From Perceived to Measurable: A Fuzzy Logic Index of Authenticity in Rural Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Understanding Authenticity in Rural Tourism

2.2. Measuring Authenticity: Challenges and Emerging Approaches

2.3. Vernacular Heritage and the Romanian Context

2.4. Gaps in the Literature and the Role of Fuzzy Logic

2.5. Building on Fuzzy Logic: Applications in Rural Tourism Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Designing and Conducting the Fuzzy Logic-Based Survey

3.2. Fuzzy-Likert Transformation

3.3. Calculating Importance Scores for Each Criterion

- Sr,c is the defuzzified score for respondent r on criterion c;

- μk(Lr,c) is the membership value for category k (from 1 to 5);

- k corresponds to the linguistic categories: Very Low = 1, …, Very High = 5;

- r = 1 to 214 (respondents), c = 1 to 9 (authenticity criteria).

- is the average defuzzified score for criterion c;

- is the final defuzzified score for respondent r on criterion c;

- N is the total number of respondents (in our case, 214);

- c = 1, …, 9 corresponds to the nine authenticity criteria.

3.4. Normalization and Weight Assignment

- is the normalized weight for criterion i;

- is the average defuzzified score for criterion i.

3.5. Computation of the Authenticity Index

- is the average tourist rating for criterion i;

- is the score given by tourist t to criterion i;

- T is the total number of tourists who evaluated the accommodation.

- AI(Accommodation) is the overall authenticity score for the evaluated rural guesthouse;

- is the score given by tourist t to criterion i;

- is the normalized weight of criterion iii, derived from fuzzy importance scores;

- i = 1, …, 9 covers all nine authenticity criteria.

