1. Introduction

From prolonged droughts to seasonal surges in demand, Southern Europe’s tourism-dependent regions—especially Portugal’s Algarve, which has experienced its driest year since 1931 and recorded dam reserves below 30% in some areas [

1,

2,

3]—face intensifying water stress. Tourism exerts heavy pressure on freshwater systems, with hotels being major consumers due to landscaping, pools, laundry, and guest services [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

This study asks early on: How do Algarve hotel groups adopt and communicate sustainable water reuse practices, and what factors explain differences in implementation? While technologies like on-site desalination and greywater recycling have emerged as promising solutions, their deployment across the hospitality sector remains fragmented. The Algarve provides a compelling case study due to its acute water vulnerability, economic reliance on tourism, and ongoing policy efforts to promote water efficiency.

Existing literature predominantly focuses on households or municipal systems, overlooking the organizational dynamics of tourism enterprises [

9]. Moreover, few studies examine how hospitality firms institutionalize water reuse technologies and communicate them under real-world governance constraints. Regulatory complexity, high capital costs, and reputational considerations often shape firms’ decisions—but remain underexplored in empirical research.

This article addresses these gaps by conducting a comparative qualitative case study of three Algarve hotel groups—Vila Vita Parc, Pestana Group, and Vila Galé—selected to represent varying levels of organizational capacity and technological maturity. A supplementary mini-case from Mallorca is included to contrast governance contexts and technological choices. Publicly available documents were thematically coded, grounded in organizational environmental behavior theory and OECD water governance principles [

1].

Conceptually, the study introduces the Maturity–Communication–Governance (MCG) Framework, which explains how internal resources, stakeholder signaling, and institutional alignment jointly influence sustainability transitions in the hospitality sector. Regionally, the research provides rare comparative data from Southern Europe—a context highly exposed to climate and tourism pressures. Methodologically, it applies a triangulated, document-based approach tailored to organizational analysis in data-scarce environments.

By centering hotels as strategic actors in decentralized adaptation, this study contributes to scholarship on sustainable tourism, organizational behavior, and climate governance. It also supports policy efforts aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDGs 6.4, 12.6, and 13.

The article proceeds as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature;

Section 3 outlines methodology;

Section 4 presents results;

Section 5 discusses theoretical and policy implications; and

Section 6 concludes with recommendations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

The intersection of tourism, water governance, and organizational environmental behavior has received increasing scholarly attention, particularly in regions facing water scarcity risks [

10]. However, existing research often treats these topics in isolation—focusing either on sustainable water practices, organizational behavior, governance frameworks, or critiques of technological solutions—without integrating them into a cohesive analytical perspective. This study addresses that fragmentation by proposing a synthesized approach, grounded in environmental governance theory and institutional analysis, to explain how hospitality organizations navigate water reuse under climate stress.

2.1. Sustainable Water Practices in Tourism

Hotels and resorts are major contributors to water stress due to high per-guest consumption associated with amenities such as swimming pools, landscaped gardens, and laundries [

4,

10,

11]. Many have responded by adopting efficiency technologies such as low-flow fixtures, smart irrigation, greywater reuse, and desalination [

9,

12,

13,

14]. However, the mere presence of such technologies does not ensure sustainability unless they are supported by organizational commitment and embedded in broader governance systems. Barriers such as capital intensity, fragmented regulations, and lack of technical expertise limit uptake [

15,

16].

2.2. Organizational Environmental Behavior in Hospitality

Environmental behavior within hotel firms is shaped by multiple drivers, including leadership vision, stakeholder pressure, and regulatory context [

17,

18]. Yet firms vary widely in their ability to implement sustainability. Concepts from behavioral economics, such as bounded rationality and loss aversion, help explain why hotels may adopt suboptimal or risk-averse strategies, even when more sustainable options are available [

19,

20]. Institutional theory adds a complementary lens, highlighting how coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism shape organizational responses to environmental pressures [

21]. These insights underscore that water reuse adoption is not purely a technical decision but deeply influenced by internal culture and external legitimacy expectations [

22,

23].

2.3. Governance Frameworks and Private-Sector Roles

Recent governance models—especially the OECD Principles on Water Governance—emphasize multi-level coordination, stakeholder engagement, and transparency as key to effective water management [

1,

24]. In tourism economies like the Algarve, where municipal and regional institutions often lack the capacity for large-scale infrastructure, private actors such as hotel groups can act as quasi-public entities—implementing solutions, shaping norms, and participating in governance. However, their engagement is uneven and conditioned by institutional complexity, regulatory asymmetries, and inconsistent incentive structures [

25,

26]. The broader field of environmental governance theory supports the view that sustainability outcomes depend on the interplay between agency, structure, and context [

27,

28].

2.4. Critical Perspectives on Technological Optimism

Technological approaches such as desalination and greywater recycling are often presented as win–win solutions to water stress. However, some critical literature warns against techno-optimism, noting that these systems can entail hidden environmental costs, such as energy consumption, carbon emissions, and brine discharge [

29,

30]. In addition, corporate communication often frames technology adoption in overly simplistic or celebratory terms, omitting systemic trade-offs or lifecycle impacts [

17,

31]. These critiques highlight the need for more transparent and reflexive approaches to technology-driven sustainability.

