1. Introduction

Effective water governance has become a cornerstone of sustainable development and climate adaptation in Europe. As water systems face growing stress from climate change, demographic shifts, and aging infrastructure, the capacity of institutions to manage water equitably and efficiently has never been more critical. Governance, once seen as a background administrative process, is now recognized as a key determinant of freshwater security—defined not only as access to water resources but also the ability to manage risks, ensure affordability, and support long-term ecosystem resilience.

According to the European Environment Agency, nearly 20% of EU land and 30% of its population are affected by drought or water scarcity each year, with Mediterranean regions expected to experience up to 40% reductions in summer river flows by 2050 [

1]. In response, the European Union has launched major initiatives—including the Water Framework Directive (WFD) [

2], the European Green Deal [

3], the 2021 Climate Adaptation Strategy [

4], and SDG Indicator 6.5.1 [

5]—to promote integrated, climate-resilient, and inclusive water governance systems. Despite this progress, substantial governance gaps remain—particularly in Southern Europe—where fragmented institutional structures, limited implementation capacity, and uneven territorial inclusion undermine policy effectiveness [

6,

7]. Recent studies underscore the urgency of aligning water governance with climate adaptation, highlighting persistent institutional fragmentation and inequitable resource access in Southern Europe [

8,

9].

By contrast, Nordic countries such as Denmark and Finland demonstrate more mature governance models, grounded in institutional coherence, independent regulation, and participatory planning [

10,

11]. These models offer potential lessons for regions struggling to align water governance with sustainability and equity goals. Yet, transferring institutional practices across contexts raises important questions of feasibility, adaptability, and institutional fit [

12,

13,

14].

To address these challenges, this study introduces the Water Governance Maturity Index (WGMI)—a diagnostic, document-based tool that evaluates national water governance across five critical dimensions: (1) institutional and regulatory capacity, (2) operational effectiveness, (3) environmental ambition, (4) social and territorial equity, and (5) climate adaptation integration. Unlike generic indicators, the WGMI translates complex governance concepts—such as independence, coordination, and justice—into observable, measurable benchmarks.

This article addresses the following research questions:

- 1.

How do governance mechanisms—such as regulatory independence, stakeholder participation, and equitable resource allocation—differ between Nordic and Southern European countries?

- 2.

What context-sensitive lessons from Nordic models can enhance institutional reform, climate adaptation, and social equity in Southern European water governance?

Using content analysis of 47 national-level documents—including water strategies, river basin plans, and regulatory frameworks—the WGMI is applied to eight EU countries (four Nordic and four Southern). The goal is to provide a replicable framework for comparative assessment and to generate actionable insights for policymakers seeking to strengthen water governance in line with Europe’s just resilience agenda.

2. Literature Review

The literature on water governance spans institutional design, climate adaptation, equity, and policy transfer, offering robust theoretical frameworks but revealing persistent gaps in their practical application. The analysis informs the WGMI’s design, which seeks to bridge theory and practice through measurable indicators, while acknowledging areas that require further empirical investigation.

2.1. Institutional Capacity in Water Governance

The EU Water Framework Directive has shaped governance standards and promoted institutional convergence across member states [

15]. Consequently, water governance has evolved from a purely technical challenge to one of institutional complexity, emphasizing the importance of coordination and mandate clarity [

16,

17]. In this context, the OECD Principles highlight regulatory independence and inter-agency coherence as key components of adaptive water management [

18]. Moreover, Nordic countries illustrate the benefits of professionalized civil services that facilitate policy continuity and institutional learning [

19].

However, these assumptions often rest on idealized bureaucratic models that are difficult to replicate in politically fragmented or resource-constrained contexts. Specifically, in Southern Europe, overlapping mandates, political interference, and unstable funding compromise institutional resilience [

20,

21]. Even where bureaucratic stability exists, its effectiveness is frequently undermined by insufficient training and financial capacity [

22,

23]. As a result, operational efficiency varies widely across Europe, with Southern countries facing persistent problems related to underfunded agencies and inconsistent monitoring frameworks [

24,

25]. Moreover, there is limited research on how institutional capacity can be cultivated in decentralized systems where regional inequalities prevail [

26]. While the WGMI’s document-based indicators focus on mandate clarity and coordination, they may fail to capture informal governance arrangements that are essential in fragmented systems [

27]. Therefore, future studies should address how local knowledge and informal institutions contribute to water governance in contexts where formal mechanisms are insufficient.

