Toward an Experimental Common Framework for Measuring Double Materiality in Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Concepts and Foundations of Double Materiality

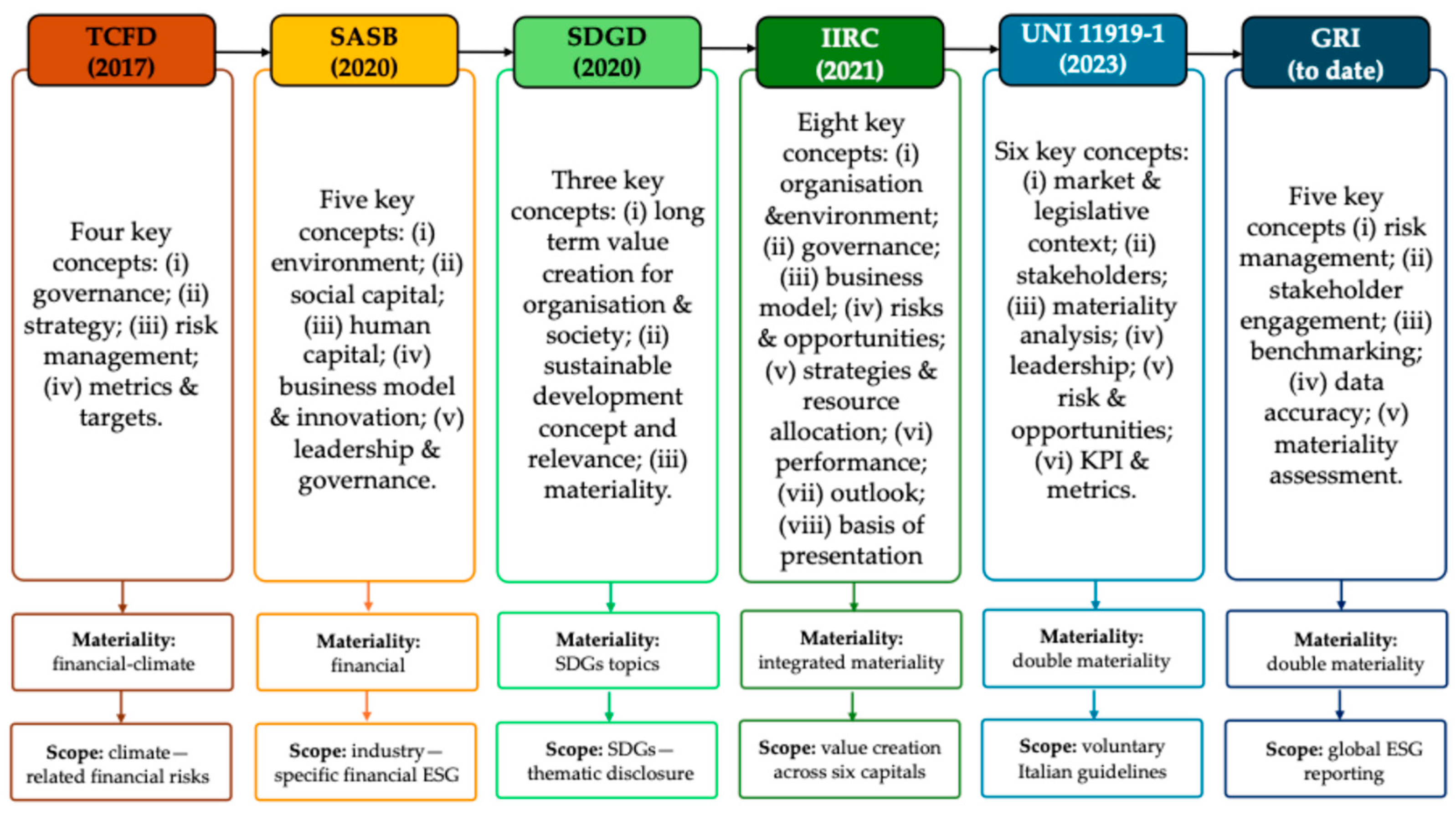

2.2. Historical Progression of Non-Financial Reporting and Double Materiality Assessment

2.3. Double Materiality Between Sectors and Company Dimensions

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

- AQ1.

