3.1. Study Area

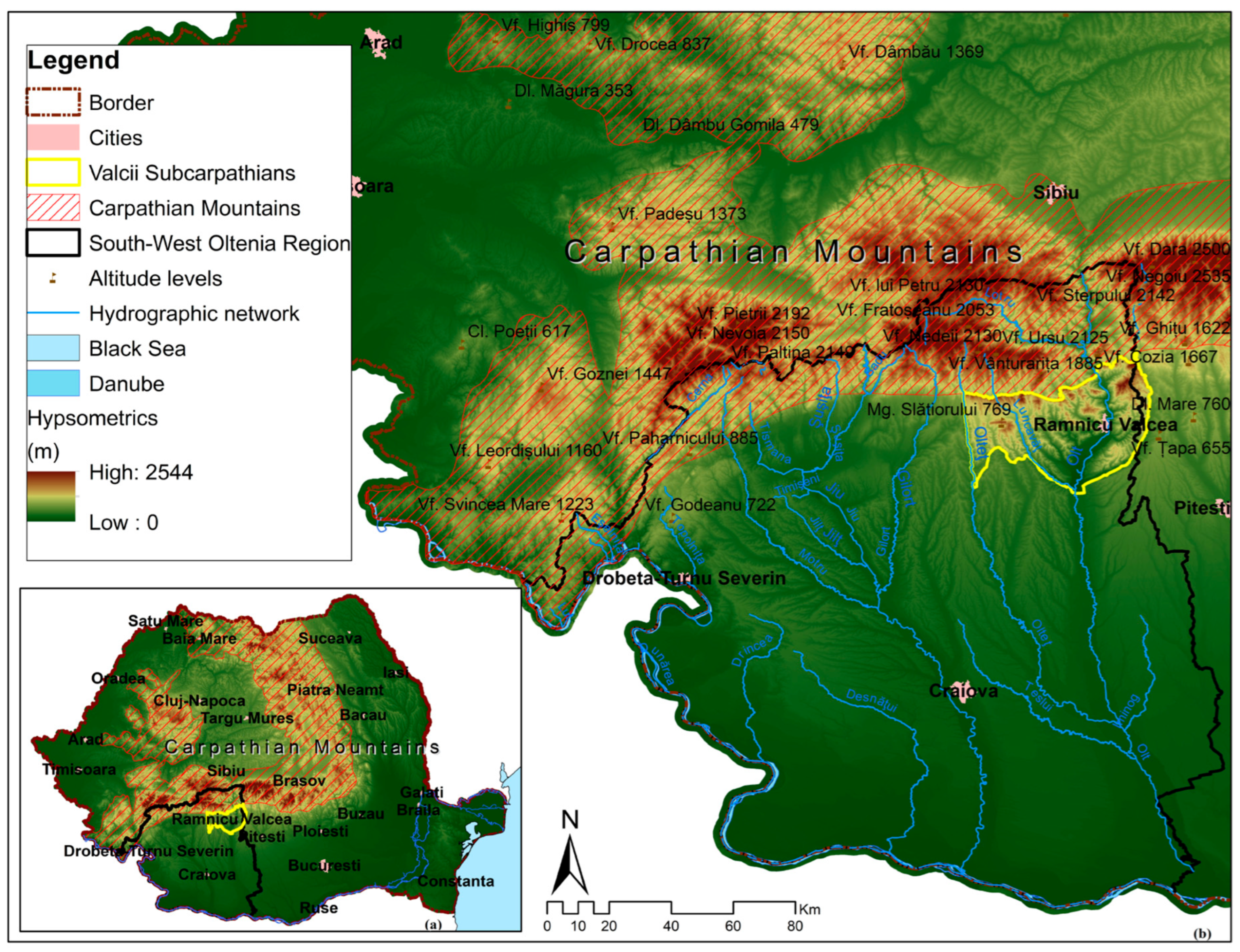

A subdivision of the Getic Subcarpathians, the Vâlcea Subcarpathians are located in the southern part of the country, on both sides of the Olt River, and constitute one of the oldest settlements in Romania. Thus, in

Figure 1, the study area is mapped, with the location of the Vâlcea Subcarpathians in regional (

Figure 1a and national contexts (

Figure 1b. Mentioned in documents written as early as January 1392, in a charter of Mircea the Elder, the Vâlcea study area appears as a relief step between the mountains and the lowlands outside them, being made up of an association of hilly peaks separated by valleys or depressions ([

67], p. 51).

According to Roșu (1980) ([

68], pp. 389–390), the Vâlcea Subcarpathians are located “between Bistrița Vâlcii and Gilort, corresponding to the area of the subcarpathian folds. They are made up of a single subcarpathian corridor: Hurez-Polovragi-Novaci and a single row of subcarpathian hills: Măgura Slătioarei (267 m), Dealul Grecilor (594 m), Dealul Muierii (561 m), Dealul Cîrligeilor (536 m), Dealul Seciului (597 m). The subcarpathian contact with the Getic Plateau in the south is achieved through a depressional erosion corridor: Matești-Becheni-Zorlești, with the exception of the tectonic Zorlești Depression, which is located at the beginning of the external subcarpathian depressional corridor in the west of Gilort, Cărbunești-Târgu Jiu” [

68].

