Abstract

Under the rapid development of the digital economy, the interactive relationship between exports and the digital economy has become an important issue for promoting regional economic growth. Based on the panel data of 31 provinces and municipalities in China from 2012 to 2022, this paper systematically examines the impact of exports on economic growth and the moderating role of the digital economy, and it introduces research and development (R&D) investment to test its mediating mechanism. The research finds that exports significantly promote regional economic growth. The digital economy has a negative moderating effect on the export growth effect, and it is significant in the eastern region but not significant in the central and western regions, showing obvious regional heterogeneity. R&D investment has played a partial mediating role between exports and economic growth. This paper suggests that the government should focus on regional differences, promote the deep integration of the digital economy and exports, enhance technological innovation capabilities, formulate differentiated policies based on local conditions, strengthen the construction of digital infrastructure, optimize the export structure, support the development of R&D-driven enterprises, and build a digital export system that promotes regional coordination and high-quality growth, so as to achieve high-quality coordinated sustainable regional development. This paper also has certain reference value for other developing economies, in promoting the integration of the digital economy and trade.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of a sluggish global economic recovery and the accelerated evolution of international trade patterns, exports, as an important engine driving economic growth, have once again become the focus of attention. For most developing countries, the export-oriented growth model can not only effectively expand external demand and drive output and employment, but it also is a key path to promote industrial structure upgrading and technological progress. Meanwhile, the rapid rise of the digital economy is reshaping the global trading system and economic growth mechanism at an unprecedented speed.

With the wide application of new-generation information technology, the digital economy is no longer a single industrial form, but a systematic growth driver that spans departments and regions. China has gradually entered a new stage of integrated development of “digital and export” against the backdrop of industrial digitalization. The Digital Trade Development and Cooperation Report 2023 shows that the total import and export value of China’s digital services reached USD 371.08 billion in 2022, a year-on-year increase of 3.2%, accounting for 41.7% of service imports and exports [1]. As the core force of technological revolution and industrial transformation, the digital economy is reshaping the export–oriented growth path and has a profound impact on export-oriented countries, especially emerging market economies such as China [2,3]. Digital technology has significantly enhanced enterprises’ export capacity and regions’ economic vitality by improving information efficiency, reducing transaction costs, and optimizing the factor matching mechanism [4]. Multiple empirical studies have shown that digitalization enhances export products’ quality and technical complexity [5,6], and it has also played a profound role in enhancing enterprises’ export resilience, improving green growth level and promoting employment structure optimization [1,7,8]. However, this effect is not linear or uniform. The differences in different regions, industrial structures, and digital infrastructure conditions may lead to enhanced or inhibitory moderating effects in the “export to growth” mechanism, and the performance differences between Eastern and Western China are particularly obvious [9].

Existing studies mainly approach from two dimensions: First, they focus on the direct promoting effect of exports on economic growth and confirm its positive role in aspects such as capital accumulation, technology spillover and job creation. Second, they focus on the impact of the digital economy on growth performance, emphasizing its value in optimizing resource allocation, enhancing total factor productivity and guiding industrial upgrading. However, there are two deficiencies in the current literature: First, most studies take exports and the digital economy as parallel explanatory variables, ignoring the possible interaction between and mechanisms of the two. In particular, whether the digital economy plays a moderating role in the process of exports affecting economic growth still lacks systematic examination. Secondly, existing studies often overlook the significant heterogeneity among regions in terms of digital infrastructure, industrial structure and the degree of export dependence and fail to reveal the differentiation characteristics among exports, digital economy and economic growth in different regional mechanisms.

This study makes the following research contributions: First, it empirically identifies the moderating effect of the digital economy on the relationship between export and regional economic growth, using Chinese provincial panel data from 2012 to 2022. Second, it tests the mediating role of R&D investment, contributing to the understanding of the “export–innovation–growth” mechanism within the digital context. Thirdly, it conducts regional heterogeneity analysis, revealing important differences across eastern, central, and western regions, and offering practical insights for targeted policy formulation.

This article’s structure is as follows: The second part is a literature review and hypotheses, reviewing the research related to exports, digital economy and economic growth and proposing research hypotheses. The third part is model setting and variable description, introducing the construction of the empirical model, variable definitions and data sources. The fourth part is the empirical results analysis. The fifth part is the discussion; the sixth part is policy recommendations, and the seventh part is the conclusions.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Export-Led Economic Growth

The export-led growth theory provides the theoretical basis for this paper. This theory holds that exports are the result of economic growth and one of its key driving forces. Especially in the context of developing countries, exports have become an important channel for promoting capital accumulation and technological progress through paths such as expanding international markets, attracting foreign capital, creating jobs, and promoting industrial upgrading [10,11]. Furthermore, export activities can form economies of scale in the production process, optimize resource allocation, bring about significant technological spillover effects, and thereby enhance total factor productivity. Helpman and Krugman further pointed out that foreign trade in an open economy can strengthen market competition, promote specialized division of labor and capital accumulation, and accelerate the optimization of industrial structures and technological upgrading [12]. Overall, the export-oriented growth theory reveals the crucial role of exports in stimulating production efficiency, enhancing international competitiveness, and supporting long-term economic growth.

Many empirical studies also support the above theory. For instance, Awokuse found, based on panel data from multiple countries, that export expansion significantly increased the GDP growth rate of developing countries [13]. Hausmann et al. pointed out that export diversification is conducive to improving a country’s foreign trade structure and comprehensive competitiveness [14]. Exports can also promote technological upgrading through the mechanism of technology absorption and knowledge diffusion, thereby driving productivity improvement [15,16].

For China, exports have been a key force driving economic growth since the reform and opening up. By deeply integrating into the global value chain, China has developed a typical export-oriented economic system and has gradually become the world’s largest manufacturing and exporting country. Studies show that exports not only significantly drive GDP growth, but also have a positive promoting effect on enterprise innovation activities [17]. For instance, before and after enterprises enter the export market, their allocation in terms of fixed assets and R&D investment often undergoes significant adjustments, reflecting the incentive effect of export behavior on innovation resources. Furthermore, the driving effect of exports on economic growth also shows obvious regional differences. With the advantages of industrial agglomeration and ports, the marginal effect of exports on economic growth in the eastern coastal areas is significantly higher than that in the inland areas of the central and western regions.

