Using Machine Learning to Model the Acceptance of Domestic Low-Carbon Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Models for Understanding the Acceptance of Low-Carbon Technologies

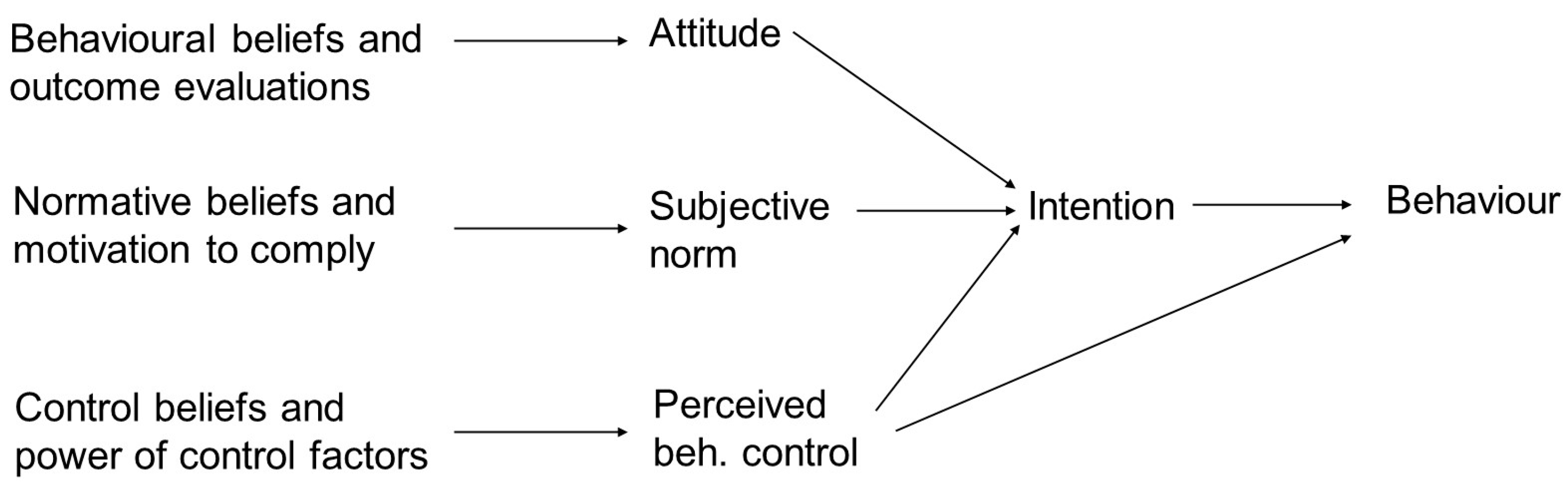

2.2. Acceptance Through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behaviour

2.3. Acceptance Endpoints

2.4. Acceptance and Approach to Low-Carbon Technology Installation

2.5. Low-Carbon Technology Acceptance and Occupier Status

2.6. Machine Learning for Acceptance Modelling

3. Current Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Participants

4.3. Materials

4.4. Procedure

