1. Introduction

The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a flagship project of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious plan of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is aimed at ameliorating trade and investment arteries across Asia, Europe, and Africa. The corridor connects China’s western Xinjiang region with Pakistan’s Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea. It includes several development projects such as highways, railways, pipelines, and energy plants that aim to improve Pakistan’s infrastructure sector and facilitate industrial and economic development [

1]. CPEC has a significant and lasting impact on trade and investment between the two countries by creating jobs and economic growth. In addition, CPEC also includes the construction of Gwadar port, the establishment of industrial zones, the upgrading of Pakistan’s aging transport infrastructure, and overcoming the issue of energy shortages. CPEC aims to integrate Pakistan more tightly into the global economy through improved regional connectivity while also offering China the shortest and safest route to its trade with the Middle East, Europe, and Africa [

2]. China and Pakistan signed multiple MOUs under the title of CPEC in 2013, and initially, the economic volume of CPEC was USD 46 billion, which reached USD 62 billion as of 2018. This investment is an energy and infrastructure project to stabilize the ailing economy of Pakistan, and it is also beneficial for China to access the Middle East and international market most shortly and cheaply. This route will take the Chinese to their energy destination within just ten days. However, Chinese ships took approximately forty days through the sea route to reach the Middle East, and CPEC would avail the least affordable and secure route to meet the energy from energy supplies without any confrontation [

3].

However, various risks are associated with mega infrastructure projects like CPEC. These challenges add to the risks related to environmental, social security, and governance (ESG) factors of the host country. Environmental risks refer to potential adverse effects on the natural environment because of the projects, such as carbon emissions, habitat loss, climate change events, and so forth [

1]. Terrorism threats, extremism and violence threats, social equality, ethnic tensions, and loss of culture and heritage are the threats to social security, whereas legal and governance risks involve issues of corruption, transparency, regulatory compliance, and political stability [

4,

5]. These ESG risks can lead to bottlenecks, delays in project timelines, cost overruns, and diminishing benefits that were expected from CPEC. Therefore, it is imperative to study how the host country, Pakistan, can mitigate and overcome these risks through innovation and sustainable practices so that CPEC projects will run smoothly and meet their delivery expectations. There have been several studies on the risks associated with mega construction projects. Yet, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study has now comprehensively developed the impact analysis of an integrated study on environmental risks, social safety risks, governance risks, and the host country’s mitigation strategies on the project performance of CPEC. This research examines the environmental risk, social safety risks, and governance risks in CPEC, a mega construction project/IJV, as per recommendations of earlier studies. Additionally, the article examines the host country’s mitigation strategies towards environmental, social, and governance risks and their impacts on project performance. This study adds to the literature by examining how the aforementioned risks relate to the host country’s mitigation strategies in undertaking international construction projects.

This study examines the impacts of ESG risk and the host country’s mitigation strategies of innovation and sustainable practices on the project’s performance of CPEC. Through this, the study will investigate and explore the ESG impact of the projects and will aim to analyze how well the innovation and sustainable practices perform in managing these risks. It will also delineate optimal practices and remedial measures that the host country may incorporate to mitigate against probable impediments to and enhance the efficacy of CPEC projects. The aim is to offer insights that can guide policymakers, project managers, and stakeholders on the significance of considering ESG risks when developing large-scale infrastructure projects and illuminate the crucial role that comprehensive mitigation strategies play in attaining sustainable and meaningful project performance. Thus, this article examines the moderation influence of the mitigation strategies of the host country to overcome environmental risks, social safety risks, and governance risks with the project’s performance of CPEC. Data were collected in a survey-based questionnaire method from 618 respondents from the academia, policy and planning, and construction industries of Pakistan. Hypotheses testing is conducted by using SMART PLS4 software based on the data obtained from the survey. Thus, this research aims to address the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1 What kind of connection exists between environmental risk and the project performance of CPEC?

RQ2: What kind of connection exists between social safety risk and the project performance of CPEC?

RQ3: What kind of connection exists between governance risk and the project performance of CPEC?

RQ4: Does the host country’s mitigation strategies of innovation and sustainable practices moderate the relationship of environmental, social safety, and governance risks with the project performance of CPEC? This study will address the above research questions by hypothesizing based on the literature. These hypotheses will be verified and tested through the data collected for this study. The subsequent sections will elaborate on the study hypothesis and framework, followed by methodology, results, discussion of the study, and conclusion.

2. Literature Review

ESG factors have become an essential component of investment decisions around the world. Specifically, investors have begun to realize that ESG elements are leveraged for greater efficiency, productivity, sustainable risk management, and operational improvement. ESG investing is a way for companies to engage in sustainability by addressing specific categories they can potentially impact, which also gives value to their investors, extending beyond just profit. Risk is defined as the chance of a negative outcome from an event and is a function of probability and impact [

6]. According to Awan et al., 2022 [

7], and Alam et al., 2019 [

8], the importance of the CPEC project is very high for Pakistan, China, and the entire world. Yet, its protracted length leaves it with several challenges and risks. These factors can be uncertain conditions, such as no or weak planning, security, social security risks, political risks, environmental protection risks, supply chain risks, legal risks, social risks, etc. Similar international projects have been studied in detail in numerous papers on the problems and risks of these types of projects. However, there is no comprehensive analysis of the effect of ESG risks and mitigation strategies on the project performance of international construction projects, particularly on CPEC in Pakistan. The study adds to the existing literature by exploring the association between the abovementioned risks and the mitigation strategies in international construction projects.

ESG has a significant and positive influence on a firm’s ability to access commercial credit financing. These can be seen in more information transparency, higher supplier concentration, lower operational risks, and fewer managerial risks. ESG levels are, therefore, not only a measure of a firm’s dedication to sustainability and social responsibility but also a shock on commercial credit financing through their impact on market trust and relationships [

9]. The acquisition of a credit facility is positively related to ESG performance. Now, with the global focus on ESG, an increasingly large number of investors and suppliers are including ESG in decision-making. Positive ESG might reduce the cost of financing [

10].

ESG ratings promote the innovation of digital technology by the company with its R&D investment and financing opportunities, and they reduce the uncertainty of ESG risk and improve corporate reputation [

11]. The innovation of digital technologies is fundamental to advancing future economic development as the world keeps moving towards a digital society. Such a juxtaposition offers a wonderful chance to delve into the interrelationship of ESG and digital technology innovation. ESG ratings help companies lead the digital technology revolution for sustainable growth in various industries [

12]. It is possible that green patenting may act as a signal for investors about how a firm is following regulatory trends and future demand, receiving a competitive advantage in more sustainable markets. Therefore, ESG-related innovation reflected in green patents is presented as an important link between sustainability strategy and firm value [

13]. The ESG-driven companies perform better in future innovation performance and no worse for labor productivity, exporting, or survival than innovative companies that are not ESG-driven [

14]. Yang et al., 2021 [

15], describe the practical implications of different innovative and sustainable practice approaches in similar infrastructure and development projects as essential to further develop or decompose these theoretical constructs and guide strategic options generation. Evidence from Asia and Africa megaprojects has identified that inclusive governance arrangements, environmentally sustainable design, and ESG-integrated finance mechanisms can significantly improve the resilience and social and economic acceptance of projects [

16].

