Cultural Ecosystem Services of Grassland Communities: A Case Study of Lubelskie Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How are grassland communities perceived by respondents in terms of their capacity to provide cultural ecosystem services? Which types of services are most characteristic of these ecosystems?

- Does the field of study (professional background) and place of residence influence respondents’ perception of ecosystem services provided by different types of grassland communities?

- Which forms of grassland communities are perceived by respondents from different study fields as the most attractive for recreation and leisure, and which are associated with the aesthetics of the surroundings?

- What natural and landscape features are considered most important in the context of recreation, leisure, and aesthetic value of the environment?

- Are there significant differences in the declared monetary values (WTP—willingness to pay/WTA—willingness to accept) for different forms of grassland communities depending on the field of study and place of residence?

- Which type of grassland community has the highest cultural ecosystem service valuation per area unit in the Lublin Voivodeship?

- –

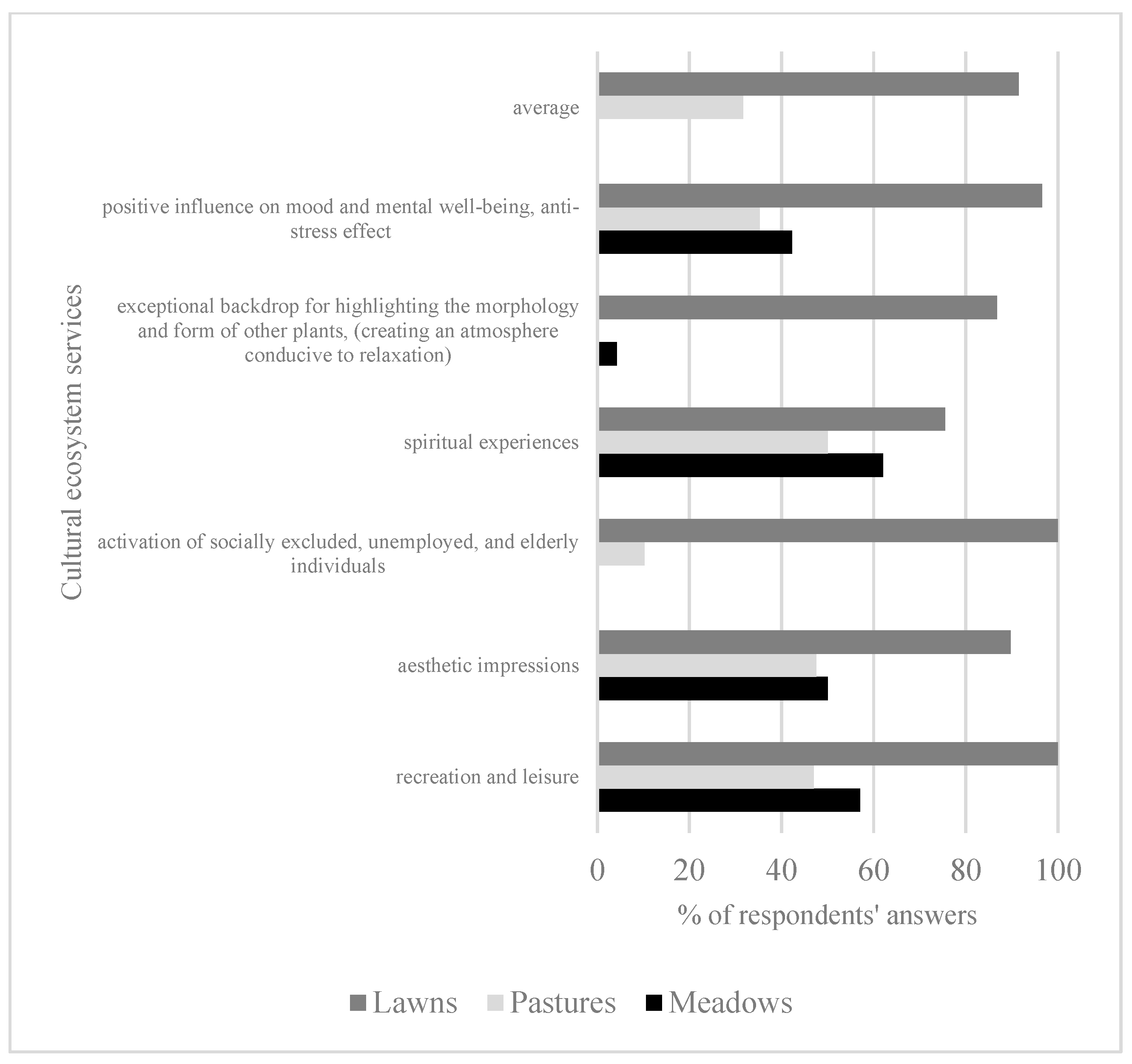

- H1: Respondents perceive grassland communities as an important source of cultural ecosystem services, with the most frequently indicated being recreational and leisure benefits, aesthetic values, community engagement, serving as a background for other plants, and spiritual experiences.

- –

- H2: The perception of ecosystem services provided by different forms of grassland communities is significantly influenced by the respondent’s field of study and place of residence.

- –

- H3: According to respondents (regardless of field of study), lawns are perceived as the most attractive for recreation and leisure, while meadows are considered most beneficial in terms of improving the aesthetics of the surroundings.

- –

- H4: Air quality, tranquillity, and oxygen production are perceived as the most important natural features of selected grassland communities for recreation and leisure, while scenic landscapes and greenery of the surroundings are seen as key elements of aesthetic value.

