Abstract

This study explores the migration intentions of university students—representing the potential creative class—in Erzurum, a medium-sized city in eastern Turkey experiencing shrinkage. Within the theoretical framework of shrinking cities, it investigates how economic, social, physical, and personal factors influence students’ post-graduation stay or leave decisions. Survey data from 742 Architecture and Fine Arts students at Atatürk University were analyzed using factor analysis, logistic regression, and correlation to identify key migration drivers. Findings reveal that, in addition to economic concerns such as limited job opportunities and low income, personal development opportunities and social engagement also play a decisive role. In particular, the perception of limited chances for skill enhancement and the belief that Erzurum is not a good place to meet people emerged as the strongest predictors of migration intentions. These results suggest that members of the creative class are influenced not only by economic incentives but also by broader urban experiences related to self-growth and social connectivity. This study highlights spatial inequalities in access to cultural, educational, and social infrastructure, raising important questions about spatial justice in shrinking urban contexts. This paper contributes to the literature on shrinking cities by highlighting creative youth in mid-sized Global South cities. It suggests smart shrinkage strategies focused on creative sector development, improved quality of life, and inclusive planning to retain young talent and support sustainable urban revitalization.

1. Introduction

Deindustrialization, globalization, and demographic transformations have led many cities to experience population decline and economic contraction. This phenomenon, widely referred to as “shrinking cities,” is largely driven by diminishing job opportunities, a stagnant social environment, and inadequate infrastructure—factors that contribute to the outmigration of young populations. Such processes complicate the prospects for sustainable urban development and deepen regional disparities over time.

With the rise of intercity competition under globalization, while some cities have emerged as attractive hubs, others have faced significant demographic losses. Traditional growth-oriented urban development models have proven inadequate for addressing the challenges of cities undergoing demographic shrinkage. Therefore, the emergence of alternative approaches—particularly smart shrinkage strategies tailored to such urban contexts—has gained growing academic attention.

The literature on shrinking cities has traditionally focused on post-industrial urbanization, economic decline, and spatial transformation of urban shrinkage [1,2]. These studies predominantly examine large metropolitan areas in Europe and North America, often portraying shrinkage as a crisis associated with deindustrialization, population loss, and social decline, leaving a significant gap regarding the role and migration tendencies of the creative class in small and medium-sized cities. As Florida [3] emphasized, the pivotal role of the creative class—defined as individuals engaged in knowledge-intensive, cultural, and innovative occupations—in driving economic growth and innovation is primarily examined in the context of growing and vibrant cities. However, as their residential and professional choices are starting to be seen as catalysts for economic growth and urban revitalization, a more nuanced understanding of their role in and impact on shrinking cities is emerging [4].

A significant gap remains in understanding the dynamics of the creative class within small and medium-sized shrinking cities, particularly in the Global South. Despite the emphasis on the central role of creative class on urban competitiveness [3], empirical research on their migration intentions (especially in demographically declining urban contexts), mobility patterns, place preferences, and the impact of this mobility on shaping urban development trajectories in the 21st century is still limited, which highlights the need to re-evaluate traditional urban development paradigms and explore adaptive strategies such as smart shrinkage.

Recent studies have begun to reframe urban shrinkage as a potential opportunity for rethinking urban development. Emerging studies highlight themes such as urban resilience, de-growth, adaptive reuse, post-pandemic spatial restructuring, inclusive governance, and creative economy strategies as alternative responses to decline [5,6,7,8,9,10]. In this evolving discourse, shrinking cities are no longer viewed solely as sites of failure but also as spaces for experimental and sustainable urban futures. Within this context, the present study contributes to the literature by exploring the migration intentions of the emerging creative class in a mid-sized shrinking city in Türkiye, thereby addressing a notable gap in both geographic and conceptual coverage.

Located in eastern Türkiye, Erzurum has historically served as a key regional administrative, educational, and cultural hub within the Eastern Anatolia Region. Despite its strategic location and the presence of two higher education institutions, the city has been experiencing steady population loss over the past two decades. National census data indicate that Erzurum’s population declined from approximately 785,000 in 2007 to around 750,000 in 2023 [11], primarily due to the outmigration of younger age groups. Once ranked among the 20 most populous cities in Türkiye, Erzurum has gradually lost its demographic weight, falling behind several mid-sized western cities in terms of population and economic dynamism. This demographic contraction has adversely impacted the city’s labor market, social vibrancy, and development prospects.

Although Erzurum continues to attract a significant student population, it struggles to retain its creative and educated youth after graduation. This trend further accelerates the city’s shrinkage, weakening its potential to sustain innovation, cultural vitality, and economic diversification. As current urban planning and development strategies have failed to reverse this outmigration trend, there is an urgent need for a new policy framework that places the creative class at the center of sustainable urban regeneration efforts.

Against this backdrop, the present study aims to analyze the economic, social, and physical factors that influence whether university students—representing Erzurum’s potential creative class—choose to remain in or leave the city. The central goal of the research is to identify the key parameters shaping the stay-or-leave decisions of Erzurum’s creative class and to propose strategic responses that can manage the city’s shrinkage process more effectively.

The research seeks to answer the following key questions:

- How do existing urban interventions in Erzurum (such as urban transformation, housing, and transportation policies) affect the migration preferences of the creative class?

- How do socio-cultural activities and overall urban quality of life shape the city’s image and influence young people’s decisions to stay?

- What strategic plans can be developed to enhance the likelihood that students from Erzurum’s creative class will remain in the city after graduation?

This study’s originality lies in its creative class perspective—an underexplored dimension in the shrinking cities literature—and its aim to develop applicable strategies to increase the urban retention of young, educated individuals. Moreover, the present study adopts a broadened interpretation of the notion of the ‘creative class’, encompassing not solely currently employed professionals but also university students engaged in training in creative disciplines, including Architecture, Urban Planning, Fine Arts, and Design. Despite the fact that these students may not yet be engaged in professional creative production, they demonstrate the educational orientation, skill development trajectory, and cultural capital that are typically associated with future participation in the creative economy. Consequently, the analysis of students’ future decisions regarding their continued residence in the city following graduation is intended to provide insight into their professional aspirations. The central inquiry pertains to the extent to which students aspiring to pursue careers in creative professions express a desire to reside in Erzurum in the future. This approach is consistent with Florida’s notion of the creative class [3] as comprising individuals involved in problem-solving, innovation, and artistic creation, even at early career stages. Thus, this group is regarded as a potential or emergent creative class, especially pertinent in the context of shrinking cities to maintain such talent and stimulate economic growth.

