Methodological Reflection on Sustainable Tourism in Protected Natural Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Literature Review

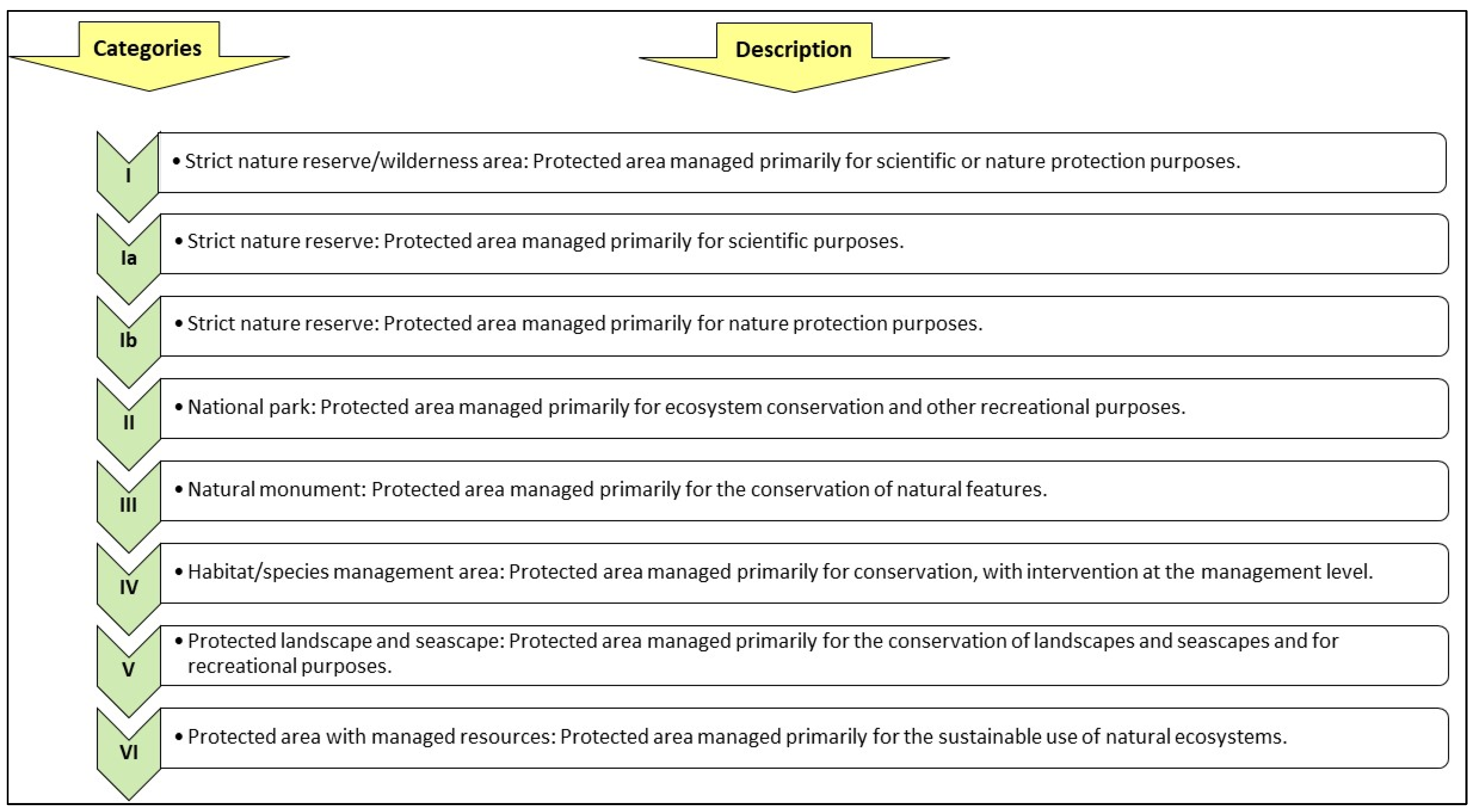

1.1.1. Definition and Background of Protected Natural Areas

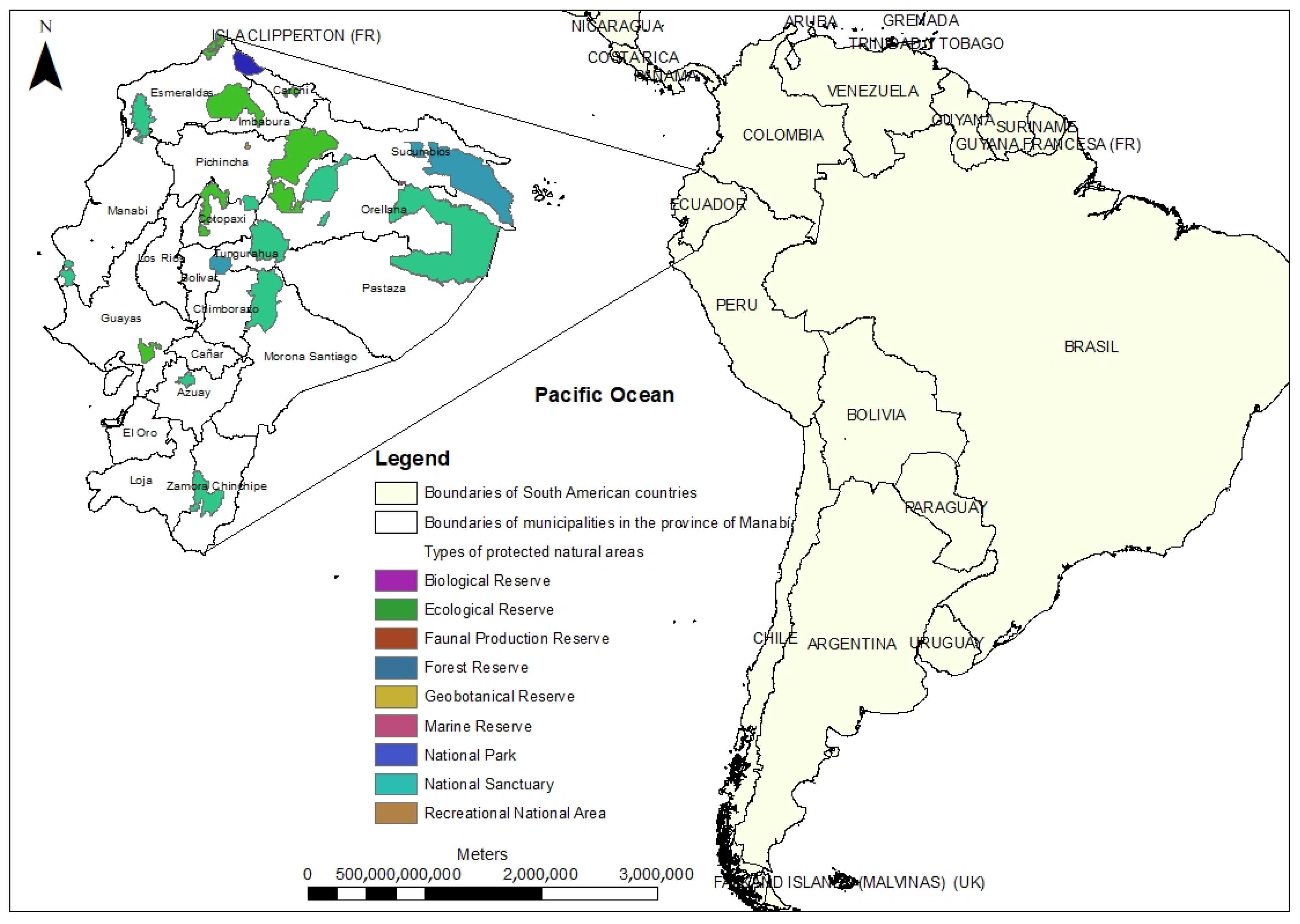