- –

- H5: There are statistically significant differences in declared WTP and WTA amounts among students of different fields of study for the same grassland communities.

- –

- H6: Meadows have the highest total valuation of cultural ecosystem services (WTP + WTA) per unit area in the Lublin Voivodeship.

2. Materials and Methods

- The ecological and economic importance of different GC land-use forms;

- The functions and ecosystem services provided by GC;

- The natural and scenic values of GC important for cultural services in recreation and leisure;

- The aesthetic contribution of GC to the surrounding landscape;

- 5.

- Respondents’ willingness to pay for benefits provided by GC;

- 6.

- The compensation they would expect for the reduction or loss of such benefits, were analysed using the contingent valuation method [21].

- –

- Air quality (cleanliness, scent);

- –

- High air humidity;

- –

- Temperature regulation of soil and air;

- –

- Oxygen production and CO2 absorption;

- –

- Air sterilisation properties;

- –

- Improvement of surface water quality and availability;

- –

- Silence and tranquillity;

- –

- Rich flora and fauna;

- –

- Terrain relief, openness, sunlight, and shaded areas.

- –

- Scenic beauty;

- –

- Proximity to water bodies;

- –

- Green-dominant surroundings;

- –

- Varied terrain relief;

- –

- Expansive flatlands;

- –

- Mixed land-uses;

- –

- Presence of water reservoirs;

- –

- Traditional usage (grazing animals, haystacks);

- –

- Modern usage (baled hay);

- –

- Floral diversity (blooming plants);

- –

- Wetlands (river valleys, swamps, peat bogs).