In addition, there has been limited strategic integration of ESG principles into CPEC risk management to date. While ESG frameworks have received momentum at the global level, the adoption of ESG in the planning and implementation of megaprojects in politically unstable regions such as Pakistan is hampered by institutional and governance constraints. The incorporation of ESG considerations within project planning and monitoring procedures is critical to the success of such projects and the overall benefits generated. Nevertheless, there are some barriers in terms of the application of ESG principles, such as general unawareness among the project stakeholders and insufficient legislation. The ESG will increasingly play a transformative role in driving the green transition, but this will depend on its full integration into project planning, monitoring, and reporting. In this way, CPEC renewable energy projects can be armed to play a key role in a sustainable future while also making certain that they achieve their economic and social goals [

17]. There is thus a call for detailed research investigating the performance of various types of innovations and sustainability strategies in the specific social, political, and environmental context of CPEC. Comparative empirical research could shed light on which mechanisms achieve the best trade-off between development and containment, which can inform academic thinking about resilience and the development of infrastructure policy that is more resilient.

Risk management is a fundamental part of planning and executing many national or international projects [

18]. The construction sector is more dynamically complex than any other sector, leading to a higher risk of construction project breakdown [

19]. There are numerous issues and misinterpretations of risk management in Pakistan and other developing countries, such as social, legal, and political, and several other risk identifications and assessments [

20,

21]. Mitigating the identified risks in international joint ventures (IJVs) before project execution can serve as a significant benefit for new international construction projects. Thus, we need research to find ways to mitigate such risks to be carried out in developing countries. CPEC is a significant project for Sino-Pakistan; however, it also has several challenges and risks because of its length. These challenges and risks have not been well-defined or have limited interruption of project risks, such as poor governance, security issues, environmental risks, governance risks, social risks, and financial risks [

7,

8]. There is no comprehensive research that integrates the ESG aspects in the context of the infrastructure project of CPEC. Although previous research has focused on environmental risks, social challenges, and governance issues of CPEC, they have not studied these components collectively in depth. Furthermore, the literature available conveniently ignores the specific mitigation measures that the host country (Pakistan) has taken to identify the risks that exist for such projects and their effectiveness in improving such projects. The present research fills this void and estimates the effects of the environmental risks, social security risks, governance risks, and host country mitigation strategies on the project performance of CPEC. One of the main goals of CPEC is to stimulate economic development in Pakistan through the construction of new transportation links, which will help move goods more efficiently and attract foreign direct investment [

22]. CPEC investment accounts for approximately 19% of Pakistan’s GDP [

23]. It has the potential to create more industrial production, employment, and income generation. Thus, the second development phase of the CPEC objective is to focus on Business-to-Business investments [

24] to fortify linkages and support industrial uplift for economic development.

The role of CPEC in strengthening Pakistan’s construction sector by increasing investments, infrastructure development, generation of employment opportunities, and transfer of technology. However, they also point out the challenges and risks associated with CPEC, which include social safety issues, environmental challenges, and sustainable development. Tied with the tremendous potential of CPEC for economic growth and development, the project is subject to multiple risks that are likely to have an output on the project performance of CPEC [

25]. These risks encompass a wide range of concerns, but environmental, social safety, political, and legal risks are paramount. Such kinds of risks can be mitigated and managed by sustainable construction and development strategies of the host countries. It was highlighted in previous studies that in mega construction projects, risks like political risk, social safety risk, and legal risks are generally more severe and sensitive [

26,

27]. Regrettably, previous researchers have made scant attempts to investigate the impacts of project risks in international joint ventures (IJVs) [

21]. As found in prior studies, potential threats in the international construction industry or IJVs are linked to social safety, political stability, and environmental- and governance-related aspects [

26,

28]. To ensure smooth foreign direct investment in IJVs, particularly related to the construction industry, these risks should be explored, and suggestions should be made on how to mitigate them [

29].

2.1. Environmental Risks

Infrastructure is crucial for economic development, and the construction sector is the backbone of infrastructure development. However, this is also a significant cause of environmental destruction. It accounts for fifty percent of carbon emissions and all solid waste and also twenty to fifty percent of the world’s natural resources consumption [

30]. It is among the largest contributors to air, noise, water, light, and waste pollution. Uncontrolled construction activities negatively influence flora and fauna, ecosystems, and the overall natural environment. CPEC is a megaproject, and its development consists of several construction projects, including industrial, energy, roads, railways, dams, ports, and various other development projects in Pakistan [

3]. Like other mega construction projects, CPEC poses many environmental risks, such as deforestation, ecological degradation, adverse impacts on the local ecosystem, water pollution, and air pollution [

31]. While the CPEC projects will improve the social and economic profile of the country, this construction will face many environmental challenges, such as a loss of biodiversity, carbon emission, and agricultural land deterioration [

32]. CPEC road project construction has played a major role in creating such problems, including loss of biodiversity, water and soil pollution, carbon emissions, and affecting agricultural land [

33]. Also, some other adverse environmental effects are air pollution, noise pollution, forest land degradation, natural resources depletion, and the generation of a huge amount of waste [

34]. Environmental degradation is exacerbated by the melting of glaciers and widespread deforestation [

35]. The northern areas of Pakistan, especially Gilgit-Baltistan, are home to around 5000 glaciers, which is the largest glacier deposit in the globe except Antarctica [

36]. The rapid melting of the glaciers from human activities has led to serious challenges to climate change and flooding [

37]. Sadaqat claims that in the Oghi, Darband forests and within the limits of Battagram, Kohistan, and Torghar districts altogether, 13,784 trees were cut down in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Upper Hazara region [

38]. Likewise, 10,075 trees were cut down from 28 villages along the CPEC route in the Siran forest division of Mansehra. The loss of this biodiversity has devastating effects on local communities that depend on access to forest resources and are at heightened risk of natural catastrophes such as floods, as well as on the livelihoods that depend on these ecosystems.

In addition, the construction of CPEC has been linked to environmental dangers such as carbon emissions, deforestation, loss of local biodiversity, and climate change [

39]. This environmental risk factor in the CPEC construction process needs to be assessed, as national progress in economic development is futile without ecological conservation. As CPEC passes through various ecological regions, it poses threats to the local environment. Incorporating sustainable construction practices not only contributes to safeguarding essential ecosystem services but also returns the favor by enhancing project sustainability in the long term [

24]. Fossil fuel consumption, deforestation for road and railway developments, and coal-fired power plants built on the whole infrastructure can have long-lasting impacts on a country’s climate. For instance, over 54,000 trees were cut in 2020 only for road infrastructure projects in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa [

40]. The rapid loss of these trees would endanger both agriculture and climate [

31]. Big transportation systems such as roads and rail systems that are built alongside other infrastructure can lead to adverse impacts on habitats, which eventually results in a loss of biodiversity. Some plant and animal species, including endangered ones, live in the areas through which CPEC passes. The construction of roads and other transport infrastructure for CPEC will threaten the region’s biodiversity and environmental sustainability. CPEC will accelerate the process of deforestation, which is likely to result in further floods and faster melting of glaciers [

41]. These implications highlight the necessity for practices of sustainable development to curb climate and environmental impacts, safeguarding the environmental resilience of the region, although other studies, such as Maqsoom et al. [

27], recognize CPEC as detrimental to indigenous flora and fauna. Therefore, these environmental risks represent several threats to the project of CPEC. Hence, the following hypothesis is formulated in this study:

H1: Environmental risk negatively affects CPEC project performance.