4.5. Data Analysis

4.5.1. Supervised Machine Learning and Criteria for Machine-Learning Analysis

4.5.2. Hyperparameter Selection in Machine Learning Analysis

4.5.3. Implementation of Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptives

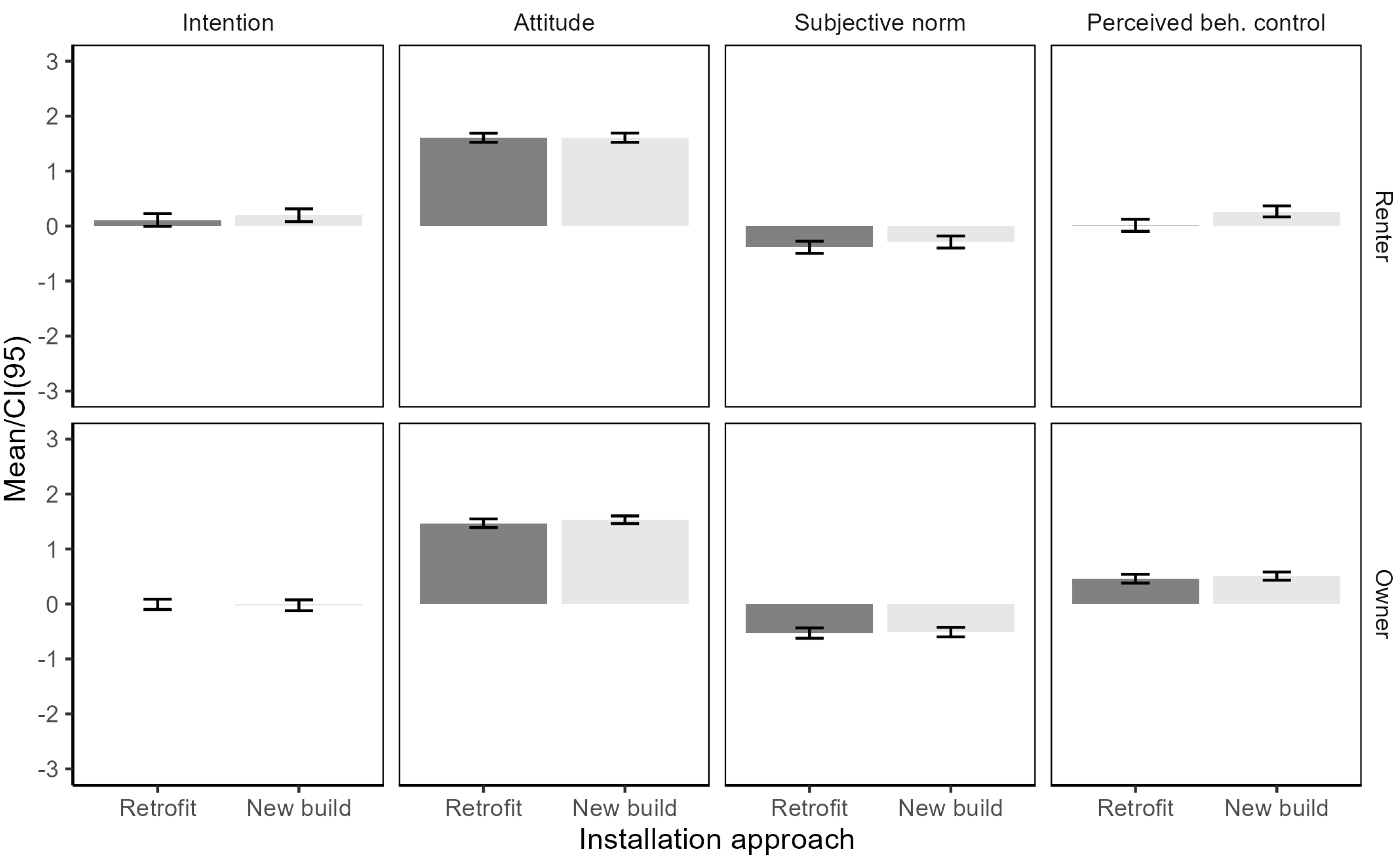

5.1.1. Main Components of the Theory of Planned Behaviour

5.1.2. Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept

5.2. Associations of Adoption Intention and Related Outcomes

5.3. Model Evaluation

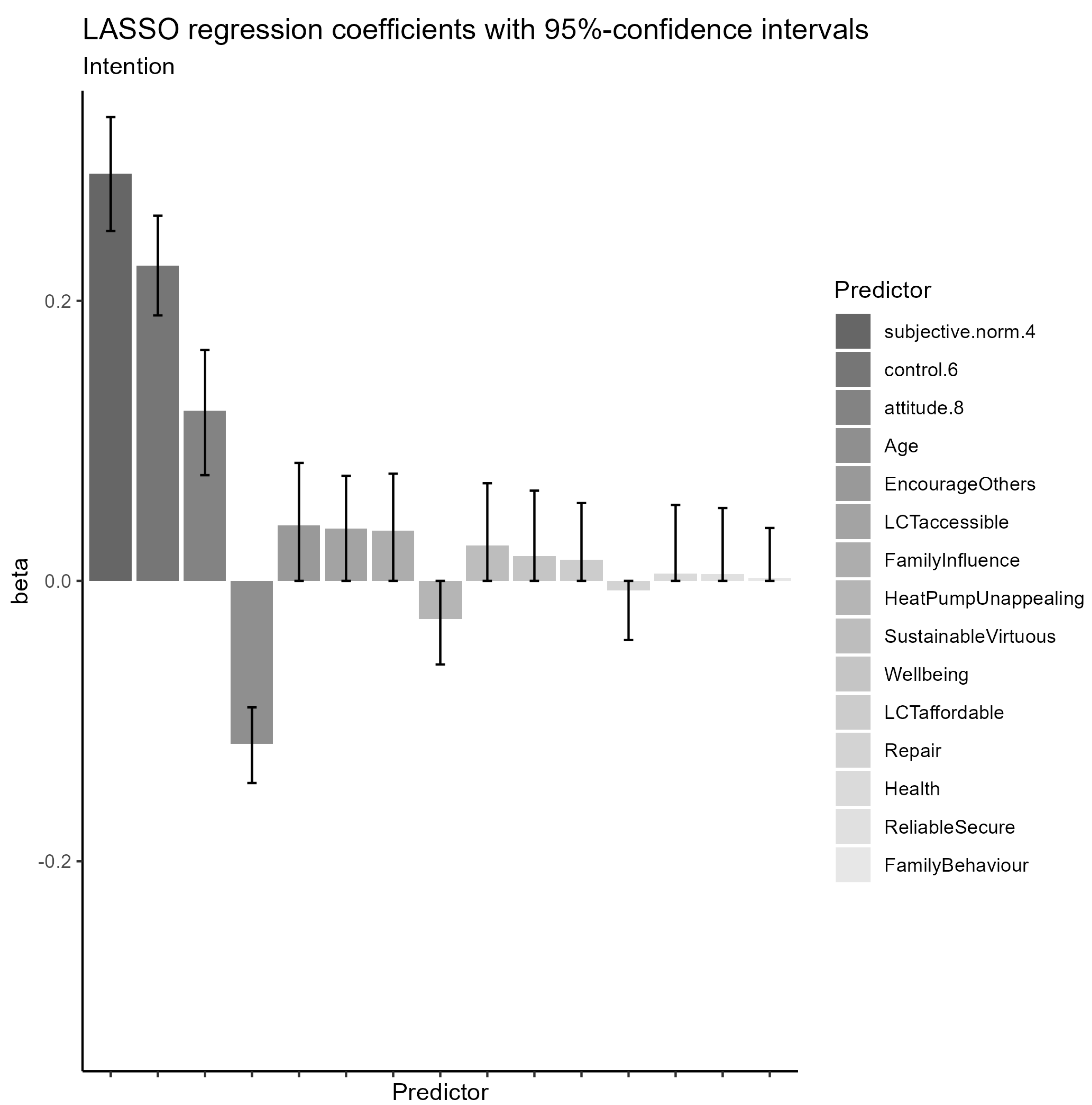

5.3.1. Adoption Intention: Hypotheses 1, 3abc, and 7

