1. Introduction

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent an ambitious and comprehensive framework aimed at addressing the world’s most pressing social, economic, and environmental challenges [

1,

2]. Adopted in 2015 by all 193 member states, these 17 goals are designed to create a more inclusive, sustainable, and equitable global society by 2030 [

3,

4,

5]. However, “pragmatic sustainability” that bridges the gap between ideal sustainable futures and the messy, constrained realities of policymaking and societal change, should be the future focus of our modern society and the ultimate goal of all SDGs [

6]. Each goal tackles a specific area of concern, with SDG12 focusing specifically on “responsible consumption and production” [

7]. As one of the critical pillars for sustainable development, SDG12 seeks to ensure that economic growth aligns with the planet’s ecological limits by promoting sustainable consumption, improving resource efficiency, reducing waste, and encouraging businesses and governments to adopt environmentally responsible practices [

5,

8].

The importance of SDG12 has grown significantly in the face of intensifying global environmental degradation, driven by unsustainable consumption patterns and resource extraction. From rising greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation to increased pollution and the depletion of natural resources, the world faces unprecedented environmental challenges that demand urgent and comprehensive action [

9,

10]. Achieving SDG12 is integral not only for environmental sustainability but also for economic resilience and social equity [

4]. Governments, businesses, and civil society must collectively transform their practices to reduce the negative environmental impact of consumption and production patterns, making SDG12 central to global efforts to combat climate change and create a sustainable future [

11].

Despite its crucial role, the implementation of SDG12 has proven to be highly complex, given the diverse political, economic, and social contexts of different countries [

12,

13]. A key challenge in realizing the goal is shifting away from the prevailing linear economic model that relies on extraction, consumption, and disposal toward a more circular, sustainable model that emphasizes efficiency, reuse, and recycling [

7,

14]. This transition is particularly challenging for countries that are heavily reliant on resource-intensive industries, such as fossil fuel extraction and agriculture [

15]. Furthermore, the economic disparities between developed and developing countries add a layer of complexity, as many nations lack the necessary financial resources, infrastructure, or technical expertise to implement these changes effectively [

4].

The global nature of SDG12 means that its success depends on the cooperation and contributions of countries across all regions [

9]. In particular, industrialized nations must lead by example in reducing consumption and adopting sustainable production methods, while also supporting developing countries in their transition toward more sustainable practices [

11]. International partnerships, capacity-building programs, and knowledge sharing are essential to address the disparities in resources, technology, and expertise, allowing all nations to benefit from sustainable development practices [

16,

17].

When considering the context of the Middle East, the implementation of SDG12 presents unique opportunities and challenges. Countries in the region, particularly those in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), have grown rapidly due to their abundant fossil fuel reserves, with economies largely shaped by the extraction and export of oil and natural gas. Qatar, for instance, is among the wealthiest nations globally, largely due to its natural gas and petroleum industries [

18]. However, this heavy dependence on non-renewable resources presents significant obstacles to the adoption of sustainable consumption and production practices. These challenges include high per capita consumption rates, waste generation [

19], and the environmental impacts of a resource-driven economy [

20]. Despite these hurdles, Qatar has taken significant steps toward integrating sustainability into its national development agenda, with efforts to diversify the economy, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and improve environmental stewardship [

21].

This paper aims to explore the challenges and complications, but also any success stories associated with the implementation of SDG12 in Qatar, maintaining and envisaging, at the same time, a local-to-global perspective. By examining the country’s strategies, policies, and outcomes, it will provide insights into how Qatar navigates the global imperative for sustainable consumption and production, particularly within the context of its oil-rich economy. The discussion will focus on the barriers faced by Qatar in implementing SDG12, the innovative approaches adopted to overcome these obstacles, and the successes that have marked its sustainability journey. Additionally, this paper will highlight the lessons that can be learned from Qatar’s experience, which may prove valuable for other countries with similar economic and environmental contexts.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, an analysis is attempted for all main targets and indicators, as those are specifically set and presented under the UN SDG12 [

8], and as per the obtained data for Qatar for the years 2016–2020 or, in some cases, 2016–2021. All available data are presented in this Section in the format of Tables, per target indicator.

