Stakeholders’ Views on a Decadal Evolution of a Southwestern European Coastal Lagoon

Abstract

1. Introduction

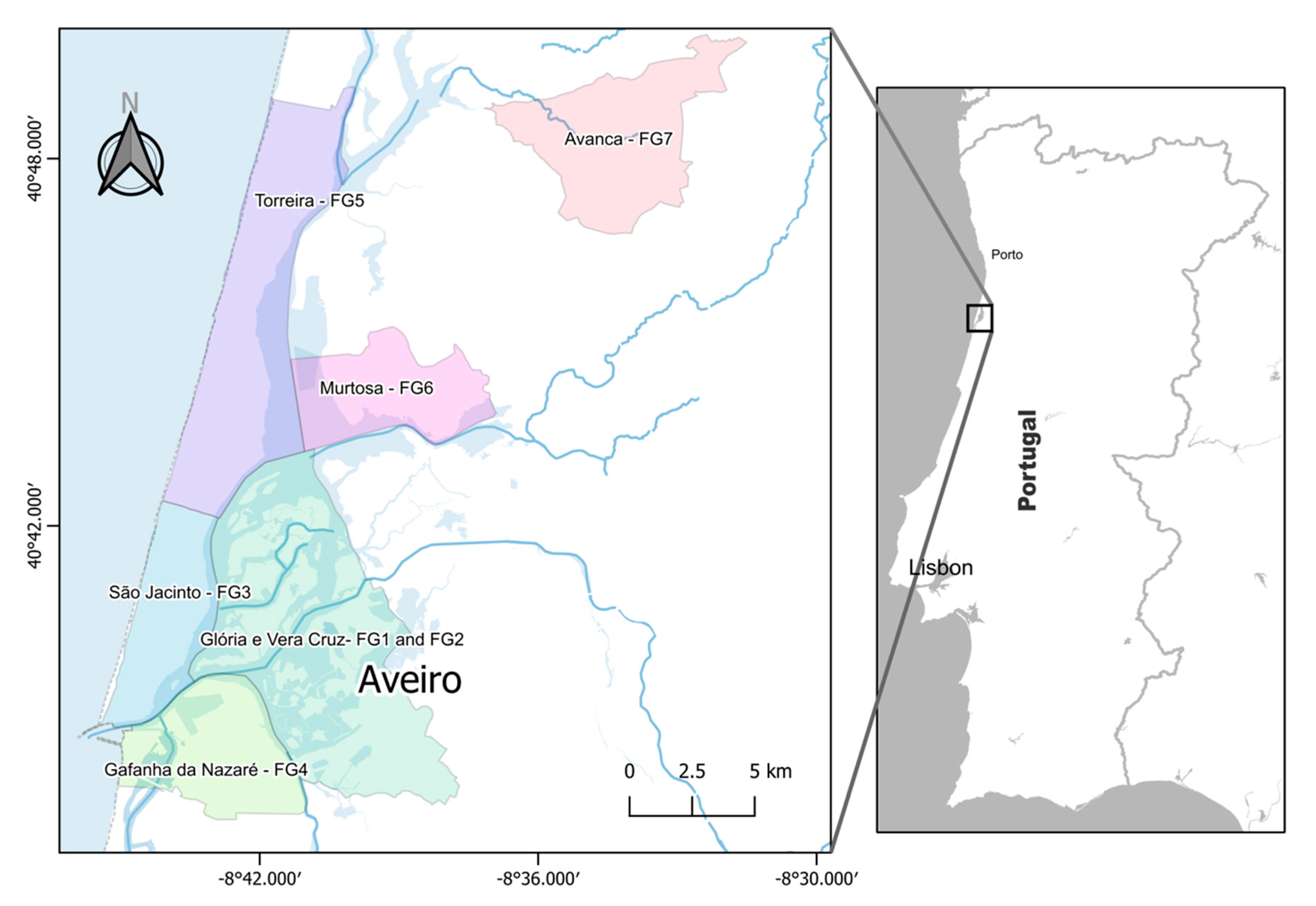

Ria De Aveiro Socio-Ecological System

2. Materials and Methods

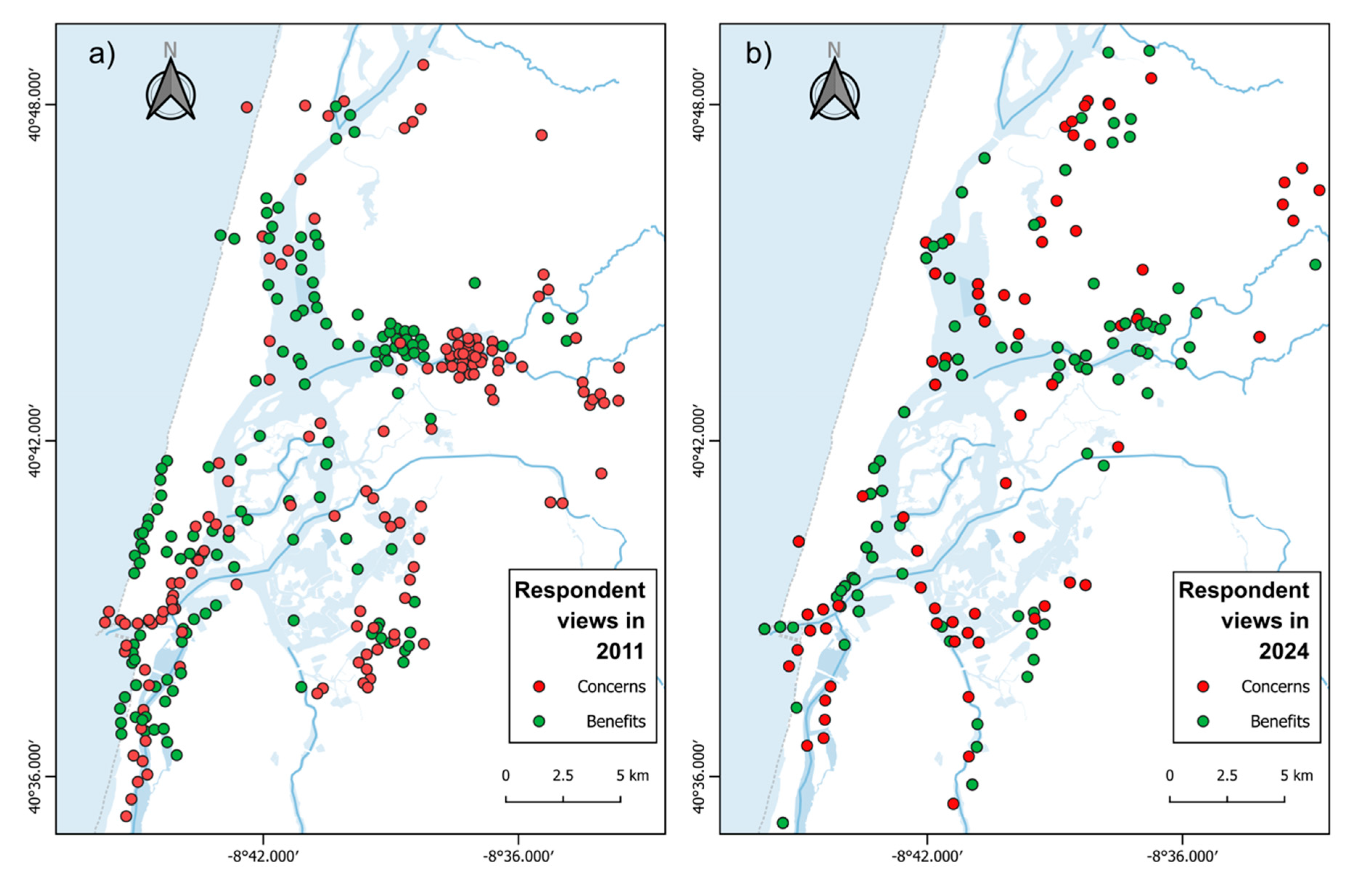

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Analytic Strategy

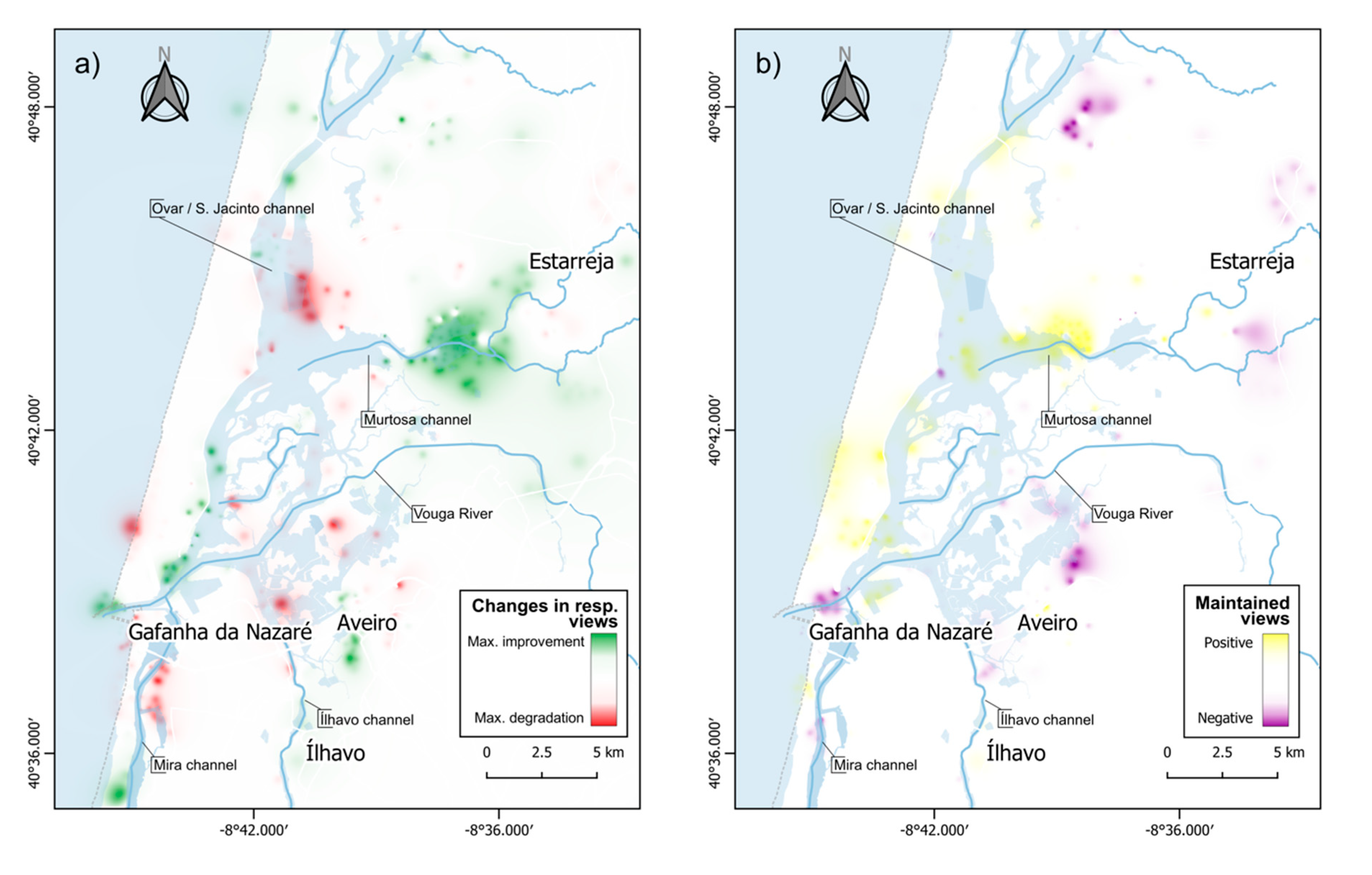

3. Results

- Improvement of environmental conditions

- Higher environmental consciousness and compliance

- Structural improvements

- Integrated management of Ria de Aveiro

- Hydrodynamic changes

- Biodiversity

- Tourism and water sports

4. Discussion

- What was perceived as positive and remains with a positive view

- What was perceived as positive and became a concern

- What was perceived as a concern and acquired a positive view

- What was perceived as a concern and remains a concern

- How do these compare to other coastal regions?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Backstrom, A.C.; Garrard, G.E.; Hobbs, R.J.; Bekessy, S.A. Grappling with the Social Dimensions of Novel Ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 16, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.P.; Alves, F.L. A Model to Integrate Ecosystem Services into Spatial Planning: Ria de Aveiro Coastal Lagoon Study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 195, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umantseva, A.; Dupret, K.; Lazoroska, D. Conducting Caring Collaborations in Societally Engaged Research: A Literature Review. Nord. J. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2025, 13, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science: Practice, Principles, and Challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, W.J.; Birnbaum, S.; Björkvik, E. The Quality of Compliance: Investigating Fishers’ Responses towards Regulation and Authorities. Fish Fish. 2017, 18, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanedel, R.; Gelcich, S.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Motivations for (Non-)Compliance with Conservation Rules by Small-scale Resource Users. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Nguyen, V.M.; Chapman, J.M.; Reid, A.J.; Landsman, S.J.; Young, N.; Hinch, S.G.; Schott, S.; Mandrak, N.E.; Semeniuk, C.A. Knowledge Co-Production: A Pathway to Effective Fisheries Management, Conservation, and Governance. Fisheries 2021, 46, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.; Williams, K.C.; Margeson, K.; Paczuski, S.; Hano, M.C.; Mulvaney, K. Advancing Translational Research in Environmental Science: The Role and Impact of Social Sciences. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 120, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S. Challenges and Opportunities of Area-Based Conservation in Reaching Biodiversity and Sustainability Goals. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.M.; Morrison, P.; Holzer, J.M.; Winkler, K.J.