According to Ielenicz et al. (2003) ([

69], p. 214), the Vâlcea Subcarpathians “extend from Topolog to Bistrița, east of Olt, under the steeps of the Cozia Mountains, there is a wider Jiblea depression through which connections are made with Țara Loviștei, west of Olt, it continues with several depression basins (the most significant are Muereasca, Olănești, Bărbătești, etc.) in which there are villages specialized in animal husbandry. To the south, where the folded structure on several anticlines and synclines clearly appears, small depressions (Govora, Ocnele Mari) have developed in the soft rocks as a result of differential erosion (especially at the contact with the Getic Plateau)” [

69].

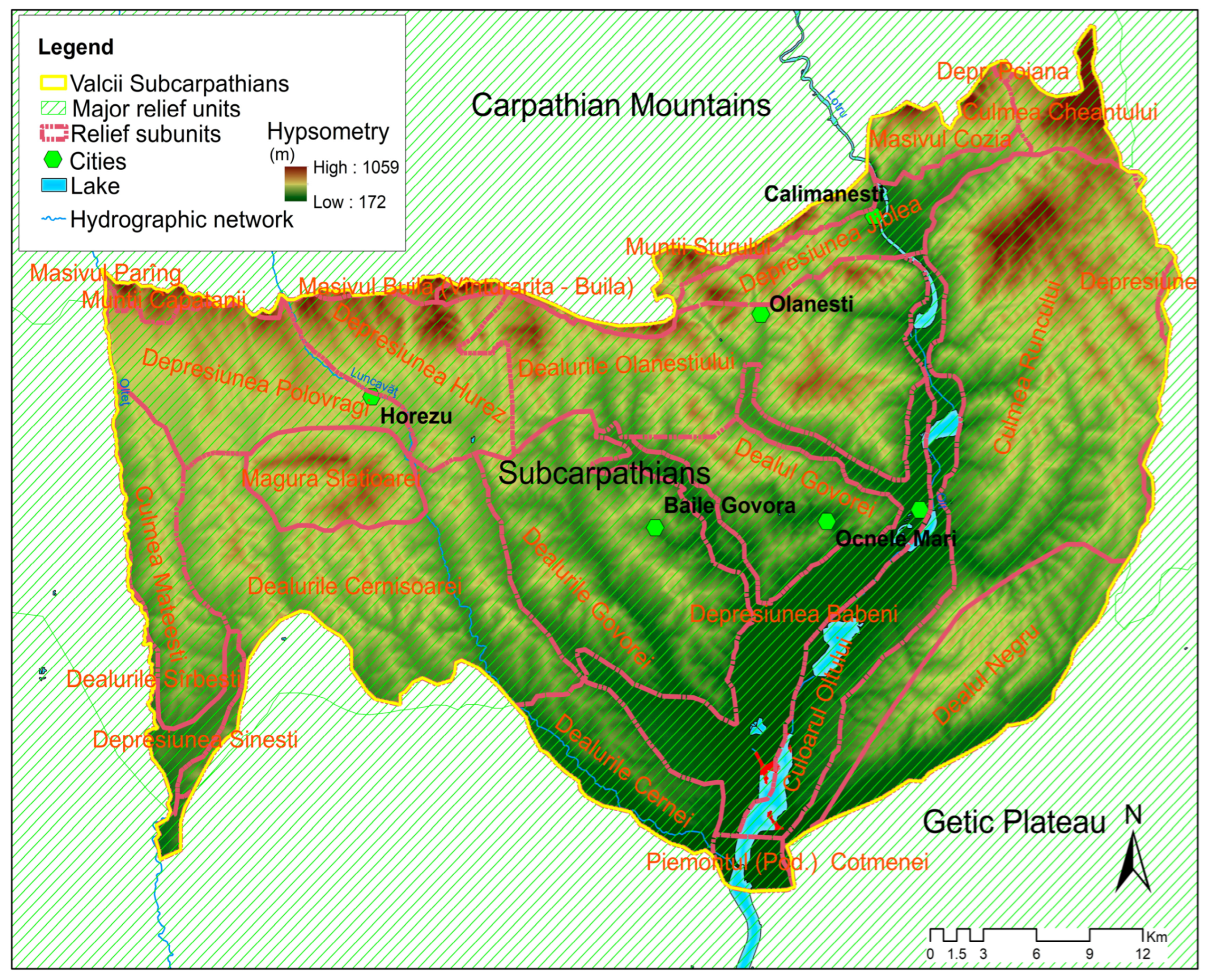

In addition to the specific limits of the natural environment [

70], such as relief steps, hypsometry, and hydrographic network (

Figure 2), we encounter in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians the anthropogenic limits resulting from the administrative–territorial division (

Figure 3), which mainly includes Vâlcea County and a small part of Argeș and Gorj Counties ([

67] p. 53). Thus, the study area includes 1 municipality, 7 towns, and 45 communes.

The climate of the Vâlcea Subcarpathians is also greatly influenced by their position, by their location under the shelter of the Southern Carpathians, and implicitly by the forested mountains from which fresh waves of cold air descend in the summer, as well as by the Olt valley, which carries cold, snowy air in the winter. It is also under the influence of the depressions located on both sides of the river, which provide mild shade against both the winter frost and summer heat. Therefore, the area has a temperate continental climate influenced by the difference in the 300–500 m height level in the south and the valley corridors in the north–south direction ([

67], p. 69).

The current hydrographic network draining the Vâlcea Subcarpathians belongs to the Olt basin. The rivers in the west are oriented north–south; however, due to a slight tectonic depression, the rivers in the Vâlcea area are diverted to the southeast near the Olt. This inclination is also highlighted by a gradual and general decrease in altitude from west to east.

