Self-Assessment Tool in Soft Skills Learning During Clinical Placements in Physiotherapy Degree Programs: A Pilot Validation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

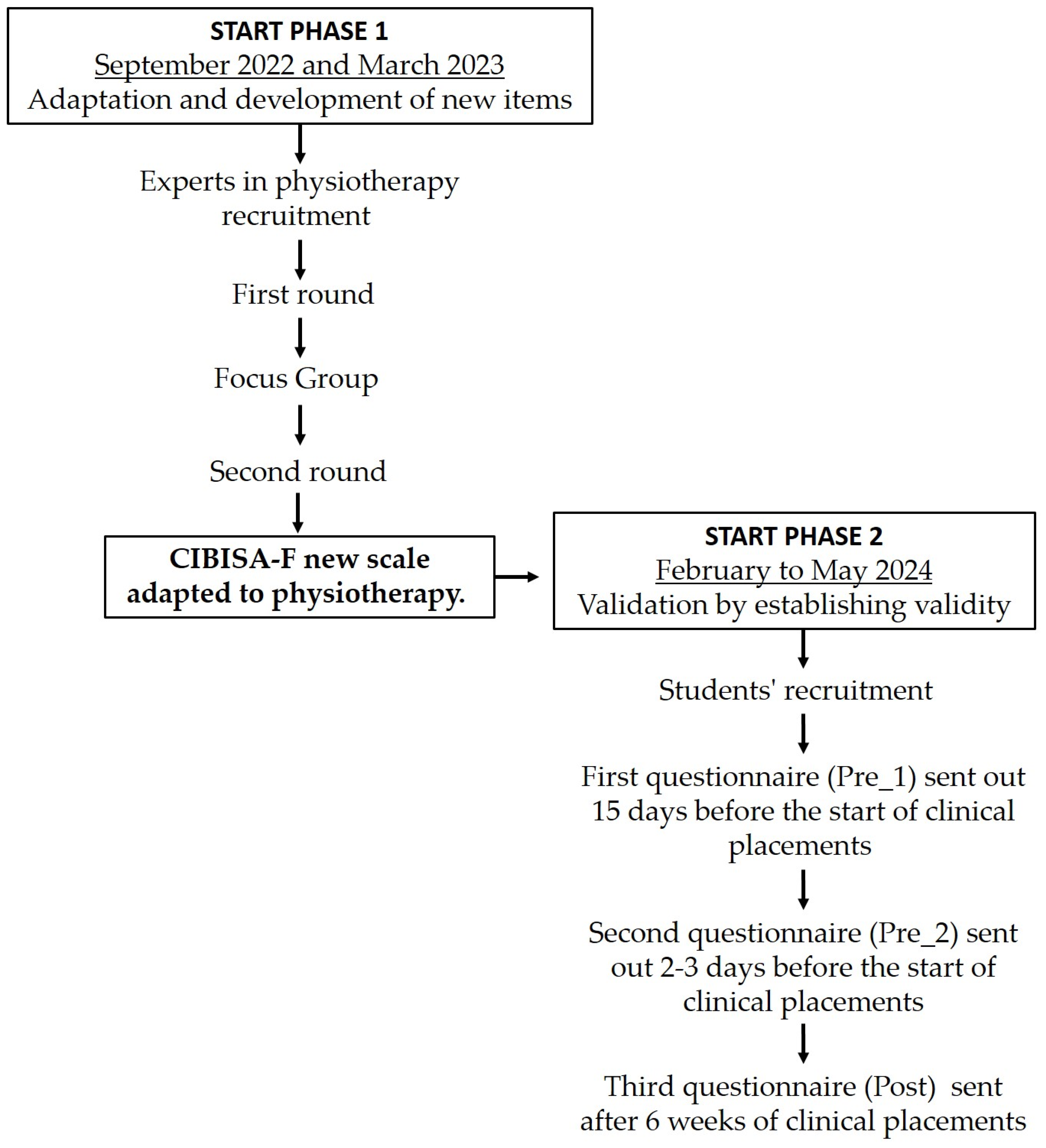

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Phase 1. Adaptation and Development of New Items

