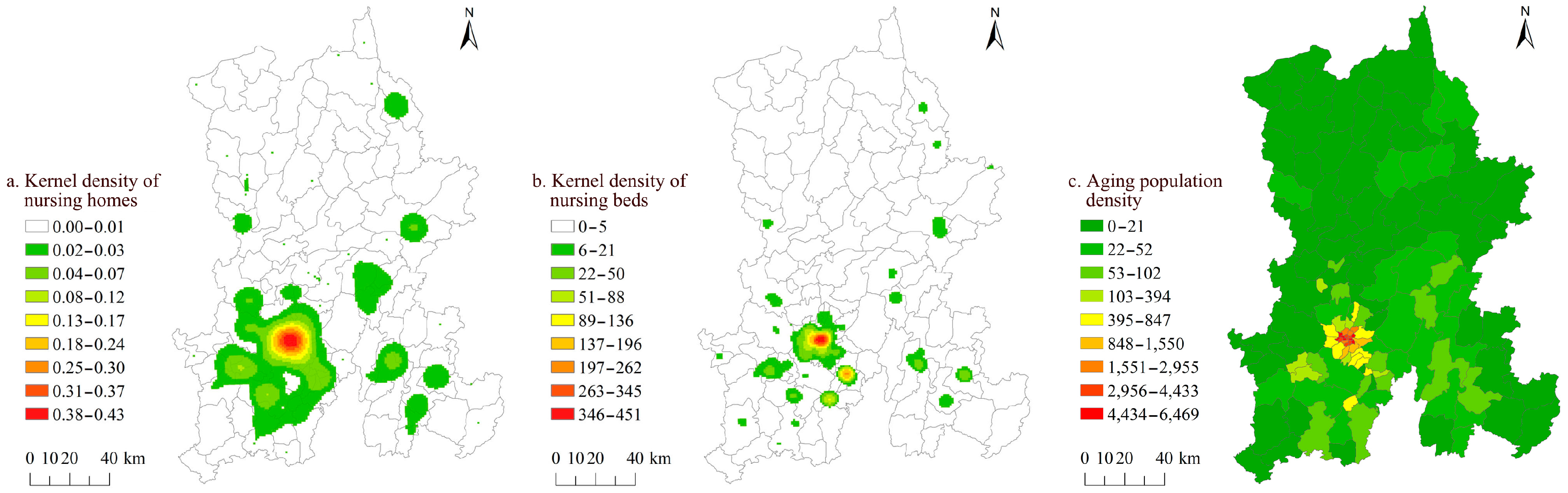

3.1.1. Spatial Coupling Between Nursing Homes and Older Adult Population

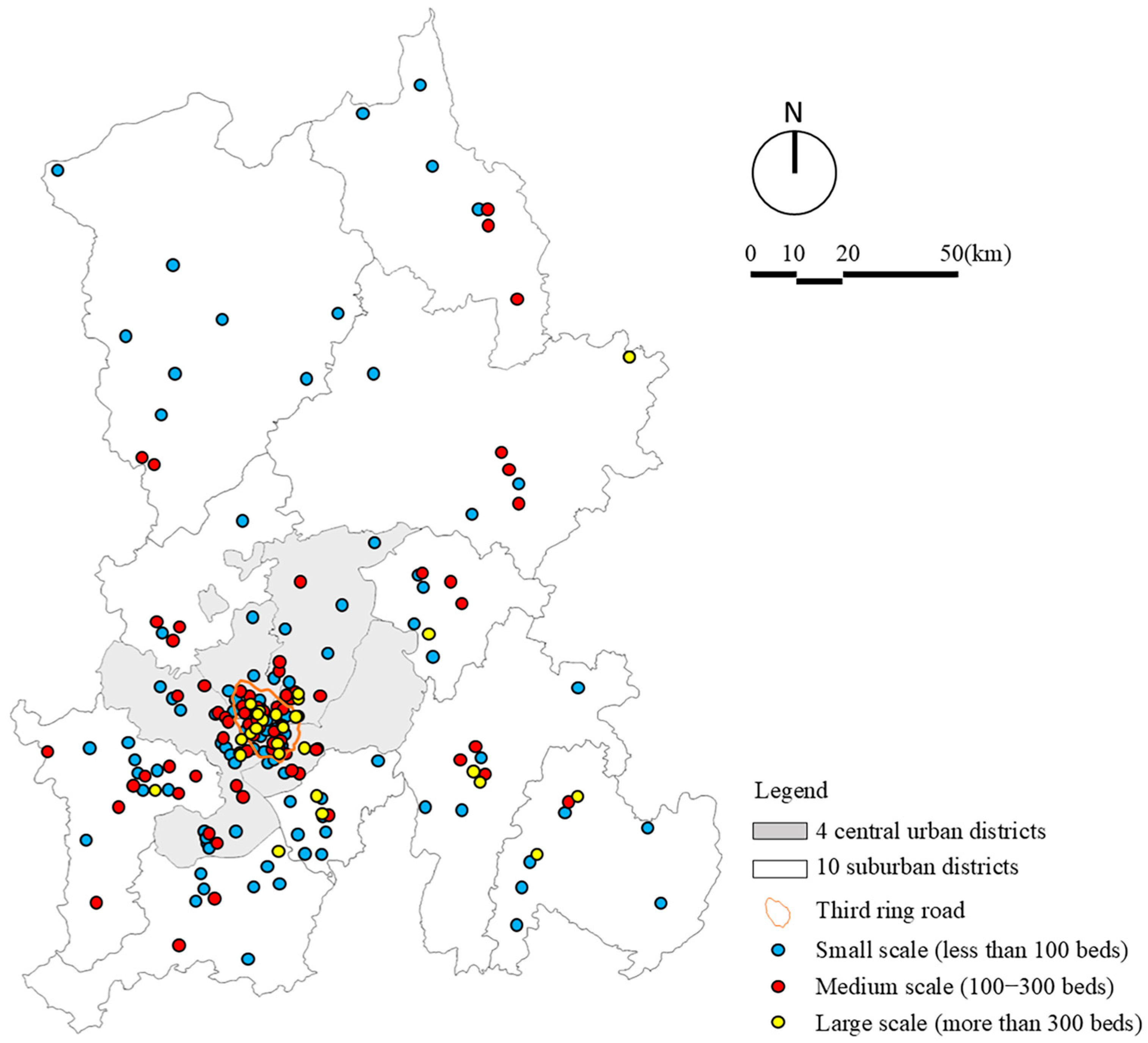