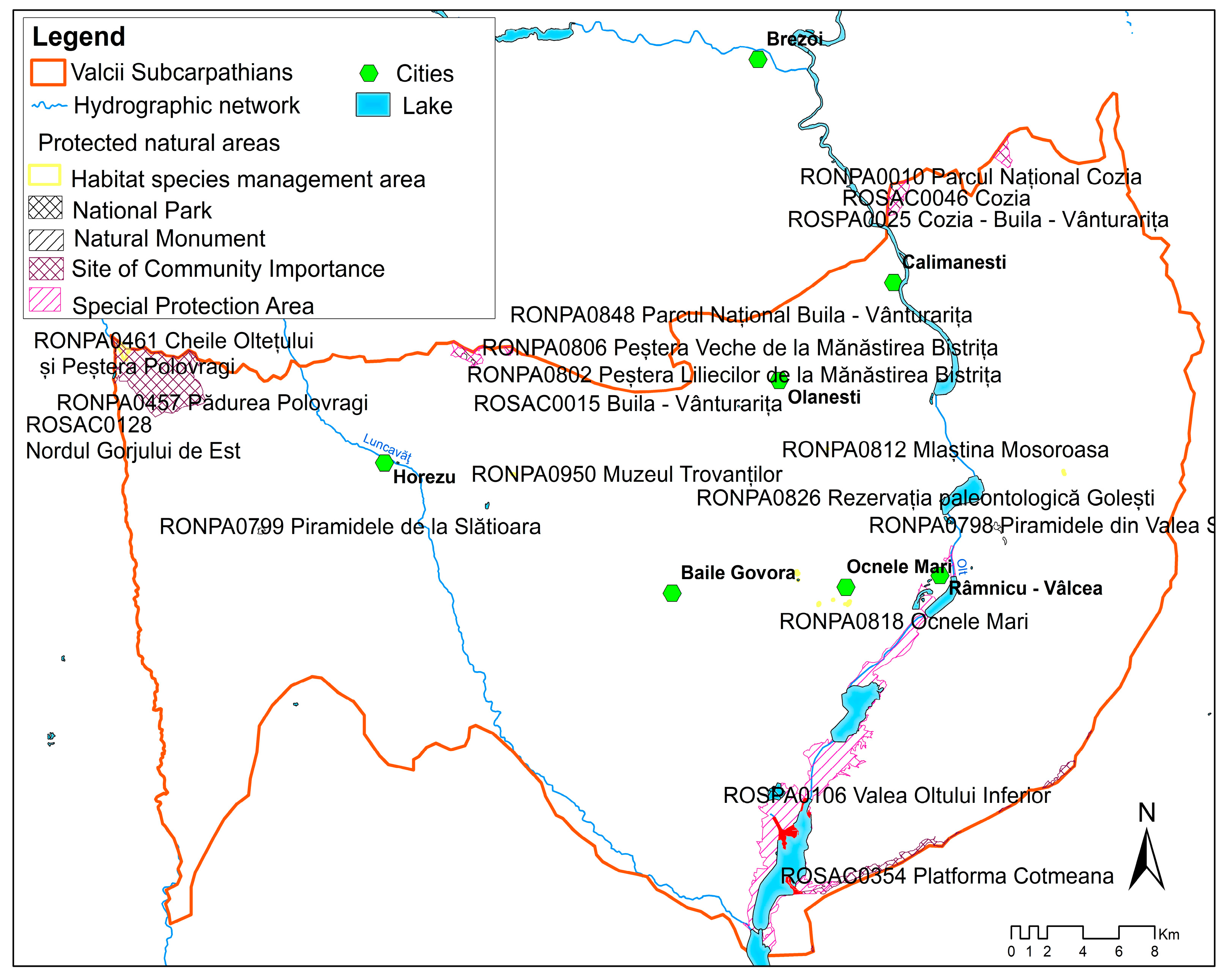

Nature reserves represent a determining point in clarifying the biopedogeographic conditions that characterize the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, constituting a point of attraction for visitors and foreign tourists. These include the Pyramids on Valea Stăncioiului Geomorphological Reserve, the Mosoroasa Swamp Nature Reserve, the Golești Paleontological Reserve, the Trovanții from Costești, Cozia National Park, Buila-Vânturarița National Park, Olteț Gorges, Ocnele Mari Reserve, Liliecilor Cave, etc. (

Figure 4).

Enhancing tourist attractions, i.e., protected areas/natural reserves in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians (

Figure 4), would increase interest in spa tourism, rural tourism, agrotourism, ecotourism, and geotourism, and offer an opportunity for economic activity through the development of new jobs, thus decreasing unemployment in the study area.