Accordingly, the research has two primary objectives:

- To identify the economic, social, and physical factors influencing the migration decisions of Erzurum’s creative class;

- To outline smart shrinkage strategies and performance indicators for evaluating their impact.

Ultimately, this study seeks to contribute to sustainable urban development approaches that move beyond traditional growth-centric planning models, by proposing adaptable and creative class-oriented strategies for cities experiencing shrinkage.

2. Theoretical Framework

Research on shrinking cities has primarily focused on the phenomenon of population decline and its socio-economic consequences. Earlier studies have examined the effects of deindustrialization, demographic shifts, and urban transformation policies mainly in the context European and North American cities [1,12,13,14,15]. These studies associated urban shrinkage commonly with economic stagnation, the downturn of industrial sectors, and population aging [1,15]. While these traditional theories view population decline and economic contraction as anomalies or failures of those cities, Xu et al. (2025) [7] illustrate how the growth of larger metropolitan areas can inadvertently contribute to the shrinkage of smaller and mid-sized cities within the same regional system, creating a complex interplay of forces that shape urban trajectories. These dynamics lead to structural changes in demographics and a significant decline in those cities’ economic vitality.

Recent discussions on shrinking cities have evolved beyond deficit-oriented frameworks to encompass broader concepts such as urban resilience, degrowth, adaptive transformation, inclusive governance, and responsive urban policy [5,6,7,8,9,10,16,17]. This emerging perspective views shrinkage as an opportunity to reimagine urban development through inclusive planning and creative economy strategies to improve urban quality of life and spatial justice, rather than merely treating it as a challenge. There is also increasing attention being paid to the spatial consequences of shrinkage, including issues such as the management of vacant land, the deterioration of infrastructure, and the decline in public services. Xie and Chen (2024) [16], for example, emphasize that the strategic planning and redevelopment of post-industrial land can reverse shrinkage trends. Such approaches are particularly relevant for cities burdened by outdated development models that are seeking to align their physical environments with new demographic and economic realities. Furthermore, the concept of urban resilience has gained traction, as demonstrated by studies such as those by Teller and Saarinen (2024) [8], which examine how post-industrial cities can enhance their ability to withstand and adapt to disruptions, including those resulting from climate change and economic shocks. Together, these studies emphasize the importance of adopting flexible and adaptive urban planning strategies to respond effectively to the multifaceted dynamics of urban shrinkage.

Due to the impact of the creative class to urban trajectories in the 21st century, pull and push factors driving creative youth migration remain a central focus. The outmigration of young populations is often explained by limited job opportunities, a lack of career development prospects, and poor urban quality of life [2,12,18]. While early literature emphasizes macro-economic restructuring, recent studies highlight the importance of localized strategies that enhance social cohesion, cultural vitality, and participation in urban governance, particularly in small and medium-sized cities of the Global South [5,7,10,17,19]. Urban planning strategies in shrinking cities are increasingly shifting from growth-oriented paradigms toward new models prioritizing social and economic sustainability, together with sustainable quality of life, creative sector engagement, and long-term urban resilience [20].

Identifying push and pull factors is crucial for understanding population mobility, i.e., why people choose to leave or stay in a particular city [21,22]. While early literature primarily examined the pull factors of global cities (diverse cultural amenities, tolerance, etc.), recent literature started to focus on the complexities of creative class mobility, their nuanced place selection criteria, and the implications for a broader range of urban contexts, including those experiencing population decline. However, studies directly addressing push–pull dynamics in the context of shrinking cities remain scarce. One of the few in-depth studies in this field is by Reckien and Martinez-Fernandez [23], which focuses on suburbanization trends. Overall, most research has dealt with push–pull factors in relation to disadvantaged areas or urban sprawl rather than shrinkage-specific contexts [24,25,26]. For example, while disadvantaged areas with poor quality of life often lead to outmigration, some shrinking cities may offer improved living conditions for the remaining residents [27].

Given their high mobility, young adults contribute significantly to accelerating population decline [20,28], and it was thought that cities offering higher levels of economic activity and more job opportunities tend to attract them [29,30]. However, migration decisions of the creative class extend beyond simple economic incentives but are affected by a new urban attractiveness perception defined by the interplay of quality of life, social networks, and perceived opportunities. Chen et al. (2025) [5] showed that creative individuals do not merely seek high paying jobs but also environments that foster well-being, social connection, and professional growth in their analysis on urban flows, including intercity migration. This aligns with findings that emphasize the importance of social capital and community engagement in retaining skilled populations [31]. Contemporary literature discusses the potential benefits of shrinking cities to offer lower living costs, increased personal space, and less competitive job environments, which may result in higher perceived quality of life for certain residents [27,32,33].

Thus, place selection for the creative class is a multifaceted decision influenced by a blend of economic, social, environmental, spatial, and functional factors [34]. While traditional economic indicators remain crucial, the availability of cultural amenities, spatial qualities—such as esthetics, accessibility, and green spaces—as well as social bonds and community belonging are recognized as equally vital [22,35]. Functional dimensions such as transportation, commerce, and healthcare services further contribute to residential satisfaction. Besides socio-economic and spatial factors, educational opportunities also influence migration behavior. Cities that host universities benefit from a temporary retention of student populations, but the limited post-graduation job prospects often drive these individuals toward larger urban centers [36,37].

Place attachment, or the emotional and social connection individuals establish with their environment, is another key determinant in migration decisions. Social networks and a sense of belonging can increase the likelihood of residents remaining in a city despite limited economic incentives [31,38,39]. However, place attachment should be understood in relation to economic factors. As Florida [3] emphasized, cities preferred by the creative class are not defined by economic conditions alone but also by cultural vibrancy, openness, and opportunities for social interaction. Yet, most of these studies focus on large metropolitan areas, leaving small and medium-sized cities underrepresented in the literature.