Although existing studies have generally verified that exports positively impact economic growth, this relationship may be restructured. The expansion of information technology, platform economy and digital infrastructure is changing the traditional trade chain and resource allocation mechanism. Moreover, the differences in industrial structure, export dependence and technological level among different regions may lead to the heterogeneity of the marginal effect of exports on growth in the spatial dimension. Therefore, it is necessary to start from a new background and combine regional data to re-examine the path and intensity of the effect of exports on economic growth. Therefore, this paper proposes the first research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Exports have a significant positive impact on regional economic growth.

2.2. The Moderating Role of Digital Economy

With the development of information technology, the digital economy has become an important variable influencing the macroeconomic structure and micro-behavior. Relevant studies show that the digital economy, as a cross-industry systemic force, is changing the traditional export path and its impact on economic growth [4]. For Industrial Organization Theory and structural adjustment mechanisms, the digital economy may enhance or weaken the marginal growth effect of traditional foreign trade by reducing information asymmetry, reconfiguring the matching mode of supply and demand, and optimizing production processes. Especially among different regions, due to differences in digital infrastructure construction and industries’ matching capabilities, its regulatory capabilities also show significant spatial heterogeneity [9].

Digital economy has enhanced enterprises’ ability to participate in global trade by improving information efficiency, reducing transaction costs, and expanding market boundaries, significantly improving enterprises’ export performance and growth resilience. Compared with traditional trade routes, new models brought about by digitalization, such as the platform economy, intelligent supply chain, and digital service outsourcing, are expanding the transmission mechanism and applicable conditions between exports and economic growth [4]. The digital economy can significantly enhance enterprises’ export product quality by improving process productivity and product productivity. This effect is particularly prominent in high-tech industries, general trade enterprises, and well-governed enterprises [6,18]. Ding et al. indicated that digital transformation can effectively promote the upgrading of export products, especially in domestically funded enterprises with a good institutional environment and strong innovation capabilities. It mainly functions through paths such as stimulating innovation, reducing costs, and improving labor efficiency [5]. The digital economy has optimized the export technology structure. This effect has a nonlinear threshold effect and relies on a higher level of technology market maturity and absorption capacity [19]. Wen et al. also found that digitalization significantly enhanced the innovation investment of enterprises by supporting differentiated competition strategies. High-viability enterprises benefited more significantly, while there was a certain inhibitory effect on cost-oriented strategies [20].

From a macro perspective, the impact of the digital economy on the relationship between exports and economic growth is also reflected in its reshaping of overall industrial efficiency and regional development models. Wang and Wang found that the digital economy could significantly enhance green economic growth performance by promoting technological innovation and industrial structure upgrading, and the intensity of research and development strengthened this mechanism [8]. Wang et al. pointed out that digitalization has a positive effect on alleviating regional income inequality and promoting inclusive growth by reshaping employment structure, increasing labor productivity and income share [2]. Zhao and Said further confirmed the guiding role of the digital economy in optimizing employment structure and upgrading industries in the eastern and central regions [3].

Furthermore, the digital economy has a significant heterogeneous impact on the technological complexity of exports and trade resilience. This effect is most obvious in the eastern region, while it even shows an inhibitory effect in the western region. Digital economy has a significant spatial spillover effect, with the eastern and central regions demonstrating a stronger driving capacity. The main transmission mechanism is knowledge spillover and industrial structure optimization [1]. Digitalization significantly enhances enterprises’ export resilience. The mechanism is reflected in the enhanced stability of the supply chain, the optimization of cost control, and improvements in market response capabilities, and the performance is strongest in the eastern region [9]. Li et al. further demonstrated that the digital economy promotes inter-regional trade flows by stimulating market demand and reducing trade costs, and it has a greater impact on underdeveloped and non-border provinces, possessing a spatial spillover effect [7].

In conclusion, the digital economy improves enterprises’ export performance through technology and efficiency; it also significantly influences the direction and intensity of the relationship between exports and economic growth through industrial restructuring, employment structure optimization, and institutional innovation. Its role has obvious regional heterogeneity, nonlinear mechanism characteristics, and cross-level influence, demonstrating a strong structural regulatory function. Therefore, from the perspective of the moderating mechanism, this paper proposes the second research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

The level of the digital economy will significantly moderate the direction and intensity of the impact of exports on economic growth.

2.3. The Mediating Role of R&D Investment

Endogenous Growth Theory emphasizes that technological progress, knowledge accumulation, and R&D investment are the fundamental sources of sustained economic growth [21,22]. Under the open economic structure, exports directly drive economic output and promote the continuous progress of enterprises in technology, management, and product design by stimulating the “learning-by-exporting” effect [23]. During this process, export can significantly enhance enterprises’ technological absorption capacity, accelerate knowledge transfer, and promote resource reallocation, thereby forming a key mediating transmission mechanism between technological progress and economic growth [16].

The existing literature has summarized three typical paths in which exports promote technological innovation. First, enterprises face higher technical thresholds and quality standards when participating in international market competition, and thus are forced to increase R&D investment to maintain their products’ competitiveness [24]. Secondly, the profit growth brought about by export expansion provides enterprises with more financial resources to support their technological upgrading and innovation [23]. Again, knowledge spillover, process standards, and technology introduction generated during the export process provide a “learning-by-exporting” effect for local enterprises, thereby promoting local innovation capabilities improvement [19].

In the context of China, with the continuous advancement of the “innovation-driven development strategy”, R&D investment has become an important indicator for measuring high-quality regional development. The role of exports in enhancing the enthusiasm for local research and development has become increasingly significant. Take the eastern coastal areas as an example. Export enterprises often have strong capital strength and technological accumulation capabilities. Their export earnings are more likely to be transformed into research and development funds and innovation achievements, thereby generating continuous and significant spillover effects in industrial upgrading and economic growth.