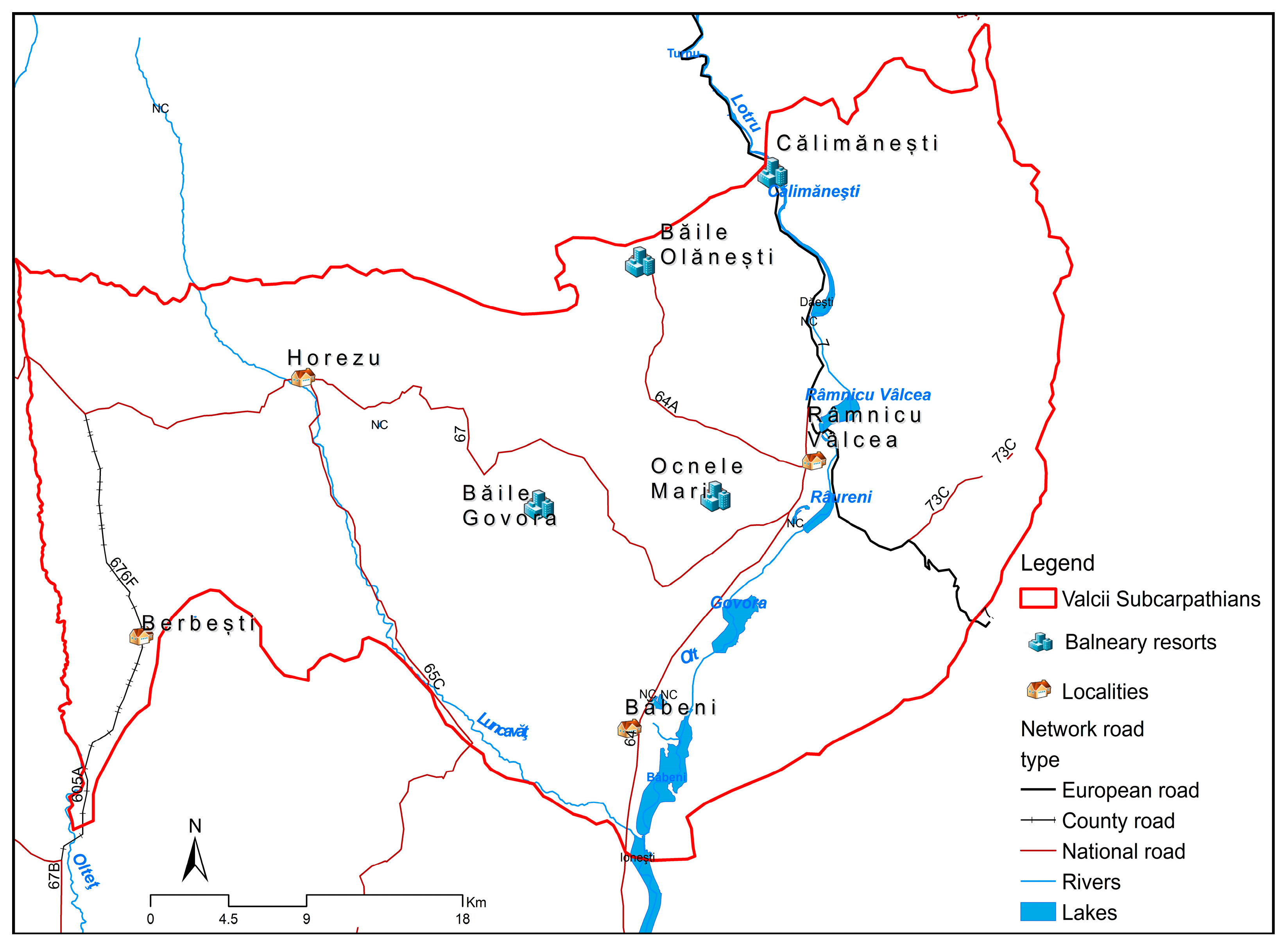

The spa resorts included in the research are shown in

Figure 5: Băile Olănești, Călimănești, Băile Govora, and Ocnele Mari.