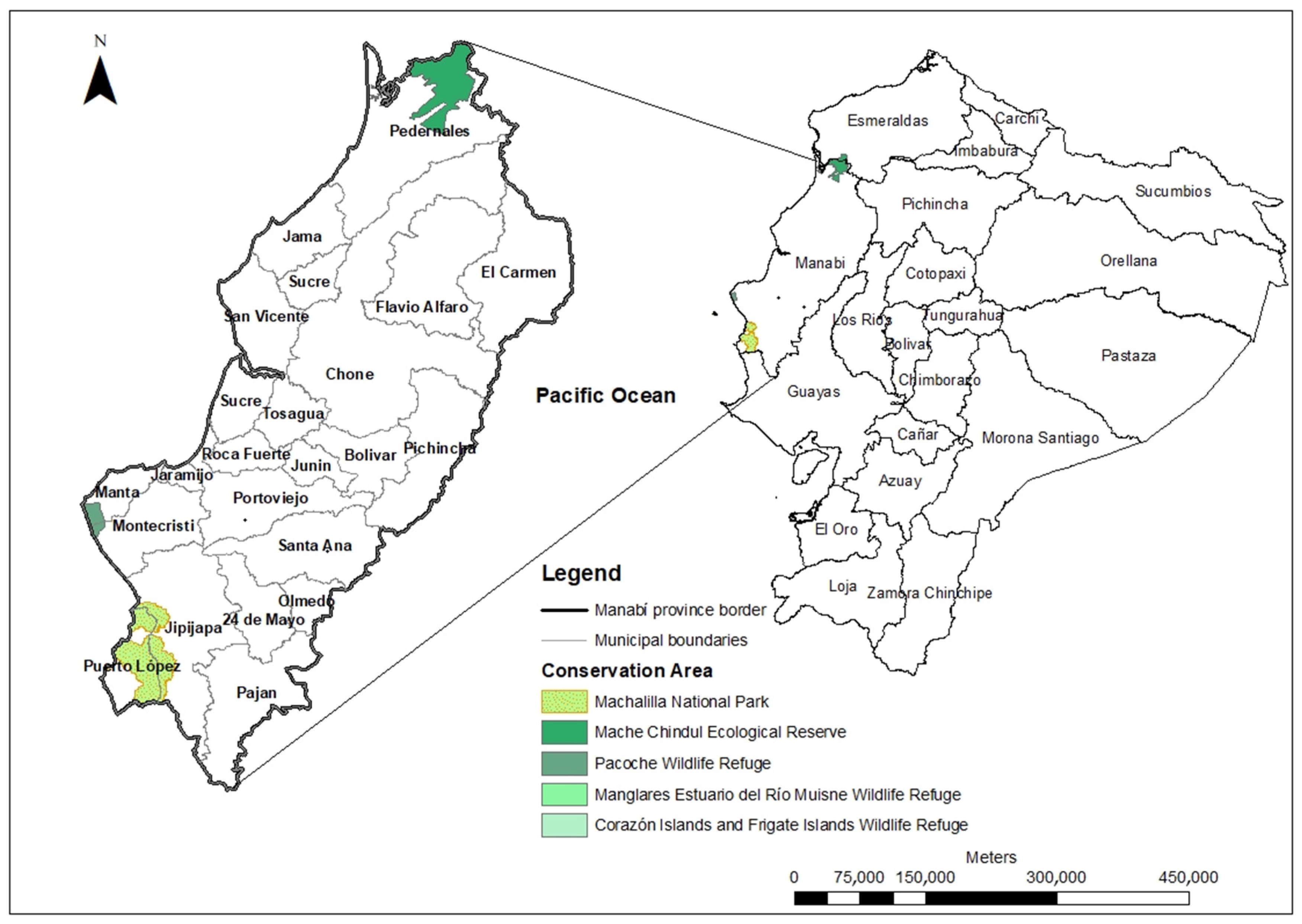

1.1.2. Protected Natural Areas in Ecuador

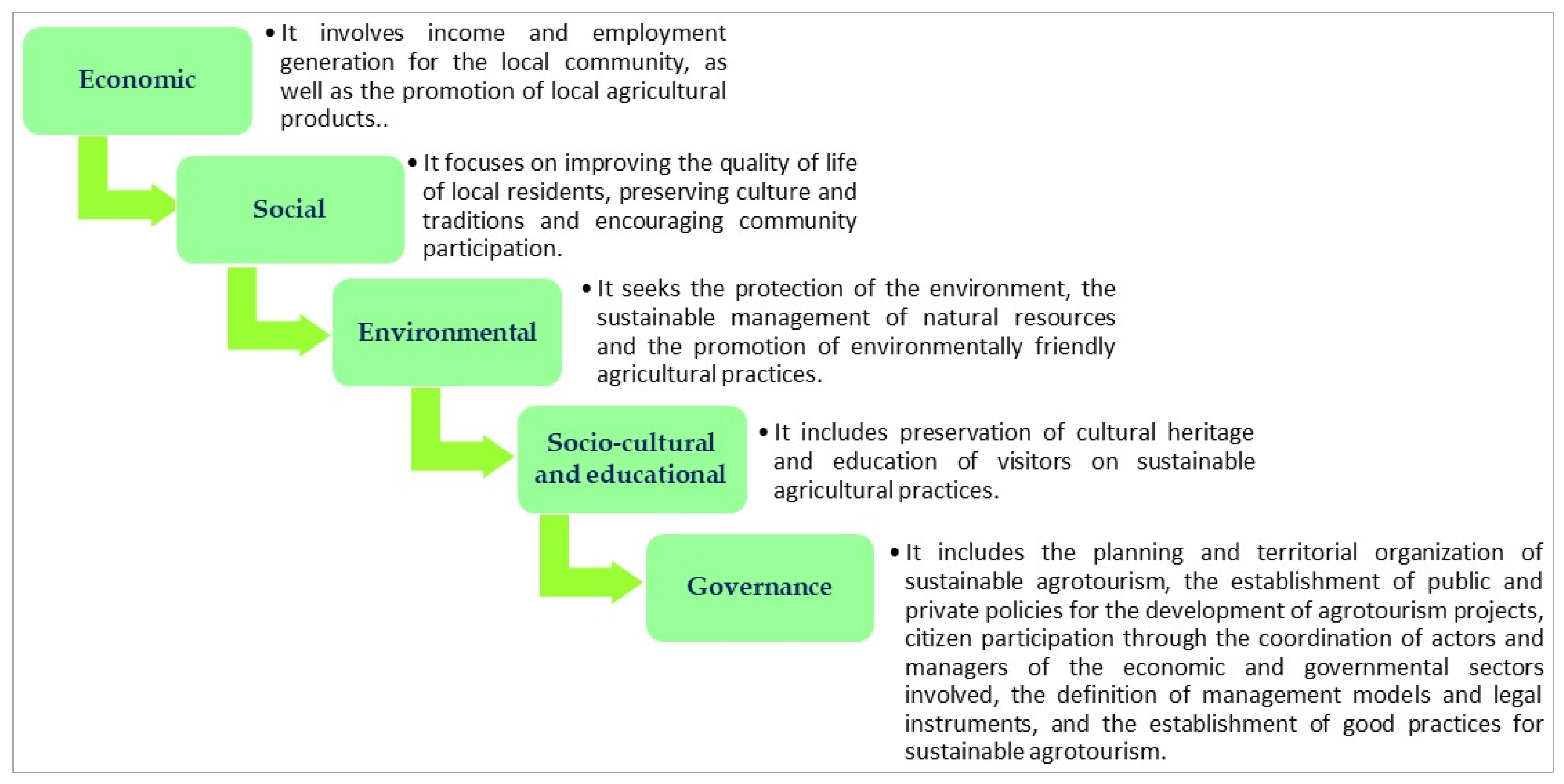

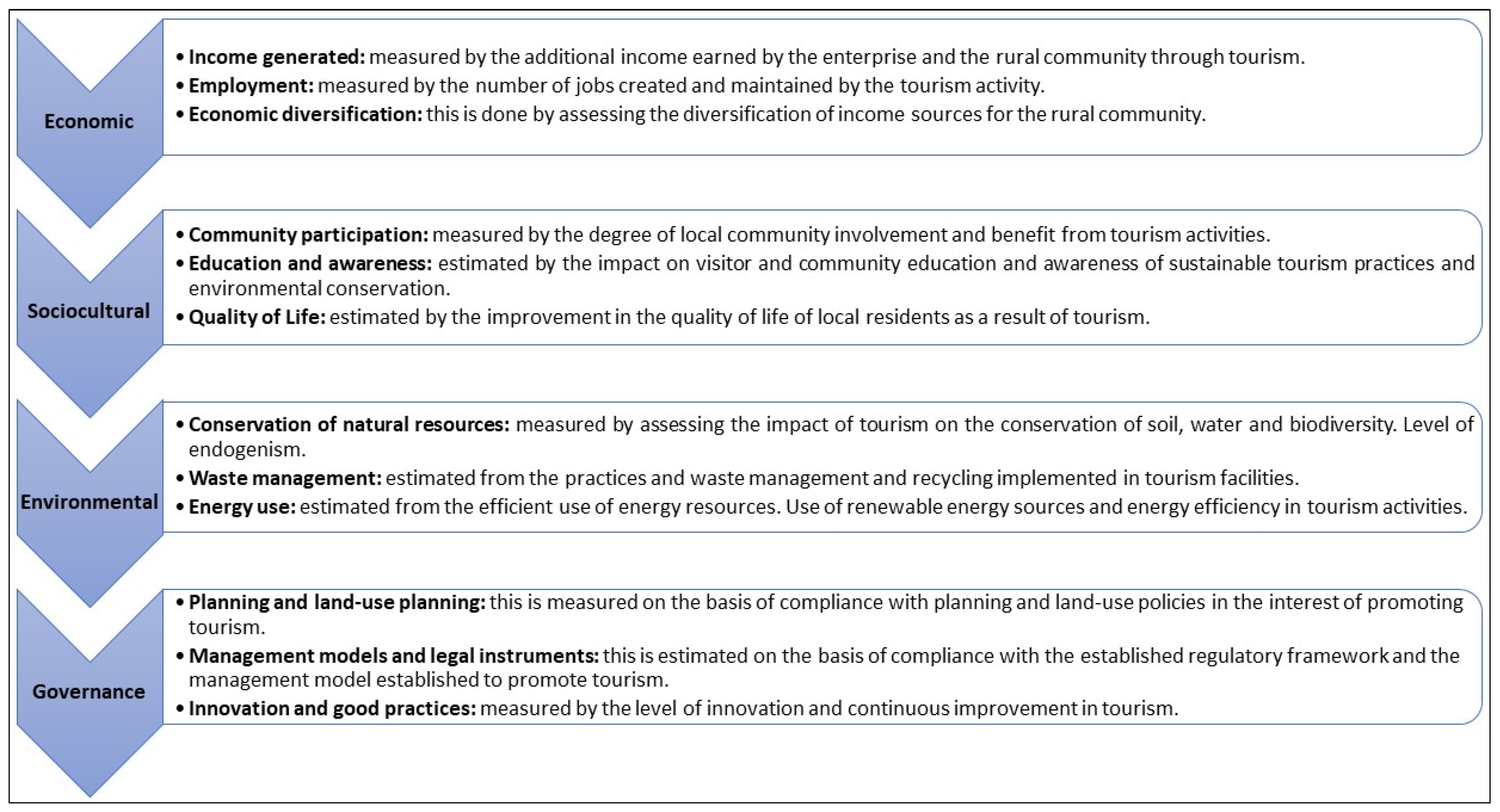

1.1.3. Dimensions and Indicators of Sustainability

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spatial and Temporal Delimitation

