Innovative Geoproduct Development for Sustainable Tourism: The Case of the Safi Geopark Project (Marrakesh–Safi Region, Morocco)

Abstract

1. Introduction

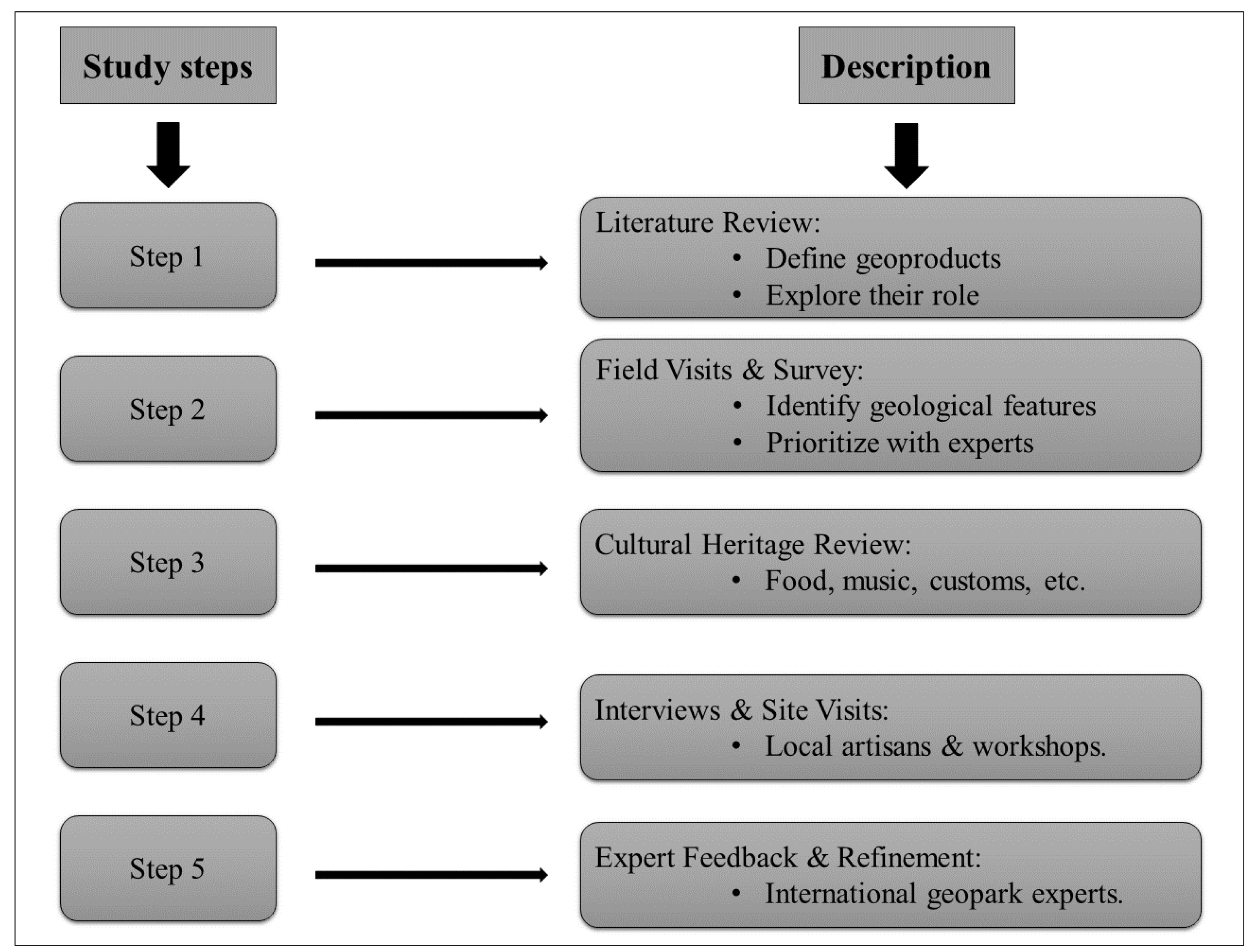

2. Materials and Methods

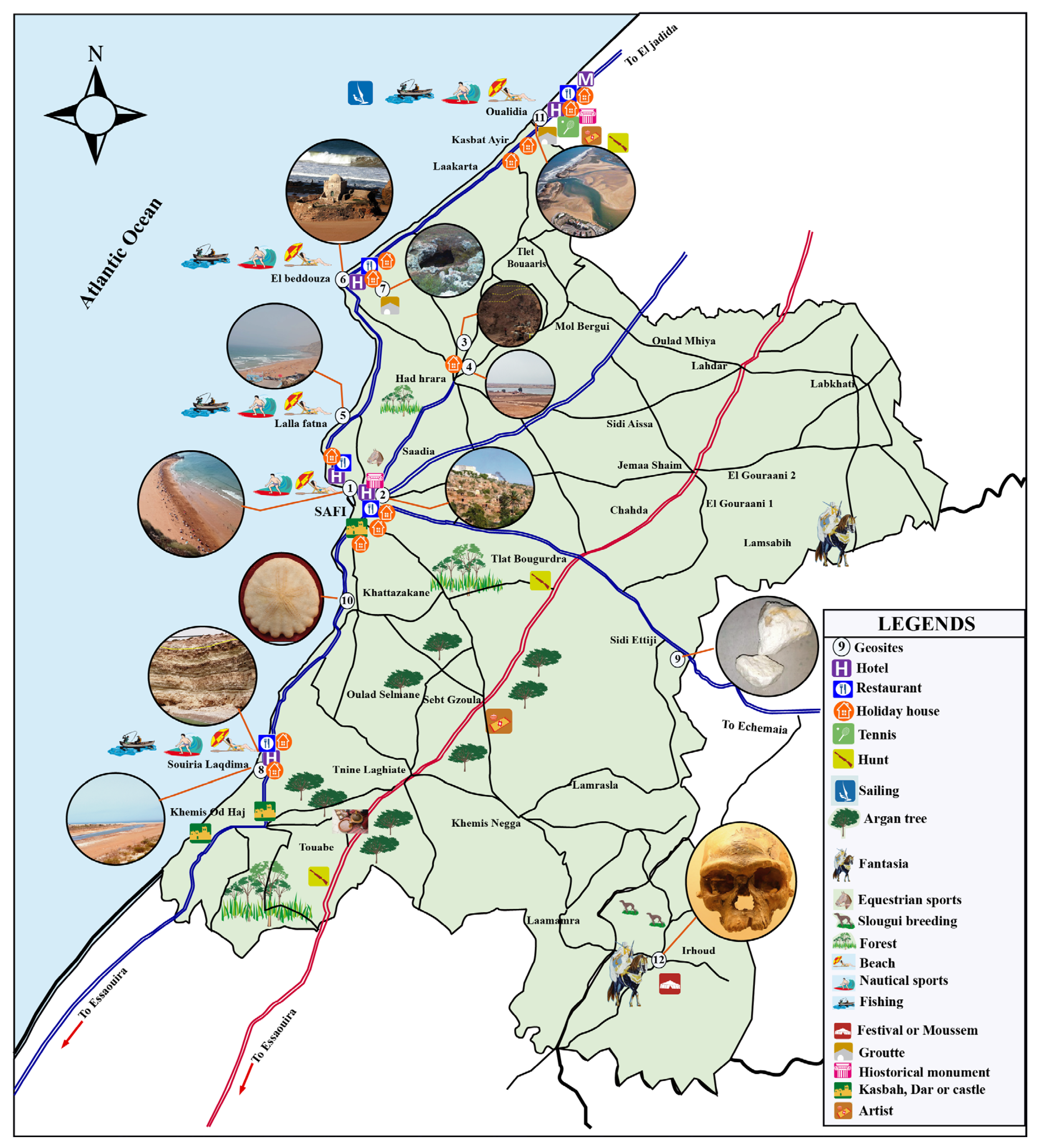

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

- (i)

- Literature Review

- (ii)

- Field Visits

- (iii)

- Expert Surveys

- (iv)

- Semi-Structured Interviews

- (v)

- Data Analysis and Concept Refinement

3. Results

3.1. Geoproducts: Concept and Objectives

3.1.1. Context

3.1.2. Definition and Types of Geoproducts

- Direct connection to the territory: Reflects the geographic, cultural, and/or natural identity of the region.

- Heritage inspiration: Is inspired by a specific element of the geological, biological, and/or cultural heritage of the territory.

- Territorial uniqueness: Is preferably unique to the territory, emphasizing its exclusive character.

- Local production: Ideally, it is produced on-site, using local materials as much as possible, from sustainable sources.

- Sustainability and ethics: Is created under environmentally friendly and ethically sound conditions.

- Crafts and merchandising;

- Food and cosmetics;

- Tourist infrastructure (restaurants and accommodation);

- Tourism-related services.

3.2. Why Are Geoproducts Important and How Can They Be Produced?

| Definitions | References |

|---|---|

| Geoproducts are defined as “the sustainable production of innovative handcrafted items with a geological connotation.” | [2] |

| Geoproducts: A New Direction for Crafts and Artisanal Trades | [22] |