2.2. Social Safety Risks

Social risks in the construction industry and highway and railway projects, which have an extensive geographical scope, are common examples of such social problems [

32]. These risks can be harmful to the aim of projects. Previously, various Chinese construction companies have faced huge risks regarding social safety risks, including kidnapping, extremism, terrorism, and armed conflicts in Afghanistan, Sudan, Pakistan, India, Yemen, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Mali. In the case of the CPEC project, there are five major social risks, namely terrorism, armed conflicts, violent protests, crime, and kidnapping. International and national firms are involved in the CPEC project. International companies must carefully assess security measures to deliver these types of projects successfully. The personnel and assets of these organizations are under significant threat due to the various insecure conditions surrounding CPEC [

42]. In addition, there are multidimensional organized religious and ethnic groups that threaten the security and stability of Pakistan, and tensions with neighboring countries are also important external factors that add social risks to Pakistan. Typically, infrastructure projects consist of four stages in their life cycle, namely initiation, planning, executing, and closing. Social risks can impact project performance across all four stages. Lack of risk management is frequently the cause of multiple social events [

43]. Terrorism and political violence like social unrest and civil war, as well as adverse changes in host country policy, are examples of socio-political risks faced by Chinese companies [

44]. The bilateral relationship between the home and target countries is an important aspect to consider for firms engaged in overseas investments, as Chinese firms often emphasize political risk and downplay social issues [

45].

Social risks have a significant role in the quality and cost of the projects, especially in the case of mega infrastructure projects. Furthermore, social risks involve security risks that can adversely impact the overall project performance [

21]. Hence, the host country should focus on minimizing potential risks for facilitating investment in IJVs such as CPEC. The failure to pay such attention will lead to corresponding social risks, which will eventually cause project failure and lead to huge economic losses [

46]. Therefore, without effective management of security challenges, CPEC can never become a success. China and Pakistan do not only face threats from outside but also from their soil. China’s Xinjiang province is a security black spot, while Pakistan’s tribal areas face security challenges. These security problems are one of the underlying causes behind the project’s progress in Pakistan. There are increasing worries about militant groups and nationalist movements in Baluchistan, Pakistan. As a substantial part of CPEC is traversing through Pakistan, social security concerns in the country are pivotal for the project’s performance. From the perspective of regional sustainable development, we can foresee potential social and economic impacts for better and for worse. Incorporating social and economic impact assessments as part of sourcing strategies is one way of maximizing the return on development projects to the local communities [

47]. Some researchers also extended the concept of vulnerability by examining the social environment [

48]. Hence, such a social rate of risk is directly linked to the CPEC project. Based on the above, the following hypothesis is formed in this study:

H2: Social safety risk negatively affects CPEC project performance.

2.3. Governance Risks

Governance is a legally, politically, and academically contested concept. Usually, in academia, governance is located with social networks, cultural values, and normative notions of law-and-order subjective categories that are thus hard to measure [

49]. The CPEC project appears to be experiencing some governance-related issues that may impact its effective execution and strategic viability. Central issues are the lack of transparency in project agreements and financial terms, the limited participation of provincial parties in decision-making, and the weak institutional capacity to handle the development of infrastructure on a grand scale. There are also concerns about corruption and legal and regulatory uncertainties of the project, all of which have called into question whether any of this activity will be subject to civilian oversight. These issues add pressure to political disharmony, social unrest, and investor confidence, leading to the performance of a project and the society’s belief in the government’s decision-making process [

50,

51]. Scholars highlight the governance risk, including poor governance, low institutional capacity, transparency issues in CPEC investments [

52,

53], the incoherence of climate change policies [

54], low stakeholder capacity [

55], inefficient implementation of policies and plans [

56], and difficulty in integration into environmentally friendly policies [

54], It is these issues that act as major bottlenecks in making CPEC sustainable and ensuring good governance. In addition, poor governance, such as lack of transparency, bureaucratic and legal issues [

57], and weak institutional framework [

58], could lead to fragile institutions and political instability in BRI countries, including Pakistan [

59]. Zhang et al. [

44] argue that weak governance and political instability as institutional and administrative issues have added to the challenges of CPEC’s in-depth construction and implementation. But in this particular case of the CPEC project, the risks and challenges to Beijing’s investment in Pakistan are even more significant, with corruption, governance issues, and the failure of public institutions being further hurdles to the Pakistani government and economic development [

60].

Cost overrun and time delays are key governance risks to lead a project termination in the construction industry [

42]. Weak political institutions and political instability are significant barriers to the country’s ability to generate critical resources, including physical and human capital, and stifle innovation and the uptake of technology. This also facilitates jurisdictional expropriation and manipulation, as well as the degradation of ecological quality through neglecting environmental externalities and the impacts of economic growth [

61]. Several negatives came after the MoU agreements during the initial phase. Some of the political parties of Pakistan were not consulted properly, according to [

62], which raised a few issues of security, safety, corruption, governance, execution of the projects, and the legal side. In addition, other concerns were raised, which included the unequal distribution of project benefits, interferences, civil–military tensions, an anti-democratic perception, and route selection issues regarding opting for the eastern corridor route instead of the previously agreed western corridor route [

63]. Governance-related risks in CPEC are political instability, corruption and lack of transparency, regulatory issues, cost overrun, and project delays. Poor governance can result in inefficiencies, corruption, and lack of accountability that can put the project’s success at risk. Moreover, CPEC is not a simple cooperative project; it involves multiple stakeholders, including governments, private companies, and international partners. Thus, it is vulnerable to governance dilemmas. Corruption and bureaucratic inefficiencies can delay project completions, inflate costs, and lead to poor-quality infrastructure. Moreover, weak institutional structures and political instability in Pakistan can slow down decision-making and project implementation. On the other hand, governance risks could stem from concerns surrounding regulatory frameworks characterized by ambiguous or inconsistent policies, which can contribute to confusion and uncertainty for investors and contractors. Broadly, to mitigate governance risks will require robust institutional frameworks, transparency in processes of decision-making, and mechanisms for accountability. This step is critical and based on the perspectives of all stakeholders and incorporating project best practices, as well as ensuring strict anti-corruption measures are in place. Hence, such a social rate of risk is directly linked to the CPEC project. Based on the above, the following hypothesis is formed in this study:

H3: Governance risk negatively affects CPEC project performance.

