1. Introduction

The global sustainability crisis requires profound transformations in how organizations operate, with growing recognition that incremental approaches are insufficient to address mounting environmental and social challenges [

1,

2]. Despite increasing commitment to sustainability among organizations across sectors, a persistent gap remains between sustainability aspirations and substantive action [

3,

4]. This gap presents both a practical problem and a theoretical puzzle: why do organizations struggle to translate sustainability commitments into transformative change, and what capabilities and mechanisms enable some organizations to overcome these challenges?

This research addresses this puzzle by investigating how organizations bridge the sustainability rhetoric–action gap through developing specific capabilities and integration mechanisms that enable substantive transformations. We move beyond existing research that has identified this gap [

5,

6] to examine the specific organizational practices and contextual conditions that allow organizations to overcome it.

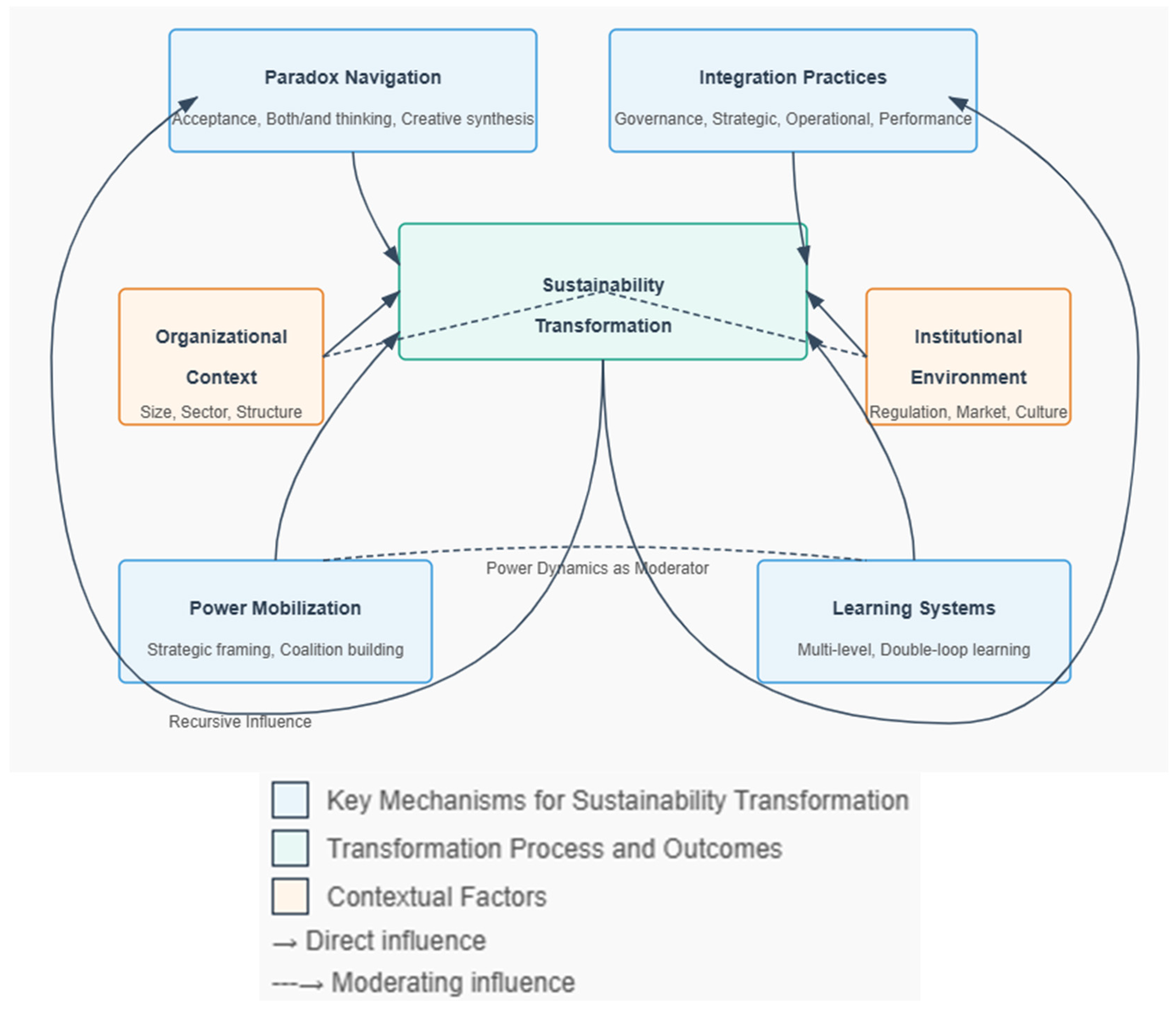

Our study is primarily grounded in paradox theory [

7], which provides a powerful lens for understanding how organizations navigate the competing yet interdependent demands inherent in sustainability transformation. We complement this with insights from organizational learning theory [

8], institutional logics [

9], and power dynamics [

10] to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework that explains the capabilities and mechanisms facilitating substantive sustainability transformations.

Our theoretical framework also draws on systems thinking [

11] to conceptualize sustainability transformation as a complex adaptive system where capabilities and mechanisms interact dynamically rather than linearly. As Wang and Zhang [

12] demonstrate in their work on digital transformation, viewing organizational elements as an integrated system where components interact synergistically produces more robust outcomes than addressing elements in isolation. Following this perspective, we conceptualize our four integration mechanisms (governance, strategic, operational, and performance) as interconnected subsystems within a larger organizational system, where changes in one subsystem necessarily affect others through feedback loops, emergent properties, and non-linear interactions. This systems view helps explain why piecemeal sustainability initiatives often fail to produce substantive transformation, while integrated approaches that consider whole-system dynamics tend to generate more significant outcomes.

Within this system’s framework, organizational capabilities for paradox navigation, power mobilization, and learning function as dynamic capacities that enable the system to adapt and evolve in response to both internal tensions and external pressures. The effectiveness of these capabilities is moderated by contextual factors, including regulatory environments and inter-organizational relationships, which function as broader system parameters that constrain or enable transformation possibilities. This systems perspective provides a coherent theoretical lens for understanding how various organizational elements interact to produce sustainability transformations that are greater than the sum of individual initiatives.

The study addresses three critical research questions:

What organizational capabilities enable effective navigation of sustainability paradoxes and tensions?

How do organizations successfully integrate sustainability throughout their systems rather than compartmentalizing it?

How do power dynamics and contextual factors influence the effectiveness of sustainability transformation approaches?

By examining these questions through a mixed-methods approach, this research contributes to sustainability science in three distinct ways. First, while paradox theory has been applied to sustainability contexts [

13,

14], there remains a limited understanding of the specific organizational capabilities and integration mechanisms that enable effective navigation of sustainability paradoxes across different contexts. Our study addresses this gap by identifying and empirically validating the capabilities and mechanisms that facilitate the translation of paradoxical thinking into substantive sustainability transformations.

Second, previous research has identified the importance of integrating sustainability into business models [

15,

16] but has paid less attention to the specific integration mechanisms and their relative effectiveness across diverse organizational contexts. This research identifies four distinct integration mechanisms and demonstrates how they interact and evolve over time to create substantive transformation.

Third, while the importance of power in sustainability transformation has been acknowledged [

17,

18], existing research often treats power as a contextual variable rather than a central dynamic in transformation processes. This study directly examines how power relationships shape transformation processes and how change agents navigate and reshape power dynamics to advance sustainability.

The research aligns with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

19], particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), by identifying organizational practices that enable more sustainable production systems and effective sustainability governance. Through its empirically grounded examination of sustainability transformation processes across diverse organizational contexts, this research bridges micro-organizational and macro-institutional perspectives on sustainability challenges.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Philosophy and Approach

This study adopts a critical realist perspective [

49], which recognizes that while organizational reality exists independently of our knowledge of it, understanding is always mediated by social constructions and power relationships. This perspective allows examination of both objective institutional conditions and subjective interpretations of these conditions by organizational actors, while maintaining awareness of the underlying power dynamics that shape these interpretations.

Critical realism is particularly appropriate for sustainability research because it accommodates both the biophysical realities of environmental challenges and the socially constructed nature of sustainability concepts and practices [

50]. It enables investigation of causal mechanisms while recognizing that these mechanisms operate within complex open systems where multiple factors interact.

The mixed-methods design reflects this philosophy by combining quantitative measurement of key relationships with qualitative exploration of the mechanisms and meanings that underlie these relationships. This approach enables both theory testing and theory building, recognizing that sustainability transformations involve both measurable outcomes and socially constructed processes.

3.2. Research Design

This study employed a sequential mixed-methods design [

51] with three primary components:

Quantitative survey (n = 234) of sustainability professionals across multiple sectors.

Semi-structured interviews (n = 42) with organizational change agents and leaders.