- Which is the definition of materiality adopted in the standard?

- AQ2.

- What is defined as “sustainability materiality” in the standard?

- AQ3.

- What is defined as “financial materiality” in the standard?

- AQ4.

- Does the standard refer to different types of capital?

- AQ5.

- Who are the stakeholders identified in the standard?

- AQ6.

- How are the double materiality topics organized in the standard?

- AQ7.

- How is the materiality assessment performed in the standard?

- AQ8.

- Does the standard identify thresholds?

- AQ9.

- Does the standard suggest leveraging other sources?

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Definition of Materiality (AQ1, AQ2, and AQ3)

4.2. Types of Capital Considered in the Standard (AQ4)

4.3. Stakeholders to Whom the Standard Is Addressed (AQ5)

4.4. Topics of Double Materiality Considered in the Standard (AQ6)

4.5. Steps for Assessing Double Materiality (AQ7)

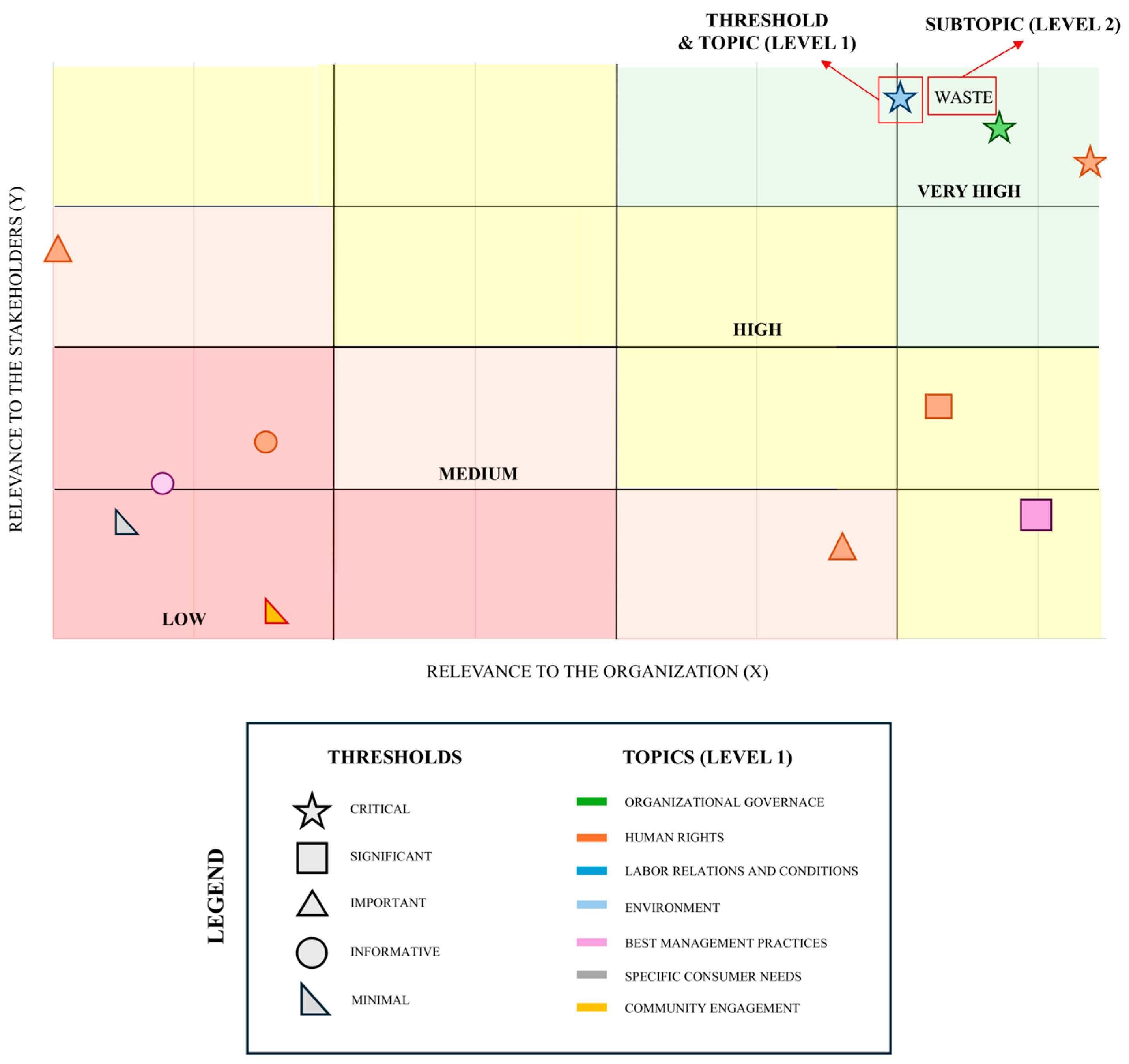

4.6. Thresholds (AQ8)

4.7. Integration with Other Sources (AQ9)

5. Discussion

5.1. Discretion or Determinism in Defining Double Materiality Measurement Guidelines?

5.2. How to Translate Material and Financial Impacts into Concrete Corporate Strategies?

5.3. Graphic Communication of the Double Materiality

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cicchini, D.; Cotana, M.L.; Filocamo, M.R.; Galeotti, R.M. Sustainability reporting practices in SMEs. A systematic study and future avenues. Piccola Impresa Small Bus. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaningsih, S.; Widjojo, R.; Kelle, P. Challenges and opportunities in sustainability reporting: A focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2298215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qalati, S.A.; Fan, M. Effects of sustainable innovation on stakeholder engagement and societal impacts: The mediating role of stakeholder engagement and the moderating role of anticipatory governance. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2406–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Oduro, S.; Gennaro, A. Stakeholder engagement for sustainable value co-creation: Evidence from made in Italy SMEs. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2025, 34, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Kaur, A.; Argento, D.; Sharma, U.; Soobaroyen, T. Everything, everywhere, all at once: The role of accounting and reporting in achieving sustainable development goals. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2025, 37, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, S.; Sigurjonsson, T.O. A Need for Standardized Approaches to Manage Sustainability Strategically. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. (2014/195/EU): Council Decision of 17 February 2014 authorising Member States to sign, ratify or accede to the Cape Town Agreement of 2012 on the Implementation of the Provisions of the Torremolinos Protocol of 1993 relating to the Torremolinos International Convention for the Safety of Fishing Vessels, 1977 Text with EEA relevance. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2014, 106, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2022, 322, 15–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoni, A.; Kiseleva, E. Do SMEs have an ESG communication strategy? Exploring the quality and influencing factors of voluntary ESG disclosures using web-based and annual report channels. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1267–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momtaz, P.P.; Parra, I.M. Is sustainable entrepreneurship profitable? ESG disclosure and the financial performance of SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2025, 64, 1535–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, Z. To whom are directors accountable? Stakeholder governance and the controversy over the amendment to Article 382-3 of the Korean Commercial Act. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2524582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, H.; Amarayil Sreeraman, B. From financial reporting to ESG reporting: A bibliometric analysis of the evolution in corporate sustainability disclosures. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 13769–13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Méndez, M.J.; Pajuelo-Moreno, M.-L.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D. A meta-analytic review of the sustainability disclosure and reputation relationship: Aggregating findings in the field of social and environmental accounting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 15, 1210–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboukardos, D.; Gaia, S.; Lassou, P.; Soobaroyen, T. The multiverse of non-financial reporting regulation. Account. Forum 2023, 47, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Commission Adopts the European Sustainability Reporting Standards. 2023. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-adopts-european-sustainability-reporting-standards-2023-07-31_en (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- European Commission. Corporate Sustainability Reporting. 2025. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/capital-markets-union-and-financial-markets/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Fiandrino, S.; Tonelli, A.; Devalle, A. Sustainability materiality research: A systematic literature review of methods, theories and academic themes. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2022, 19, 665–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calace, D. Materiality: From accounting to sustainability and the SDGs. In Responsible Consumption and Production; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, S.; Mjøs, A.; Pedersen, L.J.T. Sustainability reporting and approaches to materiality: Tensions and potential resolutions. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2022, 13, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFRAG. EFRAG Workstreams. 2025. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/en/sustainability-reporting/esrs-workstreams (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- GRI. GRI 3: Material Topics 2021. 2024. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/gri-standards-english-language/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- UNI 11919-1:2023; Modello Applicativo Nazionale Della UNI EN ISO 26000:2020—Parte 1: Indirizzi Applicativi Alla UNI EN ISO 26000 Guida Alla Responsabilità Sociale. UNI: Milano, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-11919-1-2023 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Garst, J.; Maas, K.; Suijs, J. Materiality assessment is an art, not a science: Selecting ESG topics for sustainability reports. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2022, 65, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.A. The concept of materiality. Account. Rev. 1967, 42, 86–95. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/243978 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Materiality and external assurance in corporate sustainability reporting: An exploratory study of Europe’s leading commercial property companies. J. Eur. Real. Estate Res. 2016, 9, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishkoff, P. An empirical investigation of the concept of materiality in accounting. J. Account. Res. 1970, 8, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshan, A.M.I.; Low, M.; de Villiers, C. Challenges of, and techniques for, materiality determination of non-financial information used by integrated report preparers. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 626–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ceballos, J.; Ortiz-De-Mandojana, N.; Antolín-López, R.; Montiel, I. Connecting the Sustainable Development Goals to firm-level sustainability and ESG factors: The need for double materiality. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2023, 26, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.; Mayer, C. Seeing double corporate reporting through the materiality lenses of both investors and nature. Account. Forum 2025, 49, 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristofaro, T.; Gulluscio, C. In search of double materiality in non-financial reports: First empirical evidence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, K.; Islam, M.K.S.; Evers, W. A case study on the blended reporting phenomenon: A comparative analysis of voluntary reporting frameworks and standards—GRI, IR, SASB, and CDP. Int. J. Sustain. Policy Pract. 2023, 19, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, Y.; Haslam, C.; Malberti, C. ELI Guidance on Company Capital and Financial Accounting for Corporate Sustainability; European Law Institute: Vienna, Austria, 2023; ISBN 9783950531817. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4339435 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Mio, C.; Fasan, M.; Costantini, A. Materiality in integrated and sustainability reporting: A paradigm shift? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on the Review Clauses in Directives 2013/34/EU, 2014/95/EU, and 2013/50/EU (SWD (2021) 81 Final). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0199 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Hummel, K.; Jobst, D. An overview of corporate sustainability reporting legislation in the European Union. Account. Eur. 2024, 21, 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raith, D. The contest for materiality. What counts as CSR? J. Appl. Account. Res. 2023, 24, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odobaša, R.; Marošević, K. Expected contributions of the European corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD) to the sustainable development of the European Union. EU Comp. Law. Issues Chall. Ser. 2023, 7, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primec, A.; Belak, J. Sustainable CSR: Legal and managerial demands of the new EU legislation (CSRD) for the future corporate governance practices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Yaqub, M.; Lee, S.H. Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: A scientometric review of global trends. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 2965–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.; Michelon, G. Conceptions of materiality in sustainability reporting frameworks: Commonalities, differences and possibilities. In Handbook of Accounting and Sustainability; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Henri, J.F. Is sustainability performance comparable? A study of GRI reports of mining organizations. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 283–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Druckman, P.B.; Picot, R.C. Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure (SDGD) Recommendations; ACCA: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://integratedreporting.ifrs.org/resource/sustainable-development-goals-disclosure-sdgd-recommendations/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). The International Framework; IIRC: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://integratedreporting.ifrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/IntegratedReporting_Framework_061024.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Adams, C.A.; Alhamood, A.M.; He, X. The development and implementation of GRI standards: Practice and policy issues. In Handbook of Accounting and Sustainability; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI. G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines; Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. GRI Universal Standards: GRI 101, GRI 102, and GRI 103—Exposure Draft; Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 26000:2020; Social responsibility. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- CDP. Supply Chain Report 2022. Available online: https://www.cdp.net/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Sullivan, R.; Gouldson, A. Environmental Policy and Business Strategy: Towards a Framework for Materiality Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 636–647. [Google Scholar]