2.2. Climate Adaptation and Multilevel Coordination

Climate variability—exemplified by droughts affecting 20% of EU territory annually—has intensified the need for adaptive governance [

28]. Consequently, polycentric governance models, which emphasize decentralization and overlapping authority, are widely praised for fostering institutional learning and resilience [

29,

30]. In particular, Ostrom’s work supports the idea that distributed systems are more responsive to climate stress [

31]. Thus, Nordic countries are often cited as successful cases of integrated climate and water governance [

32]. Nevertheless, despite their theoretical appeal, real-world application of these models in Southern Europe is hindered by fragmented administrative structures and resource imbalances [

33]. Vertical integration remains weak, and policy coordination between water and climate agendas is often superficial [

34,

35]. Although Nordic countries benefit from institutional trust and cross-sectoral planning, these enabling conditions are frequently absent in Southern settings [

36]. As a result, practical guidance on scaling adaptive governance in resource-constrained contexts remains scarce [

37,

38]. In addition, aquifer mismanagement and groundwater vulnerability further exacerbate adaptation deficits in the Mediterranean [

39]. Furthermore, non-state actors—such as NGOs and local communities—are underrepresented in the adaptation literature, despite their potential to enhance resilience [

40].

Strengthening science-policy integration is viewed as critical; however, current governance structures remain too rigid to respond effectively to evolving risks [

41,

42,

43]. While the WGMI includes climate adaptation indicators [

44], its formal approach may overlook informal or grassroots responses. Therefore, future research should investigate hybrid models and locally driven adaptation practices, especially in vulnerable regions [

45,

46,

47].

2.3. Equity, Justice, and Territorial Inclusion

Equity is central to water governance, encompassing affordability, participatory access, and territorial fairness [

48]. Accordingly, Northern European countries like Finland demonstrate strong equity outcomes through universal service guarantees and participatory frameworks [

49]. Nevertheless, persistent disparities exist in Southern Europe, particularly for rural and marginalized communities where service quality and affordability are lacking [

50]. Political ecology perspectives highlight that governance systems often reinforce structural inequalities, benefiting dominant actors such as utilities or urban elites, while excluding low-income or minority stakeholders [

51,

52,

53,

54]. The literature on transformative justice is rich in critique, yet it remains vague on implementation strategies [

55,

56]. Although the WGMI includes metrics on inclusion, participation, and affordability [

57], these may oversimplify intersectional issues like gender or ethnicity [

58,

59]. Therefore, participatory and co-produced research methods are needed to expose these nuances and design governance models that better reflect lived experiences [

60].

2.4. Context-Specific Policy Transfer

Nordic governance systems are often held up as benchmarks due to their coherence, transparency, and effectiveness [

61]. In line with this, policy transfer literature emphasizes the importance of institutional learning and structured diagnostics like the WGMI to facilitate reform [

62,

63]. However, successful transfer depends heavily on institutional compatibility and political context [

10,

11]. Southern European systems often face fiscal constraints, legal fragmentation, and short electoral cycles that limit reform capacity [

6,

26,

32]. Moreover, practical applications of policy transfer often neglect civic resistance and informal practices that shape governance on the ground [

40]. Moreover, empirical studies on how to adapt governance models to decentralized or volatile environments remain limited [

59]. While the WGMI offers a standardized tool for benchmarking governance maturity [

25], it may underrepresent soft variables such as trust, local innovation, and civic engagement [

22,

39]. Although content analysis methods [

9,

45] provide comparability, they should be supplemented with flexible, context-aware frameworks. Consequently, future research should prioritize hybrid transfer models and longitudinal assessments to understand the long-term impacts of reform [

33].

3. Data and Methods

This study introduces the Water Governance Maturity Index (WGMI), a multi-criteria assessment tool designed to evaluate the structural and functional maturity of national water governance systems. The WGMI was applied to eight European countries: four Nordic (Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Norway) and four Southern (Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece). These countries were selected to represent contrasting governance paradigms within the EU, based on diversity in administrative traditions, regional climatic conditions, and the availability of national policy documentation. This selection provides a robust North–South comparison, allowing the study to capture a broad spectrum of institutional configurations and policy environments.

3.1. WGMI Framework: Dimensions and Indicators

The WGMI assesses governance across five core dimensions, each composed of two indicators (

Table 1). These indicators were selected through a multi-step process involving literature review and alignment with international policy frameworks such as the OECD Principles on Water Governance [

7] and the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) [

2]. Each indicator reflects a specific aspect of governance maturity—ranging from institutional capacity to equity and climate adaptation—and captures observable features in official documents. The equity dimension prioritizes distributive aspects (affordability and territorial inclusion) due to their measurability in policy documents, though future iterations may incorporate procedural justice metrics, such as public participation, to address broader equity concerns [

23].

The indicators were weighted equally to avoid normative bias and to ensure comparability across countries. This unweighted approach allows for clearer identification of strengths and weaknesses by governance dimension. The selection and refinement of indicators involved review to ensure institutional fit, indicator clarity, and policy relevance.

3.2. Scoring Methodology

Each indicator was rated on a 0–4 ordinal scale based on documentary evidence. The scoring criteria were defined to reflect increasing levels of institutionalization, coverage, and implementation.

Table 2 presents the WGMI scoring scale, which uses a 0–4 ordinal system to classify governance maturity based on observable evidence, accompanied by country-specific examples for each level.

Scores for each dimension were calculated as the average of its two indicators. The overall WGMI score is the unweighted mean of the five dimension scores.