Comparative case studies (n = 6) of organizations demonstrating different transformation patterns.

This design allowed for testing relationships between key variables quantitatively while developing a deeper understanding of mechanisms and contexts through qualitative inquiry. The sequential approach enabled insights from each phase to inform subsequent data collection and analysis, enhancing integration between methods.

Following Teddlie and Tashakkori’s [

52] taxonomy of mixed methods designs, our approach represents an explanatory sequential design where quantitative results informed qualitative inquiry, with an embedded component where qualitative data collection occurred within the case study phase to deepen understanding of organizational contexts.

3.3. Sampling and Participants

Survey participants were recruited through professional sustainability networks and stratified to ensure representation across sectors (manufacturing, services, public sector, and non-profit), organizational sizes, and geographical regions. To address potential self-selection bias, we employed a two-stage stratified sampling approach. First, we stratified our sample by industry sector, organization size, and geographic region to ensure broad representation. Second, we specifically targeted organizations at different stages of sustainability engagement through multiple recruitment channels, including sustainability networks, industry associations, and direct outreach to organizations with limited public sustainability commitment.

To mitigate self-reporting bias, we triangulated survey responses with objective indicators where available, including publicly reported sustainability metrics and third-party assessments.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

This demographic profile illustrates the diverse organizational contexts represented in our sample. The relatively balanced distribution across sectors (manufacturing, services, public sector, and non-profit) enables cross-sectoral comparisons, while the range of organization sizes allows examination of how scale influences sustainability approaches. The geographic distribution, with representation across major regions, facilitates analysis of contextual variations in sustainability transformation. The respondent roles indicate that most participants (89%) hold positions with substantial involvement in organizational decision-making, enhancing the credibility of their assessments of organizational practices and outcomes. The sustainability performance self-assessment reveals that while organizations at advanced stages are well-represented (63% in “Leading” or “Advancing” categories), the sample also includes organizations at earlier transformation stages (37% in “Beginning” or “Lagging” categories), enabling analysis of capability development across different transformation phases.

Interview participants were selected using purposive sampling to capture diverse perspectives on sustainability transformation. Selection criteria included organizational role, transformation experience, and sector representation. To ensure representation of critical perspectives, we deliberately included participants from organizations at different stages of sustainability transformation, including those experiencing significant challenges. The interview sample included sustainability professionals (n = 18), senior executives (n = 12), middle managers (n = 8), and external stakeholders (n = 4).

Case study organizations were selected using theoretical sampling [

53] to represent maximum variation across key dimensions: transformation approach (incremental vs. radical), institutional context (supportive vs. challenging), organizational type (incumbent vs. entrepreneurial), and sector (manufacturing, services, public, or hybrid). This sampling approach allowed for cross-case comparison of how different organizational contexts influence sustainability transformation processes.

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the six case organizations.

This case selection represents theoretical sampling designed to capture maximum variation across key dimensions of sustainability transformation. The organizations span different sectors (consumer goods, manufacturing, financial services, healthcare, social enterprise, and public–private partnership), sizes (small to large), and geographic scopes (regional to global). Their transformation approaches vary substantially, from Alpha’s strategic integration to Epsilon’s purpose-driven approach, enabling comparative analysis of different transformation pathways. The institutional contexts range from supportive to challenging, allowing examination of how external conditions enable or constrain transformation efforts. Performance trajectories also vary, with some organizations demonstrating accelerating progress (Alpha, Gamma, Epsilon), others showing steady improvement (Delta), and some experiencing plateaus (Beta) or variable progress (Zeta). This variation enables analysis of both successful transformation patterns and implementation challenges across diverse organizational contexts.

We recognize the potential limitation of over-representing sustainability-committed organizations. To address this, we purposefully included organizations at different stages of sustainability engagement by (1) stratifying our sample based on preliminary sustainability commitment assessments from industry reports and public disclosures; (2) partnering with industry associations whose memberships include organizations with varying sustainability orientations; and (3) employing snowball sampling to reach organizations not publicly identified with sustainability initiatives. Despite these efforts, organizations in early transformation stages (37% of our sample) remain somewhat underrepresented compared with those in advancing (41%) or leading (22%) stages.

3.4. Data Collection

Survey Instrument: The survey instrument included validated scales measuring key constructs, including paradox navigation capabilities, integration practices, power mobilization strategies, organizational learning mechanisms, and sustainability transformation outcomes. Each construct was measured using multiple items on 7-point Likert scales, adapted from existing measures where available and developed through a rigorous process of expert review and pilot testing where needed.

Our operationalization of paradox navigation capabilities draws on validated scales from Smith et al. [

54] and Knight & Paroutis [

55], adapted to the sustainability context. Integration mechanisms were measured using items developed from Gond et al. [

56] and refined through expert validation and pilot testing. Both constructs underwent rigorous content validity assessment with five academic experts and three sustainability practitioners to ensure they comprehensively captured the theoretical dimensions.

The instrument was pilot-tested with 15 sustainability professionals and refined based on their feedback. Cronbach’s alpha for all scales exceeded 0.80, indicating good internal consistency.

Table 3 provides sample items for each key construct. The complete survey instrument is included in

Appendix A.

These sample items illustrate how the key theoretical constructs were operationalized in the survey instrument. The paradox navigation items assess capabilities for recognizing and working productively with tensions, from basic acknowledgment of competing demands to more sophisticated practices for generating creative solutions. Integration items measure the extent to which sustainability is embedded at different organizational levels, from governance oversight to strategic priorities, operational processes, and performance management. Power mobilization items assess the political capabilities deployed to advance sustainability, including alliance building, strategic framing, and opportunity exploitation. Learning items measure mechanisms for developing sustainability capabilities, from team reflection to formal review processes and external knowledge networks. Transformation outcome items assess both the depth of change (from incremental improvement to fundamental transformation) and breadth across environmental, social, and economic dimensions. Collectively, these items enable quantitative assessment of the key constructs in our theoretical framework while maintaining a connection to their qualitative manifestations in organizational practice.

To address potential common method bias, we implemented procedural remedies following Podsakoff et al. [

57], including psychological separation of predictor and criterion variables, assurance of anonymity, and varied response formats. We also conducted Harman’s single-factor test and common latent factor analysis to assess and control for common method variance.

Interviews: Semi-structured interviews lasting 60–90 min explored participants’ experiences with sustainability transformation initiatives. The interview protocol addressed institutional enablers and barriers, strategies for navigating power dynamics, approaches to managing sustainability tensions, learning processes, and integration practices. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded for analysis.

To enhance trustworthiness, we employed member checking (sending interview summaries to participants for verification) and maintained reflexive memos documenting how the researcher positionality might influence data collection and interpretation. The complete interview protocol is included in

Appendix B.

Case Studies: For each case organization, multiple data sources were collected using a systematic protocol:

Interviews with diverse organizational members (6–8 per organization).

Internal documentation on sustainability initiatives.

Public sustainability reports and communications (5 years of historical data).

Observational data from site visits and meetings (10–15 h per organization).

Archival data on organizational history and context.

This multi-source approach enabled triangulation of findings and reduced reliance on retrospective accounts. For each case, we developed a detailed chronology of sustainability initiatives, including both successful and unsuccessful efforts, to understand transformation processes over time.

To strengthen the validity of our transformation outcome measures beyond self-reported assessments, we collected objective indicators where available for a subset of our sample (n = 86). These indicators included the following:

Environmental performance metrics: Percentage reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (past three years), waste diversion rates, energy efficiency improvements, and water usage reduction.

Innovation indicators: Number of sustainability innovations launched, percentage of products/services redesigned with sustainability criteria, and R&D investment in sustainability solutions.

Governance indicators: Presence of board-level sustainability committee, proportion of executive compensation tied to sustainability metrics, and quality of sustainability disclosure.

External validation: Third-party sustainability ratings (e.g., CDP scores, DJSI inclusion), industry sustainability awards, and NGO recognition.

We developed a composite objective indicator index by standardizing and averaging these metrics. The correlation between our self-reported transformation outcome measure and this objective indicator index was strong (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), providing additional confidence in our primary outcome measure. Moreover, when we conducted regression analyses using only the objective indicator as the dependent variable, we found consistent patterns of relationships with our key predictors: integration practices (β = 0.39, p < 0.01), paradox navigation capabilities (β = 0.28, p < 0.01), and power mobilization (β = 0.25, p < 0.01). For transparency, we conducted sensitivity analyses using only the subsample with objective indicators, finding consistent results for our main hypothesized relationships, albeit with reduced statistical power.

