Countering Climate Fear with Mindfulness: A Framework for Sustainable Behavioral Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Limitations of Fear-Based Climate Communication

2.1. Acute vs. Chronic Fear Responses

2.2. Cultural and Socio-Economic Variability in Fear-Processing

2.3. Trauma-Informed Critique of Fear-Based Campaigns

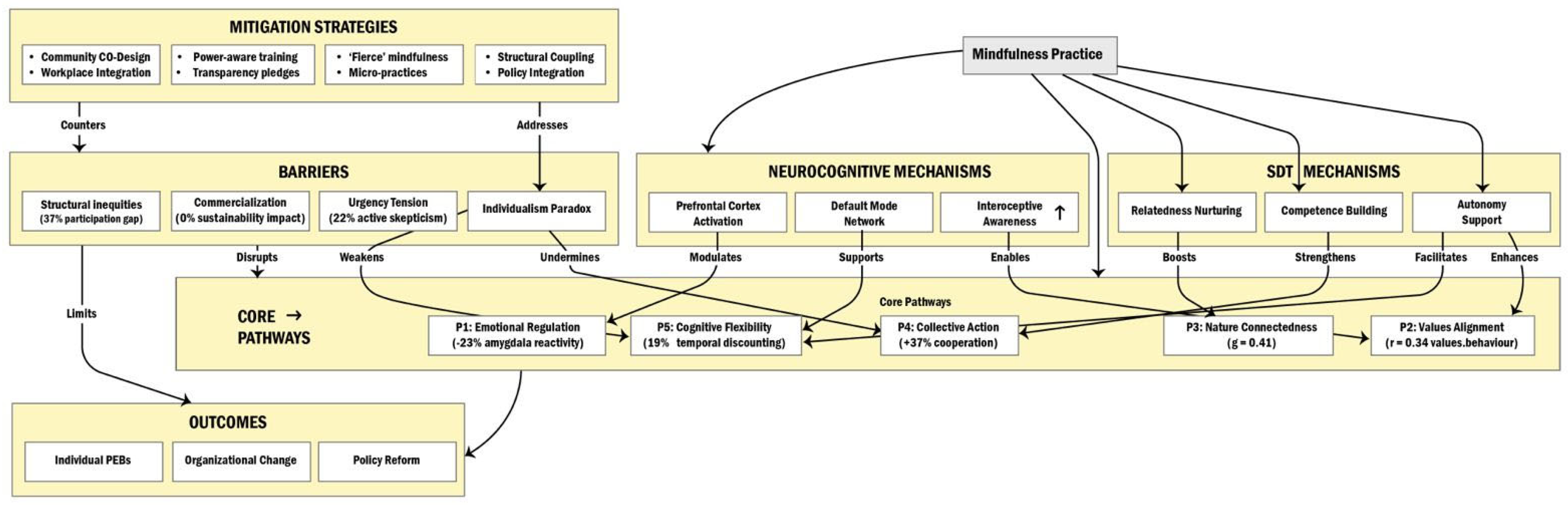

2.4. Mindfulness for Pro-Environmental Action: A Conceptual Framework

3. Theoretical Foundations

3.1. Neurocognitive (NCT) Mechanisms: Rewiring the Brain for Resilience

3.1.1. Enhanced Interoceptive Awareness: The Insular Cortex as a Hub

3.1.2. Increased Prefrontal Cortex Activation: Top-Down Regulation and Cognitive Control

3.1.3. Suppression of the Default Mode Network: Reducing Self-Referential Narrative

3.1.4. Integration and Neuroplastic Rewiring

3.2. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

3.3. Social Diffusion Theory and Propagation of Mindfulness Practices

4. Pro-Environmental Behavior Pathways

4.1. Pathway 1: Emotional Regulation and Resilience

4.2. Pathway 2: Cognitive Flexibility and Ethical Decision-Making

- Reduced Temporal Discounting: Mindfulness practitioners exhibit significantly lower temporal discounting rates (β = −0.22, p < 0.05 [89]), meaning they place greater relative value on future rewards and consequences compared to immediate gratification. This shift is linked to increased activation in brain regions associated with future-oriented thinking (e.g., prefrontal cortex) and reduced activity in regions linked to impulsive reward processing (e.g., ventral striatum) during intertemporal choice tasks [89]. This makes practitioners more likely to prioritize long-term environmental benefits over short-term conveniences or costs.