Empirical research has also confirmed the close correlation between exports and technological innovation. A single export has a negative effect on price increase and productivity, while a single innovation has a significant positive impact. The combination of the two shows a complementary effect. Studies show that if enterprises possess certain innovation capabilities before entering the international market, they will be more likely to achieve sustained growth in their outward-oriented development [25]. To sum up, exports have the function of directly promoting economic growth and may form an internal mechanism path of “export–innovation–growth” by promoting R&D investment. Therefore, this paper proposes the third research hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3:

Exports indirectly drive regional economic growth by increasing the level of R&D investment.

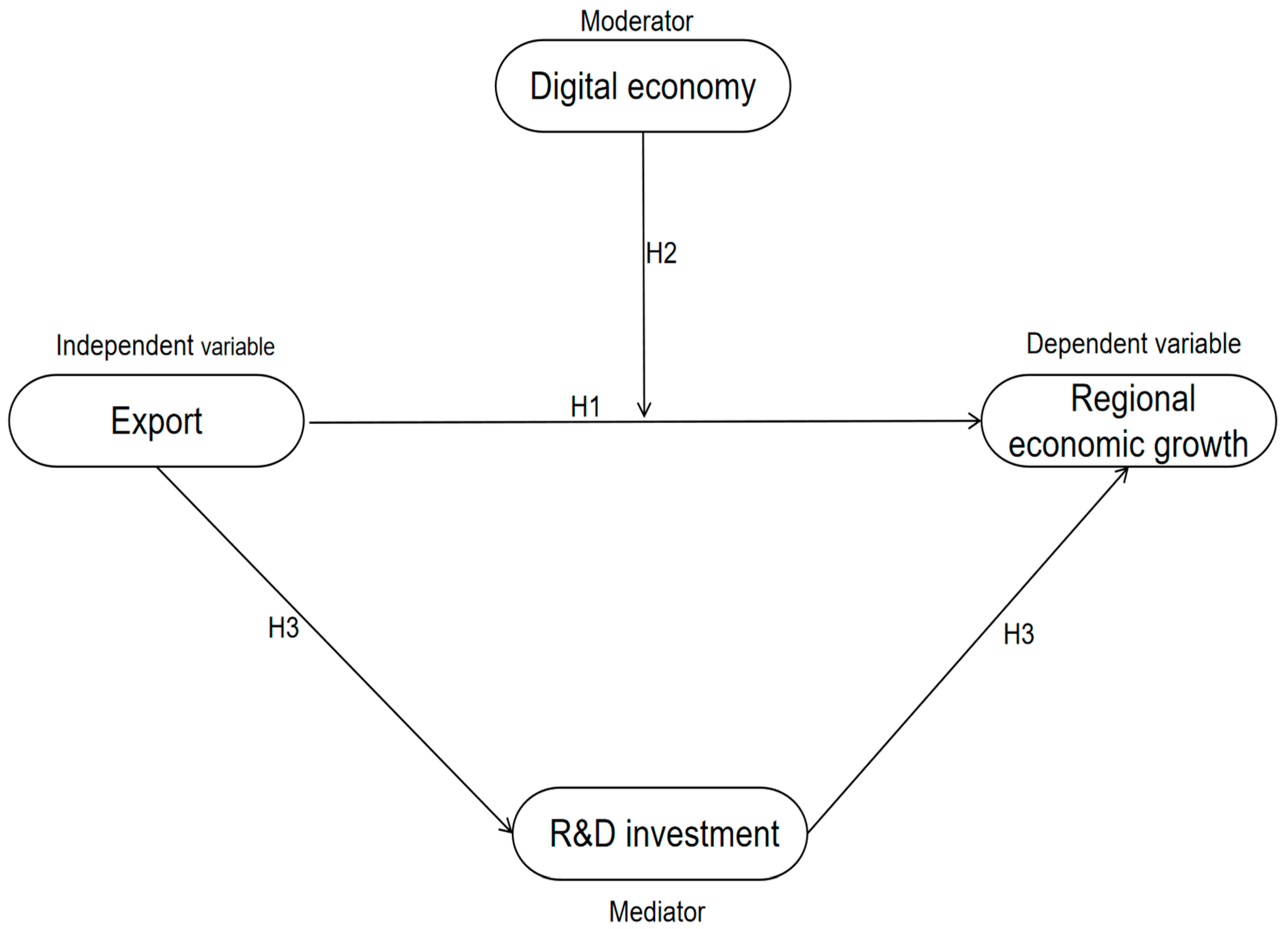

Figure 1 shows the research framework.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized dynamic relationships among the variables. H1 denotes the direct impact of exports on regional economic growth. H2 refers to the moderating effect of the digital economy, which may strengthen or weaken the export–growth nexus depending on regional digital readiness. H3 reflects the mediating role of R&D investment in transmitting the effect of exports on economic growth through technological innovation.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Description

This paper selects the provincial panel data of 31 provincial administrative regions in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) from 2012 to 2022 as a sample. This time range, from 2012 to 2022, is chosen for both policy relevance and data availability. In 2012, the Chinese government initiated the “Broadband China” strategy, which marked a major milestone in the institutional promotion of digital infrastructure and the digital economy. Furthermore, statistical coverage of most digital economy indicators at the provincial level began in 2012, allowing for consistent data collection. The data have obvious cross-temporal and cross-regional characteristics and are suitable for empirical testing of the dynamic relationship among exports, the digital economy, and regional economic growth. Among them, economic variables such as regional gross domestic product, total export amount, number of employed people, and government expenditure are derived from the China Statistical Yearbook, Statistical Yearbook of China’s Provinces, and China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook. The indicators of the digital economy are derived from the Statistical Bulletin of the Telecommunications Industry, the Report on the Development of China’s Internet, and the Digital Inclusive Finance Index released by the Alibaba Research Institute. The data on R&D investment mainly come from the China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook and the statistical bulletins of various provinces and cities.

To improve data comparability and measurement stability, except for proportional-type indicators, all amount and quantity-type indicators were processed by natural logarithm (LN). Finally, a total of 341 observed values of the balance panel data were formed. Data collation and processing were all accomplished using Stata 18 software.

3.2. Variable Description

The research variables are specifically defined as follows:

Dependent Variable: Regional gross domestic product (LNRGDP), which is used to measure the level of regional economic growth. The annual regional GDP of 31 provinces and municipalities is taken and processed as the natural logarithm.