This issue is particularly relevant for cities that may not be competitive on a global economic scale but can offer a high quality of life and strong community ties. Located in eastern Turkey, Erzurum is among the medium-sized cities facing population decline, primarily due to the outmigration of young people after completing their education. Traditional growth-oriented urban development strategies have proven inadequate in reversing this trend. The present survey-based study aims to address this gap by examining the economic, social, and physical factors influencing the stay-or-leave decisions of university students—a key segment of the potential creative class—in Erzurum. By focusing on youth outmigration rather than deindustrialization, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on urban shrinkage, offering insights into how non-economic factors such as social networks and urban amenities interact with economic realities to shape the mobility patterns of the creative class.

Recognizing the multidimensionality of urban shrinkage, i.e., that it encompasses demographic, economic, social and spatial factors, Xing et al. (2025) [10] provide a framework for analyzing urban shrinkage. They highlight the interconnections between population decline, economic stagnation, social disengagement, and underutilized urban spaces. This integrated perspective is crucial for understanding cities such as Erzurum, where shrinkage is primarily driven by the emigration of young, educated individuals rather than a decline in traditional industries. Using questionnaire data, this study therefore examines the influence of economic, social, physical, and individual factors on the decision to stay or leave. The study provides a clearer understanding of the migration dynamics of the creative class in mid-sized cities such as Erzurum. Due to the scarcity of research on Turkey’s creative class, this study offers a unique regional perspective and will be a valuable reference for future studies on urban shrinkage and youth migration.

3. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted among students from the Faculty of Architecture and Design and the Faculty of Fine Arts at Atatürk University in Erzurum. A total of 742 students participated in the survey. The questionnaire was designed around themes such as participants’ demographic information, economic conditions, social life, physical environment, and individual preferences.

Survey data were analyzed using four main methods:

- Factor Analysis: Applied to group the variables influencing students’ decisions to stay in or leave the city and to identify the underlying components.

- Logistic Regression Analysis: Used to determine which factors most significantly influence the decision to stay in or leave Erzurum.

- Correlation Analysis: Conducted to measure the strength of the relationships among economic, social, physical, and personal factors.

- Descriptive Statistics: Used to provide an overview of respondents’ preferences and demographic distributions.

3.1. Data Collection

The target group of the survey consisted of university students aged 18 to 24, a demographic segment considered highly significant in terms of urban development and creative economies. Data collection was conducted through both face-to-face interviews and online forms, yielding responses from 742 participants. The sample size was determined to be representative of the creative class demographic at Atatürk University, and participation was voluntary. A random sampling method was employed to ensure diversity in socio-economic and academic backgrounds.

The questionnaire included items related to participants’ demographic and socio-economic characteristics, their lived experiences in Erzurum, their perceptions of the city, and their intentions to stay or leave. In addition, push and pull factors potentially influencing students’ migration decisions were identified and rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not important, 5 = very important).

The methodological framework of the study was developed with reference to previous research exploring migration and settlement decisions in the context of urban shrinkage, e.g., Refs. [23,35,40]. The survey addressed factors such as employment opportunities, housing costs, transportation infrastructure, social and cultural activities, safety, environmental quality, urban esthetics, and sense of community. It consisted of 46 pull and 47 push factors (see Table 1), allowing participants to assess how each influenced their willingness to stay in or leave the city.

Table 1.

Push and Pull Factors.

Before the full-scale application of the survey, a two-step validation process was undertaken to ensure both the clarity of the questions and the content validity of the measurement scales. First, the initial set of push and pull items was developed based on an extensive review of the literature on urban shrinkage, migration, and creative class mobility [3,22,23]. In addition to literature-based derivation, item generation was guided by established theoretical frameworks including push–pull migration theory, creative class theory, and residential satisfaction models. This alignment ensured that the scale captured both attitudinal and contextual dimensions relevant to the migration decisions of creative youth in shrinking urban settings.

Second, a pilot study was conducted with 20 students from urban planning departments to assess the clarity, thematic consistency, and interpretability of survey items. Feedback was also collected from four academic experts specializing in urban planning, local economic development, migration studies, and urban policy. Based on their recommendations, several items were revised for clarity, merged to avoid redundancy, or excluded due to thematic misalignment. The refined instrument was then finalized for full implementation.

The data collected through the finalized scale were subsequently analyzed using factor analysis, which identified the latent dimensions and most influential parameters shaping the stay-or-leave decisions of Erzurum’s creative class. This iterative design process enhanced the validity and reliability of the measurement tool and ensured alignment with both theoretical expectations and contextual realities.

3.2. Data Analysis

To analyze the data collected through the survey, statistical methods such as factor analysis and regression modeling were employed. Initially, the suitability of the dataset—collected to identify the economic, social, and physical factors influencing the creative class’s tendency to stay in or leave Erzurum—was assessed.

Push and pull factors included in the questionnaire were evaluated by participants using a 5-point Likert scale. Before conducting factor analysis, the appropriateness of the data was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. The KMO values exceeded 0.8, indicating that the sample was adequate for conducting factor analysis. Bartlett’s test confirmed the presence of significant correlations among the variables, supporting the use of factor analysis (p < 0.05).

To assess the reliability of the factor structure, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients were calculated. The high reliability coefficients indicated a strong internal consistency among the survey items and confirmed the robustness of the factor analysis results (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The Results for The Pull and Push Factor Tests.

The aforementioned values confirmed that the sample size was adequate for factor analysis and that there were meaningful correlations among the variables.

Subsequently, factor analysis was conducted to identify latent variables that could account for the variance among a large set of observed variables. The objective of this analysis was to determine whether the variables related to migration decisions—categorized as push and pull factors—could be meaningfully grouped into a smaller number of interpretable dimensions. This method allowed for the identification of clusters based on inter-item correlations.