5.3.2. Willingness to Pay for/Willingness to Accept a Low-Carbon Technology Home: Hypotheses 3babc, 7

5.3.3. Attitude Towards Living in a Low-Carbon Home: Hypotheses 4, 7

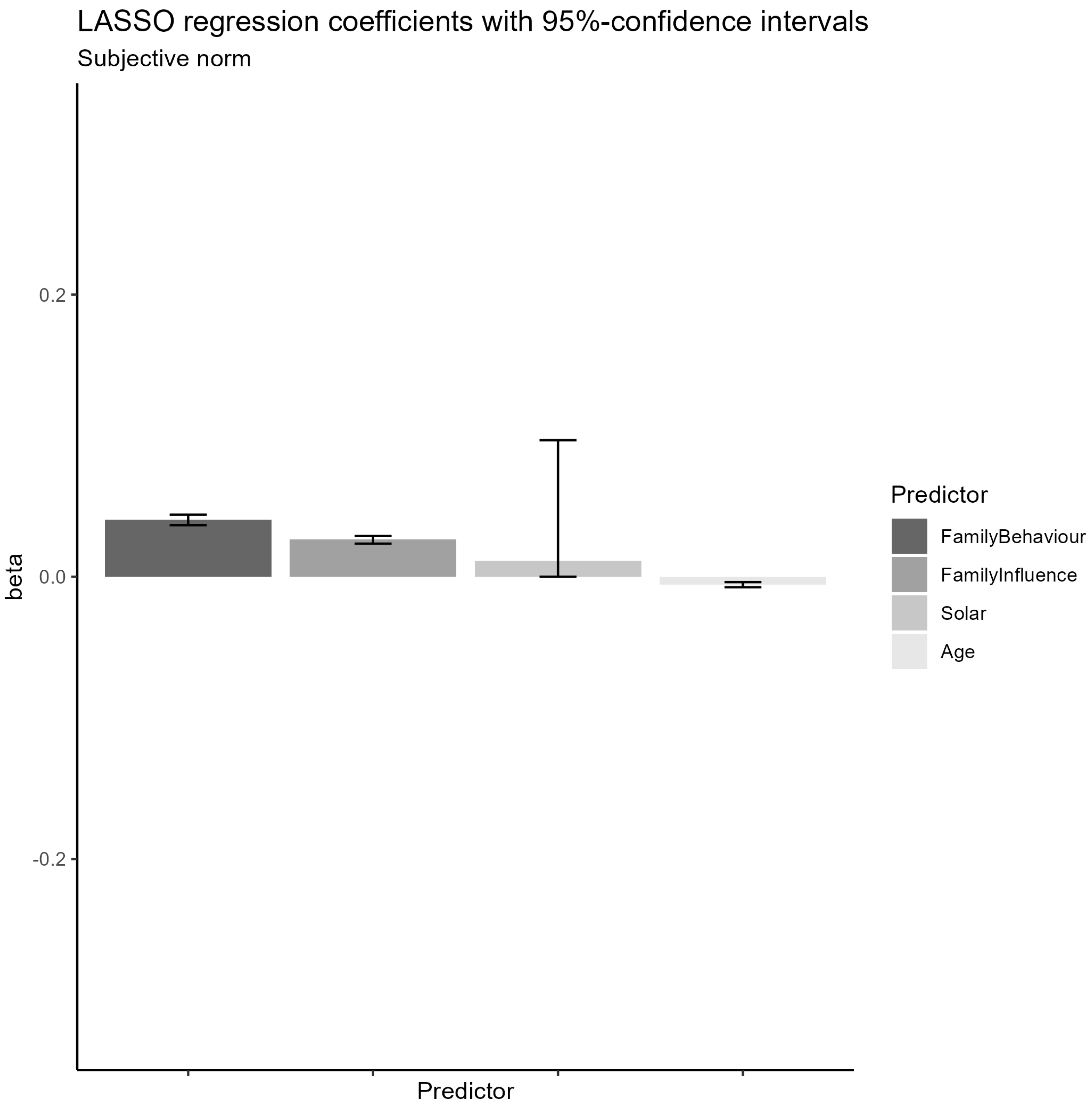

5.3.4. Subjective Norm: Hypotheses 5, 7

5.3.5. Perceived Behavioural Control: Hypotheses 2, 6, 7

5.3.6. Summary of Results

6. Discussion

6.1. The Acceptance of Low-Carbon Technologies

6.1.1. Evaluation of Hypotheses

6.1.2. Recommendations and Implications for Policy

6.2. Evaluation of the Use of Machine Learning

6.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCT | Low-carbon technology |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behaviour |