2.4. Mitigation Strategies of Innovations and Sustainable Practices of Host Country

Innovation and sustainability practices result in major practical implications such as increased competitiveness, better management processes, efficiency in operations, and better results for the organization and the environment around them. The adoption of sustainable practices helps raise awareness of sustainability in terms of waste emissions reduction, efficient resource utilization preference for renewable energies, and other measures that reduce the impact of business activities on the environment [

64,

65]. Therefore, by definition, risk mitigation strategies in development projects refer to actions taken to minimize negative effects. The construction activities of CPEC have detrimental environmental consequences in Pakistan, such as biodiversity loss, water pollution, air pollution, and deforestation. It should be adopted sustainable practices to overcome the environmental risks [

66]. Thus, there is a need to make strategies to minimize environmental risks through sustainable construction practices and social and governance risks by engaging stakeholders, capacity building, and transparency, respectively. There is a need to make a robust plan to ensure transparency and counter-terrorism strategies to overcome the governance and social safety risks in CPEC [

25]. Sustainable development is not something that just happens on its own; it demands a holistic approach that considers the intersection of social, environmental, and economic factors. How successful this will be depends on involving stakeholders at every level of the decision-making process. The CPEC is a significant economic and infrastructure development project that marks both prospects and challenges in achieving sustainable development [

67,

68]. Stable policies provide the foundation for long-term planning, investment, and the development of regulatory frameworks to address environmental issues. However, various environmental resistances can influence the efficiency of stable programs [

69].

The CPEC traverses Pakistan’s most volatile province of Balochistan, which is known for its vulnerability to ethnic strife, terrorism, and separatist movements [

25]. Pakistan’s internal security has remarkably improved due to several military operations against terrorist organizations. Major hurdles persist in accomplishing the execution of mega development projects for CPEC. Although a dedicated security force has been set up to provide security at project sites and for Chinese personnel, terrorism from Afghanistan and the difficult landscape of Baluchistan continue to pose security threats. The federal government has set up the Special Security Division, a military command to protect CPEC and the workforce as a whole, to meet these specific challenges. Pakistan’s security agencies have also carried out counterinsurgency operations against outfits such as ETIM and the TTP, but much more is needed to improve the security situation. Overcoming terrorism is crucial for the successful establishment of the CPEC. Even though Pakistan faces a grave challenge from militant groups such as the BLA, the BRP has the potential to further expand its influence in the region. To counter the worrying terrorist threats, Pakistan launched a nationwide crackdown against these groups by sanctioning Operation Azm-e-Istehkham, but opposition political parties denounced the operation, invoking the risk of human rights abuses, the economic crisis, and collateral damage. The criticism notwithstanding, Pakistan has also embarked on a recovery plan to restore affected regions, encourage economic development, and support displaced populations. In sum, an effective counter-terrorism strategy would require cooperation with China, critical to guarantee the long-term sustainability of CPEC. In light of these challenges of collective action, Huang [

70] stressed how China desired not just to mitigate the political risks from the BRI member countries but also to correct itself. As a case in point, Boni and Adeney [

71] observed the PTI government had created a CPEC Authority staffed by civil–military personnel to fast-track project implementation. According to Yigit [

59], the Pakistani government established a special security division to mitigate the social security risks along the CPEC. China had started Joint Cooperation Committee (JCC) meetings that engaged multiple stakeholders on one platform and deliberated on a variety of inter-governmental issues ranging from transparency, decentralization, routing, project proposals, security, and institutional legalities through discussion portals. Other authors, such as [

71,

72], study the impact of governance weaknesses and political instability as significant hurdles to the economic corridor and national interests in Pakistan, potentially restricting the number of economic benefits for both nations. Government organizations need to tackle these challenges through risk management best practices and stakeholder engagement. Ultimately, CPEC embodies a double-edged sword for Pakistan’s construction sector that must navigate both pitfalls and prospects for a sustainable future.

Additionally, the diverging bureaucratic nature of government frameworks can create barriers to the conversion of stable policies to action, so even the most stable climate policy may not be executed in action due to complex administrative processes, competing interests, and divergent regulations [

73]. In the same way, management practices that are specifically associated with sustainability-related risks must comprise governance mechanisms and monitoring and collaboration-based mitigation [

74]. Moreover, balancing economic growth and environmental sustainability will continue to be a complex issue that requires coordinated actions across multiple governance levels [

75]. Project management risk can be defined as the risks involved in the planning, execution, and operation phases of energy projects; these risks can lead to delays and cost overruns [

76]. There are many potential causes of project design and construction delays, such as permitting issues, supply chain disruptions, and unexpected technical challenges. Cost overruns are a result of poor cost estimates, changes in project scope, and unforeseen expenses. Thus, either of them leads to increased project costs and delayed revenue. Development projects must be completed on schedule and within budget, which can only be achieved through effective project management [

77]. This involves extensive preparation, prudent resource management, and careful risk control. Failure of effective project management leads to high cost, inefficiency, and poor execution of projects.

Innovation and sustainable practices play a pivotal role in risk management and improving project performance. These practices have large potential to support the development of equitable systems to ensure successful resource allocation, improved management processes, innovation, and sustainability. When real-time threat scenarios have come into play, the standard risk management approach is adequate but has shown unsuccessful relevance. Innovative technologies like Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, and Blockchain are disrupting this space in making the adaptation of risk management process more effective. AI applications can continuously monitor for risks, such as crowd density by events not to be exceeded or delays in the supply chain. Predictive analytics have been shown via case studies to reduce project delays by as much as 20% in such industries as manufacturing and logistics [

78]. In the context of cost savings by harnessing renewable energy solutions in their event operations, the company achieved 30% decreased operational costs over five years, demonstrating environmental and economic advantages. Using this kind of data makes a strong case for implementing these techniques [

79]. The IoT integration and practical controllability are increased by IoT devices; for example, determining measuring devices performance tools to avoid occurrences of accidents [

80]. Blockchain technology allows secure data operation and provides a permanent record of supply chain activity, which mitigates risks associated with fraud and inefficiencies [

80]. For example, an AI system with IoT sensors can help with predicting the exact prevention of equipment breakdown and save project costs and time. For mitigating the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks of CPEC, various measures have been introduced, such as EIA (environmental impact assessment), security arrangements, or setting up oversight mechanisms like the CPEC Authority. However, implementation is often limited by weak enforcement and insufficient stakeholder engagement. For example, the ADB’s projects in Central Asia and Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway show more structured and transparent strategies and attitudes focused on the importance of clear timelines, monitoring, and community engagement. These global cases are good examples for CPEC to follow to enhance its ESG risk management and project sustainability. Based on the above, the following hypothesis is formed in this study:

H4: The host country’s mitigation strategies of innovations and sustainable development mediate the relationship of environmental risks with the project performance of CPEC.

H5: The host country’s mitigation strategies of innovations and sustainable development mediate the relationship of social safety risks with the project performance of CPEC.

H6: The host country’s mitigation strategies of innovations and sustainable development mediate the relationship of governance risks with the project performance of CPEC.