3.5. Data Analysis

The measurement model results demonstrate strong psychometric properties for all key constructs. Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.86 to 0.93 indicate excellent internal consistency reliability, substantially exceeding the conventional threshold of 0.70. Similarly, composite reliability values (0.88 to 0.95) demonstrate strong construct reliability. Average variance extracted (AVE) values (0.65 to 0.74) exceed the recommended threshold of 0.50, indicating good convergent validity—the items for each construct correlate well with each other and represent the same underlying concept. All constructs demonstrate discriminant validity based on both the Fornell–Larcker criterion (the square root of AVE for each construct exceeds its correlation with other constructs) and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio (all ratios below 0.85). These results provide confidence that the measurement model appropriately distinguishes between the theoretical constructs and captures their intended meaning, establishing a solid foundation for the structural model analysis that examines relationships between these constructs.

Quantitative Analysis: Survey data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) to test relationships between constructs in the theoretical framework. Before hypothesis testing, measurement validation was conducted through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the convergent and discriminant validity of constructs.

Table 4 presents key measurement model statistics.

The structural model was specified based on the theoretical framework, with direct paths from all independent variables to transformation outcomes and interaction terms to test moderating relationships. Multigroup analysis compared path coefficients across sectors and organizational types to test for contextual differences.

Qualitative Analysis: Interview and case study data were analyzed using thematic analysis [

58] with the following steps:

Initial coding using a preliminary coding scheme derived from the theoretical framework.

Coding refinement through comparison and discussion among three researchers.

Theme development: organizing codes into potential themes and subthemes.

Theme review in relation to coded extracts and the entire dataset.

Theme definition with clear naming and identification of representative quotes.

Cross-case analysis to identify patterns, similarities, and differences.

Following Braun and Clarke’s [

58] thematic analysis approach, we employed a hybrid coding strategy combining deductive and inductive approaches. Initial coding was guided by our theoretical framework, with codes derived from paradox theory, organizational learning, and power dynamics literature. As analysis progressed, we remained open to emergent themes not captured by our initial coding framework. To enhance interpretive rigor, three researchers independently coded a subset of interviews, compared interpretations, and resolved discrepancies through discussion. This iterative process continued until theoretical saturation was reached. We triangulated qualitative findings with quantitative results through joint displays and integrated analysis sessions where the research team systematically compared patterns across data sources.

The coding process combined deductive and inductive approaches, with initial codes derived from theory but allowing for emergent codes from the data.

Table 5 provides an overview of the final coding framework with example codes.

Integration: Quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated through a connecting approach [

59], with qualitative data explaining mechanisms underlying quantitative relationships and illuminating contextual contingencies. This integration enhanced the validity of findings through methodological triangulation while enabling a more nuanced understanding of complex causal mechanisms.

To systematize integration, we developed joint display matrices that explicitly linked quantitative relationships with qualitative explanations. We also conducted integrated analysis sessions where researchers collaboratively interpreted quantitative and qualitative results, identifying convergence, complementarity, and discordance between findings from different methods.

This coding framework illustrates how we systematically analyzed the qualitative data to develop a nuanced understanding of sustainability transformation processes. The framework combines deductive codes derived from our theoretical foundation (e.g., paradox navigation, integration mechanisms, power dynamics) with inductive codes that emerged from the data (e.g., specific types of resistance patterns, contextual variations). The hierarchical structure—organizing codes into themes and subthemes—enabled us to identify patterns at different levels of abstraction, from specific practices to broader capability categories. The example codes demonstrate how abstract theoretical concepts were grounded in concrete organizational practices and experiences. For instance, “paradox navigation” was operationalized through specific indicators such as “tension recognition” and “rejection of false dichotomies.” This coding approach facilitated systematic cross-case comparison while remaining sensitive to context-specific nuances, enabling us to identify both common patterns and important variations in how organizations navigate sustainability transformations across different contexts.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results: Relationships Between Key Constructs

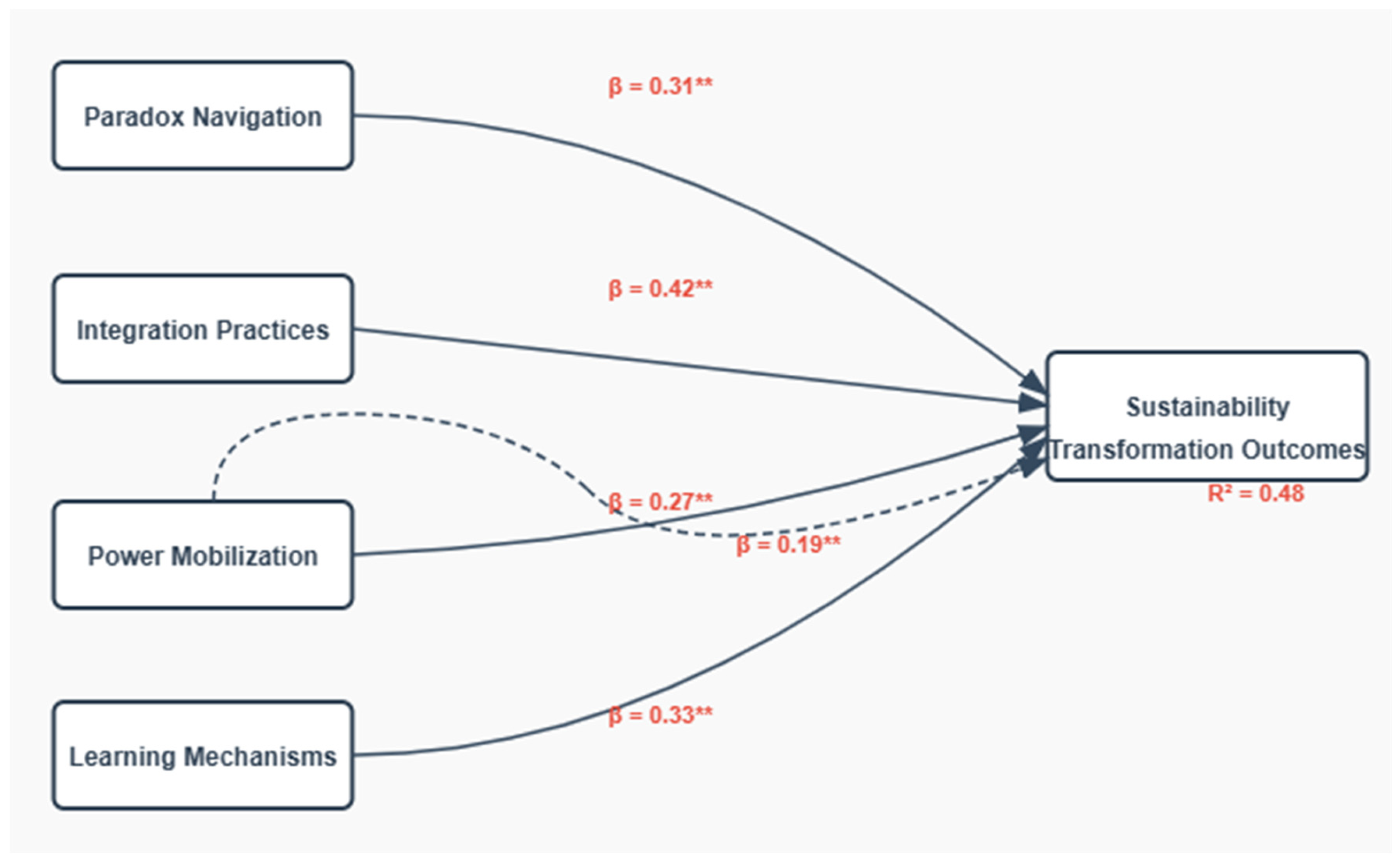

Structural equation modeling revealed significant relationships between key constructs in the theoretical framework (see

Table 6 and

Figure 1).

The model demonstrated good fit (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.062) and explained 48% of the variance in sustainability transformation outcomes. Notably, integration practices emerged as the strongest predictor of transformation outcomes (β = 0.42, p < 0.01, f2 = 0.25), followed by learning mechanisms (β = 0.33, p < 0.01, f2 = 0.16) and paradox navigation capabilities (β = 0.31, p < 0.01, f2 = 0.15). The effect sizes indicate that integration practices have a medium to large practical significance, while most other predictors have medium effects.

The significant interaction between power mobilization and integration practices (β = 0.19, p < 0.01, f2 = 0.08) reveals how power dynamics fundamentally shape the effectiveness of integration efforts. This finding extends beyond statistical significance to illuminate a critical theoretical insight: integration mechanisms alone are insufficient for transformation unless accompanied by the mobilization of supportive power resources. For example, in our case organizations, sustainability managers who successfully framed integration initiatives in terms of strategic business benefits (power mobilization through strategic framing) significantly enhanced the effectiveness of governance integration mechanisms by securing executive commitment and resource allocation. Theoretically, this interaction effect suggests that power operates as both an enabler and a multiplier of integration effects rather than merely as a parallel influence, challenging conventional models that treat power as a separate variable rather than an interactive force.