| Geoproducts and geotourism represent new sources of income that can provide additional revenue for the local population and attract private investment. | [23] |

| Geoproducts are educational tools designed for teaching, training, and interdisciplinary research related to geoscientific disciplines, broader environmental issues, and sustainable development. | [25] |

| Geoproducts aim to integrate traditional products with new concepts and interpretations, while also raising awareness about geodiversity. They provide new experiences for geotourists and strive to foster the development of the local economy. | [24] |

| Geoproducts include geological features like geoheritage and geosites, along with human-made elements tied to cultural and architectural aspects of geotourism. They play a key role in preserving geological heritage while promoting sustainable tourism and local economic growth. | [27] |

| Geoproducts, as educational tools, are sustainable and environmentally friendly products that can integrate geoheritage (geological, geomorphological, and geographical) with cultural elements. As such, the production of geoproducts represents an innovative strategy to highlight geoheritage as a new tourist attraction. | [1,18] |

| Geoproducts are innovative, new, or reinvented traditional purchase items that are closely linked to or inspired by the geodiversity of a territory. | [41] |

| A geoproduct is a unique item for each geopark, directly connected to its territory and produced as much as possible using local materials and crafted locally. | [29] |

| A geoproduct can be defined as a commercial service or a manufactured item inspired by geodiversity. | [3] |

