Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Nature Education in Austria: Evaluation of Organization, Infrastructure, Risk Assessment, and Legal Frameworks of Forest and Nature Childcare Groups †

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Background

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

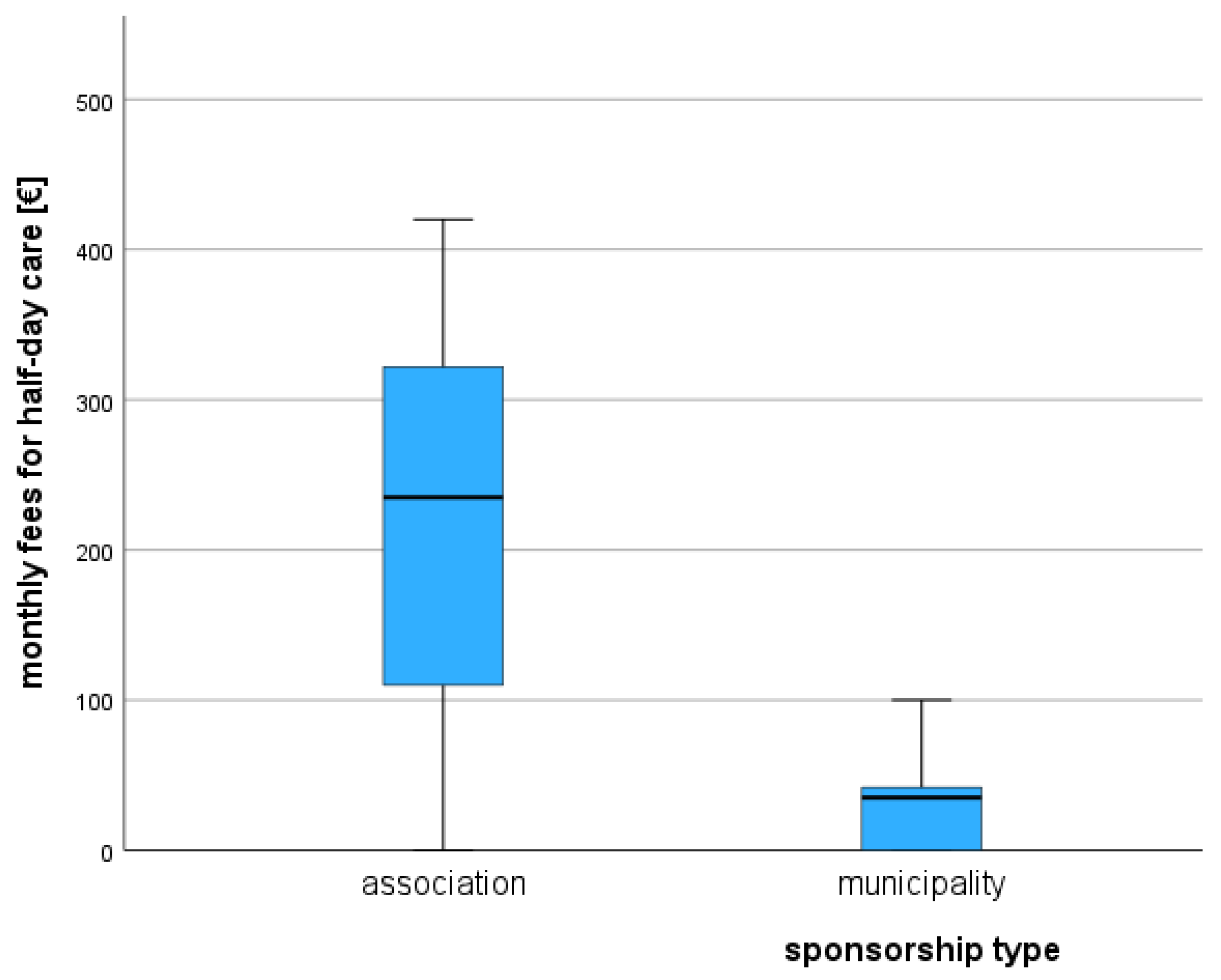

3.1. Organization

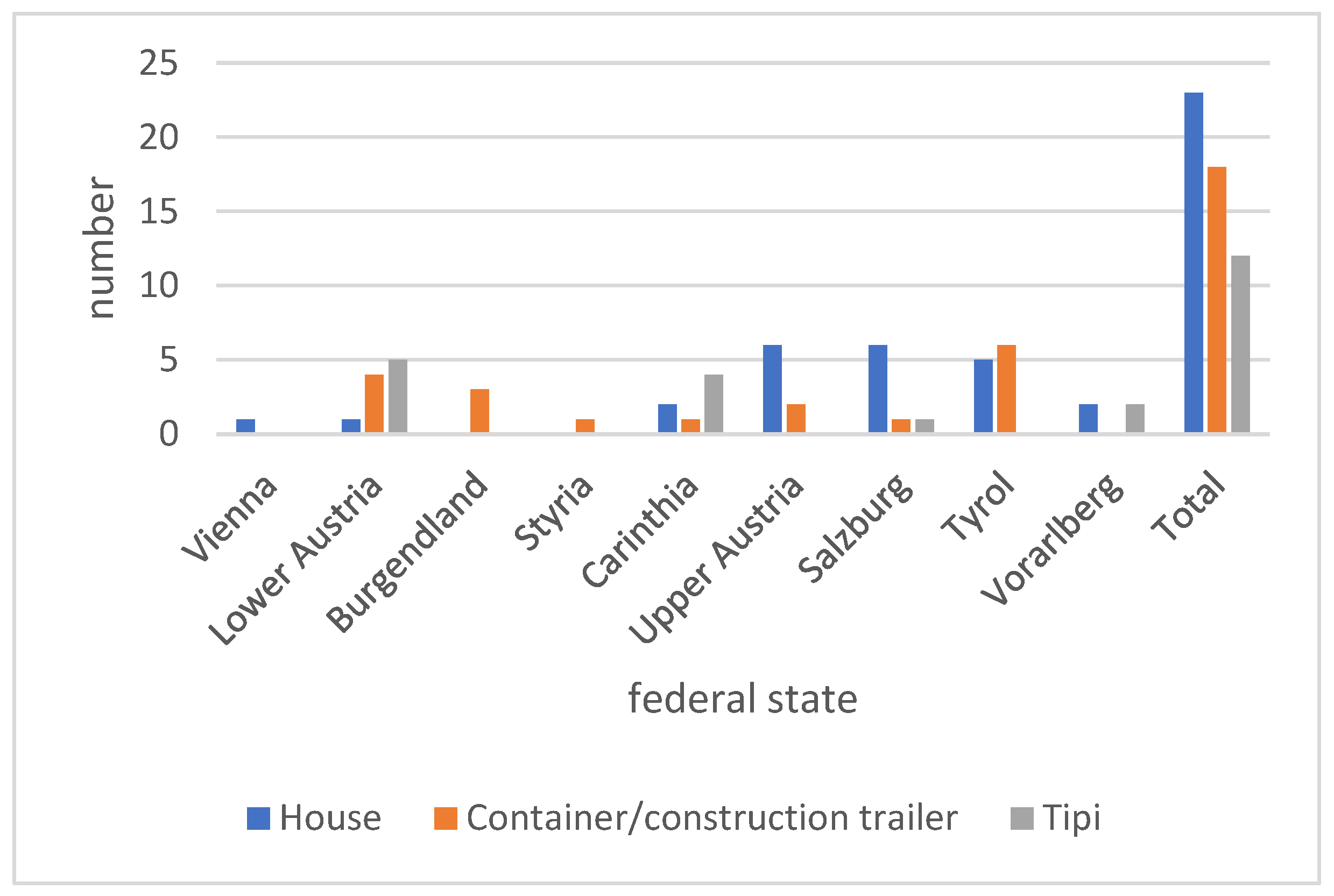

3.2. Infrastructure

3.3. Risks and Risk Prevention

3.4. Hygiene and Skin Protection

4. Discussion

4.1. Organization

4.2. Infrastructure and Safety—Comparative Perspective

4.3. Safety Approval, Infrastructure Challenges, and Legal Situation

4.4. Risk Assessment Tools and Educator Training

4.5. Hygiene and Skin Protection

4.6. Conclusions and Outlook

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, N.; Fashing, P.J.; Trosvik, P.; Stenseth, N.C.; de Muinck, E.J. A Quantitative Comparison of Patterns of Play and Conflict in Nature Preschool and Traditional Preschool Children in Norway. Int. J. Early Child. 2025, 57, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardomi, R.; Mardomi, S. Early Childhood Education Effect on Sustainable Development and Developmental Education. Early Child. Res. J. 2023, 6, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, K.; Gupta, N. An analysis of the factors affecting access to the early childhood education and care: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Early Years 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, U. Kind und Natur. 2. Auflage; Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, M.; Park, J.; Lim, W. An Investigation on Developing the Shelter and Safety Facilities of Forest Kindergartens. Prot. Converg. 2020, 5, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastran, M. Visiting the Forest with Kindergarten Children: Forest Suitability. Forests 2020, 11, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Kaga, Y. The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Raith, A.; Lude, A. Startkapital Natur-Wie Naturerfahrung Die Kindliche Entwicklung Fördert; Oekom Verlag: München, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, E.; Samantha, B.; Jenkins, J.; Perlman, M. Assessing Educator Responsivity in Outdoor Early Childhood Education and Care Settings: Validating the Outdoor Environment Version of the Responsive Interactions for Learning Measure. Early Educ. Dev. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Änggård, E. Making use of “nature” in an outdoor preschool: Classroom, home and fairyland. Child. Youth Environ. 2010, 20, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, C. Lernen mit der Natur: Einbettung der Praxis im Freien; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, P.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T.B. Towards an understanding of udeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. Education 3-13 2009, 37, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Mondal, P. Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) in India in the light of national education policy 2020: A reality check. Education 3-13 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamuk, D.K.; Olgan, R. Comparing Predictors of Teachers’ Education for Sustainable Development Practices among Eco and Non-Eco Preschools. Educ. Sci. Sustain. Dev. Pract. Among Eco Non-Eco Presch. 