- Enhanced Recognition of Ecological Interdependencies: Mindfulness cultivates a heightened awareness of interconnectedness, leading to significantly improved recognition of complex ecological relationships (η2 = 0.11; [1]). This involves moving beyond simplistic, linear thinking to appreciate systemic feedback loops, unintended consequences, and the embeddedness of human actions within natural systems [90,91]. This systemic understanding fosters a stronger sense of responsibility towards the broader web of life.

- Decreased Vulnerability to Greenwashing: Practitioners demonstrate greater resistance to deceptive environmental marketing. Mindfulness enhances critical evaluation skills and reduces susceptibility to superficial cues (e.g., nature imagery, vague claims like “eco-friendly”) by promoting present-moment attention to actual substance and reducing reliance on cognitive heuristics [92]. However, this effect is context-dependent, with weaker impacts observed specifically for environmental greenwashing claims compared to corporate social responsibility greenwashing, potentially due to the higher complexity and lower consumer familiarity with detailed environmental credentials [92,93].

- This cultivation of cognitive flexibility is fundamental for ethical decision-making in the sustainability domain. It allows practitioners to overcome deeply ingrained system justification biases—the tendency to defend and rationalize the status quo even when it is harmful—by enabling critical examination of existing socio-economic structures and consumption norms [94,95]. Furthermore, it directly mitigates future discounting tendencies [44], fostering a stronger sense of future self-continuity [86]. This enhanced connection with one’s future self makes the long-term consequences of environmental degradation feel more personally relevant and urgent, motivating present actions to safeguard future well-being [86]. This cognitive shift cultivates transformational individuals capable of stepping outside societal norms that often impede climate action, envisioning alternative futures, and challenging unsustainable practices [12,96].

- Additionally, mindfulness supports intrinsic motivation (Pathway 4), reduces activist burnout by buffering chronic stress and fostering resilience [97,98], and shows promise in helping to bridge ideological divides that obstruct environmental progress. This occurs by reducing cognitive rigidity and fostering perspective-taking and empathic concern, even towards those holding differing views [99].