3.3. Conceptualization of Geoproducts for the Safi Geopark Project

3.3.1. Tangible Geoproducts—Sustainable Goods

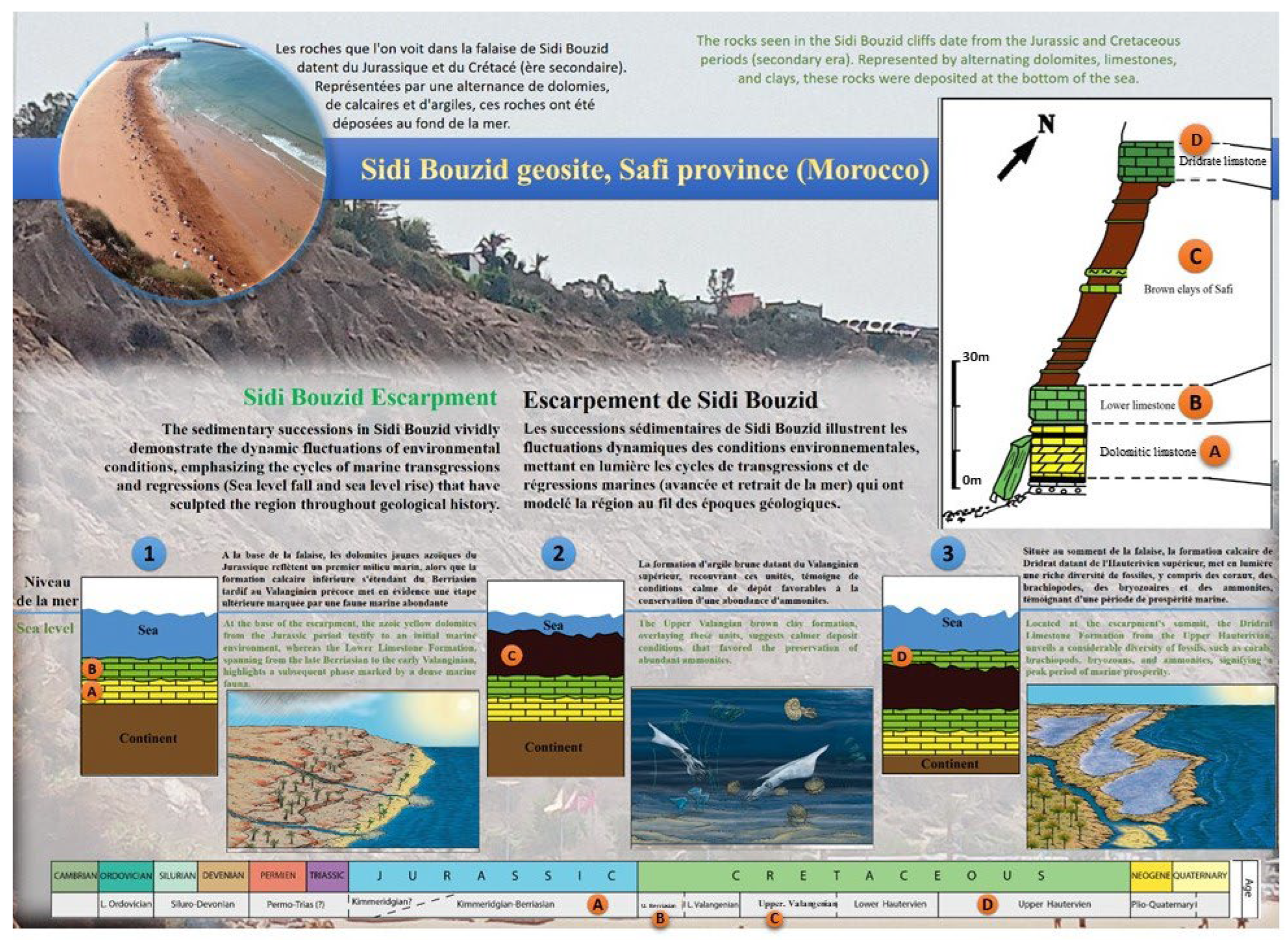

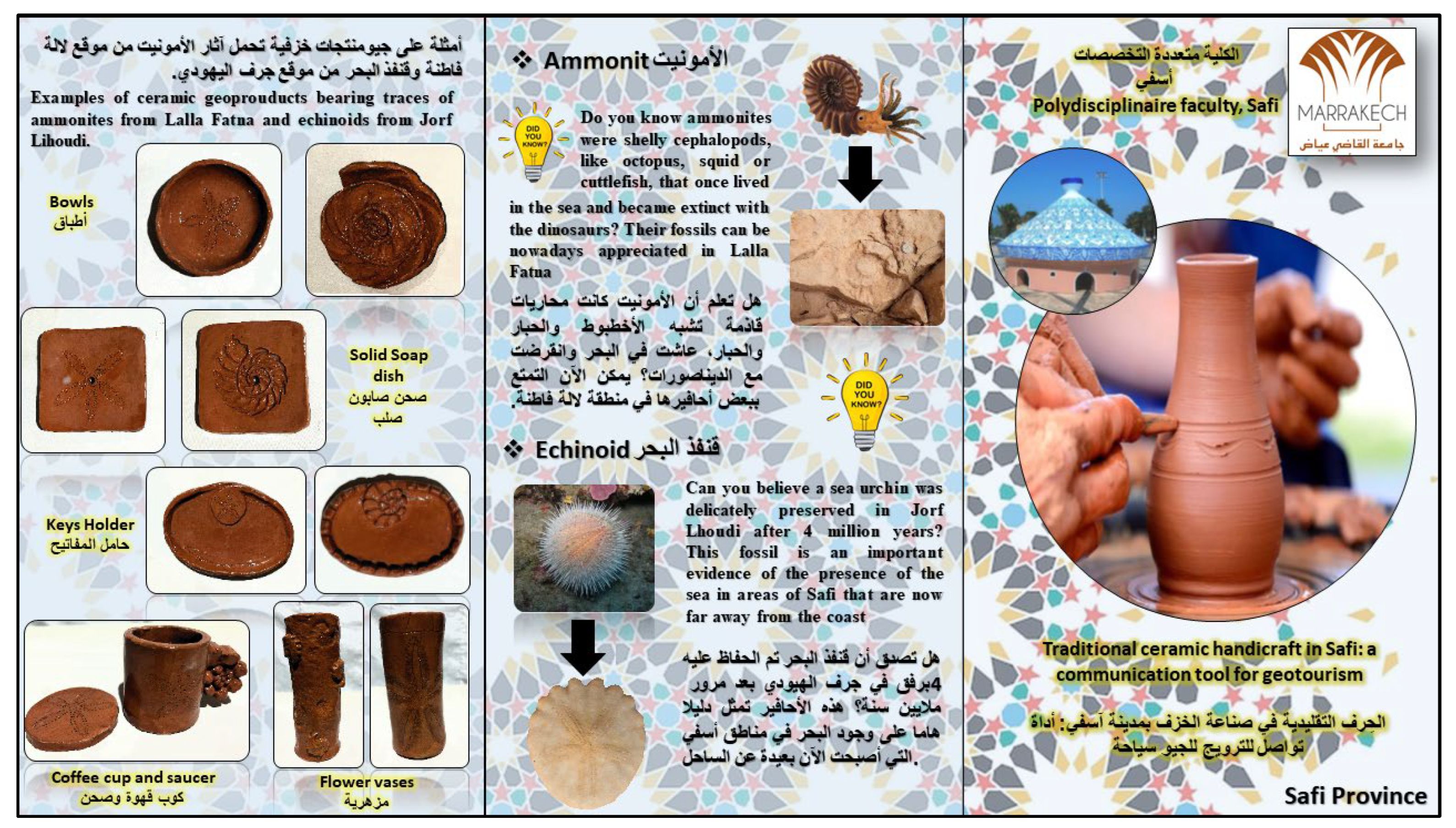

Utilitarian and Decorative Ceramic Objects

Clothing and Other Textiles (T-Shirts, Fabric Backpacks, Caps, etc.)