| WTA | Willingness to accept |

| WTP | Willingness to pay |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). 2019 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emissions, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/3da9daf9-ef75-4a37-b3da-a09224e299dc/2019_Global_Status_Report_for_Buildings_and_Construction.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Belussi, L.; Barozzi, B.; Bellazzi, A.; Danza, L.; Devitofrancesco, A.; Fanciulli, C.; Ghellere, M.; Guazzi, G.; Meroni, I.; Salamone, F.; et al. A review of performance of zero energy buildings and energy efficiency solutions. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.S.; Fitiwi, D.Z.; Curtis, J. Heat pumps and our low-carbon future: A comprehensive review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Hu, M.; Deetman, S.; Steubing, B.; Lin, H.X.; Hernandez, G.A.; Harpprecht, C.; Zhang, C.; Tukker, A.; Behrens, P. Global greenhouse gas emissions from residential and commercial building materials and mitigation strategies to 2060. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metta, J.; An, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, L. Potentials and opportunities towards the low carbon technologies—From literature review to new classification. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 1013–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobus, N.V.; Knyazeva, M.A.; Popova, A.F.; Kulikovskiy, M.S. Carbon footprint reduction and climate change mitigation: A review of the approaches, technologies, and implementation challenges. C 2023, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldson, A.; Sudmant, A.; Khreis, H.; Papargyropoulou, E. The Economic and Social Benefits of Low-Carbon Cities: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Coalition for Urban Transitions. London and Washington, DC. 2018. Available online: http://newclimateeconomy.net/content/cities-working-papers (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kennedy, M.; Basu, B. Overcoming barriers to low carbon technology transfer and deployment: An exploration of the impact of projects in developing and emerging economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Summary. In Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 51–148. ISBN 978-1-00-915792-6. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/5B255A3E29E6976F492038261E811206 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhm, P.; Baumann, M.J.; Weil, M. Approaching social acceptance of energy technologies: Ten European papers showcasing statistical analyses–a targeted review. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2025, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.; Long, R.; Xu, Z.; Cao, Q. Factors affecting low-carbon consumption behavior of urban residents: A comprehensive review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shen, B.; Han Springer, C.; Hou, J. What prevents us from taking low-carbon actions? A comprehensive review of influencing factors affecting low-carbon behaviors. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, P.; Marques, C.; Reis, E. Willingness to pay for environmental quality: The effects of pro-environmental behavior, perceived behavior control, environmental activism, and educational level. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211025256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism1. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on Attitude-Behavior Relationships: A Natural Experiment with Curbside Recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, A.M. A comparative study of theoretical behaviour change models predicting empirical evidence for residential energy conservation behaviours. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, H.; Fuerst, F. Modelling energy retrofit investments in the UK housing market: A microeconomic approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2015, 4, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Dessi, F.; Bonaiuto, M. A meta-analysis on the drivers and barriers to the social acceptance of renewable and sustainable energy technologies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 114, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Benn, Y.; Chang, B.P.I. Antecedents and consequences of monitoring domestic electricity consumption. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, M.; Molla, A.; Cooper, V. Behavioural and environmental sustainability determinants of residential energy management information systems use. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Ahmad, M.; Othman, A.S.; Shaari, Z.B.H.; Masukujjaman, M. Factors affecting photovoltaic solar technology usage intention among households in Malaysia: Model integration and empirical validation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almrafee, M.; Akaileh, M. Customers’ purchase intention of renewable energy in Jordan: The case of solar panel systems using an extended theory of planned behavior (TPB). Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023, 18, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.D.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, T.M.N. Extend theory of planned behaviour model to explain rooftop solar energy adoption in emerging market. Moderating mechanism of personal innovativeness. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Kaur, P. Predicting customers’ intentions to adopt the solar net metering system in India. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023, 17, 1252–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundheim, S.H.; Vesely, S.; Nayum, A.; Klöckner, C.A. From vague interest to strong intentions to install solar panels on private homes in the North—An analysis of psychological drivers. Renew. Energy 2021, 165, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Dagiliūtė, R.; Juknys, R. The determinants of renewable energy usage intentions using theory of planned behaviour approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, J. Loads of green washing—Can behavioural economics increase willingness-to-pay for efficient washing machines in the UK? Energy Policy 2012, 50, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, G.; McCoy, D. Market failures and willingness to accept smart meters: Experimental evidence from the UK. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 118, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.; Curtis, J. Willingness-to-pay and free-riding in a national energy efficiency retrofit grant scheme. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; Gómez-Bayona, L.; Moreno-López, G.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Gallardo-Canales, R. Influence of environmental awareness on the willingness to pay for green products: An analysis under the application of the theory of planned behavior in the Peruvian market. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1282383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Willingness to pay for what? Testing the impact of four factors on willingness to pay for facilitating and sanctioning energy policy instruments. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipwood, T. Adapting owner-occupied dwellings in the UK: Lessons for the future. Build. Cities 2022, 3, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, M.; Kivimaa, P. Role of knowledge and policies as drivers for low-energy housing: Case studies from the United Kingdom. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1402–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Garmston, H. Building regulations in energy efficiency: Compliance in England and Wales. Energy Policy 2012, 45, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.J.; Maddock, C.A.; Musselwhite, C.B.A. These are tenants not guinea pigs: Barriers and facilitators of retrofit in Wales, United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 111, 103462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Wrapson, W.; Henshaw, V.; Guy, S. Low carbon heating and older adults: Comfort, cosiness and glow. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, Á.; Byrne, M.; Armstrong, S.; Sheahan, J.; Coggins, A.M. A pre and post evaluation of indoor air quality, ventilation, and thermal comfort in retrofitted co-operative social housing. Build. Environ. 2017, 122, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, F.; Straub, A.; Mlecnik, E. Consultancy Centres and Pop-Ups as Local Authority Policy Instruments to Stimulate Adoption of Energy Efficiency by Homeowners. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023: Headline Report; DLUHC: London, UK, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/english-housing-survey-2022-to-2023-headline-report (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- McKee, K.; Soaita, A.M.; Hoolachan, J. ‘Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 1468–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; Moore, D.; MacDonald, S. Exploring the adoption of low carbon technologies by Scottish housing associations. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2011, 6, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, M. Building better models: Prediction, replication, and machine learning in the social sciences. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2015, 659, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, N.; Ratković, K.; Farahani, H.; Watson, P. A practical applications guide to machine learning regression models in psychology with Python. Methods Psychol. 2024, 11, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, M.D. Incorporating machine learning into sociological model-building. Sociol. Methodol. 2024, 54, 217–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.K.; Kaltoft, M.K.; Dowie, J. Inferring Causality Is Preference-Sensitive: We Need a Book of Who as Well as Why. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2023, 309, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behaviour Questionnaire. 2019. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Cotton, M.; Van Schaik, P.; Vall, N.; Lorrimer, S.; Mountain, A.; Stubbs, R.; Leighton, C.; Leon, E.S.; Imani, E. Just transitions and sociotechnical innovation in the social housing sector: An assemblage analysis of residents’ perspectives. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 225–288. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning; Lulu.com: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shen, M.; Chu, M. Why is green consumption easier said than done? Exploring the green consumption attitude-intention gap in China with behavioral reasoning theory. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E.; Naeyaert, S.; Van Hove, S.; Pelka, S.; Preuß, S.; Gabriel, M.; Conradie, P.; Ponnet, K. Transitioning towards sustainable heating: A mixed-methods study of heat pump acceptance among Flemish homeowners. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 126, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, I.; Hameed, I.; Ali, R. Predicting household sign up for solar energy: An empirical study based on the extended theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023, 17, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Xu, X.; Frey, S. Who wants solar water heaters and alternative fuel vehicles? Assessing social-psychological predictors of adoption intention and policy support in China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ying, X.; Gao, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z. Applying an extended theory of planned behavior to predict willingness to pay for green and low-carbon energy transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketiah, E.; Song, H.; Gu, T.; Adjei, M.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Obuobi, B. How willing are residents to accept sustainable energy from food waste generated by anaerobic digestion projects? Energy 2024, 298, 131387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, K.; Zhang, J.; Chang, H. Environmental knowledge, risk attitude, and households’ willingness to accept compensation for the application of degradable agricultural mulch film: Evidence from rural China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuch, A.N.; Van Schaik, P.; Hornbæk, K. Leisure and work, good and bad: The role of activity domain and valence in modeling user experience. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2016, 23, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M. The thing and I (summer of’17 remix). In Funology 2 Usability Enjoyment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, K.; Pummerer, L.; Hornsey, M.J.; Sassenberg, K. Pro-vaccination subjective norms moderate the relationship between conspiracy mentality and vaccination intentions. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbersen, H.; Hofmann, L.A.; Ruiz-Fernández, S. How people evaluate anti-corona measures for their social spheres: Attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansma, S.R.; Gosselt, J.F.; de Jong, M.D. Kissing natural gas goodbye? Homeowner versus tenant perceptions of the transition towards sustainable heat in the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Act 2023 [c. 52]. Stationary Office: London, UK, 2023. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/52 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Stefanini, S. UK Drawing Up a Net Zero Public Participation Strategy to Bring People on Board, Carbon Pulse. April 2025. Available online: https://carbon-pulse.com/384517/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Cotton, M. Policy, Market, and Skills Barriers to Heat Pump Deployment in the United Kingdom. In Global Energy Transition and Sustainable Development Challenges, Models and Regions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. Press Release: Help to Save Households Money and Deliver Cleaner Heat to Homes; Department for Energy Security and Net Zero: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/help-to-save-households-money-and-deliver-cleaner-heat-to-homes (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Günther, A.; Engel, L.; Hornsey, M.J.; Nielsen, K.S.; Roy, J.; Steg, L.; Tam, K.-P.; van Valkengoed, A.M.; Wolske, K.S.; Wong-Parodi, G.; et al. Psychological and contextual determinants of clean energy technology adoption. Nat. Rev. Clean Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, R.; Morgan, G.; Dharmage, S.; Marks, G.; Cowie, C. Scoping review to understand the potential for public health impacts of transitioning to lower carbon emission technologies and policies. Environ. Res. Commun. 2020, 2, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, O.; Holdsworth, S.; Wong, P.S.; Hayes, J. Upskilling plumber gasfitters for hydrogen: An empirical study using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.; Nair, A.M.; George, J.; Alapatt, B.P. Predictive Modelling of Heart Disease: Exploring Machine Learning Classification Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Distributed Computing and Optimization Techniques (ICDCOT), Bengaluru, India, 15–16 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, L.F. Xgboost: The King of Machine Learning Algorithms. 2023. Available online: https://medium.com/latinxinai/xgboost-the-king-of-machine-learning-algorithms-6b5c0d4acd87 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Weinstein, N.D.; Rothman, A.J.; Sutton, S.R. Stage theories of health behavior: Conceptual and methodological issues. Health Psychol. 1998, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, A.C.; Goel, S.; Williams, K. From cyber benign to cyber malicious: Unveiling the evolution of insider cyber maliciousness from a stage theory perspective. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure Matrix, All Core-Construct Items | Structure Matrix, Final Set of Core-Construct Items | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