Independent Variables: Total export volume (LNX), which represents the export level of each region, measured by the total export amount of each province and city, and takes the natural logarithm.

Moderating Variables: Digital economy development level (DE), which is used to measure the digital development degree. This paper selects 20 indicators related to information infrastructure, digital industry, digital application and digital technology capabilities to construct a comprehensive index, including the following: number of Internet domain names, number of Internet access ports, and number of Internet broadband access users; density of mobile base stations, penetration rate of mobile phones, and length of long-distance optical cables per unit area; proportion of software business revenue in GDP, proportion of information technology service revenue in GDP, and number of employees in the information service industry; proportion of total telecommunications business volume in GDP, proportion of e-commerce transaction enterprises, and proportion of enterprise e-commerce in GDP; number of computers used per 100 people in an enterprise and number of websites owned per 100 enterprises; the Digital Inclusive Finance Index; and the full-time equivalent of R&D personnel in industrial enterprises, R&D expenditure, number of R&D projects, transaction value of technology contracts, and number of patent authorizations. In this paper, the entropy method is adopted to standardize and integrate the above multi-dimensional indicators through weighting, calculate the comprehensive digital economy index, and reflect the relative differences in the digital development levels of various regions. The digital economy index is constructed using 20 sub-indicators that reflect four dimensions: digital infrastructure, digital industry, digital application, and digital innovation. This multidimensional structure is consistent with previous studies [1] and reflects the comprehensive nature of regional digital development. We apply the entropy weight method to objectively assign weights to each indicator. The data are standardized using the min–max normalization method prior to weighting, and outliers are treated via 1st and 99th percentile trimming.

Mediating Variables: Research and development investment (R&D investment), which measures the level of scientific and technological innovation investment in various regions. The annual R&D expenditure of 31 provinces and municipalities is used as an indicator, and the natural logarithm is taken.

Control Variables: To control the influence of other economic factors on the regional GDP, the following control variables are introduced in this paper: (1) Employment scale (LNE): expressed in terms of the number of employed people in each province and city, it reflects the supply situation of human capital and takes the natural logarithm. (2) Government expenditure (GE): expressed as the proportion of government expenditure to GDP, it measures the intensity of local fiscal policy intervention. (3) Industrial structure (IS): as an alternative control variable in the robustness test, the proportion of the added value of the secondary industry in GDP is adopted to reflect the degree of industrialization of the regional industrial structure. Table 1 shows a summary table of variable definitions and processing methods.

Table 1.

Summary table of variable definitions and processing methods.

To fully understand the distribution characteristics and basic situations of each variable, this paper conducts descriptive statistical analysis on the variables, and Table 2 shows the results.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

3.3. Empirical Model Setting

To systematically analyze the effect mechanism of exports on regional economic growth and the moderating effect of the digital economy and the mediating role of R&D investment, this paper constructs three basic models: a regression model, moderating effect model, and mediating effect model.

Before estimating the panel regression model, this paper tested for the stationarity of the main variables using the Levin–Lin–Chu (LLC) unit root test. LLC assumes a common unit root process across cross-sectional units and is appropriate for strongly balanced panel data, such as the provincial-level dataset used in this study. Table 3 shows the results that all variables are stationary at level, confirming that they are integrated into order zero (I (0)). This supports the use of fixed effects panel regression models.

Table 3.

Panel data stationarity test.

3.3.1. Baseline Regression Model

Firstly, to examine the direct impact of exports on regional economic growth, a regression model is constructed:

Here, i represents the province and t represents the year; LNRGDP represents the logarithm of regional GDP, LNX represents the logarithm of export amount, CV is the set of control variables (including the number of employed people (LNE), and government expenditure (GE)), is the individual fixed effect, is the time fixed effect, and is the error term. If > 0 and significant, then Hypothesis 1 is supported: exports significantly promote regional economic growth.

3.3.2. Moderating Effect Model

To examine whether the digital economy moderates the path in which exports affect economic growth, the interaction term is introduced to construct the following model:

Here, LNRGDP represents the logarithm of the regional gross domestic product and measures the level of regional economic growth; LNX is the logarithm of the export amount; DE stands for the digital economy level;

is the interaction term, used to test the moderating effect; CV represents the control variable matrix (including the employment scale (LNE) and government expenditure (GE)); are the fixed effects representing the province and the year, respectively; and is the error term. If the coefficient of the interaction term is significant, it indicates that digital economy has a moderating effect on the relationship between exports and economic growth. If the coefficient is positive, it indicates that the digital economy has a reinforcing effect on export growth; if it is negative, there may be a weakening or substitution effect.

3.3.3. Mediating Effect Model

To explore whether exports indirectly drive economic growth by increasing R&D investment, a mediating effect model was constructed using the three-step method.

Step 1: Verify the total effect of exports on economic growth.

Step 2: Examine whether exports significantly affect the mediating variable (R&D investment).

Step 3: Introduce both exports and R&D investment simultaneously to test whether there is a mediating effect.

Among them, represents the logarithm of the R&D investment of the i province in the t year. It is introduced as a mediating variable to depict the possible indirect path of technological innovation investment between exports and economic growth. If is significant in the second step, is significant in the third step, and is smaller than in the first step (but still significant or not significant), it indicates that exports indirectly affect economic growth to a certain extent through R&D investment, and there is a partial mediating effect.

The design of this model is conducive to revealing whether the transmission path of exports to economic growth depends on regional technological innovation capacity, and it provides theoretical support for understanding the coupling relationship between export-oriented economy development and the innovation-driven strategy.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

The collinearity test results show that the variance inflation factor (VIF) of each variable is less than 4, indicating that there is no serious multicollinearity problem in the model. Meanwhile, it has passed the Hausman test and is suitable for estimation using the fixed effects model. The regression results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Regression results for the effect of export on regional economic growth.

Column (1) is the model without control variables. The results show that exports (LNX) have a significant positive impact on regional gross domestic product (LNRGDP) with a coefficient of 0.349 and pass the test at the significance level of 1%. This indicates that exports, as an important component of export-oriented economic activities, remain one of the significant driving factors for regional economic growth in China.