3. Results

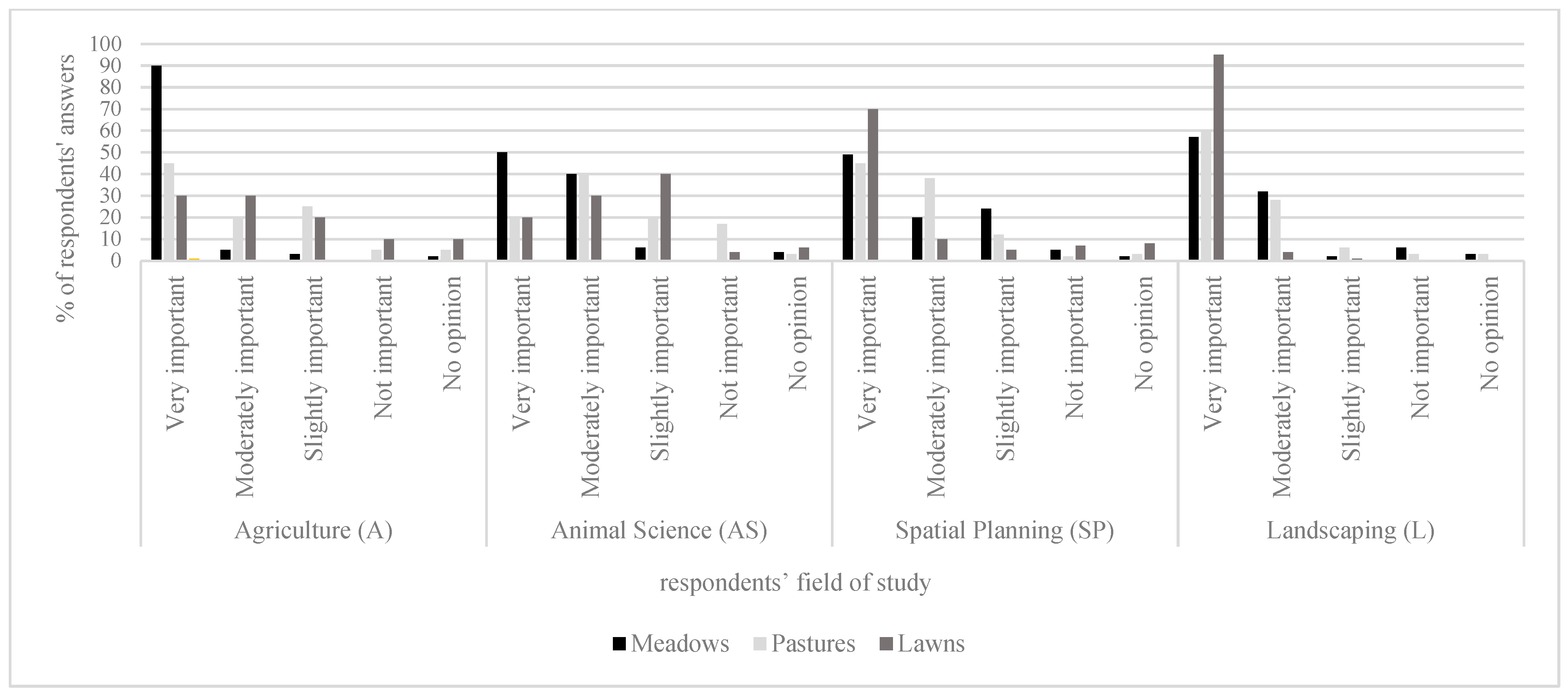

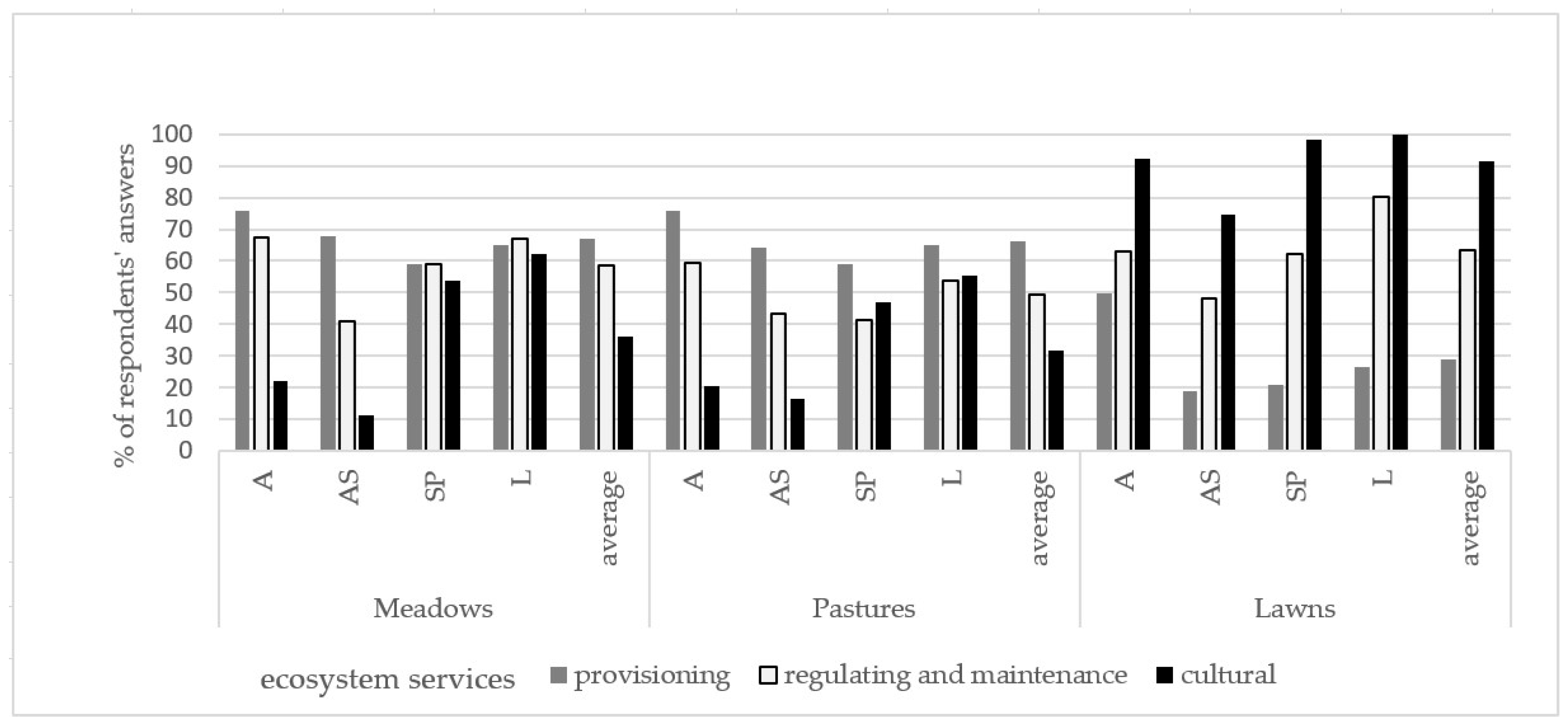

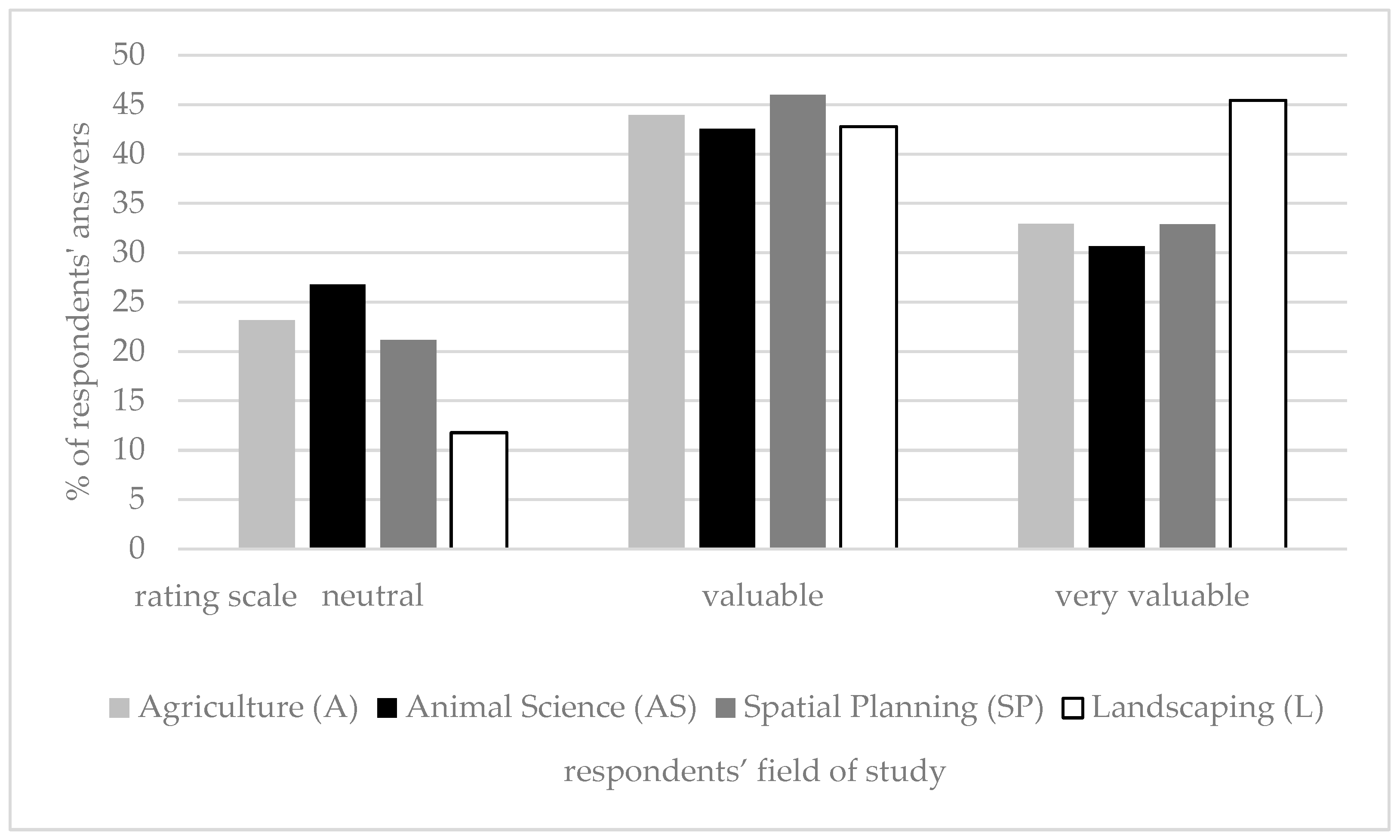

3.1. Evaluation of Recreational and Leisure Attractiveness

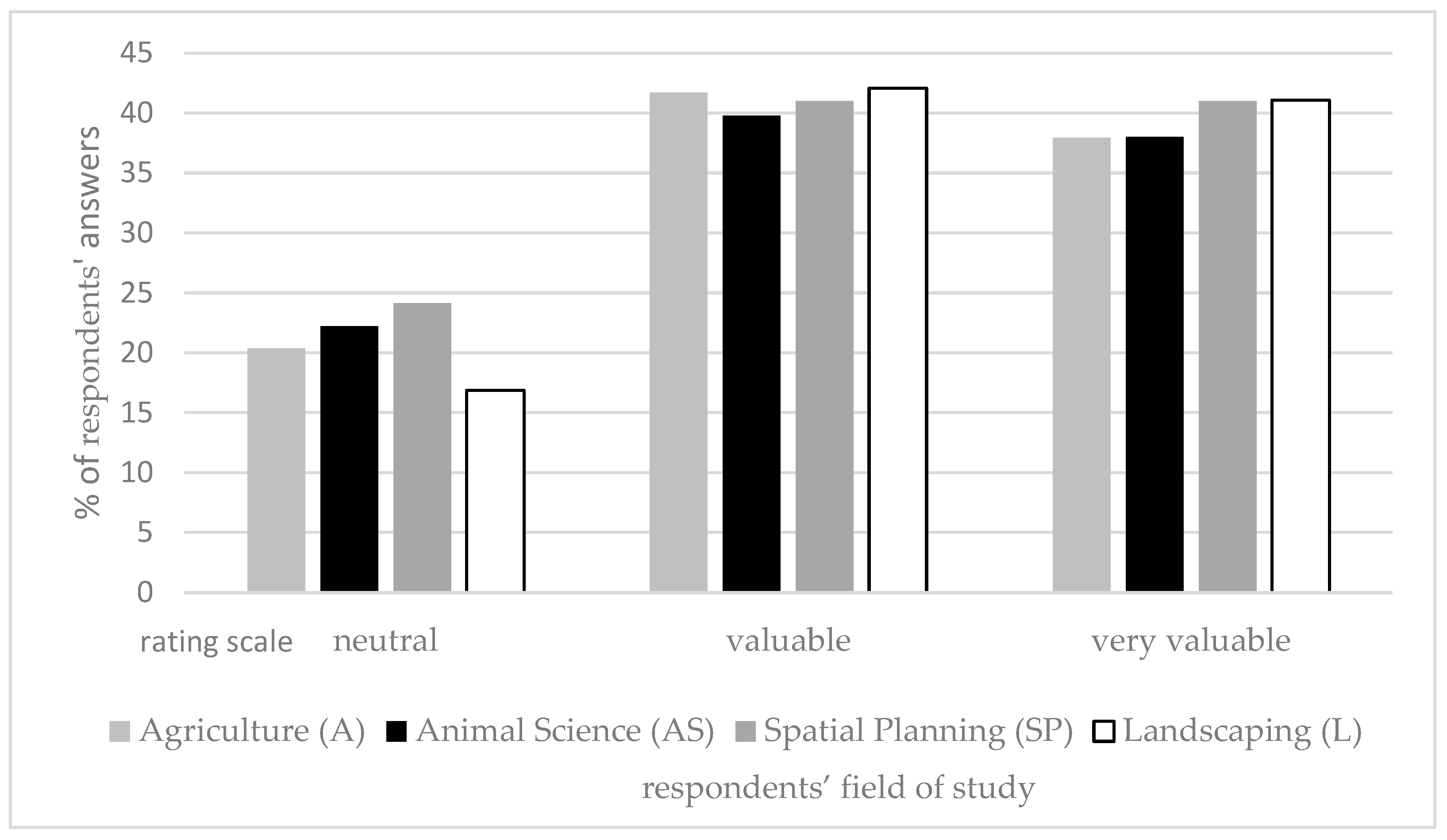

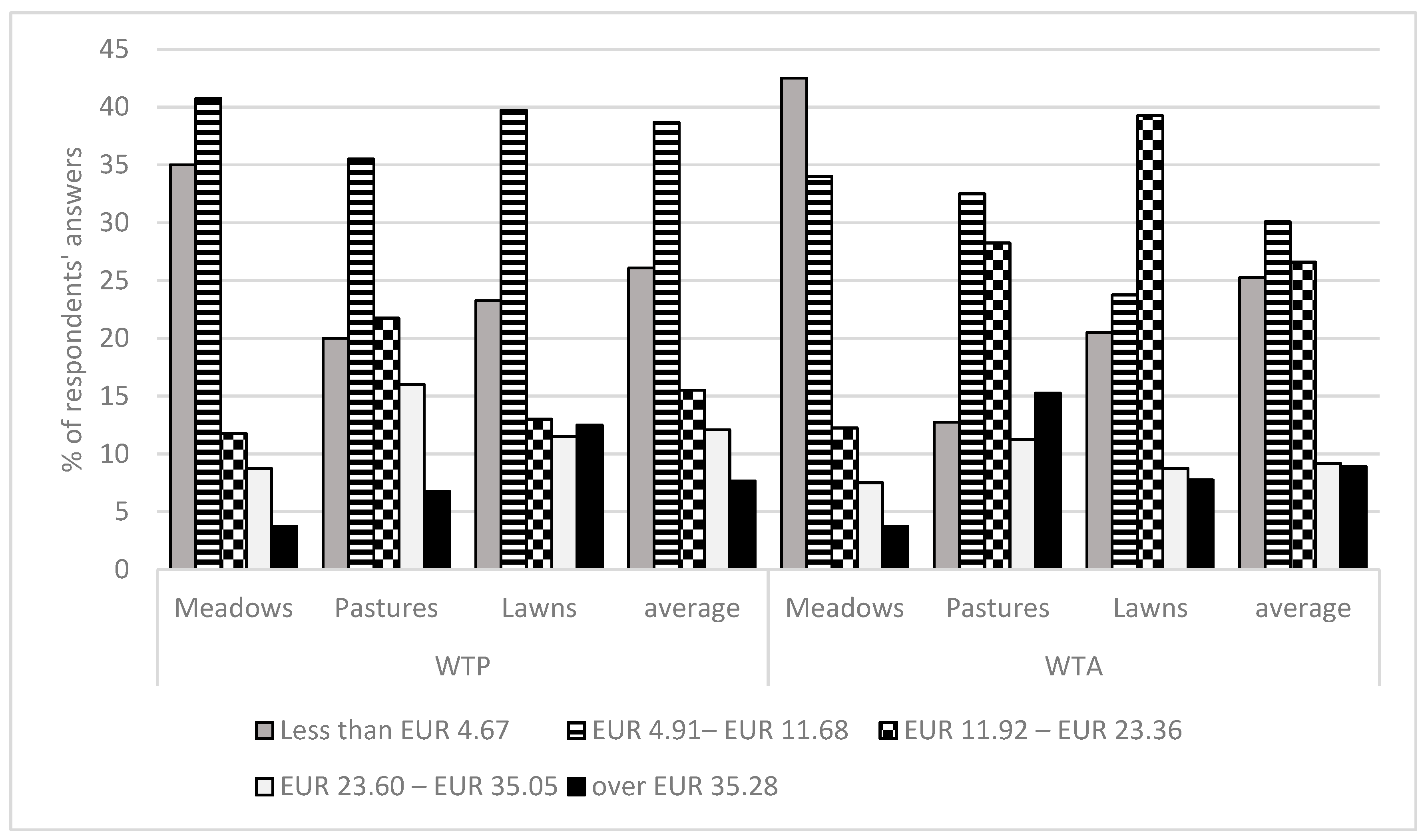

3.2. Estimated Monetary Valuation of Cultural Ecosystem Services

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Grassland ecosystems (meadows, pastures, and lawns) are clearly perceived as valuable sources of cultural ecosystem services, particularly in terms of recreation, relaxation, and aesthetics. Respondents demonstrated a differentiated yet conscious assessment of the role these landscapes play in enhancing quality of life and the experience of space.