Figure 2 illustrates this interaction effect, showing how the relationship between integration practices and transformation outcomes varies at different levels of power mobilization.

Multigroup analysis revealed significant contextual differences in these relationships:

Sectoral differences: The relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes was stronger in manufacturing (β = 0.38, p < 0.01) than services (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that manufacturing organizations face more complex sustainability tensions requiring sophisticated navigation capabilities. Conversely, power mobilization had stronger effects in service organizations (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) than in manufacturing (β = 0.22, p < 0.05), reflecting the more relationship-based nature of service contexts.

Size differences: Paradox navigation capabilities had stronger effects in larger organizations (β = 0.37, p < 0.01) than smaller ones (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that managing competing demands becomes more critical as organizational complexity increases. In contrast, integration practices showed more consistent effects across organizational sizes, indicating their fundamental importance regardless of scale.

Geographic differences: The effect of power mobilization on transformation outcomes was stronger in Asian organizations (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) than in North American (β = 0.22, p < 0.05) or European organizations (β = 0.25, p < 0.05), indicating important cultural variations in how power influences transformation processes. Learning mechanisms showed the most consistent effects across geographic contexts (β ranging from 0.30 to 0.36), suggesting the universal importance of learning capabilities.

Performance level differences: The relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes was stronger for organizations at earlier stages of sustainability transformation (β = 0.39, p < 0.01) than for sustainability leaders (β = 0.26, p < 0.05). Conversely, integration practices had stronger effects for advanced organizations (β = 0.45, p < 0.01) than beginners (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), suggesting that different capabilities may be critical at different stages of transformation.

These contextual variations challenge universal prescriptions for sustainability transformation, highlighting instead the importance of tailoring approaches to specific organizational contexts and transformation stages.

4.2. Qualitative Findings: Mechanisms and Contextual Dynamics

Thematic analysis of interview and case study data revealed four key themes that illuminate the mechanisms underlying the quantitative results.

Table 7 presents a joint display integrating quantitative relationships with qualitative explanations.

This joint display reveals how qualitative findings explain and contextualize the quantitative relationships, providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms driving sustainability transformation.

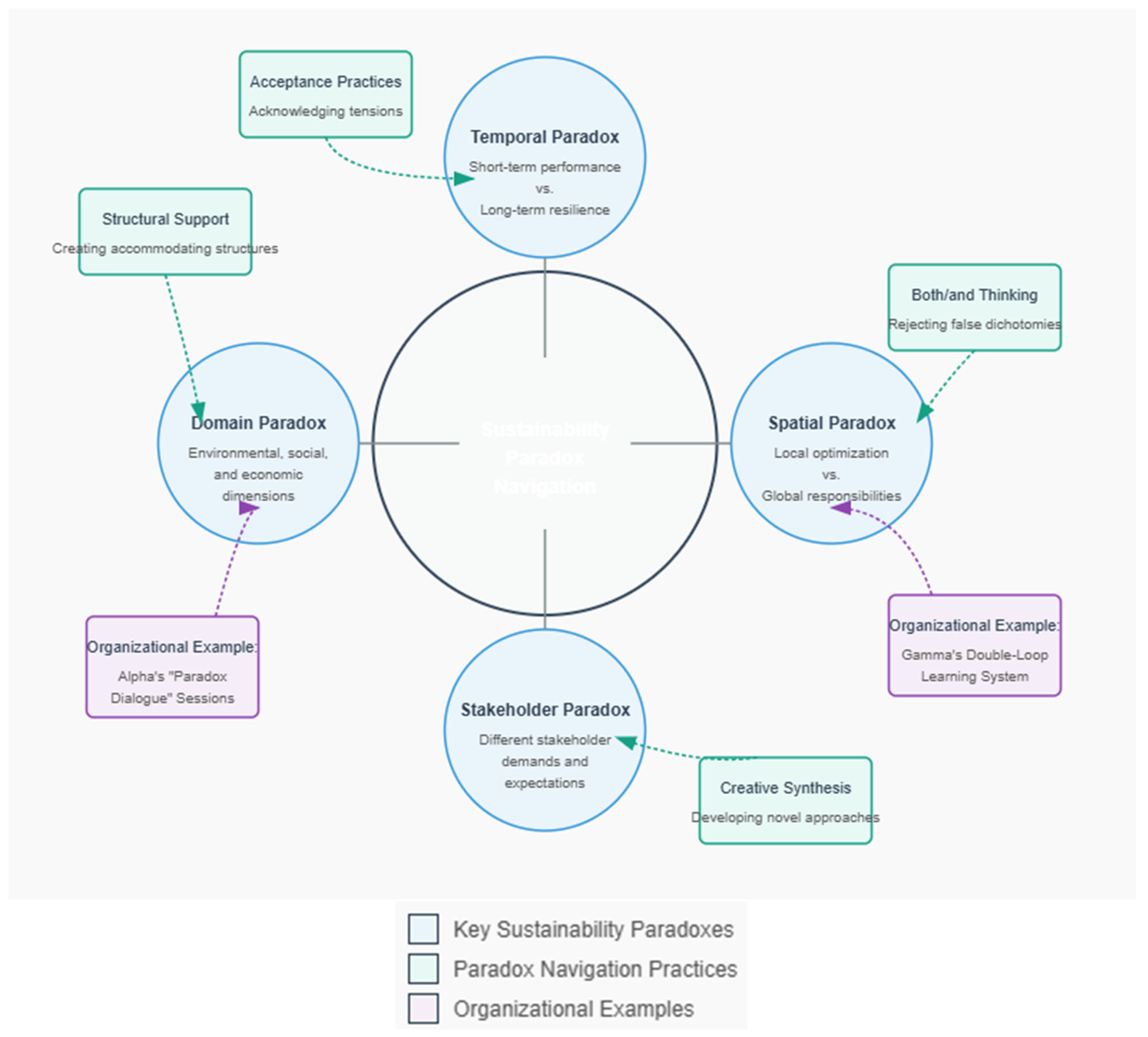

4.2.1. Paradox Navigation in Practice

Organizations achieving substantive sustainability transformations developed structured approaches to paradox navigation rather than avoiding or eliminating tensions. Our findings revealed that paradox navigation involves both cognitive capabilities (recognizing and reframing tensions) and practical mechanisms (processes and structures that enable constructive engagement with tensions).

The most effective paradox navigation approaches included the following:

Acceptance practices: Acknowledging tensions without attempting to resolve them.

Both/and thinking: Rejecting false dichotomies between competing objectives.

Creative synthesis: Developing novel approaches that address multiple objectives simultaneously.

Structural support: Creating organizational structures that accommodate complexity.

Case study data revealed significant differences in paradox navigation capabilities across organizations. Alpha (Consumer Goods) institutionalized paradox navigation through formal processes:

“Alpha created dedicated ‘paradox dialogue’ sessions where cross-functional teams explicitly discussed tensions between competing sustainability objectives. These structured conversations transformed how the organization approached sustainability decisions, moving from either/or thinking to both/and innovation.”

(Case Study Analysis)

The effectiveness of paradox navigation approaches varied based on the institutional logics dominant within different organizational contexts. Organizations operating primarily within market logic typically faced greater challenges in developing paradox navigation capabilities, as the either/or thinking characteristic of market institutions (efficiency, competition, profit maximization) often conflicted with the both/and approaches needed for sustainability. As one manager explained,

“In our industry, the market logic is so dominant that it’s incredibly difficult to get people to think beyond financial metrics. We’ve had to deliberately create spaces where ecological and community logics are given equal weight to financial considerations in decision processes. Without these structured approaches, market thinking automatically dominates.”

(Participant 27, Financial Services)

Organizations that successfully developed paradox navigation capabilities often created what we term “logic translation mechanisms”—processes that helped organizational members recognize the value of sustainability initiatives within their dominant institutional logic while gradually expanding their capacity to work across logics. Delta (Healthcare) provides an illustrative example:

“In healthcare, the professional logic of patient care is dominant. We’ve found that framing sustainability tensions in terms of long-term patient wellbeing helps clinicians engage with environmental considerations that might otherwise be dismissed as secondary. Over time, this has expanded their capacity to work with both professional and ecological logics simultaneously.”

(Delta, Sustainability Director)

In contrast, Beta (Manufacturing) consistently framed sustainability decisions as either/or choices, leading to oscillation between priorities rather than integrated solutions:

“Beta’s approach was characterized by alternating priorities between financial and sustainability objectives. When business conditions were favorable, sustainability initiatives advanced; when pressures increased, they were quickly sacrificed. This oscillation prevented the development of integrated approaches that could advance both objectives simultaneously.”

(Case Study Analysis)

The qualitative data also revealed that effective paradox navigation is not merely cognitive but requires emotional capabilities:

“The hardest part isn’t intellectual—it’s emotional. People get uncomfortable with ambiguity and contradictions. We’ve had to develop emotional capacity to sit with that discomfort rather than rushing to eliminate tensions through premature either/or decisions.”