Column (2) introduces employment scale (LNE) and government expenditure (GE) as control variables in the model. Although the regression coefficient of exports drops to 0.127, it is still significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that its economic growth effect remains robust after controlling for related factors. Among them, the regression coefficient of the employment scale is 0.596, showing a significant positive relationship. This indicates that the expansion of labor resources can enhance the production capacity and market vitality of the region and contribute to driving economic growth. On the contrary, the regression coefficient of government expenditure (GE) is −3.500, significantly negative, which may be related to problems such as low fiscal expenditure efficiency and unbalanced investment structure in some regions. For instance, some local fiscal expenditures tend towards administrative management or inefficient investment, failing to be effectively transformed into actual output. Instead, they may have suppressed the effective allocation of market resources.

Overall, exports still play a core role in promoting regional economic growth. Moreover, after controlling for labor and fiscal factors, the conclusion remains robust, and Hypothesis 1 has been preliminarily verified.

4.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

To further examine whether the digital economy will be moderating the impact of exports on economic growth, this paper constructs the interaction term between exports (LNX) and digital economy level (DE), and Table 5 shows the results. The coefficient of interaction term is −0.202 and passes the statistical test at the significance level of 5%, indicating that the digital economy has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between exports and economic growth. In other words, although exports themselves still have a significant positive impact on regional GDP (LNRGDP), as the digital economic development level improves, their positive effect weakens instead.

Table 5.

Moderation effects of digital economy on the export–growth relationship.

This is a “inhibitory moderating effect”, which may reflect the following mechanisms: First, although the construction of digital infrastructure in some regions is advancing rapidly at present, its support for traditional manufacturing or export-oriented industries is still limited, and the large-scale transformation of digital empowerment has not yet been fully achieved. Second, digital development may have an impact on some labor-intensive industries, reducing their marginal output in the export process and thereby affecting the strength of exports in driving economic growth. Thirdly, there are still compatibility issues between the digital economy and traditional foreign trade models. For instance, emerging models such as cross-border e-commerce and intelligent logistics have not yet fully covered the leading industrial clusters.

After controlling for employment scale (LNE) and government expenditure (GE), the model had strong explanatory power (R2 overall = 0.944), and the regression coefficients were generally robust, further supporting the preliminary verification of research Hypothesis 2.

4.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

To explore the influence path of exports on regional economic growth, this paper introduces R&D investment (LNRD) as a mediating variable and uses the classic three-step regression method to test the mediating effect. Table 6 shows the results. Among the results of each column, columns (1), (3), and (5) are models without controlling for other variables, while columns (2), (4), and (6) incorporate two control variables, namely employment scale (LNE) and government expenditure (GE), to enhance the explanatory power and robustness of the models.

Table 6.

Mediating effect analysis.

The first step is that columns (1) and (2) take regional gross domestic product (LNRGDP) as the dependent variable to examine the direct impact of exports (LNX) on economic growth. In Model (1) without controlled variables, the regression coefficient of LNX was 0.349. After controlling for variables, it decreased to 0.127 in Model (2). However, both were significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that exports have a significant positive impact on regional economic growth, and this impact remains robust after controlling for key variables.

In the second step, columns (3) and (4) take the R&D investment (LNRD) as the dependent variable to examine the impact of exports on the mediating variable. In the model without control variables, the regression coefficient of LNX to LNRD was 0.527, which decreased to 0.268 in the model with control variables added, but it was still significant at the 1% level. This indicates that exports have significantly promoted regional R&D investment, verifying the existence of the first intermediary path.

In the third step, in columns (5) and (6), the exports and R&D investment (mediating variable) were simultaneously included in the regression model. The results show that in column (5) without control variables, the coefficient of exports to GDP is −0.0246, and in column (6) after control variables, it is −0.0446. Both are significantly negative at the 5% and 1% levels, while the coefficients of R&D investment are 0.667 and 0.674, respectively, and are highly significant. This result indicates that, with or without controlling variables, R&D investment plays a partial mediating role between exports and economic growth; that is, exports indirectly drive regional economic development by promoting R&D activities.

It should be pointed out that although exports remain significant after the introduction of mediating variables, the coefficient direction shows a negative change, which may reflect the promoting effect of exports on economic growth. After considering the research and development channels, it is partially interpreted, forming a “weakening mediating effect”. This also indicates that the paths through which exports affect economic growth are not singular. Besides technological innovation, there may also be other paths such as employment promotion, industrial structure upgrading, and capital accumulation.

For control variables, employment (LNE) has always been positive and significant in columns (2), (4), and (6), reflecting that abundant labor resources play a fundamental role in economic development. However, government expenditure (GE) shows a certain degree of instability in the model. Its impact on economic growth is not significant in column (6), which may be related to the efficiency of fiscal fund allocation in different regions and its overlap with R&D investment.

In conclusion, research Hypothesis 3 has been verified. Exports not only have a direct role in promoting economic growth but can also have an indirect impact by promoting investment in research and development, indicating that technological innovation has gradually become one of the core transmission mechanisms of export-oriented development.

4.4. Robustness Analysis

To enhance the results’ reliability, this paper conducts robustness tests from multiple dimensions to verify whether the estimation results are sensitive to the model settings and sample processing. Specifically, it includes lagging variable substitution, control variable replacement, sample exclusion processing, and extreme value control. The regression results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Robustness analysis.

