Abstract

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are increasingly called upon to both respond to and drive societal change. To better understand how HEIs can enhance their ability to innovate, an integrative literature review was conducted, examining the concept of innovative capacity. Key resources, such as social capital and leadership, that support innovative capacity were identified, and the ways in which these key resources interact to give rise to innovation outcomes were explored. The findings were synthesized in a conceptual framework that illuminates the pathways through which the capacity for innovation can be built and leveraged by HEIs. This framework serves as both a theoretical foundation for future research and a practical guide for HEI leaders and policymakers seeking to foster innovation. By leveraging these insights, HEIs can better navigate the challenges of a rapidly evolving society and reinforce their role as key drivers of knowledge creation and the complex societal transformations necessary for a sustainable future.

1. Introduction

The world is facing expanding waves of disruptive changes where the need to adapt to these changes to deal with our present and prepare for the future is indispensable [1]. Rapid changes, such as advancements in technology or growing diversity in perspectives, often demand swift adjustments in higher education institutions. For example, the rapid switch to remote teaching and learning necessitated by global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of AI influencing student learning demonstrate the importance of HEIs ability to be agile and responsive [2]. The capacity to be responsive is needed to adapt to emerging challenges and address immediate needs [3]. HEIs not only have to adjust their own practice, but they also play a pivotal role in shaping and sustaining societal progress, making their ability to respond to societal changes both reactively and proactively essential [4]. Innovative capacity is needed, not only to adapt to the rapid pace of societal change but also to take a proactive role in guiding the transformations necessary for a sustainable future [4] by the missions of teaching, knowledge generating, and the so-called “third mission” of contributing to society at large [5].

HEIs are uniquely positioned to proactively guide and shape the future of society [6] by anticipating long-term trends through research and knowledge creation. For instance, by proactively addressing climate change through research and innovative practices, HEIs can contribute to long-term solutions by taking a leadership position in societal developments [7]. Effective and sustainable innovation builds on a balance between reacting to current needs and anticipating future challenges. HEIs that can adeptly navigate this balance are better equipped to fulfill their mission of being innovative organizations that address complex societal challenges. HEIs thus have a pivotal role as change agents in society driving innovation. Recent systematic literature studies highlight this evolving role in addressing societal challenges and offer insights into the changing functions and responsibilities of HEIs [8,9].

However, despite the pressure rising in society for HEIs to become more innovative, in most education institutions change occurs slowly [10] or is ineffective [11,12]. Both researchers and policymakers stress the need to strengthen the innovative capacity of HEIs [13,14]. The concept of innovative capacity (IC) underscores the ability of organizations to manage their resources (e.g., human and social capital) in ways that foster effective and sustainable innovation [15,16]. Yet despite its significance, the notion of innovative capacity remains ambiguously defined, leaving a critical gap in understanding what it means for an organization to possess the capacity to innovate and what elements enable them to do so [17,18].

Another issue to put forward is that driving educational change depends on different elements in the system, such as the readiness, capacity, and alignment of individuals, teams, and organizational structures and cultures [19]. In other words, the innovative capacity of HEIs encompasses a complex in interplay of abilities at different levels of the organization. Mumford and Hunter [20] point out that successful innovations are often hindered by the lack of connection between different levels of the system; therefore, innovation in organizations should be studied from a multi-level perspective. The authors argue that innovation is influenced by complex interactions among resources operating at and between different levels of analysis, from the individual to the collective and organization. However, innovative capacity cannot be fully understood and explained by mapping these resources. Innovation outcomes in organizations are (trans)formed through mechanisms in a dynamic process [21]. Innovative capacity thus encompasses a complex interplay between reactivity and proactivity and between resources and mechanisms at the individual, network, and organizational level.

This complexity underscores a key challenge for higher education institutions: despite the recognized importance of innovation, fostering and sustaining the innovative capacity of higher education institutes remains a persistent struggle. Therefore, it is necessary to define the concept of innovative capacity (IC) and to gain insight into the resources that enable innovation, as well as the mechanisms through which innovation processes unfold, with the aim of enhancing the innovative capacity of higher education institutions (HEIs). Investigating resources and mechanisms offers a framework for identifying opportunities to enhance innovative capacity and address barriers. The following research questions are hence put forward:

RQ1.

How can the concept of innovative capacity be defined for Higher Educational Institutions?

RQ2.

What are the resources that influence the innovative capacity of Higher Educational Institutions at the individual, network, and organizational levels and how do they interact?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Higher Education Institutes as Driver for Innovation

HEIs have a distinctive role in driving innovation through the creation of knowledge and the promotion of interdisciplinary collaboration. Their innovative capacity hinges on their ability to generate, nurture, and apply new ideas, technologies, and processes that address societal challenges and create value [22] combined with their ability to internally adapt their own teaching and research to a changing environment. Central to this capacity is the cultivation of individual resources, such as critical thinking, creativity, resilience, and an entrepreneurial mindset [23] by providing an environment that supports innovation [24]. These individual resources need to be shared and combined within and across the boundaries of individuals and organizations. Networks can transform individual resources into an amplified, collective power by fostering collaboration, trust, and mutual support. It accelerates the exchange of knowledge and encourages the kind of creativity and problem solving necessary for genuine innovation [25]. Most societal challenges are complex, wicked problems. Networks are not just advantageous but essential for solving complex problems and turning novel ideas into impactful realities [26].

Different elements at the individual (e.g., resilience), the network (e.g., trust), and the organization level (e.g., culture of innovation) form the conditions that can support or hinder the innovative capacity dynamic process [21]. The innovative capacity of HEIs is thus a multifaceted construct shaped by the interplay of conditions and mechanisms operating at different levels of the system: the individual, network, and organization. In the following sections, these levels will be examined in greater detail. First, however, the concept of “innovative capacity of HEIs” will be explored to provide conceptual clarity to the field, as the current literature reveals ambiguity surrounding these terms.

2.2. Innovative Capacity in Higher Education Institutes

To explore the concept of innovative capacity, it is necessary to establish a clear understanding of innovation itself. In the public sector, innovation can be defined as the implementation of a novel concept—whether technical, organizational, policy-related, institutional, or otherwise—that significantly enhances the sector’s functioning and outcomes, thereby generating public value [27]. Innovation involves the introduction of new ideas, practices, or objects that are perceived as original by individuals or organizations [28]. Unlike incremental improvements that refine existing patterns and routines, innovation represents a fundamental disruption of established ideas, beliefs, or practices, leading to a break from the past [29,30].

Building on Gieske et al. [31], four key characteristics of innovation in HEIs emerge: first, innovation is imperative rather than discretionary; second, its success is determined by effective implementation rather than the mere generation of new ideas; third, both individual contributors and the organization as a whole play a crucial role in the innovation process; and fourth, innovation entails radical shifts that break from established practices and beliefs.

In contrast with mere innovation, innovative capacity in education extends beyond the ability to achieve innovation outcomes; it also encompasses the capability to drive and sustain change processes. This includes fostering a learning culture, developing organizational policies, and creating structures that support innovation [24]. In other words, the ability of HEIs to innovate is intrinsically linked to their capacity to cultivate and embed behavioral routines that sustain innovation. These routines enable institutions to manage innovation internally, ensuring adaptability and resilience in a rapidly evolving environment [32]. Strengthening innovative capacity is therefore essential for HEIs to maintain their role as drivers of innovation.

Innovative capacity is a comprehensive organizational ability that enables institutions to achieve their objectives and adapt to dynamic environments. It encompasses a broad range of resources and conditions, including human capital, physical infrastructure, financial resources, social relationships, and operational systems [33]. Soparnot [6] identifies three critical dimensions of innovative capacity: (a) context, which shapes the conditions in which innovation occurs; (b) processes and strategies, which determine how innovation is pursued; and (c) the learning dimension, which reflects an organization’s ability for self-reflection and continuous improvement.