2.5. Hypotheses Development

Drawing on the literature reviewed above, this study develops three hypotheses to examine the drivers, characteristics, and challenges of water reuse implementation among hotel groups in water-scarce regions. These hypotheses aim to test how variations in organizational capacity, sustainability communication, and technological adoption stage influence water management practices in the hospitality industry.

The first hypothesis posits a positive relationship between the maturity of water reuse implementation and the organizational capacity of hotel groups. Prior research in environmental innovation suggests that firms with greater financial and technical resources are better equipped to manage initial capital expenditures, operational complexity, and regulatory uncertainties [

18,

32]. In the case of Vila Vita Parc, for example, the early adoption of a private desalination system reflects a high degree of organizational readiness and long-term environmental planning [

32,

33]. This leads to the first hypothesis:

H1. The maturity of water reuse implementation in hotel groups is positively associated with their organizational capacity and access to financial resources.

The second hypothesis concerns the relationship between sustainability performance and environmental communication. Empirical studies show that companies with more developed environmental practices tend to engage in more transparent and proactive communication strategies, often leveraging sustainability achievements as part of their branding or stakeholder engagement [

17]. In tourism, where environmental credentials can enhance reputation and customer loyalty, firms with operational water reuse systems may use communication as a strategic tool to legitimize their practices and distinguish themselves in a competitive market [

25]. Hence,

H2. Hotels with more advanced water reuse systems exhibit greater transparency and proactivity in environmental communication.

The third hypothesis addresses barriers that hinder technological adoption among hotel groups in earlier stages of implementation. Research on environmental behavior in hospitality consistently highlights structural and organizational constraints—such as high costs, technical uncertainty, and inertia in decision-making—as significant obstacles to innovation [

15,

18,

34]. These constraints are often exacerbated in firms with fewer resources or ambiguous sustainability mandates. The case of Vila Galé, currently in the feasibility phase for desalination, illustrates how such limitations may delay or complicate implementation [

35]. Therefore,

H3. Barriers to implementation—such as cost, technical complexity, or institutional inertia—are more pronounced among hotel groups at earlier stages of water reuse adoption.

These hypotheses provide the analytical foundation for comparing cases and testing how organizational and contextual factors shape the uptake and framing of water reuse technologies in the hospitality industry [

21].