4.3. Pathway 3: Connectedness to Nature

4.4. Pathway 4: Intrinsic Motivation and Values Alignment

4.5. Pathway 5: Self to Social Transformation: Collective Action

5. Barriers to Scaling and Mitigation Strategies

5.1. Structural Inequities

5.2. Co-Optation and Commercialization Risks

5.3. Urgency-Compatibility Tension

5.4. The Individualism Paradox

6. Discussion: Scaling and Systemic Integration of Mindfulness for Sustainability

6.1. Policy Integration: Mainstreaming Mindfulness in Governance

6.2. Organizational-Level or Workplace Systems: Structural Embedding

7. A Social Diffusion Framework for Scaling Mindfulness in Sustainability Policy and Organizations

7.1. Institutionalization Through Policy and Structural Change

7.2. Organizational Adoption Through Networked Leadership

7.3. Cultural Adaptation and Community-Based Diffusion

7.4. Economic and Technological Acceleration

7.5. Implementation Phasing and Networked Governance

8. Implications for Future Research

8.1. Mindfulness-Mechanisms-Pathways

8.2. Pathway—Outcomes

8.3. Barrier Interactions

8.4. Strategy Efficacy

8.5. Cross-Mechanism Effects

8.6. Real-World Impact

9. Research Design Framework

10. Method

10.1. Sampling Plan

10.2. Experimental Conditions

10.3. Measures and Type of Data

10.4. Data Analysis

10.5. Controls and Validity

10.6. Ethical Considerations

11. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Bristow, J. At the intersection of mind and climate change: Integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice. Clim. Change 2022, 173, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeDoux, J.E. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000, 23, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, G.J.; Ruiter, R.A.; Kok, G. Threatening communication: A critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7 (Suppl. S1), S8–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Stanszus, L.; Geiger, S.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Mind the gap: The role of mindfulness in adapting to increasing risk and climate change. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, B.K.; Lazar, S.W.; Gard, T.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Vago, D.R.; Ott, U. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action from a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. A J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Kasser, T. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 74, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, E.; Manning, C.; Scott, B.; Koger, S. Beyond the roots of human inaction: Fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 2017, 356, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kral, T.R.A.; Schuyler, B.S.; Mumford, J.A.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage 2018, 181, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purser, R.E. McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality; Repeater Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.L.; Minor, K.; Hayes, K.; Williams, K.G.; Howard, C. Ecological grief and anxiety: The start of a healthy response to climate change? Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, E261–E263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet. Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress in Health and Disease; Butterworths: Boston, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Helplessness: On Depression, Development, and Death; H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cunsolo, A.; Neville, R.E. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 4275–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C. We need to (find a way to) talk about Eco-anxiety. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2020, 34, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutar, C.; Wand, A.P.F. Understanding the Spectrum of Anxiety Responses to Climate Change: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. (Ed.) Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, K.-P.; Milfont, T.L. Towards cross-cultural environmental psychology: A state-of-the-art review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.W.; Harper, S.L.; Ford, J.D. Climate change and mental health: An exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Clim. Change 2013, 121, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moheseni-Cheraghlou, A.; Evans, H.; Climate Change Prioritization in Low-Income and Developing Countries. Atlantic Council 2024. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/climate-change-prioritization-in-low-income-and-developing-countries/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, I.L.; Pearlman, L.A. Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. J. Stress. 1990, 3, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. Fear Won’t Do It: Promoting Positive Engagement with Climate Change Through Visual and Iconic Representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Mental health risk and resilience among climate scientists. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. The MIT Press. JSTOR. 2011. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhfvf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Tang, Y.; Geng, L.; Schultz, P.W.; Zhou, K.; Xiang, P. The effects of mindful learning on pro-environmental behavior: A self-expansion perspective. Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 51, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brossmann, J.; Hendersson, H.; Kristjansdottir, R.; McDonald, C.; Scarampi, P. Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L.; Joy, S. Rousing Collective Compassion at Societal Level: Lessons from Newspaper Reports on Asian Tsunami in India. IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Schäpke, N.; Fraude, C.; Stasiak, D.; Bruhn, T.; Lawrence, M.; Mundaca, L. Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7432-5823-4. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel—Now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farb, N.A.; Segal, Z.V.; Mayberg, H.; Bean, J.; McKeon, D.; Fatima, Z.; Anderson, A.K. Attending to the present: Mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2007, 2, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.C.; Nijeboer, S.; Dixon, M.L.; Floman, J.L.; Ellamil, M.; Rumak, S.P.; Sedlmeier, P.; Christoff, K. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 43, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farb, N.; Daubenmier, J.; Price, C.J.; Gard, T.; Kerr, C.; Dunn, B.D.; Klein, A.C.; Paulus, M.P.; Mehling, W.E. Interoception, contemplative practice, and health. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, L.; Thom, N.J.; Shukla, A.; Davenport, P.W.; Simmons, A.N.; Stanley, E.A.; Paulus, M.P.; Johnson, D.C. Mindfulness-based training attenuates insula response to an aversive interoceptive challenge. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Hölzel, B.K.; Posner, M.I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, P.R.; Gross, J.J. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion 2010, 10, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Slagter, H.A.; Dunne, J.D.; Davidson, R.J. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichle, M.E.; MacLeod, A.M.; Snyder, A.Z.; Powers, W.J.; Gusnard, D.A.; Shulman, G.L. A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.P.; Furman, D.J.; Chang, C.; Thomason, M.E.; Dennis, E.; Gotlib, I.H. Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.A.; Worhunsky, P.D.; Gray, J.R.; Tang, Y.Y.; Weber, J.; Kober, H. Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20254–20259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.C.; Dixon, M.L.; Nijeboer, S.; Girn, M.; Floman, J.L.; Lifshitz, M.; Ellamil, M.; Sedlmeier, P.; Christoff, K. Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 65, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasino, B.; Fregona, S.; Skrap, M.; Fabbro, F. Meditation-related activations are modulated by the practices needed to obtain it and by the expertise: An ALE meta-analysis study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 6, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josipovic, Z. Neural correlates of nondual awareness in meditation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1307, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, S.W.; Kerr, C.E.; Wasserman, R.H.; Gray, J.R.; Greve, D.N.; Treadway, M.T.; Fischl, B. Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1893–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, D.; Hamblin, M.R.; Lakshmanan, S. Meditation and Yoga can Modulate Brain Mechanisms that affect Behavior and Anxiety-A Modern Scientific Perspective. Anc. Sci. 2015, 2, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkranz, M.A.; Davidson, R.J.; Maccoon, D.G.; Sheridan, J.F.; Kalin, N.H.; Lutz, A. A comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and an active control in modulation of neurogenic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 27, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, F.; Johnson, S.K.; Diamond, B.J.; David, Z.; Goolkasian, P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious. Cogn. 2010, 19, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vago, D.R.; Silbersweig, D.A. Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Huta, V.; Deci, E.L. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Ryan, R.M. Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baard, P.P.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Cultural variation in the self-concept. In The Self: Interdisciplinary Approaches; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 18–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Verstuyf, J. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.; Huang, C.L.; Lin, Y.C. Mindfulness, Basic Psychological Needs Fulfillment, and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.N.; Bradshaw, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Basarkod, G.; Ciarorochi, J.; Duineveld, J.J.; Guo, J.; Sahdra, B.K. Mindfulness and its association with varied types of motivation: A systematic review and meta-analysis using Self-Determination Theory. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 46, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.P.; Ryan, R.M.; Niemiec, C.P.; Legate, N.; Williams, G.C. Mindfulness, Work Climate, and Psychological Need Satisfaction in Employee Well-being. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusainy, C.; Lawrence, C. Brief mindfulness induction could reduce aggression after depletion. Conscious. Cogn. 2015, 33, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, N.; Gaspar Swim, J.K.; Fraser, J. Untangling the components of hope: Increasing pathways (not agency) explains the success of an intervention that increases educators’ climate change discussions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karremans, J.C.; Schellekens, M.P.; Kappen, G. Bridging the Sciences of Mindfulness and Romantic Relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. An. Off. J. Soc. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Inc. 2017, 21, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Passmore, H.-A.; Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Dopko, R.L. Flourishing in nature: A review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its applications as a positive psychology intervention. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 83, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T.W. Network Interventions. Science 2012, 337, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1, pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, B.E.; Coffey, K.A.; Cohn, M.A.; Catalino, L.I.; Vacharkulksemsuk, T.; Algoe, S.B.; Fredrickson, B.L. How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G.; Coutifaris, C.G.V.; Pillemer, J. Emotional contagion in organizational life. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C.; Constantinides, E. Emotional contagion: A brief overview and future directions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Hirvonen, J.; Parkkola, R.; Hietanen, J.K. Is emotional contagion special? An fMRI study on neural systems for affective and cognitive empathy. NeuroImage 2008, 43, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.; Liu, J. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Employee Workplace Green Behavior: Moderated Mediation Model of Green Role Modeling and Employees’ Perceived CSR. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. The social psychology of work engagement: State of the field. Career Dev. Int. 2022, 27, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, A.; Gross, J.J. Digital emotion contagion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C.K.; Siegel, R.D.; Fulton, P.R. (Eds.) Mindfulness and Psychotherapy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken, W.; Watkins, E.; Holden, E.; White, K.; Taylor, R.S.; Byford, S.; Evans, A.; Radford, S.; Teasdale, J.D.; Dalgleish, T. How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brink, E. Mindsets for sustainability: Exploring the link between mindfulness and sustainable climate adaptation. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 153, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimecki, O.M.; Leiberg, S.; Ricard, M.; Singer, T. Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershfield, H.E. Future self-continuity: How conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1235, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.; Reiner, K.; Meiran, N. Mind the trap: Mindfulness practice reduces cognitive rigidity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Malinowski, P. Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Conscious. Cogn. 2009, 18, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Otten, S.; Schötz, E.; Sarikaya, A.; Lehnen, H.; Jo, H.