Exploratory factor analysis yielded six principal components for pull factors and five for push factors. The underlying dimensions and the number of associated variables for each were as follows:

Pull Factors:

- Built Environment Conditions (13 items);

- Economic Opportunities (7 items);

- Personal Attributes (8 items);

- Cultural and Recreational Activities (3 items);

- Social Cohesion (10 items);

- Accessibility (5 items).

Push Factors:

- Built Environment Challenges (16 items);

- Economic Hardships (8 items);

- Social Challenges (9 items);

- Personal Constraints (11 items);

- Cultural Limitations (3 items).

The Pattern Matrix values provided in Table 3 and Table 4 indicate the extent to which each item loads onto its respective latent factor, and also reflect the strength of its contribution to the decision to stay in or leave Erzurum.

Table 3.

Identified Pull Factor Dimensions and Associated Pattern Matrix.

Table 4.

Identified Push Factor Dimensions and Associated Pattern Matrix.

Upon reviewing the Pattern Matrix for pull factors (46 items), six distinct subscales emerged: Items with high loadings on the first factor are primarily related to Built Environment Conditions. The second factor is dominated by items concerning Economic Opportunities. The third factor reflects Personal Attributes, while the fourth focuses on Cultural and Recreational Activities. The fifth factor pertains to Social Cohesion, and the sixth encompasses aspects of Accessibility.

Likewise, for the push factors (47 items), the analysis identified five subscales: the first factor relates to Built Environment Challenges, the second to Economic Hardships, the third to Social Challenges, the fourth to Personal Constraints, and the fifth to Cultural Limitations. Variables under the ‘Accessibility’ heading were not included in the explanatory group as push factors and were not evaluated as determinants of migration from the city.

These results highlight the multidimensional structure of the factors influencing migration intentions and demonstrate the explanatory power of the factor groupings in the context of shrinking cities.

In the next phase of the study, correlation analysis was conducted to understand the relationships between the principal factors. To interpret which variables had a stronger effect on the decision to stay or leave, the Pattern Matrix values presented in Table 2 and Table 3 were referenced.

Correlation analysis measures whether two variables change together, that is, the direction and strength of the relationship. In this case, the analysis focused on the correlation between the identified push and pull factors and their impact on the migration intentions of participants. The factor structures defined in Table 2 and Table 3 were examined in relation to stay-or-leave decisions.

Table 5 and Table 6 present the results of this analysis. Each principal component included in these tables represents the mean of its associated sub-variables identified in Table 3 and Table 4. In this way, all variables were represented equally within the correlation analysis framework.

Table 5.

Correlation Matrix of Principal Pull Factors.

Table 6.

Correlation Matrix of Principal Push Factors.

Subsequently, logistic regression analysis was employed to assess the predictive power of independent variables on the dependent variable, i.e., the decision to stay in or leave the city. This method was used to identify which variables significantly influence whether members of the creative class are likely to remain in or migrate from a shrinking city like Erzurum. In the regression model for outmigration, the analysis explored which factors increased or decreased the probability of students leaving Erzurum. In contrast, the regression model for the decision to stay identified the factors that positively contributed to the likelihood of students remaining in the city.

4. Findings

The survey was conducted with students from the departments of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Urban and Regional Planning, and Interior Architecture in the Faculty of Architecture and Design, and from departments such as Painting, Photography, Traditional Turkish Arts, Graphic Arts, Sculpture, Musicology, Performing Arts, Ceramics, Textile and Fashion Design, and the Turkish Music State Conservatory in the Faculty of Fine Arts. Most of the participants were in their first or second year; however, the fourth-year students represent a key group in identifying post-graduation preferences. Female students outnumbered male participants.

In terms of birthplace, Erzurum had the highest share among respondents, followed by cities such as Trabzon, Istanbul, Ağrı, and Kars. Although most participants currently reside in Erzurum, others reported living in cities like Trabzon, Istanbul, Ağrı, Kars, and Samsun.

The most striking result of the survey relates to the preferences for staying in or leaving Erzurum. Of the participants, 76.7% responded, ‘I am considering leaving,’ indicating young people’s hesitation regarding long-term future planning in Erzurum. Those who were undecided constituted 2.2%, while 21.2% stated, ‘I am considering staying,’ reflecting a more positive perspective toward living in Erzurum.

Among economic factors, unemployment and low wages emerged as the most frequently cited drivers of outmigration. Limited job opportunities, particularly in creative sectors, present a serious issue for students aiming to pursue careers in these fields. Difficulties in acquiring real estate, low income levels, and high rent prices negatively influence long-term settlement decisions. The lack of sufficient entrepreneurial support also prevents the creative class from establishing their own businesses.

In the social dimension, the inadequacy of cultural and social activities was one of the most common complaints. A limited social environment contributes to social isolation. For female students in particular, perceived safety is a significant concern, and those with safety concerns are more inclined to prefer larger urban centers.

Insufficient transportation infrastructure restricts students’ intra-urban mobility. The lack of recreational spaces limits their social lives and diminishes leisure-time productivity. Environmental issues such as air pollution, poor architectural esthetics, and urban disorganization also negatively deter individuals from remaining in Erzurum.

Limited personal development opportunities make it difficult for the creative class to stay in the city. For students born and raised in Erzurum, family ties emerge as an important reason for staying. A sense of community attachment also significantly influences migration decisions.

In addition to general findings, correlation analysis was performed to better understand the relationships between principal variables. The results showed a positive relationship between all major variables and the tendency to stay or leave. Among these, “personal attributes” appeared as the most influential variable in determining whether the creative workforce would stay in Erzurum. The most significant sub-factors included mutual support among neighbors and a sense of community. Other key variables that promoted staying—ranked by influence—were Accessibility, Built Environment Conditions, Cultural and Recreational Opportunities, Social Cohesion, and Economic Opportunities.

With respect to push factors, the most influential variables in the decision to leave Erzurum were Built Environment Challenges, Economic Hardships, Personal Barriers, and Cultural/Sports Limitations

Social Challenges, on the other hand, were found to have little to no effect. Sub-variables under social challenges—such as political/religious pressure or discrimination—were not perceived as problematic. Similarly, urban safety and population density were not seen as current or anticipated concerns by the participants.