2.6. Theoretical Integration and the Maturity–Communication–Governance (MCG) Framework

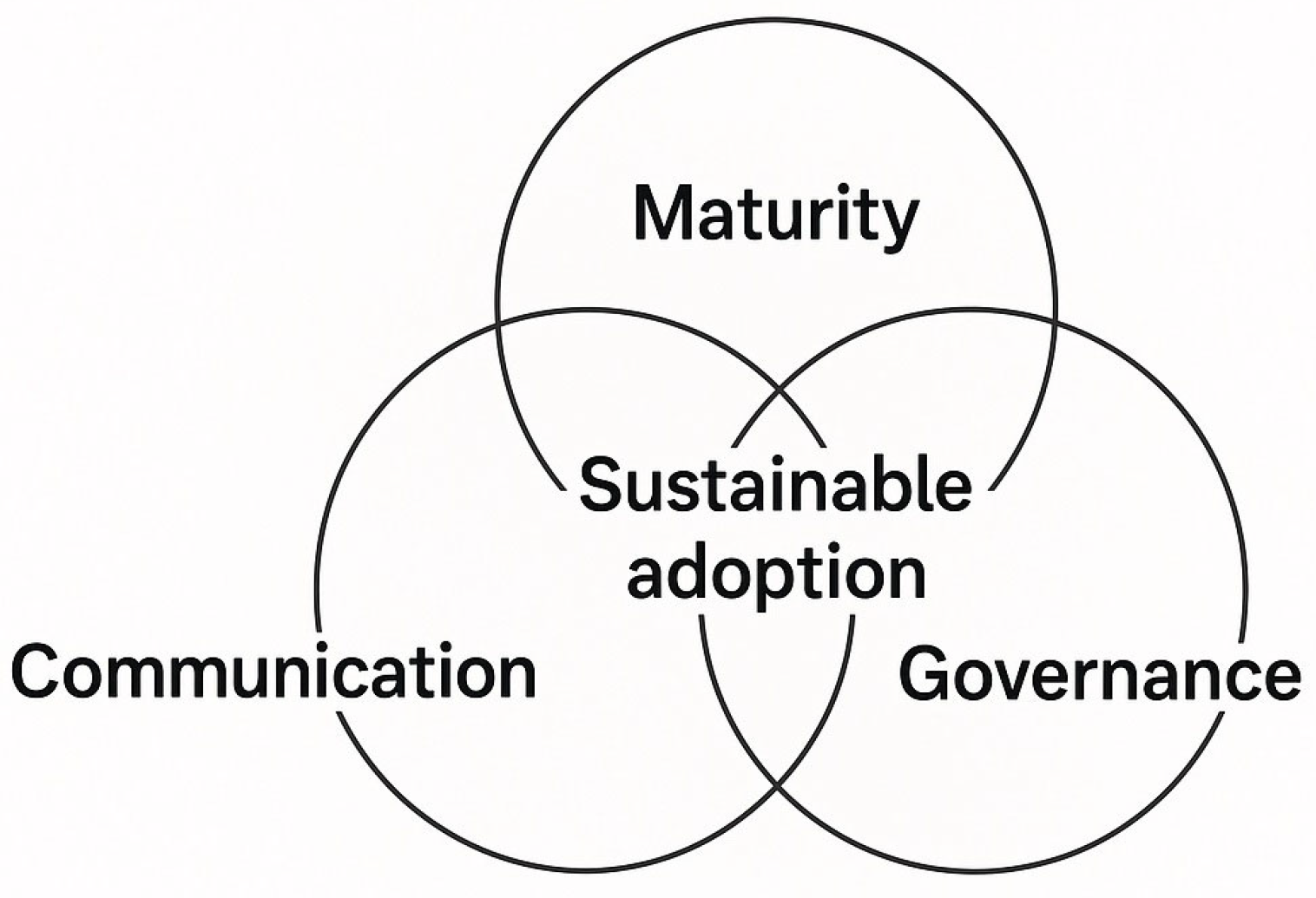

To address the fragmented perspectives reviewed in this section and fulfill the need for a more integrative theoretical foundation, this study introduces the Maturity–Communication–Governance (MCG) Framework as its central analytical model. This framework conceptualizes the adoption of sustainable water reuse technologies not as a purely technical process, but as a dynamic and iterative interaction between three dimensions:

Maturity, referring to the internal capacity, resource base, and implementation readiness of an organization to develop and operate advanced water reuse systems. It includes both financial and managerial elements as identified in innovation adoption and organizational behavior literature [

18,

32].

Communication, defined as the visibility, framing, and credibility of environmental practices communicated to stakeholders through reporting, branding, or engagement. It captures how sustainability is signaled, negotiated, and legitimized in both market and governance environments [

17,

25].

Governance, representing the alignment between organizational practices and institutional frameworks at local, regional, and national levels. Drawing on the OECD Principles on Water Governance [

1] and adaptive governance theory [

28,

36], this dimension assesses whether sustainability efforts are supported, constrained, or shaped by broader policy environments.

The MCG Framework is informed by institutional theory—particularly DiMaggio and Powell’s (1983) work on isomorphism—as well as environmental governance scholarship that emphasizes multi-scalar coordination and adaptive capacity [

21,

36]. Together, these perspectives highlight how firms respond not only to market signals but also to regulatory expectations and reputational pressures.

Rather than isolating technological, organizational, or policy variables, the MCG model emphasizes their interdependence. For example, organizational maturity can reinforce communicative confidence, which in turn can attract policy partnerships or regulatory support—creating a positive feedback loop. Conversely, firms with low maturity may avoid public communication, weakening their governance alignment and slowing sustainability transitions.

This framework is particularly suited to contexts like Southern Europe’s tourism sector, where climate vulnerability, policy fragmentation, and uneven organizational capacities co-exist. As such, the MCG model functions both as a conceptual synthesis and as a diagnostic tool for identifying where sustainability pathways succeed, stall, or risk becoming symbolic rather than transformative.

The next section applies this framework to empirical cases in Portugal and Spain, enabling a comparative analysis of how hotels adopt, communicate, and institutionalize water reuse strategies.

3. Data and Methods

This study employed a comparative case study design [

37,

38] to investigate water reuse practices in hospitality settings, with a focus on hotel groups operating in the Algarve—a Mediterranean region marked by increasing water scarcity. The approach combined qualitative document analysis with thematic coding [

39] and discourse analysis [

40], aiming to understand how organizational capacity, environmental communication, and governance engagement shaped sustainability outcomes in the tourism sector. The design was informed by the OECD Water Governance Principles [

1] and theoretical perspectives from organizational environmental behaviour, including behavioral economics and institutional theory [

41].

To capture variation in sustainability engagement and implementation, the case selection followed a purposive sampling strategy based on three dimensions: technological maturity, organizational capacity, and communicative transparency.

Three hotel groups were selected based on their regional representativeness, level of environmental engagement, and availability of publicly accessible data. All three operated in the Algarve, a region experiencing acute water stress and intense tourism-driven demand, making them relevant cases for studying adaptive water strategies. Each group had demonstrated some degree of environmental commitment, either through documented investment in water reuse technologies or public declarations of sustainability efforts. Furthermore, all had a substantial presence in the public domain, with available materials such as sustainability reports, press coverage, and technical documentation, ensuring the feasibility of systematic and transparent analysis.

Accordingly, the following cases were included:

- -

Vila Vita Parc, located in Porches, represented a technologically mature case, having operated a desalination system since 2015, which supplied approximately 70% of its water needs [

33].

- -

Pestana Hotel Group was selected due to its recent, multi-unit deployment of desalination infrastructure across six Algarve hotels in 2023, with a combined treatment capacity of 960 m

3/day [

42,

43].

- -

Vila Galé Hotels, with properties in Lagos, Vilamoura, and Tavira, was chosen as a feasibility-phase case, currently conducting studies for potential non-potable water reuse through desalination [

35].

To strengthen the comparative dimension of the analysis, an organizational profile table was developed to summarize key characteristics of the hotel groups, including number of units, market segment, estimated revenue, and level of sustainability investment.

This typological summary supported the comparative design logic of the study. By highlighting variation in organizational scale, revenue base, and environmental investment,

Table 1 illustrates the structural conditions under which each hotel group approached water reuse. Vila Vita Parc, despite its small size, exemplified an early-adopter profile, likely driven by strategic branding and environmental positioning. Pestana Group represented a scaling case, where greater financial capacity enabled broader implementation. Vila Galé, with intermediate resources, remained cautious—consistent with its mid-market positioning. These contrasts justified their selection as divergent implementation cases, enabling an analysis of how internal capacity influenced sustainability transitions.