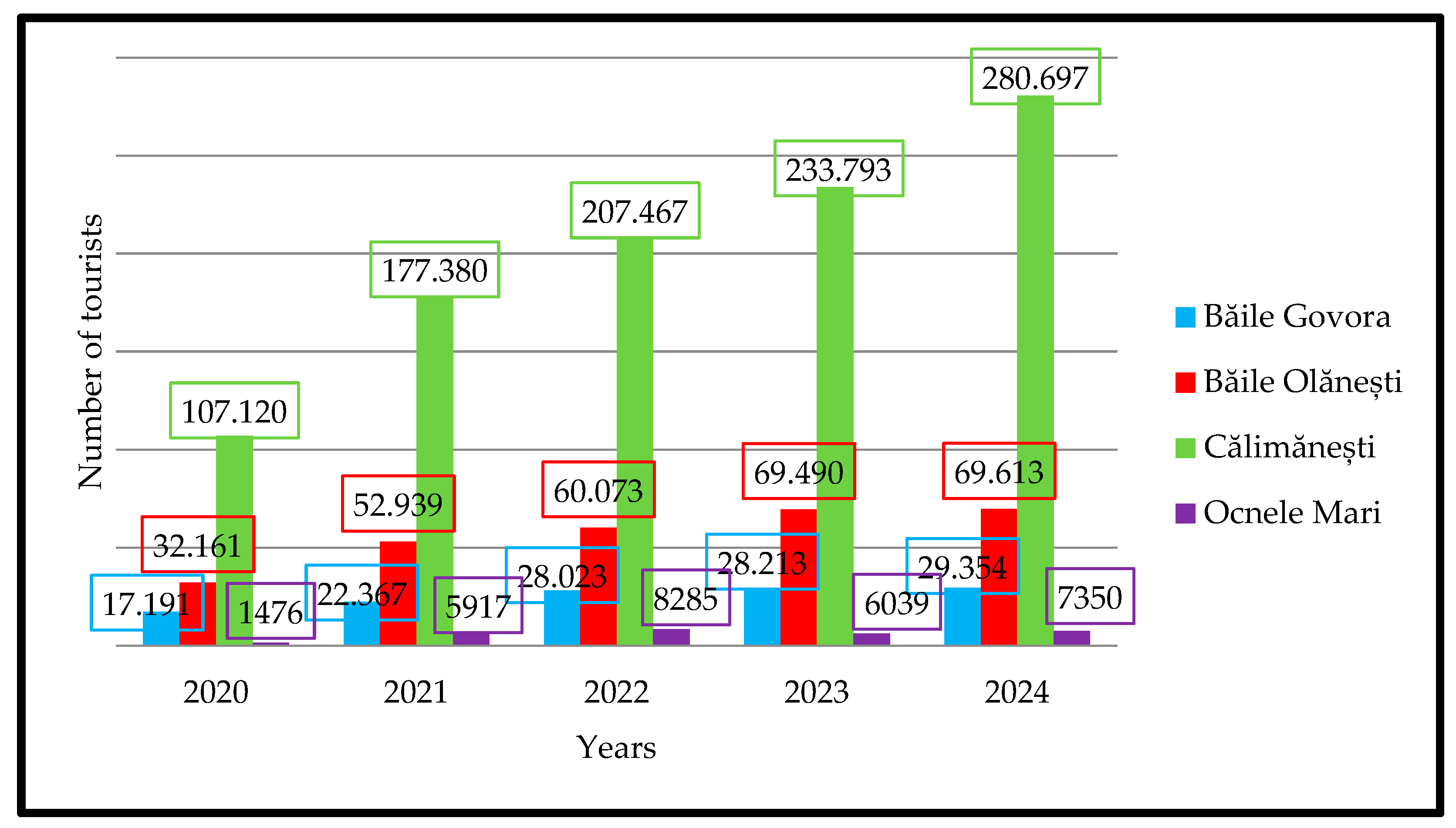

Analyzing statistical data from the National Institute of Statistics (NIS) for 2020–2024 [

71], we observe increases in the number of tourists arriving at the spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians (

Figure 6). Thus, despite the pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), tourists chose in quite large numbers to spend their holidays at these spa resorts, and at the same time, to benefit from health care treatments that were considered to be possible prevention against COVID-19.

The Călimănești spa resort recorded 107,120 tourists in 2020, followed by an upward trend in subsequent years, reaching 280,697 tourists in 2024—more than double the initial figure (

Figure 6). A similar trend can be observed at the Băile Olănești resort, which registered 32,161 tourists in 2020; by 2024, this number had more than doubled, exceeding 69,000 visitors. Among the four spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, Ocnele Mari reported the lowest total number of tourists during the 2020–2024 period, with only 29,067 visitors.

3.2. Data Sources

To locate the study area, the specific boundaries of the natural environment: relief units and subunits, hypsometry, hydrography, spa resorts and reserves/protected areas in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, the authors used the Geographic Information System (GIS) which allowed them to process, store, manipulate, analyze and visualize the data, and in the final phase they produced physical-geographic maps based on this data.

A questionnaire was used to assess the motivation of tourists visiting spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

To ensure the survey data were accurate and reliable, the respondents recruited for this research were all Vâlcea Subcarpathian tourists. The questionnaire consisted of two sections: the first was dedicated to the collection of sociodemographic data on the tourists, and the second was for the collection of data on the main research objectives. The questionnaire collected several types of data: dichotomous, semantic scale, closed, demographic (sex, age and profession), semi-open and opinion.

The data collection phase took place between February and June 2024. The data were collected by administering the questionnaire through social media networks. In total, 556 questionnaires were completed, and 522 valid questionnaires remained after cleaning up the data. The selected sample size was considered statistically adequate to produce reliable results and to rigorously evaluate the associations among the study variables. Random sampling was employed to mitigate selection bias, thereby enhancing the objectivity and representativeness of the collected data. The following preamble was included in the questionnaire: “All data collected are confidential and will be used strictly for academic purposes.”

The data cleaning process involved removing questionnaires that were partially completed, contained inconsistent or uniform responses (indicating low engagement) or were submitted by individuals not belonging to the target population (e.g., those under the age of 18). All tourists were invited to participate voluntarily, and only adults (18 years and older) were included in the final sample.

The data were organized and presented using Microsoft Office 2010, facilitating the creation of the tables and graphs necessary to clearly illustrate the results. To analyze the data collected and test the hypotheses formulated in this research, the following statistical methods were used: Chi-Square Test, Independent Samples t-Test, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). These methods are described in detail below, along with the associated formulas and relevant bibliographic sources.

3.2.1. Chi-Square Test

The Chi-Square Test is used to test the association between two nominal or ordinal variables, and is an essential tool in the analysis of categorical data. In the present research, this test was applied to analyze the relationships between variables such as frequency of visits and perception of main attractions [

72].

The formula for the Chi-Square test is [

73]:

where

represents the observed frequencies;

represents the expected frequencies calculated based on the assumption of independence [

74].

The Chi-square test assesses whether the distribution of responses to one variable is independent of the distribution of responses to the other variable. A significant Chi-square test indicates an association between the two variables, suggesting that the distributions are not independent [

75].

3.2.2. Independent Samples t-Test

The Independent Samples t-Test is a statistical method used to determine whether there is a significant difference between the means of two independent groups. This test is useful in situations where we want to compare two sets of data to see if the observed differences are due to chance or if they are statistically significant.