(Participant 37, Non-profit)

This emotional dimension helps explain why paradox navigation capabilities develop unevenly across organizations and why structural supports are necessary to sustain paradoxical thinking in the face of discomfort and uncertainty.

However, paradox navigation also showed limitations in addressing systemic sustainability challenges. While it enabled more creative approaches to organizational tensions, some participants noted that certain sustainability challenges require more radical system change rather than paradoxical accommodation:

“There are times when we need to recognize that some business models are fundamentally unsustainable and require transformation rather than optimization. Paradoxical thinking helps us navigate transitions, but shouldn’t prevent us from acknowledging when deeper change is needed.”

(Participant 8, Sustainability Consultant)

This critique highlights the importance of complementing paradox navigation with critical reflection on system boundaries and transformation horizons (see

Figure 3).

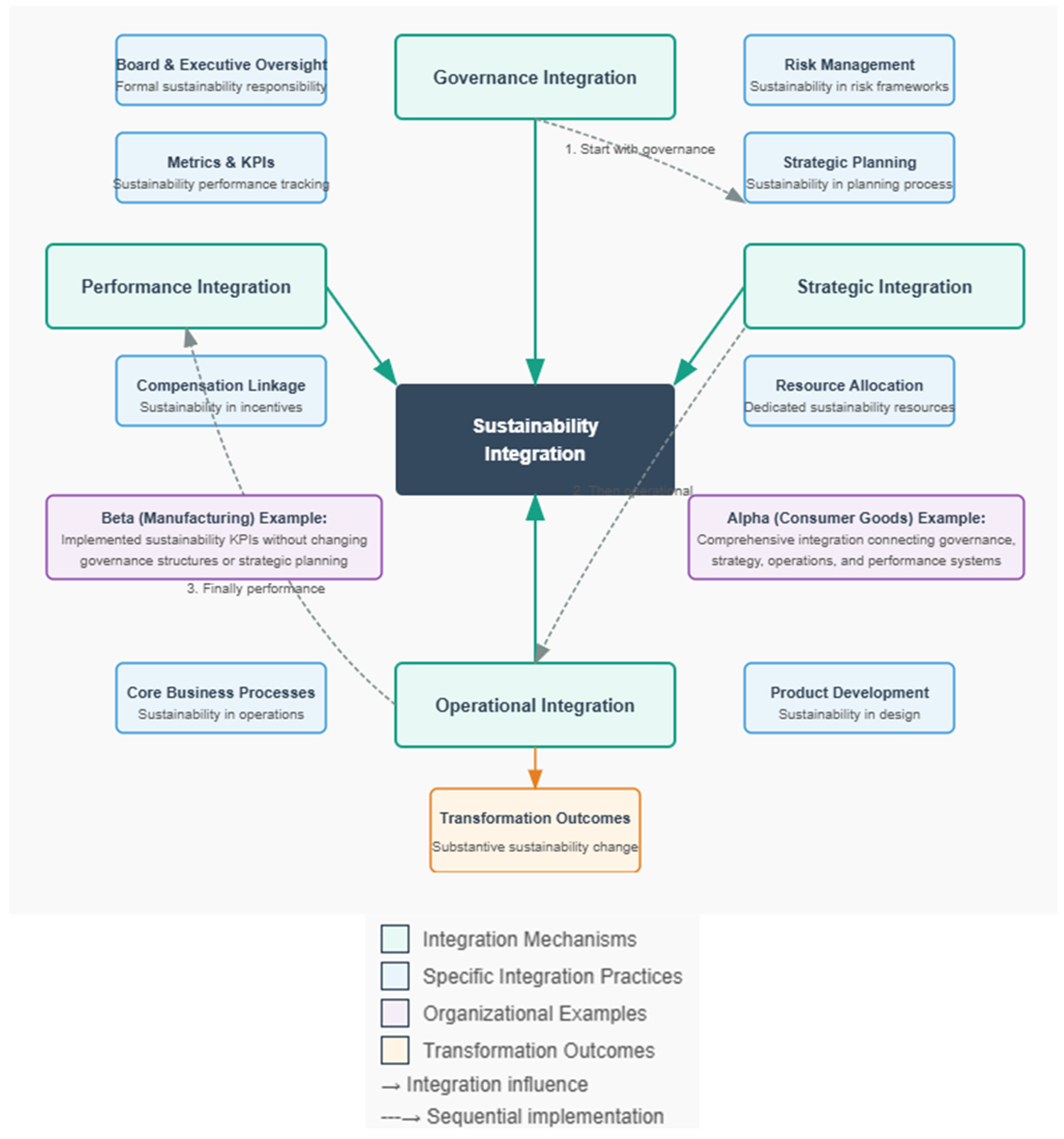

4.2.2. Integration Mechanisms and Their Effectiveness

The qualitative data explained why integration practices emerged as the strongest predictor of transformation outcomes in the quantitative analysis. Organizations achieving substantial transformation have embedded sustainability considerations into core business processes rather than treating sustainability as a specialized function (see

Figure 4).

Effective integration mechanisms included the following:

Governance integration: Sustainability oversight at board and executive levels.

Strategic integration: Sustainability embedded in strategic planning and goal-setting.

Operational integration: Sustainability incorporated into core business processes.

Performance integration: Sustainability metrics linked to compensation and advancement.

Case study data revealed that these integration mechanisms were most effective when implemented as coordinated systems rather than isolated practices. This was particularly evident in the contrast between Alpha and Beta:

“Alpha implemented a comprehensive integration approach that connected governance, strategy, operations, and performance systems. Sustainability considerations flowed coherently from board-level discussions through strategic planning and into operational decisions. In contrast, Beta implemented sustainability KPIs without changing governance structures or strategic planning processes, resulting in disconnected initiatives that struggled to gain traction.”

(Case Study Analysis)

The temporal sequence of integration also emerged as important. Gamma (Financial Services) found that beginning with strategic integration created a foundation for subsequent operational changes:

“We started by integrating sustainability into our strategic planning process. This created the mandate for operational changes, which then required performance metrics to drive accountability. Trying to implement performance metrics without the strategic foundation didn’t work.”

(Gamma, Executive)

This finding aligns with the quantitative result showing stronger effects of integration in more advanced organizations, suggesting that integration creates compound benefits as it matures and expands throughout organizational systems.

Our analysis also revealed different integration pathways across organizational types. While large incumbents typically pursued formal integration through established management systems, entrepreneurial organizations often built integrated approaches from inception:

“As a purpose-driven startup, we didn’t need to integrate sustainability into our existing systems—we designed our systems around sustainability from the beginning. Our challenge wasn’t integration but maintaining this integrated approach as we scaled.”

(Epsilon, Founder)

These different pathways highlight the importance of tailoring integration approaches to organizational context rather than applying universal best practices.

Integration also faced significant implementation challenges, particularly in organizations with complex legacy systems or significant internal resistance:

“The hardest part of integration wasn’t the technical aspects but overcoming entrenched interests and established routines. We had to recognize that integration isn’t just a structural challenge but a political and cultural one.”

(Delta, Sustainability Director)

This observation connects integration practices to power dynamics, explaining the significant interaction effect found in the quantitative analysis.

4.2.3. Power Dynamics in Transformation Processes

Change agents consistently identified power dynamics as critical to transformation outcomes. Our analysis revealed that power operates through multiple dimensions in sustainability contexts, including formal authority, resource control, expertise, and discursive influence. Successful change agents developed sophisticated capabilities for navigating these different power dimensions.

As one sustainability director explained,

“Understanding the power landscape is essential. I’ve learned to map who has decision-making authority, who influences those decision-makers, and who might resist change. This mapping helps me develop targeted strategies for different stakeholders.”

(Participant 7, Manufacturing)

Successful change agents employed various strategies to navigate power dynamics:

Strategic framing: Articulating sustainability in terms that resonated with powerful stakeholders’ priorities.

Coalition building: Creating networks of support across organizational boundaries.

Resource mobilization: Securing financial, human, and symbolic resources.

Timing exploitation: Identifying and leveraging windows of opportunity.

These strategies were particularly important in organizations where sustainability values were not deeply institutionalized:

“In our organization, sustainability isn’t yet part of the core business model. I have to be strategic about when and how I introduce sustainability considerations. I’ve found that connecting them to cost savings, risk reduction, or customer expectations gets much more traction than environmental arguments alone.”

(Participant 23, Financial Services)

The qualitative data also revealed that power dynamics were not static but evolved throughout transformation processes. As initiatives demonstrated value, sustainability advocates often gained additional influence:

“Five years ago, we were begging for a seat at the table. Now business units come to us proactively because they’ve seen how sustainability initiatives create value. Success has given us credibility and influence we didn’t have before.”