To enhance cross-contextual validity and assess the broader relevance of the findings, a comparative mini-case from Mallorca, Spain, was integrated into the analysis. The resort, identified through secondary sources, employed a greywater recycling system for landscaping and toilet flushing, rather than desalination [

10]. The objectives are to contrast technological approaches to water reuse—specifically desalination versus greywater recycling—to highlight institutional and regulatory differences between the Portuguese and Spanish Mediterranean contexts, and to assess the applicability of the proposed Maturity–Communication–Governance (MCG) framework beyond the Algarve. This strategic inclusion broadened the analytical scope, enabling the identification of contextual drivers and constraints that shaped sustainability strategies in tourism under similar climatic pressures but different policy environments [

44,

45].

3.1. Data Collection

Data were drawn exclusively from publicly accessible documents, defined as materials that did not require proprietary access, passwords, or direct corporate collaboration. These included the following: Official websites of the hotel groups; Sustainability and environmental performance reports; Technical fact sheets describing water reuse systems; Press releases and interviews; Media articles from sectoral and national outlets (e.g., Publituris Hotelaria, Expresso, ADENE); Policy frameworks (e.g., Compromisso pela Eficiência Hídrica do Algarve); Feasibility reports (e.g., Vila Galé studies); Selected guest reviews (e.g., TripAdvisor), used for exploratory purposes. Documents were included if they (1) pertained to water-related sustainability practices; (2) were published between 2015 and 2024; and (3) originated from a credible source. An exploratory scan of user-generated content, particularly on TripAdvisor, was conducted to evaluate whether and how guests perceived water-related sustainability practices. While this material was not systematically coded, it offered supplementary insights into the visibility and reception of environmental efforts by consumers [

46].

3.2. Methodological Approach

The analytical process comprised three interconnected components:

Thematic Coding: Documents were coded across five dimensions—technological infrastructure, environmental communication, scale of intervention, efficiency outcomes, and stakeholder engagement. Coding categories were tested on a subset of data and refined for consistency. A second researcher reviewed a random sample to enhance inter-coder reliability [

39].

Discourse Analysis: The study analyzed rhetorical strategies used by hotels to frame environmental legitimacy. Key terms such as “eco-conscious luxury” and “climate adaptation” were traced across communication channels to reveal tensions between branding and actual sustainability commitments [

33].

Cross-Case Comparison: A comparative matrix was developed to synthesize data on implementation stage, technology type, communication strategy, and barriers. This matrix supported a structured, cross-contextual comparison across the Algarve cases and the Mallorca resort [

15].

To ensure methodological rigor, the study employed triangulation across various document types (corporate, media, institutional), applied systematic coding protocols with inter-coder review, and aligned its analysis with the MCG theoretical framework to guide interpretation and minimize researcher bias.

3.3. Limitations

Despite efforts to ensure analytical rigor, the methodology faced several limitations, including selection bias due to the focus on firms with visible environmental communication, which may have excluded less transparent or less active organizations; source bias stemming from reliance on public-facing materials that may reflect curated corporate narratives rather than operational realities; and interpretive bias, as researcher subjectivity cannot be fully eliminated despite verified coding consistency. Additionally, the study’s limited generalizability—owing to a non-random sample of only four cases in Southern Europe—means that findings are analytically transferable but not statistically generalizable. Future research should incorporate primary data, such as interviews with sustainability managers, site visits, or internal audits, to gain deeper insight into informal decision-making and implementation dynamics. A more systematic analysis of third-party certifications and consumer feedback could also enhance understanding of external perceptions and organizational legitimacy.

4. Results

This section presents the findings from the comparative analysis of three hotel groups in the Algarve—Vila Vita Parc, Pestana Hotel Group, and Vila Galé Hotels—and includes a mini-case from Mallorca, Spain. The analysis is structured around the three previously stated hypotheses.

4.1. Organizational Capacity and Maturity of Water Reuse Implementation

The implementation of water reuse technologies in the hospitality sector appears to reflect varying levels of organizational capacity and maturity across hotel groups, as outlined in

Table 2.

Interpretation of sustainability reports and public materials suggests that the depth of implementation may be shaped by each group’s strategic orientation, financial capacity, and risk tolerance. Vila Vita Parc, a luxury resort with established environmental goals, has operated an on-site desalination system since 2015, reportedly supplying about 70% of its water needs [

33]. This move aligns with its eco-branding strategy and can be read as a case of normative isomorphism [

21]. Pestana Hotel Group implemented desalination in six Algarve locations in 2023, highlighting a scaling strategy supported by its organizational size and access to regional efficiency initiatives [

42,

43]. Vila Galé Hotels remains in the feasibility phase, citing financial and regulatory uncertainties—framing its cautious approach as rational under bounded decision-making conditions [

35]. Despite the presentation of desalination as an environmentally responsible innovation, sustainability reports largely omit discussion of its negative externalities, such as high energy demand and brine discharge. Reverse osmosis systems, according to the literature, consume between 3 and 5 kWh per m

3 of freshwater, potentially resulting in 1.5–2.5 kg of CO

2 emissions per m

3 when powered by fossil-based electricity [

9,

42]. Additionally, none of the hotel groups acknowledge brine management practices, despite known ecological risks to marine ecosystems [

20]. This selective framing suggests a strategic omission of potentially controversial environmental impacts, revealing a tension between sustainability branding and operational reality. In contrast, the Mallorca mini-case illustrates an alternative model of water reuse via greywater recycling, which avoids many of desalination’s externalities but introduces other logistical challenges.