Similarly, Buono and Kerber [33] highlight three central elements influencing innovative capacity: organizational members, structure, and culture. Organizational members play a crucial role, as innovation depends on their readiness and ability to embrace change. Structure refers to the development of an infrastructure that supports change, including leadership, governance, and the allocation of necessary resources. It also involves the presence of networks within the organization and opportunities to participate in external networks, recognizing that innovation is rarely achieved by a single individual. Finally, organizational culture, shaped by shared values and norms, is pivotal in fostering innovation, collaboration, and resilience. By integrating these elements, HEIs can enhance their innovative capacity, ensuring their long-term effectiveness in an increasingly complex and uncertain landscape.

2.3. Exploring Resources and Mechanisms for Innovative Capacity

To describe innovative capacity in HEIs and identify the factors that influence it, a conceptual framework is required. This framework must integrate key dimensions, including the development of people, organizational structures, and institutional culture, while also accounting for contextual influences and strategic processes. The framework also needs to contain mechanisms as the connective processes that link these dimensions, shaping how they interact and influence one another.

There have been various ways of understanding what “mechanism” means in evaluation studies. Astbury and Leeuw [34] define mechanisms as “underlying entities, processes, or structures which operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes of interest.” Dalkin et al. [35] clarify the concept of “mechanism” by distinguishing resources. Resources refer to components that are introduced into a specific context. To clarify how these resources function within a given context, Dalkin et al. [35] emphasize the interaction between resources in producing specific outcomes. Resources encompass both tangible and intangible assets or tools, such as policies, practices, or technologies, which are brought into the organization. The outcome, then, represents the change in behavior, organizational performance, or results that arise from the interaction between the resources. This approach highlights how the interplay between components helps shape the innovation process and generate desired outcomes. In this review we will use the concept of “resources” to refer to these components.

A mechanism can be defined as the underlying process or structure that links resources within a system, shaping their interactions and influencing outcomes. In the context of innovative capacity in HEIs, mechanisms operate as the dynamic relationships that connect people, organizational structures, and institutional culture with contextual influences, strategic processes, and learning mechanisms. These mechanisms enable and regulate the way innovation unfolds, determining how various resources interact to drive or hinder change.

Chen [36] identifies two main mechanisms: mediating mechanisms and moderating mechanisms. Mediating mechanisms are a part of a program that connects two other components and helps explain how one leads to the other. Moderating mechanisms affect the relationship between different program components by introducing a third factor that either strengthens, weakens, or changes the connection. Kessener and Van Oss [37], in addition, distinguish multiple forms of mechanisms; influential relations can be linear (A influences B), a feedback relation (A influences B and B influences A), or circular/non-linear (A influences B directly but also via C and D). These relations determine the characteristics of the system. In complex dynamic systems like HEIs, circular causal relations are common [38].

Innovative capacity is shaped by interdependent resources and mechanisms interacting at multiple levels of the system hierarchy. To gain a full understanding of how innovation unfolds within HEIs, the underlying resources and their interactions must first be unraveled before the mechanisms that explain these interactions can be examined. In other words, the system’s behavior must be mapped prior to studying the mechanisms and considering possible interventions to influence that behavior.

2.4. The Individual Level

What is needed for effective innovation within the public sector has been elaborated on by several authors, thereby acknowledging that the multi-level character of innovation processes must be taken into account [31]. Obviously, individuals play a key role in the innovative capacity of HEIs as organizations are formed by the individuals within. Successful innovation depends on resources at the individual level such as the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of individual teachers, leaders, and supporting staff [39]. Individual resources are transformed through mechanisms, such as knowledge creation or problem solving [40]. However, individuals in HEIs are generally wary of changes that challenge old assumptions and require new skills to succeed [10].

Understanding the IC of HEIs requires a fine-grained insight into the resources and mechanisms at the individual level that hinder innovations. The review by Thurlings et al. [41] showed that previous studies have mainly focused on investigating and explaining individual innovative work behavior, which mainly focuses on resources needed to change teachers’ practices within their own classroom. Innovations at the organizational level will likely require other resources and mechanisms and depend on more than behavior only. A scoping review by Rorije and Vanlommel [23] identified four important categories explaining individual innovative capacity: (a) inquisitiveness, (b) creativity, (c) resilience, and (d) entrepreneurship. Their results show that dispositions, such as commitment, are also important influencing factors.

From a systems perspective, the individual level is a crucial part of the HEIs’ innovative capacity, as individuals serve as the primary agents of innovation within a network of relations and interactions. Individuals are the originators of new ideas, solutions, and approaches that fuel innovation. Their cognitive diversity, personal experiences, and problem-solving abilities provide the resources for innovation. However, individual capacity is a necessary but insufficient resource for driving innovation in HEIs. Individual capacity needs to be amplified, supported, and refined through mechanisms such as knowledge creation or shared decision-making within professional networks [25].

2.5. The Network Level

Many HEIs are moving to more network-based organization principles because it facilitates collaborative learning for innovation and the combined skills and resources of professionals strengthen innovative performance [42,43]. A broad array of literature underpins the importance of networks for innovation through enhanced access to knowledge, complementary resources, and capabilities otherwise not available to the individual [44]. Social capital can be defined as a relational resource that is not located in the actors but in the modalities of their relationships and ties with other individuals. Social capital theory describes how (HE) organizations can access resources through networks [45]. For example, boundary crossing enables individuals to combine diverse skills, perspectives, and knowledge, producing outcomes that surpass what any individual could achieve independently [46]. Collaboration within teams fosters the generation of ideas that are more complex, refined, and impactful [47] Network relationships should be moving from mechanisms of cooperation to collaboration and value co-creation [48].

The interorganizational or network level must be considered when analyzing public sector innovation, as is the case in HEIs. Public organizations operate within complex networks of organizations and their possibilities for developing and applying innovations depends highly upon the characteristics of these networks [49,50]. Individuals in the networks can be supported by organizational resources, and how easily the new knowledge that is constructed in the networks can be adopted in the organization of the individual is dependent on the resources and mechanisms at the organizational level.

2.6. The Organizational Level

An organization is more than the sum of its individuals and networks. Resources at the organizational level are constructs that comprise properties of an organization, such as structures, processes, cultures, and collective dynamics that shape behaviors and innovation outcomes [51]. Organizational resources can amplify or constrain individual capacities, creating environments that either foster or inhibit innovation [31]. For example, a culture that encourages experimentation, risk-taking, and open communication motivates individuals to share and develop new ideas, while a shared organizational purpose aligns these ideas with broader institutional goals [52,53]. Other organizational resources, such as access to funding, training programs, or reward systems, significantly influence individual dispositions by shaping their willingness and ability to engage with and contribute to innovation. Conversely, the lack of supporting resources exacerbates barriers such as fear, uncertainty, or apathy, thereby hindering individual contributions and limiting the institution’s overall ability to innovate [18].

Various mechanisms at the organizational level influence the relation between resources and the success or failure of innovation. For example, collective learning, paired with positive reinforcement systems, fosters a perception of change as an opportunity, enhancing individuals’ willingness to engage. Mechanisms at the organizational level can create and configure relations within and between networks to increase efficiency, productivity, creativity, and processes of knowledge creation. Innovations largely depend on the organizational capacity to cross and span the boundaries of individuals, departments, and organizations [54], especially throughout the university’s own region [5]. Boundary crossing can serve as a mechanism that transforms social capital into innovative outcomes [55]. Yaqub et al. [44] refer to “relational creativity” as a dynamic mechanism in organizations that constantly creates, acquires, or combines resources in an agile manner, facilitating the generation of innovative ideas as well as responding to environmental constraints in novel ways.