Maturity categories:

0–1.0: Emerging

1.1–2.0: Developing

2.1–3.0: Advanced

3.1–4.0: Model

3.3. Document Selection and Coding Protocol

A total of 47 national-level documents were analyzed, including water strategies, River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs), sectoral laws, EU compliance reports, and OECD/EEA country profiles. Inclusion criteria required documents to be official, publicly available, and published within the past ten years. Documents were systematically sourced from national government websites, EU repositories (e.g., EIONET), and academic databases (e.g., Scopus) using keywords such as ‘water governance,’ ‘river basin management,’ and ‘climate adaptation.’ Priority was given to documents published between 2015 and 2025, ensuring relevance and consistency across countries.

Whenever possible, regional representativeness was ensured by including basin-level plans for major watersheds. A complete list of source documents, with publication dates and institutional origin, is provided in

Appendix C. To address disparities in document length, coverage, and administrative detail, coders applied a normalization protocol: partial references were triangulated with secondary sources, and missing information was flagged to avoid over-penalization. Direct quotes and legal excerpts were used to support indicator scoring. For instance, Greece’s missing River Basin Management Plans for 40% of water bodies were supplemented with EU compliance reports and regional water authority data to ensure fair scoring [

2].

3.4. Intercoder Training and Linguistic Adaptation

To guarantee consistency in the application of the index, two independent coders conducted the coding of documents using a detailed protocol. This procedure allowed for the assessment of inter-coder reliability of the results. Although no formal pilot tests or structured expert consultations were performed, the methodology builds upon internationally recognized frameworks such as the OECD Principles and the EU Water Framework Directive. The absence of these steps is acknowledged as a limitation, and future research is encouraged to incorporate additional validation to enhance the robustness of the index. Disagreements between coders were resolved through consensus, considering the specific legal and institutional contexts of each country.

3.5. Reliability Measures and Cultural Limitations

Inter-coder reliability reached a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of 0.82, indicating strong agreement. However, due to the variability of legal language and institutional logics across countries, coders were instructed to apply qualitative judgment alongside the coding protocol to improve interpretive accuracy, especially in decentralized or hybrid governance systems.

3.6. WGMI Indicator Examples by Dimension

Table 3 provides illustrative examples of how indicators were interpreted and scored across dimensions.

3.7. Validity and Transparency Measures

To ensure replicability and methodological transparency, the WGMI framework was developed using clearly defined criteria, systematic document sourcing, and a structured coding protocol. Scoring was based on publicly available evidence and triangulated with external benchmarks such as SDG 6.5.1 and WFD compliance reports.

WGMI scores showed strong alignment with existing integrated water governance indicators (r = 0.79), reinforcing the internal coherence of the index. All coding rubrics, scoring criteria, country-level evidence tables, and aggregated statistics are provided in

Appendix A,

Appendix B,

Appendix C,

Appendix D,

Appendix E. Key legal excerpts and public document links are included in Annex C to support transparency and reproducibility.

4. Results

4.1. Governance Maturity Scores: North–South Divide

The Water Governance Maturity Index (WGMI) confirms a persistent governance divide across Europe. Nordic countries consistently outperform Southern counterparts. Denmark (39.0), Finland (36.9), Norway (33.9), and Sweden (33.2) all scored within the “Advanced” or “Model” maturity categories, while Portugal (24.7) and Spain (23.1) remained in the “Developing” range. Italy (17.3) and Greece (14.1) fell within the “Emerging” category. A detailed breakdown of country-level scores, indicators, sources, and excerpts is available in Annex B, included for transparency and replicability.

4.2. Operational Indicators: Access, Monitoring, Pricing, and Innovation

Contextual indicators reinforce the WGMI results. Access to safe drinking water exceeds 99% in all Nordic countries, with Denmark and Sweden reaching full coverage. Environmental monitoring systems are robust: Denmark monitors over 80% of surface water bodies in real time, using digital dashboards for decision-making. Water pricing data reveals stark differences. Nordic countries report average household costs between EUR 250 and EUR 400 per year, reflecting full-cost recovery paired with strong quality guarantees and equity mechanisms. In contrast, water prices in Portugal (EUR 90/year) and Italy (EUR 160–EUR 220/year depending on region) are significantly lower but correspond with fragmented services. Nordic countries also lead in innovation, with high volumes of registered water-related patents, particularly in smart metering, wastewater reuse, and stormwater management. Southern countries face persistent structural gaps. Greece lacks River Basin Management Plans for nearly 40% of water bodies. Italy shows strong regulatory design but weak implementation capacity, especially in the South. Portugal and Spain demonstrate better institutional alignment, but execution remains constrained by administrative fragmentation and underfunding.