- Participants and data collection

2.2.2. Phase 2. Validation by Establishing Validity

- Sample and participants

- Psychometric Assessment

- CIBISA-F Scale properties

- The Goldstein Social Skills Assessment Scale

- The Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (EHC-PS)

- Data collection

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1. Adaptation and Development of New Items

3.1.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.1.2. Adaptation and Development of New Items

3.2. Phase 2. Validation by Establishing Validity

3.2.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2.2. Reliability

- Internal consistency

- Reproducibility

3.2.3. Construct Validity

3.2.4. Sensitivity to Change

4. Discussion

- Internal consistency

- Reproducibility

- Construct Validity

- Sensitivity to change

- Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIBISA | Invisible Care, Well-being, Security, and Autonomy nursing Scale |

| CIBISA-F | Invisible Care, Well-being, Security, and Autonomy Scale adapted to Physiotherapy |

| RD | Royal Degree |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| EHC-PS | Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale |

| Pre_1 | 15 days before clinical placements |

| Pre_2 | 2–3 days before clinical placements |

| Post | After clinical placements |

| D1-CI | Domain 1—Informative communication |

| D2-E | Domain 2—Empathy |

| D3-R | Domain 3—Respect and social skills |

| D4-A | Domain 4—Assertiveness |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| NSNS | Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scale |

References

- Martin Urrialde, J.A. Fisioterapia y Humanización: No Es Una Moda Sino Una Necesidad. Fisioterapia 2021, 43, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.; Rossettini, G. Enhance Placebo, Avoid Nocebo: How Contextual Factors Affect Physiotherapy Outcomes. Man. Ther. 2016, 24, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá, M.J.; Serpa, S. Higher Education as a Promoter of Soft Skills in a Sustainable Society 5.0. J. Curric. Teach. 2022, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés Muro, M.P.; Ayala Calvo, J.C.; Manzano García, G. Burnout in Nursing: A Vision of Gender and “Invisible” Unrecorded Care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 2148–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Fernández, R. La Humanización de (En) La Atención Primaria. Rev. Clín. Med. Fam. 2017, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tafese, M.B.; Kopp, E. Education for Sustainable Development: Analyzing Research Trends in Higher Education for Sustainable Development Goals through Bibliometric Analysis. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Fröberg, A. Towards a More Sustainable Future: Simple Recommendations to Integrate Planetary Health into Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e868–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Xumet, J.-E.; García-Hernández, A.-M.; Fernández-González, J.-P.; Marrero-González, C.-M. Vocation of Human Care and Soft Skills in Nursing and Physiotherapy Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velin, L.; Svensson, P.; Alfvén, T.; Agardh, A. What Is the Role of Global Health and Sustainable Development in Swedish Medical Education? A Qualitative Study of Key Stakeholders’ Perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, J.; Viñas, J.; Ballesta, J.; Román, A.G.; Rodríguez, F.; Rosselló, G. Libro Blanco: Título de Grado En Fisioterapia; Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de La Calidad y Acreditación (ANECA): Sevilla, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.T.; Bueno, C.R. Evaluación De Competencias Profesionales En Educación Superior: Retos E Implicaciones. Educ. XX1 2016, 19, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shan, J.; Zeng, L. Exploration and Practice of Humanistic Education for Medical Students Based on Volunteerism. Med. Educ. Online 2023, 28, 2182691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutac, J.; Osipov, R.; Childress, A. Innovation Through Tradition: Rediscovering the “Humanist” in the Medical Humanities. J. Med. Humanit. 2016, 37, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, G.; Collins, J.; Bedi, G.; Bonnamy, J.; Barbour, L.; Ilangakoon, C.; Wotherspoon, R.; Simmons, M.; Kim, M.; Schwerdtle, P.N. “I Teach It Because It Is the Biggest Threat to Health”: Integrating Sustainable Healthcare into Health Professions Education. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Physiotherapy. Physiotherapist Education Framework; World Physiotherapy: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Magni, E.; Teixeira-da-Costa, E.-I.M.; Oliveira, I.D.J.; Cáceres-Matos, R.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Exploring Physiotherapy Students’ Competencies in Clinical Setting Around the World: A Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Real Decreto 592/2014, de 11 de Julio, Por El Que Se Regulan Las Prácticas Académicas Externas de Los Estudiantes Universitarios; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Volume BOE-A-2014-8138, pp. 60502–60511. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2014/07/11/592 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Martiáñez Ramírez, N.L.; Rubio Alonso, M. Propuesta de Memoria del Estudiante de las Prácticas Clínicas Externas en el Grado en Fisioterapia Según Real Decreto 592/2014; Universidad Europea de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Ferrer, C.; Lucha-López, A.; Gasch-Gallén, A.; Urcola-Pardo, F.; Anguas Gracia, A.; Fernández-Rodrigo, M.T. Escala CIBISA y Eventos Notables: Instrumentos de Autoevaluación Para el Aprendizaje de Cuidados; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Urcola-Pardo, F.; Ruiz de Viñaspre, R.; Orkaizagirre-Gomara, A.; Jiménez-Navascués, L.; Anguas-Gracia, A.; Germán-Bes, C. La Escala CIBISA: Herramienta Para La Autoevaluación Del Aprendizaje Práctico de Estudiantes de Enfermería. Index Enferm. 2017, 26, 226–230. [Google Scholar]

