Toward Sustainable Mental Health: Development and Validation of the Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change (BACC) in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. BACC Development Procedure

2.1.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.1.3. Measures

Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change (BACC)

Mental Health Screening Tool for Anxiety Disorders (MHS: A)

Mental Health Screening Tool for Depressive Disorders (MHS: D)

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Internal Consistency

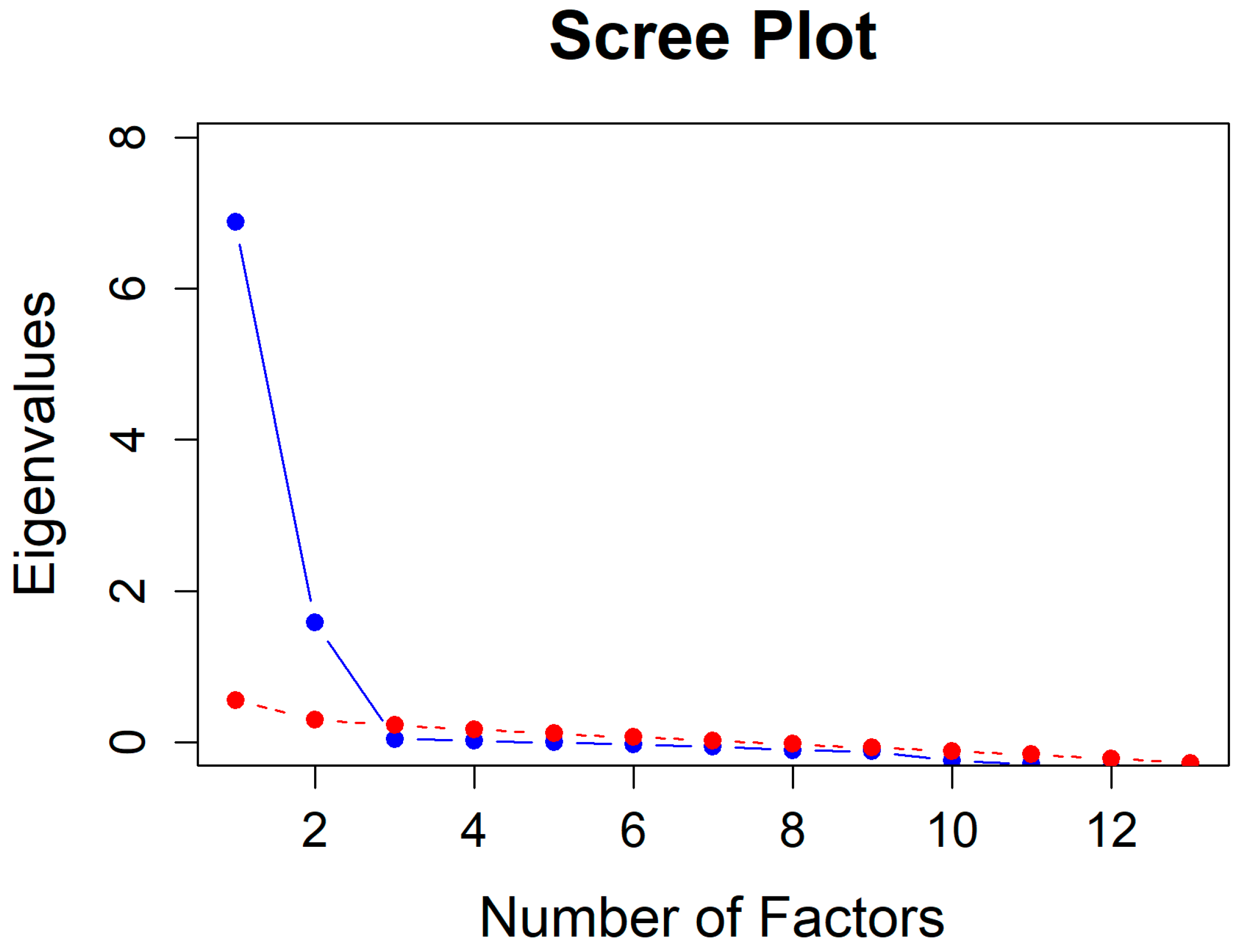

2.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

2.2.3. Correlations with Generalized Anxiety and Depression

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants and Data Collection

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Internal Consistency

3.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.2.3. Correlations with Generalized Anxiety and Depression