The test assumes that the data from both groups are normally distributed and that the variances of the two groups are equal. The test compares the means of two groups to see if the difference between them is large enough not to be attributed to chance [

76,

77,

78].

The basic formula for calculating the

t-value of independent samples is [

79]:

where

and are the means of the two groups;

and are the sample variances;

and are the sample sizes.

To determine whether the values of the variable have equal variances or not, the Levene test can be used. If the variances are not equal, an adjusted variant of the t-test known as the Welch’s t-test is used.

3.2.3. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is a statistical technique used to compare the means of three or more groups to see if there are significant differences between them. ANOVA is essential in statistical analyses involving multiple groups, providing a robust method for assessing variability and identifying factors that may influence the results [

80,

81].

ANOVA tests the null hypothesis that all groups have equal means. If the null hypothesis is rejected, it is concluded that at least one of the groups has a different mean from the others. ANOVA can be used in a variety of contexts, such as controlled experiments, observational studies and market research.

The basic formula for one-way ANOVA is [

82]:

where

MSB is the mean of squares between groups, calculated as the sum of squares between groups (SSB) divided by the degrees of freedom between groups ();

MSW is the mean of squares within groups, calculated as the sum of squares within groups (SSW) divided by the degrees of freedom within groups ().

3.3. Analyzing Research Questions and Formulating Research Hypotheses

The formulation of hypotheses is based on the literature and previous observations, providing a theoretical framework to guide subsequent statistical analysis.

This approach aims to establish a clear link between the research questions and the hypotheses tested, thus ensuring their validity and relevance. Each hypothesis is developed in the specific context of spa resorts, taking into account the particularities and preferences of tourists, as well as the factors that may influence their behavior. Thus, a deeper understanding of the phenomena investigated is facilitated, and the necessary foundation is provided for the interpretation of the results obtained in the research.

RQ1: How does the age range of tourists influence the frequency of visits to the spa resorts of the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

Previous studies suggest that different age groups have distinct tourist behaviors. For example, young people may have a higher frequency of visits due to greater flexibility and availability of free time, while older people may prefer less frequent but longer visits. Pearce (1988) highlighted that age is a significant factor in tourist behavior, with young people tending to travel more frequently for recreation, and older people seeking more relaxing and longer experiences [

83]. These observations led to the formulation of the hypothesis that the age of tourists influences the frequency of visits.

H1. There is a significant relationship between the age of tourists and the frequency of visits to the spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

This hypothesis is adapted from the research of Pearce (1988), which uses scales to measure tourist behavior according to age [

83]. Pearce developed a hierarchical model of tourist needs that shows that tourist motivations and behaviors evolve with age and experience.

This reasoning is based on the idea that demographic variables, such as age, significantly influence tourist behaviors and preferences, thus justifying hypothesis H1.

The formulation of hypotheses is based on the literature and previous observations, providing a theoretical framework to guide subsequent statistical analysis.

This approach aims to establish a clear link between the research questions and the hypotheses tested, thus ensuring their validity and relevance. Each hypothesis is developed in the specific context of the spa resorts, taking into account the particularities and preferences of tourists, as well as the factors that may influence their behavior. Thus, a deeper understanding of the phenomena investigated is facilitated, and the necessary foundation is provided for the interpretation of the results obtained in the research.

RQ2: Are there significant differences in the perception of service quality at the spa resorts of the Vâlcea Subcarpathians between men and women?

The specialized literature indicates that there are differences in perception between men and women regarding the quality of tourist services. Women may pay more attention to details related to cleanliness and comfort. Mattila (1999) highlighted these differences, emphasizing that the gender of tourists influences the perception of service quality [

84]. These observations led to the formulation of the hypothesis that the gender of tourists influences the perception of service quality.

H2. The perception of service quality at spa resorts differs significantly according to the gender of tourists.

The hypothesis is inspired by validated scales measuring service satisfaction, such as SERVQUAL [

85], adapted to include the gender variable. SERVQUAL is a recognized tool for assessing service quality by measuring five main dimensions: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. The application of this gender-adapted model allows for a detailed analysis of how men’s and women’s perceptions of service quality may differ, thus justifying hypothesis H2.

This hypothesis is based on the idea that demographic variables, such as gender, can significantly influence the way in which tourism services are perceived, thus providing a solid theoretical framework for the statistical analysis.

RQ3: How does the level of education of tourists influence the information sources used to plan visits to the spa resorts of the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

Studies show that tourists with a higher level of education tend to use more diverse and reliable information sources, such as academic articles or detailed online reviews. These tourists are more likely to seek out information from multiple sources to plan their trips, which represents more sophisticated information behavior [

86]. Existing observations and research emphasize the importance of the level of education in determining the information behavior of tourists, suggesting that they adopt different information search strategies depending on their education.

H3. The level of education of tourists significantly influences the information sources used to plan visits to spa resorts.

The hypothesis is formulated based on research investigating information behavior in tourism, using validated scales measuring information sources [

87]. Studies by Buhalis and Law have demonstrated that tourists with a higher level of education are more inclined to use complex and varied information sources to plan their trips. This is due to their ability to evaluate and critically analyze the available information, ensuring that it is reliable and relevant to their specific needs.