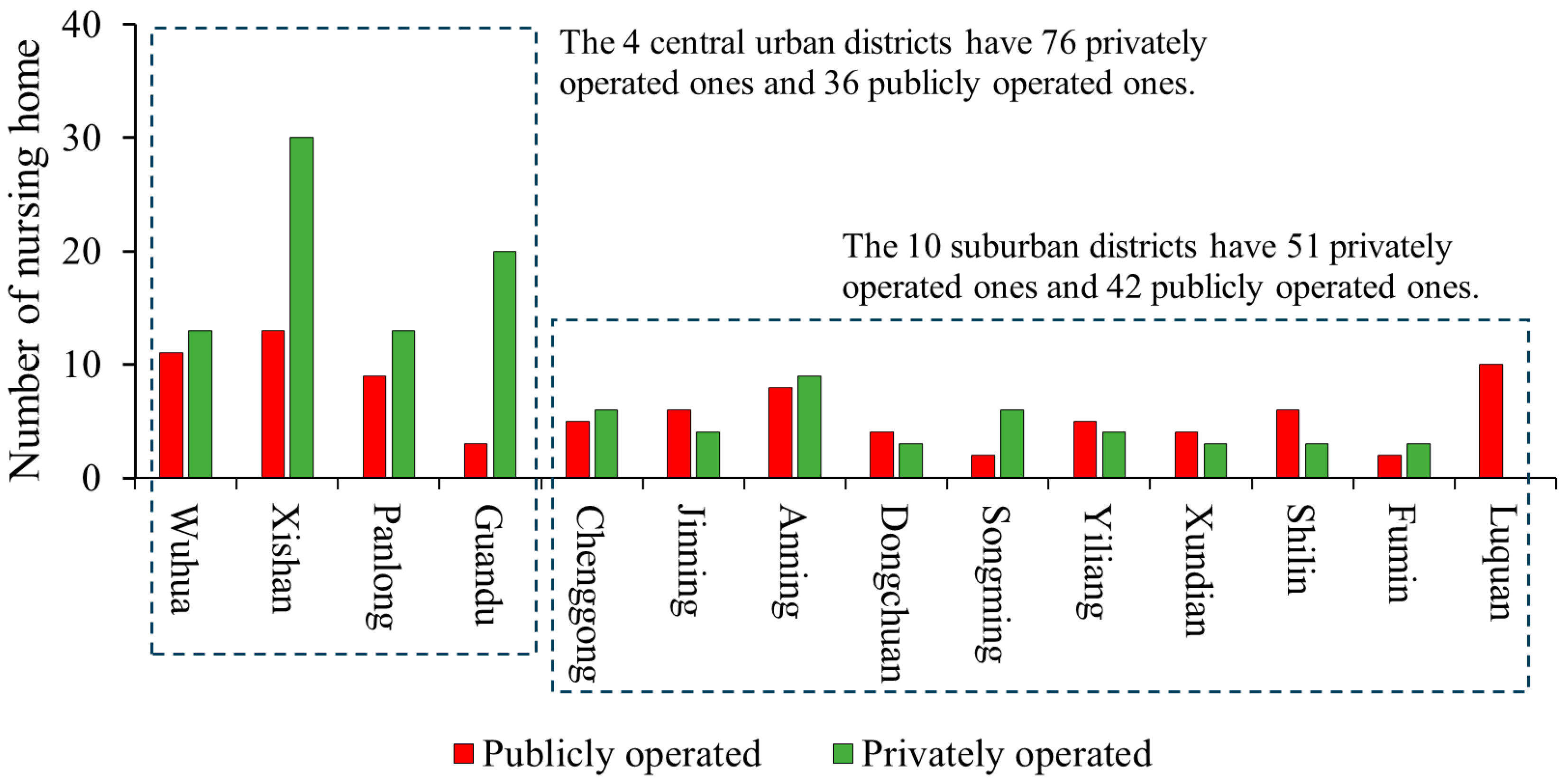

3.1.2. Distribution Characteristics Based on Scale and Operational Nature

3.1.3. Spatial Clustering Characteristics of Nursing Homes