2019, 45, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speldewinde, C.; Campbell, C. Bush kinders: Building young children’s relationships with the environment. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2024, 40, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. Nature and Young Children: Encouraging Creative Play and Learning in Natural Environments; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Häfner, P. Natur- und Waldkindergärten in Deutschland-Eine Alternative zum Regelkindergarten in der Vorschulischen Erziehung. Ph.D. Thesis, University Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miklitz, I. Der Waldkindergarten, Dimension eines Pädagogischen Ansatzes; 7. Auflage; Cornelsen Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj-Blatchford, I. Conceptualizing progression in the pedagogy of Play and Sustained Shared Thinking in early childhood education: A Vygotskian perspective. Educ. Child Psychol. 2009, 26, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambas, A.; Antoniou, P.; Xanthi, G.; Heikenfeld, R.; Taxildaris, K.; Godolias, G. Unfallverhütung durch Schulung der Bewegungskoordination bei Kindergartenkindern. Dtsch. Z. Für Sportmed. 2004, 55, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. The Benefits of Children’s Engagement with Nature. Child. Youth Environ. 2014, 24, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Burcak, F. Young Children’s Contributions to Sustainability: The Influence of Nature Play on Curiosity, Executive Function Skills, Creative Thinking, and Resilience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaga, Y. Early childhood education for a sustainable world. In The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society; Pramling Samuelsson, I., Kaga, Y., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmcke, S.M. Children as Change Agents for Sustainability: An Action Research Case Study in a Kindergarten. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology: Faculty of Education, Brisbane City, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lettieri, R. Evaluationsbericht des ersten öffentlichen Waldkindergartens in der Schweiz. In Was Kinder Beweglich Macht. Wahrnehmungs- und Bewegungsförderung im Kindergarten; Gugerli-Dolder, B., Hüttenmoser, M., Lindemann-Matthies, P., Eds.; Verlag Pestalozzianum an der Pädagogischen Hochschule: Zürich, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Loboda, H. Are Polish Kindergartens Ready for The Outdoors? The State of (Im)Maturity of The Polish Educational System. Stud. Ecol. Et Bioethicae 2023, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMBWF. Bundesländerübergreifender BildungsRahmenPlan für Elementare Bildungseinrichtungen in Österreich; BMBWF: Wien, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schäffer, S. Naturerfahrungen und Gesundheit. Motorische Fähigkeiten, Subjektive Gesundheitseinschätzungen und Einblicke in den Alltag von Waldkindergartenkindern. Ph.D. Thesis, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn: Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät, Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schlick, C.; Bruder, R.; Luczak, H. Arbeitswissenschaft; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ÖNORM EN ISO 45001; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. Austrian Standards: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Bösken, N. Basisleitfaden Sicherheit in der Wald- und Umweltpädagogik. 