(Participant 15, Manufacturing)

This temporal evolution helps explain the quantitative finding that power mobilization has different effects across organizational contexts. In some contexts, power mobilization is critical for initiating transformation; in others, it becomes more important for maintaining momentum and overcoming resistance.

Our analysis also revealed significant power asymmetries that constrained transformation, particularly regarding global supply chains and relationships with marginalized stakeholders:

“We’ve made progress internally, but our most significant sustainability impacts are in our supply chain where our influence is limited. Building power to affect these broader systems remains our biggest challenge.”

(Participant 29, Retail)

These persistent power asymmetries highlight limitations in current sustainability approaches and point to the need for more systemic transformation strategies that address fundamental power structures.

Additionally, digital technologies emerged as increasingly important tools for power mobilization across our case organizations. As one sustainability director explained,

“Digital platforms have fundamentally changed how we mobilize support for sustainability initiatives. Our sustainability dashboard creates transparency around environmental metrics that previously weren’t visible to most employees. This visibility has democratized access to information and enabled more people to participate meaningfully in sustainability conversations, creating a broader power base for change.”

(Participant 14, Technology)

The strategic use of digital tools varied across organizational contexts. In knowledge-intensive organizations, digital collaboration platforms facilitated coalition building across traditional boundaries:

“Our company-wide digital collaboration platform allows sustainability champions to connect across geographical and departmental boundaries. This has been transformative for building coalitions—people who would never have connected in the traditional hierarchy now share ideas and coordinate actions. It’s created a distributed network of change agents that’s much harder to dismiss than isolated sustainability advocates.”

(Gamma, Innovation Lead)

In manufacturing contexts, digital tools were more often used to make the business case through data visualization:

“Our predictive analytics system has become a powerful tool for influence. When we can show in real-time how sustainability investments affect operational efficiency, quality metrics, and risk exposure, we shift from making values-based arguments to evidence-based ones. This has completely changed conversations with operations and finance leaders.”

(Beta, Sustainability Manager)

These examples illustrate how digital technologies can reshape power dynamics by democratizing information access, enabling new coalition formations, and strengthening evidence-based influence strategies.

4.2.4. Learning Systems for Sustainability

Organizations with strong transformation outcomes implemented systematic approaches to learning that connected individual, group, and organizational levels. Our analysis revealed that effective learning for sustainability differs from conventional organizational learning in its integration of diverse knowledge types, explicit attention to power dynamics, and focus on system transformation.

“We’ve developed a multi-level learning system for sustainability. Individual employees participate in sustainability training and have personal development goals. Teams have regular reflection sessions to discuss what’s working and what isn’t. At the organizational level, we have quarterly reviews where we assess overall progress and adjust our approach.”

(Participant 31, Healthcare)

Effective learning systems included the following:

Psychological safety: Creating environments where people feel safe discussing failures.

Feedback mechanisms: Developing robust approaches to monitoring and assessment.

Reflection practices: Institutionalizing regular reflection on experience.

Knowledge management: Creating systems to capture and share learning.

Delta (Healthcare) demonstrated a particularly robust learning system:

“Delta implemented a formal ‘sustainability learning cycle’ with quarterly review and reflection processes. Each review examined outcomes against goals, identified barriers to progress, and generated insights for improvement. These insights were documented in a knowledge management system accessible to all employees and incorporated into future planning.”

(Case Study Analysis)

The case studies revealed that double-loop learning—questioning fundamental assumptions—was particularly important for transformative change. Gamma (Financial Services) demonstrated this approach:

“When our initial sustainability efforts produced limited results, we didn’t just adjust our methods—we questioned our underlying assumptions about the relationship between sustainability and our business model. This deeper reflection led to fundamental changes in how we defined our purpose and strategy, enabling much more significant transformation.”

(Gamma, Executive)

This finding helps explain the strong quantitative relationship between learning mechanisms and transformation outcomes. Organizations that developed robust learning systems were able to continuously adapt their approaches based on experience, accelerating transformation over time.

However, our analysis also revealed significant barriers to effective learning, including time pressures, defensive routines, and power dynamics that constrained open dialogue:

“The biggest barrier to learning isn’t lack of information but lack of time and space for reflection. When everyone is focused on delivering results, stepping back to question assumptions becomes a luxury few can afford.”

(Participant 4, Consulting)

These barriers were particularly evident in organizations facing significant market pressures or operating in turbulent environments, highlighting the tension between short-term performance demands and the reflective practices necessary for transformative learning.

Additionally, digital knowledge management systems played a crucial role in accelerating learning across all transformation stages. Organizations with more sophisticated digital learning infrastructures demonstrated faster capability development and more consistent implementation. At Gamma, the implementation of an AI-enhanced knowledge management system transformed how sustainability learning was captured and disseminated:

“Our digital knowledge platform doesn’t just store information—it actively connects people with relevant sustainability insights based on their roles and current challenges. When someone enters a new sustainability-related project, the system automatically suggests relevant case studies, expert contacts, and lessons learned from similar initiatives. This dramatically accelerates learning cycles and prevents repeated mistakes.”

(Gamma, Knowledge Manager)

The most effective digital learning systems integrated four key elements: (1) accessible repositories of sustainability knowledge; (2) collaboration tools that connected practitioners across boundaries; (3) analytics capabilities that identified patterns and insights; and (4) personalization features that delivered relevant knowledge to users based on their context and needs. Organizations with all four elements demonstrated significantly faster capability development than those with more fragmented approaches.

4.3. Contextual Contingencies of Transformation

The qualitative data revealed significant contextual contingencies that explained variation in quantitative relationships across organizational types and sectors. These contingencies highlight how sustainability transformation approaches must be tailored to specific contexts rather than following universal prescriptions.

The qualitative data revealed how these contextual factors shaped transformation approaches. Ownership structure significantly influenced transformation pathways, with publicly traded companies facing distinct challenges:

“As a public company, quarterly earnings pressure creates a constant tension with longer-term sustainability investments. We’ve had to develop specific approaches to manage this tension, including dedicated innovation funds that protect longer-term initiatives from short-term pressures.”

(Alpha, Executive)

In contrast, Epsilon’s social enterprise structure created different dynamics:

“Our legal structure as a benefit corporation fundamentally shapes our approach to sustainability. It’s built into our governance, with directors legally required to consider social and environmental impacts alongside financial returns. This creates institutional support for sustainability that most conventional companies lack.”

(Epsilon, Director)

Sectoral dynamics created distinct transformation pathways. Manufacturing organizations typically emphasized operational efficiency and product innovation:

“In manufacturing, our sustainability transformation focused heavily on resource efficiency, circular material flows, and product redesign. These tangible aspects provided clear business cases that helped overcome resistance.”

(Beta, Manager)

Service organizations, by contrast, focused more on human capital and digital transformation:

“As a service business, our biggest sustainability impacts relate to our people and our digital infrastructure. Our transformation emphasized employee well-being, inclusive culture, and digital technologies that reduce environmental impact while enhancing service quality.”

(Gamma, Director)

The stronger effect of paradox navigation in manufacturing (β = 0.38) compared with services (β = 0.24) warrants deeper explanation beyond simply citing ‘complex material trade-offs.’ Our further analysis suggests three factors that better account for this difference. First, the visibility and measurability of tensions in manufacturing contexts make paradoxes more concrete and therefore more amenable to deliberate navigation strategies. In service organizations, sustainability tensions often manifest in more diffuse and less tangible ways, making them harder to identify and address systematically.

Figure 5 below provides an overview of the contextual contingencies of sustainability transformation.

Large incumbents benefit most from learning systems but struggle with integration practices.

Entrepreneurial organizations excel at integration but face challenges with power mobilization.

B2C sectors show high effectiveness with power mobilization strategies, leveraging consumer pressure.

Global organizations require strong learning systems and power mobilization to manage complexity.

Paradox navigation is most effective in public sector contexts where multiple stakeholder demands are common.

Second, manufacturing organizations typically have more established process improvement methodologies (e.g., lean manufacturing, Six Sigma) that provide structured frameworks for paradox navigation once sustainability tensions are recognized. Our interviews with manufacturing leaders revealed how they adapted existing problem-solving approaches to address sustainability paradoxes, whereas service organization leaders often lacked comparable methodological foundations.

Third, the regulated nature of many manufacturing processes means that sustainability tensions frequently emerge as explicit compliance versus innovation trade-offs, creating clear opportunities to apply paradox navigation approaches. In contrast, service organizations more often experience sustainability tensions as diffuse stakeholder expectations that are harder to frame as specific paradoxes requiring navigation.

Geographic and cultural contexts also shaped transformation approaches:

“In our Asian operations, hierarchical cultural norms significantly influence how sustainability initiatives must be introduced and implemented. Leadership endorsement is essential, and initiatives must respect hierarchical structures while still enabling participation.”