3.2. Accessibility Analysis of Nursing Homes at the Community Level in Kunming

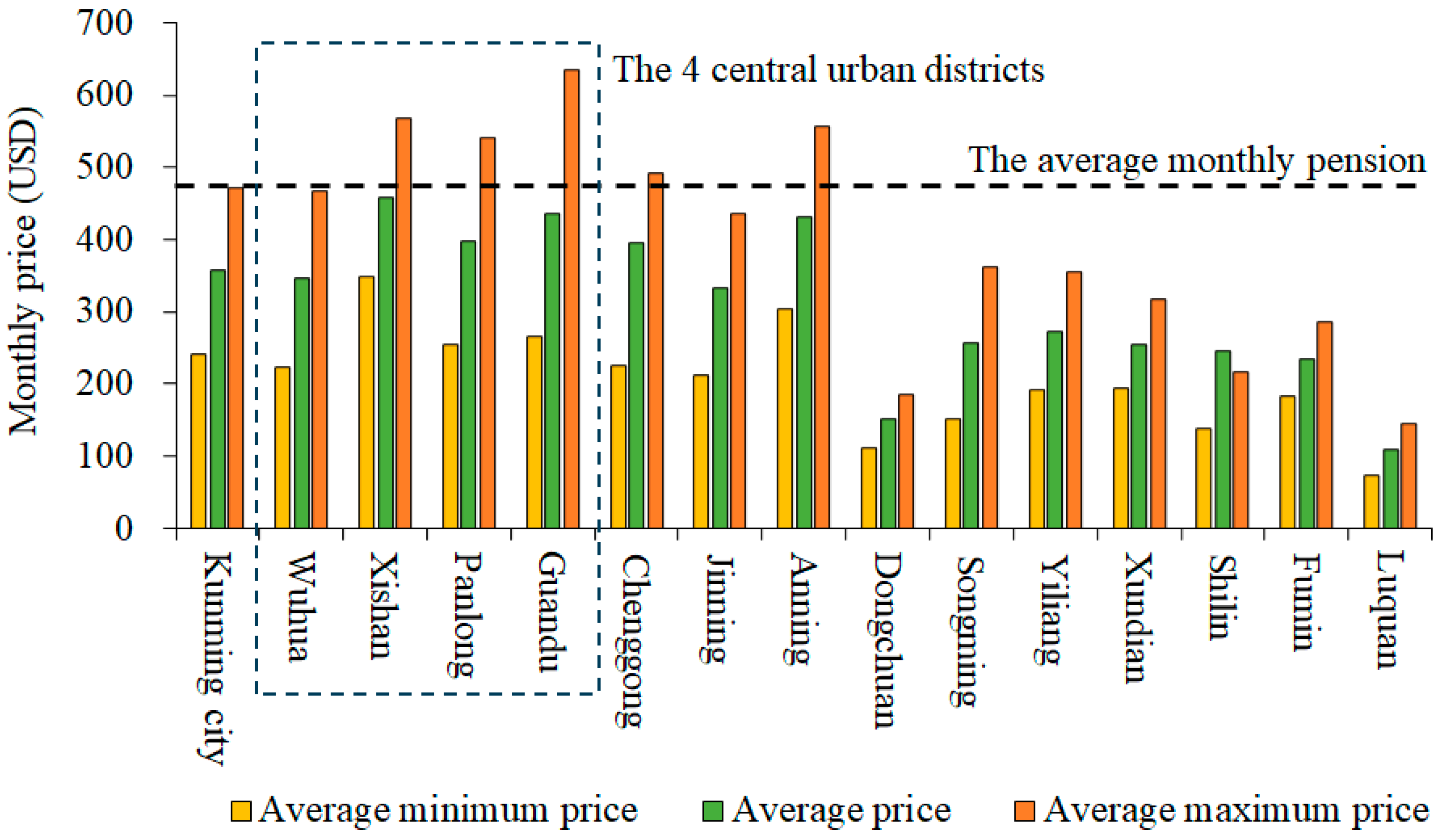