Thus, resources and mechanisms at the organization level can empower, energize, and support individuals and can function as a multiplier for individual innovative potential by providing the systems, culture, and resources necessary to sustain and amplify innovative behaviors. Conversely, in HEIs where resources and mechanisms are not in place or aligned, even highly innovative individuals may find it challenging to drive effective change.

In summary, the innovative capacity of HEIs is shaped by resources and mechanisms at the individual, network, and organizational levels. However, existing research on these elements remains fragmented, lacking a cohesive understanding of how they interact. To address this gap, our review synthesizes current insights and integrates them into a comprehensive theoretical framework.

3. Method

To answer the research question, an integrative literature review [56] was conducted. This research method aims at reviewing literature to make a substantive contribution to new knowledge by developing new frameworks and/or perspectives on a certain topic. This method was selected because of the need for defining the concept of IC and understanding the resources and mechanisms influencing the IC of HEIs. The synthesis of literature is a key element of integrative literature reviews [57]. This is a creative process with the literature of the review being the data, combining the methodologies of a systematic literature review with qualitative data analysis [56,57].

3.1. Data Collection: Literature Review in Three Steps

This literature review aimed at defining and understanding the concept of the IC of HEIs. The following research questions were central to the study:

RQ1. How can the concept of innovative capacity be defined for Higher Educational Institutions?

RQ2. What are the resources that influence the innovative capacity of HEIs at the organizational level, the network level, and the individual level and how do they interact?

The literature was systematically searched at the three levels. Every investigation was performed in six online databases: Web of Science (core collection) and five EBSCOhost databases (MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo, ERIC, Education Research Complete, and Teacher Reference Center).

3.1.1. Search 1: Organizational Level

For the first search the following Boolean string of search terms was used [58]: ab = ((higher education institutions OR higher education organizations) AND (change capacity or innovation capacity OR absorptive capacity or organizational performance OR reform capacity OR adaptive change OR transformative capacity OR adaptability OR adaptable capacity)). The search was delimited to peer-reviewed records published in English. In addition, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (a) studies focusing on other educational levels than higher education; (b) studies conducted outside Europe, the United States of America, Canada, and Australia; (c) educational quality instead of innovative capacity as the dependent variable; (d) sustainability in terms of climate sustainability as the dependent variable; and (d) studies that focus on external influences on the IC of the HEI.

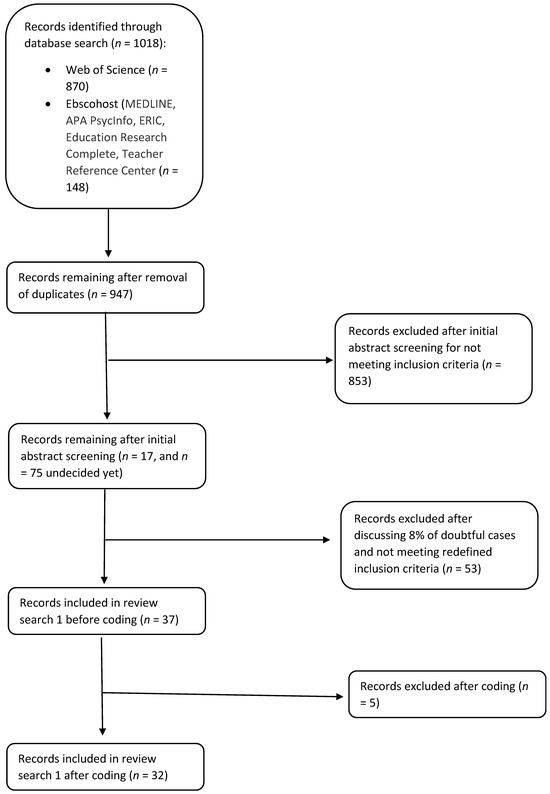

Figure A1 (Appendix A) outlines the entire search process for search 1 according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) guidelines [59]. As shown in Figure A1 the initial searches in the Web of Science and EBSCO databases resulted in 1.018 results. These results were uploaded to the Rayyan platform [60]. After removing the duplicates present in the different databases (as indicated by Rayyan), 947 papers remained. After screening the abstracts, and, if needed, full texts, 853 papers were excluded. Initially, 17 papers were included, while the remaining 75 papers posed difficulties in determining their suitability. Hence, the research team discussed 8 (i.e., 10%) of these abstracts. This discussion resulted in additional inclusion and exclusion criteria that were applied to the remaining 75 papers. The additional exclusion criterium was studies that presumed that their results might also have an effect on IC but did not investigate that presumption. The additional inclusion criterium was if the dependent variable was related to innovative capacity (for example, the degree of meeting the criteria of being an entrepreneurial university, adaptive change, or learning organization). This resulted in the exclusion of another 53 papers. In total, at the organizational level, 37 studies were selected for analysis.

3.1.2. Search 2: Network Level

The search string used for the second search was as follows [58]: ab = ((higher education institutions OR higher education organizations) AND (change capacity or innovation capacity or absorptive capacity or organizational performance or reform capacity or adaptive change or transformative capacity or adaptability or adaptable capacity)) AND (network or networked learning OR innovation network). The search was limited to peer-reviewed records written in English and the same exclusion criteria applied as in search string 1, with the addition of a timeframe spanning 2014–2024 to promote relevance. Articles were discussed in the research group. Articles that focused solely on student networks for educational purposes, on primary or secondary education, or not focusing on the HEI level were removed, as were articles without definitions, resources, and mechanisms concerning networks and innovative capacity. This resulted in the inclusion of 45 articles to be analyzed.

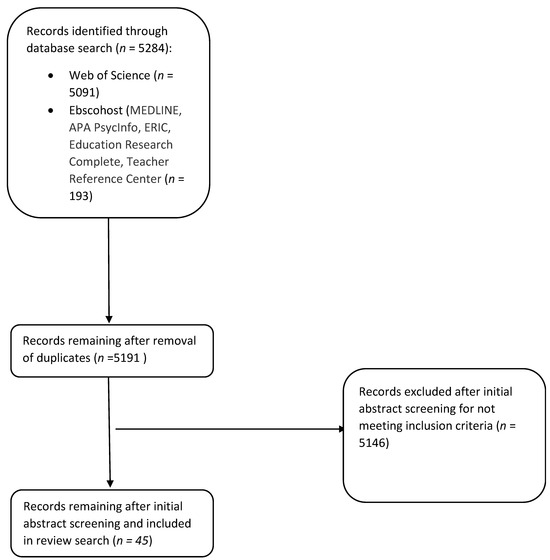

Figure A2 (Appendix A) outlines the entire search process for search 2 according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) guidelines [59]. As shown in Figure A2 our initial searches in the Web of Science and EBSCO databases resulted in 6187 results. These results were uploaded to the Rayyan platform [60]. After removing the duplicates present in the different databases (as indicated by Rayyan), 6091 papers remained. After screening the abstracts, and, if needed, full texts, 5806 papers were excluded. As a result, 45 papers were included in this study.

3.1.3. Search 3: Individual Level

The search string used for the third search was as follows [58]: ab = ((((Innovative behavio* OR Innovative work behavio* OR Teacher leader OR Change agent OR Agency OR Innovative capa* OR Innovative strength OR Transformative capa* OR Capacity for change OR Change capa* OR Change competen*) AND (Teacher* OR Educational Professional OR Teacher leader OR Change agent OR Reflective practitioner) AND (Educational Change OR Innovation in Education OR School Reform OR School Change OR Educational Innovation OR Improving learning) AND (Higher Education Institution OR Higher Education Organi* OR university OR higher vocational education)))).