- EFRAG. European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). Available online: https://www.efrag.org (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- European Commission. Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting: Supplement on Reporting Climate-Related Information. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Adams, C.A.; Alhamood, A.; He, X.; Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. The Double-Materiality Concept Application and Issues; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. GRI 101: Foundation; Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SASB. SASB Standards overview. Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/standards/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- SASB. SASB Conceptual Framework; Sustainability Accounting Standards Board: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/SASB-Conceptual-Framework.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- SASB. Proposed Changes to the SASB Conceptual Framework and Rules of Procedure: Bases for Conclusions and Invitation to Comment on Exposure Drafts; Sustainability Accounting Standards Board: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/PCP-package_vF.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TFCD). Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures; TCFD: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Benameur, K.B.; Mostafa, M.M.; Hassanein, A.; Shariff, M.Z.; Al-Shattarat, W. Sustainability reporting scholarly research: A bibliometric review and a future research agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74, 823–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Aluculesei, A.C.; Lagioia, G.; Pamfilie, R.; Bux, C. How to manage and minimize food waste in the hotel industry? An exploratory research. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 15th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Quantitative and qualitative research: Further reflections on their integration. In Mixing Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Research; Brannen, J., Ed.; Avebury: Brookfield, VT, USA, 1992; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- UNI/PdR 18:2016; Responsabilità Sociale Delle Organizzazioni—Indirizzi Applicativi Alla UNI ISO 26000. UNI: Milano, Italy, 2016. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-pdr-18-2016 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Ward Heimdal, J. The Impact of Discretionary Sustainability Disclosure on Sustainability Performance. An Analysis of Firms in the Petroleum Industry and Their Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Master’s Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023; pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 59020:2024; Circular Economy—Measuring and Assessing Circularity Performance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 14055; Environmental Management—Guidelines for Establishing Good Practices for Combatting Land Degradation and Desertification. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Bahnaru, R.; Hlaciuc, E. Circular economy measurement tools, challenges, and global standardization. Eur. J. Account. Financ. Bus. 2024, 12, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Misino, E.; Primiceri, M.; Bux, C. An application of the UNI/TS 11820:2022 on the measurement of circularity in an electronic equipment manufacturing organization in Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Levin, T.; Colding, J.; Sjöberg, S.; Barthel, S. Navigating complexity with the four pillars of social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 5929–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da.Mi. Bilancio di Sostenibilità 2023. 2024. Available online: https://dami.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Dami-Bilancio-di-Sostenibilita-2023_compressed.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Sofidel. Clean Living. Report Integrato 2023. 2024. Available online: https://report-integrato.sofidel.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Sofidel_Report_integrato_2023_IT.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

| Capital | EFRAG | UNI 11919 | GRI | IIRC | SASB | SDGD | TCFD | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | X | X | X | X | Pool of funds that is available to an organization for use in the production of goods or the provision of services obtained through financing or generated through operations or investments (i.e., debt, equity, grants). | |||

| Manufactured | X | X | X | Manufactured physical objects that are available to an organization for use in the production of goods or the provision of services (e.g., buildings, equipment, tools infrastructure). | ||||

| Natural | X | X | X | X | Renewable and non-renewable environmental stocks that provide goods and services that support the current and future prosperity of an organization (e.g., air, land, water, minerals, energy). | |||

| Intellectual | X | X | X | X | Organizational, knowledge-based intangibles (e.g., intellectual property, patents, copyrights, software). | |||

| Human | X | X | X | X | People’s competencies, capabilities and experience, and their motivations to innovate, but also employee turnover, labor/management relations, occupational health and safety, training and education, diversity and equal opportunities. | |||

| Social | X | X | X | X | Institutions and relationships established within and between each community, group of stakeholders and other networks (e.g., shared norms, key relationships, community). |

| Standard | Item | Scale Impact | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| EFRAG | Scale of impact | From 0 to 5 | 0 = None 1 = Minimal 2 = Low 3 = Medium 4 = High 5 = Absolute |

| Scope of impact | From 0 to 5 | 0 = None 1 = Limited 2 = Concentrated 3 = Medium 4 = Widespread 5 = Global/total | |

| Remediability of impact | From 0 to 5 | 0 = Very easy to remedy 1 = Relatively easy to remedy (short-term) 2 = Remediable with effort (time and cost) 3 = Difficult to remedy or mid-term 4 = Very difficult to remedy or long-term 5 = Non-remediable/irreversible |