4.2. Environmental Communication and Transparency

Variations in environmental communication strategies across hotel groups appear to be influenced by both technological maturity and reputational considerations (

Table 3).

Discourse analysis reveals that Vila Vita Parc constructs a strong sustainability narrative, integrating desalination into its core brand identity through visually compelling media and press releases [

33]. Pestana Group communicates more selectively, focusing on institutional channels and aligning its discourse with regulatory expectations [

42,

43]. Vila Galé’s sparse communication, limited to occasional media references, suggests reputational caution in light of its early-stage implementation and perceived risks [

35].

4.3. Barriers to Implementation at Early Adoption Stages

Barriers encountered by the hotel groups vary in nature and intensity, as outlined in

Table 4.

Among the cases, Vila Galé reported the most pronounced barriers, especially related to financial feasibility, regulatory ambiguity, and technical complexity [

35]. These barriers are often publicly acknowledged in corporate interviews, reinforcing a narrative of rational caution in an uncertain environment. Pestana Group faced challenges coordinating across sites but benefited from prior institutional learning and participation in regional programs. Vila Vita Parc’s early investment and operational autonomy appear to have minimized its barriers, though internal project stabilization may have required unreported effort [

33].

4.4. Comparison with Non-Algarve Case: Mallorca Mini-Case

The Jumeirah Port Soller Hotel & Spa in Mallorca offers a useful contrast by employing greywater recycling instead of desalination. The technology was selected due to regulatory constraints on brine discharge and higher local energy costs—conditions that discouraged desalination [

10,

34]. While the resort’s communication is modest and compliance-oriented, its choice of technology reflects a policy-driven model of adaptation, shaped more by external constraints than branding aspirations. Participation in EU and local incentive schemes also facilitated implementation, a dynamic that mirrors the Pestana Group’s case [

42,

44].

4.5. Comparative Table and Timeline

To synthesize findings across the four cases,

Table 5 summarizes key dimensions of implementation, communication, and barriers.

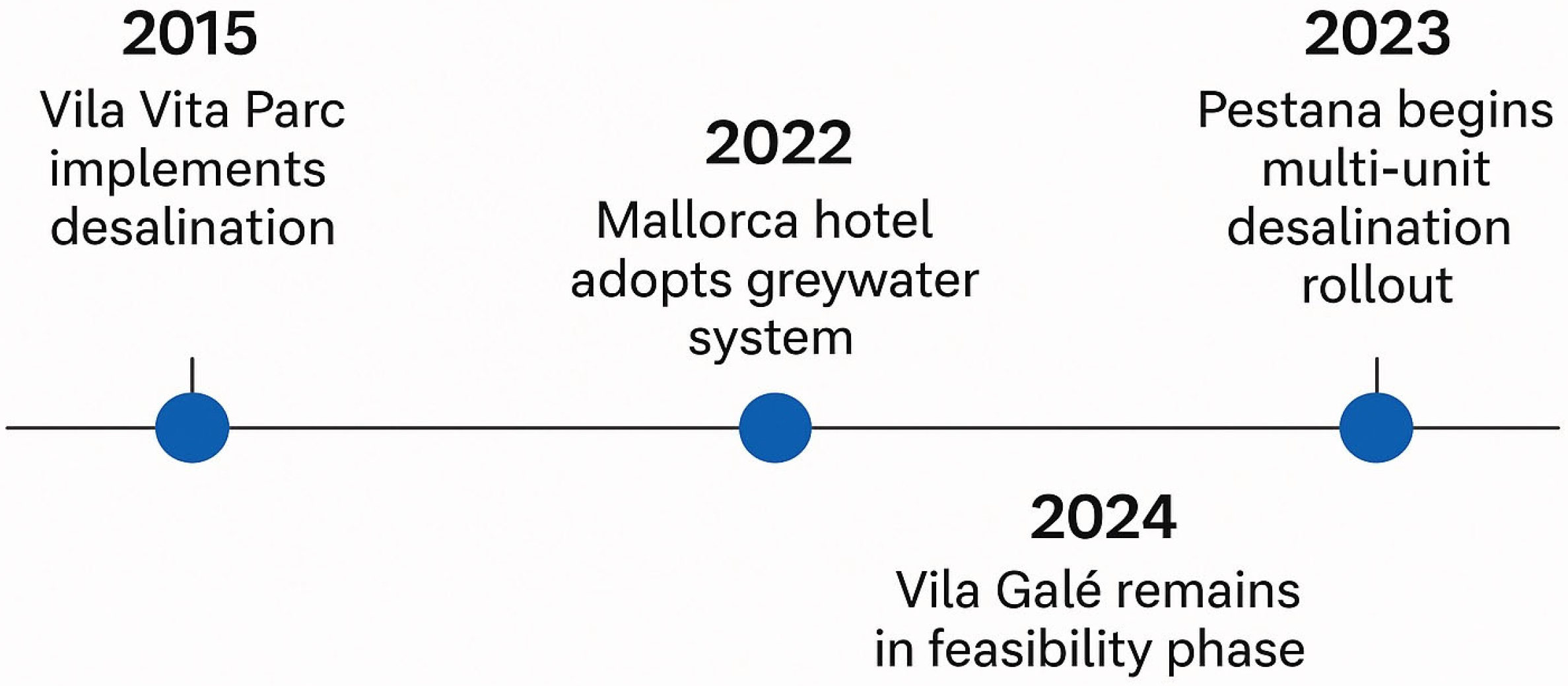

Figure 1 presents a visual timeline of water reuse adoption across cases, highlighting asynchronous implementation shaped by internal capacities and external policy environments.