The search was delimited for peer-reviewed records written in English. In addition, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (a) studies focusing on other educational levels than higher education; (b) studies conducted outside Europe, the United States of America, Canada, and Australia; (c) not investigating individual innovative capacity; and (d) not investigating the relationship between individual innovative capacity and the innovative capacity of the HEI.

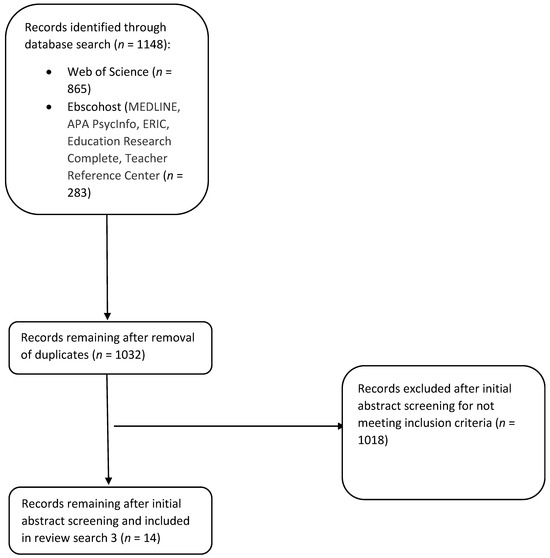

Figure A3 (Appendix A) outlines the entire search process for search 3 according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) guidelines [59]. As shown in Figure A3 the initial searches in the Web of Science and EBSCO databases resulted in 1.148 results. These results were uploaded to the Rayyan platform [60]. After removing the duplicates present in the different databases (as indicated by Rayyan), 1032 papers remained. After screening the abstracts, and, if needed, full texts, 1018 papers were excluded. As a result, 14 papers were included in this study.

Searches 1, 2, and 3 together resulted in 96 articles that were analyzed, although one article appeared in two searches; hence, the total number of articles was 95.

3.2. Data Analysis: ATLAS.ti

Following Toracco [56,57], to ensure transparency and replicability, the process of analysis is described in detail. The data was analyzed in several rounds. To identify units of analysis, saliant concepts from our research questions were defined first within the research group to ensure a shared understanding. These definitions were used to retrieve definitions and resources from over 70% of the included articles (n = 80). Subsequently, the units of analyses were coded inductively in an iterative process in ATLAS.ti to identify concepts (first-order concepts), themes (second-order themes), and key categories [56,57,61,62] by four researchers. The differences were discussed between all four researchers until consensus was reached using the consensus coding approach [56,57,63]. Following the inductive coding phase, the overarching themes and key categories were identified in the selective phase, using again the consensus coding approach, resulting in seven key categories and concept definitions of these resources and of the concept “innovative capacity”. The concept definition of IC was formulated first by the four researchers separately (based on the quotations with the label “definitions IC”) and combined into a concept definition by means of a discussion within the research group to find consensus of the defining elements of the IC of HEIs. The concept definitions of the seven resources were derived from the research analyzed in this first round that defined these resources in their articles.

In a second round the 80 articles were coded again on these seven resources (i.e., axial coding). The remaining 22 articles that were coded for the first time were also coded on these seven resources, with the possibility to add new resources, if necessary. This led to the exclusion of 5 more organization-level articles because no coding on IC or the resources could be performed and these articles also did not provide new definitions or resources of IC, resulting in a final sample of 91 articles. In the third round, the concept definitions of IC and the seven resources were sharpened and enriched by reviewing all the relevant codes. Refinement of the coding and the definitions was discussed between two researchers until agreement was reached.

To gain insight into the mechanisms between resources and IC, all the coded resources were recoded in a new round of coding to find relations of influence between the resources and between the resources and IC in the quotations throughout all three levels. The relations between resources and IC were solely coded as influential since the nature of the influence was often not specified. The mechanisms were coded by one researcher and recoded by the second. The differences were discussed until agreement was reached using again the consensus coding approach [63]. The mechanisms were analyzed based on frequency to find both driving and ambivalent factors within the resources that support the innovative capacity of a higher education institution. The driving factor is considered an element within a system that, through leverage, can have a significant impact on the entire system with minimal effort. These factors mainly influence other factors but are hardly influenced themselves; they form a good pointer for change [64]. An ambivalent factor is an element that is decisive for the success or failure of a process, project, or system. These are factors that influence other factors as often as these themselves are influenced by other factors. Because of their interconnectedness, they do not form a logical starting point to lever innovative capacity [64].

Finally, the influential relations between resources were visualized in a diagram resulting in an overview of how resources influenced each other to stimulate and facilitate IC. This diagram aided into analyzing the paths of influence between resources within an organization and resulted in the proposed conceptual framework of mechanisms affecting the IC of HEIs.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptives of the Final Sample

Before answering the research questions, the characteristics of the included studies per search were described at the organizational (n = 32), network (n = 45), and individual level (n = 14) as shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

4.1.1. Organizational Level

The studies on the organizational level described the role of higher education institutions (HEIs) in addressing sustainability, innovation, and regional development. They showed that current academic structures often fall short in enabling the transition to sustainable and entrepreneurial societies. Key challenges included the need for institutional reform, better integration of sustainability in education, and improved knowledge transfer—particularly in systems where universities and colleges serve different but complementary roles. Despite financial and structural barriers, initiatives promoting innovation mindsets, interdisciplinary collaboration, and practical engagement with industry and society demonstrated promising pathways forward. Successful transformation depended on long-term vision, collaboration, adaptability, and embedding sustainability into everyday academic processes.

Table 1.

Coded resources within studies at organizational level.

Table 1.

Coded resources within studies at organizational level.

| Structural Capital | Leadership | Collective Networked Learning | Social Capital | Lived Mission/Vision | Human Capital | Organizational Culture | Innovative Capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [65] | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |||

| [66] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| [67] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| [68] | 2 | |||||||

| [69] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||

| [70] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| [71] | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | ||||

| [72] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| [73] | 4 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| [74] | 1 | |||||||

| [75] | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| [76] | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| [77] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [78] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| [79] | 11 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| [80] | 1 | |||||||

| [81] | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |||

| [82] | 1 | |||||||

| [83] | 4 | 3 | ||||||

| [84] | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| [85] | 3 | |||||||

| [86] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| [87] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [88] | 1 | |||||||

| [89] | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| [90] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| [91] | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| [92] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||

| [93] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [94] | 1 | |||||||

| [95] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [96] | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 50 | 15 | 34 | 17 | 31 | 22 | 11 | 68 |

Table 1 presents an overview of the coded resources identified in the studies at the organizational level. Notably, structural capital was mentioned most frequently across the reviewed articles.

In contrast, leadership, human capital, and organizational culture were referenced less often. In many articles different combinations of coded resources were found to be important for innovative capacity.

4.1.2. Network Level

The studies on the network level discussed various aspects of knowledge transfer, innovation, and quality culture within higher education, particularly in the context of educational leadership and institutional development. The focal points ranged from educational trajectories such as health professional education and agricultural education to fundamental research, sustainability, and innovation. Table 2 presents an overview of coded resources related to innovative capacity as identified in the studies at the network level. Social capital was mentioned most frequently in the reviewed articles, next to collective networked learning. Leadership, organizational culture, and lived mission/vision were mentioned less often.

Table 2.

Coded resources within studies at network level.

Table 2.