2.5. Project Performance

The construction industry is one of the major industries across the world. It accounts for roughly 10% of Pakistan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Thus, the construction industry needs to assess the impact of project performance that can negatively or positively impact national economies [

81]. Project performance is defined as a part of performance management that uses the assessment results relevant to the objective that articulates the current status of the project or the expected future direction of the project. Project performance is a critical factor for the construction industry across the world, as it helps project teams track progress and understand the project’s trajectory. The project performance is commonly measured according to the objectives of the projects, which can be time, cost, quality, client satisfaction, etc. [

82]. Hence, so many studies about project performance effects in developing countries are carried out. Poor project performance often leads to cost overruns and time delays [

83]. Other critical challenges are poor project quality, ineffective management of construction contracts, client satisfaction, poor financial management systems, shortages and wastage of materials, and variation in site conditions [

84]. Hoff et al., 2015 [

85], and Ameashi et al., 2009 [

86], contended that the ESG risks have gained prominence among project management concerns as their combined impact is more widely recognized as having implications for project success. Recent research demonstrates that ESG risks are not in silos and work in an interdependent manner. For instance, poor governance fosters environmental mischief, incurring a social counteraction. Likewise, environmental depletion can lead to conflicts within a society, which could surface shortfalls in governance. Such interrelationships produce a cascading risk environment, whereby inaction in one dimension may accentuate risks in the other dimensions and, in the end, undermine project performance in terms of cost, time, quality, and sustainability. A way of moving forward is the greater call for a system-thinking viewpoint from the literature to understand these dynamic interrelationships. By considering ESG risks, firms can predict knock-on effects more easily, leading to more robust planning and execution of projects. A comprehensive consideration of ESG risks is, therefore, important to secure the project over the long term and to bring together all stakeholders.

In the construction industry, one of the main objectives is to finish a project within the allocated budget. Xu et al. highlighted that the difference between the planned budget and the actual budget is a critical factor in the assessment of a project’s performance [

87]. Similarly, a project getting completed on time is paramount, as the stakeholders and the public usually gauge the success of a project based on whether or not it has met its deadline. Li et al. showed that comparing planned schedules with actual completion times for the project is one of the most efficient techniques used in assessing a project’s performance [

88]. However, project performance is affected by various risks. Therefore, it is vital to look into the effects of various environmental, social safety, and governance risks and the host country’s mitigation strategies of innovation and sustainable practices for analyzing project performance. The CPEC is providing considerable benefits to the construction industry in Pakistan but has also brought various critical risks. These activities cannot take place without proper planning and collaboration between the actors involved in the project. With the mandate being this massive and the complexities involved with CPEC, it should work in close collaboration with departments of the government, private companies and organizations, and trading corporations. Such a lack of coordination has led to cost overruns, delays in projects, and quality problems [

25]. If these projects are successfully executed, the social and economic conditions of Pakistan will improve significantly. This megaproject provides multiple direct benefits, including attracting more investment and job opportunities within local communities. Furthermore, it enhances transportation and integration systems aligned with infrastructure modernization [

89]. CPEC provides a great opportunity to contribute towards the sustainable development of the region and Pakistan; however, CPEC also poses new challenges that need to be effectively managed [

1]. As a global interest project, CPEC must consider these risks and impacts on the project performance; thus, this research uses environmental, social safety, and governance risks and host country mitigation strategies to evaluate the project performance of CPEC. It has been shown that integrating environmental sustainability into the project lifecycle from planning to execution and operation could be good for the project performance due to better community acceptance, reduction in operation cost, and better overall reputation of CPEC.

4. Data Analysis

To empirically assess the conceptual framework developed in this study, data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) via SmartPLS4.1 software. This approach is particularly suitable for exploratory and predictive research involving complex relationships among latent constructs. The analysis aimed to examine the influence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks and the mitigating role of host country innovation and sustainability practices on the performance of CPEC projects. The following section presents the results of the measurement and structural model assessments, ensuring both the reliability and validity of the constructs and the robustness of the hypothesized relationships.

4.1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

Data was analyzed by using SMART PLS 4, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). This process allowed for the simultaneous evaluation of both the measurement and the structural models. This is a model that describes the interrelationship of the ESG risks, mitigation measures, and project performance for CPEC projects. In this study, the independent variables for model specification in this study are ESG risks and the mediation variable as a mitigation strategy, and the project performance of CPEC is the dependent variable. A measurement model test was used to establish the construct’s reliability and validity. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability were used to assess internal consistency, and the average variance extracted (AVE) was computed to test the convergent validity of the model. Discriminant validity was further tested using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. Path coefficients were calculated to assess the strength and direction of the relationships in the structural model between the constructs. A structural model was established, and the path coefficients were examined to explore the relationships between the constructs. The significance of the path coefficients was evaluated by bootstrapping with 5000 resamples. Finally, the overall fit of the model was evaluated using multiple fit indices, such as the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

