1. Introduction

In today’s higher education systems, the influence of technology and its associated innovations is evident across nearly every aspect of teaching and learning. This reflects a growing recognition of the importance of integrating digital tools into academic environments to promote inclusive and sustainable education. With the continuous advancement of technological solutions, there has been significant growth in the availability, accessibility, and use of electronic resources, internet-based platforms, and academic databases. These tools are actively applied to support, enhance, and streamline the teaching and learning process through educational and advisory programs offered by universities, contributing directly to the goals of equity, access, and innovation in higher education.

Among the most significant and rapidly evolving of these innovations is artificial intelligence (AI), which utilizes deep learning models to generate content that closely resembles human responses to complex stimuli. This capability has enabled AI to become increasingly embedded in diverse domains of life [

1], including both school and higher education settings [

2]. As AI technologies continue to progress, they are expected to drive further transformation within higher education systems, offering new opportunities to personalize learning and reduce disparities in access to knowledge. At the same time, they present unavoidable challenges, such as the reconfiguration of industries involving communication technologies, software development, data management, business operations, interactive systems, cybersecurity, and social media platforms [

3,

4,

5].

In response to these developments, universities are increasingly adopting AI across various operational areas—administrative, instructional, and educational—to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of student learning [

6,

7,

8]. AI supports the personalization of learning experiences, enhances student engagement, and strengthens learning-related decision-making. Moreover, it enables the automation of routine tasks, optimizes institutional resources, and advances scientific research by analyzing large datasets to guide researchers toward original and impactful topics. Critically, AI also enables more inclusive educational practices by adapting instructional content to diverse learning abilities and cultural contexts [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Through such applications, AI plays a pivotal role in advancing the objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly SDG 4, which calls for inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all.

Effectively integrating AI into higher education requires a reconsideration of the role university administrations play in enabling equitable access to and responsible engagement with AI. While technological dynamic capabilities are essential, they may not be sufficient in the digital age, particularly when it comes to anticipating and supporting students’ awareness, understanding, and competent use of AI tools. In the 21st century, information is pervasive and addressing “data illiteracy” alone no longer equips students with the skills necessary to read, analyze, and manage complex information environments. There is now an increasing need to enhance “AI literacy,” which enables students to engage critically and intelligently with AI systems to identify, evaluate, and apply information [

13,

14,

15]. As such, university administrations must not only possess technological agility but must also actively deploy it to foster student development, reduce disparities in digital access, and build a foundation for sustainable, inclusive learning.

Several studies have highlighted the importance of this shift. For example, Al-Masry and Tarawneh recommend that university administrations embrace AI applications to advance institutional transformation across education, research, community engagement, and resource management [

16]. Similarly, Alatel et al. highlight the importance of raising awareness among faculty and students regarding AI’s significance in educational contexts, noting its potential to help institutions achieve their goals with greater efficiency and effectiveness [

17]. Al-Shammari further stresses the importance of establishing robust infrastructure, administrative frameworks, and ethical guidelines to enable the effective and regulated use of AI [

18]. Otoom likewise calls for stronger efforts to promote AI integration as part of institutional modernization [

19].

More recently, Delello et al. found that although educators are adapting to the use of AI tools like ChatGPT -4, they report a lack of institutional policies and call for AI-specific professional development and ethical training [

20]. In a parallel finding, Nelson et al. [

21] report that university students in Ecuador largely regard AI-generated work as academic dishonesty and advocate for educational policies that promote constructive and ethical uses of AI. Together, these studies suggest that the responsible integration of AI in higher education requires more than access to tools—it demands comprehensive strategies that include student awareness, clear policy frameworks, ethical guidance, and institutional support, especially in the context of sustainable and inclusive educational development.