Coded resources within studies at network level.

| Structural Capital | Leader-Ship | Collective Networked Learning | Social Capital | Lived Mission/ Vision | Human Capital | Organizational Culture | Innovative Capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [97] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [98] | 1 | |||||||

| [99] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| [100] | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| [101] | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| [102] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| [103] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| [104] | 1 | |||||||

| [105] | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| [106] | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| [107] | 1 | |||||||

| [13] | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| [108] | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| [109] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [110] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| [111] | 4 | 7 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| [112] | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| [113] | 1 | |||||||

| [77] | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 8 | |

| [114] | 1 | |||||||

| [115] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [116] | 1 | |||||||

| [117] | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |||

| [118] | 3 | |||||||

| [119] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [120] | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||

| [121] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| [122] | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| [123] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| [124] | 1 | |||||||

| [125] | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| [126] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [127] | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| [128] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| [129] | 1 | |||||||

| [130] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| [131] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| [132] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| [133] | 1 | |||||||

| [134] | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| [135] | 1 | |||||||

| [136] | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| [137] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| [138] | 2 | |||||||

| [139] | 1 | |||||||

| [140] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 35 | 12 | 40 | 61 | 10 | 25 | 14 | 37 |

4.1.3. Individual Level

At the individual level, the studies explored various aspects of educational change and innovation in higher education. They emphasized the importance of supportive environments and targeted strategies for fostering innovation, curriculum development, and gender equality. Key findings highlight that innovation in education was most effective when supported by management; exposure to new ideas; and a diverse, collaborative environment. Educational developers and leaders played critical roles as change agents, with their influence being shaped by how their roles are perceived and how educational reforms are structured. Table 3 presents an overview of the coded resources related to innovative capacity as identified in the studies at the individual level. Human capital was mentioned most frequently in the reviewed articles. Organizational culture, lived mission/vision, and social capital were mentioned less often.

Table 3.

Coded resources within studies at individual level.

Table 3.

Coded resources within studies at individual level.

| Structural Capital | Leader-Ship | Collective Networked Learning | Social Capital | Lived Mission/ Vision | Human Capital | Organizational Culture | Innovative Capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [141] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| [142] | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 | |||

| [143] | ||||||||

| [144] | 12 | |||||||

| [145] | 2 | 10 | 8 | 7 | ||||

| [146] | 4 | |||||||

| [147] | 2 | 1 | 12 | |||||

| [148] | 1 | |||||||

| [149] | ||||||||

| [150] | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| [151] | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| [152] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| [153] | ||||||||

| [154] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 9 | 13 | 12 | 4 | 5 | 55 | 4 | 20 |

4.2. Defining the Innovative Capacity of HEIs

The first research question aimed at understanding how the innovative capacity of HEIs can be defined. A total of 157 text segments were coded as (partly) defining the concept of “innovative capacity”. One of these text segments is of Sciarelli et al. [94] below.

“Innovation in HEIs can be understood as those procedures and methods of educational activity that differ from established ones and that can increase the university efficiency level in the competitive environment. It is the capability of the institution to introduce new academic programs, curriculums, teaching methods and the like to be more competitive in a turbulent environment.” [94]

This text segment defines innovation in higher education institutions and the capacity that leads to these innovations. Text segments like these were qualitatively analyzed and subsequently synthesized. Different elements were identified and brought together based on a subset of the literature to formulate a concept definition. This concept definition was refined and enriched based on the rest of the literature by means of discussions between two researchers of the research team until agreement was reached.

Concepts that were included in the definition were based on their occurrence. The concept of innovation occurred 202 times in several different concepts that were thematically linked: innovation (88), innovative (22), innovations (10), change (35), changes (25), changing (4), transformation (4), transformational (6), novel (4), and solutions (4). Strategic and reflexive capacity occurred 74 times and was synthesized from concepts such as capacity (14), capabilities (12), capability (4), adaptability (11), agility (10), strategic (10), strategy (6), and policies (7).

This way of working resulted in thematic clustering as depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

Thematic clustering of concepts in defining innovative capacity.

This resulted in the following definition of the innovative capacity of HEIs:

Innovative capacity is the strategic and reflexive capacity of the higher education institution to anticipate and predict changes, internally, within the organization, and externally within society, to formulate and reach shared educational, scientific, and societal goals to create and implement knowledge, span boundaries, and create networks within and between organizations, actively shaping changes in educational, scientific, and administrative processes to successfully integrate and use innovations in HEIs and society.

4.3. Resources That Affect the Innovative Capacity (IC) of HEIs

To answer the second research question (what are the resources that influence the innovative capacity of HEIs at the individual, network, and organizational level and how do they interact?), axial coding was conducted and resulted in seven resources that affect the IC of HEIs: collective networked learning, leadership, organizational culture, lived mission/vision, human capital, social capital, and structural capital. Reviewing and synthesizing all the text segments referring to these seven resources, using the same approach as the concept of innovative capacity, resulted in the following definitions:

4.3.1. Collective Networked Learning

Collective networked learning is the active focus on the construction of networks within and outside HEIs, the presence of networks within HEIs, and the participation of individuals in networks within HEIs, resulting in collective cognition, which includes change agency, shared knowledge within the network, and the communication structure within the network, and the construction of high-quality knowledge to be shared outside the network.

4.3.2. Leadership

Leadership is an organizationally acknowledged construct, with the aim and responsibility to initiate, facilitate, and endorse changes and innovations, for instance, by creating safe spaces, a learning culture, and formational (e.g., positioning others) and adaptable structures and showing transformational leadership behavior.

4.3.3. Organizational Culture

Organizational culture consists of constantly evolving identity-shaping beliefs and structures, mediated by trust and transparency, transmitted through learning, that form the blueprint of the day-to-day functioning of an organization regarding the promotion of knowledge sharing, knowledge creation, diversity, and the willingness to adapt and innovate. These beliefs are supported by the mission, vision, attitudes, and values of the organization; performance indicators; the position of authority; the actual power basis; decisional capital; the type of leadership; and ways of evaluating and motivating staff.

4.3.4. Human Capital

Human capital refers to the support, means, and capacities, such as knowledge, skills, and strategies, educational professionals need to successfully function to achieve organizational goals and improve practice. These capacities can be categorized as knowledge construction, network literacy, and change agency.

4.3.5. Lived Mission and Vision

A lived mission and vision of an organization refers to the degree to which the organization’s mission and vision finds broad acceptance among individuals within the organization. It is the degree to which members of an organization (entity) agree on a vision for the future, shared goals, and strategy, which can then form the basis for their action.

4.3.6. Social Capital

Social capital is the combination of actual and potential resources, cognitive, relational, and structural, that are constructed by relations of individuals with others, and by interorganizational relations, and the quality of such relations in terms of trust, reciprocity, respect, obligations, and even friendship.

4.3.7. Structural Capital

Structural capital refers to the internal processes of dissemination, communication, and management of scientific and technical knowledge within an organization.

Structural capital includes the following:

- (1)

- Structures—the infrastructure: (monitoring) systems, processes, spaces, databases, and other forms of codified knowledge that support the activities and operations of a business or organization as well as the elimination of barriers, paving the way to access to strategic resources.

- (2)

- Governance—the clear delegation of authority and responsibilities.

- (3)

- Designed (learning) processes—the policy and structures that stimulate and facilitate learning and change within the organization.

- (4)

- HR reward systems and resources—aimed at knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, and long-term capacity building for multi-stakeholder partnerships.

Table 5 shows how often these codes occurred in the studies on each of the three levels. On the organizational level of HEIs, structural capital was most often coded as a resource for innovative capacity. On the network level social capital was most often coded; on the individual level human capital played a central role.

Table 5.

Resources affecting IC on organizational, network, and individual level.