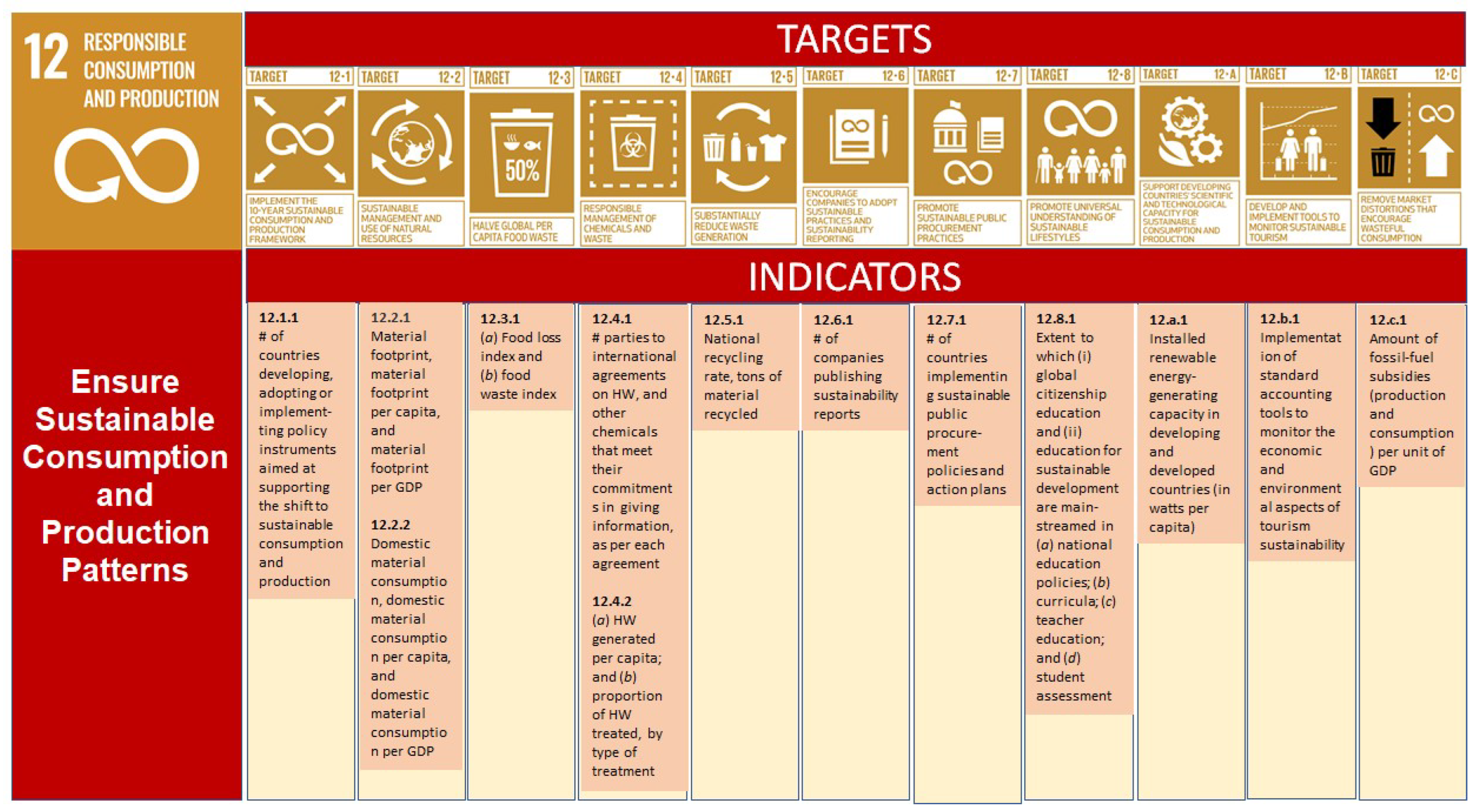

Figure 1 encapsulates all targets and indicators that fall under the SDG12 and the reader should use it as reference when proceeding with the below analysis of each individual target and indicator (or sub-indicator).

3.1. SDG Target 12.1

Based on

Table 1, Qatar has shown consistent progress and achievement in implementing Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) policies as part of the SDG Target 12.1.

The following major key findings can be derived:

SCP National Action Plans: Qatar has maintained a robust commitment to SCP implementation by consistently having SCP national action plans or mainstreaming SCP as a priority into national policies. From 2016 to 2022, the value remains at 1, indicating full alignment with SDG requirements.

Coordination Mechanism for SCP: Qatar has established and sustained a coordination mechanism for SCP throughout the reporting period (2016–2022). This mechanism ensures that relevant actors and stakeholders collaborate effectively to advance SCP priorities.

Implementation Activities for SCP: The data show that Qatar consistently engaged in “other implementation activities” related to SCP across the years. This reflects proactive steps beyond policy frameworks, suggesting tangible actions to promote sustainable production and consumption patterns.

SCP Policy Instruments: Qatar has maintained the presence of policy instruments for SCP for the entire period. This stability implies a strategic policy framework that underpins sustainable consumption and production goals.

Policies and Mechanisms (Sub-indicator e): While specific numerical data for the number of policies, instruments, and mechanisms in place are not provided, the consistent “1” values across other indicators suggest that necessary policies and systems are operational to support SCP.

3.1.1. Key Insights and Recommendations

The country has successfully embedded SCP into its national policies, demonstrating a long-term institutional commitment. The presence of coordination mechanisms and active implementation measures ensures that SCP efforts are not limited to strategy alone but extend to practical action. Stability over the 7-year period (2016–2022) underscores Qatar’s consistency in maintaining SCP as a national priority. The country is on track to meet its 2030 Goal, as indicated by achieving full compliance in all measured sub-indicators.

3.1.2. Final Remarks

The State’s performance in Target 12.1 reflects a well-structured and sustained approach to SCP implementation. The presence of action plans, coordination mechanisms, and policy instruments indicates that the country is effectively aligning with SDG12 objectives, positioning itself as a regional leader in sustainable consumption and production initiatives.

3.2. SDG Target 12.2

Table 2a,b highlights significant gaps in the reporting of indicators for Target 12.2, since both indicators under this target lack available data. With regards to Target 12-2-1, data are unavailable for material footprint, material footprint per capita, and material footprint per GDP. This hampers the assessment of resource use efficiency and the environmental impact of consumption in the State. Similarly, no data are reported for domestic material consumption, consumption per capita, or per unit of GDP (12-2-2).

Without this data, it is difficult to evaluate how resources are managed relative to population size or economic output. Nonetheless, the following observations and recommendations could, potentially, be made.

3.2.1. Key Observations

Data Gaps: The unavailability of data for both indicators indicates a challenge in monitoring and reporting resource management and efficiency in Qatar.

Impact on Policy Analysis: These gaps hinder Qatar’s ability to assess progress towards SDG Target 12.2 and identify areas requiring intervention to promote sustainable consumption and production.