To conceptualize how universities can meet these demands, this study draws on Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT), originally developed by Teece et al. [

22]. DCT refers to an organization’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources to adapt to change. It emphasizes strategic agility over routine operations and offers a useful lens for examining how institutions can mobilize technological and organizational capacities to support AI literacy and equitable access. For instance, universities may reconfigure IT infrastructure to ensure secure and equitable access to AI tools (reconfiguring), adapt faculty development programs to include generative AI use cases (learning), or integrate AI ethics modules into existing curricula (integrating). These examples reflect core dynamic capabilities that can influence how effectively institutions foster AI literacy.

Despite these global discussions, a considerable knowledge gap persists regarding how various stakeholders (students, faculty, and administrators) understand and engage with AI, particularly in relation to their respective roles in shaping future-ready learning environments [

23,

24,

25]. Unlike previous studies, which have tended to focus either on student attitudes or institutional readiness in isolation, this study aims to explore the direct relationship between university administration’s technological dynamic capabilities and students’ awareness of AI use. It also introduces a novel application of Dynamic Capabilities Theory within the context of higher education in the Arab region, where empirical evidence on AI-related institutional engagement remains limited. This gap is particularly significant as universities in the region are under growing pressure to modernize educational delivery and ensure students are prepared to navigate evolving digital landscapes. Understanding the link between institutional capabilities and student AI literacy can inform effective policy, curriculum development, and support services. By situating the research within a specific institutional context, the study addresses the need for evidence-based strategies to support responsible and effective AI integration in education.

While institutional interest in AI grows, significant disparities persist in students’ awareness and proficiency in AI use. This raises critical questions about the role of administrative capacities in equipping students to participate meaningfully in the AI-driven knowledge economy. Recent international studies show that students’ perceptions of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT are shaped by institutional and cultural contexts. In a large U.S.-based study, Baek et al. found that policies, demographics, and perceived risks influence student use of ChatGPT, especially for writing and coding [

26]. Their findings highlight how generative AI may reinforce existing inequalities in higher education. In Finland, a study by Rüdian et al. showed that students often rejected AI-generated feedback when aware of its machine origin, citing a lack of emotional and social value [

27]. In India, Mondal et al. found that medical students use AI tools to simplify content and streamline assignments but had concerns about hallucinations, privacy, and overreliance [

28].

Complementing these studies, emerging research on AI literacy explores the knowledge, skills, and ethical understanding students need to engage with AI effectively. For example, Wu et al. developed an evaluation framework grounded in the UNESCO and KSAVE models, revealing demographic differences in AI competencies among students [

29]. In a scoping review, Laupichler et al. identified recurring themes in pedagogical approaches and curricular gaps, underscoring the field’s early stage of development [

30]. Together, these studies highlight the need for institutionally supported strategies that promote responsible, equitable, and pedagogically sound use of generative AI.

Despite this growing body of international research, most studies continue to focus on individual user experiences or educational practices. Far fewer have examined the organizational capabilities that enable or constrain AI adoption within universities. In particular, the relationship between university-level technological readiness and students’ engagement with AI tools remains underexplored. This study builds on that gap by examining how institutional dynamic capabilities influence students’ awareness and use of AI. The focus on a public university in Oman offers timely insight into how higher education institutions in the Gulf region are responding to AI integration amid ongoing digitization and evolving pedagogical demands.

To explore these issues, the study focuses on the College of Education at Sultan Qaboos University and addresses the following research questions:

What is the level of the university administration’s technological dynamic capabilities and the level of students’ awareness of using AI tools at the College of Education, Sultan Qaboos University?

What is the nature of the correlation between the university administration’s technological dynamic capabilities and students’ awareness of AI usage?

Which specific dimensions of technological dynamic capabilities can predict students’ awareness in using AI tools at Sultan Qaboos University?