4.2. Assessment of the Outer Model (SEM)

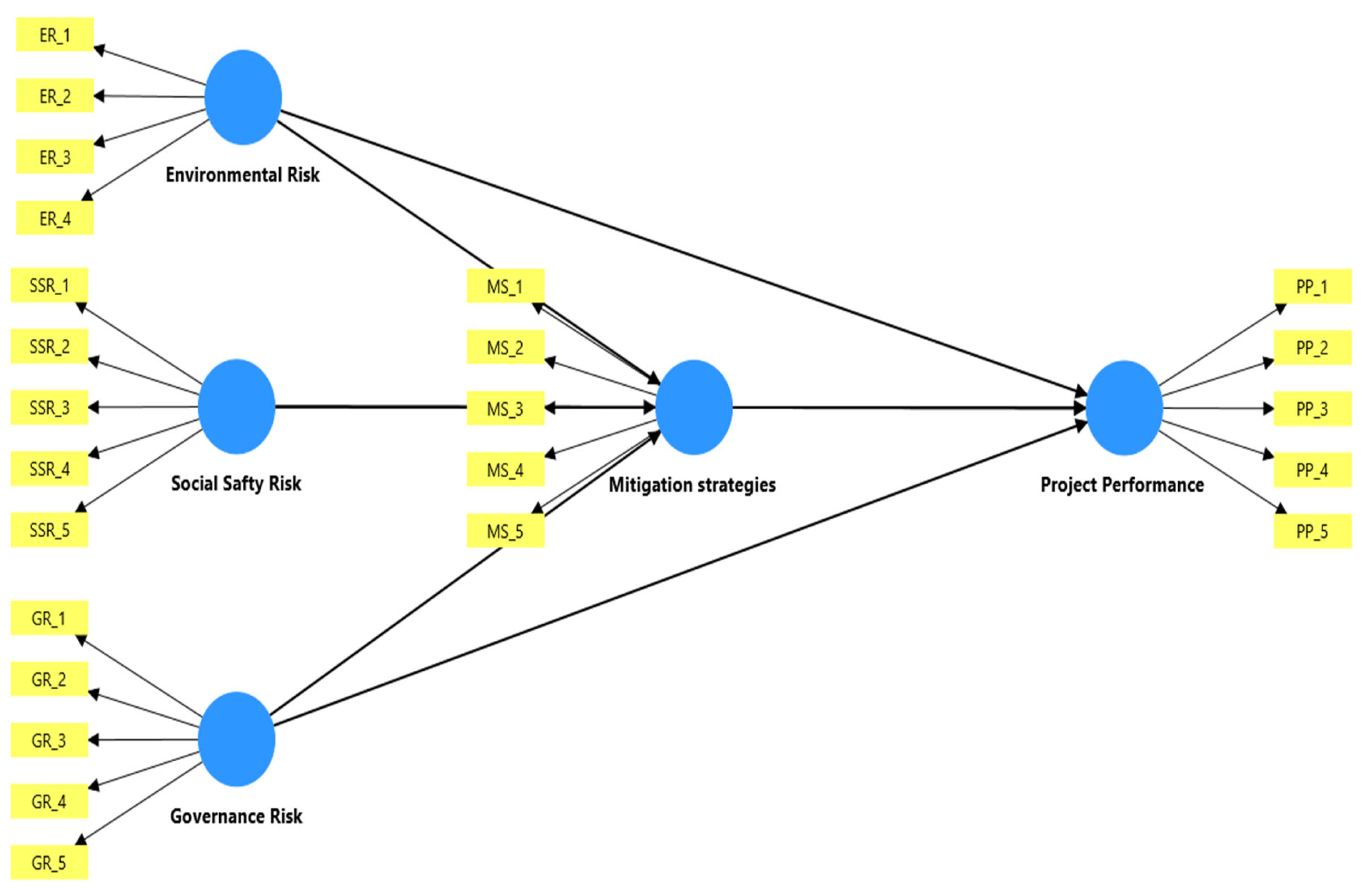

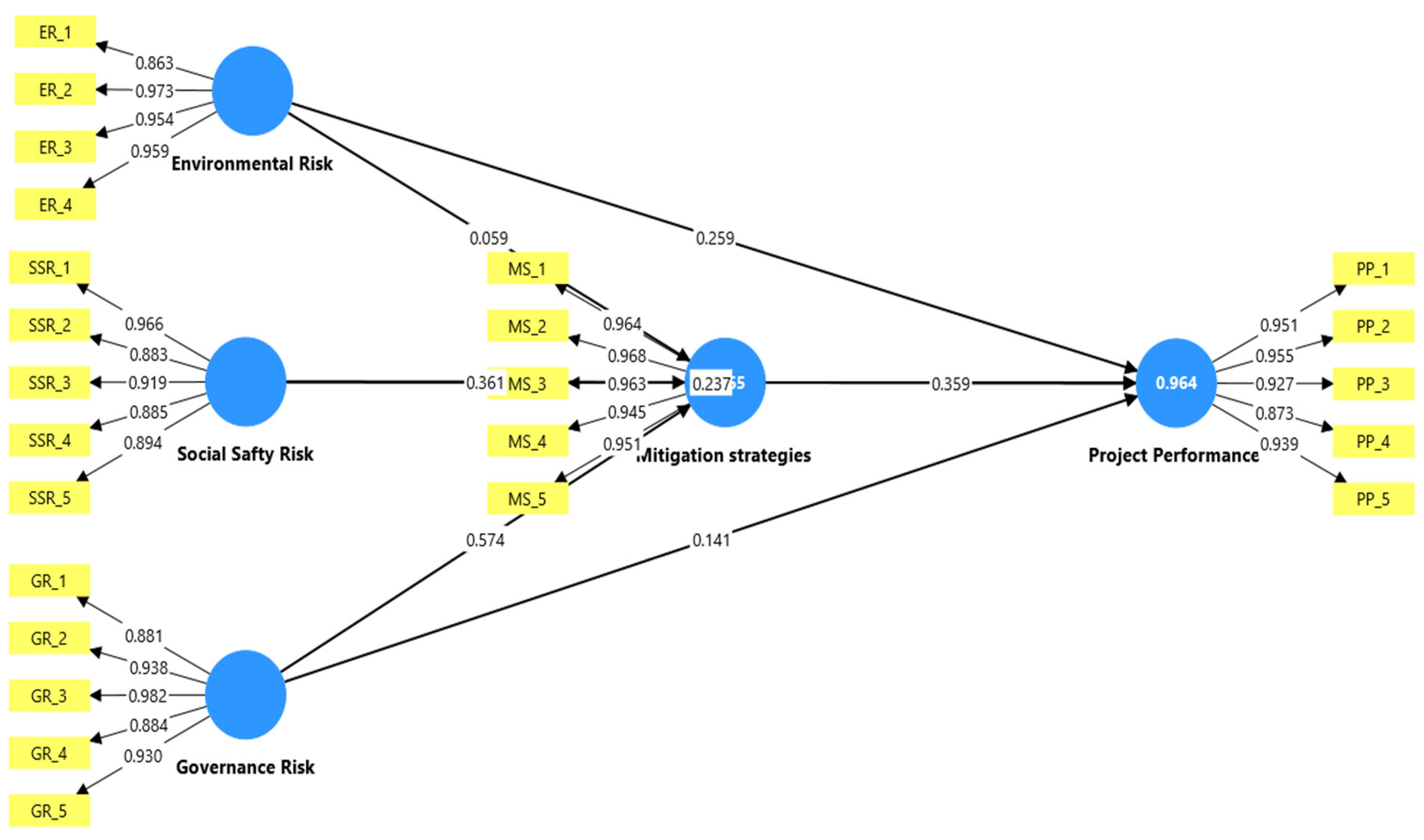

The model resembles a Structural Equation Model (SEM) with four latent variables, namely environmental risk, social safety risk, governance risk, and mitigation strategies, and one observed variable, which is project performance. Each of these variables is represented as a latent construct, with the paths indicating the relationships between them. The strength and direction of the relationships are measured by the path coefficients displayed next to the arrows. Environmental risk (ER) is positively associated with mitigation strategies (MSs) to prediction power 0.059, which indicates a very weak relationship between these two constructs. The items under environmental risks (ER_1, ER_2, ER_3, and ER_4) have strong loading on their respective construct, with the values ranging from 0.863 to 0.973, confirming that this construct could be utilized to serve the purpose of measuring environmental risk.