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Green, S.J.; Robinson, B.E.; Sherren, K.; Botzas-Coluni, J.; Palen, W. Facing the Challenges of Using Place-Based Social-Ecological Research to Support Ecosystem Service Governance at Multiple Scales. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Sherren, K.; Hanspach, J. Place, Case and Process: Applying Ecology to Sustainable Development. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2014, 15, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrasch, L.; Maier, M.; Kleyer, M.; Klenke, T. Collaborative Landscape Planning: Co-Design of Ecosystem-Based Land Management Scenarios. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.P.M.; Hinz, E.; Lang, D.J.; Tengö, M.; Wehrden, H.V.; Martín-López, B. Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Sustainability Transformations Research: A Literature Review. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder Participation for Environmental Management: A Literature Review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rölfer, L.; Celliers, L.; Fernandes, M.; Rivers, N.; Snow, B.; Abson, D.J. Assessing Collaboration, Knowledge Exchange, and Stakeholder Agency in Coastal Governance to Enhance Climate Resilience. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.; Schernewski, G.; Bielecka, M.; Loizides, M.I.; Loizidou, X.I. Methodologies to Support Coastal Management—A Stakeholder Preference and Planning Tool and Its Application. Mar. Policy 2018, 94, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordo, L.; Vasconcelos, P.; Piló, D.; Carvalho, A.N.; Pereira, F.; Gaspar, M.B. Recreational Harvesting of the Wedge Clam (Donax trunculus) in Southern Portugal: Characterization of the Activity Based on Harvesters’ Perception and Local Ecological Knowledge. Mar. Policy 2023, 155, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, W.L.; Zacardi, D.M.; Vieira, T.A. Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Fishermen: People Contributing towards Environmental Preservation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; De Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Brown, G.; Peterson, A.; Johnstone, R. Stakeholder Perspectives for Coastal Ecosystem Services and Influences on Value Integration in Policy. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 126, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.M.; Soares, P.M.M.; Lima, D.C.A.; Miranda, P.M.A. Mean and Extreme Temperatures in a Warming Climate: EURO CORDEX and WRF Regional Climate High-Resolution Projections for Portugal. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D. High-Resolution Surface Temperature Changes for Portugal under CMIP6 Future Climate Scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change Performance Index. Portugal. 2025. Available online: https://ccpi.org/country/prt/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Genua-Olmedo, A.; Verutes, G.M.; Teixeira, H.; Sousa, A.I.; Lillebø, A.I. A Spatial Explicit Vulnerability Assessment for a Coastal Socio-Ecological Natura 2000 Site. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1086135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. Social Capital and the Collective Management of Resources. Science 2003, 302, 1912–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental Governance: Participatory, Multi-level—And Effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.P.; Lillebø, A.I.; Gooch, G.D.; Soares, J.A.; Alves, F.L. Incorporation of Local Knowledge in the Identification of Ria de Aveiro Lagoon Ecosystem Services (Portugal). J. Coast. Res. 2013, 65, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; [Nachdr.]; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.E.; Lillebø, A.I.; Pato, P.; Válega, M.; Coelho, J.P.; Lopes, C.B.; Rodrigues, S.; Cachada, A.; Otero, M.; Pardal, M.A.; et al. Mercury Pollution in Ria de Aveiro (Portugal): A Review of the System Assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 155, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Coelho, J.P.; Cardoso, P.G.; Pereira, M.E.; Duarte, A.C.; Pardal, M.A. The Macrobenthic Community along a Mercury Contamination in a Temperate Estuarine System (Ria de Aveiro, Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 405, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.L.; Marques, B.; Dias, J.M.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Lillebø, A.I. Challenges for the WFD Second Management Cycle after the Implementation of a Regional Multi-Municipality Sanitation System in a Coastal Lagoon (Ria de Aveiro, Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltranaitė, E.; Inácio, M.; Valença Pinto, L.; Bogdziewicz, K.; Rocha, J.; Gomes, E.; Pereira, P. Tourism Impacts on Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.F.; Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Thomsen, D.C.; Celliers, L.; Le Tissier, M. Impacts of Tourism on Coastal Areas. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futur. 2023, 1, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism, Social Media Engagement with Issue; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2021/05/PS_2021.05.26_climate-and-generations_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Sousa, S.; Correia, E.; Leite, J.; Viseu, C. Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes and Behavior of Higher Education Students: A Case Study in Portugal. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2021, 30, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara Municipal de Aveiro. Turismo: Aveiro Bate Novo Recorde Em 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.cm-aveiro.pt/municipio/comunicacao/noticias/noticia/turismo-aveiro-bate-novo-recorde-em-2023 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ferreira Da Silva, M.; Vegas Macias, J.; Taylor, S.; Ferguson, L.; Sousa, L.P.; Lamers, M.; Flannery, W.; Martins, F.; Costa, C.; Pita, C. Tourism and Coastal & Maritime Cultural Heritage: A Dual Relation. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2022, 20, 806–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleiro, D.F.; Carneiro, M.J.; Breda, Z. Assessment of Residents’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards the Appropriation of Public Spaces by Tourists: The Case of Aveiro. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 922–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N.; Rossi, A.; Pavel, A.B. The Coastal Tourism Industry in the Mediterranean: A Critical Review of the Socio-Economic and Environmental Pressures & Impacts. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto-Lei n°. 73/2020, de 23 de Setembro. Diário Da República n.o 186/2020, Série I de 2020-09-23, 2-25. 2020. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/73-2020-143527213 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Silveira, F.; Lopes, C.L.; Pinheiro, J.P.; Pereira, H.; Dias, J.M. Coastal Floods Induced by Mean Sea Level Rise—Ecological and Socioeconomic Impacts on a Mesotidal Lagoon. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumares, D.; Fidelis, T. Natura 2000 Within Discursive Space: The Case of the Ria de Aveiro. Environ. Policy Gov. 2015, 25, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidélis, T.; Teles, F.; Roebeling, P.; Riazi, F. Governance for Sustainability of Estuarine Areas—Assessing Alternative Models Using the Case of Ria de Aveiro, Portugal. Water 2019, 11, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Região de Aveiro. Comunidade Intermunicipal Da Região de Aveiro. 2025. Available online: https://www.regiaodeaveiro.pt (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Fidélis, T.; Carvalho, T. Estuary Planning and Management: The Case of Vouga Estuary (Ria de Aveiro), Portugal. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 1173–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakou, E.G.; Kermagoret, C.; Liquete, C.; Ruiz-Frau, A.; Burkhard, K.; Lillebø, A.I.; Van Oudenhoven, A.P.E.; Ballé-Béganton, J.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Nieminen, E.; et al. Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services on the Science–Policy–Practice Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities from 11 European Case Studies. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillebø, A.I. Coastal Lagoons in Europe: Integrated Water Resource Strategies; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2015; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillebø, A.I.; Somma, F.; Norén, K.; Gonçalves, J.; Alves, M.F.; Ballarini, E.; Bentes, L.; Bielecka, M.; Chubarenko, B.V.; Heise, S.; et al. Assessment of Marine Ecosystem Services Indicators: Experiences and Lessons Learned from 14 European Case Studies. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2016, 12, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecka, M.; Różyński, G. Management Conflicts in the Vistula Lagoon Area. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 101, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Picado, A.; Vaz, N.; Coelho, C.; Portela, L.; Dias, J.M. Climate Change Effects on Suspended Sediment Dynamics in a Coastal Lagoon: Ria de Aveiro (Portugal). J. Coast. Res. 2018, 85, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Filho, J.L.; Macêdo, R.L.; Sarmento, H.; Pimenta, V.R.A.; Alonso, C.; Teixeira, C.R.; Pagliosa, P.R.; Netto, S.A.; Santos, N.C.L.; Daura-Jorge, F.G.; et al. From Ecological Functions to Ecosystem Services: Linking Coastal Lagoons Biodiversity with Human Well-Being. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2611–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotze, H.K.; Lenihan, H.S.; Bourque, B.J.; Bradbury, R.H.; Cooke, R.G.; Kay, M.C.; Kidwell, S.M.; Kirby, M.X.; Peterson, C.H.; Jackson, J.B.C. Depletion, Degradation, and Recovery Potential of Estuaries and Coastal Seas. Science 2006, 312, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, T.; West, E.; Robbins, T.; Plenty, S.; Sheehan, E. Large-Scale Historic Habitat Loss in Estuaries and Its Implications for Commercial and Recreational Fin Fisheries. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 79, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feunteun, E. Management and Restoration of European Eel Population (Anguilla anguilla): An Impossible Bargain. Ecol. Eng. 2002, 18, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ortegón, E.; Moreno-Andrés, J. Anthropogenic Modifications to Estuaries Facilitate the Invasion of Non-Native Species. Processes 2021, 9, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L.; Grosholz, E.D. The Invasive Species Challenge in Estuarine and Coastal Environments: Marrying Management and Science. Estuaries Coasts 2008, 31, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, H.O.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Schiavetti, A.; Magalhães, L. Checking the Changes over Time and the Impacts of COVID-19 on Cockle (Cerastoderma edule) Small-Scale Fisheries in Ria de Aveiro Coastal Lagoon, Portugal. Mar. Policy 2022, 135, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, A.E.; Frangoudes, K. Coastal and Maritime Cultural Heritage: From the European Union to East Asia and Latin America. Marit. Stud. 2024, 23, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Romero, M.J.; Chan, K.M.A.; McDaniels, T.; Dalmer, D.M. Structuring Decision-Making for Ecosystem-Based Management. Mar. Policy 2011, 35, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Bathing Water Quality. 