(Participant 39, Manufacturing)

These contextual contingencies help explain the quantitative finding that different capabilities have varying effects across organizational contexts. They also highlight the importance of tailoring sustainability approaches to specific contexts rather than applying universal best practices.

4.4. Temporal Dynamics of Transformation

Our longitudinal case studies revealed important temporal dynamics in sustainability transformation processes that help explain the quantitative relationships between capabilities and outcomes. These dynamics included capability development pathways, transformation phases, and evolution of integration mechanisms over time.

To provide greater precision regarding transformation phases, we identified specific markers that signaled transitions between stages. Early transformation was characterized by (1) initial recognition of sustainability tensions without systematic response mechanisms; (2) isolated sustainability initiatives lacking integration with core business functions; and (3) primarily compliance-driven approaches. The transition to advancing transformation was marked by (1) the establishment of formal sustainability governance structures; (2) the development of strategic sustainability objectives aligned with business goals; and (3) the implementation of systematic sustainability measurement systems. Leading transformation organizations demonstrated (1) proactive paradox navigation approaches embedded in decision-making processes; (2) comprehensive integration across all organizational systems; and (3) innovation-driven sustainability initiatives that created new market opportunities.

Our longitudinal case analysis revealed that these transitions typically occurred over 3–5-year periods, with paradox navigation capabilities developing approximately 12–18 months before comprehensive integration mechanisms in most cases. Organizations that attempted to implement integration mechanisms without first developing paradox navigation capabilities often experienced implementation challenges due to unresolved tensions between competing objectives.

Capability development followed different pathways across organizations. In some cases, paradox navigation capabilities developed first, creating a foundation for subsequent integration:

“We had to develop comfort with sustainability tensions before we could effectively integrate sustainability into our systems. Attempts at integration without this foundation created resistance and superficial implementation.”

(Alpha, Manager)

In other cases, initial integration efforts catalyzed the development of paradox navigation capabilities:

“As we began integrating sustainability metrics into performance reviews, tensions became visible that had previously been hidden. This forced us to develop better approaches to navigating these tensions.”

(Delta, HR Director)

These different pathways suggest that while the quantitative model identified relationships between capabilities and outcomes, these relationships may operate through different causal sequences depending on organizational context and history.

Transformation processes also displayed distinct phases, with different capabilities proving critical at different stages:

“In early phases, power mobilization was essential for getting sustainability on the agenda. In middle phases, paradox navigation became critical as we encountered complex implementation challenges. In later phases, integration mechanisms became most important for embedding sustainability into how we operate.”

(Gamma, Sustainability Director)

This phased progression helps explain the quantitative finding that paradox navigation had stronger effects for organizations at earlier transformation stages, while integration had stronger effects for more advanced organizations.

Integration mechanisms also evolved over time, typically beginning with isolated practices before developing into more coordinated systems:

“Our integration journey began with individual champions integrating sustainability into their specific domains. Over time, these isolated efforts connected into more systematic approaches, creating reinforcing cycles across governance, strategy, operations, and performance systems.”

(Alpha, Executive)

This evolution helps explain the stronger quantitative effects of integration in more advanced organizations, as integration benefits compound as practices become more coordinated and comprehensive.

5. Discussion

5.1. Paradox Navigation as a Core Sustainability Capability

This research contributes to sustainability science by empirically demonstrating the relationship between paradox navigation capabilities and transformation outcomes. Organizations that develop structured approaches to engaging with sustainability tensions achieve better outcomes than those seeking to eliminate these tensions or force false choices. This finding supports Smith and Lewis’s [

7] dynamic equilibrium model of organizing but extends it by identifying specific practices that enable productive engagement with paradoxes in sustainability contexts.

The significant relationship between paradox navigation capabilities and transformation outcomes (β = 0.31,

p < 0.01) provides empirical support for theoretical arguments about the importance of paradox approaches to sustainability [

13,

14]. The qualitative findings extend this understanding by revealing specific mechanisms through which organizations develop and institutionalize paradox navigation capabilities, including acceptance practices, both/and thinking, creative synthesis, and structural support.

Our findings advance paradox theory in three important ways. First, we move beyond conceptual models of paradox types to identify specific practices organizations use to navigate these paradoxes in sustainability contexts. This practical focus provides a bridge between abstract paradox theory and concrete organizational challenges.

Second, we demonstrate that paradox navigation requires both cognitive capabilities (ways of thinking about tensions) and structural supports (processes and systems that enable engagement with tensions). This dual nature helps explain why paradox capabilities develop unevenly across organizations and points to potential development pathways.

Third, we identify important boundary conditions for paradox approaches, showing how their effectiveness varies across organizational contexts and transformation stages. The stronger relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes in manufacturing organizations and in earlier transformation stages suggests that paradox capabilities may be particularly important in contexts with more visible tensions and less established sustainability approaches.

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that addressing complex sustainability challenges requires approaches that accommodate rather than eliminate tensions. By developing capabilities to work productively with sustainability paradoxes, organizations may achieve more substantive transformations that address multiple objectives simultaneously rather than privileging certain sustainability dimensions over others.

However, our findings also suggest potential limitations of paradox approaches for sustainability transformation. While paradox navigation enables more creative solutions to organizational tensions, it may not adequately address fundamental system contradictions that require more radical transformation. This critique aligns with concerns raised by Hahn and Figge [

23] that paradox approaches may inadvertently sustain unsustainable systems by accommodating rather than challenging their fundamental contradictions.

Future research should investigate this tension between paradoxical accommodation and system transformation, examining how organizations might combine paradox navigation with more radical approaches to address systemic sustainability challenges.

5.2. Integration Mechanisms for Embedding Sustainability

The findings identify integration practices as the strongest predictor of sustainability transformation outcomes (β = 0.42, p < 0.01), demonstrating the importance of embedding sustainability throughout organizational systems rather than treating it as a specialized function. This research advances understanding of sustainability integration by identifying four specific integration mechanisms—governance, strategic, operational, and performance integration—and demonstrating their collective importance for substantive transformation.

The finding that integration practices are the strongest predictor of transformation outcomes (β = 0.42,

p < 0.01) can be explained through a systems theory lens. Integration creates what complex systems theorists call “emergent properties”—outcomes that cannot be predicted from individual components alone but arise from their interactions [

61]. Our qualitative data revealed three specific system dynamics that produce these non-linear effects: (1) reinforcing feedback loops, where integration in one domain (e.g., governance) creates positive signals that accelerate integration in others (e.g., operations); (2) threshold effects, where integration must reach a critical mass across multiple organizational subsystems before transformation gains become visible; and (3) network effects, where the value of integration increases exponentially as more organizational functions participate in the sustainability agenda.

For example, at Gamma Corporation, the implementation of an integrated performance management system that incorporated sustainability metrics created a reinforcing feedback loop by influencing resource allocation decisions at the governance level, which subsequently accelerated the adoption of sustainable practices at the operational level. This cascading effect, characteristic of complex adaptive systems, explains why partial integration efforts often produce limited results, while comprehensive integration generates disproportionate benefits through system-wide synergies.

Viewing integration mechanisms through a systems lens also helps explain the significant interaction between power mobilization and integration practices (β = 0.19, p < 0.01). Power mobilization functions as a system enabler that alters the dynamics between integration mechanisms by changing the flow of resources, information, and legitimacy throughout the organizational system. This finding demonstrates that structural interventions are insufficient without attention to the power relationships that govern system dynamics.

This contribution extends previous research on sustainability integration [

24,

27] in several important ways. First, we specify the mechanisms through which integration occurs and demonstrate their relative effectiveness across diverse organizational contexts. Our finding that integration practices have more consistent effects across organizational sizes than other capabilities suggests their fundamental importance regardless of scale.

Second, our qualitative findings reveal that these mechanisms are most effective when implemented as coordinated systems rather than isolated practices, with strategic integration typically preceding operational and performance integration. This sequential understanding advances previous research that has often treated integration as a static condition rather than a developmental process.

Third, our identification of different integration pathways across organizational types—formal systems integration in incumbents versus built-in integration in entrepreneurial organizations—highlights the importance of contextually-tailored integration approaches. This finding challenges universal prescriptions for sustainability integration and suggests that effective approaches must align with organizational history and structure.

The significant interaction between power mobilization and integration practices (β = 0.19, p < 0.01) demonstrates that structural interventions are insufficient without attention to power relationships. This finding extends previous research by highlighting the importance of addressing both structural and political dimensions of sustainability integration.

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that addressing the gap between sustainability rhetoric and substantive action requires comprehensive integration approaches that embed sustainability throughout organizational systems. By implementing coordinated integration mechanisms that evolve over time, organizations may overcome the compartmentalization that often limits sustainability impact.