Among push factors, economic hardships were found to be the most influential in prompting outmigration, even though they were not the most decisive in stay decisions. The possibility of low income emerged as the strongest variable influencing the decision to leave. Other major factors included poor working conditions and unemployment, while difficulty acquiring real estate was the least impactful economic variable in leaving decisions.

In third place among the most influential push categories was built environment challenges, where poor environmental quality, accessibility problems, and dilapidated neighborhoods ranked highest. Other influential factors included dirty streets, depleting natural resources, harsh climate, lack of green spaces, and natural disaster risks.

The final stage of the study involved logistic regression analysis to examine which factors most strongly influenced students’ decisions to stay in or migrate from Erzurum after graduation. The model, validated through cross-validation, achieved a high prediction accuracy of 91.9%.

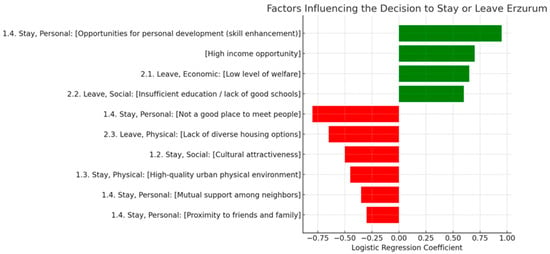

In this model, broader thematic categories were used instead of individual-level variables. The most influential factors determining whether students would stay or leave Erzurum were identified. As illustrated in Figure 1, green bars indicate factors that increase the likelihood of staying, while red bars represent those that increase the tendency to leave. The x-axis reflects logistic regression coefficients, with positive coefficients indicating retention factors and negative coefficients indicating migration drivers.

Figure 1.

Key Factors Influencing the Decision to Stay in or Leave Erzurum. Note: Green bars indicate factors positively associated with the decision to stay, while red bars indicate factors positively associated with the decision to leave. Logistic regression coefficients are shown on the x-axis.

Among the variables affecting the decision to leave Erzurum, economic and employment-related factors, social and cultural conditions, and psychological and individual motivations emerge as the most prominent drivers. In terms of economic and employment dimensions, limited job opportunities following graduation significantly decrease the likelihood of individuals remaining in Erzurum. Additionally, low wages and financial insecurity lead many to prefer cities that offer better economic prospects. The lack of career advancement opportunities further reinforces the decision to migrate.

As illustrated in Figure 1, two variables exhibit the largest absolute regression coefficients: “limited opportunities for skill enhancement” (–1.4) and “not a good place to meet people” (+1.4). These findings suggest that the migration intentions of creative youth are not shaped solely by economic or employment considerations, but also by perceptions of personal growth and social connectivity. Students who believe that Erzurum lacks adequate platforms for developing their skills—such as training, mentorship, or exposure to creative networks—are significantly more likely to leave. Similarly, the perception that the city does not offer a vibrant or welcoming social environment contributes strongly to the intention to migrate. These two dimensions—self-development and meaningful social interaction—are well-aligned with the core expectations of the creative class, who prioritize environments that support expression, autonomy, and community belonging. These results reinforce the importance of expanding not only job opportunities, but also social and cultural infrastructure as part of any retention strategy.

From a social and cultural perspective, limited social life, a lack of cultural events, and inadequate entertainment options serve as critical push factors directing individuals toward larger urban centers. Similarly, the shortage of recreational and leisure opportunities amplifies the tendency to leave. Psychological and individual factors—such as the perceived lack of long-term prospects in Erzurum and anxieties about the future—further increase the likelihood of migration. Moreover, the desire to establish an independent life and explore new experiences in other cities supports this tendency.

In contrast, the decision to remain in Erzurum is primarily influenced by family and social support, cost of living and comfort, and security and stability. Under family and social support, the presence of family members and close social networks within Erzurum is identified as one of the strongest motivators for staying. Individuals with well-established social ties in the city are more inclined to remain. Marital status also plays a role, with married individuals exhibiting a stronger tendency to stay.

With respect to cost of living and comfort, lower rent and living expenses compared to larger cities represent significant advantages supporting urban retention. Furthermore, convenient access to healthcare services enhances the appeal of continuing to live in Erzurum. Regarding safety and stability, the perception that Erzurum offers a more secure living environment than major metropolitan areas supports the intention to stay. The stressful lifestyle and intense competition commonly associated with larger cities make Erzurum an attractive alternative for those seeking a more stable and manageable living experience.

The analysis clearly reveals that economic constraints are the most decisive factor in the decision to leave Erzurum. Limited employment opportunities and unmet economic expectations substantially increase the probability of outmigration. Conversely, family and social ties are stronger determinants in the decision to stay, often surpassing economic motivations. The belief that Erzurum provides a safer and more stable environment compared to large urban areas also contributes significantly to individuals’ willingness to remain in the city.

Although the core logistic regression model in this study focuses on attitudinal factors such as economic, social, physical, and personal dimensions influencing the stay-or-leave decision, demographic variables also provide valuable insight into migration tendencies. To complement the main findings, we additionally examined how individual characteristics—specifically age, gender, academic discipline, and family residence—are associated with students’ intentions to stay in or leave Erzurum after graduation.

Among these attributes, academic discipline emerges as a particularly salient variable. Students enrolled in applied creative fields such as Architecture, Urban Planning, and Graphic Design demonstrated a notably higher inclination to leave Erzurum after graduation compared to those in fine arts or traditional arts programs. This differentiation likely stems from perceived mismatches between the urban environment and the professional opportunities associated with each discipline. For instance, students in design-intensive fields often expressed concerns over limited sector-specific employment opportunities, entrepreneurial infrastructure, and exposure to contemporary design culture—factors more readily accessible in metropolitan areas.

Furthermore, gender was observed to be modestly associated with stay intentions. Female students exhibited a slightly higher tendency to consider migration, often citing concerns related to personal safety, limited social freedom, and restricted access to inclusive public spaces. These findings align with prior research emphasizing the intersection between gendered perceptions of urban security and mobility preferences.