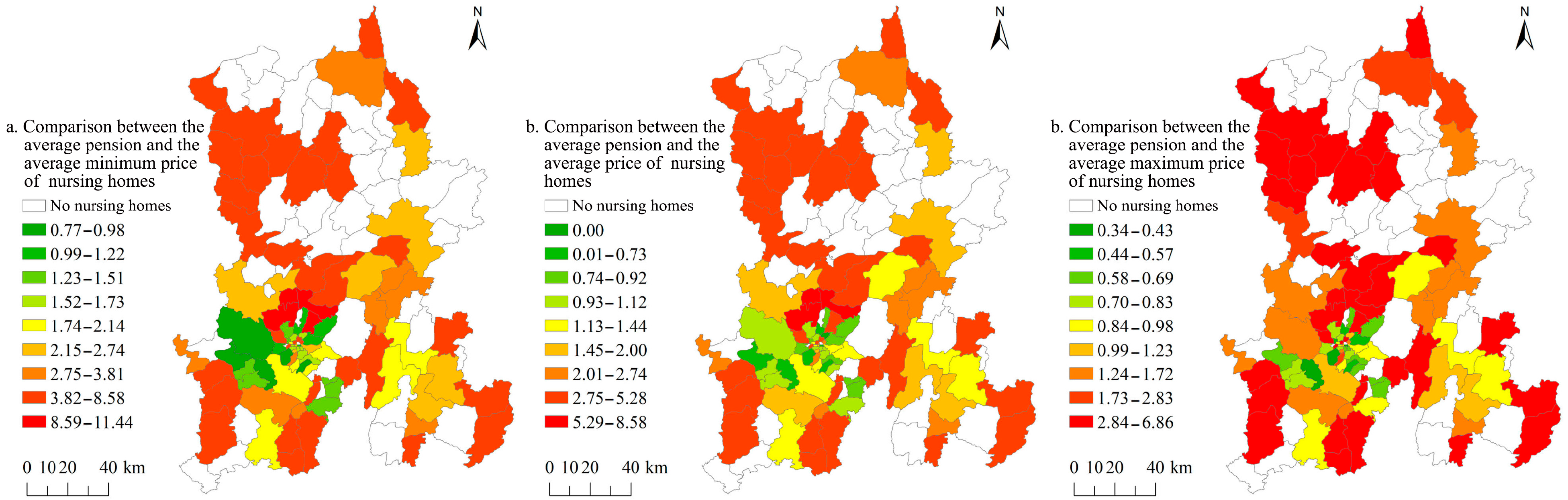

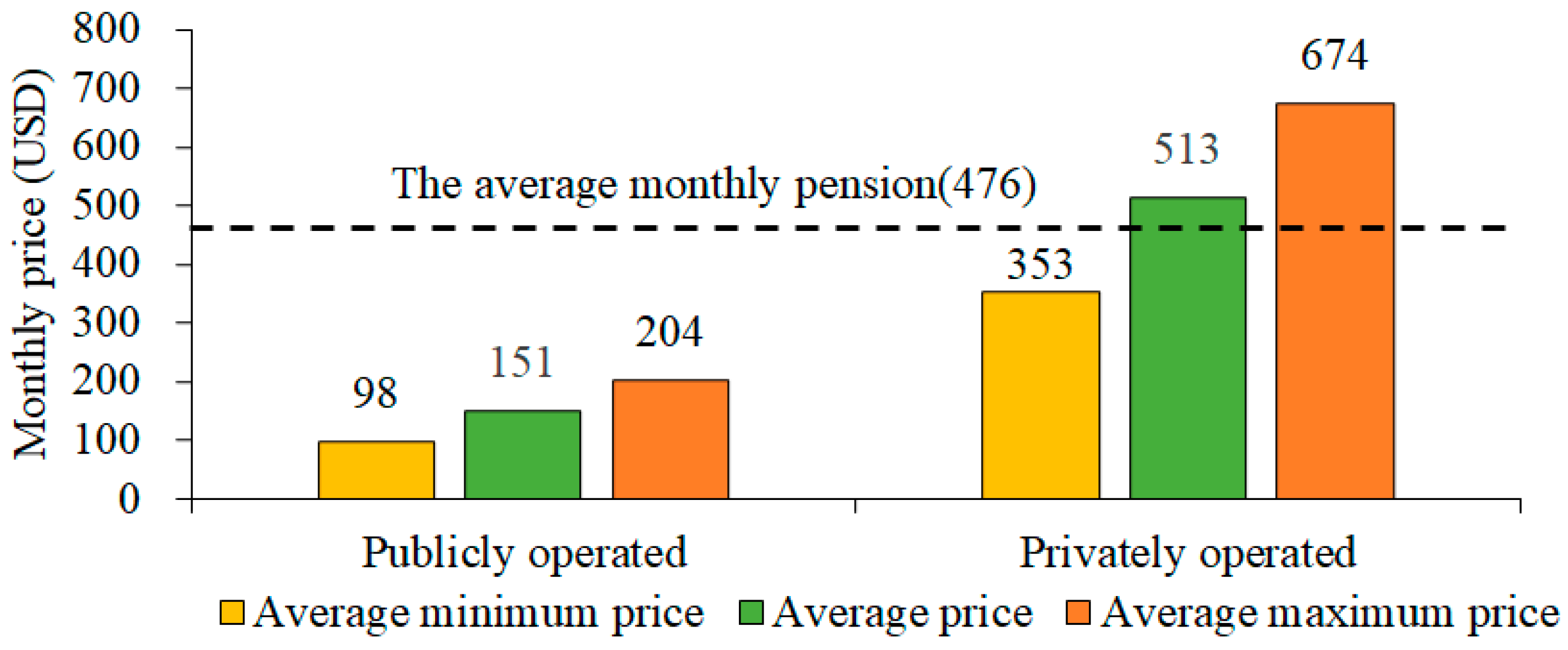

3.2.1. Economic Accessibility of Nursing Homes at the Community Level

3.2.2. Spatial Accessibility of Nursing Homes at the Community Level

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Distribution Patterns and Their Implications