4.4. Interacting Resources

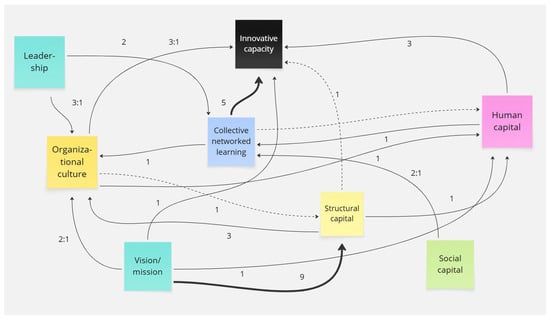

In addition to examining the influence of different resources on IC, the interactions among these seven resources at the various levels were analyzed (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), as well as their aggregation across all three levels (see Figure 4).

4.4.1. Interacting Resources at the Organizational Level

At the organizational level, the lived vision/mission of the organization, leadership, and social capital are driving factors, influencing other resources but not being influenced. The lived vision/mission of the HEI influenced human capital, organizational culture, and the innovative capacity of the HEI directly. Influencing interactions of the vision/mission of the HEI on structural capital were mentioned nine times. The below text segment illustrates how the interaction between the vision and mission of the organization (“strategic planning process”) and innovative capacity (“opportunities for tangible improvements”) is described.

“Strategic plans are the most important vehicle to set expectations and develop performance indicators and targets for the future. Using a strategic planning process, a higher education institution can observe current performance, identify opportunities for tangible improvements, and communicate their current and expected performance both academically and organizationally.” [65]

Leadership influenced collective networked learning and organizational culture. Social capital was only mentioned twice as influencing collective networked learning. Collective networked learning as influencing innovative capacity was mentioned most often, five times. The resources collective networked learning, organizational culture, human capital, and structural capital both influenced other resources and were influenced themselves. The text segment below illustrates several mechanisms between resources. The segment starts with the relation between organizational culture and lived mission/vision, followed by structural capital–organizational culture and human capital–organizational culture.

Organizational culture is supported by the organization’s mission and vision (Wen Chong et al., 2000), and also by the way the processes and managerial practices are devised and carried out; as well as the attitudes and values of the organization (Adeinat & Abdulfatah, 2019), the beliefs that compose their identity such as performance criteria, assessment of the staff and motivation (Ibarra-Cisneros et al., 2023; Mubarak & Sabraz Nawaz, 2019).

Figure 1.

Interacting resources at the organization level. Note. Solid lines represent relationships between individual resources, while dashed lines indicate relationships involving multiple resources. The numbers on the lines denote the total number of identified relationships; numbers following a colon indicate the number of relationships involving multiple resources. Line thickness increases with the frequency of observed relationships.

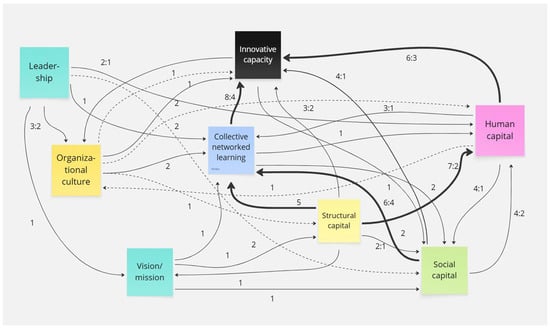

4.4.2. Interacting Resources at the Network Level

Figure 2 shows that at the network level in HEIs, social capital and human capital were most often distinguished as directly influencing the innovative capacity of higher education. Social capital and structural capital both can be considered driving factors, influencing other resources but rarely mentioned as being influenced. When following the lines of influence, structural capital, or the internal processes of dissemination and communication within an organization, appears to be a lever that influences both the collective networked learning that occurs within the HEI and the knowledge and skills of educational professionals, aka human capital. The text segment below shows the interaction mentioned between structural capital and collective networked learning (“the best strategy for policymakers is to create resources for maximal diversity instead of investing in science monocultures”):

“Based on these two approaches—path dependence and novel combinations—it can be assumed that it is above all two aspects that need to be considered when trying to understand or even facilitate innovation: Firstly, innovative changes will only be successful if integrated in existing social and cultural traditions. Secondly, the best strategy for policy makers is to create conditions for maximal diversity instead of investing in science monocultures. Novel combinations connecting different areas can only emerge in a diverse and open academic environment; it is by definition difficult to anticipate these new connections since the productivity of these can often be assessed only in hindsight.” [131]

The actual and potential resources of the HEI, or its social capital, influence both the collective networked learning that occurs and the innovative capacity of the HEI directly. The skills and knowledge of HEI employees also directly influence its innovative capacity, an interaction coded nine times.

Figure 2.

Interacting resources at the network level. Note. Solid lines represent relationships between individual resources, while dashed lines indicate relationships involving multiple resources. The numbers on the lines denote the total number of identified relationships; numbers following a colon indicate the number of relationships involving multiple resources. Line thickness increases with the frequency of observed relationships.

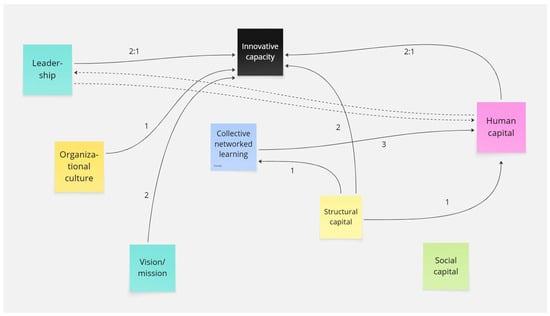

4.4.3. Interacting Resources at the Individual Level

At the individual level of HEIs, only 15 interactions were found. Most influential relations mentioned in the literature led to innovative capacity. The influence of collective networked learning on the skills and knowledge of educational professionals was coded most, being three times. On this individual level, both organizational culture and the lived mission/vision of the organization could be considered driving factors, although the limited number of interacting resources calls for caution in drawing definitive conclusions. There were no influential relations mentioned concerning social capital, although the resource itself was coded four times (cf. Figure 3).

The text segment below shows an interaction between leadership and innovative capacity.

“Jones and Wisker (2012) underline that the effectiveness and success of ADs’ work often appear to depend on support from leaders. The way educational leaders perceive educational change and position ADs seems to matter.”

Figure 3.

Interacting resources at the individual level. Note. Solid lines represent relationships between individual resources, while dashed lines indicate relationships involving multiple resources. The numbers on the lines denote the total number of identified relationships; numbers following a colon indicate the number of relationships involving multiple resources. Line thickness increases with the frequency of observed relationships.

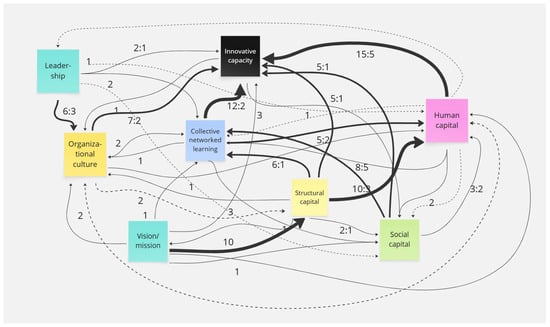

4.4.4. Driving and Ambivalent Resources

The frequency with which resources influenced other resources was examined in comparison to how often they were influenced by others at the aggregated level (combining individual, network, and organizational levels). This analysis identified two types of resources: driving resources, which predominantly influenced other resources but were rarely influenced themselves, and ambivalent resources, which influenced others approximately as often as they were influenced. The number of mentions of resources in interactions—both as influencers and as being influenced—was quantified, resulting in the data presented in Table 6.

As shown in Table 6, leadership, structural capital, and a lived mission/vision emerged as key resources that enhance the innovative capacity (IC) of HEIs. Specifically, interactions originating from leadership and structural capital more frequently led to increased IC compared to those stemming from a lived mission/vision. The remaining resources—collective networked learning, human capital, organizational culture, and social capital—occupied a more ambivalent position, exerting influence on other resources and being influenced in return with similar frequency.

Table 6.

Driving and ambivalent resources.