Importance of Monitoring: Data for material footprint and domestic material consumption are critical for evaluating resource sustainability and ensuring efficient use of natural resources relative to economic and demographic growth.

3.2.2. Recommendations

Data Collection Frameworks: Establish or strengthen systems to collect and report data on material footprint and domestic material consumption.

Collaboration: Engage with international organizations or data providers to adopt standardized methodologies for measuring these indicators.

Regular Monitoring: Introduce periodic assessments to ensure data availability and track progress toward achieving Target 12.2 by 2030.

3.2.3. Final Remarks

The absence of data for Target 12.2 poses a significant challenge to evaluating Qatar’s resource efficiency and sustainability progress. Qatar should enhance data collection by developing an integrated national database that consolidates information from various ministries and sectors (e.g., energy, agriculture, waste management). Collaborating with international bodies like UNEP or UN DESA could help standardize data methodologies, particularly for underreported indicators like material footprint and domestic material consumption, necessary for this Target. Encouraging academic partnerships and using digital tools—such as remote sensing, AI-driven analytics, and blockchain for traceability—will further improve data quality, transparency, and frequency. Addressing these gaps through improved data systems will be essential for effective decision-making and achieving the SDG12 goals.

3.3. SDG Target 12.3

3.3.1. Reducing Food Loss and Waste

Table 3a shows the country’s efforts to minimize crop losses across major produce types. While the monetary value of crop losses for tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, and cantaloupes has generally declined from 2016 to 2021, the tonnage figures for certain crops, like tomatoes and cucumbers, reveal a contrasting trend of increased losses in quantity. For instance, tomato losses in tons increased steadily from 1409 tons in 2016 to 1808 tons in 2021, despite a decline in monetary value. This suggests improved pricing mechanisms or higher market values for the crops. Conversely, squash and cantaloupe losses decreased both in tonnage and monetary value, indicating improved post-harvest handling or supply chain efficiencies.

The aforementioned trends highlight progress, but also shows the challenge of addressing losses at the production stage. Enhanced storage, transportation, and market infrastructure could be pivotal in further reducing such losses [

5].

3.3.2. Food Redistribution and Beneficiary Support

The data from

Table 3b,c underline the State’s commitment to redistributing surplus food through initiatives like the Hifz Al Naema Center. The number of beneficiaries peaked in 2016 (486,202) and fluctuated in subsequent years, reaching a low in 2020 (204,153) before rebounding partially in 2022 (358,870). The COVID-19 pandemic likely contributed to the 2020 dip due to logistical challenges and restrictions on food redistribution efforts.

On the supply side, the donated quantities of food and beverages saw notable shifts. While the quantity of donated food decreased significantly during 2020 (102,077 kg), it rebounded in 2022 (568,153 kg) to surpass pre-pandemic levels. Beverage donations, on the other hand, peaked dramatically in 2019 (658,581 L) before stabilizing. These figures emphasize the resilience of Qatar’s food redistribution systems, even in the face of global disruptions. However, aligning the donations more consistently with beneficiary needs could amplify the impact.

3.3.3. Ensuring Food Safety and Compliance

Table 3d highlights the quantities of imported food destroyed due to non-compliance with safety and quality standards. Total destruction surged in certain years, such as 2019 (3.06 million kg) and 2021 (2.88 million kg), driven primarily by fruits, vegetables, and meat. For example, fruit and vegetable destruction spiked to over 2.19 million kg in 2019 and remained significant in 2021 (1.52 million kg). This pattern suggests increased vigilance in food inspections and enforcement of standards.

Interestingly, certain categories, like fats, oils, and dairy, show marked reductions in destruction quantities over time, indicating improved import management or quality control at the source. However, the recurring high destruction levels for perishable items point to the need for enhanced coordination between importers and regulators to minimize waste while maintaining food safety.

3.3.4. Key Takeaways, Recommendations, and Final Remarks

The State has made strides in reducing food loss, redistributing surplus, and enforcing food safety standards. The increasing reliance on redistribution networks like Hifz Al Naema underscores their importance in combating food waste while supporting vulnerable populations. However, further efforts are needed to address systemic inefficiencies in production and import supply chains.

Invest in Post-Harvest Technologies: Reducing crop losses, particularly for tomatoes and cucumbers, requires advanced storage, transport, and cold chain solutions to preserve quality from farm to market.

Optimize Redistribution Networks: Strengthening logistics and partnerships for initiatives like Hifz Al Naema can ensure a more consistent supply of donated food and beverages, especially during crises.

Enhance Import Practices: Improved supplier vetting, procurement planning, and collaboration between regulators and importers can minimize the destruction of non-compliant food while maintaining safety standards.

Public Awareness Campaigns: Promoting consumer responsibility through campaigns on food conservation and waste reduction can complement government efforts in achieving SDG12 targets.

In conclusion, while Qatar has laid a strong foundation for achieving SDG12, a focus on systemic improvements and stakeholder collaboration will be vital to sustaining progress and scaling impact. The State can invest in cold-chain logistics, ensuring that perishable goods maintain quality throughout the supply chain. Expanding smart inventory systems in retail and hospitality sectors can help forecast demand accurately and minimize surplus. Legal and financial incentives could encourage businesses to donate excess food, while stronger food safety standards and clearer expiration labelling would reduce household-level waste. Scaling up initiatives like the Hifz Al Naema Center and integrating food donation apps can streamline redistribution to those in need. Finally, consumer education on portion sizes, storage, and leftovers can further reduce waste at the source.