Regarding age, no significant differences were observed across cohorts, as the survey sample largely consisted of students aged between 18 and 24. However, family residence—whether students were originally from Erzurum or elsewhere—was a meaningful indicator. Participants who were born or raised in Erzurum reported higher levels of emotional attachment and were more likely to consider staying, particularly due to proximity to family and social networks.

While these demographic variables were not included in the main regression model to preserve its thematic focus on attitudinal constructs, the supplementary analysis confirms that demographic background complements attitudinal drivers and contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of migration behavior among the creative youth.

This layered approach supports the study’s conceptualization of the creative class as a heterogeneous group, whose mobility is shaped not only by urban quality of life and economic opportunities, but also by identity-related factors and professional orientation. These insights underscore the importance of designing retention strategies that account for both perceptual and demographic dimensions of the creative youth.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal significant intersections with the literature on urban planning and development, particularly within the framework of shrinking cities. Most cities experiencing population loss are transforming into outmigration regions due to declining economic opportunities, demographic shifts, and spatial transformations. In the case of Erzurum, the migration or retention tendencies of the creative class were examined, and the results were found to be consistent with the major migration drivers identified in the literature. However, this study offers original insights for cities like Erzurum, which are undergoing shrinkage not due to large-scale industrial loss, but rather due to youth outmigration.

Studies on shrinking cities often emphasize that economic opportunities are the most critical determinants of migration decisions [8,40]. Similarly, in this study, high income opportunities, employment in creative sectors, and the level of economic welfare were identified as the most important factors encouraging the creative class to stay in Erzurum. In contrast, unemployment, low income levels, and poor working conditions emerged as the strongest push factors encouraging individuals to leave. These findings highlight the need for shrinking cities to develop economic models that support creative and highly skilled human capital, rather than relying solely on traditional growth policies aimed at increasing population.

The existing literature primarily focuses on cities that shrink due to deindustrialization and suburbanization [2,23]. Erzurum differs from these cases in that its shrinkage is not a result of industrial decline, but rather of the departure of a young, educated population following graduation. This distinction underscores the need for policy proposals in Erzurum to place greater emphasis on socio-cultural and spatial factors.

The results of this study demonstrate that economic factors are the most dominant element influencing individuals’ migration decisions. A large proportion of students in Erzurum tend to leave the city in search of better job opportunities, higher income, and improved living standards. These findings are consistent with studies conducted in Europe and North America. For example, a study on Portuguese cities showed that employment in the industrial and service sectors contributed to population growth, while high unemployment accelerated population decline [41].

Furthermore, economic pull factors have a particularly strong influence on young people. The commitment of the creative class to a city is largely shaped by economic opportunities. This was also emphasized in a study on Barcelona, which showed a direct relationship between urban growth and employment opportunities in creative sectors [22]. However, the limited employment capacity of creative sectors in Erzurum increases the likelihood that individuals seeking such careers will leave the city. Therefore, enhancing incentives for creative industries in Erzurum could strengthen urban attachment.

In addition to economic factors, the findings also indicate that social ties have a greater influence on migration decisions than previously assumed. The literature notes that urban shrinkage can sometimes improve quality of life and create better spatial opportunities for the remaining population [27]. In Erzurum, clean air, green spaces, walking trails, and recreational amenities were identified as attractive factors encouraging individuals to stay. This aligns with research highlighting the influence of urban quality of life and the physical environment on population movements [42]. However, the lack of green space, prevalence of urban decay, and unplanned urbanization in Erzurum reduce urban quality of life and contribute to migration trends. The city’s harsh climate and inadequate infrastructure are considered significant push factors, although it should be noted that the physical environment exerts a more indirect influence on long-term settlement decisions than it does as a direct cause of migration. The distribution of economic and social resources across the city is not uniform, and there is a paucity of accessible and vibrant public spaces. It may thus be concluded that outmigration is not merely an economic or individual choice, but also a reflection of spatial injustices embedded in urban development patterns.

Social ties and sense of community have also been identified as significant determinants in the decision to stay or leave a city. The literature suggests that place attachment can delay or reduce migration in shrinking cities [31,39]. The survey conducted in Erzurum supports this conclusion, showing that proximity to family and friends is a strong factor encouraging individuals to remain. However, feelings of loneliness, lack of social support, and insufficient socio-cultural events in the city increase the likelihood of outmigration. This suggests that social ties alone are insufficient to prevent migration unless accompanied by economic security.

Proximity to family and friends enhances the tendency to stay when economic opportunities are adequate. Thus, social factors act more as complementary elements that delay or prevent migration when combined with economic security. This finding is consistent with previous research; cities with strong social networks and economic incentives are more likely to retain their residents.

In addition, the limited cultural and social opportunities in Erzurum weaken students’ sense of belonging to the city. This supports previous research indicating that a city’s socio-cultural appeal is a decisive factor in migration decisions [3]. However, logistic regression analysis shows that social ties, when combined with economic opportunities, strongly support the decision to stay in Erzurum.

Expanding cultural activities and diversifying art, entertainment, and social programs could increase individuals’ long-term retention in the city. Cultural opportunities are known to be essential for increasing the attractiveness of cities, especially for the creative class. In this respect, cultural development in Erzurum could not only reduce migration but also create new job opportunities.

Within the literature on shrinking cities, studies exploring how local identity and urban prestige influence stay decisions tend to focus on cities with historical and cultural heritage [33]. In Erzurum, urban prestige and cultural heritage play a role in the decision to stay, though their impact is not as strong as economic factors. This underscores the need to strengthen Erzurum’s socio-cultural attractiveness by supporting creative industries and diversifying cultural events.

This study contributes to the literature on shrinking cities in two fundamental ways. First, while most shrinking cities are associated with deindustrialization, Erzurum provides a new perspective by representing the shrinking of cities due to higher education-related youth migration. Second, the findings highlight the necessity of urban development models that focus on the creative class and strengthening social ties, rather than traditional growth-oriented policies. Moreover, Erzurum’s situation parallels that of shrinking cities in Western Europe and the U.S., where unemployment, stagnant housing markets, and limited economic opportunities encourage outmigration [27]. Unlike Western cases where aging populations and natural decline are dominant causes, in Erzurum the departure of young people is the primary driver. This shows that Erzurum’s population loss is not solely driven by natural demographic dynamics, but rather by economic conditions and urban opportunities [41].