Functional Objects (Key Rings, Pen Holders, Pencil Holders, and Make-Up Brush Holders)

Educational Resources

- Geotourism Map

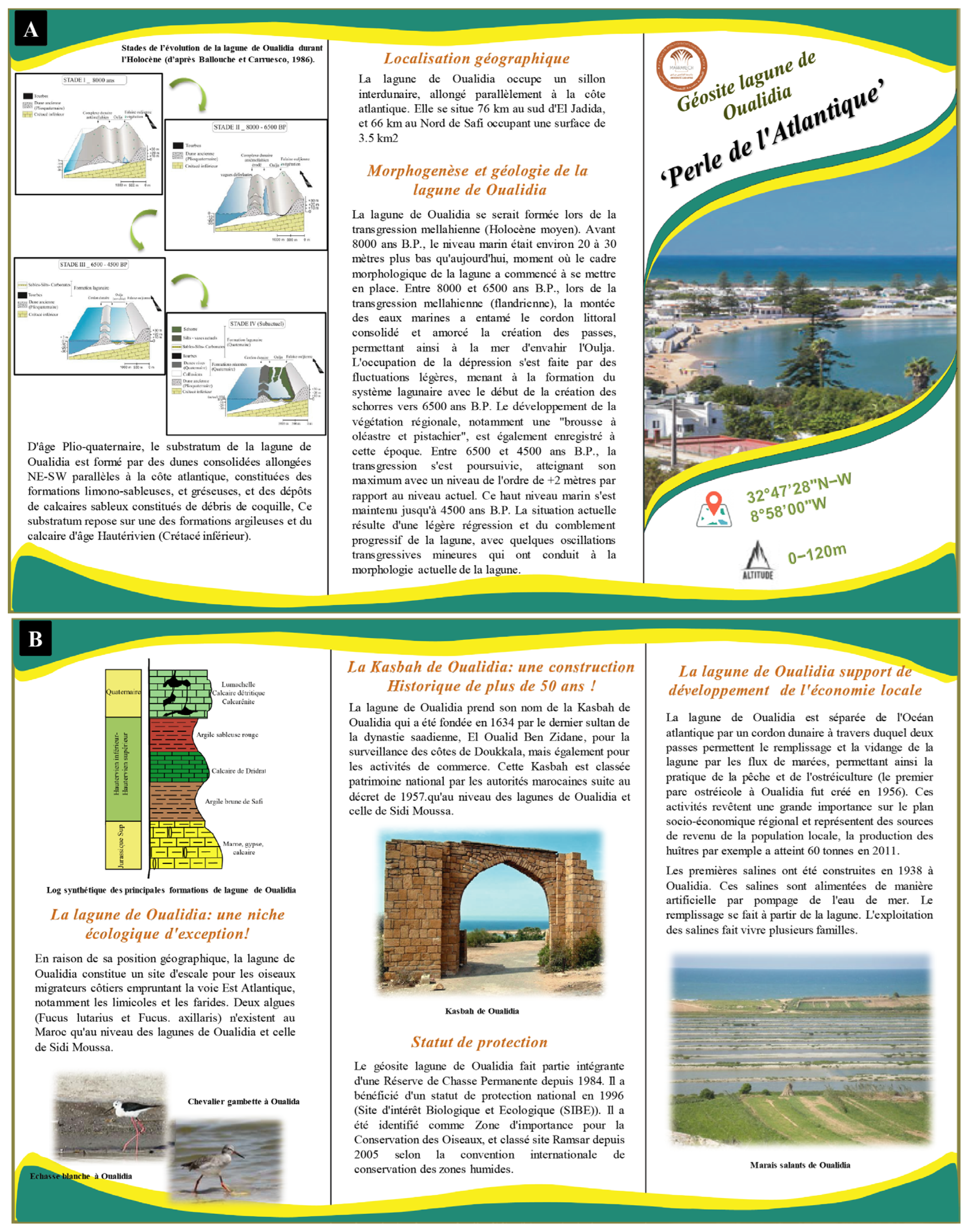

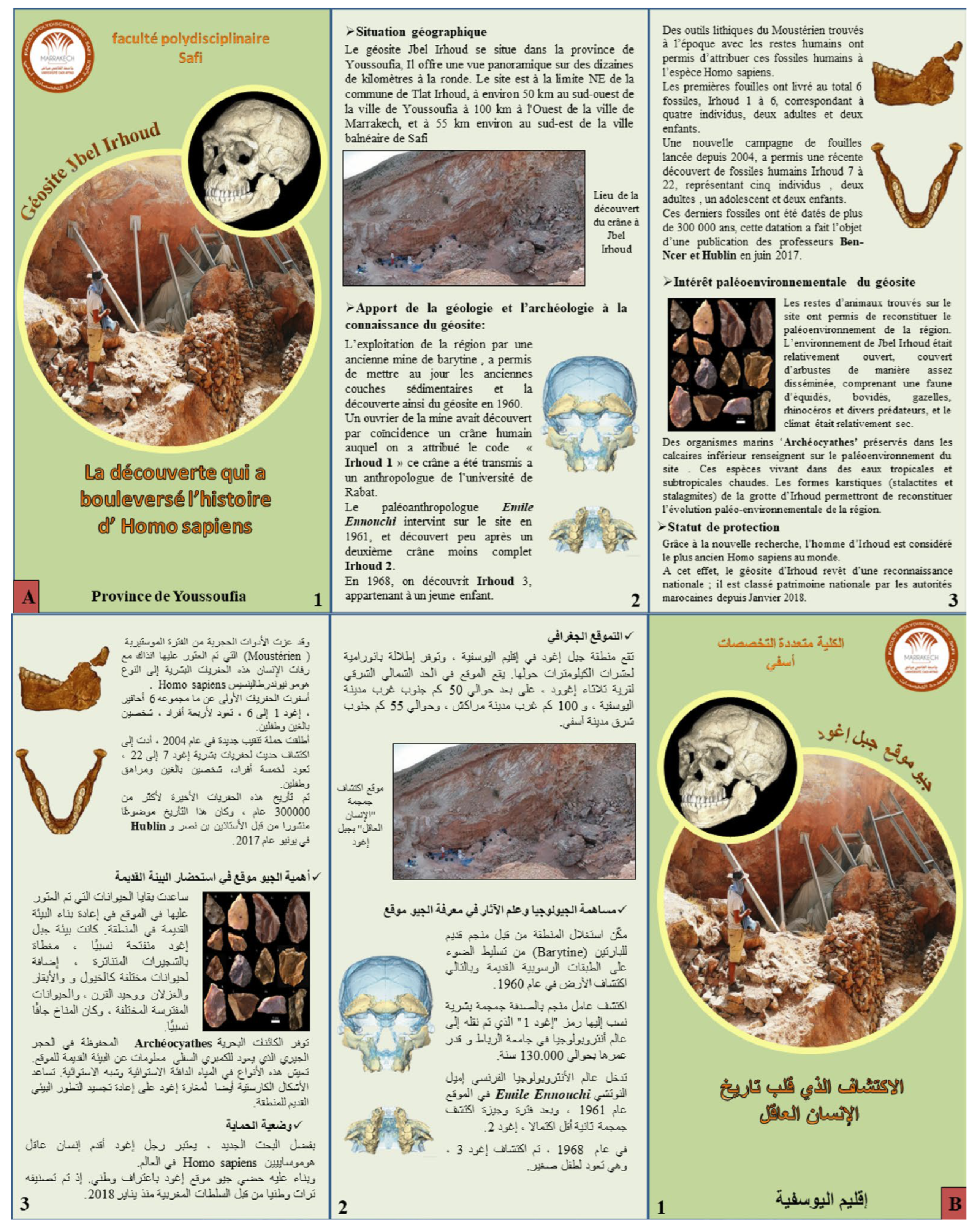

- Educational Brochures: Geoscience Outreach

- Interpretive Panels

3.3.2. Tangible Geoproducts—Non-Durable Goods

Edible Products (Cakes, Jellies, Pancakes, Chocolates)

- Kâak-Ammonite

- Kebbar Safi

- Oils

- “Kouita” Traditional Drink

- Health and Beauty Products

3.3.3. Intangible Geoproducts

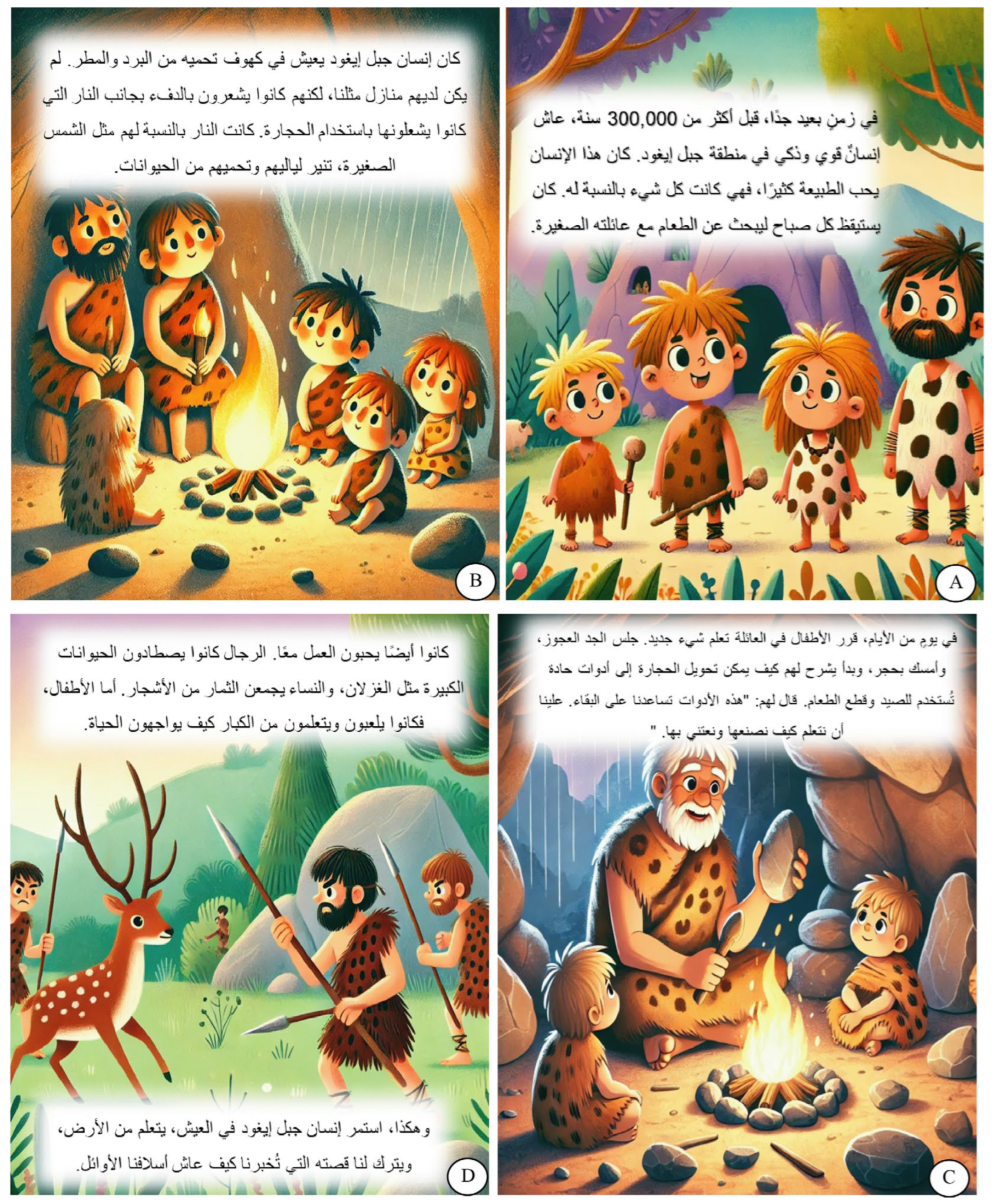

Augmented Reality (AR) Experience at Jbel Irhoud

Stories and Tales for Children About Jbel Irhoud

3.3.4. Services

Rental of Traditional Costumes in Safi

Painting and Pottery Workshops

3.4. Comparative SWOT Analysis of Geoproduct Concepts

3.4.1. Tangible Durable Goods (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats)

3.4.2. Tangible Non-Durable Goods (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats)

3.4.3. Intangible Geoproducts (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats)

3.4.4. Services (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Geotourism and geoparks as novel strategies for socio-economic development in rural areas. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO geoparks programme—A new initiative to promote a global network of geoparks safeguarding and developing selected areas having significant geological features. In Proceedings of the 156th Session of the Executive Board of UNESCO, Paris, France, 25 May–11 June 1999; Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001151/115177e.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2011).