4.3. Performance by Governance Dimension

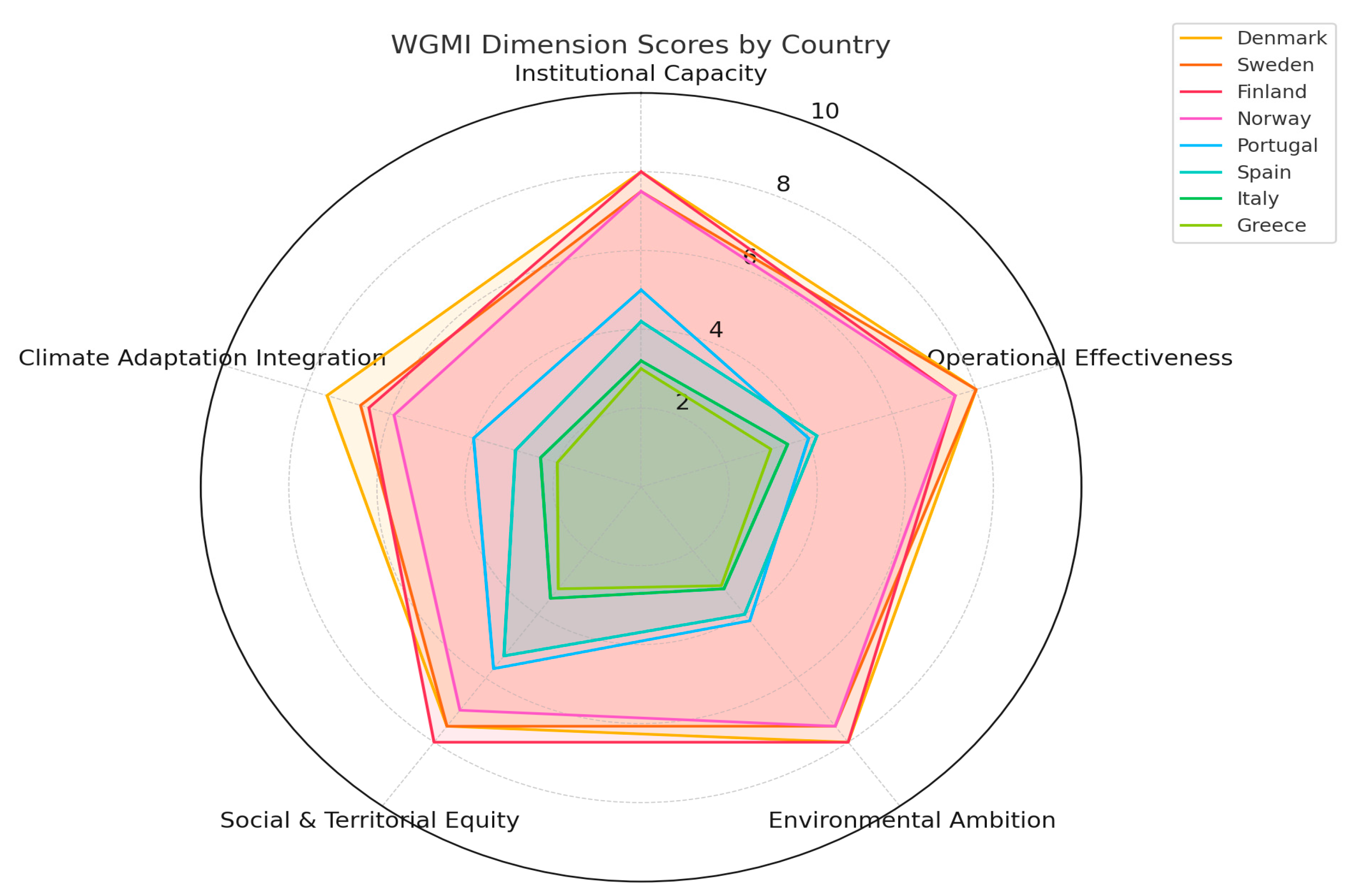

Decomposing the WGMI by dimension reveals further asymmetries. Denmark and Finland consistently perform best in institutional capacity, environmental ambition, and social equity. Sweden excels in operational effectiveness and climate adaptation. Southern countries display uneven performance: Portugal scores relatively well on equity but lags in effectiveness and monitoring. Spain shows moderate ambition but suffers from institutional incoherence. Italy and Greece underperform across all dimensions.

Institutional capacity is reinforced in Denmark by a strong, independent national regulator. Spain, by contrast, struggles with overlapping competencies among regional authorities. Operational effectiveness is high in Sweden and Finland, which rely on automated planning cycles and integrated monitoring. Portugal and Greece show weak enforcement and bureaucratic inertia. Environmental ambition is visible in Denmark and Finland’s SMART targets and enforcement tools, while Italy and Spain lack enforceable timelines. Social equity is safeguarded in Nordic countries through targeted subsidies and universal coverage. Portugal has pro-equity mechanisms in law, but implementation gaps remain, especially in interior regions. Italy and Greece lack systemic mechanisms beyond national subsidies. Climate adaptation is mainstreamed in Finland and Sweden through scenario-based planning. In Southern countries, references to climate risk exist in strategic documents but with limited execution.

4.4. Visual and Statistical Comparisons

Figure 1 presents a radar chart showing average scores (0–10) by governance dimension.

Nordic countries display consistent, high-level performance across all dimensions. Southern countries exhibit fragmented profiles, with relative strength in social equity.