Table 6.

Driving and ambivalent resources.

| Resource | Influencing | Being Influenced | D/A * | Directly Affecting IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collective networked learning | 21 | 23 | P | 13 |

| Human capital | 24 | 23 | P | 15 |

| Leadership | 13 | 1 | D | 2 |

| Organizational culture | 14 | 13 | P | 7 |

| Structural capital | 27 | 12 | D | 6 |

| Social capital | 16 | 9 | P | 5 |

| Lived mission/vision | 18 | 1 | D | 3 |

* D = driving; A = ambivalent.

Figure 4.

Interacting resources aggregated on organizational, network, and individual level affecting innovative capacity. Note. Solid lines represent relationships between individual resources, while dashed lines indicate relationships involving multiple resources. The numbers on the lines denote the total number of identified relationships; numbers following a colon indicate the number of relationships involving multiple resources. Line thickness increases with the frequency of observed relationships.

Figure 4 illustrates how resources form circles that influence HEI’s innovative capacity. Dashed lines represent interactions that consist of multiple resources. Two numbers divided by a colon indicate the interaction of multiple resources; the last number represents these mechanisms. The driving resource lived mission/vision appears to have some direct influence on innovative capacity, but its influence on structural capital was mentioned ten times. Following the chain of influence, we see that the lived mission/vision influences structural capital, which influences human capital, which in its turn was mentioned 11 times as influential on innovative capacity.

4.5. Synthesis Toward a Conceptual Framework

The aim of the present study was to develop a conceptual framework applicable across all three levels—individual, network, and organizational—to gain insight into the complexity of resources influencing the innovative capacity (IC) of HEIs. As all the identified resources appeared at each of these levels, the data was aggregated to examine interactions occurring across the different levels. To identify potential relationships between resources, all the codes in ATLAS.ti were systematically reviewed to determine whether the co-occurrence of resources within each quotation also implied an influential connection between them. The aggregation of these interacting resources on all three levels resulted in a conceptual framework (see Table 7). This conceptual framework shows how resources influence each other in collectively constructing the innovative capacity of a higher education institution. As can be seen, an interaction sometimes exists between two resources or one resource and IC. These direct relations between a resource and IC are important, but often the interactions were more complex. For example, leadership was found to influence organizational culture, which affected structural capital, which affected IC. Another example of a mentioned complex interaction between resources was structural capital influencing social capital, influencing collective networked learning, which enhanced the IC of the HEI. Human capital affecting IC was preceded by either organizational culture, collective networked learning, or social capital.

Table 7.

Conceptual framework of interacting resources and innovative capacity of HEI.

Table 7 shows how the interactions between resources are distributed among the different levels. A total of 47 interacting resources were identified. Some resources were mentioned only once, others as much as ten times. As Table 7 shows, human capital (9) and collective networked learning (10) were most often mentioned as a direct influence on IC. Structural capital and organizational culture were mentioned as having an influential relation with IC, respectively, four and five times. The below text segment derived from the networked level illustrates the mechanism collective networked learning influencing innovative capacity (CN-IC). This mechanism was coded five times on both organizational and networked level data:

“In order to create successful innovation, HEIs depend on its social networking capabilities such as how they collect resources, facilitate the knowledge dissemination process, and identify opportunities by forming social ties, thus increasing legitimacy for collective action and social innovation process. […] Thus, it is important to understand the ways by which HEIs can enhance their networking capabilities to facilitate co-creation of social innovation.” [117]

As Table 8 shows, most interacting resources were found on the network level. Most influential relations were found between some of the resources; structural capital was the only resource mentioned as influencing all the other resources. Innovative capacity was mentioned twice as influencing other resources: the organizational culture and the social capital of the HEI.

Table 8.

Distribution of interacting resources among different levels.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

The current study pursued two main objectives. First, it sought to address a gap in the literature by defining what it means for an organization to possess innovative capacity (IC), answering the following question: “How can the concept of innovative capacity be defined for higher educational institutions?” Open and axial coding of the selected literature on the concept resulted in an integrated definition of the IC of HEIs, as presented in paragraph 4.2. This definition of innovative capacity emphasizes that changes should not only be actively shaped in educational and scientific processes but also in administrative processes. This fosters the sustainability of the innovations. Next to that, the definition states the integration and use of innovations in HEIs and society. This too points at a sustainable view of innovation. Since HEIs are increasingly embracing their social responsibility in sustainable development, this will go hand in hand with the responsibility to increase their innovative capacity as well.

Second, this study aimed to gain insight into the key resources and the interactions among those resources that enhance the IC of higher education institutions (HEIs) across the individual, network, and organizational levels, as well as their aggregation. The central question was as follows: “What are the resources that influence the innovative capacity of HEIs at the organizational level, the network level, and the individual level and how do they interact?”

Seven key resources were identified affecting the IC of HEIs: collective networked learning, leadership, organizational culture, lived mission/vision, human capital, social capital, and structural capital. These resources were found to be important across all three levels of analysis (individual, network, and organizational). However, at different levels, different emphases were seen in how often the resources were named, possibly because of the nature and context of that specific level. At the organizational level, the resource structural capital was often named, while in the selected literature at the level of networks, social capital and collective networked learning are named most often. At the level of the individual, a very strong emphasis can be seen on human capital. Awareness of this focus on specific resources on the organizational, network, or individual level may offer opportunities to break patterns and deploy new promising resources to further promote innovative capacity. For example, within educational innovation processes, the focus is often on structural capital, while human capital and vision are also very promising resources for the success of the innovation [155]. Definitions of these seven resources were constructed based on the selected literature to ensure conceptual clarity.

In terms of resource interactions, evidence indicates that resources mutually influence one another and collectively impact the innovative capacity of higher education institutions (HEIs). Human capital and collective networked learning were found to have the most direct influence on IC, followed by structural capital and organizational culture. However, the relationships between these resources and IC are often more complex. For example, human capital’s influence on IC is frequently preceded by organizational culture, collective networked learning, or social capital. Leadership, structural capital, and a lived mission and vision were identified as driving factors because they primarily influence other resources without being significantly influenced by them. Interestingly, leadership and structural capital tend to result in IC more directly, whereas a lived mission and vision play a foundational role by guiding the direction of the organization, through influencing structural capital and human capital.

The concept of a “lived mission and vision” is therefore an important resource for the innovative capacity of HEIs. As Bart [156] suggested, having a lived mission and vision requires high-quality mission and vision statements that are co-created with employees and strike a balance between abstract and concrete formulations. A vision helps define the core values and principles that guide daily activities and decision-making within the organization [157]. It also plays a role in building a sense of identity by bringing people together and encouraging their commitment and sense of belonging [158]. In complex institutions like HEIs, where people often work across different roles and departments, a shared vision can help align efforts and reduce fragmentation [159]. In literature on collective knowledge construction, the concept of collective attention, focused by a common ambition and shared values, is crucial in aligning different perspectives for wicked problem solving [47]. Future research could explore the relationship between the quality of mission and vision statements in HEIs, the processes of crafting and implementing these statements, and their impact on the IC of HEIs.

One concept that emerged from the selected literature but could not be distinctly categorized as either a resource or as interacting resources is organizational alignment. It appears that fostering alignment between different resources may enhance the effectiveness of their interactions, thereby contributing to the innovative capacity (IC) of HEIs. Organizational alignment or congruence has been a well-valued factor in the business context to explain organizational success [160]. This suggests that organizational alignment functions as a facilitating factor in the interaction between resources, fostering IC. Our findings also coincide with the dynamic capabilities framework, showing that organizations not only possess resources but also could coordinate and reconfigure them to adapt to changing environments. Organizational alignment can be seen as a crucial factor in this process, as it enhances the effective utilization of existing capabilities [161].