Social safety risk (SSR) has a strong relationship with mitigation strategies (MSs), with a path coefficient of 0.361, indicating a moderate effect on mitigation strategies. Social safety risk (SSR) items (SSR_1, SSR_2, SSR_3, SSR_4, SSR_5) load strongly, ranging from 8.83 to 9.66, which demonstrates their good representation of the social safety risk construct. Governance risk (GR) shows a moderate effect on mitigation strategies (MSs), with a path coefficient of 0.574, indicating a significant association, and the items under governance risk (GR_1, GR_2, GR_3, GR_4, GR_5) reveal high loading from 0.881 to 0.982, contributing to the support that governance risk is indeed a strong contributing factor. Mitigation strategies (MSs) also demonstrate a strong relationship with project performance (PP) based on the path coefficient of 0.359, which indicates that the mitigation strategies improve the project performance. The loadings of the MS items (MA_1, MS_2, MS_3, MS_4, MS_5) range from 0.945 to 0.964, confirming the alignment of all items with the mitigation strategies construct. PP_1 to PP_5 = project performance (PP), with all items from PP being a solid measure of project performance (for PP, loadings range from 0.873 to 0.951). Mitigation strategies (MSs) have a strong relationship with project performance (PP), with a path coefficient of 0.359, suggesting that mitigation strategies positively impact project performance. The loading values for these MS items (MA_1, MS_2, MS_3, MS_4, MS_5) range from 0.945 to 0.964, which indicates their strong alignment with the mitigation strategies construct. Finally, project performance (PP) is significantly represented by its items (PP_1, PP_2, PP_3, PP_4, PP_5), which have loadings of 0.873 to 0.951, reflecting the importance of these items in capturing the overall performance of the project (

Figure 2).

4.3. Reliability Analysis of Construct

Cronbach’s alpha values and reliability measures for environmental and governance risk and mitigation strategies, project performance, and social safety risk are indicated in the table below (

Table 2). Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal consistency, which refers to how well a set of items measures a single unidimensional latent construct.

For all variables, Cronbach’s alpha values vary between 0.948 and 0.978, suggesting a high internal consistency. In particular, the data within this study variable (mitigation strategies) has the highest value of 0.978, labeled Cronbach’s alpha, followed by a governance risk value of 0.956 and a project performance value of 0.960. Environmental risk and social safety risk show values of 0.954 and 0.948, respectively, still showing great reliability. For reliability, values in the second column (reliability) are also very big numbers, which indicates that the scales used to measure each variable are consistent and reliable. All variables have reliability values ranging between 0.950 and 0.978, indicating high reliability of the measurements with respect to the constructs (

Table 3).

4.4. Average Variance Extracted (AVE)

The average variance extracted (AVE) values concerning five constructs are displayed in the table below (

Table 4). Using AVE as a criterion in Structural Equation Modeling is an important step in determining the validity of a construct. It shows how much of the total variance is explained by the construct’s indicators. High AVE values indicate greater convergent validity.

As the AVE values vary from 0.828 to 0.918, this implies good convergent validity for all the constructs. In particular, the mitigation strategies component was also the most dominant component with the highest AVE value, equal to 0.918, indicating that a high proportion of variance was explained by its items. The environmental risk construct has an AVE value of 0.880, while governance risk follows closely with an AVE value of 0.853, both demonstrating strong convergent validity. The project performance construct has a slightly lower AVE of 0.864 but is still above the threshold of 0.50, indicating adequate validity. Finally, the AVE of social safety risk is determined to be 0.828, which also reaches an acceptable level that confirms whether the construct can explain its variance. As a whole, the AVE values indicate good convergent validity for all of the constructs, suggesting that each construct adequately explains the variance associated with its associated indicators.

4.5. Inner Model Evaluation

The evaluation of the inner structural model focuses on assessing the hypothesized relationships between the latent constructs in the proposed framework. Key criteria such as path coefficients, coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2) were examined to determine the strength and significance of the relationships. Bootstrapping procedures with 5000 resamples were employed to test the statistical significance of the path coefficients. The results offer insights into the direct and indirect effects of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks and the moderating influence of host country innovation and sustainable practices on project performance within the context of CPEC.

4.5.1. (R2) Evaluations

The R-square (R2) values of 0.965 for mitigation strategies and 0.964 for project performance indicate an exceptionally strong explanatory power of the structural model. These values suggest that 96.5% of the variance in mitigation strategies and 96.4% of the variance in project performance can be explained by the independent constructs included in the model. The minimal difference between the R-square and the adjusted R-square (both remaining at 0.965 and 0.963, respectively) further supports the robustness and stability of the model, indicating that the results are not inflated due to the inclusion of unnecessary predictors. These high R2 values highlight the effectiveness of the selected environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risk factors and host country innovation and sustainability practices in predicting project performance outcomes within the CPEC framework.

4.5.2. f-Square (f2) Analysis

The f-square (f

2) values provide insight into the effect size of each exogenous construct on the endogenous variables, supporting the interpretation of path relationships. According to Cohen’s (2020) [

13] guidelines, where 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. The results show that governance risk has a large effect (f

2 = 0.379) on mitigation strategies, while social safety risk also demonstrates a large effect (f

2 = 0.327). Moderate effects are observed from mitigation strategies on project performance (f

2 = 0.124) and environmental risk on project performance (f

2 = 0.114). In contrast, governance risk’s impact on project performance (f

2 = 0.016) and environmental risk’s effect on mitigation strategies (f

2 = 0.006) are considered weak. These findings indicate that while governance risk significantly influences the formulation of mitigation strategies, its direct effect on project performance is minimal, highlighting the mediating importance of mitigation efforts within the CPEC context.

4.5.3. Model Fit Summary

The fit summary table presented below compares the saturated and estimated models across several fit indices, including SRMR, d_ULS, d_G, Chi-square, and NFI. These indices are important for assessing the goodness of fit of the model and ensuring that the model is an adequate representation of the data (

Table 5). The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value is 0.040 for both saturated and estimated models. Since SRMR values less than 0.08 are considered indicative of a good fit, this suggests that the model provides a good representation of the data in terms of residuals.

The d_ULS (unweighted least squares discrepancy) and d_G (geodesic discrepancy) are both 0.483 and 3.026, respectively, for both models. These values indicate the discrepancy between the models and the data, and lower values generally indicate better model fit. The consistency in these values between the saturated and estimated models reflects stability in the model’s performance. The Chi-square value for both models is 6426.880, which suggests a significant fit. While a lower Chi-square value is generally preferable, this value should also be considered about the degrees of freedom and p-value. The consistency of the Chi-square across both models implies that the estimated model fits the data similarly to the saturated model. Model NFI (Normed Fit Index) was 0.794 in contexts of analysis; values slightly below this threshold can be acceptable values, and as long as the value is above 0.90, it is considered and, in general, indicative of a good fit. A value of 0.794 means that the model is moderately satisfactory; it is not a good model and requires to be improved in terms of the goodness of fit. In conclusion, the fit indices show that both the saturated and estimated models fit the data reasonably well. The SRMR and Chi-square values indicate a good model fit, while the NFI and discrepancy measures suggest that there may be room for improvement, especially in terms of achieving a more ideal fit in future model revisions.