4.2. Multi-Dimensional Accessibility Challenges

4.3. Policy Recommendations

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook. 2024. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Li, Q. Report on the Work of the Government: Delivered at the Third Session of the 14th National People’s Congress. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202503/content_7013163.htm (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Zeng, Y.; Hesketh, T. The effects of China’s universal two-child policy. Lancet 2016, 388, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Peng, P.; Ao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zuo, J.; Martek, I. Equity in public decision-making: A dynamic comparative study of urban–rural elderly care institution resource allocation in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Sworn, K.; Booth, A.; Tsuchiya, A.; Maden, M.; Rosenberg, M. Equity in healthcare access and service coverage for older people: A scoping review of the conceptual literature. Integr. Healthc. J. 2022, 4, e000092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritart, H.; Tuntiwong, K.; Miyazaki, H.; Taertulakarn, S. Disparities in healthcare services and spatial assessments of mobile health clinics in the border regions of Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gong, P.; White, M.; Zhang, B. Research on spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of pension resources in Shanghai community-life circle. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Li, J.; Shi, L.; Liang, H.; Ding, G.; Xu, L. Urban-rural disparities in health care utilization among Chinese adults from 1993 to 2011. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, D.D.; Estrada, L.V.; Alexander, G.L.; Dick, A.; Stone, P.W. Differences in care provided in urban and rural nursing homes in the United States: Literature review. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2021, 47, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. Master plan, plan adjustment and urban development reality under China’s market transition: A case study of Nanjing. Cities 2013, 30, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gong, P.; White, M. Study on spatial distribution equilibrium of elderly care facilities in downtown Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Liu, S. Study on spatial distribution and accessibility of the elderly care institutions in Shanghai. Mod. Urban Res. 2021, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Si, M. A study on the characteristics of spatial distribution of care facilities and capacities for the elderly in Shanghai. J. Archit. 2018, 2, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yao, S. Study on spatial distribution of residential care facilities in Shanghai. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018, 3, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, J. Spatial distribution characteristics and existing problems of privately operated elderly care facilities in Beijing. Beijing Plan. Constr. 2017, 5, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.M.; Alston, L.; Beks, H.; Mc Namara, K.; Coffee, N.T.; Clark, R.A.; Shee, A.W.; Versace, V.L. The application of spatial measures to analyse health service accessibility in Australia: A systematic review and recommendations for future practice. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jia, P. A comparative analysis of accessibility measures by the two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) method. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 1739–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-X.; Chiou, S.-C.; Li, W.-Y. Accessibility and street network characteristics of urban public facility spaces: Equity research on parks in Fuzhou city based on GIS and space syntax model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salze, P.; Banos, A.; Oppert, J.-M.; Charreire, H.; Casey, R.; Simon, C.; Chaix, B.; Badariotti, D.; Weber, C. Estimating spatial accessibility to facilities on the regional scale: An extended commuting-based interaction potential model. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J. Hierarchical two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) method: Measuring the spatial accessibility to hierarchical healthcare facilities in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place 2010, 16, 1038–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Z.; Cheng, Y. Modelling the spatial accessibility of the elderly to healthcare services in Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, G.; Li, C.; Xia, B.; Sun, X.; Chen, S. Use of an E2SFCA method to measure and analyse spatial accessibility to medical services for elderly people in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Deng, Q.; Wang, S.; Wei, L. Equity evaluation of elderly-care institutions based on Ga2SFCA: The case study of Jinan, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, K.; Neutens, T.; De Maeyer, P.; Deruyter, G. A commuter-based two-step floating catchment area method for measuring spatial accessibility of daycare centers. Health Place 2015, 32, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrail, M.R.; Humphreys, J.S. Measuring spatial accessibility to primary care in rural areas: Improving the effectiveness of the two-step floating catchment area method. Appl. Geogr. 2009, 29, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, P.L. Spatial accessibility in suboptimally configured health care systems: A modified two-step floating catchment area (M2SFCA) metric. Health Place 2013, 24, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, F. Measures of spatial accessibility to health care in a GIS environment: Synthesis and a case study in the Chicago region. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2003, 30, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.J.; Brunsdon, C.; Radburn, R. A spatial analysis of variations in health access: Linking geography, socio-economic status and access perceptions. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.T.; Ford, C.L.; Wallace, S.P.; Wang, M.C.; Takahashi, L.M. Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Hulme, C.; Farragher, T.; Clarke, G. Are differences in travel time or distance to healthcare for adults in global north countries associated with an impact on health outcomes? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.; Ohta, R.; Mathews, M. Rural and urban disparities in access and quality of healthcare in the Japanese healthcare system: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.J.; Martin, E.G. Geographic disparities in access to nursing home services: Assessing fiscal stress and quality of care. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 2932–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stineman, M.G.; Xie, D.; Streim, J.E.; Pan, Q.; Kurichi, J.E.; Henry-Sánchez, J.T.; Zhang, Z.; Saliba, D. Home accessibility, living circumstances, stage of activity limitation, and nursing home use. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, P.J. Natural neighborhood networks—Important social networks in the lives of older adults aging in place. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, S.C.; Porter, M.M.; Menec, V.H. Mobility in older adults: A comprehensive framework. Gerontol. 2010, 50, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chu, C.