2. Theoretical Framework

Amid the ongoing transformations driven by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, AI has emerged as a powerful force reshaping global sectors, including higher education. Beyond enhancing productivity and institutional agility, AI offers transformative potential to foster equitable access to quality education and prepare students for a rapidly evolving knowledge economy. It has been shown to improve productivity, skills, and capabilities among learners and workers, contributing to international economic development [

31,

32]. In the educational sphere, AI is no longer a peripheral innovation but a strategic asset for universities seeking to respond to change, adapt to societal demands, and advance inclusive and sustainable development [

5,

19]. However, the educational value of AI depends not only on access but also on how well institutions implement it through thoughtful, adaptive strategies, making Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) a compelling framework for understanding institutional readiness.

Originally introduced by Teece et al., Dynamic Capabilities Theory posits that an institution’s competitive advantage lies in its ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies in response to change [

3,

20]. These capabilities are not routine operational functions but strategic processes that enable continuous innovation, learning, and adaptation [

33,

34]. In the context of higher education, DCT offers a valuable lens for examining how university administrations can mobilize and reconfigure their resources, especially technological ones, to responsibly and inclusively embed AI into teaching, learning, and institutional operations. The theory is typically structured around three components:

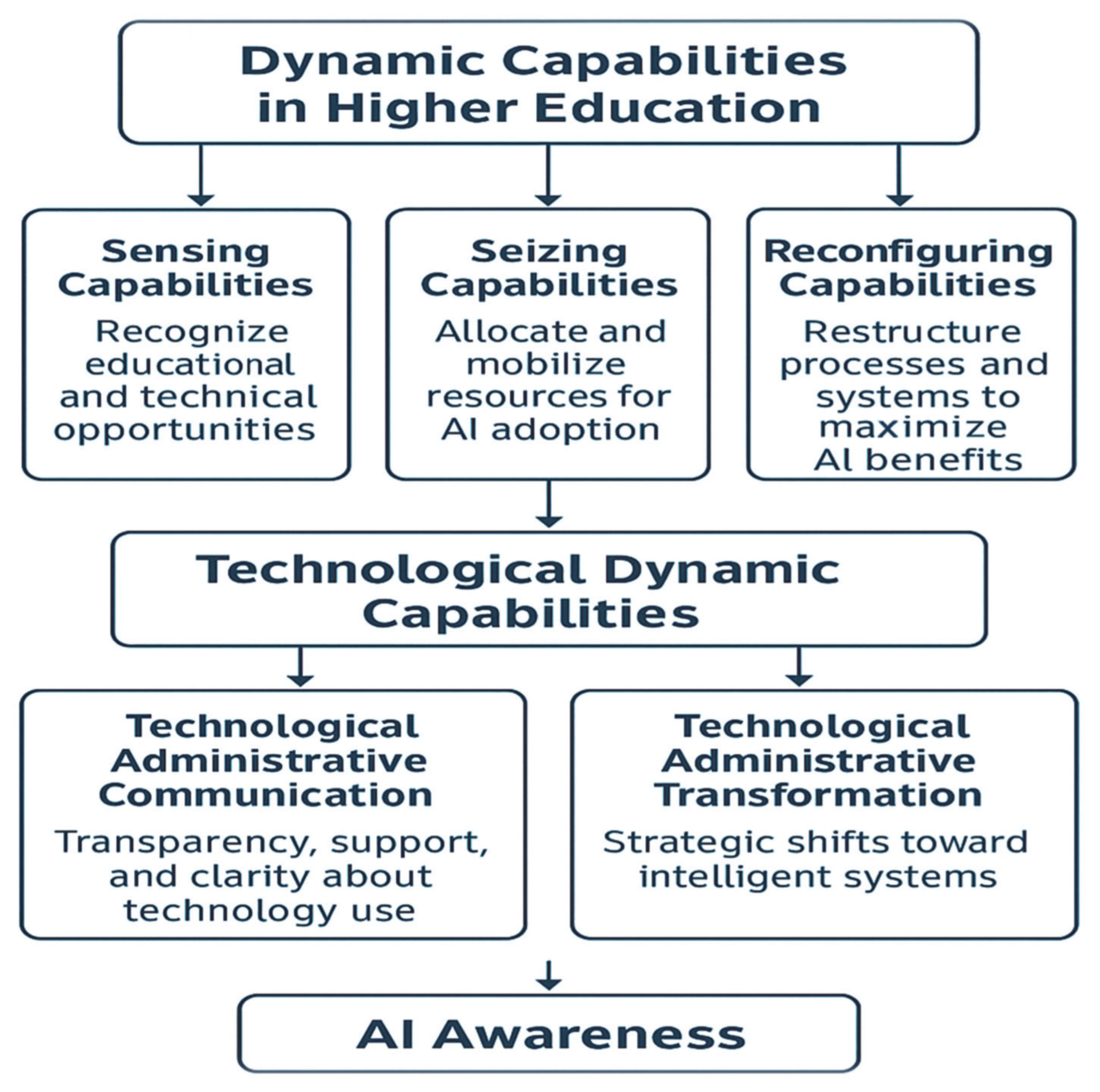