These findings support the three working hypotheses: (1) the maturity of water reuse implementation appears positively associated with organizational and financial capacity; (2) transparency in environmental communication increases with technological advancement and reputational interest; and (3) early-stage adopters face more significant barriers, both perceived and actual. The Mallorca mini-case further illustrates how context-specific policy and pricing conditions shape technological pathways, emphasizing the need for locally tailored sustainability strategies in Mediterranean tourism sectors.

5. Discussion

This study’s comparative analysis of three Algarve hotel groups—Vila Vita Parc, Pestana Group, and Vila Galé—along with a mini-case from Mallorca, offers nuanced insights into how organizational maturity, communication strategies, and governance alignment interact to shape water reuse adoption in tourism. These findings extend current understanding of organizational environmental behavior, institutional dynamics, and the challenges of pro-environmental transitions in high-consumption sectors.

5.1. Organizational Capacity as a Critical Enabler

Our results confirm and extend prior research showing that organizational capacity—financial strength, operational scale, and strategic vision—is fundamental to advancing water reuse technologies [

9,

12,

18]. Vila Vita Parc exemplifies the enabling role of early capital investment and autonomy, consistent with findings on innovation adoption in hospitality [

18,

21]. Pestana’s multi-site strategy illustrates the benefits of institutional maturity and cross-unit learning, aligning with concepts of organizational isomorphism in sustainability scaling [

32,

45]. Vila Galé’s stalled progress underscores bounded rationality and institutional inertia [

21,

46], echoing constraints reported for resource-limited firms [

46].

Together, these cases highlight how differential capacities shape adaptive responses to environmental stress, emphasizing practical implications for firms to build financial and organizational strength to successfully implement water reuse technologies.

5.2. Transparency and Environmental Communication

The clear link between technological maturity and communication proactivity aligns with institutional theory frameworks, notably normative and mimetic isomorphism [

17,

45]. Vila Vita Parc’s eco-branding exemplifies sustainability communication as a form of environmental signaling, an idea supported by research arguing that transparency builds legitimacy and stakeholder trust [

17]. Pestana’s more subdued institutional framing contrasts with Vila Galé’s near silence, reflecting varying reputational incentives and risk management strategies [

44,

46]. This gradient adds empirical depth to the understanding that communication is not only marketing but a strategic component in environmental governance and legitimacy construction.

However, this strategic use of sustainability messaging raises concerns about greenwashing, particularly when public-facing narratives omit critical environmental trade-offs or exaggerate ecological benefits. For instance, Vila Vita Parc frequently employs terms like “eco-conscious luxury” and “sustainable gardens powered by desalination” in its promotional materials [

33], yet no lifecycle environmental assessments or performance metrics (e.g., CO

2 emissions, brine volume, energy sources) are disclosed alongside these claims. This absence of accountability mechanisms weakens the credibility of such communication, especially in contexts where environmental legitimacy functions as a market differentiator.

To address this, the tourism and hospitality sector increasingly engages with international frameworks of environmental accountability, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), ISO 14001 [

49,

50], and sector-specific ecolabels (e.g., Travelife, Green Key). These standards encourage firms to publish quantitative indicators of water efficiency, energy use, emissions, and resource impact. Yet, none of the hotel groups examined in this study fully adhere to these frameworks in their communication of water reuse initiatives—an omission that risks eroding stakeholder trust and undermining progress toward genuine sustainability. These findings contribute to broader theoretical debates on organizational isomorphism and governance by illustrating how external pressures shape, but do not fully determine, communication practices.

5.3. Barriers and Institutional Inertia

Consistent with H3 and the prior literature [

4,

15,

34], early adopters face persistent obstacles: high costs, regulatory ambiguity, and infrastructural complexity. Vila Galé’s public acknowledgment of these challenges exemplifies the ‘wait and see’ behavior described in institutional theory [

21,

46]. Pestana and Vila Vita’s alignment with regional programs confirms how coercive pressures and governance frameworks can mitigate barriers, echoing findings on policy-driven facilitation of environmental innovation in tourism [

37]. This underscores the practical importance of integrated governance to support lagging actors and the theoretical relevance of institutional inertia in shaping sustainability transitions.

5.4. The Maturity–Communication–Governance (MCG) Framework

Synthesizing these insights, the MCG Framework (

Figure 2) conceptualizes water reuse adoption as the dynamic interplay among organizational maturity, communication transparency, and governance alignment.

These dimensions reinforce each other. For example, Vila Vita Parc illustrates the full synergy of the MCG model: it combines mature infrastructure (desalination system operating since 2015), strong environmental messaging (featured prominently in sustainability reports and branding), and active engagement with regional water governance initiatives [

14,

42]. This creates a reinforcing feedback loop where internal capability, public legitimacy, and institutional alignment drive further investment and leadership in sustainability [

11,

12].