4. Results and Discussion

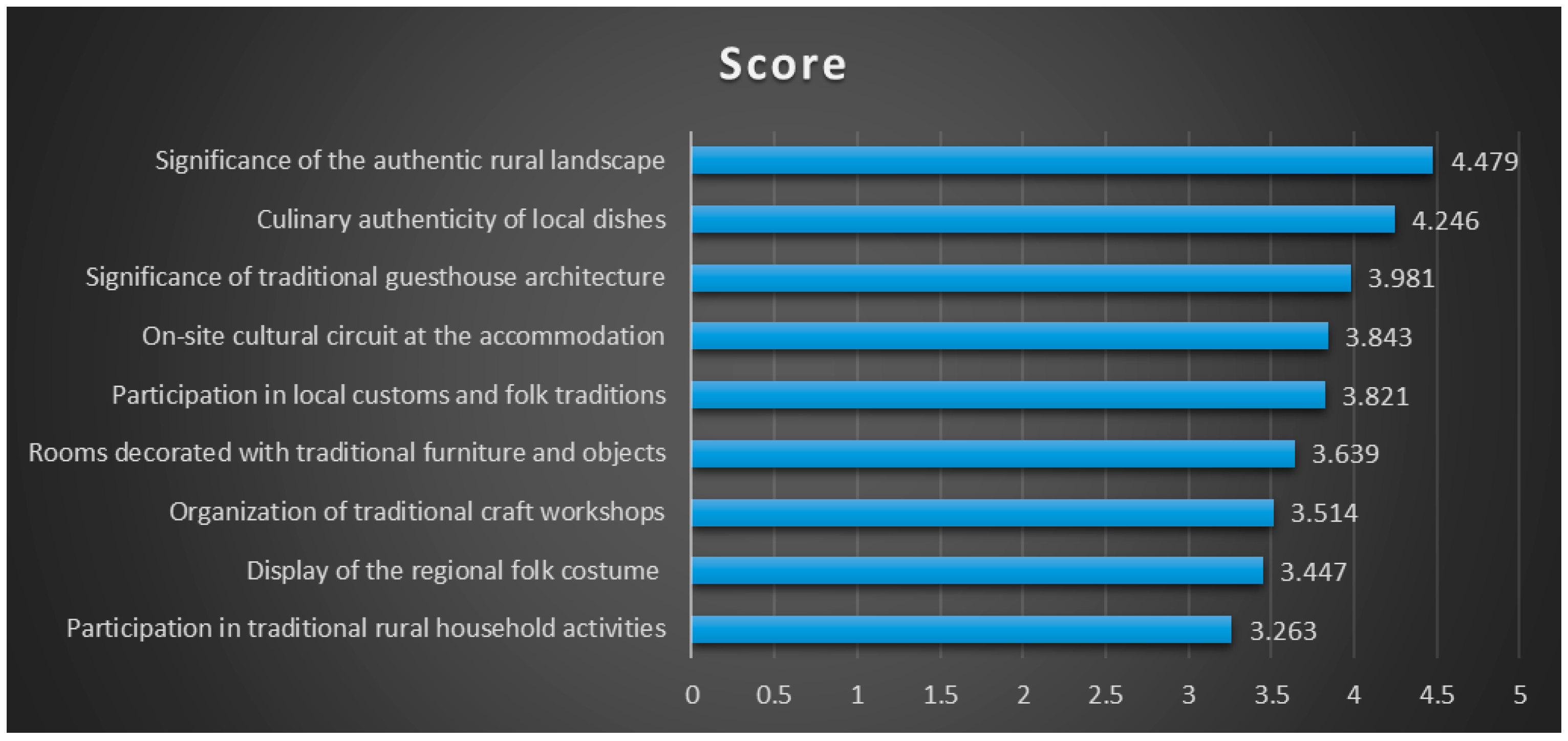

4.1. Descriptive Results for Authenticity Criteria

4.2. Understanding the Weight Distribution

4.3. Interpreting the Authenticity Index Through a Case Scenario

4.4. Practical Implications and Theoretical Reflection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dobre, C.A.; Zaharia, I.; Iorga, A.M. Authenticity in Romanian Rural Tourism—Defining a Concept. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2023, 23, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Dobre, C.A.; Iorga, A.M.; Zaharia, I. Preliminaries on the Agritourism Tourist’s Typology in Romania: Case Study Satul Banului Guesthouse. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 425–430. [Google Scholar]

- Mkono, M. A Netnographic Examination of Constructive Authenticity in Victoria Falls Tourist (Restaurant) Experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food Tourism, Niche Markets and Products in Rural Tourism: Combining the Intimacy Model and the Experience Economy as a Rural Development Strategy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, L.; Pechlaner, H.; Volgger, M. Rural Tourism Development in Mountain Regions: Identifying Success Factors, Challenges and Potentials. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S. Rural Authenticity and Agency on a Cold-Water Island: Perspectives of Contemporary Craft-Artists on Bornholm, Denmark. Shima: Int. J. Res. Isl. Cult. 2016, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, D.; Deng, J.; Maumbe, K. DMOs and Rural Tourism: A Stakeholder Analysis—The Case of Tucker County, West Virginia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, M.; Ristić, L.; Bošković, N. Rural Tourism as a Driver of the Economic and Rural Development in the Republic of Serbia. Menadz. U Hotel. I Tur. 2022, 10, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, A.M.; Dezsi, Ș.; Pop, F.; Cecilia, P. Rural Tourism—Viable Alternatives for Preserving Local Specificity and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study—“Valley of the Kings” (Gurghiului Valley, Mureș County, Romania). Sustainability 2022, 14, 16295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Veljović, S.; Petrović, M.D.; Blešić, I.; Radovanović, M.; Malinović-Milićević, S.; Khamitova, D.M. The Use of Local Ingredients in Shaping Tourist Experience: The Case of Allium ursinum and Revisit Intention in Rural Destinations of Serbia. Foods 2025, 14, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Kong, X.; Chen, P. The Authentic Experiences of Tourists in Chinese Traditional Villages Based on Constructivism: A Case Study of Chengkan Village. Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2023, 5, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Lan, T.; Liu, S.; Zeng, H. The Post-Effects of the Authenticity of Rural Intangible Cultural Heritage and Tourists’ Engagement. Behavavioral Sci. 2024, 14, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleymani, Z.; Qeidari, H.S.; Shayan, H.; Seyfi, S.; Vo-Thanh, T. Enhancing Sustainable Rural Tourism through Memorable Experiences: A Means-End Chain Analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly, J. Existential Authenticity: Place Matters. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Place in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovičová, K. The Triadic Nexus: Understanding the Interplay and Semantic Boundaries Between Place Identity, Place Image, and Place Reputation. Folia Geogr. 2024, 66, 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Apostol, E.M.D.; Villan, M.S.; Jose, T.T.M.; Pasco, K.M.M. Customer Experience (CX) Design in the View of Managers: An Analysis of the Impact of Pandemic in the Local Hospitality and Tourism Industry. Am. J. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 1, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysveen, H.; Oklevik, O.; Pedersen, P.E. Brand Satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2908–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiroglu, O.C.; Turp, M.T.; Kurnaz, M.L.; Abegg, B. The Ski Climate Index (SCI): Fuzzification and a Regional Climate Modeling Application for Turkey. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 65, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, A.; Balbal, K.F. Fuzzy Logic Based Performance Analysis of Educational Mobile Game for Engineering Students. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2020, 28, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Using the Fuzzy Method and Multi-Criteria Decision Making to Analyze the Impact of Digital Economy on Urban Tourism. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săsăran, P.; Țenter, A.; Jianu, L.-D. Cultural Heritage of a Three Centuries Old Wooden Church; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L.; Bădiță, A. Rural Tourism to the Rescue of the Countryside? Oltenia as a Case Study. J. Tour. Chall. Trends 2011, 4, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu, A.; Štetić, S. Rural Tourism in Romania. South Muntenia Region Case Study. In Modern Management Tools and Economy of Tourism Sector in Present Era; Association of Economists and Managers of the Balkans in cooperation with the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality: Belgrade, Serbia; Ohrid, Macedonia, 2016; pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, M.; Popescu, A.; Stanciu, C. Rural Tourism, Agrotourism and Ecotourism in Romania: Current Research Status and Future Trends. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2023, 23, 745–758. [Google Scholar]