Sensing Capabilities: The ability to recognize emerging educational and technological opportunities, such as identifying AI tools that support personalized learning, inclusive teaching practices, and innovative research.

Seizing Capabilities: The capacity to allocate and mobilize institutional resources toward effective AI adoption, including integrating AI in curriculum design, learning analytics, student feedback systems, and adaptive assessments.

Reconfiguring Capabilities: The ability to restructure institutional processes and systems to maximize AI’s long-term educational benefits, such as using predictive analytics to support retention, revising teaching roles, and fostering sustainable academic innovation.

These dynamic capabilities enable institutions to move beyond operational capabilities that generate short-term value toward capabilities that bring about long-term strategic change in their resource base [

22,

35,

36]. An extension of DCT is the concept of technological dynamic capabilities, which specifically refers to an institution’s ability to adapt and align technological infrastructures, processes, and expertise with evolving educational needs [

37]. Technological capabilities are defined as “the organization’s technological resources, capacities, and potentials that it seeks to invest and exploit through its workforce’s expertise, skills, and capabilities to effectively and efficiently improve the quality of its products and operations” [

38]. These capabilities are further categorized into the following [

39]:

Technological Competence: Infrastructure, systems, and digital proficiency.

Organizational Competence: Institutional agility in adapting to technological change.

Innovative Competence: The ability to integrate novel technologies and services.

Marketing Competence: Responsiveness to evolving user needs and expectations.

Knowledge Management Competence: Practices that foster value through information sharing and knowledge creation.