- Varela-Ruiz, M.; Díaz-Bravo, L.; García-Durán, R. Descripción y usos del método Delphi en investigaciones del área de la salud. Investig. Educ. Méd. 2012, 1, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- García-García, J.A.; Reding-Bernal, A.; López-Alvarenga, J.C. Cálculo del tamaño de la muestra en investigación en educación médica. Investig. Educ. Méd. 2013, 2, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; van-der Hofstadt Román, C.J.; Rodríguez-Marín, J. Creación de La Escala Sobre Habilidades de Comunicación En Profesionales de La Salud, EHC-PS. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 49–59. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-97282016000100006 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Juliá-Sanchis, R.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Leal-Costa, C.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Escribano, S. Psychometric Properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale in University Students of Health Sciences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escala de Evaluación de Habilidades Sociales. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/latam/document/pontificia-universidad-catolica-madre-y-maestra/psicometria/escala-de-evaluacion-de-habilidadessocia/42433157 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo-Arias, A. Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2005, 34, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

- García de Yébenes Prous, M.J.; Rodríguez Salvanés, F.; Carmona Ortells, L. Validación de cuestionarios. Reumatol. Clín. Engl. Ed. 2009, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, R.M. Book Review: Psychometric Theory (3rd Ed.) by Jum Nunnally and Ira Bernstein New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994, xxiv + 752 pp. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 19, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pérez, J.A.; Pérez Martin, P.S. Coeficiente de correlación intraclase. Med. Fam. Semer. 2023, 49, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, N.; Ikiugu, M.N.; Hackett, F.; Sheffield, P.E.; Palipane, N.; Groome, J. Education for Sustainable Health Care: From Learning to Professional Practice. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán González-Serna, J.M.; Ferreras-Mencia, S.; Arribas-Marín, J.M. Development and Validation of the Hospitality Axiological Scale for Humanization of Nursing Care. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2017, 25, e2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Herera-Peco, I.; Molero Jurado, M.d.M.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. The Development and Validation of the Healthcare Professional Humanization Scale (HUMAS) for Nursing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Costa, C.; Tirado-González, S.; Rodríguez-Marín, J.; vander-Hofstadt-Román, C.J. Psychometric Properties of the Health Professionals Communication Skills Scale (HP-CSS). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huércanos-Esparza, I.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Orkaizagirre-Gómara, A.; Ramón-Arbués, E.; Germán-Bes, C.; Jiménez-Navascués, L. Measuring Invisible Nursing Interventions: Development and Validation of Perception of Invisible Nursing Care-Hospitalisation Questionnaire (PINC-H) in Cancer Patients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 50, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigacion en Enfermeria Imagen y Desarrollo. Available online: https://www.index-f.com/para/n9/pi009.php (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Stratford, P.W.; Riddle, D.L. Assessing Sensitivity to Change: Choosing the Appropriate Change Coefficient. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2005, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Yébenes Prous, M.J.G.; Rodríguez Salvanés, F.; Carmona Ortells, L. Sensibilidad al Cambio de Las Medidas de Desenlace. Reumatol. Clín. 2008, 4, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Correlation with Goldstein Scale (p-Value) | Correlation with EHC-PS (p-Value) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-CI | D2-E | D3-R | D4-A | |||