- Dobre, C.A.; Iorga, A.M.; Stoicea, P. Authentic Romanian and rural tourism in the Sub-Carpathian Muntenia area: Original case study “Satul Banului Guest House”. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2022, 22, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Preda (Alexe), M.; Mărcuța, L.; Mărcuța, A.; Vasile, A.S.; Stanciu (Onea), M. Development Possibilities of the Hospitality Sector by Creating and Promoting Authentic Tourist Experiences. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. Toward an Understanding of Tourists’ Authentic Heritage Experiences: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2015, 33, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chroneos-Krasavac, B.; Radosavljević, K.; Bradić-Martinović, A. SWOT Analysis of the Rural Tourism as a Channel of Marketing for Agricultural Products in Serbia. Ekon. Poljopr. 2018, 65, 1573–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.; Hanks, L. Consumption Authenticity in the Accommodations Industry: The Keys to Brand Love and Brand Loyalty for Hotels and Airbnb. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Yu, J.; Cheng, Q.; Hai-yin, P. The Influence Mechanism and Measurement of Tourists’ Authenticity Perception on the Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism—A Study Based on the 10 Most Popular Rural Tourism Destinations in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadi, A.I.M.; Mamlook, R.E.A.; Almarhabi, Y.; Ullah, I.; Jamal, A.; Bandara, N. A Fuzzy-Logic Approach Based on Driver Decision-Making Behavior Modeling and Simulation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, A.; Korcsmáros, E. Development Prospects of Rural Tourism Along the Danube. Key Factors of Satisfaction and the Role of Sustainability. Folia Geogr. 2024, 66, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lulcheva, I. Study of the Consumer Interest of Culinary Tourism in Bulgaria. Sci. Papers. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2020, 20, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, G.; Gurbuz, I.B. Quiet and Blessed: Rural Tourism Experience and Visitor Satisfaction in the Shadow of COVID−19 and Beyond. Sci. Papers. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2023, 23, 531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Tenie (Vasile-Tudor), B.; Fîntîneru, G. What Attracts Tourists in Rural Areas? An Analysis of the Key Attributes of Agritourist Destinations That May Influence Their Choice. AgroLife Sci. J. 2020, 324. [Google Scholar]

| Likert Score | Very Low (μVL) | Low (μL) | Medium (μM) | High (μH) | Very High (μVH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| 5 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Criterion | Fuzzy Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low (VL) | Low (L) | Medium (M) | High (H) | Very High (VH) | Total | ||

| 1. Significance of the authentic rural landscape | Sum (k × μ) 1 | 4.00 | 14.50 | 43.50 | 179.00 | 717.50 | 958.50 |

| Percentage (%) 2 | 0.42 | 1.51 | 4.54 | 18.68 | 74.86 | 100.00 | |

| Sum (μ) 3 | 4.00 | 7.25 | 14.40 | 44.75 | 143.50 | 214.00 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) 4 | Criterion Score 4479 | ||||||

| 2. Significance of traditional guesthouse architecture | Sum (k × μ) | 7.50 | 47.00 | 96.00 | 214.00 | 487.50 | 852.00 |

| Percentage (%) | 0.88 | 5.52 | 11.27 | 25.12 | 57.22 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 7.50 | 23.50 | 32.00 | 53.50 | 97.50 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3981 | ||||||

| 3. Rooms decorated with traditional furniture and objects | Sum (k × μ) | 12.25 | 70.50 | 117.00 | 234.00 | 345.00 | 778.75 |

| Percentage (%) | 1.57 | 9.05 | 15.02 | 30.05 | 44.30 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 12.25 | 35.25 | 39.00 | 58.50 | 69.00 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3639 | ||||||

| 4. Culinary authenticity of local dishes | Sum (k × μ) | 6.75 | 33.00 | 49.50 | 207.00 | 612.50 | 908.75 |

| Percentage (%) | 0.74 | 3.63 | 5.45 | 22.78 | 67.40 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 6.75 | 16.50 | 16.50 | 51.75 | 122.50 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 4246 | ||||||