- Lawns received the highest ratings in terms of recreational and leisure attractiveness, especially among students in landscape architecture-related fields. In contrast, meadows were considered the most aesthetically pleasing, achieving the highest Aesthetic Attractiveness Index (AAI). These results indicate that different types of grasslands contribute to different dimensions of cultural ecosystem services, reflecting users’ diverse visual preferences and cultural associations.

- Statistically significant differences in WTP and WTA values confirm the influence of the respondents’ field of study and place of residence. Students of agricultural and animal science disciplines rated pastures and meadows more highly, whereas those from spatial planning and landscape architecture disciplines tended to prefer lawns.

- Respondents living in urban areas consistently declared higher WTP and WTA values than those from rural areas, suggesting that access to and demand for green spaces are largely shaped by the spatial context of everyday life.

- Although lawns and pastures yielded higher per-hectare values, meadows generated the highest total cultural ecosystem service value due to their larger spatial extent in the Lublin region. This result highlights the importance of combining intensity of perception with spatial scale in valuation studies.

- The discrepancy between lawns’ low aesthetic ratings (AAI) and their high recreational attractiveness (RLAI) indicates a complex perception structure of cultural services. This divergence may stem from their functional qualities (e.g., accessibility, usability), which outweigh visual appeal. Such asymmetries underscore the multidimensionality of human–landscape relationships and the necessity of evaluating cultural services through a multi-indicator approach.