Firstly, considering the potential endogeneity problem and dynamic correlation between exports and economic growth, export (LNX) is replaced with its one-period lag value (L.LNX) in Model (1). The results show that the coefficient of the lag variable is 0.0770 and the significance level is 1%, which is consistent with the direction of the model. This approach captures the delayed effect of exports on regional GDP and helps mitigate simultaneity bias that may arise from reciprocal causation. The regression results using the lagged export variable remain consistent with the baseline findings, which further confirms our conclusions’ robustness. This indicates that the lag impact of exports on economic growth is still significant, supporting the rationality of the causal sequence. Secondly, in Model (2), a structural robustness test is conducted. The government expenditure (GE) in the control variables is replaced with the industrial structure (IS) to examine the impact of control variable settings on the results. The results show that the coefficient of export remains significant (0.231, p < 0.001), while the coefficient of industrial structure is −3.073 (p < 0.001), and the direction is in line with economic expectations, indicating that the estimation results are robust under the control of structural changes. Thirdly, in Model (3), the year 2020, which was severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, was excluded to conduct the sample exclusion test. The results show that regression coefficient of export remains positive and significant, indicating that even after excluding the samples of major external shocks, the positive correlation between exports and economic growth still holds. Finally, Model (4) introduces winsorization processing, truncating the main variable between the 1% and 99% quantiles to alleviate the interference of extreme values on parameter estimation. The results show that the regression coefficient of the export is 0.0999 and remains highly significant, indicating that the results do not rely on extreme observations and have strong outlier robustness.

To sum up, the core findings of this paper show strong robustness to different model settings, selection of control variables, perturbation of sample years, and handling of outliers. This further enhances the empirical support for the positive effect of exports on economic growth and verifies the reliability and their extrapolation.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

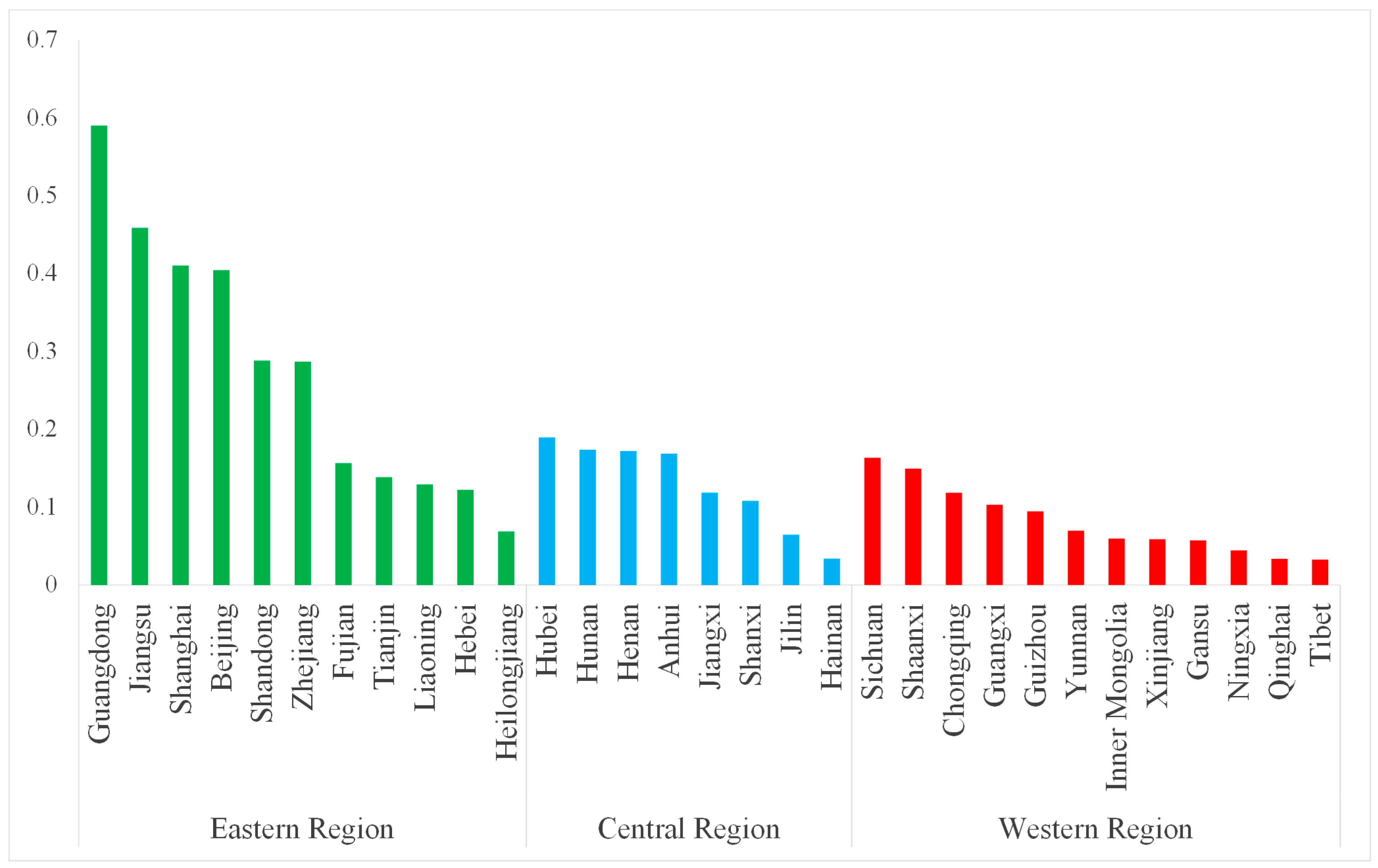

To further examine whether the digital economy has heterogeneous moderating effects on the path of promoting economic growth through exports in different regions, this paper divides 31 provinces in China into three categories, eastern, central, and western regions, as shown in Figure 2. Specifically, the eastern group consists of 11 provinces (e.g., Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Beijing, Shandong, Zhejiang, Fujian, Tianjin, Liaoning, Hebei, and Heilongjiang), which are colored in green; the central group consists of 8 provinces (e.g., Hubei, Hunan, Henan, Anhui, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Jilin, and Hainan), which are colored in blue; and the western group consists of 12 provinces (e.g., Sichuan, Shaanxi, Chongqing, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Tibet), which are colored in red [26].

Figure 2.

Digital economy index across 31 Chinese provinces in 2022.

Figure 2 illustrates the digital economy index across China’s 31 provinces in 2022. It is evident that eastern provinces such as Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shanghai, and Beijing lead in digital development, while central and western regions such as Hainan and Tibet lag significantly behind. This spatial disparity highlights the need to account for regional heterogeneity in our empirical analysis.

In each group, regression with or without control variables was conducted. Table 8 shows the regression results.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity analysis.