-L.; Ho, C.-S.; Lan, S.-J.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-P. Decision-making factors affecting different family members regarding the placement of relatives in long-term care facilities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.M.; Fraser, F.; Shankardass, K.; Epstein, R.; Khera, J. Are long-term care residents referred appropriately to hospital emergency departments? Can. Fam. Physician 2009, 55, 500–505. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Ding, F.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Guo, T. Demand, mobility, and constraints: Exploring travel behaviors and mode choices of older adults using a facility-based framework. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 102, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau of Kunming. Kunming Statistical Yearbook. 2023. Available online: https://tjj.km.gov.cn/2023tjnj/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Kunming Municipal People’s Government Office. Notice on the Issuance of Kunming’s Three-Year Action TASK Division Plan for Promoting High-Quality Development of Older Adult Care Services (2024–2026). 8 January 2025. Available online: https://www.km.gov.cn/c/2025-01-08/4931867.shtml (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Guidelines for Service Standard System Construction of Senior Care Organization (MZ/T 170-2021). 2021. Available online: https://www.hengyang.gov.cn/DFS//file/2021/12/02/20211202162049621qtbmmb.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Yunnan Provincial Department of Human Resources and Social Security. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Human Resources and Social Security in Yunnan Province in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://hrss.yn.gov.cn/Uploads/NewsPhoto/2024-07-17/0f39c7dc-70fd-4f5b-a735-97dac1dd955d.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Design Specification for Highway Alignment (JTG D20-2017). 2017. Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/glj/202006/P020230330590791909604.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Getis, A. Temporal land-use pattern analysis with the use of nearest neighbor and quadrat methods. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1964, 54, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Shao, H.; Li, Y.; Guan, M.; Tong, J. GIS-Based Analysis of Elderly Care Facility Distribution and Supply–Demand Coordination in the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2025, 14, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, H.A.; Shi, X.; Sargent, J.; Tanski, S.; Berke, E.M. Density estimation and adaptive bandwidths: A primer for public health practitioners. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Ai, T. The visualization and analysis of urban facility pois using network kernel density estimation constrained by multi-factors. Bol. Cienc. Geod. 2014, 20, 902–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Dai, X. Impact of economic accessibility on realized utilization of home-based healthcare services for the older adults in China. Healthcare 2021, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zeng, S.; Namaiti, A.; Zeng, J. Evaluation of supply–demand matching of public health resources based on Ga2SFCA: A case study of the central urban area of Tianjin. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heerden, Q.; Karsten, C.; Holloway, J.; Petzer, E.; Burger, P.; Mans, G. Accessibility, affordability, and equity in long-term spatial planning: Perspectives from a developing country. Transp. Policy 2022, 120, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Han, E.-J.; Kim, H.K. An analysis of the effects of the income level of the family caregivers for the recipients in long-term care facilities on the willingness to pay for use of better services: A cross-sectional study. J. Korean Gerontol. Nurs. 2023, 25, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Beijing Municipal Working Committee on Aging; Beijing Association of the Elderly; China Philanthropy Re-search Institute of Beijing Normal University. Beijing Municipal Report on Elderly Care Development (2023). 2024. Available online: https://mzj.beijing.gov.cn/attach/0/e579da4186d440e7890d97711cc87d91.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Green Qingpu. 54 Older Adult Care Beds Per Thousand Residents! Qingpu Continues to Enhance Older Adult Care Service Capacity Building. 2023. Available online: https://www.shqp.gov.cn/shqp/qpyw/20230417/1113401.html (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Wang, C.; Geng, X. Assessing the spatial equity of the aged care institutions based on the improved potential model: A case study in Shanghai, China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1428424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Li, M. Equity versus efficiency: A spatial analysis of residential aged care resources in Beijing. Chin. J. Sociol. 2023, 9, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cheng, Y.; Tao, Z. Spatial accessibility and equity of residential care facilities in Beijing from 2010 to 2020. Health Place 2024, 86, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Liu, G. Spatial matching relationship between health tourism destinations and population aging in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 095001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Dai, T.; Rosenberg, M.W. Spatial optimization of residential care facility locations in Beijing, China: Maximum equity in accessibility. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E.S. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Glinskaya, E.; Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yip, W. Long-term care system for older adults in China: Policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. Lancet 2020, 396, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, T.; Lan, T.; Chen, C.; Pan, J. The contributions of population distribution, healthcare resourcing, and transportation infrastructure to spatial accessibility of health care. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2023, 60, 00469580221146041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, M.; Jones, S.; Turner, J. Older people, mobility and transport in low- and middle-income countries: A review of the research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Aihara, Y.; Yamasaki, K. The effect of accessibility on aged people’s use of long-term care ser-vice. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 4381–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, F.; Yang, F.; Sun, F.; Li, Y. Demand-driven Urban Facility Visit Prediction. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Civil Affairs Bureau. Shanghai’s “14th Five-Year Plan” for Elderly Care Service Development. 2021. Available online: https://mzj.sh.gov.cn/mz-jhgh/20210928/acb2374791b24a35b39bfd5a2a1c47df.html (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Golant, S.M. Affordable Clustered housing-care: A category of long-term care options for the elderly poor. J. Hous. Elder. 2008, 22, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Travel Mode | Accessibility Level | Accessibility Value | Number of Communities | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private car | Low | 0.0000–0.0007 | 83 | 57.6% |