3.4. SDG Target 12.4

The country’s commitment to achieving the targets under SDG12, particularly sub-category 12.4, reflects a proactive approach to managing hazardous waste and chemicals in an environmentally sound manner [

32]. The provided data across three key tables highlight Qatar’s participation in international environmental agreements, its hazardous waste management practices, and efforts in monitoring and reducing hazardous waste production [

33,

34]. Below is a detailed discussion based on the findings reported in

Table 4a,b and more specifically

Table 4c.

3.4.1. International Commitments to Environmental Agreements

The country’s consistent engagement with international multilateral environmental agreements is a cornerstone of its strategy to manage hazardous waste and chemicals effectively. As indicated in

Table 4a, Qatar has met its commitments under five major international conventions: the Basel Convention, Minamata Convention, Montreal Protocol, Rotterdam Convention, and Stockholm Convention. These agreements are critical for controlling the transboundary movement of hazardous waste, addressing mercury pollution, protecting the ozone layer, and managing persistent organic pollutants. The State has adhered to these agreements, as shown by a continuous record of meeting obligations from 2016 to 2022, a fact that underscores its dedication to global environmental standards.

Qatar’s timely ratifications and accessions to these conventions further demonstrate its commitment. For example, the country ratified the Basel Convention in 1996, acceded to the Minamata Convention in 2020, and entered into force in 2021 (see

Table 4b). These efforts align with SDG12.4’s target of reducing the adverse impacts of hazardous waste on human health and the environment through international cooperation.

3.4.2. Hazardous Waste Generation and Treatment

The data on hazardous waste generation in

Table 4c provide a detailed picture of the trends in the State’s waste management. The quantity of hazardous waste generated per capita increased from 15.36 kg per capita in 2016 to 36.43 kg per capita in 2021. This significant rise reflects the country’s growing industrial activities and population. The corresponding increase in the total quantity of hazardous waste generated from 40,203 tons in 2016 to 100,005 tons in 2021 further emphasizes this trend.

In terms of waste treatment, the data reveal a clear focus on recycling and landfilling, with recycling accounting for approximately 45.9% of treated waste in 2021, down slightly from a peak of 49.1% in 2020. The incineration of hazardous waste, although increasing over the years, still constitutes a small percentage (5.9% in 2021), while landfill disposal remained a major treatment method, representing 47.6% of the total treated hazardous waste in 2021.

Notably, the quantity of hazardous waste exported surged significantly in 2021, reaching 12,664 tons, compared to a minimal amount in previous years. This increase could suggest enhanced efforts to dispose of hazardous waste through international channels, possibly due to capacity constraints in local treatment infrastructure or the country’s strategic shift toward international cooperation in waste management.

3.4.3. Proportional Treatment of Hazardous Waste

The relative distribution of hazardous waste treatment methods in

Table 4c indicates Qatar’s progress in diversifying its waste management strategies. While recycling has become a more prominent treatment method, landfills still play a major role, accounting for nearly half of all hazardous waste treatment in 2021. This reflects the country’s need for more sustainable recycling infrastructure and technologies to handle increasing hazardous waste volumes. Despite this, the consistent proportions of recycling and incineration suggest ongoing improvements in waste processing and a gradual reduction in reliance on landfills.

3.4.4. Key Takeaways, Recommendations, and Final Remarks

Qatar’s implementation of SDG12 sub-category 12.4 shows a positive trajectory in the management of hazardous waste and chemicals. However, there are several areas where further improvement is necessary:

Expansion of Recycling Infrastructure: While recycling rates have improved, there is a need to enhance recycling technologies to handle larger volumes of hazardous waste sustainably. This could help reduce the reliance on landfills and incineration.

Improved Waste Diversion Practices: The increase in hazardous waste exports in 2021 suggests a growing capacity to manage waste outside the country. However, Qatar could aim for a more robust internal treatment system to reduce dependency on external disposal methods.

Monitoring and Enforcement: Strengthening the monitoring and enforcement of waste management regulations is essential to ensure that hazardous waste is treated according to international standards, reducing its environmental impact.

In conclusion, Qatar has made significant strides in managing hazardous waste, demonstrating strong international cooperation and adherence to global agreements. By focusing on sustainable waste treatment technologies and expanding recycling capacities, Qatar can further reduce the environmental impact of hazardous waste and contribute to global environmental goals under SDG12.

3.5. SDG Target 12.5

The State’s efforts to reduce waste generation and improve recycling practices, in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12, are evident in the trends shown in

Table 5. This Table provides data on the solid waste recycled by type from 2016 to 2021, showcasing both the challenges and progress the State has made in enhancing its recycling infrastructure. Although the country has witnessed fluctuations in recycling volumes over the years, certain materials, like plastic and glass, have seen significant improvements in recycling rates.

3.5.1. Total Recycling Trends

The total quantity of recycled solid waste in Qatar decreased from 53,384 tons in 2016 to 12,725 tons in 2020, before seeing an uptake to 21,698 tons in 2021. This fluctuation reflects broader challenges in recycling infrastructure, waste generation patterns, and possibly the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on waste collection and processing in 2020. Despite the dip in 2020, the increase in 2021 signals a potential recovery or improvement in the recycling systems, possibly linked to new policies or public awareness campaigns. Nevertheless, the country’s recycling volume still remains low relative to its waste generation, suggesting room for further expansion of recycling efforts.

3.5.2. Plastic Waste Recycling

Plastic waste recycling in Qatar presents a mixed picture. In 2016, 784 tons of plastic were recycled in the State, a figure that decreased dramatically in the following years, reaching as low as 76 tons in 2019. However, the quantity of recycled plastic surged in 2021, reaching a total of 1222 tons, the highest level recorded over this six-year period. This increase could be attributed to stronger regulations or public initiatives aimed at reducing plastic waste and boosting recycling efforts [

35]. The success of this initiative is an encouraging sign that Qatar is addressing the challenge of plastic waste, which is a global environmental issue [

36,

37].