This hypothesis emphasizes the importance of the level of education in shaping tourists’ information behavior and suggests that education may play a crucial role in how they access and use information to plan their visits to spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

RQ4: How is the labor market status of tourists associated with the average duration of trips to the Vâlcea Subcarpathian spa resorts?

People with different labor market status (e.g., employees vs. retirees) have different patterns of tourism behavior. Employees may make shorter trips due to time constraints, while retirees with more free time may book longer trips. Studies by Oppermann (1995) have shown that there is a significant correlation between labor market status and tourism behavior, highlighting that professional status influences the duration and frequency of trips [

88].

H4. Tourists’ labor market status is associated with the average duration of trips to the spa resorts of the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

The hypothesis is based on studies of travel behavior related to labor market status [

88], adapted to the spa context. Oppermann demonstrated that people with different labor market statuses, such as employees and retirees, show significant differences in their travel behavior. Employees, due to constraints related to their job and work schedule, tend to plan shorter and more frequent trips compared to retirees, who have more free time and can opt for longer stays.

These observations were measured using validated scales to assess the duration and frequency of trips according to the professional status of tourists. Oppermann’s research has highlighted the importance of understanding how professional status influences tourist preferences and behaviors, thus providing a theoretical framework to investigate these differences in the context of spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

RQ5: How does the frequency of visits to spa resorts vary depending on the residential environment of tourists in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

Studies and observations in tourism suggest that the residential environment (urban or rural) of tourists can influence the frequency of visits to spa resorts. Tourists from urban areas may tend to visit spa resorts more frequently due to greater accessibility and a desire to escape the crowded urban environment. In contrast, tourists from rural areas may have other priorities or constraints that influence their frequency of visits.

H5. There is a significant difference between the area of residence of tourists and the frequency of visits to spa resorts.

People from urban and rural areas have different patterns of tourist behavior. Urban residents may visit spa resorts more frequently due to easier access to information and greater financial resources, while rural residents may make less frequent visits due to financial constraints and limited access.

A study by Smith and Puczkó (2009) highlights the fact that the area of residence influences the frequency of travel [

89]. These authors demonstrated that urban residents are more likely to travel frequently for recreation and relaxation, due to the stress associated with urban life and easier access to tourist infrastructure [

89]. In contrast, rural residents may have economic and access constraints that limit the frequency of their travel.

This hypothesis is based on studies of travel behavior related to the environment of residence [

89], adapted to the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure the frequency of travel according to the environment of residence of tourists, highlighting the significant influence of this factor on tourist behavior.

RQ6: Are there differences in the frequency of visits to the spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians between tourists who have previously visited and those who are visiting for the first time?

The literature indicates that previous visiting experience can influence tourist behavior and the frequency of visits. Tourists who have previously visited spa resorts may be more inclined to visit them again, due to satisfaction and familiarity with the services offered.

H6. There is a significant difference in the frequency of visits to the spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians between tourists who have previously visited these resorts and those who are visiting them for the first time.

Tourists who have previously visited spa resorts are more likely to return due to familiarity with the location and satisfaction with previous visits. On the other hand, tourists who are visiting for the first time may have a lower frequency of visits due to a lack of knowledge and experience.

A study by Kozak (2001) highlighted the fact that previous experience influences the decision to return [

90]. Kozak emphasized that tourists satisfied with previous visits tend to repeat the experience, while those who have not visited the destination before are influenced by perceptions and recommendations.

The hypothesis is based on studies of travel behavior related to previous experience [

90], adapted to the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure visit frequency and highlighted the significant impact of previous experience on the decision to return to the same tourist destination.

RQ7: How does the residential environment of tourists influence why they choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

The specialist literature and previous studies show that the residential environment (urban or rural) can influence tourist behaviors and motivations.

For example, tourists from urban areas may be motivated to visit the Subcarpathians to escape the city crowds and enjoy the tranquility and natural beauty of the spa resorts.

On the other hand, tourists from rural areas could be attracted by the modern facilities and the diversified tourist services available in these resorts.

H7. Tourists’ residential environment influences their reasons for choosing to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

Urban and rural tourists may have different reasons for visiting the spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians. For example, urban tourists may seek relaxation and escape from the hustle and bustle of the city, while rural tourists may be more interested in spa treatments and recovery.

A study by Bieger and Laesser (2002) highlighted that the residential environment influences tourist preferences and behaviors [

91].

The hypothesis is based on studies of tourist behavior related to residential environment [

91], adapted for the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure travel motives according to tourists’ residential environment.

RQ8: Is there an association between the frequency of visits to spa resorts and participation in cultural activities?

Studies indicate that participation in cultural activities can increase the frequency of visits because they add value to the tourist experience. These observations have led to the hypothesis that the frequency of visits is associated with participation in cultural activities.

H8. The frequency of visits to spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians is associated with participation in cultural activities.

Studies indicate that participation in cultural activities can increase the frequency of visits, as they add value to the tourist experience. Richards (1996) emphasized that cultural activities are an important factor in attracting tourists and improving their satisfaction [

92]. Cultural activities can diversify the tourist offerings and create additional reasons for repeat visits, thus contributing to a higher frequency of visits.

The hypothesis is based on research measuring the impact of cultural activities on travel behavior, using validated scales [

93]. This research has demonstrated that involvement in cultural activities is associated with more active tourist behavior and with an increased frequency of visits.

RQ9: How does the average travel time in spa resorts vary depending on the means of transport used?