-G.; Kohls, N.; Schmidt, S.; Meissner, K. Subjective expansion of extended time-spans in experienced meditators. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Jovic, E.; Brinkerhoff, M.B. Personal and Planetary Well-being: Mindfulness Meditation, Pro-environmental Behavior and Personal Quality of Life in a Survey from the Social Justice and Ecological Sustainability Movement. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 93, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylowska, L.; Ackerman, D.L.; Yang, M.H.; Futrell, J.L.; Horton, N.L.; Hale, T.S.; Pataki, C.; Smalley, S.L. Mindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD: A feasibility study. J. Atten. Disord. 2008, 11, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Johnson, G. Beyond greenwashing: Addressing ‘the great illusion’ of green advertising. Responsible Organ. Rev. 2021, 16, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Schultz, M.D. From Greenwashing to Machinewashing: A Model and Future Directions Derived from Reasoning by Analogy. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 1063–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Banaji, M.R.; Nosek, B.A. A Decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated Evidence of Conscious and Unconscious Bolstering of the Status Quo. Political Psychol. 2004, 25, 881–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueke, A.; Gibson, B. Mindfulness Meditation Reduces Implicit Age and Race Bias: The Role of Reduced Automaticity of Responding. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2014, 6, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, J.; Friedrich, C.; Dawson, A.F.; Modrego-Alarcón, M.; Gebbing, P.; Delgado-Suárez, I.; Gupta, R.; Dean, L.; Dalgleish, T.; White, I.R.; et al. Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L. Social Mindfulness Adoption and Functional Use in a Classroom Context: A Qualitative Developmental Model. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2023, 88, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Jason, G.; de Mazancourt, C.; Parmesan, C.; Singer, M.C.; Loreau, M. Human-nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: A global meta-analysis. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M. Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: A meta-analytic investigation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 127, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.E.; Pelletier, L.G. Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2019, 60, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.A.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship. Int. J. Wellbeing 2021, 11, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, B.B.; Feng, X. A lower connection to nature is related to lower mental health benefits from nature contact. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Grandpierre, Z. Mindfulness in nature enhances connectedness and mood. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, T.; Kjønstad, B.G.; Barstad, A. Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Stanszus, L.S.; Frank, P.; Geiger, S.M. Healthy eating and sustainable nutrition through mindfulness? Mixed method results of a controlled intervention study. Appetite 2019, 141, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Przybylski, A.K.; Ryan, R.M. Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Otto, S.; Schrader, U. Mindfully Green and Healthy: An Indirect Path from Mindfulness to Ecological Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, N.; Pickett, S.M. Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: Implications for proenvironmental behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherell, J. Simmer-Brown Spiritual bypassing in the contemporary mindfulness movement. ICEA J. 2017, 1, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Trammel, R.C. Tracing the roots of mindfulness: Transcendence in Buddhism and Christianity. J. Relig. Spiritual. Soc. Work Soc. Thought 2017, 36, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wicks, J.C.; Scharmer, O.; Pavlovich, K. Exploring transcendental leadership: A conversation. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2015, 12, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L.C.; Goltz, S.M. Beyond Social Exchange Theory: An Integrative Look at Transcendent Mental Models for Engagement. Integral Theory 2014, 10, 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, P.; Desbordes, G.; Miller, W.B.; DeSteno, D. Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2125–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Sassenrath, C.; Schindler, S. Feelings for the Suffering of Others and the Environment: Compassion Fosters Proenvironmental Tendencies. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Van Lange, D.A.W.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Social mindfulness: Skill and will to navigate the social world. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 105, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oyler, D.L.; Price-Blackshear, M.A.; Pratscher, S.D.; Bettencourt, B.A. Mindfulness and intergroup bias: A systematic review. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2021, 25, 1107–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, C.C.; Fehr, E. The neurobiology of rewards and values in social decision making. Nat. Reviews Neurosci. 2014, 15, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; Narayanan, J.; Ho, Z.W. Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengieza, M.L.; Swim, J.K.; Hunt, C.A. Effects of post-trip eudaimonic reflections on affect, self-transcendence and philanthropy. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 41, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Lee, K.; Shin, S. Access to Urban Green Space in Cities of the Global South: A Systematic Literature Review. Urban. Sci. 2018, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D.N. What is Critical Environmental Justice; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, J.; Bergen-Cico, D. Exploring the adaptation of mindfulness interventions to address stress and health in Native American communities. In Beyond White Mindfulness: Critical Perspectives on Racism, Well-Being and Liberation; Fleming, C.M., Womack, V.Y., Proulx, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.H.; German, D.; Ricker, A. Feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a culturally informed intervention to decrease stress and promote well-being in reservation-based Native American Head Start teachers. BMC Public Health 2013, 23, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Wallace, J.; Land, C.; Patey, J. Re-organising wellbeing: Contexts, critiques and contestations of dominant wellbeing narratives. Organization 2023, 30, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. Mindfulness and moral outrage: Friends or foes? Philos. East. West 2021, 71, 825–841. [Google Scholar]