The conceptual framework proposed in this study offers a synthesis of the complex interactions between resources influencing the IC of HEIs. However, since no study has yet examined all the identified resources collectively or explored the specific interactions between them, the framework remains theoretical. Next to that, it seems that research on IC in HEIs has been more commonly conducted at the network level and that research focusing on the interacting resources at the organizational and individual levels remains limited in both quality and quantity. This may be due to the complexity of the subject matter and the lack of a widely accepted definition of IC. Many studies do not define IC explicitly, or they relate it to other concepts like “learning organizations”. Hence, the provided definition of IC in this study may foster a deeper investigation of resources and their interactions at the individual and organizational level to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing IC.

For one thing, studying all seven resources together allows for a more comprehensive view of how they interact and contribute to IC rather than analyzing them in isolation. Future research should further explore the complexity within this framework, for instance, by investigating specific mechanisms identified in this study, for example, by analyzing the path from social capital to collective networked learning to IC, or the influence of leadership on organizational culture and IC. Literature reviews and empirical investigations of practice are necessary to further investigate and refine the understanding of the resources within this framework and especially the nature of the mechanisms that contribute to the IC of HEIs. Secondly, examining the relationships between all seven resources and their impact on IC within a specific HEI would provide valuable insights. Empirical investigation helps confirm whether these assumptions remain valid in real-world settings. Furthermore, it allows us to refine its components and to identify gaps, and it ensures the model’s applicability across diverse higher education environments. Validating the current framework within HEIs, in collaboration with HEI members or experts in educational innovation and organizational science, would be a valuable next step in enhancing our understanding of IC.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of understanding the mechanisms that connect various resources influencing innovative capacity (IC) within higher education institutions (HEIs). Simply mapping the relationships between variables is not sufficient to establish causality or understand the mechanism behind it; it is necessary to delve deeper into the processes that link these variables and explain why certain resources lead to specific outcomes. More important is the acknowledgement that our common idea of linear causality (i.e., A causes B) will not hold in the dynamic complexity of an HEI. Our conceptual framework should be studied with the concept of circular causality (i.e., A causes B and B causes A, or A causes B, B causes C, and C causes A) in mind [38]. For example, innovative capacity was not only influenced by other resources but was also mentioned twice as influencing the organizational culture and the social capital of the HEI.

This study aimed to uncover the “how” and “why” behind the interactions of resources that affect innovative capacity (IC) within HEIs, offering a conceptual framework that highlights an array of interactions between key resources. However, upon analyzing the data, insights into the “how” and “why” were only present to a limited extent. While the resources and their relationships were identified, the deeper processes and underlying explanations were less apparent. To fully understand the interaction between resources, the nature of the mechanisms causing the interactions needs to be studied. For instance, how exactly leadership facilitates and stimulates innovative capacity is unclear. Besides explaining why such a relationship comes about, it is necessary to establish what goes on in the system that connects its various inputs and outputs [35]. In addition, although the resources that come into play in the complex and intertwined processes that constitute innovative capacity are defined, the way they need to be configured to facilitate and stimulate innovative capacity is also still unclear. This suggests that further research is necessary to fully explore and understand both the resources and the mechanisms at play to gain insight into the circles of causality and the levers that can strengthen or diminish the effects.

The proposed conceptual framework represents an initial step toward creating a theory for the IC of HEIs. It provides a foundation for understanding how different resources, such as human capital, leadership, and organizational culture, interact to influence an institution’s innovative capacity. This approach encourages a more holistic view of the resources that contribute to innovation in higher education, focusing not just on isolated resources but on the complex interplay between them. Examining these mechanisms in context enables a clearer understanding of how the innovative capacities required to meet contemporary educational demands are developed and sustained by HEIs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V., L.S., F.N. and M.C.-B.; methodology, F.N. and L.S.; software, F.N.; validation, M.C.-B., F.N. and L.S.; formal analysis, L.S. and F.N.; investigation, L.S., F.N. and M.C.-B.; data curation, F.N. and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V., F.N., L.S. and M.C.-B.; writing—review and editing, L.S., F.N. and M.C.-B.; visualization, F.N.; supervision, L.S.; project administration, K.V.; funding acquisition, K.V., F.N. and M.C.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Netherlands’ Initiative for Education Research (NRO) grant number 40.5.22945.402. The APC was funded by NRO and Utrecht University of Applied Sciences.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Carlijn Zandvliet for her help with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Flowchart of the search and selection process of search 1 (organizational level).

Figure A2.

Flowchart of the search and selection process of search 2 (network level).

Figure A3.

Flowchart of the search and selection process of search 3 (individual level).

References

- Kotter, J.P.; Akhtar, V.; Gupta, G. Change: How Organizations Achieve Hard-to-Imagine Results in Uncertain and Volatile Times; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid Miranda, R.; Glas, K.; Chapman, C. Building agency in school–university partnerships: Lessons from collaborative research during the pandemic. J. Educ. Adm. 2024, 62, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, W.Q.; Elenkov, D. Organizational capacity for change and environmental performance: An empirical assessment of Bulgarian firms. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher education and the sustainable development goals. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compagnucci, L.; Spigarelli, F. The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soparnot, R. The concept of organizational change capacity. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2011, 24, 640–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molthan-Hill, P.; Worsfold, N.; Nagy, G.J.; Leal Filho, W.; Mifsud, M. Climate change education for universities: A conceptual framework from an international study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, D.Y.; Aparicio, J. Introducing a functional framework for integrating the empirical evidence about higher education institutions’ functions and capabilities: A literature review. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2021, 17, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera Trevisan, L.; Leal, W.; Ávila Pedrozo, E. Transformative organisational learning for sustainability in higher education: A literature review and an international multi-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L. Barriers to Innovation and Change in Higher Education; TIAA-CREF Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hubers, M.D. In pursuit of sustainable educational change-Introduction to the special section. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 93, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P. The more things change, the more things stay the same? Educ. Urban Soc. 2012, 44, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosling, G.; Nair, M.; Vaithilingam, S. A creative learning ecosystem, quality of education and innovative capacity: A perspective from higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.F.; Tian, F. Enhancing competitive advantage in Hong Kong higher education: Linking knowledge sharing, absorptive capacity and innovation capability. High. Educ. Q. 2020, 74, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Medina, C.; López-Cabrales, Á.; Valle-Cabrera, R. Leveraging the innovative performance of human capital through HRM and social capital in Spanish firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M.J.; Peña, I.; Sánchez de Pablo, J.D. HRM practices for human and social capital development: Effects on innovation capabilities. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 928–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijauskiene, M.; Dumciuviene, D.; Vasauskaite, J. Redeveloping the national innovative capacity framework: European Union perspective. Economies 2021, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krücken, G. Multiple competitions in higher education: A conceptual approach. Innovation 2021, 23, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlommel, K.; Van den Boom-Muilenburg, S.N. How can we understand and stimulate evidence-informed educational change? A scoping review from a systems perspective. J. Educ. Change 2024, 25, 605–634. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D.; Hunter, S.T. Innovation in organizations: A multi-level perspective on creativity. In Multi-Level Issues in Strategy and Methods; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2005; pp. 9–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hedström, P.; Wennberg, K. Causal mechanisms in organization and innovation studies. Innovation 2017, 19, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, Q. Higher education in innovation ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorije, H.; Vanlommel, K. Unravelling Innovative Capacity of Teachers in the Context of Complex Educational Innovations: A Scoping Review. 2025; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, A.J.; Rodrigo-Moya, B.; Morcillo-Bellido, J. The effect of leadership in the development of innovation capacity: A learning organization perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Poortman, C. (Eds.) Networks for Learning: Effective Collaboration for Teacher, School and System Improvement; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]