| Intention1 | 0.58 | −0.38 | 0.70 | 0.51 | Intention1 | 0.54 | 0.64 | −0.41 | 0.51 |

| Intention2 | 0.73 | −0.17 | 0.54 | 0.30 | Intention4 | 0.34 | 0.80 | −0.40 | 0.40 |

| Intention3 | 0.75 | −0.18 | 0.57 | 0.35 | Intention5 | 0.38 | 0.89 | −0.38 | 0.48 |

| Intention4 | 0.34 | −0.39 | 0.78 | 0.40 | Intention6 | 0.42 | 0.93 | −0.41 | 0.47 |

| Intention5 | 0.38 | −0.37 | 0.85 | 0.48 | Attitude1 | 0.83 | 0.43 | −0.21 | 0.24 |

| Intention6 | 0.43 | −0.40 | 0.89 | 0.47 | Attitude2 | 0.84 | 0.36 | −0.21 | 0.24 |

| Attitude1 | 0.83 | −0.20 | 0.43 | 0.24 | Attitude3 | 0.83 | 0.35 | −0.20 | 0.18 |

| Attitude2 | 0.83 | −0.21 | 0.36 | 0.24 | Attitude4 | 0.79 | 0.33 | −0.23 | 0.28 |

| Attitude3 | 0.83 | −0.20 | 0.35 | 0.17 | Attitude5 | 0.85 | 0.42 | −0.23 | 0.27 |

| Attitude4 | 0.77 | −0.23 | 0.31 | 0.28 | Attitude6 | 0.81 | 0.37 | −0.26 | 0.37 |

| Attitude5 | 0.85 | −0.22 | 0.43 | 0.26 | Attitude7 | 0.88 | 0.35 | −0.20 | 0.24 |

| Attitude6 | 0.79 | −0.27 | 0.34 | 0.37 | Attitude8 | 0.85 | 0.39 | −0.25 | 0.38 |