The means of transport can influence the duration of trips. For example, tourists who use public transport may have shorter trips compared to those who use private transport. These observations led to the hypothesis that the average travel time differs depending on the means of transport used.

H9. The average duration of trips to the spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians differs significantly depending on the means of transport used.

The means of transport can influence the duration of trips. For example, tourists using public transport may have shorter trips compared to those using private transport. Lohmann and Duval (2011) highlighted that the accessibility and comfort of the means of transport can determine the length of stay of tourists at the destination [

94]. Private transport, such as personal cars, can offer more flexibility and comfort, encouraging longer stays, while public transport, which may have constraints related to schedule and comfort, can lead to shorter stays.

The hypothesis is formulated based on research on the impact of means of transport on tourist behavior [

94]. This research used validated scales to assess the influence of means of transport on the duration and frequency of trips, highlighting significant differences determined by the type of transport used.

RQ10: How do the information sources used influence why tourists choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

Information sources play a crucial role in the decision-making process of tourists. Various studies show that information accessed via the Internet, recommendations from friends and family, tourist guides and advertising materials can significantly influence tourists’ choice to visit certain destinations. For example, tourists who use online information sources, such as reviews and travel blogs, may be motivated by aspects such as innovation and the unique experiences offered by Vâlcea Subcarpathians. On the other hand, those who rely on personal recommendations or traditional guides may seek relaxation and comfort.

H10. The information sources used influence why tourists choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

The information sources used by tourists may play a crucial role in determining why they choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians. For example, tourists who use travel guides or specialized websites may be motivated by an interest in cultural activities and tourist attractions, while those who rely on personal recommendations may seek more relaxation and spa treatments.

Studies conducted by Gursoy and McCleary (2004) have shown that there is a significant correlation between information sources and travel decisions, highlighting that the type of information accessed influences tourist decisions and preferences [

95].

This hypothesis is based on studies of tourist behavior related to information sources used [

95], adapted for the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure travel motives based on the information sources accessed by tourists.

RQ11: How does the method of vacation planning influence the reasons why tourists choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

The method of vacation planning (self-guided or through travel agencies) can significantly influence why tourists choose to visit a particular destination. Studies show that tourists who plan their vacations on their own tend to be more adventurous and seek personalized experiences, while those who use travel agencies may prefer convenience and all-inclusive packages.

In the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, these differences in planning methods may reflect varied reasons for visiting, from the desire to explore local nature and culture to the search for spa treatments and well-organized relaxation services.

H11. The vacation planning method influences why tourists choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians.

The vacation planning method can significantly influence why tourists choose to visit the Vâlcea Subcarpathians. For example, tourists who plan their vacations through travel agencies may be more oriented towards comfort and all-inclusive facilities, while those who plan on their own might be motivated by exploration and adventure.

Studies by Seabra et al. (2007) have demonstrated that there is a correlation between the vacation planning method and travel motives [

96]. They showed that tourists who use travel agencies tend to seek security and comfort, while independent tourists are often motivated by the freedom and flexibility of their own planning.

This hypothesis is based on research related to tourist behavior and vacation planning methods [

96], adapted for the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure travel motives according to the vacation planning method.

RQ12: How does the reason for visiting influence the frequency of visits to spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

The reason for visiting can have a significant impact on the frequency of visits to spa resorts. Tourists visiting for medical or spa treatments may have a higher frequency of visits due to the need for ongoing treatment.

On the other hand, tourists visiting for relaxation or recreation may make less frequent but longer visits. In the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, these differences in reasons for visiting may reflect different tourist behaviors and preferences, thus influencing the frequency with which they return to spa resorts.

H12. The reason for visiting spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians influences the frequency of visits.

The reason why tourists choose to visit spa resorts can have a significant impact on the frequency of these visits. For example, tourists who come for medical treatments or for relaxation and recovery may make more frequent visits compared to those who visit occasionally for special events or exploration.

Studies by Kozak (2002) have shown that there is a correlation between travel reasons and frequency of visits [

97]. These studies have demonstrated that tourists motivated by health and wellness tend to make more regular and frequent visits to spa destinations, while recreation and exploration are associated with more sporadic visits.

This hypothesis is based on research related to tourist behavior and travel reasons [

97], adapted to the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure the frequency of visits according to travel reasons.

RQ13: Is there an association between participation in cultural activities and the average trip duration to spa resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians?

Participation in cultural activities, such as festivals, local events, museum visits and traditional crafts, can influence the average duration of tourists’ trips. Tourists who are attracted by these cultural activities tend to stay longer in a destination to explore the cultural offerings in detail.

In the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, where spa resorts are surrounded by a rich cultural heritage, participation in such activities can extend the length of tourists’ stay, providing them with a more complete and diversified experience.

H13. Participation in cultural activities at spa resorts influences the average duration of trips.

Participation in cultural activities can significantly influence the length of stay of tourists at spa resorts. Tourists who are attracted by cultural events, festivals or other similar activities tend to spend more time at the resort in order to fully enjoy these experiences.

Studies by McKercher and du Cros (2002) have shown that there is a correlation between participation in cultural activities and length of stay [

93]. These studies have demonstrated that cultural tourists are willing to spend longer periods at tourist destinations in order to have enough time to explore and participate in various cultural activities.

This hypothesis is based on research related to cultural tourism and tourist behavior [

93], adapted for the spa context. These studies used validated scales to measure the length of stay according to participation in cultural activities.