However, our findings also reveal potential limitations of integration approaches. While integration can embed sustainability within existing organizational systems, it may struggle to transform those systems when they are fundamentally misaligned with sustainability principles. This limitation was particularly evident in organizations with business models that create inherent tensions with sustainability objectives.

Future research should investigate how integration approaches might be combined with more transformative strategies that question and reshape underlying business models and organizational purposes. Such research could help address the tension between embedding sustainability within existing systems and transforming those systems to be inherently more sustainable.

5.3. Power Dynamics and Sustainability Transformation

This research advances understanding of power in sustainability transformations by demonstrating how power operates as both a constraint and enabler of change. The findings reveal that power mobilization has a significant direct effect on transformation outcomes (β = 0.27, p < 0.01) and moderates the effectiveness of integration practices.

Our finding that government support significantly strengthens the relationship between paradox navigation capabilities and transformation outcomes (β = 0.41 vs. β = 0.23) demonstrates how external power structures reshape internal organizational dynamics. Government policies provide legitimacy to sustainability advocates, creating what Avelino [

62] describes as “transformative power”—the capacity to change existing power structures rather than merely working within them. This effect was particularly evident in highly regulated industries, where government support functioned as institutional scaffolding that legitimized paradoxical approaches to sustainability challenges that might otherwise have been dismissed as unrealistic or impractical.

The varying effects of power mobilization across organizational contexts—stronger in service organizations (β = 0.35) than manufacturing (β = 0.22) and stronger in Asian organizations (β = 0.35) than North American (β = 0.22) or European organizations (β = 0.25)—highlight how power operates differently across contexts. These differences suggest that power-conscious approaches to sustainability must be tailored to specific cultural and sectoral dynamics.

Power dynamics also significantly influence inter-organizational relationships, particularly in supply chains where sustainability transformations often require coordinated action across organizational boundaries. Our findings extend Wang and Zhang’s [

31] work on inter-organizational cooperation in digital green supply chains by identifying how power asymmetries constrain transformation and how digital technologies can help rebalance power relationships. Organizations that successfully transformed their supply chains developed what we term “inter-organizational integration mechanisms”—systems and processes that created shared accountability, mutual benefits, and collaborative innovation across organizational boundaries.

As one executive in our study explained,

“We shifted from using our purchasing power to demand compliance to using our technological capabilities to enable collaboration. By implementing shared digital platforms that created transparency across our supply chain, we transformed a power-over relationship into a power-with dynamic that accelerated sustainability innovation.”

This perspective aligns with Wang and Zhang’s [

31] finding that technological, organizational, and human elements function as mutually reinforcing drivers of inter-organizational cooperation. Our research extends this understanding by demonstrating how these elements specifically reshape power dynamics to enable system-level transformation rather than merely organizational-level change.

The qualitative findings extend theoretical understanding of power in sustainability contexts [

17,

62] in three important ways. First, we identify specific strategies through which change agents navigate and reshape power relationships to advance sustainability initiatives. These strategies—strategic framing, coalition building, resource mobilization, and timing exploitation—provide practical approaches for working with power rather than simply analyzing it as a structural constraint.

Second, our findings reveal how power dynamics evolve throughout transformation processes, with sustainability advocates gaining influence as they demonstrate value and build coalitions. This temporal dimension adds nuance to existing theoretical perspectives [

30] by highlighting the dynamic nature of power relationships in sustainability transformations.

Third, our identification of persistent power asymmetries that constrain transformation, particularly regarding global supply chains and marginalized stakeholders, highlights limitations in current sustainability approaches. This finding contributes to critical perspectives on sustainability by demonstrating how power structures may undermine transformative potential.

The institutional logics prevalent in different sectors created distinct patterns of enablers and barriers for sustainability transformation. Manufacturing organizations operated within institutional fields where technical-market logics dominated, creating environments where sustainability initiatives gained traction primarily when framed in terms of efficiency, risk reduction, and competitive advantage:

“In our sector, sustainability transformation accelerated when we stopped talking about ‘doing good’ and started demonstrating how our approach reduced costs, mitigated supply chain risks, and created product differentiation. The technical-market logic that dominates our industry isn’t inherently opposed to sustainability—it just requires translation into terms that resonate with that logic.”

(Beta, Executive)

In contrast, service organizations, particularly those in healthcare, education, and social services, operated within institutional fields where professional and community logics provided more natural alignment with certain aspects of sustainability:

“Our professional ethos of care created natural receptivity to the social dimensions of sustainability. The challenge was expanding this care ethic to include environmental considerations and helping professionals see the connections between environmental health and human wellbeing.”

(Delta, Chief Medical Officer)

Public sector organizations navigated the most complex institutional environments, operating simultaneously within state, market, and community logics with shifting political priorities:

“We constantly navigate conflicting institutional demands—political pressures for short-term results, bureaucratic requirements for procedural conformity, public expectations for both service quality and cost containment, and now sustainability considerations. Successfully advancing sustainability requires finding pathways that satisfy multiple institutional demands simultaneously.”

(Zeta, Director)

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that addressing power dynamics is essential for substantive sustainability transformation. By developing power-conscious approaches that navigate and reshape power relationships, change agents may overcome resistance and create conditions more conducive to sustainability innovations.

However, our findings also suggest limitations in current approaches to power in sustainability contexts. While organizational change agents can navigate power dynamics to advance sustainability within organizational boundaries, their ability to address broader systemic power arrangements remains limited. This constraint highlights the need for multi-level approaches that connect organizational change with broader system transformation.

Future research should investigate how organizational power dynamics interact with broader power structures in society, and how change agents might work across these levels to create more fundamental sustainability transformations. Such research could help address the tension between working within existing power structures and transforming those structures to enable more sustainable futures.

5.4. Contextual Contingencies and Tailored Sustainability Approaches

This research advances understanding of contextual contingencies in sustainability transformation by demonstrating significant differences in relationships across sectors, sizes, and geographic contexts. When viewed through a systems thinking lens, these contextual variations represent different system parameters that fundamentally alter the dynamics between organizational capabilities and transformation outcomes.

Government support emerged as a particularly significant system parameter that moderated the effectiveness of paradox navigation capabilities (β = 0.41 with strong support vs. β = 0.23 with limited support). This moderating effect demonstrates how system-level factors create enabling conditions that amplify the effectiveness of organizational capabilities through multiple reinforcing mechanisms. First, government support provides legitimacy that reduces internal resistance to paradoxical approaches. Second, it creates resources that enable more comprehensive implementation of integration mechanisms. Third, it establishes institutional scaffolding that guides decision-making under conditions of uncertainty.

Table 8 below provides a summary overview of transformation patterns across organizational contexts.

This finding has significant implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically, it demonstrates that organizational capabilities do not operate in isolation but are embedded within broader institutional systems that can either amplify or dampen their effectiveness. Practically, it suggests that organizations in regions with limited policy support must invest more heavily in internal capability development and power mobilization to achieve comparable transformation outcomes.

The significant variations in capability effectiveness across organizational contexts highlight the need for systems-oriented approaches that recognize the dynamic interplay between organizational capabilities, integration mechanisms, power relationships, and external contextual factors. Rather than viewing these elements as separate variables, our research demonstrates the value of conceptualizing them as interconnected components of a complex adaptive system where interventions in one area create ripple effects throughout the entire system.

This typology of transformation patterns illustrates how organizational context shapes sustainability approaches and outcomes. Each context presents a distinct configuration of enablers, barriers, and effective practices rather than a universal transformation pathway. Large incumbents typically pursue systematic integration through formal governance structures and management systems, but face challenges of cultural inertia and competing priorities that can dilute transformation efforts. Entrepreneurial organizations leverage purpose-driven cultures and founder commitment to embed sustainability from inception, but struggle with scaling these approaches as they grow. Public sector organizations benefit from policy mandates and regulatory alignment but must navigate political cycles and bureaucratic constraints. The contrast between B2C sectors (leveraging consumer pressure and brand value) and B2B sectors (driven by client requirements and efficiency gains) highlights how market position shapes transformation incentives and approaches. Global organizations must balance the benefits of centralized governance with the need for local adaptation across diverse operating contexts. These patterns demonstrate why contextually-tailored approaches to sustainability transformation are essential—effective practices in one context may prove ineffective or counterproductive in another.

This contribution responds to calls for a more contextualized understanding of sustainability transformations [

43,

44] in several important ways. First, our empirical demonstration of how organizational context shapes both the process and outcomes of transformation challenges universal prescriptions for sustainability transformation and suggests the need for contextually tailored approaches.

Second, our identification of different transformation pathways across organizational types—systematic integration in large incumbents, purpose-driven approaches in entrepreneurial organizations, policy-driven change in the public sector, brand-driven initiatives in B2C sectors, and client-driven approaches in B2B sectors—highlights how context shapes not only the effectiveness of specific practices but the overall transformation approach.