2017. Available online: www.treolis.de (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Branco, A.; Mühlberger, D.; Huber, H.; Quendler, E. Charakteristika der österreichischen Wald- und Naturkindergruppen für Vorschulkinder durch Internetrecherche. In Proceedings of the 24. Arbeitswissenschaftliches Kolloquium, Vienna, Austria, 27–28 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Statistik Austria. Gemeindeverzeichnis; Statistik Austria: Wien, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, J.; Ray, K.N.; McCracken, P.; Ferrante, L.; Wardlaw, S.; Fleischmann, L.; Wolfson, D. Uptake of an Integrated Electronic Questionnaire System in Community Pediatric Clinics. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2021, 12, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.; Mrosek, T.; Martinsohn, A.; Schulte, A. Evaluation of the non-formal forest education sector in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany: Organizations, programmes and framework conditions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.A.; Atiles, J.T. Child Care Centers Licensing Standards in the United States from 1981 to 2023. Early Child. Educ. J. 2025, 53, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgaard, N.T.; Bondebjerg, A.; Svinth, L. Caregiver/child ratio and group size in Scandinavian Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC): A systematic review of qualitative research. Nord. Psychol. 2022, 75, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, A.E.E.; Rindermann, H. Kindergartenqualität abhängig von Familienmerkmalen, pädagogischer Ausrichtung und Trägerschaft. Psychol. Erzieh. Und Unterr. 2017, 64, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.; Bienenstock, A. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesetz vom 30. Juni 2010 über die Kinderbetreuung in Tirol (Tiroler Kinderbildungs- und Kinderbetreuungsgesetz), LGBl. 2010/48 idF LGBl. 2024/39. Bauliche Gestaltung, Einrichtung § 12, 4. Unterabschnitt Waldkindergärten § 21a. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/geltendefassung/lrt/20000439/kinderbildungs-%20und%20kinderbetreuungsgesetz,%20tiroler,%20fassung%20vom%2020.08.2021.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Cook, C.; Kohlmaier, V. Gefährdungsbeurteilung in Natur- und Waldkindergärten unter Berücksichtigung der Ökologischen und Gesellschaftlichen Rahmenbedingungen. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universität für Bodenkultur, Wien, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, N.J. Outdoor risky play and healthy child development in the shadow of the “risk society”: A forest and nature school perspective. Child Youth Serv. 2017, 38, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, J.W.; Hammitt, J.K.; Lim, H.W.; Geller, A.C.; Hall-Jordan, L.H. Economic evaluation of the US environmental protection agency’s sunwise program: Sun protection education for young children. Paediatrics 2008, 121, e1074–e1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostosi, C.; Simonart, T. Effectiveness of Barrier Creams against Irritant Contact Dermatitis. Dermatology 2016, 232/3, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ECEC | Intersection | ESD |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive, emotional, and social development | Integrated curriculum | Addressing global challenges |