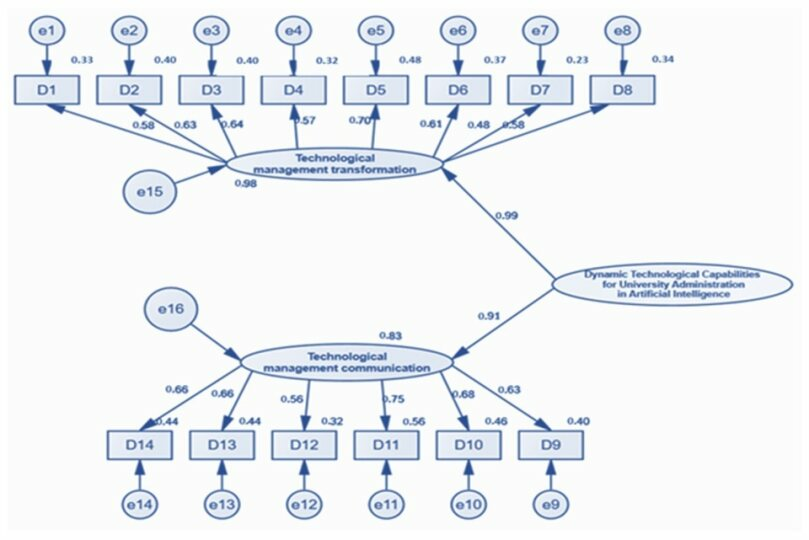

In the context of university administration, technological dynamic capabilities reflect the ability to meet students’ evolving digital literacy needs, respond to AI-related challenges and lead sustainable innovation. These are expressed through two main dimensions: technological administrative communication (ensuring transparency, support, and clarity about technology use) and technological administrative transformation (driving strategic shifts toward intelligent systems). These capabilities are crucial to enabling administrators to use AI not only for institutional efficiency but also for empowering students through digital literacy and innovation. AI applications like chatbots, intelligent tutoring systems, predictive analytics, and digital writing assistants help improve student outcomes [

40]. However, these benefits hinge on students’ awareness and critical engagement with such tools [

41,

42,

43,

44] and students’ awareness of technology use is shaped by factors such as institutional training, faculty support, and curricular integration [

45]. Without intentional efforts to raise awareness and develop competencies, the use of AI may exacerbate existing educational inequities rather than resolve them.

As AI becomes increasingly central to academic and administrative operations [

12,

46], universities must ensure that their digital transformation is inclusive, ethical, and sustainability oriented. Institutions lacking a foundational understanding of AI risk being left behind [

47]. Accordingly, this study adopts Dynamic Capabilities Theory to explore how the technological dynamic capabilities of university administration at Sultan Qaboos University influence students’ awareness of AI tools. Unlike technology adoption models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) or the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), which focus primarily on individual user acceptance, DCT offers a broader organizational perspective. It emphasizes how institutions can integrate, build, and reconfigure internal competencies in response to technological change, making it more suitable for analyzing institutional roles in shaping students’ exposure to and understanding of AI tools. Understanding this relationship is essential for ensuring that technological innovation supports the broader goals of education for sustainable development, digital equity, and future-ready learning, aims that align with the vision of SDG 4 for inclusive and equitable quality education for all.

The relationships between the identified capabilities, competencies, and dimensions are illustrated in

Figure 1, which presents a conceptual model summarizing the theoretical framework of the study. This framework directly informs the study’s design, guiding the construction of the measurement instrument, the grouping of scale items, and the interpretation of statistical findings.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Research Question 1

This research question examined the current level of technological dynamic capabilities within the university administration and students’ awareness of using generative AI tools in the educational context. The findings indicate that both the technological dynamic capabilities of the university administration and students’ awareness of using AI tools are at a moderate level. This suggests that Sultan Qaboos University has taken steps to respond to technological change, yet there appears to be substantial room for improvement, particularly in integrating AI technologies into educational and administrative practices.

The two sub-dimensions of dynamic capabilities (Technological Administrative Communication and Technological Administrative Transformation) were also found to be moderate, reflecting the university’s developing ability to adapt to and implement AI technologies in its processes. While this indicates some institutional readiness, it points to the need for more effective decision-making and strategic integration of AI to enhance educational quality and institutional competitiveness.

These dynamic capabilities are foundational for universities seeking to adapt to rapid digital shifts. As noted by Alshadoodee et al. [

50], activating such capabilities can be important to transforming traditional education into a modern digital environment, especially at the undergraduate level where students begin developing essential digital skills. Enhancing dynamic capabilities may support flexible learning environments, innovation and sustainable improvement by investing in digital infrastructure and integrating AI into both teaching and assessment.

The moderate level of students’ awareness in using generative AI tools also points to a generally positive trend, reflecting their growing engagement with emerging technologies. While some of this awareness may stem from the university’s technological environment, it is also shaped by external societal influences. This dual influence highlights a complex ecosystem of learning, where formal education intersects with informal digital literacy.

As ChatGPT and similar AI tools become increasingly prevalent in higher education [

51], students are gaining exposure to powerful AI applications that support interactive, personalized, and self-directed learning. Studies highlight the rapid spread of ChatGPT in educational contexts, reflecting a broader transformation in how students learn and engage with content [

52,

53].