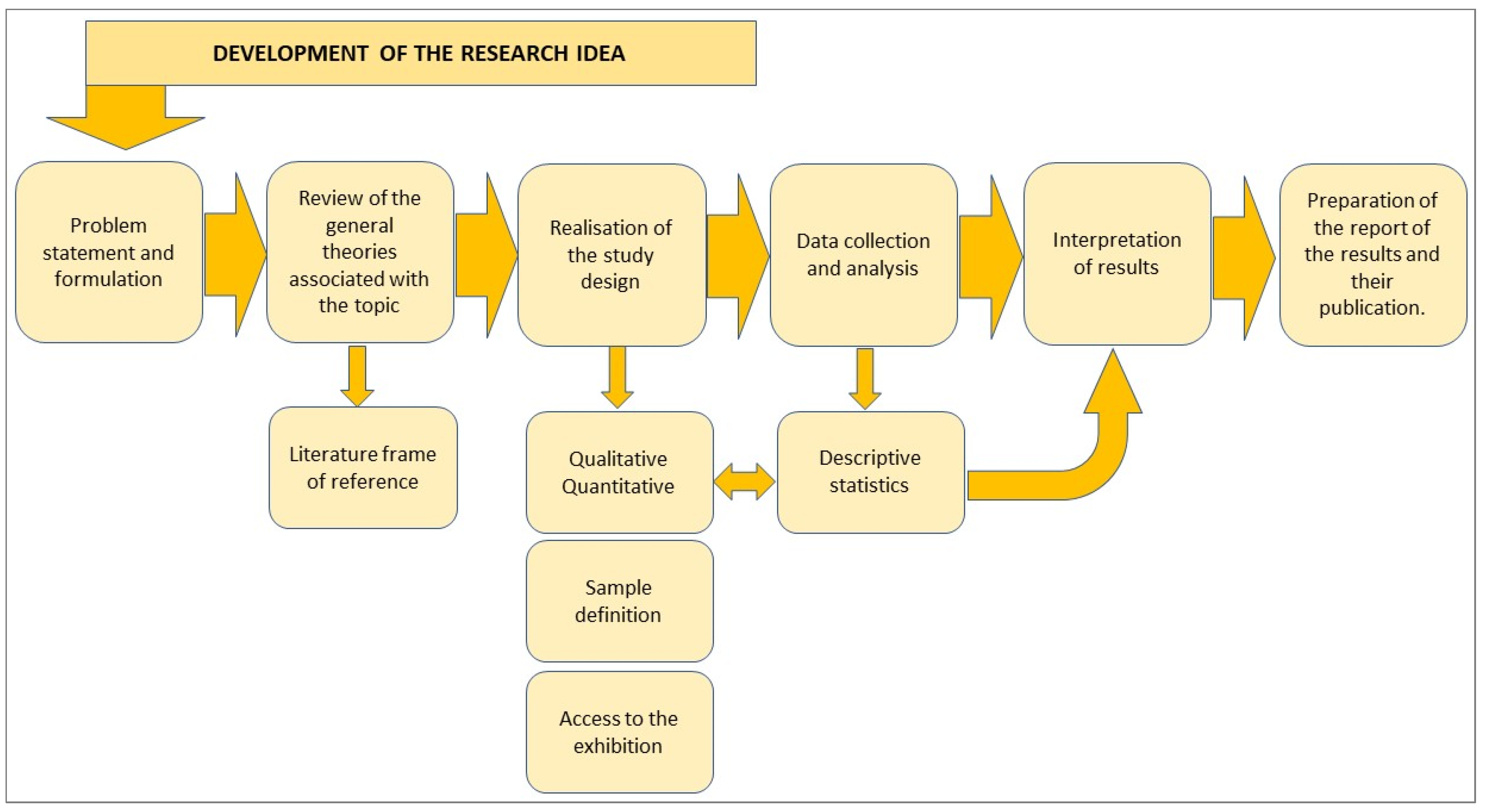

2.2. Methodology Applied

2.3. Expert Evaluation Method

3. Results

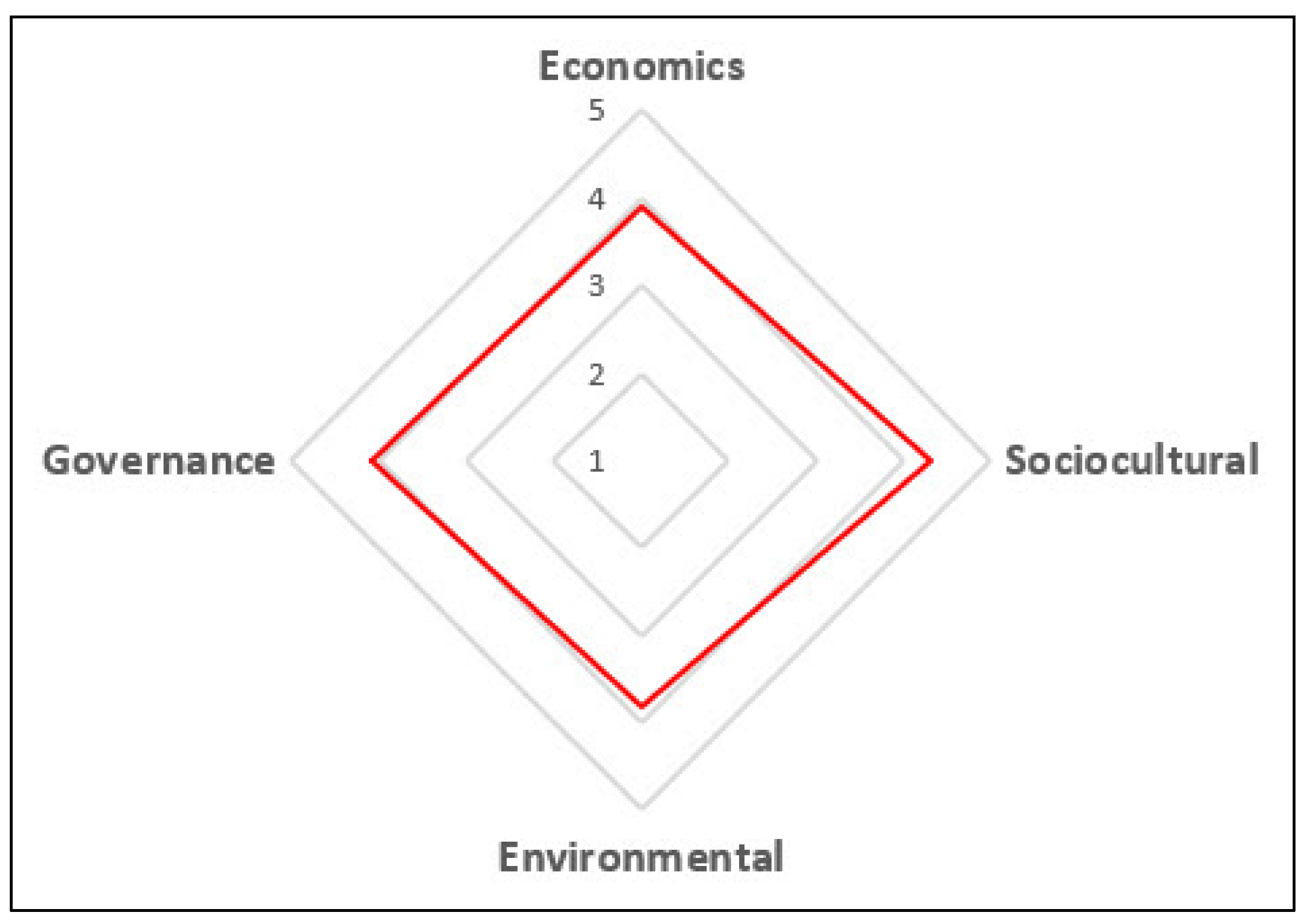

3.1. Survey of Tourism Managers

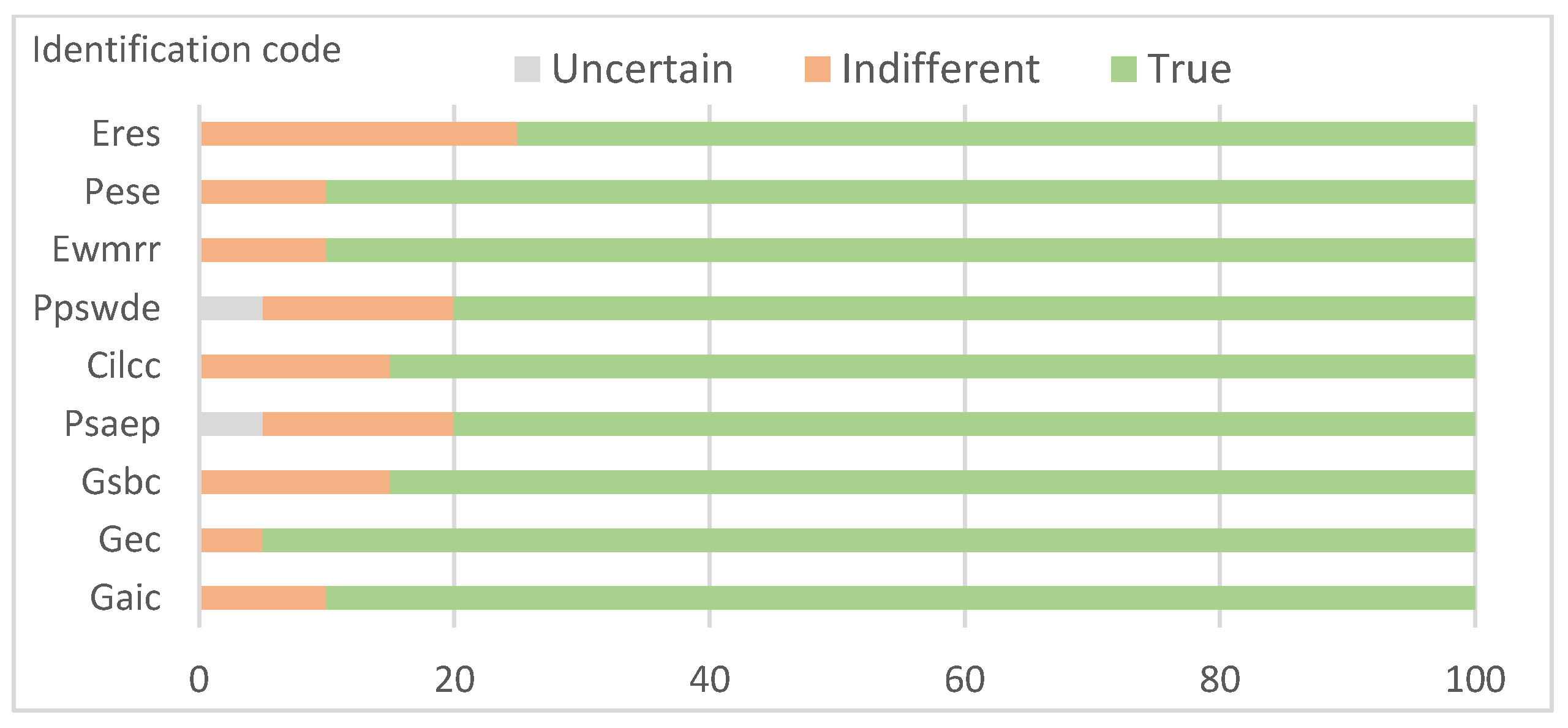

3.2. Tourist Survey