- The divergence between WTP and WTA values—where compensation was valued higher than willingness to pay—reflects not only economic rationality but also deeper psychological and cultural mechanisms. This asymmetry is consistent with findings in environmental economics and supports the relevance of contingent valuation for capturing intangible dimensions of nature’s value.

- The study provides empirical foundations for integrating cultural ecosystem services into local spatial planning, particularly in the context of grassland conservation and green infrastructure development. Management strategies should be aligned with social perceptions of these areas to enhance both public acceptance and policy effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ignatieva, M.; Hedblom, M. An Alternative Urban Green Carpet: How Can We Move to Sustainable Lawns in a Time of Climate Change? Science 2018, 362, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, C.J.; Carignan-Guillemette, L.; Turcotte, C.; Maire, V.; Proulx, R. Ecological and Economic Benefits of Low-Intensity Urban Lawn Management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 57, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junge, X.; Schüpbach, B.; Walter, T.; Schmid, B.; Lindemann-Matthies, P. Aesthetic Quality of Agricultural Landscape Elements in Different Seasonal Stages in Switzerland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Olejnik, A.; Mocior, E.; Tokarczyk, N. Human Perceptions of Cultural Ecosystem Services of Semi-Natural Grasslands: The Influence of Plant Communities. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 46, 101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southon, G.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Dunnett, N.; Hoyle, H.; Evans, K.L. Biodiverse Perennial Meadows Have Aesthetic Value and Increase Residents’ Perceptions of Site Quality in Urban Green-Space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.R.; Koto, R.; De Boni, A.; Palmisano, G.O.; Cioffi, M.; Roma, R. Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Review of Methods and Tools for Economic Evaluation. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, G.; Xu, Y.; Xu, B. Spatial Impact of Rural Landscape Pattern on Ecosystem Service in Hangzhou. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 32, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindale, S.; Vicario-Modro, V.; Gallardo-Cobos, R.; Hunter, E.; Miskolci, S.; Newell Price, P.; Sánchez-Zamora, P.; Sonnevelt, M.; Ojo, M.; McInnes, K.; et al. Citizen Perceptions and Values Associated with Ecosystem Services from European Grassland Landscapes. Land Use Policy 2023, 127, 106574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, V.H.; Fox, N.; Richter, F.J.; Andreatta, D.; Chaiallah, A. Powerful Flowers: Public Perception of Grassland Aesthetics Is Strongly Related to Management and Biodiversity. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Chiang, J.-T.; Ko, P.-F. The Benefits of Tourism for Rural Community Development. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson, J.; Bullock, J.M.; Egoh, B.; Everson, C.; Everson, T.; O’Connor, T.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Smith, H.G.; Lindborg, R. Grasslands—More Important for Ecosystem Services Than You Might Think. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipińska, H.; Kłopotowska, A.; Włosek, D. The Contingent Valuation Method in the Study of Ecosystem Services on the Example of the Urban Natural System of Lubartów. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 471, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P.; He, J.; Hsu, M.J. Challenges to Understanding and Managing Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Global South. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausi, L.; Amodio, M.; Sebastiani, A.; Fusaro, L.; Manes, F. Assessing Cultural Ecosystem Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic at the Garden of Ninfa (Italy). Ann. Bot. 2022, 12, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.; Quatrini, S.; Lieberher, E.; Tindale, S.; Sanchez Zamora, P.; Gallardo Cobos, R.; Miskolci, S.; Johansson, C.; Nybom, J.; Cano Vergara, B.; et al. The Effectiveness of Policies Promoting Sustainable Permanent Grasslands Across Five European Countries: Mapping, Understanding, and Key Stakeholder Perceptions; WP4; Deliverable 4.1c; SUPER-G (Sustainable Permanent Grassland Systems and Policies); EC Project Number 774124–2; Newcastle University: Newcastle, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Junge, X.; Matthies, D. The Influence of Plant Diversity on People’s Perception and Aesthetic Appreciation of Grassland Vegetation. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribot, A.-S.; Deter, J.; Mouquet, N. Integrating the Aesthetic Value of Landscapes and Biological Diversity. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20180971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkonen, J.; Raatikainen, K.J. Aesthetics in Biodiversity Conservation. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2024, 82, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoslada, M.; Vinogradovs, I.; Ruskule, A.; Veidemane, K.; Nikodemus, O.; Kasparinskis, R.; Sepp, K.; Gulbinas, J. A Multitiered Approach for Grassland Ecosystem Services Mapping and Assessment: The Viva Grass Tool. One Ecosyst. 2018, 3, e25490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.N. Kwestionariusze, Wywiady, Pomiary Postaw; Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo: Poznań, Poland, 2004; pp. 35–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zydroń, A.; Sikora, A. Valuation of the Sołacki Park in Poznań Using the Contingent Valuation Method. Stud. Pr. Wydz. Nauk Ekon. Zarz. Univ. Szczecin 2015, 42, 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lupa, P. Quantification of Selected Ecosystem Services at the Local Level: The Case of Krajenka Municipality. Ph.D. Thesis, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland, 2016; pp. 96–160. [Google Scholar]

- National Bank of Poland. Table No. 077/A/NBP/2025 of 2025-04-22. Available online: https://nbp.pl/en/archiwum-kursow/table-no-077-a-nbp-2025-of-2025-04-22/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of Agriculture; Statistics Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; p. 432.