However, as Sposato cautions, the integration of AI into academic environments is not without its complexities [

54]. Although AI technologies hold substantial promise for improving learning outcomes and expanding educational access, their integration into academic settings requires thoughtful consideration. Sposato emphasizes the need for a balanced approach that recognizes both the opportunities and limitations of AI while prioritizing the preservation of human-centered educational values.

In light of this, it is essential to recognize that students may not always use AI tools in ways that align with intended learning outcomes. To address this, greater institutional support is needed to guide the ethical and pedagogical use of AI. This includes targeted professional development for faculty members, who play a pivotal role in modeling responsible AI use. By equipping faculty members with the necessary skills and frameworks, universities can better support the effective educational integration of AI while upholding academic integrity.

5.2. Discussion of Research Question 2

This research question investigated the nature of the correlation between the university administration’s technological dynamic capabilities and students’ awareness of AI usage. The findings revealed a statistically significant positive but modest correlation between the scores of students on the overall University Administration’s Technological Dynamic Capabilities in AI Scale and their scores on the Synthetic Index of Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools, at a significance level of 0.01. This result indicates a statistically reliable but moderate association; as students perceive higher technological dynamic capabilities within their university administration, their awareness and use of AI tools tends to increase correspondingly.

These findings are consistent with prior research. Studies by Bates et al. and Chai et al. similarly demonstrated that when educational institutions actively build and leverage dynamic technological capabilities, they create environments that promote students’ awareness of AI applications [

55,

56]. This, in turn, enhances students’ motivation to engage with AI tools and develop related competencies. Kelly et al. also emphasized that the integration of AI within educational institutions encourages student acceptance of AI technologies, especially in the design and delivery of learning environments [

57]. This acceptance plays a key role in strengthening students’ motivation and readiness to use these tools effectively in their academic work. Similarly, Deng and Yu found that AI tools, particularly chatbot technologies, can enhance classroom interaction and overall learning experiences [

58]. These technologies do more than streamline educational processes; they enrich student engagement, boost motivation, and improve learning outcomes, all of which are crucial for success in higher education.

Our findings also align with Owens and Lilly, who noted that students’ intentions toward adopting educational technologies often reflect the quality and variety of learning experiences offered by their institutions throughout different academic stages [

59]. In other words, when universities invest in and demonstrate technological dynamic capabilities, they are more likely to influence students’ positive attitudes toward using AI. This result underscores the strategic role of university administrations in shaping students’ digital engagement. The direct correlation found in this study affirms that when institutions demonstrate strong technological dynamic capabilities, they are better positioned to support students’ awareness and informed use of AI tools in educational contexts.

5.3. Discussion of Research Question 3

This research question examined the predictive relationship between university administration’s technological dynamic capabilities and students’ awareness of AI tool usage, using simple linear regression analysis. The findings show that the technological dynamic capabilities of university administration significantly contribute to predicting students’ overall awareness of AI tools, accounting for 12.4% of the variance. Additionally, these capabilities significantly predicted two specific dimensions of AI awareness: the effectiveness of AI tool use and faculty proficiency in AI, with contribution rates of 21.8% and 1.5%, respectively.

These results highlight the crucial role of institutional adaptability in cultivating digital awareness among students. Researchers attribute this to the importance of university administrations possessing dynamic capabilities that enable them to respond proactively to technological changes in the educational landscape. Such responsiveness fosters an environment where students are more aware of, and prepared to engage with, emerging digital tools. This finding is consistent with Nadia’s work, which emphasized the necessity for institutions to adapt quickly to change and to approach it with creativity and innovation [

60]. The university administration’s ability to implement best practices for using AI in classrooms represents a form of institutional adaptation that not only modernizes pedagogy but also equips students with essential competencies for the evolving labor market. This perspective aligns with the findings of Hernández-Linares who stressed the importance of institutional sensing and responsiveness in developing organizational capabilities, particularly in the context of staff preparedness [

61].