3.3. Expert Assessment

- Mean and median;

- Standard deviation;

- IQR (interquartile range)—useful for determining consensus.

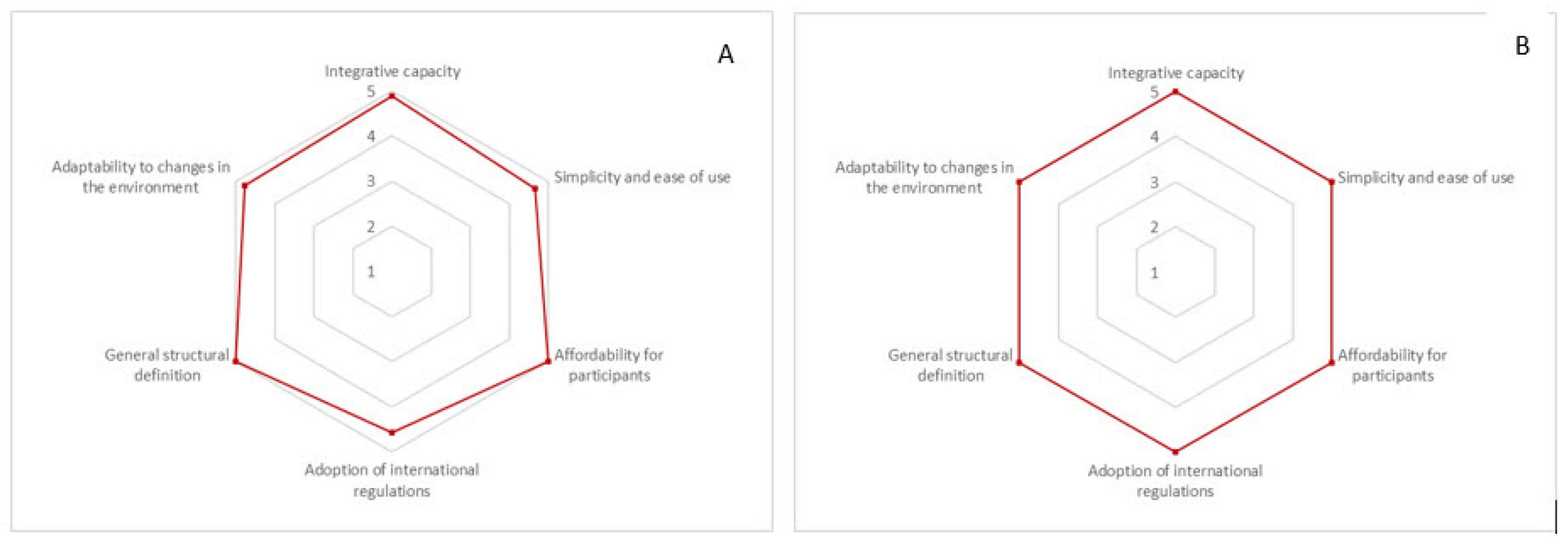

- Simplicity and ease of use;

- Adoption of international regulations.