In conclusion, policies promoting economic diversification, environmental sustainability, and social cohesion are essential for retaining the creative class in Erzurum. Expanding job opportunities, improving quality of life, and upgrading urban infrastructure emerge as key factors in mitigating population decline. The preferences expressed by university students underscore the importance of aligning urban policies with the expectations of young and educated residents. These results suggest that efforts to reverse outmigration must extend beyond physical improvements and address the broader socio-economic landscape. In particular, fostering a sense of community, ensuring cultural vibrancy, and providing stable career prospects are critical to encouraging long-term urban retention.

In light of these findings, the concept of smart shrinkage offers a relevant and strategic policy framework. Rather than pursuing traditional growth-oriented models, cities like Erzurum can benefit from embracing adaptive and sustainable approaches to urban decline. The smart shrinkage paradigm emphasizes proactive planning, efficient resource management, and improvements in residents’ quality of life [4]. Improvements to the city’s physical and social infrastructure, expansion of employment opportunities, and implementation of social policies that foster community ties are among the most effective strategies for encouraging members of the emerging creative class to remain in Erzurum. As Kiviaho and Toivonen (2023) [9] argue, scenario planning and contextual foresight are crucial in navigating the complex futures of shrinking cities. Moreover, Sandmann et al. (2025) [19] stress the importance of participatory governance and bottom–up initiatives in urban regeneration. These perspectives collectively underscore the relevance of smart shrinkage as a transformative framework for cities like Erzurum, where demographic decline can be met not with retreat, but rather through a strategic approach to reimagine urban futures through resilient, inclusive, flexible, and localized strategies/governance.

This study, conducted to understand the migration and retention tendencies among university students in Erzurum, provides a new perspective to the literature on shrinking cities by offering insights into the aspirations and retention preferences of young people in a shrinking context. While many theories exist on urban growth and decline, our findings highlight the combined role of social ties and economic opportunities in shaping stay decisions. Furthermore, it can be concluded that improvements in the urban environment can only contribute to long-term population stability when accompanied by economic prosperity.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study aimed to analyze the tendencies of individuals forming Erzurum’s creative class to either stay in or migrate from the city, and to offer policy suggestions in terms of urban planning and economic incentives. The survey and analytical findings revealed the primary factors that encourage staying in the city or increase the tendency to migrate. The results indicate that limited economic opportunities, restricted social life, insufficient physical environment, and lack of personal development opportunities are influential in the decisions of young and educated individuals to leave the city.

Logistic regression analysis shows that economic factors are the strongest determinants in migration decisions. While high income opportunities and employment options increase the tendency to stay in Erzurum, low welfare levels, limited career opportunities, and insufficient economic incentives are the most important factors triggering outmigration. Therefore, in order to retain Erzurum’s creative class, it is necessary to increase economic incentives and expand employment opportunities.

To enhance economic attractiveness, new employment opportunities targeting the creative sectors should be developed, incentive mechanisms supporting entrepreneurship should be established, and public–private sector cooperation should be strengthened. Implementing projects to create jobs for new graduates in Erzurum and supporting remote-working and digital economy-oriented initiatives will mitigate geographical disadvantages.

To revitalize social and cultural life, art festivals, cultural events, and student-oriented activities should be diversified, encouraging individuals to establish socio-cultural connections within the city. Security for female students and young professionals should be particularly enhanced through improvements in lighting, surveillance systems, and public transport safety.

Regarding improvements in physical and urban infrastructure, the university surroundings and city center should be transformed into attractive spaces supporting creative sectors. Public green spaces, parks, and recreational areas should be expanded, creating more social venues for youth. Strengthening transportation infrastructure will also facilitate young residents’ mobility within the city.

To improve personal development and educational opportunities, career centers for university graduates should be actively promoted, and employment processes should be supported. Programs for developing digital skills and creative industries training should be expanded to help individuals achieve their career goals. Mentorship and incubation centers should be established to foster student participation in the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The results of this study contribute to urban planning and urban economics disciplines by highlighting that traditional growth-oriented urban planning approaches are inadequate for shrinking cities [4]. Instead, “smart shrinkage” strategies should be developed. Specifically, for Erzurum, the following recommendations stand out:

- Economic attractiveness should be enhanced by creating additional employment opportunities in creative sectors and providing economic incentives to retain new graduates.

- Urban infrastructure improvements in transportation, housing, and recreational spaces will strengthen student attachment to the city [42,43]. Urban designs adaptive to Erzurum’s climate conditions should also be developed.

- The city’s attractiveness should be increased by diversifying social activities, artistic events, and cultural spaces.

- Local governance strategies should be reassessed to improve the quality of life in the city center, thus encouraging young people to remain in the city [44].