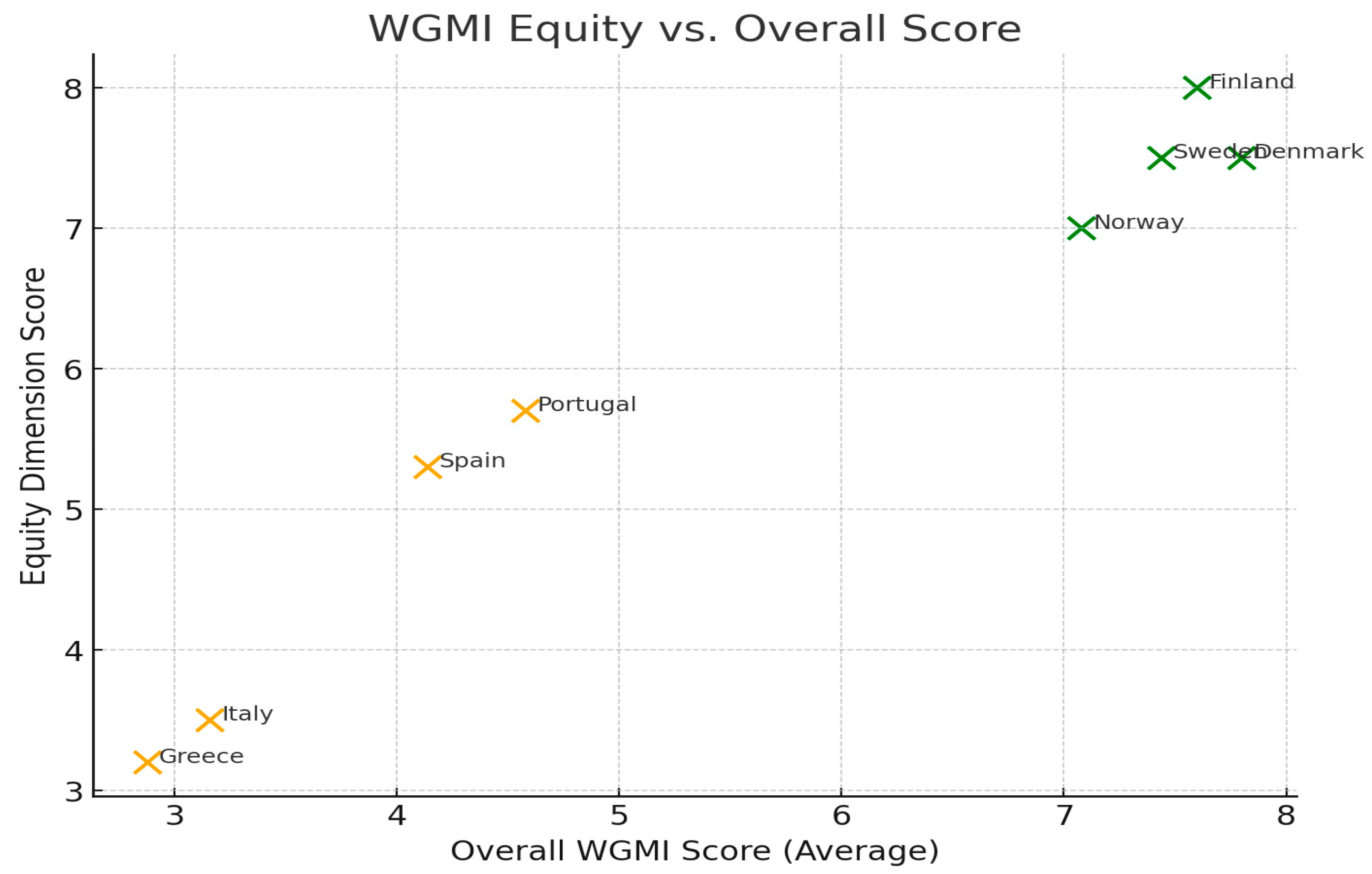

Figure 2 plots WGMI overall scores against equity dimension scores.

Nordic countries cluster in the top-right quadrant, with high maturity and strong equity; Portugal and Spain lie in the mid-range, while Italy and Greece occupy the bottom-left quadrant, reflecting multiple governance deficits.

Descriptive statistics confirm the divide. Nordic countries average over 7.5 across all dimensions, while Southern countries average below 4.5. Standard deviations suggest greater variation within the South, especially for institutional capacity and climate adaptation (Annex C). These patterns suggest that stronger governance systems are associated with more balanced, equitable performance profiles.

4.5. Country Snapshots: Portugal and Spain

Portugal’s PENSAARP 2030 plan outlines reuse targets, affordability measures, and adaptive infrastructure goals. Yet implementation varies significantly across regions. Licensing in rural areas remains restricted. Text mining of national planning documents reveals low occurrence of terms such as “consultation” and “public involvement,” suggesting limited procedural inclusion. In Spain, the Groundwater Action Plan [

64] expands public consultation timelines and integrates climate goals, including nitrate control and aquifer recharge. However, regional uptake is uneven. Catalonia and the Canary Islands face funding shortages and institutional misalignment. The cancellation of the Ebro River transfer project illustrates political instability that hampers long-term planning. Both cases highlight a broader pattern: strong national policy design does not guarantee effective implementation when administrative fragmentation and accountability gaps persist.