| 5. Participation in local customs and folk traditions | Sum (k × μ) | 15.50 | 51.50 | 73.50 | 256.00 | 421.25 | 817.75 |

| Percentage (%) | 1.90 | 6.30 | 8.99 | 31.31 | 51.51 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 15.50 | 25.75 | 24.50 | 64.00 | 84.25 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3821 | ||||||

| 6. Organization of traditional craft workshops | Sum (k × μ) | 19.50 | 78.00 | 99.00 | 228.00 | 327.50 | 752.00 |

| Percentage (%) | 2.59 | 10.37 | 13.16 | 30.32 | 43.55 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 19.50 | 39.00 | 33.00 | 57.00 | 65.50 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3514 | ||||||

| 7. Participation in traditional rural household activities | Sum (k × μ) | 33.00 | 84.50 | 91.50 | 208.00 | 281.25 | 698.25 |

| Percentage (%) | 4.73 | 12.10 | 13.10 | 29.79 | 40.28 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 33.00 | 42.25 | 30.50 | 52.00 | 56.25 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3263 | ||||||

| 8. Display of the regional folk costume | Sum (k × μ) | 24.75 | 78.00 | 94.50 | 213.00 | 327.50 | 737.75 |

| Percentage (%) | 3.35 | 10.57 | 12.81 | 28.87 | 44.39 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 24.75 | 39.00 | 31.50 | 53.25 | 65.50 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3447 | ||||||

| 9. On-site cultural circuit at the accommodation | Sum (k × μ) | 12.75 | 57.00 | 85.50 | 216.00 | 451.25 | 822.50 |

| Percentage (%) | 1.55 | 6.93 | 10.40 | 26.26 | 54.86 | 100.0 | |

| Sum (μ) | 12.75 | 28.50 | 28.50 | 54.00 | 90.25 | 214.0 | |

| Sum (k × μ)/Sum (μ) | Criterion Score 3843 | ||||||

| Criterion | Score | Weight (wᵢ) |

|---|---|---|

| 4.479 | 0.131 |

| 3.981 | 0.116 |

| 3.639 | 0.106 |

| 4.246 | 0.124 |

| 3.821 | 0.112 |

| 3.514 | 0.103 |

| 3.263 | 0.095 |

| 3.447 | 0.101 |

| 3.843 | 0.112 |

| TOTAL | 34.235 | 1.000 |

| Criterion No. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accomodation A | Turist | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | Index |

| 1 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8.4 | |

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||

| 3 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Average | 7.67 | 8.00 | 8.67 | 8.67 | 9.67 | 7.33 | 7.33 | 7.67 | 9.67 | ||

| Weight | 0.131 | 0.116 | 0.106 | 0.124 | 0.112 | 0.103 | 0.095 | 0.101 | 0.112 | ||

| Average × Weight | 1.003 | 0.930 | 0.921 | 1.075 | 1.079 | 0.753 | 0.699 | 0.772 | 1.085 | ||

| Criterion No. | |||||||||||

| Accomodation B | Turist | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | Index |

| 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4.7 | |

| 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Average | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 5.33 | 4.67 | 4.33 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.67 | ||

| Weight | 0.129 | 0.114 | 0.106 | 0.122 | 0.111 | 0.104 | 0.100 | 0.103 | 0.112 | ||

| Average × Weight | 0.611 | 0.543 | 0.496 | 0.662 | 0.521 | 0.445 | 0.445 | 0.470 | 0.524 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobre, C.; Toma, E.; Linca, A.-C.; Iorga, A.M.; Zaharia, I.; Fintineru, G.; Stoicea, P.; Chiurciu, I. From Perceived to Measurable: A Fuzzy Logic Index of Authenticity in Rural Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156667

Dobre C, Toma E, Linca A-C, Iorga AM, Zaharia I, Fintineru G, Stoicea P, Chiurciu I. From Perceived to Measurable: A Fuzzy Logic Index of Authenticity in Rural Tourism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156667

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobre, Carina, Elena Toma, Andreea-Cristiana Linca, Adina Magdalena Iorga, Iuliana Zaharia, Gina Fintineru, Paula Stoicea, and Irina Chiurciu. 2025. "From Perceived to Measurable: A Fuzzy Logic Index of Authenticity in Rural Tourism" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156667

APA StyleDobre, C., Toma, E., Linca, A.-C., Iorga, A. M., Zaharia, I., Fintineru, G., Stoicea, P., & Chiurciu, I. (2025). From Perceived to Measurable: A Fuzzy Logic Index of Authenticity in Rural Tourism. Sustainability, 17(15), 6667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156667