Conversely, firms lacking one or more of these dimensions—such as Vila Galé—struggle to initiate or sustain water reuse transitions [

48]. The MCG model therefore extends prior theoretical approaches by explicitly linking infrastructural, discursive, and institutional drivers of organizational adaptation, offering a transferable tool for analyzing other resource-intensive sectors and contributing to governance scholarship.

5.5. Rethinking Technological Optimism

While desalination is widely promoted as a remedy for water scarcity, our findings reveal selective sustainability framing that omits key environmental costs such as energy intensity and brine disposal [

29]. Vila Vita Parc, while publicly emphasizing its environmental leadership, does not disclose these impacts in its promotional materials—highlighting the tension between environmental branding and ecological transparency [

17]. This pattern reflects broader critiques of techno-optimism, where high-profile solutions are deployed without full lifecycle accountability or discussion of trade-offs [

29,

51]. Moreover, such selective disclosure can obscure public understanding and hinder policy dialogue. For instance, Vila Vita’s corporate communications celebrate “climate resilience through innovation,” yet omit lifecycle assessments or mitigation strategies for the system’s carbon footprint [

33].

This selective emphasis on benefits while omitting costs exemplifies what scholars describe as “narrative asymmetry” in corporate sustainability communication—a strategy that aligns with branding logic but diverges from principles of scientific integrity and transparent governance. Embedding sustainability claims within frameworks like GRI’s Water and Energy Disclosures (GRI 303 and 302) [

49,

52] or ISO 14001 environmental management systems would compel firms to report both efficiencies and externalities, providing a more balanced and verifiable account of impact. As the tourism sector increasingly faces regulatory scrutiny and rising expectations from environmentally conscious consumers, overlooking such dimensions may backfire reputationally. In this sense, critical scrutiny of techno-optimistic narratives is not just ethically necessary—it is strategically prudent for firms seeking long-term legitimacy in sustainability markets.

5.6. Practical Contributions and Global Relevance

Although the study focuses on large hotel groups, its insights apply directly to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which often face even greater financial, technical, and regulatory constraints. Vila Galé’s cautious approach reveals the systemic barriers that less-resourced firms must navigate [

46]. For such actors, incremental strategies—like rainwater harvesting or shared infrastructure—may be more viable entry points into sustainability transitions. These findings support calls for tiered policy instruments that provide differentiated incentives and technical support based on firm size and capacity [

47,

48].

At the same time, this research aligns with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It advances SDG 6.4 (efficient water use) and SDG 12.6 (corporate sustainability reporting) by demonstrating how private actors can meaningfully contribute to decentralized water governance [

53]. It also reinforces SDG 13 (Climate Action) by showcasing how local adaptation strategies, when aligned with governance frameworks, can support broader environmental resilience [

36]. By integrating practical and global dimensions, this section underscores that organizational sustainability is both a policy challenge and a governance opportunity, particularly in sectors where consumption intensity meets climate vulnerability.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed how major hotel groups in Portugal’s Algarve, supported by a comparative case in Mallorca, adopt and communicate sustainable water reuse amid growing water stress intensified by tourism and climate change. The comparative analysis identified three key drivers influencing adoption: organizational maturity, transparency in environmental communication, and alignment with governance frameworks. While groups like Vila Vita Parc and Pestana illustrate advanced, well-integrated approaches to water reuse, Vila Galé’s case underscores persistent barriers such as financial limitations, regulatory complexity, and institutional inertia—especially relevant for early adopters and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These findings demonstrate that voluntary initiatives alone are insufficient. Advancing water resilience in the tourism sector requires deliberate governance strategies that incentivize infrastructure investment, reduce regulatory friction, and enable broader participation.