- RIC = 1.0;

- Standard deviation ≥ 0.5.

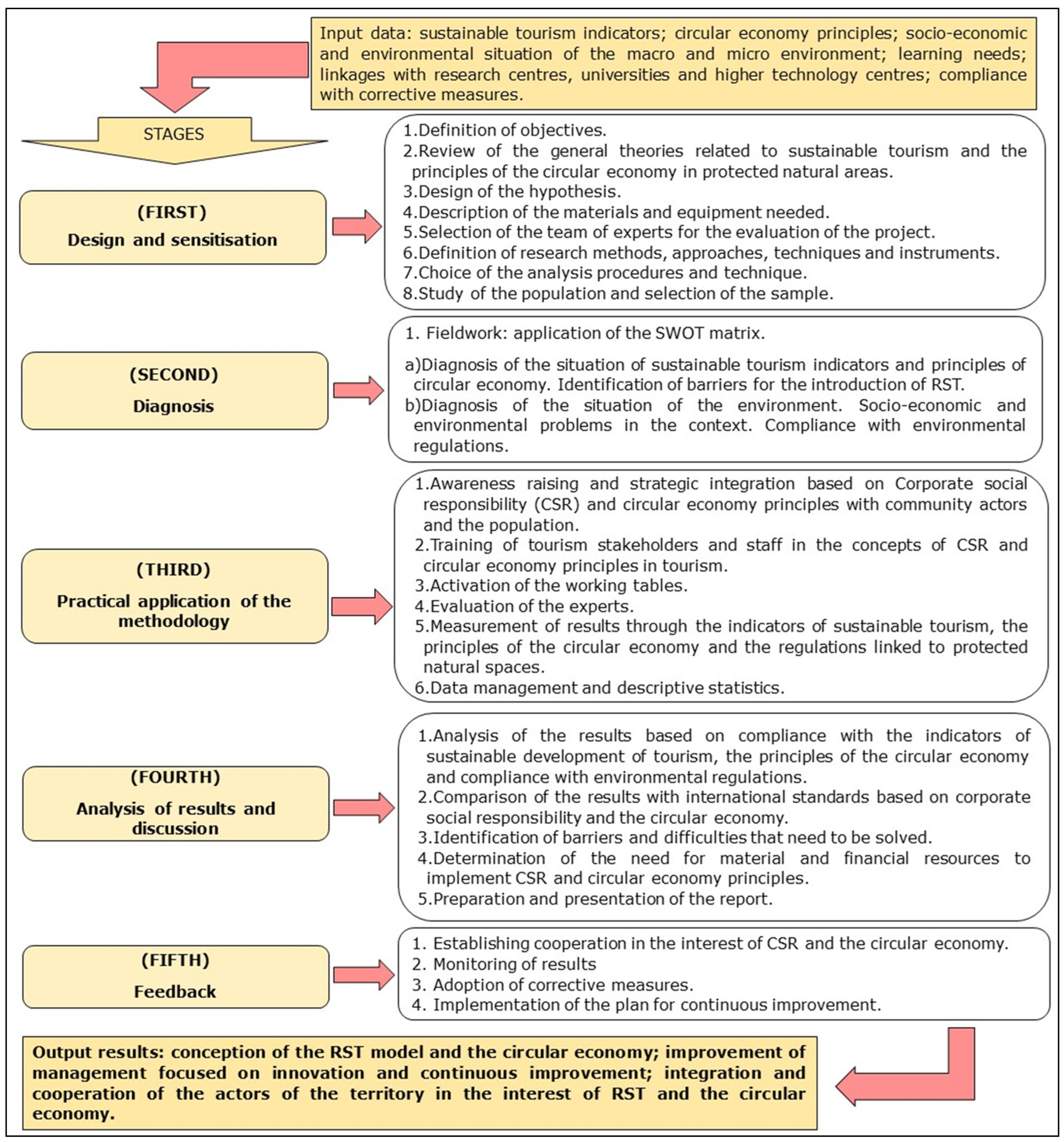

3.4. Methodology Design

4. Discussion

4.1. First Stage: Design Aspects and Awareness Raising

4.2. Second Stage: Diagnosis

4.3. Third Stage: Practical Application of the Methodology

4.4. Fourth Stage: Analysis of Results and Discussion

4.5. Fifth Stage: Feedback

4.6. Output Results

4.7. Practical and Theoretical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zeng, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y. Study on Livelihood Assets-Based Spatial Differentiation of the Income of Natural Tourism Communities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, P.J. Turismo activo y medio ambiente: Una implicación necesaria. Aspectos jurídicos. Cuad. Tur. 2010, 26, 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot-Spivack, S.M. Turismo y medio ambiente: Dos realidades sinérgicas. Pap. Tur. 2014, 29. Available online: https://www.turisme.gva.es/ojs/index.php/Papers/article/viewFile/204/171 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Whitford, M.; Ruhanen, L. Indigenous tourism research, past and present: Where to from here? In Sustainable Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 14–33. Available online: https://n9.cl/1mcfov (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Vacacela, A. Factores relevantes para la gestión de pequeñas empresas agroturísticas. Polo Conoc. 2023, 8, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta-Bejarano, N.; Vásquez-Farfán, B.; Ullauri-Donoso, N. Turismo sensorial y agroturismo: Un acercamiento al mundo rural y sus saberes ancestrales. Rev. Investig. Soc. 2018, 4, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capdevilla, D.; Vargas, F.; Restrepo, J.J. El turismo de naturaleza: Educación ambiental y beneficios tributarios para el desarrollo de Caquetá. Aglala 2020, 11, 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Makian, S.; Hanıfezadeh, F. Current challenges facing ecotourism development in Iran. J. Tour. 2021, 7, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, A.; Lastra, X. Los espacios naturales protegidos. Concepto, evolución y situación actual en España/Protected natural areas. Concept, evolution and current situation in Spain. M+ A Rev. Electrónica Medioambiente 2008, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; Stephen, F.M.; Christopher, D.H. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas Planning and Management Guidelines. United Nations Environment Programmed, World Tourism Organization and IUCN—World Conservation Union. 2002. Available online: https://www.institutobrasilrural.org.br/download/20120219144738.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Pelegrín-Entenza, N.; Vázquez-Pérez, A.; Pelegrín-Naranjo, A. Rural agrotourism development strategies in less favored areas: The case of Hacienda Guachinango de Trinidad. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauna, C. Percepción de la problemática asociada al turismo y el interés por participar de la población: Caso Puerto Vallarta. El Periplo Sustentable 2017, 33, 251–290. [Google Scholar]