3.5.3. Recycling of Paper, Scrap Metal, and Glass

Recycling trends for paper (carton), scrap metal, and glass show more mixed results. Paper recycling, for example, saw a decline from 1034 tons in 2016 to just 111 tons in 2020. However, it picked up slightly in 2021, reaching 246 tons. The decrease in paper recycling could indicate challenges in waste sorting and collection systems or changes in consumer behavior. Similarly, scrap metal recycling dropped sharply from 1134 tons in 2016 to just 189 tons in 2017 but rebounded in 2021 to 508 tons. These fluctuations may be linked to varying demand for materials or the efficiency of metal recycling operations.

Glass recycling, on the other hand, saw a consistent increase over the years, rising from 3634 tons in 2016 to 8677 tons in 2021. This indicates a strong recycling infrastructure for glass and perhaps growing public and private sector efforts to recycle this material, which is relatively easy to recycle and has a high market demand.

3.5.4. Wood Recycling

Wood recycling in Qatar, however, exhibited a substantial decline from 46,798 tons in 2016 to just 5853 tons in 2020, before recovering to 11,045 tons in 2021. Wood waste, especially from construction and demolition activities, is often more challenging to recycle, which could explain the significant fluctuations in its recycling rate [

38]. Qatar’s heavy construction industry may contribute significantly to wood waste, and the low recycling figures for wood suggest a need for more specialized waste management and recycling facilities.

3.5.5. Recommendations and Final Remarks

Qatar’s efforts to reduce waste generation through recycling show both progress and setbacks, highlighting the complexity of waste management in rapidly developing urban environments. While the recycling of glass and plastic has shown promise, and wood recycling is on the rebound, overall recycling rates remain relatively low compared to global standards. To meet the SDG12 target of substantially reducing waste generation by 2030, Qatar should focus on:

Strengthening Recycling Infrastructure: Expanding and improving the infrastructure for recycling, particularly for challenging materials like paper, wood, and scrap metal, will be essential to increase the national recycling rate.

Public Awareness and Behavior Change: Increased public awareness campaigns focusing on reducing waste generation, separating recyclables, and improving consumer participation in recycling programs can help raise recycling rates.

Innovation in Waste Management: Encouraging innovation in recycling technologies and practices, such as increasing the capacity to process complex materials like plastic, can help the country move closer to its waste reduction goals.

In conclusion, Qatar has made strides in certain areas of waste recycling, but significant work remains to ensure that recycling rates substantially increase across all material types by 2030.

3.6. SDG Target 12.6

The State has made considerable progress in encouraging companies to adopt sustainable practices, particularly through sustainability and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting. As seen in

Table 6a,b, the country has seen an increasing number of companies—both large-scale and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—engage in sustainability and social responsibility reporting, marking an important step towards meeting the objectives of SDG12. However, there remains significant potential for further growth, particularly in the expansion of ESG reporting and the adoption of sustainability practices across all sectors.

3.6.1. Sustainability and Social Responsibility Reporting in 2019

According to

Table 6a, a total of 170 companies in the State published sustainability or social responsibility reports in 2019, including 32 large-scale companies and 138 SMEs. The goal for 2030 is to increase these numbers, suggesting that while current efforts are notable, there is a need for a broader adoption of sustainability reporting in both large and small businesses. The 170 companies represent a start, but achieving SDG12 requires more companies, especially large-scale ones, to integrate sustainability into their operations and report on it transparently [

39].

The number of SMEs publishing such reports is particularly encouraging, as these businesses often have fewer resources to invest in sustainability initiatives. However, the overall focus for 2030 should be on increasing the number of large-scale companies engaging in sustainability reporting, given their greater potential to impact the economy and environment.

3.6.2. Growth in ESG Reporting

The data from

Table 6b on ESG reports show a noticeable trend towards increasing awareness of corporate responsibility among major Qatari companies. The Table reveals that, starting from 2017, a number of key corporations, including Doha Bank, Qatar National Bank, and Ooredoo, began publishing ESG reports. For example, in 2021, companies such as Doha Bank, Aamal Company, and Qatar National Bank achieved a 100% ESG reporting rate, showcasing their commitment to transparency in environmental, social, and governance factors.

However, not all companies have maintained consistent levels of ESG reporting. Some companies showed fluctuations in their reporting percentages, with certain years exhibiting a lower commitment (e.g., Qatar National Bank’s drop to 3% in 2020). The inconsistency in reporting highlights the need for stronger corporate governance mechanisms to ensure that companies remain committed to sustainable reporting practices over time.

The ESG reporting initiative, launched in 2017, has grown in prominence, with a growing number of Qatari companies adopting these practices. In 2021, Ooredoo joined the ranks of consistent ESG reporters, further demonstrating the trend toward greater corporate responsibility. However, the gap in reporting between different companies suggests that there are still hurdles to overcome in ensuring widespread, consistent ESG reporting across the private sector.

3.6.3. Opportunities and Challenges for 2030

Looking ahead to 2030, the State has set a clear goal of increasing the number of companies adopting sustainable practices and publishing sustainability and ESG reports [

21]. However, achieving this goal requires overcoming several challenges. For one, expanding ESG reporting requires addressing the barriers that smaller companies and those outside of major industries face. Incentives, education, and capacity-building initiatives could help SMEs understand the long-term benefits of sustainability reporting and build the necessary frameworks for reporting.