4.6. Mediating Analysis

The diagram below is a Structural Equation Model (SEM) examining the relationships between environmental risk, social safety risk, governance risk, mitigation strategies, and project performance (

Table 6). Here, mitigation strategies are the mediating variable, with environmental risk, social safety risk, and governance risk as the independent variables and project performance as the dependent variable. According to the hypothesis, it is hypothesized that environmental risk, social safety risk, and governance risk negatively affect project performance, and the host country’s mitigation measures mediate the relationship between risk perception and project performance. The results show that environmental risk has a path coefficient of 0.259 with project performance, and the t-value of 6.768 and

p-value of 0.011 indicate that this relationship is statistically significant. This affirms the hypothesis that there exists a negative impact of environmental risk on project performance. Social safety risk has a path coefficient of 0.361, with project performance and t-value of 7.939 and

p-value of 0.005, indicating that social safety risk negatively affects project performance. Moreover, governance risk manifests a substantial effect on project performance, with a path coefficient of 0.574 and a t-value of 10.186, which validates its adverse impact on project deliverables.

The mediation findings reveal that mitigation strategies serve as a vital mediator between the various categories of risks of environmental, governance, social safety, and project performance. The risk management literature, especially within infrastructure projects, provides some theories to explain how successful mitigation may decrease the effect of risks on project outcomes. In this study, governance risk is fully mediated, indicating that strong governance structures are crucial, while environmental and social safety risks are partially mediated, suggesting active risk management can lead to better project outcomes. These results accord with sustainability theories that emphasize the need to address risks to ensure the long-term success of infrastructure projects (

Figure 3).

5. Discussions

The purpose of this research is to explore how environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks affect project performance in the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The study introduces mitigation strategies of the host country, which have been considered as the mediator variables of the model. The results indicate that each of the three dimensions of ESG risks has a significant negative impact on project performance. However, these negative effects are cushioned by the mitigation strategies of the risk reduction mechanism. The research provides new perspectives on sustainable practices towards the growing importance of efficient risk management in the undertaking of mega infrastructure projects like CPEC. Environmental risk had a significantly direct adverse impact on project performance, which was consistent with previous research results seeking to develop infrastructure construction, as well as to promote economic development and social progress, with huge environmental challenges. Infrastructure projects such as roads and dams can lead to deforestation, habitat destruction, soil erosion, air and water pollution, and the release of greenhouse gases [

90]. CPEC, as an environmental risk project, as with any large infrastructure project, is linked to numerous environmental risks. Environmental risks in the development of CPEC may involve multiple issues such as ecological impact, pollution of air and water, deforestation, and the rigorous damage caused to local ecosystems [

91]. The large path coefficient also supports the need to control environmental risks proactively to achieve the expected project outcomes. This is also supported by Hussain et al. (2024), who suggest the critical need for effective mitigation measures includes sustainable construction practices and advanced techniques to reduce ecological damage and ensure environmentally friendly development [

1]. Social risk had proportionally adverse impacts on the project performance of CPEC. The social stability and security of foreign workers are essential for project success, particularly in host countries with polarized social and political environments. The outcomes align with Rajput et al., 2022, who contend that social risks such as labor disputes, community resistance, violent protests, and security issues of foreign workers can result in delays and overrun costs on megaprojects [

4]. Governance risk depicted a significant negative impact on project performance, which highlighted the role of an accountable, efficient, and transparent governance framework in the management of CPEC as a complex project. The outcomes of this study are in line with Hussain Ejaz (2019) [

51] and Deepak Chaudhary (2023) [

92], who argue that poor governance makes the project more susceptible to risk, while good governance ensures the project’s survivability and sustainability and, thus, increases trust with stakeholders. Innovation, sustainability, and project resilience are fostered by good governance. They relate good governance to innovation and development in a positive dynamic linkage, either directly or indirectly [

51,

92].

The intermediating influence of mitigation approaches suggests that sustainable practices, innovations, and non-harmful methods are important for transforming risk issues into project development prospects. This is consistent with the findings of Olise et al. (2025) and Rajput et al. (2022), who all agree on the need for mitigation measures that must incorporate technological development and efficiency processes to enhance the project’s adaptation process and performance. The strong relationship between the risk-mitigation measures and project success highlights the importance of pre-emptive risk responses contingent upon the environmental, social, and governance setting of the country with ownership over the respondent’s project [

4,

78]. This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge that the integrated approach to risk management (environmental, social, and governance aspects combined) in CPEC with new risk mitigation tools added value concerning the performance of ventures like other mega infrastructure projects. The findings contribute to the discussion about sustainability by demonstrating empirical evidence of how integrating ESG risks into innovation-led risk management strategies can contribute to sustainable infrastructure development in an emerging market context.

6. Conclusions

This study’s conclusions highlight the significance of sustainable methods in ensuring CPEC and comparable large-scale infrastructure projects are maintained as safe endeavors. This research further proves that the utilization of pioneering technologies, along with effective, sustainable risk management strategies, can greatly address these issues and enhance project performance. More specifically, tech that protects against carbon emissions and attempts to reduce habitat disruption, combined with community engagement and strong governance policy, results in stronger performance for projects overall and better adequacy against third-party risk. This research underscores the pivotal role of tailored innovations and sustainable practices in improving risk management capabilities, ensuring that large-scale infrastructure projects can meet their objectives while promoting long-term sustainability and safety. It is advisable to formulate an adaptable policy and regulatory mechanism designed specifically for the various stages of CPEC projects to accommodate changing environmental and social circumstances. This dynamic approach will enable early course correction based on the on-ground facts, increased risk response, and more inclusive and sustainable development. CPEC projects could benefit in the long run from incorporating adaptive governance processes to ameliorate uncertainties; they allow for the possibility of radicality and facilitate a resilient and effective process for planning, implementation, and operations.

To secure long-term success for CPEC projects, policymakers must make the development and implementation of a robust ESG policy framework that includes ESG risk assessments a mandatory part of a development project. Regulatory bodies should be enhanced and provided with digital monitoring instruments for monitoring environmental and social compliance on a real-time basis. In addition, public–private partnerships should be promoted to spur innovation with R&D grants that fuel local green technologies, as well as resilient infrastructure solutions. For project managers, it is important to embed ESG risk management into the project lifecycle, from the project design through to construction and into operation. Donors need to put in place specific ESG metrics and tools like GIS and IoT for monitoring the real-time environmental impact and social contributions of their implementation. Greener purchasing behavior should be normalized, with local suppliers verified as environmental to help promote green supply chains. Project teams will need to be educated about ESG compliance and understand how to manage or mitigate any apparent risks. In addition, the design of projects integrating social value (e.g., local infrastructure development, job creation, protection of cultural heritage) can contribute to a high level of trust and resilience by stakeholders to the project. Lastly, policymakers and project implementers need to work jointly through a dedicated CPEC ESG Compliance Authority to ensure that there is accountability, transparency, and improvement in performance across the board.

There are important policy implications, particularly in high-risk geopolitical areas. The results of this study indicate that mitigation should be tailored to address different risks, e.g., environmental, governance, and social safety threats. Policymakers may need to focus on governance arrangements and risk-mitigating measures that are more consistent with local conditions to improve the performance of the project. This can contribute to the sustainability of infrastructure in conflict-ravaged areas, where efficient risk management is of keen importance for the success of the project. In the end, investing in strong mitigation will build resilience and lead to better outcomes for high-risk areas.