- Castiñeira, C.J. La oferta turística complementaria en los destinos turísticos alicantinos: Implicaciones territoriales y opciones de diversificación. Investig. Geográficas (Esp) 1998, 19, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Rebollo, J.F.; Baños-Castiñeira, C.J. Turismo, Territorio y Medio Ambiente. La Necesaria Sostenibilidad. Universidad de Alicante. 2004. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/132322/1/Vera_Banos_2004_PapEconEsp.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Gordan, M.I.; Popescu, C.A.; Čalina, J.; Adamov, T.C.; Mănescu, C.M.; Iancu, T. Spatial Analysis of Seasonal and Trend Patterns in Romanian Agritourism Arrivals Using Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Using LOESS. Agriculture 2024, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, D. Competitividad Sostenible de los Espacios Naturales Protegidos Como Destinos Turísticos: Un Análisis Comparativo de los Parques Naturales Sierra de Aracena y Picos de Aroche y Sierras de Cazorla, Segura y Las Villas. Universidad de Huelva. 2007. Available online: https://n9.cl/o2lls (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Guerrero, V. Los espacios naturales protegidos como recurso turístico: Metodología para el estudio del Parque Nacional de Sierra Nevada. Estud. Turísticos 2001, 147, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madueño, J.; Larrán, M.; Lechuga, M.P.; Martínez-Martínez, D. Responsabilidad social en las pymes: Análisis exploratorio de factores explicativos. Rev. Contab. 2016, 19, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, B.G. Tras una definición de las áreas protegidas: Apuntes sobre la conservación de la naturaleza en Argentina. Rev. Univ. Geogr. 2018, 27, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Oli, K.P.; Chaudhary, S.; Raj, U. Are governance and management effective within protected areas of the Kanchenjunga landscape (Bhutan, India and Nepal). Parks 2013, 19, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdgate, M. The Green Web: A Union for World Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://n9.cl/mdvcf (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Ceruti, M. Yellowstone. Patrimonio y paisaje. Estud. Patrim. Cult. 2016, 15, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Contreras, M.E. Una mirada a los Parques Nacionales en el mundo. Caso: Parques nacionales en Venezuela y en el Estado Mérida. Visión Gerenc. 2011, 2, 405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, G. Directrices Para Áreas Marinas Protegidas; Comisión Mundial de Áreas Protegidas (CMAP): Gland, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N. Directrices para la Aplicación de las Categorías de Gestión de Áreas Protegidas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://n9.cl/xwrx2 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Cifuentes, M.; Izurieta, A.; Henrique, H. Medición de la Efectividad del Manejo de Áreas Protegidas. WWF IV. IUCN. V. GTZ. VI. Título. VII. 2000. 105p. Available online: https://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwfca_measuring_es.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Zambrano, R.; López, M. Breve Historia y Perspectivas para el Futuro del Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas del Ecuador (SNAP). VIII Jornadas Académicas Turismo y Patrimonio, Compartiendo lo Nuestro con el Mundo. Memorias Contribuciones Científicas. Memorias 42. 2015. Available online: https://n9.cl/s1v13 (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- ONU. Convenio Sobre la Diversidad Biológica. Organización de las Naciones Unidas. 1992. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-es.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Márquez, J.F. Reglamentos indígenas en áreas protegidas de Bolivia: El caso del Pilón Lajas. Rev. Derecho 2016, 46, 71–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwith, T.; Lawrence, H.; David, S. Protected Areas for Peace and Co-Operation. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines. Ed. Adrian Phillips, Series 7. 2001. Available online: http://web.bf.uni-lj.si/students/vnd/knjiznica/Skoberne_literatura/gradiva/zavarovana_obmocja/IUCN_TBPA.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Íñiguez, L.I.; Jiménez, C.L.; Sosa, J.; Ortega-Rubio, A. Categorías de las áreas naturales protegidas en México y una propuesta para la evaluación de su efectividad. Investig. Y Cienc. 2014, 22, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.J.B.; James, P. State of the World’s Protected Areas at the End of the Twentieth Century; UICN: Gland, Switzerland, 1997; Available online: https://aquadocs.org/handle/1834/867 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Hockings, M.; Sue, S.; Nigel, D. Evaluating Effectiveness: A Framework for Assessing the Management of Protected Areas; No. 6; UICN: Gland, Switzerland, 2000; Available online: https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:162233 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Hiernaux-Nicolas, D.; Cordero, A.; Duynen-Montijn, L. Imaginarios Sociales y Turismo Sostenible. Cuaderno de Ciencias Sociales 123; Sede Académica, Costa Rica, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales FLACSO: San José, Costa Rica, 2002; Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Costa_Rica/flacso-cr/20120815033220/cuaderno123.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Light, D.; Cretan, R.; Dunca, A.M. Museums and transitional justice: Assessing the impact of a memorial museum on young people in post-communist Romania. Societies 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L.; Albă, C. Museums as a means to (re)make regional identities: The Oltenia museum (Romania) as case study. Societies 2022, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Solís, D. Turismo Comunitario en Ecuador Desarrollo y Sostenibilidad Social, 1st ed.; Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2007; p. 333. Available online: https://rest-dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/server/api/core/bitstreams/e610c599-4d30-467b-a681-e1de3e2740cd/content (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Asamblea Nacional Legislativa. Código Orgánico del Ambiente. Registro Oficial Suplemento 983. Estado: Vigente. 2017. Available online: https://www.emaseo.gob.ec/documentos/lotaip_2018/a/base_legal/Codigo_organico%20de%20ambiente_2017.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Mendoza-Montesdeoca, I.; Rivera-Mateos, M.; Doumet-Chilán, Y. Políticas públicas ambientales y desarrollo turístico sostenible en las áreas protegidas de Ecuador. Rev. Estud. Andal. 2022, 43, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Blanco, K. Community-based ecotourism development ion the periphery of Belize. Curr. Issues Tour. 1999, 2, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.; Gulden, T.; Cousins, K.; Kraev, E. Integrating environmental, social and economic systems: A dynamic model of tourism in Dominica. Ecol. Model. 2004, 175, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, E.; Farthing, L.C. Communitarian tourism. Hosts and mediators in Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M. Espacios en Disputa: El Turismo en Ecuador, 1st ed.; Flacso: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; p. 232. Available online: http://190.57.147.202:90/xmlui/handle/123456789/1881 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Hiwasaki, L. Community-based tourism: A pathway to sustainability for Japan’s protected areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loor-Bravo, L.; Plaza-Macías, N.; Medina-Valdés, Z. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Apuntes en tiempos de pandemia. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 27, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, F.; Montero, R.; Rodríguez, S.; León, K. Agroturismo: Una alternativa sostenible para el desarrollo local en San Francisco de Milagro, Guayas, Ecuador. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Científica Multidiscip. 2023, 7, 4768–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.C.; Nazareno, R.; Sánchez, G.A. Agroturismo para el Desarrollo Sostenible en fincas ecuatorianas. Un estudio documental. Dominio Cienc. 2021, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla, J.V. Agroturismo, una alternativa sostenible para el sector rural en Floridablanca, Santander. Hum. Rev. 2022, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Haro, J.R. Agroturismo y Turismo Sostenible en la Comunidad de Tolóntag, Parroquia Píntag, Cantón Quito, Provincia de Pichincha. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo Ecuador, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2023. Available online: http://dspace.unach.edu.ec/handle/51000/11873 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Organización Mundial del Turismo. Indicadores de Desarrollo Sostenible Para Los Destinos Turísticos. Guía Práctica. Publicado e Impreso por la Organización Mundial del Turismo. 2005. Available online: https://www.ucipfg.com/Repositorio/MGTS/MGTS14/MGTSV-07/tema2/OMTIndicadores_de_desarrollo_de_turismo_sostenible_para_los_destinos_turisticos.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Sánchez, M.; Pulido, J.I. Medida de la Sostenibilidad Turística. Propuesta de un Índice Sintético. Investigación Turística; Universitaria Ramón Areces: Madrid, Spain, 2009; Available online: https://n9.cl/173949 (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Asociación Nacional de Operadores de Turismo Receptivo del Ecuador [OPTUR]. Indicadores Turismo Ecuador; OPTUR: Quito, Ecuador, 2024; Available online: https://optur.org/indicadores-turismo-ecuador/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- López, F.; Torres-Delgado, A.; Font, X.; Serrano, D. Gestión sostenible de destinos turísticos: La implementación de un sistema de indicadores de turismo en los destinos de la provincia de Barcelona. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2018, 77, 428–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Jiménez, J.L. Indicadores de sostenibilidad turística enfocados al turismo comunitario: Caso de estudio Comunidad Kichwa “Shayari”, Sucumbíos-Ecuador. Green World J. 2022, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiza, R.; Edison, M. Análisis histórico de la evolución del turismo en territorio ecuatoriano. RICIT Rev. Tur. Desarro. Y Buen Vivir 2012, 4, 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Represa, F.; Macías-Zambrano, L.H. Sostenibilidad social en Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Estudio de caso en el Parque Nacional Machalilla (Manabí, Ecuador). Rev. Científica Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2022, 23, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.; Ruiz, E. Resiliencia Socioecológica: Aportaciones y retos desde la Antropología. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 2011, 20, 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, V.; Valencia, C. Precisión y exactitud en los sistemas de información geográfica (SIG) en las investigaciones históricas. O Retorno Mapas. 2016, 1. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/32076439/Valencia_Villa_Carlos_and_Gil_Tiago_O_retorno_dos_Mapas_Sistemas_de_informa%C3%A7%C3%A3o_Geogr%C3%A1fica_em_Hist%C3%B3ria (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, L. Metodología de la Investigación. Sexta Edición. McGRAW-HILL/Interamericana Editores, S.A. DE C.V. 2014. Available online: https://n9.cl/l0j5h (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Naranjo, M.R. Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Community-Based Tourism: Contribution to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Hernández, J.E. El ecoturismo y el turismo rural en la región de las altas montañas de Veracruz, México: Potencial, retos y realidades. Agro Product. 2018, 11, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pompa, F.; Leyva-Fernández, L.C.; Ortiz-Pérez, O.L.; Sierra-Mulet, Y. El turismo rural sostenible en Holguín. Estudio prospectivo panorama 2030. El Periplo Sustentable 2020, 38, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ramírez, M.; Martínez-Cepena, M.C. Perfeccionamiento de un instrumento para la selección de expertos en las investigaciones educativas. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2012, 14, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-González, F.; Pérez-González, J.; Senior-Naveda, A.; García-Guliany, J. Validación del diseño de una red de cooperación científico-tecnológica utilizando el coeficiente K para la selección de expertos. Inf. Tecnológica 2021, 32, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Cabrera, D.A.; Vázquez-Erazo, E.J.; Ramón-Poma, G.M. Marketing experiencial aplicado al turismo rural del cantón Morona como componente de la Economía Naranja. Cienciamatria 2021, 7, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficapal, J.; Harold, G. Hacia un Turismo Responsable y Sostenible. Harvard Deusto Business Review 2013, Núm. 224, pp. 40–50. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14342/4356 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Bramwell, B.; Alletorp, L. Attitudes in the Danish tourism industry to the roles of business and government in sustainable tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K.E.; Gibson, C. Environmental sustainability in practice? A macroscale profile of tourist accommodation facilities in Australia’s coastal zone. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J.; Park, S.Y. An exploratory study of corporate social responsibility in the US travel industry. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X. Razones, Prácticas y Relaciones de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa en la Pequeña y Mediana Empresa Turística. Turismo y Sostenibilidad: V Jornadas de Investigación en Turismo. 2012, pp. 583–605. Available online: https://idus.us.es/items/5fe5e95e-b557-4d53-bb56-1040689eb384 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Sampaio, A.R.; Thomas, R.; Font, X. Why are some engaged and not others? Explaining environmental engagement among small firms in tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Cisneros, M.A.; Vela-Reyna, J.B.; Hernández-Perlines, F. La importancia de la responsabilidad social corporativa y la gestión de la calidad total en los hoteles de México. Dir. Y Organ. 2022, 76, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, L.; Balogh, A.; Huszár, P.; Tóth, A.; Bánhegyi, A. The possible development of the rural—Agrotourism in Hungary. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2020, 11, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A. Percepciones de la gestión del turismo en dos reservas de biosfera ecuatorianas: Galápagos y Sumaco. Investigaciones Geográficas. Boletín Inst. Geogr. 2017, 93, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Pareja, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Úbeda-García, M.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. The paradox between means and end: Workforce nationality diversity and a strategic CSR approach to avoid greenwashing in tourism accommodations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.L.; Díaz, N.P.M.; Vergara, D.A. El turismo en la matriz productiva de Ecuador: Resultados y retos actuales. Rev. Univ. Y Soc. 2018, 10, 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Nolivos, S.; Vergara, A.; Sorhegui, R.A. Responsabilidad social corporativa y el turismo sostenible. Rev. Científica ECOCIENCIA 2020, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón-Ávila, H. La medición del impacto económico del turismo: Metodología y principales resultados de la Cuenta Satélite del Turismo en la Unión Europea. Investig. Turísticas 2020, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.R.B.; Villarreal, L.Z.; Ramírez, C.A.P.; Rosano, C.M. La gestión comunitaria del turismo. Análisis desde el enfoque de los bienes comunes y los sistemas socio-ecológicos. Rev. Ra Ximhai 2018, 14, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, V. El turismo de naturaleza: Un producto turístico sostenible. Arbor 2017, 193, a396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.; Martínez, C.C. Turismo responsable: Propuesta para gestionar destinos turísticos regionales en la etapa post-COVID-19. Rev. Univ. Y Soc. 2022, 14, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.; Campón-Cerro, A.; Leco-Berrocal, F.; Pérez-Diaz, A. Diversificación agrícola y sostenibilidad de los sistemas agrícolas: Posibilidades para el desarrollo del agroturismo. Rev. Ing. Ambient. Y Gestión 2011, 10, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P.; Galioto, F.; Chiorri, M.; Vazzana, C. An integrated sustainability index based on agro-ecological and socio-economic indicators. A case study of organic agriculture without livestock in Italy. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, I. Revisión de Estudios Elemento Clave de la Gestión del Agroturismo. Seminario Complementario. Foro Nac. Manaj. Indones. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñán, R.J.; Leyva, M.Y.; Marcial, C.R.; Figueroa, S.E. Importancia de la preparación de los académicos en la implementación de la investigación científica. Conrado 2021, 17, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez, E.; Zepeda, M.I. Preparación de un proyecto de investigación. Cienc. Y Enfermería 2003, 9, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo, M.B.; Biviano, E.; Abirrached, M.T. Importancia de la Sensibilización Social Para Promover el Potencial Económico Local en San Miguel Canoa Puebla, México. Revista de Administración, Psicología e Ingeniería Industrial 2022, Año 8, No. 26, 152. Available online: https://n9.cl/cwt72 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Monsalve-Pelaez, M.; Tovar-Meléndez, A.; Salazar-Araujo, E. Revisión Documental sobre el Turismo Sostenible en el Marco de los ODS. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. (RTD)/J. Tour. Dev. 2023, 137. Available online: https://n9.cl/wbnil (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Frey, N.; George, R. Responsible tourism management: The missing link between business owners’ attitudes and behaviour in the Cape Town tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P.; Novotna, E. International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton’s we care! programme (Europe, 2006–2008). J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.D.P.; Cantallops, A.S. Responsabilidad social empresarial en el sector turístico. Estudio de caso en empresa de alojamiento de la ciudad de Santa Marta, Colombia. Estud. Y Perspect. Tur. 2012, 21, 1456–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Apospori, E.; Zografos, K.G.; Magrizos, S. SME corporate social responsibility and competitiveness: A literature review. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2012, 58, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, A.J.M.; Suarez, A.K.B.; Pacheco-Martínez, Z.K.; Gonzaga, J.A.R.; Calderón, J.E.Z.; Suárez, C.E.C. Diseños de investigación. Educ. Y Salud Boletín Científico Inst. Cienc. Salud Univ. Autónoma Estado Hidalgo 2019, 8, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha-Hospinal, L.F.; Chamorro-Mejía, R.; Oseda-Lazo, M.E.; Alania-Contreras, R.D. Evaluación de procedimientos empleados para determinar la población y muestra en trabajos de investigación de posgrado. Desafíos 2021, 12, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von, L.S. Mesas de Trabajo con Enfoque de Gobernanza: Su Implementación de Garantía de la Participación Ciudadana y Prevención de Conflictos Sociales. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad La Salle, Arequipa, Peru, 2024. Available online: http://repositorio.ulasalle.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12953/222 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Castillo, V.; Peláez, M.; López, L. Valoración del territorio para el fomento del turismo: Una aproximación desde los actores en cuestión. Conoc. Glob. 2021, 6, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, W.P.; Ramírez, J.F.; Pérez, I. Evaluación del turismo sostenible a partir de criterio de expertos en las costas de Manabí, Ecuador. Avances 2019, 21, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- García-González, J.R.; Sánchez-Sánchez, P.A. Diseño teórico de la investigación: Instrucciones metodológicas para el desarrollo de propuestas y proyectos de investigación científica. Inf. Tecnológica 2020, 31, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdigón, R.; Pérez, M.T. Herramientas de código abierto para el análisis estadístico en investigaciones científicas. An. Acad. Cienc. Cuba. 2022, 12. Available online: https://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S2304-01062022000300022&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Eslava-Schmalbalch, J.; Alzate, P. Cómo elaborar la discusión de un artículo científico. Rev. Colomb. Ortop. Y Traumatol. 2011, 25, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Manterola, C.; Pineda, V. ¿Cómo presentar los resultados de una investigación científica? Rev. Chil. Cirugía 2007, 59, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, R.; García-Ramos, A. Barreras y oportunidades para la inserción laboral de las personas con discapacidad en el sector turístico de la provincia de Alicante. Cuad. Tur. 2022, 49, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Herrera, F.A. El informe de investigación con estudio de casos. Magis. Rev. Int. Investig. Educ. 2009, 1, 413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, F.; Serna, H.M.; Naranjo, J.C. Redes empresariales locales, investigación y desarrollo e innovación en la empresa. Cluster de herramientas de Caldas, Colombia. Estud. Gerenciales 2013, 29, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, R. Cooperación en Investigación y Desarrollo en las Empresas Industriales Andaluzas. Economía Industrial. 2001, No 338. Available online: https://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10272/10814/Cooperacion_en_investigacion.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Feld, A.; Kreimer, P. Latinoamericanos en Proyectos Europeos: Asimetrías en la Cooperación Científica Internacional. Cienc. Tecnol. Y Política 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, I.I.; Valles, M.A. Dashboard digital para el monitoreo de indicadores y metas de los proyectos de consultores San Martín EIRL. Rev. Científica Sist. E Informática 2021, 1, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreras, I. La mejora continua: Elemento de competitividad empresarial. Rev. Electrónica Sobre Cuerpos Académicos Y Grupos Investig. 2022, 9. Available online: https://mail.cagi.org.mx/index.php/CAGI/article/view/253 (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Muñiz, D.E. Medidas correctivas y preventivas implementadas con la información generada por los programas de hemovigilancia. Rev. Mex. Med. Transfus. 2022, 14 (Suppl. S1), s60–s63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicators | Description | Frequencies | Participation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree (Indifferent) | Agree | Strongly Agree | |||