- Woźniak-Kostecka, I.; Lipińska, H.; Sosnowska, M.; Wyłupek, T. Directions of changes in the use of permanent grasslands in the Lubelskie Voivodeship in the years 1990–2018. Grassl. Sci. Pol. 2022, 22, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gobster, P.H.; Nassauer, J.I.; Daniel, T.C.; Fry, G. The Shared Landscape: What Does Aesthetics Have to Do with Ecology? Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křůmalová, V.; Pražan, J.; Drlík, J. Valuation of Selected Public Goods from Agriculture; Výzkumný Ústav Zemědělské Ekonomiky: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, M.; Birnbaum, L.; Bosveld, A.T.; Brunström, B.; Cook, P.; Feeley, M.; Giesy, J.P.; Hanberg, A.; Hasegawa, R.; Kennedy, S.W.; et al. Toxic Equivalency Factors (TEFs) for PCBs, PCDDs, PCDFs for Humans and Wildlife. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Martín, F.; Martín-López, B.; García-Llorente, M.; Aguado, M.; Benayas, J.; Montes, C. Unraveling the relationships between ecosystem services and human well-being in Spain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, C.; Rehdanz, K. Preferences for cultural urban ecosystem services: Comparing attitudes, perception, and use. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marselle, M.R.; Bowler, D.E.; Watzema, J.; Eichenberg, D.; Kirsten, T.; Bonn, A. Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallimer, M.; Irvine, K.N.; Skinner, A.M.; Davies, Z.G.; Rouquette, J.R.; Maltby, L.L.; Warren, P.H.; Armsworth, P.R.; Gaston, K.J. Biodiversity and the feel-good factor: Understanding associations between self-reported human well-being and species richness. BioScience 2012, 62, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Bruce Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O.’Neill, R.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk-Marciniak, R.; Frankiewicz, P.; Krauze, K. Socio-cultural valuation of Polish agricultural landscape components by farmers and its consequences. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 74, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B.; Knez, I.; Hedblom, M.; Ode Sang, Å. Effects of Biodiversity and Environment-Related Attitude on Perception of Urban Green Space. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechtman, O. Visual Perception of Agricultural Cultivated Landscapes: Key Components as Predictors for Landscape Preferences. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakosy, D.; Motivans, E.; Stefan, V.; Nowak, A.; Świerszcz, S.; Feldmann, R.; Kuhn, E.; Geppert, C.; Venkataraman, N.; Sobieraj-Betlińska, A.; et al. Intensive Grazing Alters the Diversity, Composition and Structure of Plant–Pollinator Interaction Networks in Central European Grasslands. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poczta, J. Natural and Sightseeing Values and Physical Recreation in Agritourism Farms. In Turystyka Kulturowa; Mikos von Rohrscheidt, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo: Poznań, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackenburg, D.; McDonough, K.; Kadykalo, A.; Marquina, T.; Winkler, K. Ecosystem Services in Postsecondary and Professional Education: An Overview of Programs and Courses. Ecosyst. People 2023, 19, 2201351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuik, O. The Avoidance Costs of Greenhouse Gas Damage: A Meta-Analysis. In CASES Project; WP3; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; pp. 34–65. [Google Scholar]

- Goliński, T.; Foltynowicz, Z. Valuation of Ecosystem Services for Implementing Innovative Clean Technology. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising cultural ecosystem services: A. novel framework for research and critical engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; von der Dunk, A. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Chapman, M.; Díaz, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; Jax, K.; Klain, S.; et al. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Robinson, G.M. The influence of place attachment and experience on people’s perceptions of land use options. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuik, O. Valuation of Ecosystem Services in Dutch Rural Areas: A Stated Preference Approach; Institute for Environmental Studies (IVM), VU University Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tessema, M.W.; Abebe, B.G. Public Perception on the Role of Urban Green Infrastructure Development and Land Use Management in Rapidly Urbanized Countries: The Case of Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 17, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, R.; Buijs, A.E.; Snep, R.P.H. Urban green spaces and perceived ecosystem services: A. cross-European analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 230, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppelt, R.; Dormann, C.F.; Eppink, F.V.; Lautenbach, S.; Schmidt, S. A Quantitative Review of Ecosystem Service Studies: Approaches, Shortcomings and the Road Ahead. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas-Defossez, F.; Hart, K.; Mottershead, D.H.; Maréchal, A.; Allen, B. Feeding Europe: Agriculture and Sustainable Food Systems; Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP): London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Kronenberg, J.; Kaczmarek, T. Mainstreaming ecosystem services into spatial planning: The role of indicators. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 221, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambonnet, L.; Vugteveen, P.; Turnhout, E. Policy integration of ecosystem services in spatial planning: Perceptions and action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 96, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Declared Monetary Ranges [EUR·ha−1] | Values Used for Calculation [EUR] |

|---|---|---|

| WTP, WTA | <EUR 4.67 | EUR 4.67 |

| EUR 4.67–11.68 | EUR 11.68 | |

| EUR 11.92–23.36 | EUR 23.36 | |

| EUR 23.60–35.05 | EUR 35.05 | |

| >EUR 35.05 | EUR 70.09 |

| Index | Meadows | Pastures | Lawns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recreational and Leisure Attractiveness (RLAI) | 27 | 21 | 44 |

| Normalised Recreational and Leisure Attractiveness (RLAI!) | 0.34 | 0.11 | 1.00 |

| Aesthetic Attractiveness (AAI) | 26.36 | 23.46 | 9.06 |

| Normalised Aesthetic Attractiveness (AAI!) | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.00 |

| Grassland Type | WTP [EUR/Person] | WTA [EUR/Person] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | AS | SP | L | A | AS | SP | L | |