3.2.4. Final Items of the BACC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BACC | Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change |

| MHS:A | Mental Health Screening Tool for Anxiety Disorders |

| MHS:D | Mental Health Screening Tool for Depressive Disorders |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| HEAS | Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale |

| RMSR | Root Mean Square of Residuals |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| GAD | Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| CCAS | Climate Change Anxiety Scale |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Climate Change: Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045125 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Clayton, S. Mental health risk and resilience among climate scientists. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, P.J. Anxiety: Splitting the phenomenological atom. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2011, 50, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions predict policy support: Why it matters how people feel about climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. Social Survey: Climate Change Anxiety Index. 22 February 2023. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mento, C.; Damiani, F.; La Versa, M.; Cedro, C.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Bruno, A.; Fabio, R.A.; Silvestri, M.C. Eco-anxiety: An evolutionary line from psychology to psychopathology. Medicina 2023, 59, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenluft, E.; Allen, L.E.; Althoff, R.R.; Brotman, M.A.; Burke, J.D.; Carlson, G.A.; Stringaris, A. Irritability in youths: A critical integrative review. Am. J. Psychiatry 2024, 181, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchio, D.; Crum, K.I.; Coxe, S.; Pincus, D.B.; Comer, J.S. Irritability and severity of anxious symptomatology among youth with anxiety disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J.; Stringaris, A.; Brotman, M.A.; Montville, D.; Pine, D.S.; Leibenluft, E. Irritability in child and adolescent anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurin, A.; Egloff, B.; Stringaris, A.; Wessa, M. Only complementary voices tell the truth: A reevaluation of validity in multi-informant approaches of child and adolescent clinical assessments. J. Neural Transm. 2016, 123, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel, M.M.; Markon, K.; Smith, G.T. Research review: Multi-informant integration in child and adolescent psychopathology diagnosis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A.; Salas, S.; Menzer, M.M.; Daruwala, S.E. Criterion validity of interpreting scores from multi-informant statistical interactions as measures of informant discrepancies in psychological assessments of children and adolescents. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A.; Augenstein, T.M.; Wang, M.; Thomas, S.A.; Drabick, D.A.; Burgers, D.E.; Rabinowitz, J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 858–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandon, T.J.; Scott, J.G.; Charlson, F.J.; Thomas, H.J. Coping with climate anxiety: Impacts on functioning in Australian adolescents. Aust. Psychol. 2024, 59, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Emotional awareness: On the importance of including emotional aspects in education for sustainable development (ESD). J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M.C.; Tröger, J.; Hamann, K.R.; Loy, L.S.; Reese, G. Anxiety and climate change: A validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. Clim. Change 2021, 168, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, L.A.; Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W. Use of the coping inventory for stressful situations in a clinically depressed sample: Factor structure, personality correlates, and prediction of distress. J. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 59, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Park, K.; Yoon, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, K.-H. A brief online and offline (paper-and-pencil) screening tool for generalized anxiety disorder: The final phase in the development and validation of the mental health screening tool for anxiety disorders (MHS: A). Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 639366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Yoon, S.; Cho, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, K.H. Final validation of the mental health screening tool for depressive disorders: A brief online and offline screening tool for major depressive disorder. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 992068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Chou, C.-P.; Bentler, P.M. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dobriban, E. Permutation methods for factor analysis and PCA. Ann. Stat. 2020, 48, 2824–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, M.G.; Hemming, D.L.; Betts, R.A. Regional temperature and precipitation changes under high-end (≥4 °C) global warming. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total (N = 300) | Adolescents (N = 150) | Adults (N = 150) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.93 (15.18) | 16.61 (1.13) | 41.24 (12.48) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 117 (39.0%) | 56 (37.3%) | 61 (40.7%) |

| Female | 183 (61.0%) | 94 (62.7%) | 89 (59.3%) |

| Final Education Level | |||

| Elementary School | 35 (11.7%) | 35 (23.3%) | - |

| Middle School | 117 (39.0%) | 115 (76.7%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| High School | 27 (9.0%) | - | 27 (18.0%) |

| 2–4 Year College | 108 (36.0%) | - | 108 (72.0%) |

| Master’s or Higher | 13 (4.3%) | - | 13 (8.7%) |

| Item | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted | Standardized Item–Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Perceived threat to safety) | 2.48 (0.92) | 0.94 | 0.54 *** |

| 2 (Perceived threat to earth) | 2.70 (1.06) | 0.94 | 0.47 *** |

| 3 (Perceived destruction) | 2.40 (1.06) | 0.94 | 0.63 *** |

| 4 (Future concerns) | 2.70 (1.06) | 0.94 | 0.43 *** |

| 5 (Uncontrollable worry) | 1.71 (1.22) | 0.94 | 0.74 *** |

| 6 (Search for Climate Change Information in Media) | 1.84 (1.06) | 0.94 | 0.69 *** |