| Standard | Item | Scale Impact | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNI 11919 | Probability (of the risk) | From 1 to 4 | 1 = Unlikely 2 = Low likely 3 = Likely 4 = Very likely |

| Consequence (of the risk) | From 1 to 4 | 1 = Negligible 2 = Mild 3 = Medium 4 = High | |

| K factor (human risk management) | From 1 to 4 | 1 = Low 2 = Medium 3 = High 4 = Optimal |

| TOPIC (ISO 26000) | SECTORS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil and gas (GRI 11) | Coal (GRI 12) | Agr. Aqua. Fis. (GRI 13) | Mining (GRI 14) | |

| ORGANIZATIONAL GOVERNANCE | Anti-competitive behavior | Anti-competitive behavior | ||

| Anti-corruption | Anti-corruption | Anti-corruption | Anti-corruption | |

| Payments to governments | Payments to governments | Payments to governments | ||

| Public policy | Public policy | Public policy | Public policy | |

| HUMAN RIGHTS | Occupational health and safety | Occupational health and safety | Occupational health and safety | Occupational health and safety |

| Non-discrimination and equal opportunity | Non-discrimination and equal opportunity | Non-discrimination and equal opportunity | Non-discrimination and equal opportunity | |

| Forced labor and modern slavery | Forced labor and modern slavery | Forced or compulsory labor | Forced labor and modern slavery | |

| Child labor | Child labor | Child labor | ||

| LABOR RELATIONS AND CONDITIONS | Employment practices | Employment practices | Employment practices | Employment practices |

| Freedom of association and collective bargaining | Freedom of association and collective bargaining | Freedom of association and collective bargaining | Freedom of association and collective bargaining | |

| Living income and living wage | ||||

| ENVIRONMENT | GHG emissions | GHG emissions | Emissions | GHG emissions |

| Climate adaptation, resilience, and transition | Climate adaptation, resilience, and transition | Climate adaptation and resilience | Climate adaptation and resilience | |

| Air emissions | Air emissions | Air emissions | ||

| Biodiversity | Biodiversity | Biodiversity | Biodiversity | |

| Waste | Waste | Waste | Waste | |

| Water and effluents | Water and effluents | Water and effluents | Water and effluents | |

| Closure and rehabilitation | Closure and rehabilitation | Natural ecosystem conversion | Closure and rehabilitation | |

| Pesticides use | Tailings | |||

| Soil health | ||||

| BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES | Asset integrity and critical incident management | Asset integrity and critical incident management | Animal health and welfare | Security practices |

| Critical incident management | ||||

| SPECIFIC CONSUMER NEEDS | Food safety | |||

| Food security | ||||

| Supply chain traceability | ||||

| COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT | Economic impacts | Economic impacts | Economic inclusion | Economic impacts |

| Local communities | Local communities | Local communities | Local communities | |

| Land and resource rights | Land and resource rights | Land and resource rights | Land and resource rights | |

| Rights of indigenous people | Rights of indigenous people | Rights of indigenous people | Rights of indigenous people | |

| Conflict and security | Conflict and security | Artisanal and small-scale mining | ||

| Conflict-affected and high-risk areas | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bux, C.; Geatti, P.; Sebastiani, S.; Del Chicca, A.; Giungato, P.; Tarabella, A.; Tricase, C. Toward an Experimental Common Framework for Measuring Double Materiality in Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146518

Bux C, Geatti P, Sebastiani S, Del Chicca A, Giungato P, Tarabella A, Tricase C. Toward an Experimental Common Framework for Measuring Double Materiality in Companies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146518

Chicago/Turabian StyleBux, Christian, Paola Geatti, Serena Sebastiani, Andrea Del Chicca, Pasquale Giungato, Angela Tarabella, and Caterina Tricase. 2025. "Toward an Experimental Common Framework for Measuring Double Materiality in Companies" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146518

APA StyleBux, C., Geatti, P., Sebastiani, S., Del Chicca, A., Giungato, P., Tarabella, A., & Tricase, C. (2025). Toward an Experimental Common Framework for Measuring Double Materiality in Companies. Sustainability, 17(14), 6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146518