| Meadows | 15.19 | 13.55 | 14.02 | 17.06 | 14.49 | 15.89 | 14.95 | 12.38 |

| Pastures | 23.60 | 19.39 | 23.13 | 16.32 | 26.87 | 25.93 | 23.83 | 25.93 |

| Lawns | 19.39 | 18.22 | 21.26 | 27.10 | 16.59 | 19.86 | 20.79 | 28.04 |

| Average | 19.39 | 17.06 | 19.36 | 20.09 | 19.16 | 20.56 | 19.86 | 22.20 |

| Grassland Type | WTP | WTA |

|---|---|---|

| Meadows | p = 0.899 | p = 0.907 |

| Pastures | p < 0.001 * | p = 0.338 |

| Lawns | p = 0.230 | p = 0.236 |

| Academic Discipline | WTP | WTA |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | p < 0.001 * | p < 0.001 * |

| Animal science | p = 0.085 | p < 0.001 * |

| Spatial planning | p < 0.001 * | p < 0.001 * |

| Landscaping | p < 0.001 * | p < 0.001 * |

| Indicator | Significant Dependent Variables (p < 0.05) | Coefficient | Interpretation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTP—Meadows | Place of residence: rural | −74.34 | Respondents from rural areas declared significantly lower WTP for meadows. | 0.26 |

| Field of study | – | No significant differences. | ||

| WTA—Meadows | Place of residence: rural | −66.47 | Respondents from rural areas expect lower compensation for the loss of meadows. | 0.21 |

| Field of study | +31.32 | Students of agriculture, animal science, and spatial management assign significantly higher WTA values to meadows than landscape architecture students. | ||

| WTP—Pastures | Place of residence: rural | −82.96 | Respondents from rural areas expect significantly lower compensation for the loss of pastures. | 0.25 |

| Field of study | +38.64 | Agriculture students declare higher WTP for pastures (confirmed by Chi2 test). | ||

| WTA—Pastures | Place of residence: rural | −105.82 | Respondents from rural areas expect significantly lower compensation for the loss of pastures. | 0.25 |

| Field of study | +36.46 | Students of agriculture and animal science expect significantly higher compensation for loss of access to pastures than landscape architecture students. | ||

| WTP—Lawns | Place of residence: rural | −118.54 | Respondents from rural areas declared significantly lower amounts for access to lawns compared to urban residents. | 0.35 |

| Field of study | – | Best-fitting model among all, although no statistically significant predictors were found. | ||

| WTA—Lawns | Place of residence: rural | −66.47 | Respondents from rural areas expect lower compensation for the loss of lawns. | 0.33 |

| Field of study | – | No significant differences. |

| Indicators | Grassland Type | M | Md | SD | SE | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTP [EUR·ha−1] | Meadows | a 15.04 | 11.71 | 14.45 | 0.91 | 4.68 | 70.26 |

| Pastures | b 20.56 | 11.71 | 17.07 | 1.08 | 4.68 | 70.26 | |

| Lawns | b 21.66 | 11.71 | 20.77 | 1.31 | 4.68 | 70.26 | |

| WTA [EUR·ha−1] | Meadows | a 14.49 | 11.71 | 14.51 | 0.92 | 4.68 | 70.26 |

| Pastures | b 25.70 | 23.42 | 20.92 | 1.32 | 4.68 | 70.26 | |

| Lawns | b 21.26 | 23.42 | 16.72 | 1.06 | 4.68 | 70.26 | |

| Total cultural service value [EUR·ha−1] | Meadows | a 29.44 | 23.42 | 25.67 | 1.62 | 9.37 | 140.52 |

| Pastures | b 46.26 | 35.13 | 32.81 | 2.07 | 9.37 | 140.52 | |

| Lawns | b 42.76 | 35.13 | 35.98 | 2.28 | 9.37 | 140.52 |

| Grassland Type | Estimated Area [ha] | Total Value per ha [WTP + WTA] [EUR·ha−1] | Total Value of Cultural Ecosystem Services [EUR·year−1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meadows | 170,777 | 29.44 | c 5,027,547.20 |

| Pastures | 85,388 | 46.26 | b 3,950,192.52 |

| Lawns | 40,128 | 42.76 | a 1,715,753.27 |

| Total | 296,293 | 118.46 | 10,693,492.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wyłupek, T.; Lipińska, H.; Kępkowicz, A.; Adamczyk-Mucha, K.; Lipiński, W.; Franczak, S.; Duniewicz, A. Cultural Ecosystem Services of Grassland Communities: A Case Study of Lubelskie Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156697

Wyłupek T, Lipińska H, Kępkowicz A, Adamczyk-Mucha K, Lipiński W, Franczak S, Duniewicz A. Cultural Ecosystem Services of Grassland Communities: A Case Study of Lubelskie Province. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156697

Chicago/Turabian StyleWyłupek, Teresa, Halina Lipińska, Agnieszka Kępkowicz, Kamila Adamczyk-Mucha, Wojciech Lipiński, Stanisław Franczak, and Agnieszka Duniewicz. 2025. "Cultural Ecosystem Services of Grassland Communities: A Case Study of Lubelskie Province" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156697

APA StyleWyłupek, T., Lipińska, H., Kępkowicz, A., Adamczyk-Mucha, K., Lipiński, W., Franczak, S., & Duniewicz, A. (2025). Cultural Ecosystem Services of Grassland Communities: A Case Study of Lubelskie Province. Sustainability, 17(15), 6697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156697