Overall, this study emphasizes the need for a multifaceted approach encompassing economic incentives, policies that foster social life, and the enhancement of urban infrastructure to ensure the retention of Erzurum’s creative and educated population. The observed patterns of outmigration among the city’s creative youth are indicative of underlying spatial inequalities and also reflect unmet needs in terms of personal development and social integration—two dimensions that strongly influence migration intentions according to the analysis. These findings underline the importance of recognizing that the decision to stay or leave is not solely determined by economic considerations, but by a broader urban experience shaped by creative potential, autonomy, and a sense of belonging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D. (Doğan Dursun) and D.D. (Defne Dursun); methodology, D.D. (Doğan Dursun); software, D.D. (Defne Dursun); validation, D.D. (Doğan Dursun) and D.D. (Defne Dursun) formal analysis, D.D. (Doğan Dursun); investigation, D.D. (Doğan Dursun); resources, D.D. (Doğan Dursun) and D.D. (Defne Dursun); data curation, D.D. (Doğan Dursun) and D.D. (Defne Dursun); writing—original draft preparation, D.D. (Doğan Dursun) and D.D. (Defne Dursun); writing—review and editing, D.D. (Defne Dursun); visualization, D.D. (Defne Dursun); supervision, D.D. (Defne Dursun); project administration, D.D. (Doğan Dursun); funding acquisition, D.D. (Doğan Dursun). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Atatürk University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit under the project titled “Potansiyel yaratıcı sınıfın nüfusu azalan büzüşen bir kent olan Erzurumdan gitme ve kalma tercihlerini etkileyen faktörlerin belirlenmesi” (Determining the factors influencing the stay-or-leave preferences of the potential creative class in Erzurum, a shrinking city experiencing population decline)—Project ID: 13118, Project Code: FBA-2023-13118. It was funded as a Basic Research Project (Temel Araştırma Projesi).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Science and Engineering of Atatürk University (protocol code E-60665420-000-2300281211/5/19 and date of approval 12 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Oswalt, P.; Rieniets, T. Atlas of Shrinking Cities; Hatje Cantz Publishers: Ostfildern, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2013, 20, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.J. Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tao, R.; Ma, Q. Rethinking shrinking cities through urban flows: Network-based insights into coordinated development. Urban Inform. 2025, 4, 14. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44212-025-00078-8 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hermans, M.; de Kraker, J.; Scholl, C. The Shrinking City as a Testing Ground for Urban Degrowth Practices. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, J.; Sho, K.; Seta, F. Urban Growth Divides: The inevitable structure of shrinking cities in urbanization evolution. Cities 2025, 158, 105638. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275124008527 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Teller, J.; Saarinen, J. Urban Resilience in Post-industrial Urban Landscapes: Necessity or Destiny? In The Reimagining of Urban Spaces; Lakušić, J., Pavičić, S., Stojčić, J., Scholten, N., van Sinderen Law, P.W.A., Eds.; Applied Innovation and Technology Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviaho, A.; Toivonen, S. Reimagining Alternative Future Development Trajectories of Shrinking Finnish Cities. International Planning Studies. 2023. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13563475.2023.2259109 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Xing, G.; Wang, D.; Cai, W. Study on multidimensional shrinkage spatial-temporal patterns and driving forces of cities in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22934. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-06292-3 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. The Results of Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS), as of 31 December 2023. 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=The-Results-of-Address-Based-Population-Registration-System-2023-49685 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rınk, D.; Haase, A.; Grossmann, K.; Couch, C.; Cocks, M. From Long-Term Shrinkage to Re-Growth? The Urban Development Trajectories of Liverpool and Leipzig. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 162–178. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23799118 (accessed on 10 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K. Viewpoint: The planning research agenda: Shrinking cities—A challenge for planning cultures. Town Plan. Rev. 2010, 81, i–vi. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27975967 (accessed on 3 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Turok, I.; Mykhnenko, V. The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities 2007, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, Y. Examining the Transformation of Postindustrial Land in Reversing the Trend of Urban Shrinkage. ScienceDirect. 2024. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844024036983 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Gu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhao, J.; Fei, T.; Ouyang, S. Examining the transformation of postindustrial land in reversing the lack of urban vitality: A paradigm spanning top-down and bottom-up approaches in urban planning studies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, T.; Pallagst, K.M. Urban shrinkage in Germany and the USA: A Comparison of Transformation Patterns and Local Strategies. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, L.; Gunko, M.; Shirobokova, I.; Adams, R.M.; Lilius, J.; Grossmann, K. Local Initiatives in Shrinking Cities: On Normative Framings and Hidden Aspirations in Scholarly Work. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2025, 49, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekveld, J.J. Understanding shrinkage in European regions. Erdkunde 2014, 68, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, P.; Magrini, S. Population growth in European cities: Weather matters—But only nationally. Reg. Stud. 2006, 40, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royuela, V.; Moreno, R.; Vaya, E. Influence of quality of life on urban growth. Reg. Stud. 2010, 44, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. The rise of urban shrinkage in Europe: Current research and future perspectives. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H.S. Excluded places: The interaction between segregation, urban decay and deprived neighbourhoods. Hous. Theory Soc. 2002, 19, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasius, J.; Friedrichs, J. Internal heterogeneity of deprivation among poor neighbourhoods in a very affluent region: The case of Hamburg. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 2237–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Karecha, J. Controlling urban sprawl: Some experiences from Liverpool. Cities 2006, 23, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B. Can a City Successfully Shrink? Evidence from Survey Data on Neighborhood Quality. Urban Aff. Rev. 2011, 47, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, K. European Migration: What Do We Know? Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnott, R.; Chaves, E.J. Commuting, congestion, and land use in an urban general equilibrium model. J. Public Econ. 2012, 96, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, W. The end of world population growth. Nature 2001, 412, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.B.; Perkins, D.D.; Brown, G. Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.; Pallagst, K.; Schwarz, T.; Popper, F. Planning Shrinking Cities. Prog. Plan. 2009, 72, 223–232. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1616130 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Delken, E. Happiness in shrinking cities in Germany: A research note. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellander, C.; Florida, R.; Stolarick, K. Here to stay: The effects of community satisfaction on the decision to stay. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2011, 6, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Fornara, F.; Bonnes, M. Perceived residential environment quality in middle- and low-extension Italian cities. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 56, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, E.J.; Cho, S.; Reback, R. Mobility, housing markets, and schools: Estimating the effects of inter-district choice programs. J. Public Econ. 2012, 96, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Ali, K.; Olfert, M.R.; Partridge, M.D. Voting with their feet: Jobs versus amenities. Growth Change 2007, 38, 77–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulton, C.; Theodos, B.; Turner, M.A. Residential mobility and neighborhood change: Real neighborhoods under the microscope. Cityscape 2012, 14, 55–89. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/cityscpe/vol14num3/article3.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Andersen, H.S.; van Kempen, R. New trends in urban policies in Europe: Evidence from the Netherlands and Denmark. Cities 2003, 20, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.H.; Nunes, L.C.; Barreira, A.P. Urban shrinkage: A multidimensional approach to European cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1326–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Ballas, D. What makes a ‘happy city’? Cities 2013, 32, S39–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger-Ross, C.L.; Uzzell, D.L. Place and identity processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amérigo, M.; Aragonés, J.I. A theoretical and methodological approach to the study of residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).