4.6. Subnational and Structural Variability

Despite the north–south pattern, significant within-country variation exists. In Italy, northern regions outperform the South in monitoring and participation. Spain features well-designed participatory mechanisms, but their operationalization suffers from fiscal decentralization. Even within the North, Norway scores slightly lower due to uneven monitoring across basins and a more decentralized institutional setup.

Structural factors influencing performance include fiscal fragmentation (e.g., Spain), austerity constraints (e.g., Greece), and limited administrative capacity (e.g., Italy and Portugal). These underlying constraints shape not only the maturity of governance structures but also their ability to respond to environmental pressures and social demands.

5. Discussion

5.1. Institutionalizing Reform: Lessons from Nordic Models

The WGMI reaffirms that institutional coherence, regulatory independence, and administrative continuity are key pillars of effective water governance. Denmark, Sweden, and Finland exemplify systems where national oversight, strong river basin coordination, and stable public administration underpin high performance [

15,

22]. Intra-regional variations, such as Italy’s stronger northern monitoring systems or Norway’s uneven basin coverage, highlight the need for tailored reforms within countries [

32]. However, as policy transfer theory cautions, these models cannot be transplanted wholesale. Reform success depends on institutional fit—that is, alignment with existing legal frameworks, administrative traditions, and political incentives [

10,

25].

Key recommendations include strengthening the institutional foundations of water governance through targeted reforms. First, establishing independent regulatory bodies is essential in countries such as Italy and Greece, where governance is currently undermined by fragmented mandates and persistent political interference. In this regard, the ERSAR model in Portugal offers a valuable example, as it successfully separates technical oversight from political cycles, thereby ensuring greater stability and credibility. Furthermore, implementing civil service reforms aimed at reducing turnover and enhancing institutional memory would reinforce policy continuity and administrative capacity. These efforts should be strategically aligned with broader EU frameworks, particularly through public sector modernization programs supported by the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) [

3].

Limits of Policy Transfer: Contextual Barriers

Although Nordic governance models are frequently cited as best practices in water management, their direct transfer to other contexts faces significant limitations. These barriers are rooted in fundamental differences in political culture, administrative capacity, and civic engagement.

- (a)

Political Culture: Nordic countries are characterized by high levels of institutional trust and a tradition of consensus-driven policymaking. In contrast, many Southern European countries experience greater political polarization and frequent changes in government, which disrupt continuity and long-term planning in water governance.

- (b)

Administrative Capacity: Finland and Denmark benefit from well-established, professionalized civil services and autonomous regulatory agencies. Conversely, Southern countries often struggle with fragmented institutional mandates and agencies that operate under severe resource constraints, limiting their effectiveness and adaptability.

- (c)

Civic Engagement: Public participation is deeply embedded in Nordic systems, facilitated by basin councils and digital platforms that promote transparent, inclusive governance. By comparison, in countries such as Portugal and Greece, participatory mechanisms tend to be either underutilized or implemented in a formalistic manner, often lacking meaningful citizen involvement in decision-making processes. A summary of these differences is shown in

Table 4 below.

Water pricing significantly influences system effectiveness and sustainability, with Nordic countries’ higher prices (EUR 3.60–EUR 9.50/m

3 in Sweden and Denmark) enabling robust infrastructure investment and full cost recovery, while lower prices in Southern Europe (EUR 1.10–EUR 2.60/m

3 in Portugal, Greece, and Italy) often correlate with underfunded systems and fragmented services [

3].

5.2. Policy Transfer and Institutional Fit: Pathways and Pitfalls

The literature on policy transfer distinguishes between “lesson-drawing,” understood as the selective adoption of external models [

59], and more nuanced processes of strategic adaptation to local contexts. For institutional reforms to succeed, three core conditions must be met: institutional fit—ensuring compatibility with existing legal and administrative traditions; political feasibility—aligning reforms with domestic power structures; and economic incentives—establishing supportive financing frameworks. Practical examples illustrate these dynamics. Portugal’s adoption of the ERSAR model, for instance, was facilitated by its congruence with national legal traditions and the incentives provided through EU integration. By contrast, Greece has faced persistent challenges in implementing basin-level coordination mechanisms, largely due to its limited regional autonomy and fiscal constraints, which have constrained both policy design and enforcement.