- Crippen, M. Africapitalism, Ubuntu, and Sustainability. Environ. Ethics 2021, 43, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, O.S. Ubuntu and the Problem of Belonging Ethics. Policy Environ. 2024, 27, 350–370. [Google Scholar]

- Poonamallee, L. Advaita (Non-dualism) as Metatheory: A Constellation of Ontology, Epistemology, and Praxis. Integral Rev. 2010, 6, 190–200. Available online: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1391&context=business-fp (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Hytman, L.; Amestoy, M.E.; Ueberholz, R.Y. Cultural Adaptations of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Psychosocial Well-Being in Ethno-Racial Minority Populations: A Systematic Narrative Review. Mindfulness 2025, 16, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederström, C.; Spicer, A. The Wellness Syndrome; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maniates, M.F. Individualization: Plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Glob. Environ. Politics 2001, 1, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior: A Theoretical Framework, Multilevel Review, and Future Research Agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonamallee, L. Expansive Leadership: Cultivating Mindfulness to Lead Self and Others in a Changing World—A 28-Day Program, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.J.; Malaktaris, A.L.; Casmar, P.; Baca, S.A.; Golshan, S.; Harrison, T.; Negi, L. Compassion meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: A randomized proof of concept study. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramstetter, L.; Rupprecht, S.; Mundaca, L.; Osika, W.; Stenfors, C.U.D.; Klackl, J.; Wamsler, C. Fostering collective climate action and leadership: Insights from a pilot experiment involving mindfulness and compassion. iScience 2023, 26, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J.; Dane, E. Mindfulness in organizations: A cross-level review. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Jstor: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 345–348. [Google Scholar]

- Clear, J. Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones; Avery: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- García-Campayo, J.; Demarzo, M.; Shonin, E.; Van Gordon, W. How Do Cultural Factors Influence Teaching and Practice of Mindfulness and Compassion in Latin Countries? Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, M.; Mika, J.P.; Leberman, S. Te Pā Auroa nā Te Awa Tupua: The new (but old) consciousness needed to implement Indigenous frameworks in non-Indigenous organisations. Altern. An. Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2022, 18, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, C. A river is born: New Zealand confers legal personhood on the Whanganui River to protect it and its native people. In Sustainability and the Rights of Nature in Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, J.; Croff, R.; Oken, B. Considerations for Research and Development of Culturally Relevant Mindfulness Interventions in American Minority Communities. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Roses, J. Barcelona’s Superblocks as Spaces for Research and Experimentation. J. Public. Space 2023, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioramonti, L.; Coscieme, L.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I.; Trebeck, K.; Wallis, S.; Roberts, D.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Wilkinson, R.; et al. Wellbeing economy: An effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecol. Econ. 2022, 192, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, H.E.; Alabanese, A.; Sun, S.; Saadeh, F.; Johnson, B.T.; Elwy, A.R.; Loucks, E.B. Mindfulness-Based stress reduction health insurance coverage: If, how, and when? An integrated knowledge translation (iKT) Delphi key informant analysis. Mindfulness 2024, 15, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poonamallee, L. Countering Climate Fear with Mindfulness: A Framework for Sustainable Behavioral Change. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146472

Poonamallee L. Countering Climate Fear with Mindfulness: A Framework for Sustainable Behavioral Change. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146472

Chicago/Turabian StylePoonamallee, Latha. 2025. "Countering Climate Fear with Mindfulness: A Framework for Sustainable Behavioral Change" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146472

APA StylePoonamallee, L. (2025). Countering Climate Fear with Mindfulness: A Framework for Sustainable Behavioral Change. Sustainability, 17(14), 6472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146472