6.1. Key Contributions and Policy Pathways

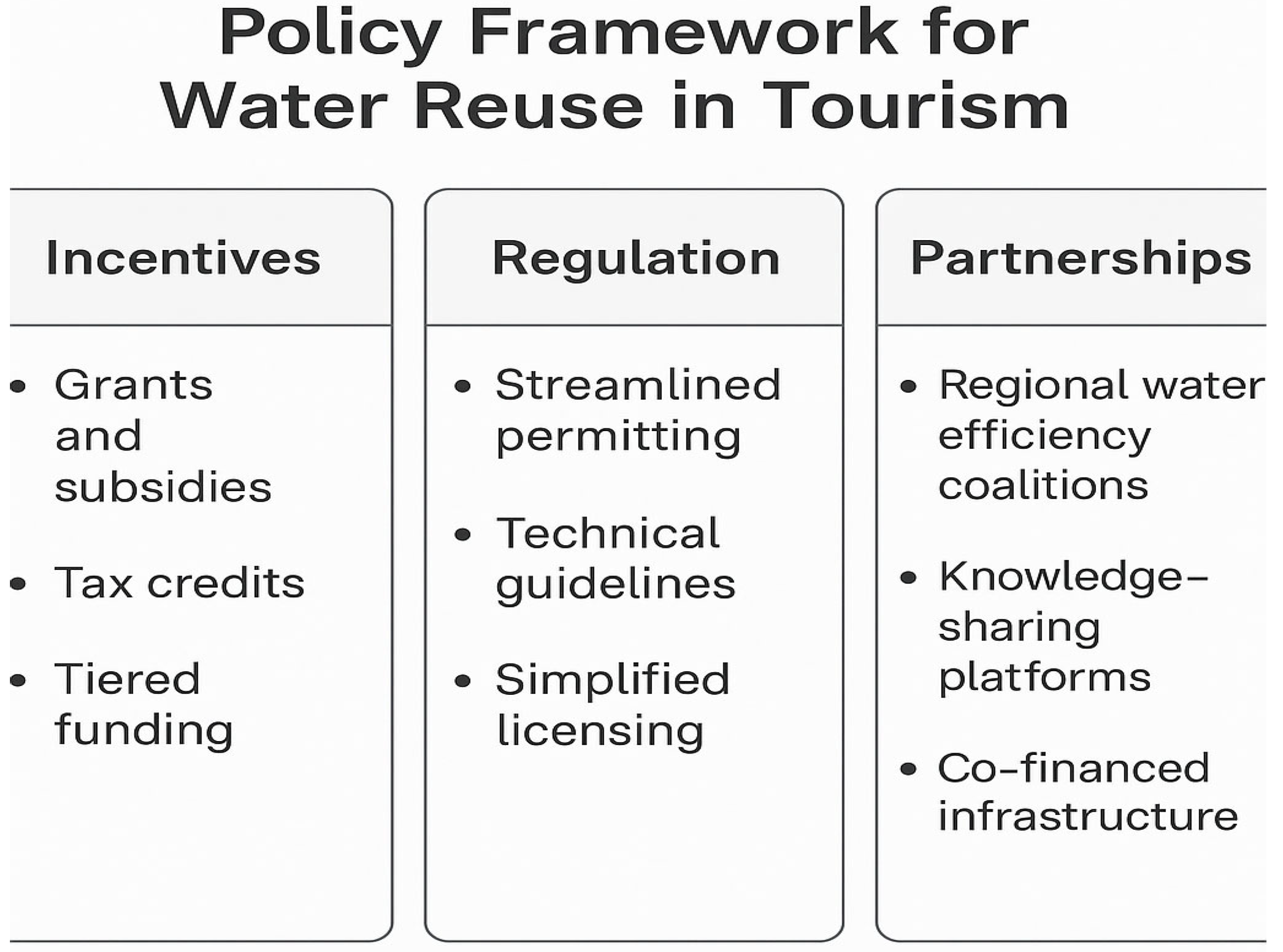

Drawing on insights from the case studies and grounded in water governance principles, this study proposes an integrated policy framework for advancing water reuse in tourism. The framework rests on three interconnected levers:

Financial Incentives—including targeted grants, tax credits for efficiency benchmarks, and tiered funding mechanisms to support SMEs and first movers.

Regulatory Simplification—through streamlined permitting processes, standardized technical criteria, and more accessible licensing paths for decentralized systems such as small-scale desalination or greywater reuse.

Public-Private Partnerships—fostering shared infrastructure models, destination-wide water efficiency commitments, and cross-operator knowledge exchange.

These levers are illustrated in

Figure 3, outlining strategic pathways enabling tourism enterprises—regardless of size—to participate meaningfully in water resilience transitions.

This research contributes to four domains:

Theoretically, by introducing the Maturity–Communication–Governance (MCG) Framework as a transferable model to analyze how infrastructure, communication, and policy alignment reinforce one another in sustainability transitions.

Empirically, by offering rare comparative data on water reuse in commercial tourism infrastructure in Southern Europe.

Critically, by highlighting the risks of selective disclosure in environmental communication, particularly around high-cost, high-impact technologies such as desalination.

Practically, by providing a roadmap emphasizing how SMEs can be integrated more equitably into sustainability transitions through scaled support.

Moreover, the MCG Framework holds promise beyond the hospitality sector. Its core logic—linking internal readiness, external signaling, and policy engagement—can be adapted to other resource-intensive contexts such as irrigated agriculture, aquatic and leisure parks, or resorts in arid regions beyond Europe, where environmental pressures demand coordinated sustainability responses.

6.2. Alignment with Global Sustainability Goals

The study supports multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 6.4 on efficient water use, SDG 12.6 on corporate sustainability reporting, and indirectly SDG 13 on climate action, by emphasizing decentralized adaptation and positioning private-sector actors as key partners in environmental governance.

6.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While this study offers valuable comparative insights, it is limited by its reliance on secondary data and the focus on large hotel groups in specific Mediterranean regions. Future research should incorporate primary data collection, including interviews with hotel managers, engineers, and policymakers, to capture internal decision-making processes and informal dynamics. Examining guest perceptions could provide valuable insights into how water reuse initiatives are received and trusted by users.

Expanding the comparative scope to other water-scarce regions—such as Morocco, Tunisia, or California—would test the transferability of the MCG Framework across diverse governance systems, economic contexts, and cultural settings. Further studies might also explore other hotel categories, including budget or boutique hotels, to better understand barriers and enablers across the sector.

To sum up, sustainable water reuse in tourism—and beyond—depends not only on technology availability, but on a robust interplay of organizational capacity, strategic communication, and institutional support. By identifying these drivers and proposing actionable pathways, this study lays the groundwork for advancing inclusive and effective water governance in sectors facing increasing environmental stress.