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/bathing-water#:~:text=Bathing%20water%20quality%20at%20beaches,and%20actions%20by%20Member%20States (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Han, S.; Zhang, C.; Shan, B. Evidence of Improvements in the Water Quality of Coastal Areas around China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 832, 155147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Trentlage, J.; Burkhard, B. Matrix-Based Assessment of Spatial Correlations between Marine Uses and Ecosystem Service Supply in German Marine Areas. Landsc. Online 2023, 98, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, T.P.; Leonel, J.; Imperador, A.M. A Systemic Environmental Impact Assessment on Tourism in Island and Coastal Ecosystems. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Wei, J.; Zhu, J. The Effects of Improving Coastal Park Attributes on the Recreation Demand—A Case Study in Dalian China. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egberts, L. Heritage in European Coastal Landscapes—Four Reasons for Inter-Regional Knowledge Exchange. In Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage; Hein, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, T.P.; Ziveri, P.; Varela, B.; Colonese, A.C. Local Knowledge and Official Landing Data Point to Decades of Fishery Stock Decline in West Africa. Mar. Policy 2025, 171, 106447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, P.; Arias-Schreiber, M.; Svels, K. Societal Transformations and Governance Challenges of Coastal Small-Scale Fisheries in the Northern Baltic Sea. In Ocean Governance; Partelow, S., Hadjimichael, M., Hornidge, A.-K., Eds.; MARE Publication Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 25, pp. 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.S.; Côrtes, L.H.D.O.; Zappes, C.A. Critical Points Concerning Artisanal Fishing: An Analysis from the Perspective of Artisanal Fishers in Southeastern Brazil. Soc. Nat. 2024, 36, e71106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Positive Changes | Improvement of environmental conditions |

| Higher environmental consciousness and compliance | |

| Structural improvements | |

| Changes Worthy of Concern | Integrated management of Ria de Aveiro |

| Hydrodynamic changes | |

| Biodiversity | |

| Tourism and water sports |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinho, M.; Crespo, D.; Laranjeiro, D.; Lillebø, A.I. Stakeholders’ Views on a Decadal Evolution of a Southwestern European Coastal Lagoon. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146321

Pinho M, Crespo D, Laranjeiro D, Lillebø AI. Stakeholders’ Views on a Decadal Evolution of a Southwestern European Coastal Lagoon. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146321

Chicago/Turabian StylePinho, Mariana, Daniel Crespo, Dionísia Laranjeiro, and Ana I. Lillebø. 2025. "Stakeholders’ Views on a Decadal Evolution of a Southwestern European Coastal Lagoon" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146321

APA StylePinho, M., Crespo, D., Laranjeiro, D., & Lillebø, A. I. (2025). Stakeholders’ Views on a Decadal Evolution of a Southwestern European Coastal Lagoon. Sustainability, 17(14), 6321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146321