However, while the predictive contribution to students’ perception of faculty proficiency in AI was statistically significant, it was relatively limited at 1.5%, suggesting that faculty members may currently lack sufficient readiness or training to integrate AI tools effectively into their teaching. This highlights a key developmental need: enhancing the university’s dynamic capability in faculty professional development, especially around the pedagogical integration of AI applications. Strengthening this area could increase faculty confidence and competence in using AI, thereby reinforcing student awareness and engagement.

Moreover, the broader implications of AI awareness extend into the motivational domain. When students recognize the relevance and utility of AI technologies in their academic and professional lives, their acceptance of these tools increases, positively influencing their motivation to learn. Rozek et al. noted that students’ acceptance of educational technologies like AI can act as a catalyst for deeper learning, particularly when students understand the practical value of these tools [

62]. Similarly, Upadhyay et al. proposed an AI acceptance model that identifies performance expectations, openness to experience, social influence, enjoyment, and productivity as key drivers of student motivation to adopt AI tools [

63]. These findings, therefore, highlight the importance of strengthening the dynamic technological capabilities of university administrations, not only for advancing institutional innovation but also for enhancing students’ digital readiness and active engagement with AI tools.

Although the regression model yielded a statistically significant result (R2 = 0.124), the proportion of variance explained is relatively small. This suggests that while dynamic capabilities, specifically seizing and reconfiguring, contribute to students’ awareness of AI tools, other unmeasured factors may also play a substantial role. Moreover, it is important to note that several predictors did not reach statistical significance. These non-significant results highlight the complexity of the phenomenon and suggest that awareness of AI tools among students may be influenced by variables beyond the scope of this study, such as individual digital literacy, curriculum exposure or institutional culture. Finally, the exclusion of the “Sensing” dimension may have narrowed the operationalization of dynamic capabilities. As such, interpretations should be confined to the dimensions assessed, and future research is encouraged to explore sensing in contexts where its indicators are more observable and meaningful to participants.

5.4. Conceptual Contribution

This study contributes to the literature on Dynamic Capabilities Theory by applying it to the context of AI literacy in higher education, particularly from the perspective of students rather than institutional actors. The findings confirm the relevance of the “Seizing” and “Reconfiguring” dimensions in shaping students’ awareness of AI tools, while the exclusion of “Sensing” highlights the need to recontextualize this dimension when applied outside organizational leadership. This suggests a potential student-centered adaptation of DCT in educational contexts, where environmental scanning may be less salient than internal capability development and resource restructuring.