| Relatively low | 0.0008–0.0025 | 26 | 18.1% | |

| Normal | 0.0026–0.0057 | 18 | 12.5% | |

| Relatively high | 0.0058–0.0104 | 14 | 9.7% | |

| High | 0.0105–0.0286 | 3 | 2.1% | |

| Walking | Low | 0.0000–0.0051 | 101 | 70.1% |

| Relatively low | 0.0052–0.0245 | 23 | 16.0% | |

| Normal | 0.0246–0.0533 | 14 | 9.7% | |

| Relatively high | 0.0534–0.1162 | 4 | 2.8% | |

| High | 0.1163–0.2155 | 2 | 1.4% | |

| Public bus | Low | 0.0000–0.0027 | 91 | 63.2% |

| Relatively low | 0.0028–0.0077 | 22 | 15.3% | |

| Normal | 0.0078–0.0133 | 14 | 9.7% | |

| Relatively high | 0.0134–0.0205 | 13 | 9.0% | |

| High | 0.0206–0.0385 | 4 | 2.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, W.; Xu, G.; Xu, J.; Matsubara, S.; Ma, R.; Ma, M.; Li, H. Multi-Dimensional Accessibility Framework for Nursing Home Planning: Insights from Kunming, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177606

Ding W, Xu G, Xu J, Matsubara S, Ma R, Ma M, Li H. Multi-Dimensional Accessibility Framework for Nursing Home Planning: Insights from Kunming, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177606

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Wenlei, Genyu Xu, Jian Xu, Shigeki Matsubara, Ruiqu Ma, Ming Ma, and Houjun Li. 2025. "Multi-Dimensional Accessibility Framework for Nursing Home Planning: Insights from Kunming, China" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177606

APA StyleDing, W., Xu, G., Xu, J., Matsubara, S., Ma, R., Ma, M., & Li, H. (2025). Multi-Dimensional Accessibility Framework for Nursing Home Planning: Insights from Kunming, China. Sustainability, 17(17), 7606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177606