In the eastern region (Columns 1 and 2), the direct impact of exports (LNX) on regional economic growth was significantly positive both with and without control variables, with regression coefficients of 0.544 and 0.105, respectively, indicating that the driving effect of exports in the eastern region on economic growth was obvious. The coefficients of the interaction term (export × digital economy) are −0.572 and −0.154, both negative and significant when no variables are controlled. This indicates that in the eastern region, the higher the digital economic development level, the more significant the “inhibitory effect” it shows on the marginal effect of export-driven economic growth. This might stem from the fact that the digital economy in the eastern region is relatively mature. Some traditional export industries have transformed into high-value-added digital industries, and their marginal contribution to GDP may be relatively weakened.

In the central region (Columns 3 and 4), the impact of exports on GDP became insignificant after controlling for variables. The coefficients of the interaction terms were −0.180 and −0.221, indicating that the digital economy failed to effectively regulate the relationship between exports and economic growth in this region. This might be related to the relatively lagging construction of digital infrastructure in the central region and the digital economy’s limited integration with traditional export industries.

In the western region (Columns 5 and 6), the impact of exports on GDP remains positive and significant to a certain extent. However, the coefficients of the interaction terms are −0.294 and 0.197, with inconsistent directions and no significant impact. This indicates that in the western region, the digital economy has not yet exerted a stable moderating effect on the export-driven economic growth path. This might reflect that in the western regions, due to factors such as insufficient investment in digital resources and a single industrial structure, the digital economy has not yet truly been integrated into the traditional export mechanism.

Overall, the moderating effect of the digital economy on exports and economic growth shows significant regional heterogeneity. It only shows a significant negative moderating effect in the eastern region, and it is not significant in the central and western regions.

5. Discussion

The empirical analysis of this paper shows that exports remain an important driving force for regional economic growth in China. Under digital economy, the export-oriented development path has not yet failed, which is consistent with the expectations of traditional international trade theories. Especially for developing economies, exports are still playing a key role as an external demand engine. However, with the rapid development of the digital economy, exports’ growth effect has begun to be suppressed to a certain extent. Empirical results show that the digital economy level has a significant negative moderating effect on the path of export-driven economic growth, especially in the eastern region where the digital infrastructure is relatively complete and the industrial digitalization degree is relatively high. This discovery challenges the optimistic assumption in some of the literature about the “comprehensive positive empowerment of the digital economy”, suggesting that digital economy may break the path dependence of traditional industries in the short term, weaken the marginal dependence of some regions on foreign trade, and cause structural shocks. The observed negative moderating effect of the digital economy may reflect short-term structural frictions. While digital transformation can enhance productivity, it may also disrupt traditional export-oriented sectors, especially in regions where high-tech services and automation rapidly replace labor-intensive industries. In addition, the rise of digital platforms and cross-border e-commerce may lead to a technological substitution effect, whereby traditional trade intermediaries such as export agents and logistics firms lose their market share to more efficient digital alternatives. This can cause temporary dislocation in export channels and labor markets, especially in regions reliant on conventional trade models. Moreover, as highlighted by Syuntyurenko, the digital economy introduces opportunities and informational and structural risks, including uneven regional development and sectoral dislocation, which may temporarily weaken the traditional export–growth link before long-term gains materialize [27].

Furthermore, this paper finds that exports indirectly promote regional economic growth by facilitating R&D investment, confirming the existence of the “export–innovation–growth” path. Compared with existing studies, this paper verifies the direct economic effect of exports, identifies the role of R&D investment as a mediating variable in the mechanism, and expands the analytical perspective of the theory of foreign trade growth. A moderating effect is particularly prominent in the eastern region, while no obvious role is shown in the central and western regions. This indicates that the imbalance in regional development is not only reflected in the total economic volume, but also in the structural mechanism and policy response.

Although this paper constructs a multi-dimensional model and ensures the credibility of the conclusion through robustness tests, there are still some limitations. For instance, the digital economy level measurement is still relatively macroscopic and makes it difficult to reflect the digital economy process of micro-entities (such as enterprises). Meanwhile, the panel data is at the provincial level and fails to reveal more detailed mechanisms of interactions at the city or enterprise level. Future research can further integrate urban data or micro-data of enterprises or adopt dynamic panel models to explore the structural reconstruction effect of the digital economy on different types of export industries, especially whether low-value-added industries in manufacturing will be marginalized due to digitalization. In addition, policy variables can also be incorporated into the analytical framework to explore the mediating role of local governments in promoting digital infrastructure and facilitating export innovation, thereby providing more detailed and operational policy recommendations for emerging economies.

6. Policy Recommendations

Based on the empirical findings, this paper proposed several region-specific and mechanism-oriented policy recommendations: Firstly, strengthen the integration of exports with digital transformation. While exports remain a key driver of economic growth, their impact is increasingly moderated by digital development. Therefore, it is essential to upgrade export structures toward high-tech and high-value-added sectors. In regions with strong digital infrastructure (e.g., eastern provinces), policies should aim to mitigate the crowding-out effect of digitalization on labor-intensive industries by promoting digital trade platforms, intelligent logistics, and small- and medium-size enterprises’ digital capacity building. Secondly, promote differentiated digital infrastructure strategies. This study finds significant regional heterogeneity in digital economy development, which moderates the export–growth relationship. Eastern regions should focus on balancing digital innovation with traditional export competitiveness, while central and western regions should accelerate the construction of new digital infrastructure (e.g., 5G, AI applications, industrial internet) to close the digital gap and enhance export capacities. Thirdly, enhance R&D-driven export innovation. Given the confirmed mediating role of R&D investment, governments should improve R&D incentive mechanisms and strengthen support for technological innovation in export-oriented firms, especially small- and medium-size enterprises. This could include targeted subsidies, tax credits, and public–private partnerships to create a virtuous cycle from export-driven to innovation-driven and ultimately to high-quality economic growth. Finally, improve regional policy coordination and precision. The findings of this study show that “one-size-fits-all” strategies may not be effective in the digital context. Policymakers should take into account each region’s export dependence, industrial base, and digital readiness when designing digital-trade policy frameworks to ensure balanced regional development and sustainable export performance.