| Attitude7 | 0.87 | −0.20 | 0.34 | 0.25 | Norm3 | 0.38 | 0.54 | −0.38 | 0.71 |

| Attitude8 | 0.84 | −0.26 | 0.37 | 0.38 | Norm4 | 0.23 | 0.46 | −0.34 | 0.59 |

| Norm1 | 0.71 | −0.28 | 0.46 | 0.50 | Norm5 | 0.30 | 0.45 | −0.36 | 0.89 |

| Norm2 | 0.77 | −0.26 | 0.43 | 0.41 | Norm6 | 0.27 | 0.46 | −0.38 | 0.91 |

| Norm3 | 0.40 | −0.38 | 0.54 | 0.72 | PBC2 | −0.16 | −0.26 | 0.75 | −0.23 |

| Norm4 | 0.24 | −0.34 | 0.45 | 0.59 | PBC3 | −0.16 | −0.34 | 0.87 | −0.34 |

| Norm5 | 0.31 | −0.36 | 0.44 | 0.88 | PBC4 | −0.30 | −0.50 | 0.73 | −0.53 |

| Norm6 | 0.28 | −0.38 | 0.44 | 0.90 | PBC6 | −0.46 | −0.52 | 0.68 | −0.44 |

| PBC1 | −0.51 | 0.60 | −0.65 | −0.60 | PBC7 | −0.47 | −0.60 | 0.72 | −0.52 |

| PBC2 | −0.15 | 0.75 | −0.23 | −0.23 | PBC8 | −0.06 | −0.18 | 0.50 | −0.05 |

| PBC3 | −0.16 | 0.86 | −0.31 | −0.34 | Eigenvalue | 5.94 | 2.91 | 2.99 | 2.67 |

| PBC4 | −0.30 | 0.73 | −0.49 | −0.53 | % variance | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| PBC5 | −0.17 | 0.32 | −0.22 | −0.29 | Omega (reliability) | 0.70 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| PBC6 | −0.47 | 0.69 | −0.53 | −0.45 | |||||

| PBC7 | −0.48 | 0.72 | −0.61 | −0.52 | |||||

| PBC8 | −0.06 | 0.49 | −0.18 | −0.05 | |||||

| Intrinsic Interpretability | Variable Selection | |

|---|---|---|

| Linear regression (LR) | ✓ | - |

| LASSO regression (LASSO) | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ridge regression (RR) | ✓ | ½ |

| Support vector regression (SVR) | ✓ | - |

| Decision tree regression (RT) | ✓ | ✓ |

| Random forest regression (RFR) | - | ✓ |

| Extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) | ✓ | ✓ |

| K-nearest neighbours (k-NNs) | - | NA |

| Neural network (NN) | - | - |

| Variable | Intention | Attitude | Subjective Norm | Perceived Beh. Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.54 |

| Attitude | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| Subjective norm | 0.60 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| Perceived beh. control | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| log WTP | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.24 |

| log WTA | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Installation approach | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Bedrooms | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| Solar | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.17 |

| Insulation | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Smart meter | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Homeowner | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.12 |

| Gender Woman | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| Education Degree Plus | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Work Employed | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Home Type Detached or Semi | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Bills Reduced | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.28 |

| Health | 0.43 | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| Wellbeing | 0.46 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.36 |

| Environment | 0.36 | 0.72 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| Encourage Others | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

| Reliable Energy | 0.41 | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| Sustainable Virtuous | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| Reliable Secure | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| Bills Increased | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.31 | 0.12 |

| Energy Reduced | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.30 | 0.09 |

| Indoor Space Reduced | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| Rent Increased | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| Family Influence | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.33 |

| Landlord Influence | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.30 |

| Family Behaviour | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.60 | 0.33 |

| Residents’ Behaviour | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.35 |

| Government | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.36 |

| Accessible | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.37 |

| LCT affordable | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.40 |

| Space Insufficient | −0.13 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.18 |

| Disruption | −0.27 | −0.37 | −0.19 | −0.26 |

| Repair | −0.26 | −0.34 | −0.23 | −0.26 |

| Knowledge Insufficient | −0.11 | −0.19 | −0.05 | −0.15 |

| Heat Pump unappealing | −0.23 | −0.37 | −0.15 | −0.17 |

| Method | Outcome | R2_train | R2_test | R2_train − R2_test | MSE_train | MSE_test | MSE_train − MSE_test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | Intention | 0.51 | 0.56 | −0.05 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| LASSO-LR | Intention | 0.51 | 0.56 | −0.05 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| ridge-LR | Intention | 0.51 | 0.56 | −0.05 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| XGBoost | Intention | 0.39 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.01 |

| k-NN | Intention | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.52 | −0.52 |

| SVR | Intention | 0.51 | 0.56 | −0.05 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| RT | Intention | 0.75 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.72 | −0.47 |

| RFR | Intention | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.45 | −0.38 |

| NN | Intention | 0.81 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.58 | −0.39 |

| LR | WTA, tenant | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.89 | −0.03 |

| LASSO-LR | WTA, tenant | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.00 |

| ridge-LR | WTA, tenant | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.89 | −0.03 |

| XGBoost | WTA, tenant | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.93 | −0.04 |

| k-NN | WTA, tenant | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.96 | −0.96 |