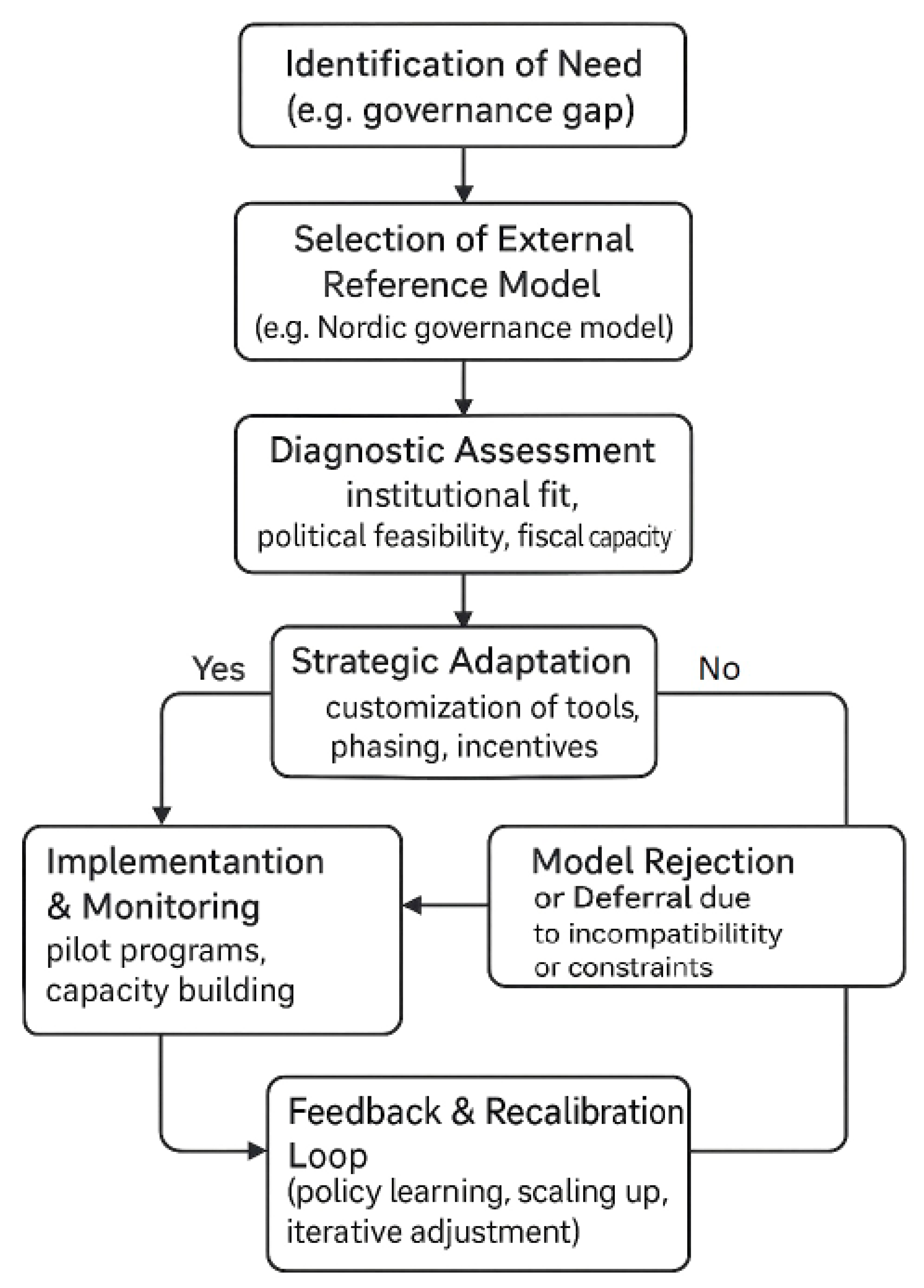

Figure 3 illustrates the typical pathway of policy transfer, highlighting diagnostic assessments, strategic adaptation, and feedback loops for institutional learning.

The figure outlines the typical policy transfer pathway from best practices to contextual adaptation. The process begins with the identification of a governance need, followed by the selection of an external reference model—such as Nordic regulatory frameworks. A diagnostic assessment then evaluates institutional fit, political feasibility, and fiscal capacity. If these conditions are met, the process moves toward strategic adaptation, involving context-sensitive customization of policies and tools. This is followed by implementation and monitoring, often supported by external funding mechanisms such as the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility. Feedback loops ensure continuous policy learning and recalibration. In cases where diagnostic conditions are not met, the model may be rejected or its adoption deferred. Reform is inherently non-linear, and institutional change requires iterative learning and alignment with domestic governance structures.

5.3. Deepening the Equity Dimension: From Access to Participation

Quantitative analysis reveals that Southern countries’ equity scores—such as Greece (4.4) and Italy (5.0)—consistently fall below the Nordic averages (7.0–8.0), as shown in

Appendix D. This disparity reflects limited rural service coverage and weak participatory mechanisms in the South. While the WGMI primarily emphasizes accessibility and territorial inclusion, a broader understanding of equity must also include procedural justice and opportunities for public voice.

This gap underscores the need to unpack equity into its key dimensions:

- (a)

Accessibility: Northern countries like Finland and Denmark provide near-universal access, supported by affordability guarantees. In contrast, rural areas in countries such as Greece and Portugal continue to experience significant service gaps.