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Geoproducts–Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology, and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enniouar, A.; Errami, E.; Lagnaoui, A.; Bouaala, O. Geoheritage of Doukkala-Abda region (Morocco): A tool for local socio-economical sustainable development. In From Geoheritage to Geoparks: Case Studies from Africa and Beyond; Errami, E., Brocx, M., Semeniuk, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; Elkaichi, A. An overview of scientific research on geoheritage in Morocco. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2024, 135, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; El Kabouri, J.; Naim, M.; Assouka, A.; Ait Ben Youssef, A.; El Bchari, F. Jbel Irhoud geosite (Youssoufia province, Marrakech-Safi region, Morocco), the cradle of humanity: Evaluation and valorisation of the geological heritage for geo-education and geotourism purposes. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; Orion, N. Proposed geo-educational activities at the Sidi Bouzid geosite, Safi Province, Marrakech-Safi region, Morocco. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2024, 12, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; Elkaichi, A. Current Trends and Future Directions for Geoheritage Assessment Methodology in Morocco. Geoconserv. Res. 2024, 7, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E. The geosites of Safi province (Marrakech-Safi region, Morocco): Inventory and assessment for geoconservation, geotourism, geoeducation, geoparks, and local sustainable development. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2025, 13, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Rodrigues, J. Traditional Ceramic Handicraft in Safi (Marrakesh-Safi Region, Morocco): A Communication Tool for Geotourism. Geoheritage 2025, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. Tourism: A Community Approach (RLE Tourism), 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. A Postcapitalist Politics; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Menegaki, A.N. Sustainable tourism production and consumption as constituents of sustainable tourism GDP: Lessons from a typical index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW). In Strategies in Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Clean Energy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Menegaki, A.N. How Do Tourism and Environmental Theories Intersect? Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K. Geotourism’s global growth. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.; Newsome, D. (Eds.) Geotourism; Elsevier, Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Geoparks and Geotourism: New Approaches to Sustainability for the 21st Century; Brown Walker Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, D.; Miśkiewicz, K. Construction of the geotourism product structure on the example of Poland. In Proceedings of the 14th SGEM2014 Geoconference on Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; Volume 2, pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Koutoulas, D. Understanding the Tourism Product. In Proceedings of the Interim Symposium of the Research Committee on International Tourism (RC 50) of the International Sociological Association (ISA), Mytilini, Greece, 14–16 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, U. Tourism product. In Tourism Marketing and Management Handbook; Witt, S.F., Moutinho, L., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 572–576. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, Z.; Milly, W. National geoparks initiated in China: Putting geoscience in the service of society. Episodes 2002, 25, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, W.; Patzak, M. Geoparks—Geological attractions: A tool for public education, recreation and sustainable economic development. Episodes 2004, 27, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C. (Eds.) Geotourist trails in Geopark Naturtejo. In New Challenges with Geotourism, Proceedings of the VIII European Geoparks Conference, Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal, 14–16 September 2009; European Geoparks Network: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, M.; Schaefer, K.; Buchel, G.; Patzak, M. Geoparks–A regional, European and global policy. In Geotourism; Newsome, D., Dowling, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 96–117. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Guidelines and criteria for national geoparks seeking UNESCO’s assistance to join the Global Geoparks Network (GGN). In UNESCO Global Geoparks Network Guidelines (2010); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; Available online: http://www.globalgeopark.org/UploadFiles/2012_9_6/GGN2010.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2010).

- Complova, M. The identification of geoproducts in the village of Jakubany as a basis for geotourism development. Acta Geoturistica 2010, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yuliawati, A.K.; Rofaida, R.; Gautama, B.P.; Hadian, M.S.D. Geoproduct Development as Part of Geotourism at Geopark Belitong. In Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Economics, Business, Entrepreneurship, and Finance (ICEBEF 2018), Lhokseumawe, Indonesia, 12–13 November 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, B.B. Geoproducts in Unesco Global Geoparks: A Study Applied to Platåbergens Aspiring Geopark (Sweden). Doctoral Dissertation, Universidade do Minh, Braga, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrikazemi, A.; Dakhteh, S.M.; Zobeiri, E.; Abdolmaleki, M.Q. Smart & Inclusive development in local communities, an enterprise in Qeshm Geopark, Iran. In Proceedings of the 11th European Geoparks Conference, Arouca, Portugal, 19–21 September 2012; Sá, A., Rocha, D., Paz, A., Correia, V., Eds.; European Geoparks Network: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, A.; Brandão, G.; Rocha, D.; Rodrigues, I. Geolnvolve Project: An example of community participation in Arouca Geopark (Portugal). In Proceedings of the International Congress of Geotourism—Arouca 2011, Arouca, Portugal, 9–13 November 2011; Rocha, D., Sá, A., Eds.; European Geoparks Network: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mawaddah, H.; Prasetyo, B.D.; Hussein, A.S. Branding Activities for Raja Ampat Geopark Development in the Pentahelix Model Perspective. J. Soc. 2024, 5, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, P.M.; Nasution, Z.; Rujiman; Ginting, N. The role of geological relationship and brand of geoproduct on regional development in samosir island of geopark caldera toba with mediating method. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2024, 52, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, Z.; Farsani, N.T.; Abdollahpour, M. The benefit of geo-branding in a rural geotourism destination: Isfahan, Iran. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2017, 19, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Çalışkan, C.; Karakuş, Y. Role of place image in support for tourism development: The mediating role of multi-dimensional impacts. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, S.; Skogen, C.; Thjømøe, P. The GEOfood brand: Local and international cooperation. Eur. Geoparks Netw. Mag. 2020, 17, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Çeşmeci, N.; Çulfacı, G.; Kılıçhan, R. Evaluating the gastronomy-related contents of the websites of UNESCO global geoparks in Europe. Tour. Recreat. 2024, 6, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.P. GEOfood Products, Tourism, and Ecocultural Sustainability for Vulnerable Territories: Projects and Strategies in Portuguese Geoparks. In Innovative Trends Shaping Food Marketing and Consumption; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 475–502. [Google Scholar]