| SVR | WTA, tenant | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.00 |

| RT | WTA, tenant | 0.63 | −0.49 | 1.12 | 0.37 | 1.49 | −1.12 |

| RFR | WTA, tenant | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.86 | −0.74 |

| NN | WTA, tenant | 0.73 | −0.12 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 1.12 | −0.85 |

| LR | Attitude | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.39 | −0.05 |

| LASSO-LR | Attitude | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.39 | −0.05 |

| ridge-LR | Attitude | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.39 | −0.05 |

| XGBoost | Attitude | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.36 | −0.10 |

| k-NN | Attitude | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.36 | −0.36 |

| SVR | Attitude | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.37 | −0.06 |

| RT | Attitude | 0.82 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.49 | −0.31 |

| RFR | Attitude | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.36 | −0.31 |

| NN | Attitude | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.48 | −0.14 |

| LR | Subjective norm | 0.46 | 0.47 | −0.01 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.01 |

| LASSO-LR | Subjective norm | 0.45 | 0.47 | −0.02 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.02 |

| ridge-LR | Subjective norm | 0.46 | 0.47 | −0.01 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.01 |

| XGBoost | Subjective norm | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.49 | −0.06 |

| k-NN | Subjective norm | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.52 | −0.05 |

| SVR | Subjective norm | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.52 | −0.01 |

| RT | Subjective norm | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.69 | −0.37 |

| RFR | Subjective norm | 0.93 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.51 | −0.44 |

| NN | Subjective norm | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| LR | Perceived behavioural control | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.70 | −0.01 |

| LASSO-LR | Perceived behavioural control | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.00 |

| ridge-LR | Perceived behavioural control | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.70 | −0.01 |

| XGBoost | Perceived behavioural control | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.56 | 0.66 | −0.10 |

| k-NN | Perceived behavioural control | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.74 | −0.06 |

| SVR | Perceived behavioural control | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| RT | Perceived behavioural control | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.94 | −0.53 |

| RFR | Perceived behavioural control | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.66 | −0.57 |

| NN | Perceived behavioural control | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.00 |

| Outcome/Test R2 | Intention | 0.56 | Outcome/Test R2 | Attitude | 0.61 |

| Hypotheses | H1/3a/H7.1 | Hypotheses | H4/H7.4 | ||

| Predictors | Attitude | 0.12 | Predictors | Bills reduced | 0.01 |

| Subjective norm | 0.29 | Health improved | 0.01 | ||

| Perceived beh. control | 0.23 | Wellbeing improved | 0.01 | ||

| Age | −0.12 | Environment improved | 0.01 | ||

| Encourage others | 0.01 | ||||

| Outcome/test R2 | WTA, tenant | 0.11 | Reliable energy | 0.01 | |

| Hypotheses | H3c/H7.2 | Sustainable virtuous | 0.01 | ||

| Predictors | Age | −0.15 | Reliable secure | 0.01 | |

| Installation approach (RF/NB) | 0.12 | ||||

| Outcome/test R2 | Subjective norm | 0.47 | |||

| Hypotheses | H5/H7.5 | ||||

| Predictors | Family Influence | 0.03 | |||

| Outcome/test R2 | WTA, owner, retrofit | 0.02 | Family Behaviour | 0.04 | |

| Hypotheses | H3b/H7.1 | Age | −0.01 | ||

| Predictor | Age | −0.07 | |||

| Bedrooms | 0.10 | Outcome/test R2 | Perceived behavioural control | 0.27 | |

| Solar | −0.23 | Hypotheses | H6/H7.6 | ||

| Predictors | Government | 0.01 | |||

| Outcome/test R2 | WTA, owner, new build | 0.02 | LCT accessible | 0.01 | |

| Hypotheses | H3b/H7.1 | LCT affordable | 0.01 | ||

| Predictor | - | - | Space insufficient | −0.01 | |

| Repair | −0.01 | ||||

| Age | −0.01 | ||||

| Bedrooms | 0.08 | ||||

| Homeowner | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schaik, P.v.; Clements, H.; Karayaneva, Y.; Imani, E.; Knowles, M.; Vall, N.; Cotton, M. Using Machine Learning to Model the Acceptance of Domestic Low-Carbon Technologies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156668

Schaik Pv, Clements H, Karayaneva Y, Imani E, Knowles M, Vall N, Cotton M. Using Machine Learning to Model the Acceptance of Domestic Low-Carbon Technologies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156668

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchaik, Paul van, Heather Clements, Yordanka Karayaneva, Elena Imani, Michael Knowles, Natasha Vall, and Matthew Cotton. 2025. "Using Machine Learning to Model the Acceptance of Domestic Low-Carbon Technologies" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156668

APA StyleSchaik, P. v., Clements, H., Karayaneva, Y., Imani, E., Knowles, M., Vall, N., & Cotton, M. (2025). Using Machine Learning to Model the Acceptance of Domestic Low-Carbon Technologies. Sustainability, 17(15), 6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156668