| (1 Point) | (2 Points) | (3 Points) | (4 Points) | (5 Points) | |||

| Economic | Tourism generates additional income for the community. | 30 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 18 | 6 |

| Sociocultural | The local community is involved and benefits from tourism, with a higher level of environmental awareness. | 0 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 15 | |

| Environmental | Tourism promotes soil, water, and biodiversity conservation. It encourages endogenism, the use of renewable sources, recycling, and the reuse of resources. | 1 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 9 | |

| Governance | Land use planning, management policies, and the regulatory framework promote tourism, innovation, and continuous improvement in the sector. | 2 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 12 | |

| Indicators | Identification Code | Participation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertain | Indifferent | True | ||

| Generates additional income for the community. | Gaic | 0 | 2 | 18 |

| Generates employment for the community. | Gec | 0 | 1 | 19 |

| It generates social benefits for the community. | Gsbc | 0 | 3 | 17 |

| Promotes sustainable agriculture and environmental protection. | Psaep | 1 | 3 | 16 |

| It contributes to improving the living conditions of the community. | Cilcc | 0 | 3 | 17 |

| Promotes the protection of soil, water, diversity and endogenism. | Ppswde | 1 | 3 | 16 |

| Encourages waste management and resource recycling. | Ewmrr | 0 | 2 | 18 |

| Promotes the efficient use and saving of energy. | Pese | 0 | 2 | 18 |

| Encourages the use of renewable energy sources. | Eres | 0 | 5 | 15 |

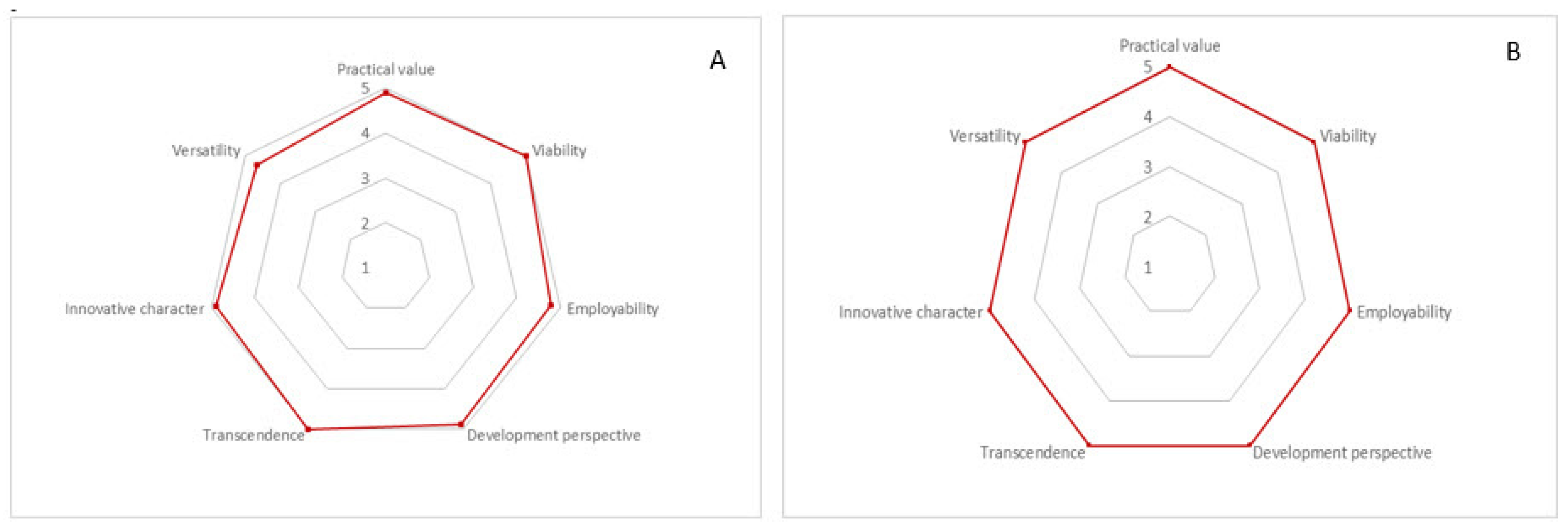

| Indicators | Rating According to Expert Judgement | W de Kendall 0.181 Chi-square 6.5 Asymptotic sig 0.37 | ||||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | ||

| Practical value | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Viability | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Employability | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Development perspective | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Transcendence | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Innovative character | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Versatility | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Kendall’s W value 0.063 | Chi-square 2.222 | Asymptotic sig 0.818 | ||||||||

| No. | Average | Medium | Standard Deviation | ICR (Interquartile Range) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Practical value | 4.888888888888889 | 5.0 | 0.33333333333333337 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Viability | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | Employability | 4.777777777777778 | 5.0 | 0.4409585518440984 | 0.0 |

| 4 | Development perspective | 4.888888888888889 | 5.0 | 0.33333333333333337 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Transcendence | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6 | Innovative character | 4.888888888888889 | 5.0 | 0.33333333333333337 | 0.0 |

| 7 | Versatility | 4.777777777777778 | 5.0 | 0.4409585518440984 | 0.0 |

| Indicators | Rating According to Expert Judgement | W de Kendall 0.1 Chi-square 3.6 Asymptotic sig 0.731 | ||||||||

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | ||

| Integrative capacity | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Simplicity and ease of use | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Affordability for participants | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Adoption of international regulations | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| General structural definition | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Adaptability to changes in the environment | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Kendall’s W value 0.209 | Chi-square 7.308 | Asymptotic sig 0.199 | ||||||||

| No. | Average | Medium | Standard Deviation | ICR (Interquartile Range) | ¿Reassess? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Integrative capacity | 4.888888888888889 | 5.0 | 0.33333333333333337 | 0.0 | False |

| 2 | Simplicity and ease of use | 4.666666666666667 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | True |

| 3 | Affordability for participants | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | False |

| 4 | Adoption of international regulations | 4.555555555555555 | 5.0 | 0.5270462766947298 | 1.0 | True |

| 5 | General structural definition | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | False |

| 6 | Adaptability to changes in the environment | 4.777777777777778 | 5.0 | 0.4409585518440984 | 0.0 | False |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Vera, B.M.; Pelegrín-Entenza, N. Methodological Reflection on Sustainable Tourism in Protected Natural Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146558

López-Vera BM, Pelegrín-Entenza N. Methodological Reflection on Sustainable Tourism in Protected Natural Areas. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146558

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Vera, Boris Miguel, and Norberto Pelegrín-Entenza. 2025. "Methodological Reflection on Sustainable Tourism in Protected Natural Areas" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146558

APA StyleLópez-Vera, B. M., & Pelegrín-Entenza, N. (2025). Methodological Reflection on Sustainable Tourism in Protected Natural Areas. Sustainability, 17(14), 6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146558