- Neto de Carvalho, C.; Rodrigues, C. Development of Geoproducts as successful approaches to strengthen the identity. Eur. Geoparks Mag. 2017, 14, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Farsani, N.T.; Mortazavi, M.; Bahrami, A.; Kalantary, R.; Bizhaem, F.K. Traditional crafts: A tool for geo-education in geotourism. Geoheritage 2017, 9, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hublin, J.J.; Ben-Ncer, A.; Bailey, S.E.; Freidline, S.E.; Neubauer, S.; Skinner, M.M.; Bergmann, I.; Le Cabec, A.; Benazzi, S.; Harvati, K.; et al. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud (Morocco) and the Pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 2017, 546, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissig, G. Mapping geomorphosites: An analysis of geotourist maps. Geotourism/Geoturystyka 2008, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ballouche, A.; Carruesco, C. Evolution holocène d’un écosystème lagunaire: Lalagune Oualidia (Maroc atlantique). Rev. Géologie Dyn. Géographie Phys. 1986, 27, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Macadam, J. Geoheritage: Getting the message across. What message and to whom? In Geoheritage; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Sozzi, G.O. Caper bush: Botany and horticulture. In Horticultural Reviews; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 125–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lemhadri, A.; Achtak, H.; Lamraouhi, A.; Louidani, N.; Benali, T.; Dahbi, A.; Lyoussi, B. Diversity of medicinal plants used by the local communities of the coastal plateau of safi province (Morocco). Front. Biosci. 2023, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbir, M.; Es-Safi, N.E.; Amhoud, A.; Mbarki, M. Characterization of phenolic compounds in olive stones of three Moroccan varieties. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2015, 17, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, E.K. Evaluation de la Séquestration du CO2 et de l’Empreinte Carbone dans Quatre Systèmes de Culture de l’Olivier dans la Région Marrakech-Safi: Analyse du Cycle de Vie de l’Huile d’Olive. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nabil-Elkhatri/publication/367966477_Evaluation_de_la_sequestration_du_CO2_et_de_l’empreinte_carbone_dans_quatre_systemes_de_culture_de_l’olivier_Analyse_du_cycle_de_vie_de_l’huile_d’olive/links/63f4dcce0d98a97717a8809e/Evaluation-de-la-sequestration-du-CO2-et-de-lempreinte-carbone-dans-quatre-systemes-de-culture-de-lolivier-Analyse-du-cycle-de-vie-de-lhuile-dolive.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Zaroual, H.; El Hadrami, E.M.; Karoui, R. Preliminary study on the potential application of Fourier-transform mid-infrared for the evaluation of overall quality and authenticity of Moroccan virgin olive oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 2901–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Lozano, D.; Escámez, A.; Aguado, R.; Oulbi, S.; Hadria, R.; Vera, D. Techno-economic assessment of an off-grid biomass gasification CHP plant for an olive oil mill in the region of Marrakech-Safi, Morocco. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abbassi, A.; Khalid, N.; Zbakh, H.; Ahmad, A. Physicochemical characteristics, nutritional properties, and health benefits of argan oil: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1401–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsin, T.E.; Mounir, F.; El Aboudi, A. Conservation, valuation and sustainable development issues of the Argan Tree Biosphere Reserve in Morocco. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2020, 8, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgadi, S.; Ouhammou, A.; Taous, F.; Zine, H.; Papazoglou, E.G.; Elghali, T.; El Antari, A. Combination of stable isotopes and fatty acid composition for geographical origin discrimination of one argan oil vintage. Foods 2021, 10, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgadi, S.; Ouhammou, A.; Zine, H.; Maata, N.; Aitlhaj, A.; El Allali, H.; El Antari, A. Discrimination of geographical origin of unroasted kernels Argan oil (Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels) using tocopherols and Chemometrics. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 8884860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiri, C.; Tazi, B.; Maata, N.; Rahim, S.; Taki, H.; Bennamara, A.; Derouiche, A. Nutritional Assessment and Comparison of the Composition of Oil Extracted from Argan Nuts Collected from a Plantation and Two Natural Forest Stands of ARGAN Trees. Forests 2023, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouahabi, M.; Daoudi, L.; Fagel, N. Mineralogical and geotechnical characterization of clays from northern Morocco for their potential use in the ceramic industry. Clay Miner. 2014, 49, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouahabi, M.; El Idrissi, H.E.B.; Daoudi, L.; El Halim, M.; Fagel, N. Moroccan clay deposits: Physico-chemical properties in view of provenance studies on ancient ceramics. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 172, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghazdis, M.; El-Kaber, H.; Atman, B. Natural clays from Morocco: Potentials and applications. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2022, 17, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elataoui, K.; Harech, M.A.; Qobay, H.; Elbinna, N.; Aouad, H.; Waqif, M.; Saadi, L. Exploring the diversity of clays: Impacts of temperature on physicochemical changes, mechanical characteristics, and permeability, and their relevance to membrane applications. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2024, 63, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghazdis, M.; Hachem, E.K. Clay and clay minerals: A detailed review. Int. J. Recent Technol. Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaouy, M.E.; Belghazdis, M.; Hachem, E.K. Characterization of a Moroccan stevensite for future valorization in the cosmetic field. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3051, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage, Boston: Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. Boyle, E. Understanding brands as experiential spaces: Axiological implications for marketing strategists. J. Strateg. Mark. 2006, 14, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.; Von Der Dunk, A. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C. (Eds.) Geoproducts in Geopark Naturtejo. In New Challenges with Geotourism, Proceedings of the VIII European Geoparks Conference, Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal, 14–16 September 2009; European Geoparks Network: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, J.S. The GeoPark of Haute-Provence, France—Geology and palaeontology protected for sustainable development. Carnets Géologie 2009, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Geoproduct Concept | Geoproduct Examples for Safi |