Moreover, Qatar must work toward ensuring that ESG reports provide meaningful insights and are aligned with international standards. While the increase in reporting is positive, the quality of these reports should be a priority in order to drive real change. Companies should be encouraged to adopt internationally recognized frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) to ensure their reports are impactful and comparable.

3.6.4. Insights and Recommendations

The State’s progress in encouraging companies to adopt sustainable practices and report on their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance is commendable but requires further efforts. The number of companies engaging in sustainability and ESG reporting has increased, particularly among larger corporations. However, to fully meet the targets of SDG12 by 2030, Qatar must expand this effort to include more companies, enhance the consistency of ESG reporting, and improve the quality of these reports. By strengthening governance frameworks, offering incentives, and fostering a culture of transparency, Qatar can continue to lead by example in corporate sustainability in the region.

3.7. SDG Target 12.7

Based on the data presented in

Table 7, Qatar has consistently demonstrated a strong commitment to implementing Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP) policies and action plans, in line with the SDG12, which emphasizes sustainable consumption and production patterns. The Table reveals that Qatar has maintained a solid performance in this area from 2016 to 2022, with an overall score of 78% in its public procurement practices, reflecting a steady commitment to sustainable procurement.

The Table shows that Qatar has established key components of sustainable public procurement policies, action plans, and regulatory frameworks. Specifically, the data indicate that Qatar has fully implemented regulatory requirements for public procurement, with a perfect score of 1 in each year from 2016 to 2022 for the existence of policies, action plans, and regulatory requirements. This indicates that the country has formalized its commitment to sustainable public procurement within its policy frameworks and national priorities.

Furthermore, the regulatory framework supporting these policies has also received a perfect score of 20 out of 20, indicating that Qatar has put in place comprehensive systems to guide and govern its public procurement. The presence of such a framework is crucial for ensuring that public procurement practices align with sustainable development goals, as it offers clear guidelines for procurement practitioners.

In terms of practical support for procurement practitioners, the State has again achieved the highest score of 20 out of 20 from 2016 to 2022. This suggests that the country has made significant efforts to equip its procurement officials with the necessary tools, training, and resources to effectively implement sustainable procurement practices. This aspect is essential for the success of sustainable procurement policies, as it ensures that those responsible for procurement decisions are adequately prepared to integrate sustainability considerations into their daily operations.

However, the Table also highlights that while Qatar’s procurement criteria have consistently scored 18 out of 20, there is still room for improvement. The procurement criteria, which guide the selection of sustainable products and services, are crucial for ensuring that public procurement practices are truly sustainable. The score of 18 suggests that while these criteria are robust, there may be some gaps or areas that could be further refined to fully align with global sustainability standards.

Additionally, Qatar’s public procurement control system has achieved full marks (20 out of 20), signifying that the country has a stringent oversight mechanism in place to monitor and enforce compliance with its sustainable procurement policies. This control system ensures that the policies are not only established but also effectively enforced, which is critical to maintaining accountability and transparency in the public procurement process.

Looking toward the future, the goal by 2030 is for the country to achieve a perfect score of 100%. The country’s consistent performance over the years indicates that it is on track to meet this target, with all areas of public procurement receiving full scores, particularly the percentage of public procurement, which will likely reflect the increased proportion of sustainable products and services in government procurement.

In conclusion, the country has made significant strides in implementing sustainable public procurement policies and action plans, as evidenced by the data provided. The country’s strong regulatory framework, comprehensive support for procurement practitioners, and effective control systems set a solid foundation for achieving even higher levels of sustainability in public procurement by 2030. However, further refining the procurement criteria could help Qatar fully align its procurement practices with global sustainability standards, ensuring that the country’s public procurement system plays a key role in promoting sustainable development.

3.8. SDG Target 12.8

The State of Qatar has shown consistent progress in mainstreaming global citizenship education (GCE) and education for sustainable development (ESD) within its education system from 2016 to 2022. The data reveal that the country has effectively integrated these principles into key areas of its national education framework, aligning with the target set under SDG12, Target 12.8.

Table 8 indicates that global citizenship education and education for sustainable development are fully mainstreamed in national curricula, with a score of 1 for each year from 2016 to 2022. This suggests that sustainability and global citizenship themes are embedded in the educational content delivered to students at all levels. This mainstreaming of sustainability principles into the curriculum reflects Qatar’s commitment to fostering an environmentally conscious and globally aware generation, equipped with the knowledge and skills needed to support sustainable development.

Similarly, the data show that these education elements are also integrated into national education policies. The score of 1 across all years suggests that the government has implemented clear policies that prioritize the inclusion of global citizenship and sustainable development in educational planning and governance. This institutional commitment is crucial for ensuring that sustainable practices are not just taught but also upheld as part of national priorities in the education sector.

In terms of student assessment, the country has retained the mainstreaming of global citizenship education and education for sustainable development in assessment frameworks, with consistent scores of 1 from 2016 to 2022. This implies that students are evaluated on their understanding and application of sustainability principles, ensuring that sustainability is not just an abstract concept but one that is actively assessed in student performance.

Teacher education is another area where Qatar has shown consistent alignment with sustainability goals. The data reveal that global citizenship education and education for sustainable development have been integrated into teacher training programs, as indicated by a score of 1 each year. This is a vital step, as educators play a crucial role in imparting sustainability knowledge and shaping attitudes toward global citizenship. By preparing teachers to deliver these topics effectively, the State ensures that its educational system is well-equipped to promote sustainability.