7. Conclusions

This paper systematically examines the impact of exports on regional economic growth. It further introduces the digital economy level as a moderating variable and incorporates R&D investment into the mechanism path to construct a multi-dimensional panel regression model. The empirical results show that exports have a significant positive promoting effect on regional economic growth. After controlling for variables such as employment scale and government expenditure, this impact remains robust, verifying the practical applicability of the export-oriented growth path at the current stage.

Further analysis reveals that the digital economy has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between exports and economic growth; that is, the development of the digital economy has weakened the growth-driving effect of exports to a certain extent. In the analysis of regional heterogeneity, this moderating effect only shows a significant negative effect in the eastern region, and it is not significant in the central and western regions. This indicates that the digital economy has formed a reconstructing effect on the traditional export model in more developed regions, but it has not yet demonstrated an effective moderating function in regions with a weaker digital foundation. In terms of mechanism analysis, R&D investment shows a partial mediating effect in the path by which exports affect economic growth, indicating that exports indirectly drive regional economic development by promoting technological innovation, reflecting the transmission mechanism among “export–innovation–growth”. Furthermore, through robustness tests such as lagging variables, control variable substitution, elimination of epidemic years, and extreme value processing, the regression results remained consistent all the time.

Unlike most previous studies that emphasize the uniformly positive role of the digital economy in promoting exports or innovation [1,2,3,4,5,7,9,28], our findings reveal significant regional heterogeneity, including a negative moderating effect of the digital economy in more developed eastern provinces. This suggests that while digital transformation may boost productivity, it can also disrupt traditional export channels through technological substitution, uneven regional capacities, and structural shifts. Therefore, differentiated digital trade strategies tailored to regional conditions are necessary. In addition, this study is based on macro-level provincial data, and thus does not capture micro-level heterogeneity across firms. As noted by Cui & Yang and Ding et al., firm-level digital transformation interacts with export performance through mechanisms such as supply chain resilience and export upgrading [5,9]. Future research could incorporate enterprise-level evidence or case studies to further verify and enrich the pathway of “digital empowerment of exports” and uncover firm-specific mechanisms.

In conclusion, this paper holds that exports remain a driving force for regional economic growth in China at present, but their effects are profoundly influenced by the trend of digital economy. In light of the characteristics of regional digital infrastructure and industrial structure, efforts should be made to promote the in-depth integration of the digital economy and export industries in a way that suits local conditions. In particular, in the central and western regions, efforts should be made to strengthen the construction of digital infrastructure and technological capabilities to promote coordinated regional development and high-quality economic growth. Furthermore, the transmission mechanism of “export–innovation–growth” and the regulatory path of the digital economy proposed in this paper also have certain implications for other developing countries in the stage of industrial transformation. Especially for countries with a high degree of export dependence and an incomplete digital infrastructure, coordinating the relationship between traditional trade and digital economy is a key issue for achieving sustainable growth. China’s experience can provide policy references and path lessons for such developing countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; Data curation, X.L.; Formal analysis, X.L.; Methodology, X.L.; Writing—original draft, X.L.; Supervision, R.A.; Visualization, N.D.; Writing—review and editing, X.L. and N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “2022 Young Innovative Talents Program of Guangdong Universities” under Grant No. 2022WQNCX086 and the “Project of Science and Technology of Guangdong Technology College” under Grant No. 2023YBSK047.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liang, S.; Tan, Q. Can the Digital Economy Accelerate China’s Export Technology Upgrading? Based on the Perspective of Export Technology Complexity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Sun, Y. Digital Economy, Employment Structure and Labor Share. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Said, R. The Effect of the Digital Economy on the Employment Structure in China. Economies 2023, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Digital Economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, J. The Effect of Digital Transformation on Export Upgrading: Firm-Level Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2025, 61, 3172–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; She, Q. The Impact of Corporate Digital Transformation on the Export Product Quality: Evidence from Chinese Enterprises. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Impact of Digital Economy on Inter-Regional Trade: An Empirical Analysis in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, J. China’s Green Digital Era: How Does Digital Economy Enable Green Economic Growth? Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Yang, W. The Digital Economy and the Resilience of Enterprise Exports: Supply Chain Stability as a Mediator. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 73, 106650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B. Exports, Policy Choices, and Economic Growth in Developing Countries after the 1973 Oil Shock. J. Dev. Econ. 1985, 18, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G. On Exports and Economic Growth. J. Dev. Econ. 1983, 12, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E.; Krugman, P. Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Awokuse, T.O. Trade Openness and Economic Growth: Is Growth Export-Led or Import-Led? Appl. Econ. 2008, 40, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R.; Hwang, J.; Rodrik, D. What You Export Matters. J. Econ. Growth 2007, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.B.; Jensen, J.B. Exceptional Exporter Performance: Cause, Effect, or Both? J. Int. Econ. 1999, 47, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olabisi, M. The Impact of Exporting and Foreign Direct Investment on Product Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturers. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2017, 35, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, X. The Impact of Internet on Innovation of Manufacturing Export Enterprises: Internal Mechanism and Micro Evidence. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J. The Impact of Digitalization on Technological Structure of China’s Exports: An Empirical Test Based on the Panel Threshold Effect Model. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 10004–10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhong, Q.; Lee, C.C. Digitalization, Competition Strategy and Corporate Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Listed Companies. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 82, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Howitt, P. A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction. Econometrica 1990, 60, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous Technological Change. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98 Pt 2, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, B.Y.; Roberts, M.J.; Xu, D.Y. R&D Investments, Exporting, and the Evolution of Firm Productivity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Melitz, M.J. The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica 2003, 71, 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Sun, Z.; Liu, H. Disentangling the Effects of Endogenous Export and Innovation on the Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Firms. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 50, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ding, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Analysis of Provincial Total-Factor Air Pollution Efficiency in China by Using Context-Dependent Slacks-Based Measure Considering Undesirable Outputs. Nat. Hazards 2020, 104, 1899–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syuntyurenko, O.V. The Risks of the Digital Economy: Information Aspects. Sci. Technol. Inf. Process. 2020, 47, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ma, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L. Research on the Influence Mechanism of the Digital Economy on Regional Sustainable Development. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 202, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).