| Pre_1 | CIBISA-F | 0.370 (0.069) | 0.553 (0.004) | 0.729 (<0.001) | 0.449 (0.025) | 0.684 (<0.001) |

| Pre_2 | CIBISA-F | 0.714 (<0.001) | 0.614 (0.001) | 0.680 (<0.001) | 0.519 (0.008) | 0.615 (0.001) |

| Post | CIBISA-F | 0.688 (<0.001) | 0.608 (0.001) | 0.653 (<0.001) | 0.446 (0.025) | 0.232 (0.265) |

| Coefficient of Determination with Goldstein Scale (R2) | Coefficient of Determination with EHC-PS (R 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-CI | D2-E | D3-R | D4-A | |||

| Pre_1 | CIBISA-F | 0.137 | 0.306 | 0.532 | 0.201 | 0.46 |

| Pre_2 | CIBISA-F | 0.509 | 0.377 | 0.462 | 0.269 | 0.379 |

| Post | CIBISA-F | 0.473 | 0.369 | 0.426 | 0.199 | 0.054 |

| Comparison | Pre_1 Mean (SD) | Pre_2 Mean (SD) | p-Value * | Difference in Means (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIBISA-F | 102.24 (10.10) | 103.52 (7.68) | 0.555 | −1.28 (−5.68–3.12) |

| Comparison | Pre_1 Mean (SD) | Post Mean (SD) | p-Value * | Difference in Means (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIBISA-F | 102.24 (10.10) | 108.40 (7.74) | 0.005 | −6.10 (−10.22–−2.09) |

| Goldstein Social Skills Assessment scale | 192.8 (14.88) | 212.92 (24.44) | <0.001 | −20.84 (−29.78–−11.89) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galán-Díaz, R.M.; Jiménez-Sánchez, C.; Lafuente-Ureta, R.; Brandín-de la Cruz, N.; Burgos-Bragado, J.M.; Alonso-Cortés Fradejas, B.; Villa-Del-Pino, I.; Gómez-Barrera, M. Self-Assessment Tool in Soft Skills Learning During Clinical Placements in Physiotherapy Degree Programs: A Pilot Validation Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146304

Galán-Díaz RM, Jiménez-Sánchez C, Lafuente-Ureta R, Brandín-de la Cruz N, Burgos-Bragado JM, Alonso-Cortés Fradejas B, Villa-Del-Pino I, Gómez-Barrera M. Self-Assessment Tool in Soft Skills Learning During Clinical Placements in Physiotherapy Degree Programs: A Pilot Validation Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146304

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalán-Díaz, Rita María, Carolina Jiménez-Sánchez, Raquel Lafuente-Ureta, Natalia Brandín-de la Cruz, Jose Manuel Burgos-Bragado, Beatriz Alonso-Cortés Fradejas, Inmaculada Villa-Del-Pino, and Manuel Gómez-Barrera. 2025. "Self-Assessment Tool in Soft Skills Learning During Clinical Placements in Physiotherapy Degree Programs: A Pilot Validation Study" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146304

APA StyleGalán-Díaz, R. M., Jiménez-Sánchez, C., Lafuente-Ureta, R., Brandín-de la Cruz, N., Burgos-Bragado, J. M., Alonso-Cortés Fradejas, B., Villa-Del-Pino, I., & Gómez-Barrera, M. (2025). Self-Assessment Tool in Soft Skills Learning During Clinical Placements in Physiotherapy Degree Programs: A Pilot Validation Study. Sustainability, 17(14), 6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146304