Overall, the data show that the country has made significant strides in embedding sustainability and global citizenship education throughout its education system. Its educational policies, curricula, assessment methods, and teacher training programs all reflect a comprehensive approach to achieving Target 12.8 of SDG12. These efforts demonstrate Qatar’s commitment to equipping its citizens with the knowledge, values, and skills needed to live sustainably and in harmony with nature. As the country progresses toward 2030, these foundational educational reforms will play a crucial role in shaping a society that embraces sustainability at every level.

3.9. SDG Targets 12.a, 12.b, and 12.c

As evidenced from above, Qatar is actively engaging with several aspects of SDG12, focusing on achieving responsible consumption and production patterns, both within the country and in support of developing nations. With reference to SDG12.b and SDG12.c (monitoring sustainable tourism and rationalizing fossil fuel subsidies), these are addressed through a combination of government policies, monitoring systems, and international cooperation, as shown in

Table 9a,b.

3.9.1. SDG12.a: Supporting Developing Countries’ Scientific Capacity for Sustainable Consumption

In the context of SDG12.a, the country has made progress in terms of renewable energy, with data reflecting a steady increase in renewable energy capacity. The installed renewable energy-generating capacity per capita has grown from 18.3 watts in 2016 to 17.3 watts in 2020. Although the per capita capacity has fluctuated slightly over the years, this increase indicates Qatar’s commitment to renewable energy, crucial for shifting toward more sustainable consumption and production patterns. This reflects the country’s role in supporting scientific and technological advancements in energy, aligning with its broader environmental goals. However, given the country’s small population, the focus on renewable energy will need to be expanded as it continues to grow its role in regional and international sustainability initiatives.

3.9.2. SDG12.b: Implementing Tools to Monitor Sustainable Tourism

For SDG12.b, the State has implemented standard accounting tools to track the economic and environmental impacts of tourism. The country has consistently utilized seven Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) tables to monitor domestic and inbound tourism expenditures, tourism employment, and the production accounts of tourism industries. This indicates Qatar’s ability to evaluate the sustainability of its tourism sector and ensure that its growth is aligned with national and international sustainability objectives. However, it is important to note that tools such as energy flow accounts, water flow accounts, and greenhouse gas emissions accounts (which are crucial for assessing the environmental footprint of tourism) have not yet been implemented. The absence of these tools suggests a need for further integration of environmental considerations into tourism management. Furthermore, we now propose specific interventions, including:

Establishing integrated environmental-economic accounting systems, such as the SEEA (System of Environmental Economic Accounting), to support SDG12.b monitoring.

Mandating cross-ministerial collaboration between tourism, energy, and environmental agencies to consolidate relevant datasets.

3.9.3. SDG12.c: Rationalizing Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Regarding SDG12.c, the State faces challenges in phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that contribute to wasteful consumption. The lack of available data on fossil fuel subsidies per unit of GDP for Qatar suggests that efforts in this area may not be as transparent or monitored as other sustainability initiatives. The country’s reliance on fossil fuel resources means that transitioning away from subsidies will need careful consideration to protect vulnerable communities and the economy. While Qatar has made significant strides in renewable energy, it will need to rationalize its fossil fuel subsidies to reduce their environmental impact, aligning with the global shift towards sustainability.

3.9.4. Insights and Final Remarks

Qatar has shown significant progress in several SDG12-related areas, particularly in promoting renewable energy and tourism sustainability. However, challenges remain in terms of comprehensive monitoring of environmental impacts in tourism and fossil fuel subsidies. Moving forward, the country will need to further integrate sustainability into its public procurement practices, enhance its monitoring of fossil fuel subsidies, and implement more comprehensive tools to assess the environmental impacts of its tourism sector. These steps are critical for ensuring that the country meets its 2030 goals and continues to contribute to global sustainability efforts.

Finally, we propose adopting transparent, open-access reporting platforms where national indicators aligned with SDG12 targets are regularly updated and capacity-building partnerships with international organizations (e.g., UNEP, UNWTO) to enhance technical expertise in environmental data monitoring.

4. Conclusions

Qatar’s efforts toward achieving SDG12—responsible consumption and production—demonstrate notable progress, persistent challenges, and clear opportunities across its various targets. The country’s commitment to sustainability is reflected in its strong policy frameworks, innovative initiatives, and proactive measures, yet significant structural barriers and gaps in implementation remain, requiring targeted actions to meet the 2030 Agenda.

Fossil fuel subsidy reform could begin with enhanced data transparency and be followed by gradual reallocation measures that safeguard low-income populations through targeted energy support. In the area of waste management, policies such as extended producer responsibility (EPR), mandatory industrial waste audits, and financial incentives for recycling could drive improvement. Regarding ESG reporting, a practical strategy could involve mandating ESG disclosures for all publicly listed companies, aligned with global standards and enforced through independent oversight bodies. Including such detailed pathways in future research will strengthen this study’s policy relevance and practical utility.

Prior to analysing the successes and obstacles obtained under each target and sub-indicator, we should elaborate a bit more on the importance of public awareness that has been mentioned many times in the current work. Public awareness can be boosted through a multi-tiered strategy. Integrating sustainability education into school curricula from an early age can nurture long-term behavioural change. Government-led campaigns using social media, local influencers, and community events can effectively spread messages about reducing food waste, energy conservation, and responsible purchasing. Public institutions and businesses can serve as role models by adopting green practices and showcasing their impact. Finally, collaborating with religious leaders and cultural organizations could also help align sustainability messages with local values, improving public engagement across diverse segments of society.