- (b)

Rural Coverage: Some Southern strategies aim to address territorial imbalances—for example, Portugal’s water reuse initiatives and Italy’s regional tariff structures. However, both lack consistent monitoring and enforcement, which undermines their long-term effectiveness.

- (c)

Procedural Justice and Participation: This remains a particularly critical weakness. While Spanish River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) include provisions for public consultation, actual stakeholder influence is limited. WGMI scoring also indicates minimal emphasis on “citizen engagement” or “participatory design” across many Southern plans.

Thus, future research should explore participation mechanisms in greater depth, combining content analysis with stakeholder interviews. In parallel, WGMI indicators should be expanded to incorporate measures of procedural justice and community engagement.

5.4. Financing as Leverage: Incentivizing Institutional Maturity

Governance reform depends on adequate and well-targeted financing. Nordic countries achieve near full cost recovery, not by eliminating subsidies but by strategically linking them to performance outcomes [

35]. In contrast, EU funds in Southern Europe—such as RRF and Cohesion Policy investments—often remain disconnected from institutional reform [

36].

Key recommendations:

Tie national and EU funding to governance benchmarks such as real-time monitoring systems, inter-agency coordination bodies, and equitable tariff structures.

Scale up financial instruments like green bonds and performance-linked subsidies targeting low-income or climate-vulnerable regions.

Align funding streams with institutional reforms through mechanisms like the Just Transition Fund and EU Climate Social Fund.

5.5. From Evaluation to Implementation: WGMI as a Policy Tool

The WGMI bridges academic insights and policymaking needs. Unlike generic indicators such as SDG 6.5.1 [

4], it offers document-based, dimension-specific, and replicable evaluation. It translates complex governance concepts—such as transparency, coordination, and resilience—into operational benchmarks [

37].

Applications include:

Complementing assessments under the revised Water Framework Directive and EU Adaptation Strategy [

3,

38,

39,

40].

Diagnosing governance bottlenecks and tracking national reform trajectories.

Guiding investment decisions by linking EU funds and climate finance to demonstrable improvements in governance maturity.

One practical use case: national agencies or EU directorates could require WGMI-based self-assessments in project submissions under the RRF or Just Transition funding calls. This would promote evidence-based investment and ensure alignment with long-term sustainability goals.

6. Conclusions

This study provides new evidence of the persistent divide in water governance maturity between Northern and Southern Europe. By introducing and applying the Water Governance Maturity Index (WGMI) to eight countries, we translated abstract governance principles into a structured, evidence-based assessment framework. The results reveal not only institutional contrasts—such as the coherence and continuity of Nordic systems versus the fragmentation prevalent in Southern countries—but also systemic weaknesses in climate adaptation, equity, and operational capacity. These findings matter: governance, though often overlooked, is a key determinant of climate resilience, public trust, and inclusive development. As Europe confronts escalating water stress and deepening territorial inequality, strengthening governance must become a central objective—not a secondary administrative concern—in achieving the EU’s Just Transition, Green Deal, and Climate Adaptation Strategy.

The WGMI contributes to this effort in two distinct ways. First, it offers a replicable diagnostic tool that enables national agencies, EU institutions, and civil society actors to identify governance gaps, benchmark progress, and inform reform priorities. Second, it highlights actionable institutional features—such as independent regulation, basin-level coordination, and participatory planning—that can guide legal frameworks and resource allocation.

At the same time, some limitations merit reflection. The WGMI relies on publicly available documents and secondary data, which may introduce bias due to differences in reporting quality, transparency, and administrative documentation across countries. For instance, nations with more accessible or detailed planning archives may appear to perform better—not necessarily because of stronger governance, but due to higher data visibility. This underscores the importance of complementing document-based analysis with field research to validate scoring and increase contextual sensitivity. Beyond documentation bias, interpretive challenges arise from varying legal terminologies and administrative cultures, particularly in decentralized systems like Spain’s, where regional differences complicate coding [

32]. Missing data, such as Greece’s incomplete RBMPs, may also undervalue governance efforts, necessitating qualitative validation [

2].

Future work should therefore focus on empirical validation through interviews with water managers, regulators, and user groups, as well as field testing in regions with limited documentation. Integrating real-time indicators—such as water quality, service disruptions, or public complaints—could improve the tool’s responsiveness and external validity.

Although developed for the EU context, the WGMI holds potential for broader application. However, this potential must be approached with caution. Pilot studies in Eastern Europe, Latin America, or sub-Saharan Africa could help assess its relevance across varied institutional landscapes. For example, applying the WGMI to Brazil’s São Francisco River Basin could test its adaptability to decentralized, resource-constrained contexts, adjusting indicators for local governance structures [

22].

In highly decentralized or resource-constrained settings, adjustments to the scoring framework may be necessary. Ultimately, improving water governance is not just a technical or institutional task—it is a strategic imperative for building resilient, equitable, and climate-ready societies. Tools like the WGMI can support this transition, moving countries from fragmented policy intentions toward coherent and inclusive implementation.