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

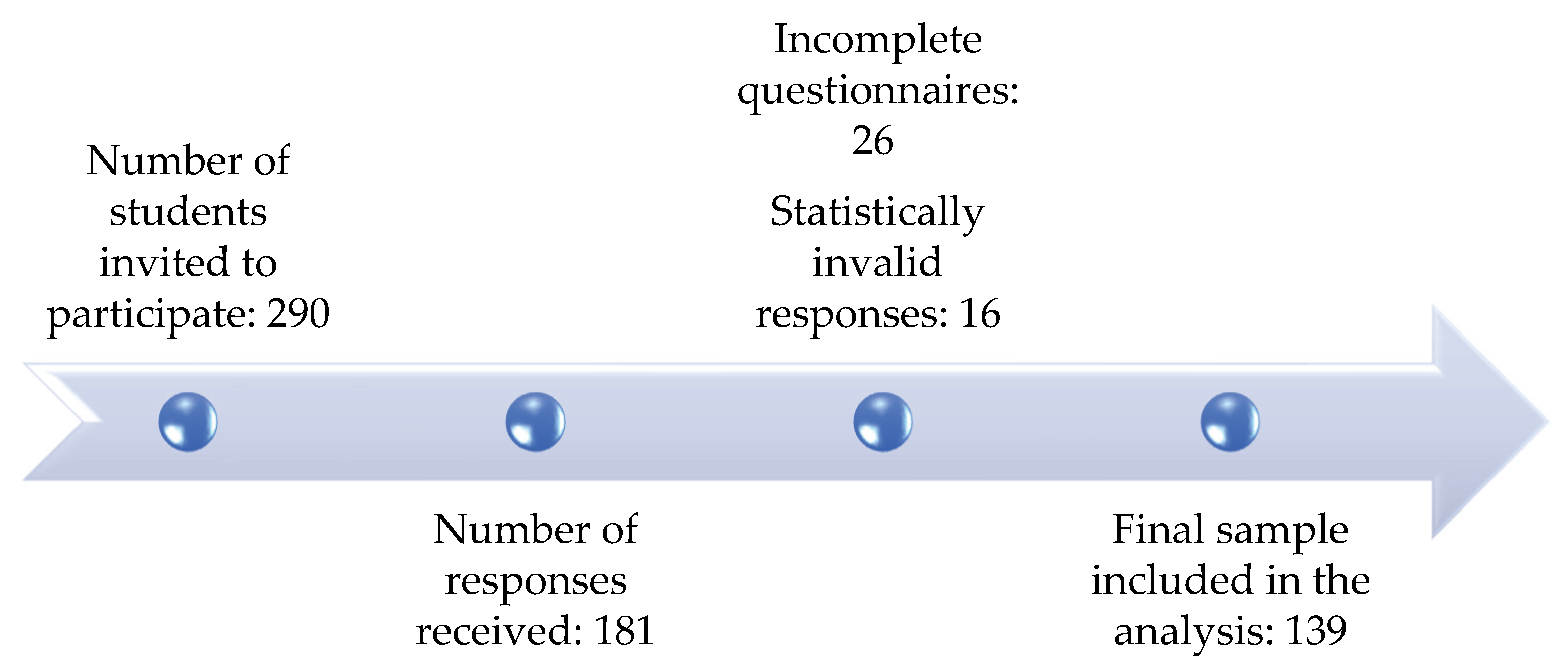

While this study offers valuable insights into how university administration’s technological dynamic capabilities relate to students’ awareness of AI, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample was limited to students from the College of Education at Sultan Qaboos University, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other disciplines or institutional contexts. Moreover, a purposive sampling approach was employed, which, while appropriate for exploratory research, may limit the representativeness of the sample. The cross-sectional design of the study further restricts the ability to draw causal inferences or observe changes over time. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, including social desirability effects and subjective variability in how students interpret and report their awareness of AI.

Future research could benefit from mixed methods approaches that combine quantitative data with interviews or focus groups to provide deeper insight into students’ experiences and interpretations of AI integration. Triangulating data sources, such as institutional policy reviews, classroom observations and student performance data, could also strengthen the validity of findings and offer a more holistic understanding of institutional readiness. In addition, experimental designs may help establish causal relationships between specific dynamic capability interventions (e.g., AI-focused faculty training or curriculum redesign) and measurable changes in student AI literacy or engagement.

Importantly, the findings suggest new directions for inclusive, equity-focused research. Future studies should examine how technological dynamic capabilities influence AI awareness among students with special needs, a group often underserved in digital transformation discourse. Investigating how university administrations can adapt their technological strategies to foster accessibility and inclusion would support the broader goals of educational equity and SDG 4.

Further, the study highlights gaps in faculty preparedness for AI integration. As such, future research might design and evaluate AI-supported professional development programs to build adaptive leadership and teaching capacity within university administrations. Research could also explore how AI tools themselves, such as predictive analytics or intelligent decision systems, can enhance dynamic capabilities and support strategic planning, resource optimization, and more personalized support for diverse learners. These research efforts, combined with practical initiatives such as developing AI-integrated curricula, fostering adaptive learning environments, and organizing awareness-raising workshops, can collectively contribute to a more inclusive and technologically progressive educational ecosystem.