| 7 (Perceived helplessness) | 2.27 (1.08) | 0.94 | 0.68 *** |

| 8 (Perception of severity) | 2.77 (0.99) | 0.94 | 0.46 *** |

| 9 (Thinking about climate change) | 2.34 (1.03) | 0.94 | 0.68 *** |

| 10 (Worry about impact) | 2.54 (0.99) | 0.94 | 0.66 *** |

| 11 (Emotional distress) | 1.10 (1.19) | 0.94 | 0.80 *** |

| 12 (Nightmares) | 0.81 (1.15) | 0.94 | 0.74 *** |

| 13 (Distraction) | 0.88 (1.11) | 0.94 | 0.80 *** |

| 14 (Insomnia) | 0.86 (1.15) | 0.94 | 0.77 *** |

| 15 (Restlessness) | 1.20 (1.24) | 0.94 | 0.80 *** |

| 16 (Irritability) | 0.86 (1.16) | 0.94 | 0.74 *** |

| 17 (Fear of an impending threat) | 1.26 (1.19) | 0.94 | 0.78 *** |

| 18 (Social disruption) | 0.80 (1.11) | 0.94 | 0.72 *** |

| 19 (Impaired performance) | 0.78 (1.18) | 0.94 | 0.71 *** |

| 20 (Others’ feedback on excessive worry) | 0.86 (1.16) | 0.94 | 0.76 *** |

| 21 (Academic/work disruption) | 0.79 (1.18) | 0.94 | 0.74 *** |

| Characteristic | Total (N = 400) | Adolescents (N = 151) | Adults (N = 249) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 32.14 (18.77) | 15.72 (1.11) | 42.10 (17.39) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 201 (50.3%) | 80 (53.0%) | 121 (48.6%) |

| Female | 199 (49.7%) | 71 (47.0%) | 128 (51.4%) |

| Final Education Level | |||

| Elementary School | 66 (16.5%) | 66 (43.7%) | - |

| Middle School | 124 (31.0%) | 85 (56.3%) | 39 (15.7%) |

| High School | 54 (13.5%) | - | 54 (21.7%) |

| 2–4 Year College | 135 (33.8%) | - | 135 (54.2%) |

| Master’s or Higher | 21 (5.3%) | - | 21 (8.4%) |

| Item | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted | Standardized Item–Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Perceived threat to safety) | 2.6 (0.90) | 0.92 | 0.49 *** |

| 3 (Perceived destruction) | 2.5 (1.03) | 0.92 | 0.56 *** |

| 5 (Uncontrollable worry) | 2.1 (1.23) | 0.92 | 0.69 *** |

| 7 (Perceived helplessness) | 2.4 (1.07) | 0.92 | 0.54 *** |

| 10 (Worry about impact) | 2.5 (0.98) | 0.92 | 0.47 *** |

| 11 (Emotional distress) | 1.6 (1.31) | 0.91 | 0.80 *** |

| 12 (Nightmares) | 1.4 (1.34) | 0.91 | 0.83 *** |

| 13 (Distraction) | 1.5 (1.30) | 0.91 | 0.82 *** |

| 14 (Insomnia) | 1.5 (1.36) | 0.91 | 0.84 *** |

| 15 (Restlessness) | 1.6 (1.26) | 0.91 | 0.84 *** |

| 16 (Irritability) | 1.5 (1.30) | 0.91 | 0.82 *** |

| 18 (Social disruption) | 1.4 (1.31) | 0.91 | 0.80 *** |

| 20 (Others’ feedback on excessive worry) | 1.4 (1.33) | 0.91 | 0.80 *** |

| Model Tested | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-factor model | 216.266 *** (64) | 0.960 | 0.951 | 0.077 | 0.071 |

| Item | Standardized Coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 (Functional Impairment) | ||

| 11 | 0.790 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 0.899 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 0.853 | <0.001 |

| 14 | 0.898 | <0.001 |

| 15 | 0.838 | <0.001 |

| 16 | 0.857 | <0.001 |

| 18 | 0.852 | <0.001 |

| 20 | 0.873 | <0.001 |

| Factor 2 (Cognitive Impairment) | ||

| 1 | 0.683 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.630 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 0.702 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 0.653 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 0.647 | <0.001 |

| No | Items |

|---|---|

| 1 | I worry that climate change will threaten people’s safety (e.g., economic, social, physical safety). |

| 2 | I think climate change will destroy what I value most. |

| 3 | Once I start worrying about climate change, I find it hard to stop. |

| 4 | I worry that I might not be able to cope with climate change. |

| 5 | I worry about the impacts of climate change. |

| 6 | I cry when I think about climate change. |

| 7 | I have nightmares about climate change. |

| 8 | Thinking about climate change makes it hard for me to concentrate on what I’m doing. |

| 9 | Thinking about climate change makes it difficult for me to fall asleep. |

| 10 | Thinking about climate change keeps me from feeling comfortable. |

| 11 | Thinking about climate change makes me become easily annoyed or irritated. |

| 12 | My worries about climate change make it hard for me to enjoy time with my family or friends. |

| 13 | People around me say I think about climate change too much. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Jung, S.; Kang, B.; Lee, Y.; Jin, H.-Y.; Choi, K.-H. Toward Sustainable Mental Health: Development and Validation of the Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change (BACC) in South Korea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156671

Kim H, Jung S, Kang B, Lee Y, Jin H-Y, Choi K-H. Toward Sustainable Mental Health: Development and Validation of the Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change (BACC) in South Korea. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156671

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyunjin, Sooyun Jung, Boyoung Kang, Yongjun Lee, Hye-Young Jin, and Kee-Hong Choi. 2025. "Toward Sustainable Mental Health: Development and Validation of the Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change (BACC) in South Korea" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156671

APA StyleKim, H., Jung, S., Kang, B., Lee, Y., Jin, H.-Y., & Choi, K.-H. (2025). Toward Sustainable Mental Health: Development and Validation of the Brief Anxiety Scale for Climate Change (BACC) in South Korea. Sustainability, 17(15), 6671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156671