|---|---|---|

| Tangible durable geoproducts: physical items made to last, reflecting the region’s heritage, craftsmanship, or natural resources. These products are produced with quality materials and skilled techniques, offering long-term use while embodying cultural and geological identity. | Utilitarian and decorative ceramic objects | Fossil-inspired ceramic items: bowls, key rings, flower vases, soap dishes, and coffee cups and saucers |

| Clothing and other textiles (T-shirts, fabric backpacks, caps, etc.) | Embroidered scarves, cushions, bags, and clothing with fossil motifs, including ammonite and Jbel Irhoud skull designs | |

| Functional objects (key rings, pen holders, pencil holders, and make-up brush holders) | Plaster-based functional objects inspired by the Irhoud skull | |

| Educational resources | Geotourism maps, educational brochures for Jbel Irhoud and Oualidia Lagoon, interpretive panels at geosites | |

| Tangible non-durable geoproducts: consumable or perishable physical products that showcase local ingredients, traditions, or artisanal practices. Often food, beverages, or wellness items, they highlight the region’s flavors, natural resources, and cultural know-how. | Edible products (cakes, jellies, pancakes, and chocolates) | Kâak Ammonite (a traditional biscuit ammonite shaped), Kebbar Safi (pickled capers), olive oil, argan oil, Kouita (traditional drink) |

| Health and beauty products | Natural masks and soaps made from Safi’s clays | |

| Intangible geoproducts: non-physical experiences that offer immersive cultural, historical, or educational engagement. These are often delivered through digital or creative formats, such as storytelling, or performances, and serve to convey the region’s identity, traditions, and geological significance. | Augmented reality (AR) experience | AR mobile app offering 3D reconstructions of human fossils, prehistoric tools, and rock formations |

| Stories and tales for children | Illustrated stories and tales about prehistoric life, with interactive workshops where children can make small clay objects | |

| Services: visitor experiences that facilitate direct interaction with the region’s culture, heritage, or landscapes. These may include hands-on workshops, cultural immersion activities, guided tours, or traditional costume rentals, offering meaningful ways to engage with local traditions, craftsmanship, and the geological identity of the area. | Rental of traditional costumes | Renting traditional Safi garments such as djellabas and caftans for photoshoots and cultural immersion experiences |

| Painting and pottery workshops | Workshops for pottery and painting, where visitors create their own pieces inspired by traditional craftsmanship and geological motifs |

| Category | Geoproduct Concept | Geoproduct Examples for Safi | Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Durable Goods | Ceramic Objects | Fossil-inspired ceramics (ammonites, echinoids) | Use of local high-quality clay; strong geological identity | Requires skilled artisans; geological motifs may sometimes seem unusual to some people. | Unique souvenirs; supports local crafts and economy | Production costs; artisan shortages |

| Clothing and Textiles | Embroidered scarves, fabric backpacks, caps with fossil and Jbel Irhoud skull motifs | Deep cultural roots; artistic and educational value | Possibly higher production costs; need for fresh designs | Cultural storytelling; tourist souvenirs; strong branding | Market competition; changing consumer trends | |

| Functional Objects | Key rings, pen holders, pencil holders, make-up brush holders shaped like Jbel Irhoud skull | Use of abundant local gypsum; combines geology and culture | Requires design innovation; small market size | Unique gifts; promotes geological heritage | Market niche size; production scalability | |

| Educational Resources | Geotourism maps, brochures, interpretive panels | Enhances visitor education and engagement; supports geotourism | Requires investment for development and updates | Partnerships with schools and tourism agencies | Limited visitor engagement without promotion | |

| Tangible Non-Durable Goods | Edible Products | Kâak Ammonite biscuits, Kebbar capers, olive and argan oils | Strong local culinary heritage; unique geo-linked ingredients | Shelf-life limitations; food safety regulations | Promotion of festivals and markets; culinary tourism growth | Regulatory issues; seasonal variations |

| Health and Beauty Products | Clay-based masks, soaps | Rich mineralogical resources; growing eco-friendly market | Certification and marketing needed | Eco-friendly niche market; local and export potential | Competition; regulatory hurdles | |

| Intangible Geoproducts | Augmented Reality (AR) Experience | Mobile app with 3D reconstructions at Jbel Irhoud site | Innovative, immersive; appeals to diverse audiences | High development and maintenance costs | Educational outreach; broad accessibility | Technical barriers; limited digital access |

| Stories and Tales for Children | Illustrated prehistoric stories and workshops at Jbel Irhoud site | Engaging for children; preserves cultural memory | Requires creative content development and funding | Educational programs; strengthens local heritage | Limited reach without active promotion | |

| Services | Traditional Costume Rental | Djellaba and caftan rental with photography sessions | Unique cultural experience; low material cost | Seasonal demand; costume maintenance | Cultural tourism; event-based marketing | Preservation challenges; fluctuating tourist numbers |

| Painting and Pottery Workshops | Hands-on workshops for visitors to learn pottery and painting | Interactive and immersive; skills transfer | Need skilled facilitators; limited group sizes | Community engagement; unique visitor experiences | Material costs; scalability challenges |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Rodrigues, J. Innovative Geoproduct Development for Sustainable Tourism: The Case of the Safi Geopark Project (Marrakesh–Safi Region, Morocco). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146478

El Hamidy M, Errami E, Neto de Carvalho C, Rodrigues J. Innovative Geoproduct Development for Sustainable Tourism: The Case of the Safi Geopark Project (Marrakesh–Safi Region, Morocco). Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146478

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Hamidy, Mustapha, Ezzoura Errami, Carlos Neto de Carvalho, and Joana Rodrigues. 2025. "Innovative Geoproduct Development for Sustainable Tourism: The Case of the Safi Geopark Project (Marrakesh–Safi Region, Morocco)" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146478

APA StyleEl Hamidy, M., Errami, E., Neto de Carvalho, C., & Rodrigues, J. (2025). Innovative Geoproduct Development for Sustainable Tourism: The Case of the Safi Geopark Project (Marrakesh–Safi Region, Morocco). Sustainability, 17(14), 6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146478