The State has excelled in embedding SCP principles into its national development agenda under Target 12.1. The presence of robust action plans, effective coordination mechanisms, and SCP-related policies ensures the country’s long-term institutional commitment to sustainability. From 2016 to 2022, Qatar consistently maintained a full alignment with SDG12 requirements, demonstrating stability and tangible efforts beyond mere strategy.

Under Target 12.3, Qatar has made considerable progress in addressing food loss and waste. Initiatives like Hifz Al Naema have successfully redistributed surplus food to underprivileged communities, even rebounding impressively after disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, crop losses remain a concern, with increases in tonnage for major crops like tomatoes and cucumbers despite a decline in their monetary value. Enhanced infrastructure for storage, transportation, and supply chain management will be critical to further reducing food loss. The State’s ability to maintain a functional and resilient food redistribution system highlights its success in mitigating food waste and ensuring social equity.

Progress under Target 12.4, which focuses on the environmentally sound management of chemicals and waste, is marked by strict regulatory controls on hazardous material imports and disposal. While this demonstrates Qatar’s proactive approach, scaling up infrastructure to handle chemical waste, particularly in industrial sectors, remains a challenge. Robust monitoring systems and greater investment in treatment facilities are required to strengthen compliance and environmental protection.

The country’s progress in waste reduction and recycling under Target 12.5 remains modest, reflecting the need for a more comprehensive waste management infrastructure and greater public participation. Efforts to implement circular economy principles are still in their early stages, and recycling systems lack the scale necessary to significantly impact waste generation. Targeted investments in waste segregation systems, public awareness campaigns, and recycling facilities will be essential to address these gaps and promote sustainable waste management.

Under Target 12.6, Qatar has encouraged corporate sustainability practices, with growing interest from businesses in integrating sustainability principles. However, reporting remains limited among private sector entities. Creating incentives, strengthening regulatory frameworks, and providing capacity-building programs will help drive greater corporate transparency and engagement with SDG12 objectives.

SPP, under Target 12.7, stands as a significant success story. The State’s government has effectively incorporated environmental and social criteria into its procurement processes, demonstrating an innovative approach to driving sustainability through public spending. Scaling SPP principles to the private sector could unlock further systemic change and position Qatar as a regional leader in sustainable procurement practices.

Qatar has also achieved notable progress in renewable energy adoption under Target 12.a. Increasing per capita renewable energy capacity, particularly through solar projects, highlights the country’s efforts to diversify its energy mix. While progress is commendable, it must accelerate further to reduce Qatar’s reliance on fossil fuels and achieve a cleaner, more sustainable energy future.

For Target 12.8, which focuses on promoting awareness and understanding of sustainable lifestyles, Qatar has initiated education programs and awareness campaigns to engage the public, particularly youth. Collaborations with organizations like Qatar Foundation have promoted sustainability concepts in schools and communities. However, the challenge lies in translating this awareness into widespread, long-term behavioral change. Qatar must broaden the scope of its campaigns to include waste reduction, circular economy principles, and responsible consumption, ensuring deeper societal engagement.

Gaps remain evident under Target 12.2, where the lack of data on material footprint and domestic material consumption presents a significant barrier to assessing resource efficiency. Without this data, it is difficult to evaluate Qatar’s progress and identify areas requiring intervention. Establishing robust data collection frameworks, adopting standardized methodologies, and conducting periodic assessments will be essential to close this gap and enable evidence-based policymaking.

A major structural challenge persists under Target 12.c, as fossil fuel subsidies continue to incentivize resource-intensive consumption patterns. While the country has shown a commitment to sustainable policies, rationalizing subsidies remains critical to promoting responsible energy use and aligning economic incentives with sustainability objectives.

To sum up, Qatar’s progress on SDG12 reflects a combination of significant achievements, persistent gaps, and untapped opportunities. Success stories such as food redistribution initiatives (12.3), sustainable public procurement (12.7), and renewable energy adoption (12.a) highlight the country’s ability to implement impactful programs and policies. However, addressing data gaps (12.2), scaling recycling infrastructure (12.5), fostering corporate sustainability reporting (12.6), and promoting behavioral shifts through enhanced awareness campaigns (12.8) are critical for achieving SDG12 in its entirety.

Moreover, to deepen the analytical lens of this study, it should be reported that several theoretical frameworks relevant to sustainable production and consumption were or could be considered. Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) offers a method for assessing environmental impacts across the entire life span of products, providing insights into how Qatar can reduce waste and emissions at each stage. The Circular Economy model is particularly applicable, emphasizing the reuse, recycling, and efficient management of resources. Sociotechnical Transitions Theory helps interpret systemic shifts towards renewable energy and sustainable practices by focusing on the co-evolution of technology, institutions, and society. Ecological Modernization Theory (EMT) aligns with Qatar’s strategies that integrate technological innovation and policy reform to address environmental challenges. Social Practice Theory (SPT) complements this by emphasizing how everyday consumption habits and routines can be reshaped to support national sustainability goals. Finally, the Doughnut Economics model serves as a comprehensive framework, advocating for policies that ensure environmental sustainability while meeting social needs. The incorporation and/or consideration of these frameworks not only enhances the theoretical grounding of the analysis but also situates Qatar’s efforts within broader global discourses on sustainable development.

By leveraging its existing successes, the State has the potential to emerge as a regional leader in sustainable consumption and production. Addressing fossil fuel subsidies, improving waste management systems, and prioritizing circular economy principles will further strengthen the country’s sustainability agenda. With sustained efforts, enhanced monitoring, and strategic investments, Qatar can successfully navigate the challenges and opportunities of SDG12, setting an example for other nations with similar economic and environmental contexts.