| Holistic development | Inclusive and quality education | Sustainability practices |

| Foundation for lifelong learning | Resilience and risk reduction | Long-term impact on development |

| NUTS-1:AT 1 | Frequency | Percentage [%] |

|---|---|---|

| East Austria | 14 | 21.9 |

| Southern Austria | 11 | 17.2 |

| Western Austria | 39 | 60.9 |

| Functional Areas of Infrastructure | Average Size with SD (in m2) of Functional Areas by Infrastructure Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| House | Container/Construction Trailer | Tipi | |

| Cloakroom | 12.43 m2 (SD: 6.16) | 6.67 m2 (SD: 4.16) | 8.5 m2 (SD: 2.12) |

| Common room | 12.43 m2 (SD: 12.74) | 44.5 m2 (SD: 48.4) | - |

| Common room with a rest area | 16 m2 (SD: 16.1) | - | 12 m2 (SD: -) |

| Rest area | 1 m2 (SD: -) | - | - |

| Kitchenette | 5.38 m2 (SD: 8.52) | - | - |

| Kitchen | 3 m2 (SD: 2.83) | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quendler, E.; Mühlberger, D.; Spangl, B.; Ennöckl, D.; Branco, A. Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Nature Education in Austria: Evaluation of Organization, Infrastructure, Risk Assessment, and Legal Frameworks of Forest and Nature Childcare Groups. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156965

Quendler E, Mühlberger D, Spangl B, Ennöckl D, Branco A. Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Nature Education in Austria: Evaluation of Organization, Infrastructure, Risk Assessment, and Legal Frameworks of Forest and Nature Childcare Groups. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156965

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuendler, Elisabeth, Dominik Mühlberger, Bernhard Spangl, Daniel Ennöckl, and Alina Branco. 2025. "Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Nature Education in Austria: Evaluation of Organization, Infrastructure, Risk Assessment, and Legal Frameworks of Forest and Nature Childcare Groups" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156965

APA StyleQuendler, E., Mühlberger, D., Spangl, B., Ennöckl, D., & Branco, A. (2025). Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Nature Education in Austria: Evaluation of Organization, Infrastructure, Risk Assessment, and Legal Frameworks of Forest and Nature Childcare Groups. Sustainability, 17(15), 6965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156965